Abstract

Carbonated drinks have been reported to increase muscle activity during swallowing compared with water. Older adults who habitually consume carbonated drinks may use their swallowing-related muscles to a greater extent, thereby preserving their swallowing function. This study investigated the relationship between habitual carbonated drink intake, amount of carbonated drink consumed, and subjective difficulty in swallowing in community-dwelling older adults. We administered a questionnaire to determine subjective difficulty in swallowing, nutritional status, presence of sarcopenia, and habitual intake of carbonated drinks. Statistical analysis of the subjective difficulty in swallowing was performed using logistic regression analysis with the presence or absence of suspected dysphagia, using the Eating Assessment Tool-10 as the dependent variable. The results showed that older age (odds ratio [OR]: 1.077; p = 0.011), nutritional status (OR: 0.807; p = 0.040), systemic sarcopenia (OR: 1.753, p < 0.001), and habitual intake of carbonated drinks (OR: 0.455; p = 0.039) were associated with subjective difficulty in swallowing. In conclusion, the daily habits of community-dwelling older adults impact their swallowing function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In older adults, a decline in swallowing function is caused by anatomical1,2 and functional3,4 changes in the muscles of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and upper esophagus. Increased thresholds of sensory receptors5,6 and decreased nerve conduction velocity7 also occur.

Presbyphagia is an age-related decline in swallowing function in older adults8. It differs from dysphagia in that the latter returns to normal with proper nutritional management and exercise guidance. Sarcopenic dysphagia is a comorbidity of decreased overall muscle strength, muscle mass, and swallowing function and is related to systemic sarcopenia9. The prevalence of systemic sarcopenia in the Japanese population increases with age, affecting approximately 22% of men and women aged 75–79 years, as well as 32% of men and 48% of women aged 80 + years10. The estimated prevalence of dysphagia in Japanese community-dwelling older adults is 16–23%, increasing to 27% in those aged > 75 years. However, studies on dysphagia in this population are lacking and the exact prevalence of sarcopenic dysphagia remains unknown11. However, the exact prevalence of sarcopenic dysphagia remains unknown.

Sarcopenia is related to nutritional status, and both nutritional and exercise interventions have been used to prevent it12. Nutritional management and exercises to strengthen swallowing-related muscles are also important in preventing sarcopenia and dysphagia9. Takeuchi et al.13 reported higher electromyography activity in the masseter and suprahyoid muscles when swallowing carbonated water than when swallowing still water. Min et al.14 reported that as carbonate concentration increased, the onset times of the orbicularis oris, masseter, submental muscle complex, and infrahyoid muscle contractions during swallowing decreased significantly. In contrast, the mean submental electromyography activity amplitude increased significantly. Krival and Bates15 reported that linguopalatal swallowing pressure significantly increased with the combination of carbonated and zingiber drinks compared to carbonated water and still water.

Thus, increased muscle activity and lingual swallowing pressure have been reported during the swallowing of carbonated drinks. It is possible that residents who habitually consume carbonated drinks routinely engage in higher oral and pharyngeal muscle activity than those who do not. Although there is no unified view on the intensity and frequency of resistance training for swallowing-related muscles among older adults, habitual intake of carbonated drinks may have a similar ability to resistance training to prevent sarcopenic dysphagia. We hypothesized that sarcopenic dysphagia and subjective difficulty in swallowing are related because the diagnostic criteria for sarcopenic dysphagia include impaired swallowing function and tongue pressure. In this study, we examined the association between the habitual intake of carbonated drinks and subjective swallowing difficulty in community-dwelling older adults.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Of the 351 participants who received the questionnaires, 325 (48 men and 277 women, mean age 77.6 ± 6.9 years) were included in the analysis after excluding participants with incomplete questionnaire entries. Of the 325 participants, 172 (52%) habitually consumed carbonated drinks. Table 1 lists the characteristics of the participants who consumed carbonated drinks (consumers) and those who did not (non-consumers). Among the participants, 44 (13.5%) had the Eating Assessment Tool-10 (EAT-10) score above the cutoff and were classified as having subjective difficulty in swallowing. Based on the Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA-SF), 96 participants (29.5%) were classified as being “at risk of malnutrition” and 3 (1.0%) as “malnourished”. The consumers were significantly younger (p = 0.019) and had a higher proportion of male participants (p = 0.007) than the non-consumers. There was no difference in nutritional status according to the MNA-SF or in the degree of systemic sarcopenia according to the Strength, Assistance in walking, Rise from a chair, Climb stairs, and Falls (SARC-F) questionnaire, which was better than the cutoff value of the mean. Similarly, the percentages of consumers and non-consumers who exceeded the cutoff value did not differ. Based on the EAT-10, subjective difficulty in swallowing was lower in the consumer group (p = 0.006); however, the mean of consumer group and non-consumer group were below the cutoff value. The percentage of participants above the cutoff was higher among non-consumers (p = 0.007). Among consumers, the can intake was 2.1 ± 2.7, which means they consume 2.1 cans (2.1*350 mL) per week. Fifteen participants had a habitual intake of carbonated drinks in the past but no current consumption. These participants had an EAT-10 score of 0.

Comparison of participants with and without subjective difficulty swallowing

The characteristics of participants with and without subjective difficulty in swallowing are shown in Table 2. Participants with subjective difficulty in swallowing were significantly older (p < 0.001), had a lower mean MNA-SF score (p < 0.001), had a higher mean SARC-F score (p < 0.001), had fewer remaining teeth (p = 0.002), and had higher denture use (p = 0.031). Significantly fewer participants had subjective difficulty in swallowing (p = 0.007). Sex, number of carbonated drinks consumed, and type of carbonated drink did not differ significantly between consumers.

Factors associated with subjective difficulty in swallowing

First, we examined whether subjective difficulty in swallowing was independently associated with age, nutritional status, degree of systemic sarcopenia, and carbonated drinks intake. To examine the factors associated with subjective difficulty in swallowing, we used a model with the independent variables set as age, total MNA-SF score, total SARC-F score, and current habitual intake of carbonated drinks (Table 3). In this model, age (odds ratio [OR], 1.077; p = 0.011), MNA-SF (OR, 0.807; p = 0.040), SARC-F (OR, 1.753; p < 0.001), and carbonated drink intake (consumer) (OR, 0.455; p = 0.039) were significantly associated with subjective difficulty in swallowing according to the EAT-10.

Next, we examined whether subjective difficulty in swallowing was independently related to age, nutritional status, degree of systemic sarcopenia, and number of carbonated drinks consumed. To examine the factors associated with subjective difficulty in swallowing, we used a model with age, total MNA-SF score, total SARC-F score, and current cans of carbonated drink intake as independent variables (Table 4). In this model, age (OR, 1.078; p = 0.010), MNA-SF (OR, 0.798; p = 0.033), and SARC-F (OR, 1.723; p < 0.001) were significantly associated with subjective difficulty of swallowing according to the EAT-10, but not with the amount of carbonated drink intake (intake cans).

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the habitual consumption of carbonated drinks is associated with subjective difficulty in swallowing in community-dwelling older adults; however, this relationship does not depend on the amount of carbonated drinks consumed.

In our study, 52% of participants habitually consumed carbonated drinks. To our knowledge, no previous study has examined the proportion of older adults in Japan who prefer carbonated drinks. Sweetened carbonated drinks are popular among United States older adults16. In these study revealed that carbonated drinks are the most commonly consumed drinks in United States, which is also likely to be true in Japan. Thickened carbonated drinks are preferred over non-carbonated liquids by Japanese patients with dysphagia and have also been reported to improve swallowing behavior17,18.

Age, nutritional status, sarcopenia, and carbonated drink consumption were identified as factors associated with subjective difficulty in swallowing. The proportion of patients with dysphagia increases with age11, and sarcopenic dysphagia is an independent risk factor of dysphagia in older adults in older adults19. Furthermore, in community-dwelling older adults, grip strength is associated with tongue pressure and bite strength, whereas walking speed is associated with lip movement and swallowing ability20. Thus, sarcopenia and dysphagia are interrelated. Sarcopenic dysphagia occurs when older adults with presbyphagia are exposed to low nutrition and invasive procedures that increase sarcopenia21. Furthermore, dysphagia can lead to undernutrition in older adults because of reduced variation in the foods they can eat22. Thus, nutritional status and dysphagia are also related.

Regarding the association between carbonated drink intake and the subjective difficulty in swallowing, we initially hypothesized that it was associated with the activity of swallowing-related muscles during carbonated drinks intake. However, the current study analyzed participants who consumed carbonated drinks at least once per week. Furthermore, no association was observed between carbonated drink intake and subjective difficulty swallowing. Among the studies on strengthening swallowing-related muscles, there are no reports on the effect of strengthening muscles less than once a week. No studies have directly compared muscle activity during the swallowing of carbonated drinks with conventional swallow training. However, a comparison of studies of swallowing-related muscle activity during carbonated drinks intake13,14 with studies of muscle activity during head-raising training23 and chin tuck exercises24 showed that muscle activity during swallowing of a carbonated drink was markedly lower than that during head-raising training and chin tuck exercises. These facts make it difficult to conclude that consuming carbonated drinks directly affects the subjective difficulty in swallowing.

We also considered that older adults with impaired swallowing tended to avoid the intake of carbonated drinks because it has been reported that carbonated drinks are difficult to swallow owing to the oral irritation caused by carbonation13. However, all participants who habitually consumed carbonated drinks but did not currently consume them had an EAT-10 score of 0. Therefore, it was ruled out that participants who developed subjective difficulty in swallowing discontinued the intake of carbonated drinks. To clarify the association between carbonated drink intake and subjective swallowing difficulty, the characteristics of older adults who consume carbonated drinks may be confounding factors.

This study aimed to clarify the attributes of older adults who consume carbonated drinks. Although activity levels and social interactions were not examined, older adults who habitually consume carbonated drinks may be more active than those who do not. Carbonated drinks may be consumed while being alone or in with the company of neighbors. Community residents aged > 40 years who interacted with neighbors and participated in leisure activities more frequently had higher tongue pressure25, as did older adults with a broader range of living arrangements26. These results suggest that maintaining and increasing speech and physical activity through social interaction may prevent sarcopenic dysphagia.

Our results do not indicate that carbonated drinks directly affect the swallowing function because the frequency of carbonated drink consumption is so low that carbonated drinks do not help maintain swallowing function. Additionally, the sugar in carbonated drinks can worsen oral health and increase the number of oral pathogens27, and aspiration of oral pathogens along with saliva may increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia27. The intake of carbonated drinks also increases an individual’s risk of diabetes and metabolic syndrome28. Even the ingestion of artificially sweetened beverages can risk an individual’s health29. Our findings do not support a high intake of carbonated drinks. Future research should identify the characteristics of older adults who prefer carbonated drinks and determine their effects on swallowing function. This study provides preliminary findings on the effect of carbonated drinks consumption on swallowing function.

Conclusion

Previous studies have reported that carbonated30 and thickened carbonated drinks18 immediately change swallowing dynamics in older patients with and without dysphagia. However, no reports have examined the long-term changes in swallowing dynamics after drinking carbonated drinks. The current study hypothesized that habitual intake of carbonated drinks would decrease the prevalence of subjective difficulty in swallowing among community-dwelling older adults. Our study is the first to report that habitual carbonated drink intake is associated with subjective difficulty in swallowing. Older age, malnutrition, sarcopenia, and lack of habitual intake of carbonated drinks are associated with subjective difficulty in swallowing in community-dwelling older adults. However, because older adults who consumed carbonated drinks less frequently were included in this study, we cannot conclude whether muscle activity during carbonated drink intake impacts swallowing function. Difficulty in swallowing in community-dwelling older adults may be related to the amount of physical activity and social interactions in daily life, which may be confounding factors for older adults who consume carbonated drinks. Future studies should identify the characteristics of older adults who prefer to consume carbonated drinks.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement.

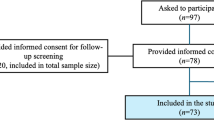

Participants

We targeted community-dwelling older adults attending care prevention activities at the Tokyo Metropolis and Okayama prefectures between 2021 and 2022. Among them, we included older adults who understood the study and did not have neurological diseases. The exclusion criteria comprised: older adults with cognitive impairment who had difficulty understanding the study content; those with neurological diseases such as stroke; and those who routinely use thickening agents or eat texture-modified diets. Because age, systemic sarcopenia, and nutritional status are associated with sarcopenic dysphagia in community-dwelling older adults31, we decided to use four factors as independent variables in the logistic regression analysis, along with carbonated drinks consumption. Peduzzi et al.32 demonstrated that bias, precision, model fit, and other problems with the analyses may occur when the size of any fewer categories of the dependent variable in a logistic regression analysis is less than ten times that of the explanatory variable. Therefore, we computed our sample size with the goal that the size of the smaller categories was at least 40 participants. The researchers asked participants to complete a questionnaire. We explained the purpose of the study, its content, how the results would be published, and the protection of participants’ privacy in writing. We also explained that we considered the participants’ questionnaire completion as informed consent for the study. The questionnaire was distributed to those individuals who indicated a willingness to cooperate (n = 351) and were collected on the same day. We conducted this study according to the Declaration of Helsinki and included in the questionnaire a document confirming that informed consent was obtained from all participants. We also obtained confirmation of informed consent and agreement to participate in the study from all participants. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kibi International University (approval No. 21-25).

Research instruments

The initial questionnaire included questions regarding age, sex, degree of dysphagia, nutritional status, degree of sarcopenia, number of remaining teeth, denture use, and the frequency of carbonated drink intake. We also investigated the presence of diabetes and liver disease, which may influence the consumption of carbonated drinks and beer. It is challenging to evaluate community-dwelling older adults using the standard diagnostic tools for dysphagia, such as swallowing videofluorography and fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES). Therefore, the EAT-1033, a subjective assessment of swallowing function, was used for evaluation. The EAT-10 has been shown to correlate with FEES results in patients admitted to rehabilitation hospitals34, and those with head and neck cancer35 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease36. Furthermore, the reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the EAT-10 have been previously reported37. The EAT-10 consists of 10 questions about swallowing problems, each of which is scored on a scale from 0 (“no problem”) to 4 (“severe problem”), and the total score is calculated. A total score of 3 points was considered “suspected dysphagia” . We defined subjective difficulty in swallowing as a total score of > 3. The MNA-SF38 was used to assess nutritional status. The MNA-SF consists of six items: weight loss, food deprivation, neuropsychological problems, mobility, psychological distress or acute disease, and body mass index. A total score of < 8 is considered “malnourished”, while a score of 8–11 indicates “at risk of malnutrition”. The reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the MNA-SF have been previously reported39. The Strength, Assistance in walking, Rise from a chair, Climb stairs, and Falls (SARC-F) questionnaire40 was used to assess sarcopenia severity. The SARC-F comprises five questions to be answered on a scale from 0 to 2––with 0 indicating “none,” 1 “a lot,” and 2 “unable”––for strength, assistance walking, rising from a chair, climbing stairs, and falls, with a total score of > 4 being “predictive of sarcopenia.” The reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the SARC-F have been previously reported41.

The survey on carbonated drink intake asked participants about the type of carbonated drink most frequently consumed, the average number of days consumed per week, and the amount consumed daily. Additionally, participants who had habitual intake in the past, even if they did not currently consume it, were asked to indicate the age at which they had habitual intake.

Statistical analysis

Habitual intake of carbonated drinks was defined as consumption at least once per week. We chose this criterion with consideration of our survey of participants, who reported habitually consuming carbonated drinks approximately once a week. If the frequency was less than that, we assumed the effect on swallowing function would be too small. The number of carbonated drinks consumed daily was not considered. There are no reports of alcohol content in drinks affecting swallowing function. Therefore, we counted and analyzed alcoholic and soft carbonated drinks together. The intake of carbonated drinks was calculated as an intake of at least 350 mL can per week based on the average number of days per week and the number of carbonated drinks consumed daily. For example, if they ingested 350 mL on 3 days per week, three cans would be recorded.

Student’s t test and the χ-squared test were performed to examine differences in the participants’ characteristics and respective total scores with versus without the current habitual intake of carbonated drinks. These tests were also used to examine differences in attribution due to subjective swallowing difficulty, with EAT-10 scores being ≥ 3 or < 3.

First, logistic regression analysis was performed with the presence or absence of subjective difficulty in swallowing on the EAT-10 as the dependent variable and age, total MNA-SF score, total SARC-F score, and current habitual intake of carbonated drinks as independent variables. Next, logistic regression analysis was performed with the presence or absence of subjective difficulty in swallowing on the EAT-10 as the dependent variable, age, total MNA-SF score, total SARC-F score, and number of cans of carbonated drink intake as independent variables. If the participant had previous habitual intake but was not currently consuming them, they were identified as “no habitual intake.”

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bardan, E. et al. Effect of ageing on the upper and lower oesophageal sphincters. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 1221–1225 (2000).

Malmgren, L. T., Fisher, P. J., Bookman, L. M. & Uno, T. Age-related changes in muscle fiber types in the human thyroarytenoid muscle: An immunohistochemical and stereological study using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 121, 441–451 (1999).

Takeda, N., Thomas, G. R. & Ludlow, C. L. Aging effects on motor units in the human thyroarytenoid muscle. Laryngoscope 110, 1018–1025 (2000).

Vaiman, M., Eviatar, E. & Segal, S. Surface electromyographic studies of swallowing in normal subjects: A review of 440 adults. Report 3. Qualitative data. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 131, 977–985 (2004).

Chauhan, J. & Hawrysh, Z. J. Suprathreshold sour taste intensity and pleasantness perception with age. Physiol. Behav. 43, 601–607 (1988).

Smith, C. H., Logemann, J. A., Burghardt, W. R., Zecker, S. G. & Rademaker, A. W. Oral and oropharyngeal perceptions of fluid viscosity across the age span. Dysphagia 21, 209–217 (2006).

LaFratta, C. W. & Canestrari, R. A comparison of sensory and motor nerve conduction velocities as related to age. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 47, 286–290 (1966).

Jahnke, V. Dysphagia in the elderly. HNO 39, 442–444 (1991).

Fujishima, I. et al. Sarcopenia and dysphagia: Position paper by four professional organizations. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 19, 91–97 (2019).

Kitamura, A. et al. Sarcopenia: Prevalence, associated factors, and the risk of mortality and disability in Japanese older adults. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 12, 30–38 (2021).

Eslick, G. D. & Talley, N. J. Dysphagia: Epidemiology, risk factors and impact on quality of life–a population-based study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 27, 971–979 (2008).

Beaudart, C. et al. Nutrition and physical activity in the prevention and treatment of sarcopenia: Systematic review. Osteoporos. Int. 28, 1817–1833 (2017).

Takeuchi, C. et al. Effects of carbonation and temperature on voluntary swallowing in healthy humans. Dysphagia 36, 384–392 (2021).

Min, H. S. et al. Effects of carbonated water concentration on swallowing function in healthy adults. Dysphagia 37, 1550–1559 (2022).

Krival, K. & Bates, C. Effects of club soda and ginger brew on linguapalatal pressures in healthy swallowing. Dysphagia 27, 228–239 (2012).

Wierenga, M. R., Crawford, C. R. & Running, C. A. Older US adults like sweetened colas, but not other chemesthetic beverages. J. Texture Stud. 51, 722–732 (2020).

Saiki, A. et al. Effects of thickened carbonated cola in older patients with dysphagia. Sci. Rep. 12, 22151 (2022).

Morishita, M., Okubo, M. & Sekine, T. Effects of carbonated thickened drinks on pharyngeal swallowing with a flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing in older patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia. Healthcare (Basel) 10, 1769 (2022).

Cha, S. et al. Sarcopenia is an independent risk factor for dysphagia in community-dwelling older adults. Dysphagia 34, 692–697 (2019).

Murotani, Y. et al. Oral functions are associated with muscle strength and physical performance in old-old Japanese. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 13199 (2021).

Wakabayashi, H. Presbyphagia and sarcopenic dysphagia: Association between aging, sarcopenia, and deglutition disorders. J. Frailty Aging 3, 97–103 (2014).

Wirth, R. et al. Oropharyngeal dysphagia in older persons—from pathophysiology to adequate intervention: A review and summary of an international expert meeting. Clin. Interv. Aging 11, 189–208 (2016).

Shaker, R. et al. Augmentation of deglutitive upper esophageal sphincter opening in the elderly by exercise. Am. J. Physiol. 272, G1518–G1522 (1997).

Yoon, W. L., Khoo, J. K. P. & Rickard Liow, S. J. Chin tuck against resistance (CTAR): new method for enhancing suprahyoid muscle activity using a Shaker-type exercise. Dysphagia 29, 243–248 (2014).

Nagayoshi, M. et al. Social networks, leisure activities and maximum tongue pressure: Cross-sectional associations in the Nagasaki Islands Study. BMJ Open 7, e014878 (2017).

Morishita, M. et al. Relationship between oral function and life-space mobility or social networks in community-dwelling older people: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 7, 552–560 (2021).

Müller, F. Oral hygiene reduces the mortality from aspiration pneumonia in frail elders. J. Dent. Res. 94, 14S-16S (2015).

An, H.-J., Kim, Y. & Seo, Y.-G. Relationship between coffee, tea, and carbonated beverages and cardiovascular risk factors. Nutrients 15, 934 (2023).

Shankar, P., Ahuja, S. & Sriram, K. Non-nutritive sweeteners: Review and update. Nutrition 29, 1293–1299 (2013).

Morishita, M., Mori, S., Yamagami, S. & Mizutani, M. Effect of carbonated beverages on pharyngeal swallowing in young individuals and elderly inpatients. Dysphagia 29, 213–222 (2014).

Azzolino, D., Damanti, S., Bertagnoli, L., Lucchi, T. & Cesari, M. Sarcopenia and swallowing disorders in older people. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 31, 799–805 (2019).

Peduzzi, P., Concato, J., Kemper, E., Holford, T. R. & Feinstein, A. R. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 49, 1373–1379 (1996).

Belafsky, P. C. et al. Validity and reliability of the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10). Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 117, 919–924 (2008).

Velasco, L. C. et al. Sensitivity and specificity of bedside screening tests for detection of aspiration in patients admitted to a public rehabilitation hospital. Dysphagia 36, 821–830 (2021).

Florie, M. et al. EAT-10 scores and fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing in head and neck cancer patients. Laryngoscope 131, E45–E51 (2021).

Regan, J., Lawson, S. & De Aguiar, V. The Eating Assessment Tool-10 predicts aspiration in adults with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Dysphagia 32, 714–720 (2017).

Wakabayashi, H. & Kayashita, J. Translation, reliability, and validity of the Japanese version of the 10-item Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) for the screening of dysphagia. J. JSPEN 29, 871–876 (2014).

Rubenstein, L. Z., Harker, J. O., Salvà, A., Guigoz, Y. & Vellas, B. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56, M366–M372 (2001).

Kuzuya, M. et al. Evaluation of mini-nutritional assessment for Japanese frail elderly. Nutrition 21, 498–503 (2005).

Malmstrom, T. K. & Morley, J. E. SARC-F: A simple questionnaire to rapidly diagnose sarcopenia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 14, 531–532 (2013).

Kurita, N., Wakita, T., Kamitani, T., Wada, O. & Mizuno, K. SARC-F Validation and SARC-F+EBM derivation in musculoskeletal disease: The SPSS-OK study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 23, 732–738 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our deepest gratitude to the public health nurses who managed the care prevention project, study volunteers, and study participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: M.M.; Methodology: M.M.; Data collection: M.M., Y.K., A.Y., and T.H.; Data analysis: M.M.; Writing—original draft preparation: M.M.; writing—review and editing: Y.K., A.Y., and T.H.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morishita, M., Kunieda, Y., Yokomizo, A. et al. Habitual intake of carbonated drinks is associated with subjective difficulty in swallowing in community-dwelling older adults: a survey-based cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 14, 19774 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70878-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70878-6