Abstract

The impact of premade beef patty (BBP) with red onion skin powder (OSP) at 0, 1, 2, and 3% levels on color, lipid, and protein oxidative stability, and infection degree of microorganisms during cold storage was investigated. The objective was to determine the effect of color by L*, a*, b*, and the content of MetMb. The inhibitory effect of OSP on the oxidation of lipid and protein was studied based on TBARS and the carbonyl content of protein in samples at different storage times. TVB-N content was used to characterize the degree of infection of microorganisms and their effect on meat quality. The results showed that the addition of OSP reduced the pH, L *, a*, and b * values of BBP, and improved the hardness, springiness, gumminess, and cohesiveness of BBP, but had no significant effect on the chewiness of BBP (p > 0.05). After 12 days of storage, the carbonyl group and TBARS content in the BBP supplemented with 3%OSP was significantly lower than that in the control group (p < 0.05). Furthermore, the addition of OSP significantly inhibited the TVB-N increase during beef patty storage. These results indicated that OSP has a good research prospect as a natural antioxidant or preservative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As consumers further understand the link between diet and health, the demand for healthy and safe foods gradually increases1,2. Beef is a widely consumed food, and beef products are viewed as an essential source of consumer needs and nutrition3. High moisture content, high oxygen partial pressure, and enzyme activity in fresh beef patties will promote fat oxidation, while high protein content is conducive to microbial growth during storage4. In addition, the storage time of beef patties is too long, which will lead to the surface color of meat browning, flavor deterioration, quality decline, and shorten shelf life, resulting in certain economic value losses5. To prevent beef product spoilage and prolong the shelf life, antioxidants or preservatives were usually used to suppress fat oxidation, protein oxidation, and microbial infection in beef6. Synthetic antioxidants such as 2,6-dibutylated hydroxyl toluene (BHT) and butylated hydroxyl anisole(BHA) are widely used. Studies have shown that such antioxidants have significant antioxidant effects, but overuse may cause health risks, such as cancer, allergy, infertility, and others7. These defects have led to consumer resistance to synthetic antioxidants, while attracting more attention from consumers and researchers for the natural, non-toxic, and healthy advantages of natural antioxidants8.

Therefore, many natural additives have been the research subject in recent years. In this sense, by-product extracts from food processing are potential sources of natural antioxidant and antimicrobial compounds that could prevent oxidative reactions on lipids, inhibit undesirable microbial growth, and, consequently, extend the shelf-life of meat and meat products9. Recently, many researchers have added plant materials rich in phenolic compounds such as olive oil waste10, Guarana seeds11, black rice extract12, mulberry leaf extract13, pomegranate peel extract14 and pericarp of Szechuan pepper15 from the food industries, have been used successfully in different meat models. In this regard, using by-products of vegetable processing, such as onion skins, has been reported previously16,17.

Onions are the second most widely cultivated vegetable globally, with China alone producing tens of thousands of tons of onion processing waste annually18. Onion skin accounts for about 60% of the total waste, which contains significantly higher dietary fiber, polyphenols, and other bioactive compounds, especially quercetin and its derivatives, mainly represented by glucoside19. Moreover, onion and its by-products have various biological in vitro and in vivo activities, such as antioxidant activity, antimicrobial properties, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties20. In recent years, onion skins have gained increasing attention as a functional food ingredient added to wheat noodles21, raw ground pork6, and chicken patties3 to improve health or extend the shelf life of products. However, research on the storage effect of onion skin powder on beef patty has rarely been reported.

Combined with the above views, different proportions of onion skin powder were added to the beef patty, and the meat quality pH, color, thiobarbituric acid reactant value (TBARS), volatile salt base nitrogen value (TVB-N), carbonyl content, and other indicators during cold storage were analyzed. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the effect of onion peel powder on beef patties with onion peel powder as a natural source of antioxidants on the color, fat, and protein oxidation, as well as the decay of beef patties during refrigeration.

Materials and methods

Materials

The fresh beef was purchased from the Qiqihar Longjiang Yuansheng Food Co., LTD. Purple onion skins were obtained from the Qiqihar farmer's market; 2-thiobarbituric acid (2-TBA), Coolaber Technology Co., LTD., Beijing; Guanidine hydrochloride (analytically pure), 2, 4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH), Sinopharm Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd. Ascorbic acid (AA, food grade), Hebei Wellkang Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Peptone, AGAR, yeast extract (biological reagent), Beijing Aoboxing Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The remaining reagents were of analytical grade.

Methods

Preparation of OSP

The onion skins were washed with distilled water to remove surface impurities. The washed onion skins were dried at 40 °C for 12 h (GZX-9146 MB air dry oven, Shanghai Boxun Industrial Co., LTD). The crushed onion skin powder was sieved through a 100-mesh screen to make beef patties.

Preparation of beef bread

Fresh beef was shipped to the laboratory in a crisper. Subsequently, the connective tissue was removed from the beef spine using a meat grinder (JR-32L meat grinder, Zhucheng Huagang Machinery Co., LTD) equipped with a 6 mm hole plate. The beef patties were prepared in accordance with the method reported by Zahid et al.22. The recipe contains the following ingredients: 1000 g of beef, 120 g of ice water, 1.5% (w/w) salt, and OSP in various proportions (0, 1.0%, 2.0%, and 3.0%, percentage of beef weight). Beef patties supplemented with 0.05% ascorbic acid (AA) were used as a positive control. The well-blended ground beef was formed into patties using a handheld patty mold that weighs (80 g), has a diameter of 10 cm, and a thickness of 1 cm. Beef patties were packaged in an oxygen-permeable polyethylene pouch and sealed, then stored at 4 °C. Subsequently, fresh beef patties kept at 4 °C were analyzed for samples at 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 days for pH, color values, texture features, TBARS value, carbonyl content, TVB-N, and total number of colonies.

pH values

The pH was determined according to the protocol described by Basiri et al.23. Accordingly, 10 g of meat samples was homogenized in 50 mL of distilled water using a mortar (n = 3). The pH was then determined with a digital pH meter (Five Easy Plus pH meter, Mettler-Toledo Instruments (Shanghai) Co., Ltd).

Metmyoglobin (MetMb) content

The MetMb content of beef patties was determined using the procedures reported by Cui et al.24. Accordingly, 3 g of sample was added to 30 mL of 0.04 mol/L phosphate buffer (pH 6.8, 4 °C), mixed thoroughly, and then refrigerated at 4 °C for 1 h. The samples were incubated and centrifuged for 10 min in a high-speed refrigerated centrifuge (8000 r/min, 4 °C) (Allegra 64R frozen centrifuge, Beckman, USA). Subsequently, the supernatant's absorbance (UV-5100 UV–Visible spectrophotometer, Shanghai Yuanyuan analysis instrument Co., Ltd) was measured at 525 nm, 572 nm, and 700 nm following filtration with a filter paper. The calculation formula of MetMb content was as follows Eq. (1):

Abs525 denotes the absorbance of the sample reaction solution at wavelength 525 nm, Abs572 denotes the absorbance of the sample reaction solution at wavelength 572 nm, and Abs700 denotes the absorbance of the sample reaction solution at wavelength 700 nm.

Carbonyl content

The carbonyl content was measured as reported by Vuorela et al.25. With some modification. 10 g of sample was triturated with pestle and mortar in 10 mL KCl (0.15 M, 4 °C). Two aliquots of 0.2 mL homogenate added 1 mL of 10% TCA (4 °C). Then, they were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min. One precipitation was added to 1 mL of 2 M HCl (4 °C) for protein quantification, and another was added to 0.2% DNPH (4 °C) for carbonyl quantification. After incubation at room temperature for 1 h, they were added to 1 mL of 10% TCA and centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting precipitate was washed three times with 1 mL ethanol/ethyl acetate (1:1) to remove excess DNPH. The remaining small particles were dissolved in 1.5 mL of 6 M guanidine hydrochloride solution and centrifuged for 5 min (6000 rpm). The concentration of carbonyl and protein was determined by spectrophotometry at 370 nm and 280 nm. The carbonyl content was expressed using bovine serum albumin as standard: nmol carbonyl/mg protein, Eq. (2).

where 21.0 mM–1 cm–1 is the molar extinction coefficient of carbonyls.

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) value

TBARS were measured using a modified version of the procedure reported by Zengin and Bayasal 26. About 10 g of samples were ground in a mortar with 25 mL of a 20% trichloroacetic acid solution (4 °C). Subsequently, the mortar was rinsed with 25 mL of distilled water at 4 °C, and then the contents were transferred to a 100 mL beaker. The mixture was then strained using a quantitative filter paper (Whatman Grade NO.44: aperture 3 μm). Subsequently, 3 mL of 5-mmol/L 2-TBA was added to 3 mL of filtrate in a centrifuge tube and immersed in a 95 °C water bath for 30 min. The reaction was then terminated using cold water. For the blank experiment, the sample filtrate was replaced by 3 mL of 10% trichloroacetic acid. Subsequently, the sample's absorbance at 532 nm was measured using a UV spectrophotometer. The TBARS value was calculated by comparing the standard curve of 1,1,3,4-tetraethoxypropane (TEP). The standard curve equation was as follows: y = 0.0818x + 0.0210, R2 = 0.9986. The TBARS values were expressed as mg MDA / kg (in meat samples) (MDA is malondialdehyde).

TVB-N

The TVB-N analysis was carried out in accordance with Basiri et al. 23. Correspondingly, 10 g of the sample was ground to ground meat, and 100 ml of distilled water was added. The ground sample was then soaked at room temperature for 30 min, filtered, and the filtrate was extracted and distilled utilizing a semi-trace fixed nitrogen distillation apparatus (Semi-trace fixed nitrogen distillation instrument, School of Food and Bioengineering, Qiqihar University.). The sample was monitored from the time when the first drop of condensate fell. The condensate was then added to a beaker containing 10 mL of 2% boric acid solution and 5–6 drops of an indicator mixture (0.2% methyl red solution and 0.1% methyl blue solution were mixed in equal proportions). The catheter was then removed after 5 min and immediately titrated with 0.01 mol/L HCl until a bluish-purple color was obtained. Concurrently, the reagent-blank experiment was performed. TVB-N values were expressed in mg of TVB-N per 100 g of beef, and the calculation formula was as follows Eq. (3):

where v1 denotes the volume of HCl standard solution consumed by sample solution, mL, v2 denotes the volume of HCl standard solution consumed by reagent blank, mL, M is the molar concentration of the hydrochloric acid standard solution (mol/L); m, sample mass, g.

Total plate count (TPC)

The TPC was determined using the plate pour technique23. First, 10 g of samples were homogenized in 90 mL of 0.85% sterile saline for 30 min. Subsequently, serial decimal diluents were prepared using sterile saline. Then, about 1 mL of the diluent was poured into the plate and the plate was covered. Subsequently, AGAR was counted in sterile plates that were then incubated for 48 h at 37 °C (Water isolation incubator, Tianjin Best Instrument Co., Ltd.). Following culture, the count of colonies was recorded and expressed as log10 CFU/g.

Color

The L* value (brightness), a* value (red/ green), and b* value (yellow/ blue) of the sample were measured using a chromometer (CR-10 Plus Colorimeter, Konica Minolta Optics Co., LTD). The color difference meter utilized a D65 viewing light source, an 8 mm measuring diameter, and a 10° Viewing Angle. Five different points were measured for each sample. The total color difference (ΔE*) was calculated according to the methodology of Bellucci et al.27 (Eq. 4):

where \({L}_{0}^{*}\), \({a}_{0}^{*}\), and \({b}_{0}^{*}\) denote the L* value (brightness), a* value (red/ green) and b* value (yellow/blue) at day 0; additionally,\({L}_{3-12}^{*}\), \({a}_{3-12}^{*}\), and \({b}_{3-12}^{*}\) denote the L*, a*, and b* of days 3–12.

Analysis of the texture properties

The study of texture characteristics of beef patties was based on the method reported by Bahmanyar et al.28 with minor modifications. Beef patties, sized 2 cm × 2 cm × 1 cm were placed on the carrier table of the food physical property analyzer (TMS-Pro Food Property Analyzer, Food Technology Corporation Company) in order to measure the sample's hardness (N), cohesiveness, springiness (mm), Gumminess (A2/A1, A1 is the total energy required for the first compression, A2 is the total energy required for the second compression), and chewiness (g × mm). The property analyzer used a 38.1 mm cylindrical plastic probe, with a probe rise height of 20 mm, drop speed of 2 mm/s, and a compression ratio of 50%.

Statistical analysis

All tests were repeated three times, and the results were expressed as “mean ± standard deviation”. Means with a standard error of means were exhibited from three replications to execute statistical data analysis. The SPSS programming, as edition 11.5, was utilized to analyze the data. The variance analysis (ANOVA) process was performed in this research. In addition, Duncan's multiple range tests were utilized to identify the substantial difference of means among the treatments. Accordingly, p < 0.05 indicated statistically significant differences. The data were plotted using Origin Pro 8.5.

Results and discussion

Effect of OSP on the oxidative stability of beef patties

MetMb content of beef patties

Fresh beef is rapidly exposed to the air, and the myoglobin in the beef combines with oxygen to form oxymyoglobin (bright red)29. When oxymyoglobin is touched with oxygen for a long time, the Fe2+ in the oxymyoglobin is gradually oxidized to form Fe3+, and at this time, the oxymyoglobin is transformed into metmyoglobin (reddish-brown), resulting in a decrease in the commodity value of beef and its products24. During the processing of beef patties, the myoglobin in the beef has long-term contact with a large amount of mixed oxygen and metal equipment, which accelerates the transformation of myoglobin and oxymyoglobin in the beef to metmyoglobin, resulting in the deterioration of the color of the beef patties8. Figure 1 shows the effect of different proportions of OSP on MetMb content during refrigeration of beef patties. At 0–3 days, MetMb content did not differ significantly among treatment groups (p > 0.05). On day 12, compared to the control, the MetMb content of beef patties treated with 1.0%, 2.0%, and 3.0% OSP decreased by 9.70%, 17.99%, and 26.46%, respectively. In addition, there was no statistically significant difference between the MetMb content of the 2.0% OSP group (31.96%) and the AA group (32.4%) (p > 0.05). These results indicate that OSP treatment can effectively delay the formation of MetMb in beef patties and that OSP at a concentration of 2.0% can achieve the antioxidant effect of the synthetic additive AA. In addition, the accumulation of MetMb and the discoloration of meat during cold storage are significantly influenced by the type of meat and the presence of lipid redox systems29. Red meat, such as beef, is rich in myoglobin, which oxidizes ferrous ions to trivalent iron ions in the presence of primary lipid oxidation products (hydroperoxides and reactive oxygen species) and contributes to the conversion of OxyMb to MetMb30. As an important source of quercetin and its derivatives, onion skin has high antioxidant and iron-reduction capacities, allowing it to delay the formation of MetMb in beef3. In this regard, Papuc et al.2 discovered that strong reducing agents like quercetin, kaempferol, and myricetin in the ethanol extract of hawthorn could convert MetMb to Oxymb in refrigerated pork mince. Similar results were also reported by Lee et al.29 who demonstrated that the addition of pickle extract to stored raw pork decreased its MetMb content.

Carbonyl content

The content of carbonyl in protein is an important index to judge the degree of protein oxidation in meat16. Protein carbonylation is mainly produced by the oxidation of protein amino acids with free radicals, hydroperoxides, and aldehydes produced by fat oxidation31. Protein carbonylation can cause the breakdown of peptide bonds and the decomposition of amino acid side chains, which leads to the oxidative degradation of some amino acid side chains (such as lysine, proline, arginine, and histidine residues), and reduces the quality of meat22. Figure 2 shows the effect of different proportions of OSP on the carbonyl content of beef patties during refrigeration. The addition of OSP reduces the generation of carbonyl and presents a dose-dependent effect. As storage time increased, carbonyl content in beef patties was significantly increased (p < 0.05). At the end of the storage, the carbonyl content of the control increased from 3.16 to 18.13 nmol/mg. The addition of 3.0% OSP significantly reduced the beef carbonyl content (14.63 nmol/mg), which was lower than 14.95 nmol/mg in the AA-treated group. This is consistent with the inhibitory effect of OSP on lipid oxidation in beef patty. Zhang et al.32 reported that the addition of clove extract substantially restrained carbonyl production in pork sausage and this antioxidant activity of clove extract for restraining the carbonyl production might be due to the presence of phenolic compounds. Chauhan et al.30 also suggested that Terminalia arjuna fruit extract significantly lowered the formation of protein carbonyls in raw pork in a control sample during storage.

Effect of OSP on Carbonyl content of beef patties during refrigerated storage. Different letters of a-d represent significant differences in different treatment groups at the same refrigeration time (p < 0.05); different letters of A–E represent significant differences in different refrigeration times at the same treatment group (p < 0.05).

TBARS value of beef patties

The TBARS values quantify aldehydes reactive with barbiturates, associated with the accumulation of secondary products, and are widely used as an indicator of fat oxidation33. Fat oxidation involves a series of interactions between unsaturated fatty acids and molecular oxygen that produce labile primary products that can be further decomposed into the secondary product MDA33. It is interesting to note that the antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds is related to the hydroxyl group attached to the aromatic ring17. Accordingly, hydroxyl groups stabilize free radicals by supplying hydrogen atoms and electrons, thereby preventing further degradation of lipids into more active oxidized forms, such as MDA29.

Figure 3 shows the effects of different additive treatments and storage times on the concentration of malondialdehyde (MDA) in beef. 3 days before storage, there was no significant difference in lipid oxidation values between treatment groups (p > 0.05). However, the TBARS value in the beef patties increased rapidly after 6 days of storage. Subsequently, on 12 days, the TBARS value of the control increased to 1.28 mg MDA kg−1, which was significantly greater than those of the OSP and AA groups (p > 0.05). When compared with the control, the TBARS value of beef patties treated with 3.0% OSP and AA decreased by 24.22% and 28.13%, respectively. This suggests that OSP was capable of inhibiting lipid oxidation and, with increasing doses, can achieve the same effect as AA. The application of OSP in cooked chicken patties has been reported to reduce TBARS3. This is usually attributed to the large amount of flavonoids present in onion skin, resulting in its potent antioxidant ability. Moreover, flavonoids have also been reported to interrupt the chain of oxidation of free radicals by contributing hydrogen from the hydroxyl group, thereby forming stable end products34. In addition, studies conducted by Jiao et al.33 show that phenolic substances extracted from kiwifruit that are added to beef as natural antioxidants effectively prevent lipid oxidation.

Effect of OSP on TBARS of beef patties during refrigerated storage. Different letters of a–c represent significant differences in different treatment groups at the same refrigeration time (p < 0.05); different letters of A–E represent significant differences in different refrigeration times at the same treatment group (p < 0.05).

OSP on the antibacterial activity of beef patties

pH of beef patties

During the storage process, the muscle glycogen in beef through anaerobic glycolysis produces a large amount of lactic acid, and ATP enzymatic phosphorylation could cause a decrease in meat pH32. However, with the extension of the storage period, due to the influence of its own enzymes and microorganisms, the protein in the beef could decompose into small molecule deamination substances and amine compounds, which will cause the gradual rise of the pH of the meat quality35. Moreover, the decreased pH caused by the accumulation of lactic acid in beef was able to inhibit microbial growth. In this regard, pH comprises one of the most critical factors influencing food preservation and safety19.

The effect of OSP treatment on beef pH during refrigeration is shown in Table 1. On day 0, the pH of the OSP group (5.38–5.48) was significantly lower than that of the blank control group (5.57). Bedrníček et al. also reported the same result, implying that the pH reduction of the fish sausage was due to the acidic nature of OSP. On day 12, the pH of beef patties treated with 3.0% OSP and AA decreased significantly (p < 0.05) by 0.18 and 0.05, respectively, when compared to the blank control group (pH = 5.81). This may be because the polyphenols in onion skin inhibit the decomposition of protein in meat and reduce the formation of alkaline substances (Hajrawati et al. 2019). In addition, onion skins contain a high concentration of pectin, mainly composed of galacturonic acid, resulting in their acidity19. Moreover, Kurt et al.3 also discovered that the pH of raw and cooked chicken patties decreased with increasing OSP content. In addition, Aksu et al.36 found that the pH of grounded beef decreased after frozen, dried red cabbage water extract to beef patties, thereby delaying the proteolytic changes in ground beef during storage.

TVB-N content of beef patties

Endogenous enzymes or spoilage bacteria can degrade proteins and other nitrogen-containing substances in meat into volatile bases such as ammonia, trimethylamine, and dimethyl amine to form volatile salt base nitrogen (TVB-N), so TVB-N is one of the essential indicators to evaluate the quality of fresh meat35. There was a significant correlation between the TVB-N value and the spoilage flora, and the TVBN value increased as the degree of microbial infection in the meat quality increased35. According to Chinese national standards, the TVB-N value of fresh meat is less than 20 mg/100 g. The effect of OSP on TVB-N during the refrigerated period of beef patties is shown in Fig. 4. OSP addition significantly reduced the degree of microbial infection in beef patties. With the extension of storage time, the growth and reproduction of microorganisms, and the degradation of beef protein by microbial and endogenous enzymes into volatile alkaline substances, the TVB-N increased gradually. On 6 day, the beef patties in the control group exceeded the level 1 fresh meat standard (the national standard stipulates that < 15 mg·100 g−1 is level 1 fresh meat). Subsequently, on the 9 day, only 2.0%, 3.0% OSP, and AA groups still met the fresh meat standard for grade II (< 20 mg·100 g−1) compared to the other groups. On the 9 day, meat samples of the control and 1.0% OSP reached the standard of spoilage meat (> 25 mg·100 g−1). Thus, when compared to the control, the TVB-N value of beef patties treated with 2.0% OSP (21.33 mg·100 g−1) and 3.0% OSP (20.99 mg·100 g−1) was significantly lower. In addition, the results of both groups were lower than those of the AA group (22.73 mg·100 g−1). This indicates that OSP is superior to the AA. This may be attributed to the fact that onions are a natural source of flavonoids, specifically quercetin and anthocyanins, which significantly contribute to the antibacterial effect20. Consequently, the reported antibacterial properties of such substances have piqued the interest of the food industry in using them as antibacterial ingredients to improve food stability and prevent microbial spoilage37.

Effect of OSP on TVB-N of beef patties during refrigerated storage. Different letters of a–d represent significant differences in different treatment groups at the same refrigeration time (p < 0.05); different letters of A–E represent significant differences in different refrigeration times at the same treatment group (p < 0.05).

Total plate count (TPC)

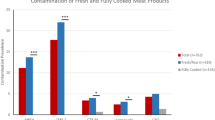

TPC is a sign that determines the degree of food contamination, which reflects whether the food meets the hygienic requirements in the production process. In addition, the total plate count, to some extent, marks the quality of food hygiene33. Figure 5 depicts the effect of OSP addition on the TPC of beef patties during cold storage. The results showed that the TPC in all treatment groups increased with the storage time. Adding OSP to beef patties could reduce the TPC compared to the control group, and the TPC decreased gradually with increasing OSP addition. Compared with the control, the addition of OSP in beef patties inhibited the increase of the TPC, and with the rise of OSP addition, the TPC in beef patties decreased significantly (p < 0.05). In all of the treatment groups, the lowest TPC was found in beef patties supplemented with 3% OSP during the storage period. According to China's national standards, the TPC in fresh meat reaches 7 log10 CFU/g, which is identified as spoilage meat. On day 9, the TPC value in the control exceeded 7 log10 CFU/g, reaching the spoilage meat limit, while the TPC in the beef patties with 3.0% OSP reached only 84.29% of that limit. When stored for 12 days, the TPC of all treatment groups exceeded the spoilage meat limit (7 log10 CFU/g). The above results showed that adding OSP to beef patties could inhibit the growth of microorganisms and slow down the spoilage process. Santas et al.1 reported that onion skin extract showed good antibacterial activity, including significant antibacterial effects against Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus, Micrococcus luteus, and Listeria monocytogenes. Irkin et al.38 found in their study on onion flavonoids that major flavonoids, quercetin-4'-deglucoside, quercetin-3, 4'-diglycoside, quercetin-7, 4'-deglucoside and isosaccharide had strong antibacterial activity against microorganisms. In addition, onion peel extracts have also been reported to have antibacterial activity against E. coli and mycosis in fresh beef38.

Effect of OSP on total plate of beef patties during refrigerated storage. Different letters of a–c represent significant differences in different treatment groups at the same refrigeration time (p < 0.05); different letters of A–E represent significant differences in different refrigeration times at the same treatment group (p < 0.05).

Effect of OSP on the physical properties of beef patties

Color of beef patties

The color of meat products is an important indicator to evaluate the quality of meat. It is the most commonly used standard for consumers to judge the shelf life and acceptability of meat. It is also the most essential appearance factor in determining consumers' desire to buy1. The color parameters of the beef patties included L*, a*, and b*; accordingly, ΔE was calculated. The results are shown in Table 2. With the increase in storage time, a* was observed to decrease gradually. Accordingly, on day 0, the a* of beef patties treated with OSP was significantly reduced in comparison to the control and the AA treatment group. At the end of storage, the a* value of the control decreased from 14.0 to 12.5, while the a* value of the 3.0% OSP group decreased from 8.2 to 5.4. Redness is the most significant color parameter for assessing meat oxidation, and the decrease in a* is due to the transformation of bright red OxyMb into brown MetMb31. The decrease in L*, a*, and b* in the OSP treatment group was primarily due to the infiltration of purple pigment from onion skin into beef muscle fiber. Nonetheless, the addition of OSP maintains the color stability of beef patties, as shown by ΔE. In contrast, the browning of meat diminishes its appeal to consumers. As natural plant extracts contain polyphenolic compounds, different types of plant extracts had different effects on the color of fresh pork, as measured by L*, a*, and b*29. Kurt et al.3 reached a similar conclusion that the L* of the control sample was the highest, whereas the L of the samples decreased at all storage stages following the addition of onion skin powder at varying concentrations. Moreover, as evident from previous studies, L*, a*, and b* of yellowed beef patties exhibited a decreasing trend after the addition of onion skin powder and cassis powder, which was attributed to the use of dense, dark brown and purple onion skin powder and cassis powder39. In conclusion, the pigment of plants has a significant effect on the color of meat products, and the number of additives and the selection of natural materials must be taken into account for practical application.

Texture profile analysis of beef patties

TPA is also known as the two-chewing test, which is used to examine the hardness, cohesiveness, elasticity, gelatinous nature, and chewiness of samples by simulating the chewing motion of the human mouth40. Table 3 shows the changes in texture characteristics of beef patties supplemented with OSP during refrigeration. When compared to the control and the AA treatment groups, the addition of OSP significantly enhanced the hardness, cohesiveness, springiness, gumminess, and chewiness of beef patties. In addition, on the 12 days, the 2.0% and 3.0% OSP groups exhibited the highest hardness (32.22N and 31.88N), cohesiveness (0.34 and 0.31), springiness (1.63 mm and 1.68 mm), gumminess (10.99A2/A1 and 9.88A2/A1), and chewiness [(12.74) G × mm and 13.25 g × mm], with no significant difference between them (p > 0.05). This suggests that 2.0% OSP was the maximum permissible additive level in beef patties and that the hardness of beef patties is not significantly affected by increasing additive levels. The increase in hardness value also has a significant impact on the flavor of meat products, because it increases the energy required to chew food, as well as the energy required to chew food to a stable condition when swallowing. This results in an increase in the stickiness and chewiness of food. In this regard, Jiao et al.33 reported that beef containing juvenile kiwi polyphenols exhibited increased adhesiveness and elasticity, as well as more stable hardness, elasticity, and chewiness. Moreover, Öztürk and Turhan4 reported that the addition of pumpkin seed powder decreased the hardness of beef meatballs. With an increase in pumpkin seed powder from 3 to 6%, the elasticity and chewiness of meatballs decreased, while the elasticity of pumpkin seed powder increased from 6 to 12%. In addition, the texture parameters of meat products vary significantly depending on the composition, source, and quantity of non-meat ingredients in the formula.

Conclusion

This study systematically investigated the effects of OSP on the storage stability and sensory quality of beef patties. The OSP-adulterated samples were darker than the control samples, with lower L*, a*, and b* values. With an increase in storage time, beef patties oxidation increased, but the formation of TBARS was lower in the sample containing 3.0% OSP than in the control group. Concurrently, TVB-N and TPC were significantly reduced, and the shelf life of beef patties with 3.0% OSP could be successfully extended to the 10th day. Thus, OSP can be considered a natural and functional food additive, with the potential to be added to certain meat products, such as beef patties, to prolong their shelf life while retaining their inherent characteristics.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Sagar, N. A. & Pareek, S. Dough rheology, antioxidants, textural, physicochemical characteristics, and sensory quality of pizza base enriched with onion (Allium cepa L.) skin powder. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 18669 (2020).

Petcu, C. D. et al. Effects of plant-based antioxidants in animal diets and meat products: A review. Foods 12(6), 1334 (2023).

Kurt, Ş, Ceylan, H. G. & Akkoç, A. The effects of onion skin powder on the quality of cooked chicken meat patties during refrigerated storage. Acta Aliment Hung 48(4), 423–430 (2019).

Öztürk, T. & Turhan, S. Physicochemical properties of pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L.) seed kernel flour and its utilization in beef meatballs as a fat replacer and functional ingredient. J. Food Process Pres. 44(9), e14695 (2020).

Mehdizadeh, T. et al. Chitosan-starch film containing pomegranate peel extract and Thymus kotschyanus essential oil can prolong the shelf life of beef. Meat Sci. 163, 108073 (2020).

Shim, S. Y. et al. Antioxidative properties of onion peel extracts against lipid oxidation in raw ground pork. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 21(2), 565–572 (2012).

Cheng, J. et al. Effects of mulberry polyphenols on oxidation stability of sarcoplasmic and myofibrillar proteins in dried minced pork slices during processing and storage. Meat Sci. 160(1), 1–10 (2020).

Oliveira, N. S. et al. Effect of adding Brosimum gaudichaudii and Pyrostegia venusta hydroalcoholic extracts on the oxidative stability of beef burgers. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 108, 145–152 (2019).

Dziki, D. et al. Current trends in the enhancement of antioxidant activity of wheat bread by the addition of plant materials rich in phenolic compounds. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 1(40), 48–61 (2014).

Muíno, I. et al. Valorisation of an extract from olive oil waste as a natural antioxidant for reducing meat waste resulting from oxidative processes. J. Clean Prod. 140, 924–932 (2017).

Pateiro, M. et al. Guarana seed extracts as a useful strategy to extend the shelf life of pork patties: UHPLC-ESI/QTOF phenolic profile and impact on microbial inactivation, lipid and protein oxidation and antioxidant capacity. Food Res. Int. 114, 55–63 (2018).

Prommachart, R. et al. The effect of black rice water extract on surface color, lipid oxidation, microbial growth, and antioxidant activity of beef patties during chilled storage. Meat. Sci. 164, 108091 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Effect of mulberry leaf extracts on color, lipid oxidation, antioxidant enzyme activities and oxidative breakdown products of raw ground beef during refrigerated storage. J. Food Qual. 39(3), 159–170 (2016).

Ghimire, A., Paudel, N. & Poudel, R. Effect of pomegranate peel extract on the storage stability of ground buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) meat. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 154, 112690 (2022).

Ivane, N. M. A. et al. Characterization, antioxidant activity and potential application fractionalized Szechuan pepper on fresh beef meat as natural preservative. Meat Sci. 208, 109383 (2024).

Mtibaa, A. C. et al. Enterocin bacFL31 from a safety Enterococcus faecium FL31: Natural preservative agent used alone and in combination with aqueous peel onion (Allium cepa) extract in ground beef meat storage[J]. Biomed. Res. Int. 1, 1–13 (2019).

Babaoglu, A. S. et al. Assessment of garlic and onion powder as natural antioxidant on the physico- chemical properties, lipid-protein oxidation and sensorial characteristics of beef and chicken patties during frozen storage. Arch. Lebensmittelhyg 74(4), 120–127 (2023).

Bedrníček, J. et al. Onion waste as a rich source of antioxidants for meat products. Czech J. Food Sci. 37(4), 268–275 (2019).

Bedrníek, J. et al. Thermal stability and bioavailability of bioactive compounds after baking of bread enriched with different onion by-products. Food Chem. 319, 126562 (2020).

Kumar, M. et al. Onion (Allium cepa L.) peel: A review on the extraction of bioactive compounds, its antioxidant potential, and its application as a functional food ingredient. J. Food Sci. 87(10), 4289–4311 (2022).

Bozinou, E. et al. Evaluation of antioxidant antimicrobial, and anticancer properties of onion skin extracts. Sustainability-Basel 15(15), 11599 (2023).

Michalak-Majewska, M. et al. Influence of onion skin powder on nutritional and quality attributes of wheat pasta. Plos One 15(1), e0227942 (2020).

Zahid, M. A. et al. Effects of clove extract on oxidative stability and sensory attributes in cooked beef patties at refrigerated storage. Meat Sci. 161, 107972 (2020).

Biswas, A. K., Chatli, M. K. & Sahoo, J. Antioxidant potential of curry (Murraya Koenigii L.) and mint (Mentha Spicata) leaf extracts and their effect on colour and oxidative stability of raw ground pork meat during refrigeration storage. Food Chem. 133, 467–472 (2012).

Cui, H. et al. Effect of ethanolic extract from morus alba l leaves on the quality and sensory aspects of chilled pork under retail conditions. Meat Sci. 172(8), 108368 (2021).

Vuorela, S. et al. Effect of plant phenolics on protein and lipid oxidation in cooked pork meat patties. J. Agr. Food Chem. 53(22), 8492–8497 (2005).

Zengin, H. & Bayasal, H. A. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of thyme and clove essential oils and application in minced beef. J. Food Process Pres. 39(6), 1261–1271 (2015).

Basiri, S. et al. The effect of pomegranate skin extract(PPE) on the polyphenol oxidase(PPO) and quality of pacific white shrimp(Litopenaeus vannamei) during refrigerated storage. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 60(2), 1025–1033 (2015).

Bellucci, E. R. B. et al. Red pitaya extract as natural antioxidant in pork patties with total replacement of animal fat. Meat Sci. 171, 108284 (2021).

Bahmanyar, F. et al. Effects of replacing soy protein and bread crumb with quinoa and buckwheat flour in functional beef burger formulation. Meat Sci. 172, 108305 (2020).

Lee, M. A. et al. Kimchi extracts as inhibitors of colour deterioration and lipid oxidation in raw groundpork meat during refrigerated storage. J. Sci. Food Agr. 99(6), 2735–2742 (2019).

Chauhan, P. et al. Inhibition of lipid and protein oxidation in raw ground pork by terminalia arjuna fruit extract during refrigerated storage. Asian Austral J Anim 32(2), 265–273 (2018).

Hajlaoui, H. et al. Phytochemical constituents and antioxidant activity of Oudneya Africana L. leaves extracts: evaluation effects on fatty acids and proteins oxidation of beef burger during refrigerated storage. Antioxidants-Basel 8(10), 442 (2019).

Zhang, H. et al. The application of clove extract protects Chinese-style sausages against oxidation and quality deterioration. Korean J. Food Sci. An. 37(1), 114–122 (2017).

Jiao, Y. et al. Polyphenols from thinned young kiwifruit as natural antioxidant: Protective effects on beef oxidation, physicochemical and sensory properties during storage. Food Control 108, 106870 (2020).

Kim, Y., Kim, Y. J. & Shin, Y. Comparative analysis of polyphenol content and antioxidant activity of different parts of five onion cultivars harvested in Korea. Antioxidants-Basel 13(2), 197 (2024).

Naveena, B. M. et al. Comparative efficacy of pomegranate juice, pomegranate rind powder extract and bht as antioxidants in cooked chicken patties. Meat Sci. 80(4), 1304–1308 (2008).

Karabagias, I., Badeka, A. & Kontominas, M. G. Shelf life extension of lamb meat using thyme or oregano essential oils and modified atmosphere packaging. Meat Sci. 88(1), 109–116 (2011).

Aksu, M. et al. Effects of cemen paste with lyophilized red cabbage water extract on the quality characteristics of beef pastrma during processing and storage. J. Food Process Pres. 44(11), e14897 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Quality predictive models of grass carp(Ctenopharyngodon idellus) at different temperatures during storage. Food Control 22(8), 1197–1202 (2011).

Santas, J., Almajano, M. P. & Carbó, R. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of crude onion (Allium cepa, L.) extracts. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 45(2), 403–409 (2010).

Irkin, R. & Arslan, M. Effect of onion (Allium cepa L.) extract on microbiological quality of refrigerated beef meat. J Muscle Foods 21(2), 308–316 (2010).

Chung, Y. K. et al. Physicochemical and storage characteristics of Hanwoo Tteokgalbi treated with onion skin powder and blackcurrant powder. Korean J. Food Sci. An. 38(4), 737–748 (2018).

Mabrouki, S. et al. Texture profile analysis of homogenized meat and plant-based patties. Int. J. Food Prop. 26(2), 2757–2771 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was financed by the Project Universities Basic Scientific Research Project in Heilongjiang Province (No.145209325), and the Project of Characteristic Discipline of Processing Technology of Plant Foods in Heilongjiang Province (No. YSTSXK202304).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Cuntang Wang provided the idea and wrote the main manuscript text, Yuqing Wang did the experiments and wrote the main manuscript text, Xuanzhe An processed the data, Zengming Gao prepared figures and tables, Yang Song processed the data, Manni Ren processed the data, Jian Ren provided the idea and revised the main manuscript text, All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Wang, Y., Song, Y. et al. Effect of onion skin powder on color, lipid, and protein oxidative stability of premade beef patty during cold storage. Sci Rep 14, 20816 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71265-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71265-x