Abstract

Business enterprises are complex adaptive systems (CAS) subject to fragility caused by the non-linear effects of uncertain risk events. The regional bank collapses in the United States are a case in point. Recent papers have highlighted a shortcoming of the traditional risk management process, which focuses on compliance but considers neither the interdependence between complex risks nor the mechanism of their non-linear impact on the organization. A new perspective on Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) has instead called for a shift of mindset from mitigating risk to building resilience by honing a CAS view to contextualize, assess, and manage complex risks. But the building blocks needed for a CAS representation of ERM have not yet been systematically developed. Specifically, we are missing a typological inventory of risks and a mapping of risks onto the general structure of an enterprise. In this paper, we build an industry-agnostic inventory of plausible risk factors using information extraction on large scale text data. Additionally, we develop an understanding of risk-function and function-function interdependencies through a survey of top business managers. The result is a novel complex network view of enterprise risk called a Quantified Risk Network (QRN) that displays small-world properties and highlights internal company functions central to non-linear risk propagation mechanisms within the enterprise. The QRN draws attention to vulnerabilities in the enterprise structure such as risk-function connections measured by Edge Betweenness centrality. The generic QRN developed herein is a proof of concept and we advocate that enterprises build their own company-specific QRNs to identify highly connected and central functions in their company structure that could lead to cascading failure when specific risks arise. QRNs can contribute to the objective of building enterprise resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The research discipline of management and organizational theory was originally based in a mechanistic paradigm1,2, emphasizing principles of operational structure and accountability under generally direct assumptions of cause and effect. However, companies are sociotechnical systems that display all the characteristic attributes of a complex system3 such as interconnectedness4; adaptation5,6; nonlinearity, fragility and resilience7,8; emergence9; self-organization10; and uncertainty11. Over time, several fields within management have adopted the Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS) lens12,13,14,15,1655, but the field of risk management remains compliance-oriented and simplistic17,18.

A complex system view is relevant to risk management because the non-linear and uncertain impact of adverse events on companies is clearly observed in prominent events that have occurred within the last decade. Geopolitical conflicts, bank collapses, the pandemic, prolonged material and component shortages, supply chain blockages, and the global financial crises have all demonstrated the havoc that unexpected external events can wreak on companies, and this has reinforced the need for companies to build resilience through improved risk intelligence19.

There is growing recognition that risks are complex by nature, and recent calls to account for complexity in risk management emphasize interdependence between risks20,21,22,23,24. Most recent literature considers risk–risk interaction networks but does not consider risk-function or function-function interaction networks25. In other words, risk management theory recognizes one source of complexity (emerging from interacting risks) but falls short of recognizing the other (emerging from an enterprise’s organizational structure). Both are needed to make sense of how risks could propagate non-linearly across the enterprise26.

In this paper, we introduce Quantified Risk Networks (QRNs) as a view of a CAS enterprise subject to risks. QRNs connect external risks to the structure of the enterprise, thereby enabling us to visualize and investigate how the impact of external risks might propagate across the enterprise system. QRNs reflect pertinent risks for a company and highlight central functions of the enterprise, which have high risk exposure and through which impact can propagate. Therefore, QRNs advance the field of risk management from simplistic estimation of risk occurrence and impact towards a CAS view where firms can contextualize complex external risks27, estimate the typical responses of its internal structure, and understand the thresholds beyond which the system could change states. This brings to forth the concept of resilience from CAS theory that is highly relevant to risk management research26. In the next section we describe the enterprise CAS and highlight the gap in the risk management literature.

The enterprise CAS

An enterprise can be viewed as a CAS operating within a larger CAS, which we refer to as its business environment or operating context28. To contain our research at the company level of analysis, we draw a boundary between the CAS enterprise (alternatively referred to as the company or the organization) and the operating context. Practically, this boundary is the domain of the focal company, i.e., the point beyond which the company has no direct control, although factors beyond the boundary may still, and often do, have a direct impact on the company. External factors collectively form the operating context and can be grouped under themes such as market dynamics, competition, regulatory environments, technological trends, economic conditions, and societal influences, which interact and create feedback, presenting both opportunities and challenges for the company. In this paper, we focus only on the challenges, which the literature generally refers to as risks.

Unexpected events occur in the company’s operating context subjecting it to multilayered risks29. They may arise individually or in tandem to impact the company’s normal functioning30. In this regard, resilience is the ability of the enterprise system to persist by maintaining essential functions and to evolve by incorporating change when confronted with unpredictable and unexpected events27. The company’s risk management function evaluates the operating context and responds. Managers monitor, identify, and assess risks, and contextualizing them is important for shaping tactical and strategic decisions under uncertainty27. This falls under the remit of enterprise risk management (ERM)31, making it crucial to building resilience and to the company's long-term success.

A CAS view of ERM

The literature on managing uncertainty in organizations dates to the seminal work of Frank Knight 32, who defined uncertainty based on ‘knowledge’ and broadly divided it into the knowable and unknowable. Knowable situations lead to a probabilistic view, where known probabilities of occurrence and their impact quantify the ‘risk’ to the company. In contrast, uncertainty includes those factors and situations that are epistemically difficult or impossible to know, i.e., unknowable unknows. Hence, from the Knightian perspective, quantifying uncertainty requires converting the unknown situations or factors into a tangible quantification of risk for the company33.

Risk management theory is grounded in the Knightian perspective and has evolved from a compliance-driven estimation and mitigation of risks to Enterprise Risk Management (ERM)—a more holistic approach to managing any risk that can potentially inhibit the enterprise from achieving its strategic objectives34. Thus, ERM blurs the boundary between uncertainty and risk. In doing so, ERM moves risk management scholarship from simple linear cause and effect towards a complex system view.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) published ISO 31000:2009, a framework for ERM, which although progressive in comparison to earlier frameworks, is simultaneously criticized for offering limited guidance on the challenge of identifying and contextualizing complex risks27. An amended framework issued in 201735 connects ERM with strategy by anchoring it to the context of a corporation’s performance23,36, but the ERM process still involves converting uncertainty into risk by estimating occurrence probabilities and determining impact. Note that ERM recognizes two sources of uncertainty- unexpected events and unexpected impact, and the ERM process suggests quantifying them into risk37.

However, when ERM is viewed as a CAS, complexity theory tells us that uncertainty and thus unpredictability is a consequence of the behavior of the system in which risk factors originate21. Therefore, knowing a priori how risks will emerge and how the enterprise CAS will respond to emerging risks requires understanding the ERM system and its states. Papers that call for the adoption of the CAS view on ERM recognize that risks are complex in nature, i.e., they form from feedback loops without pre-determined manifestation patterns. They correctly suggest that complexity theory can help us better understand limits of system states and changes in system states if unexpected events were to take place37. In other words, by adopting the tools of complexity theory, risk managers can identify those factors that destabilize the system and better understand the points at which the system becomes unstable and/or changes states. This is a novel approach to ERM when compared to simply estimating the probabilities of occurrence of individual risks 20,23. However, proponents of the complexity view emphasize much less the estimation of the impact that complex risks will have on the enterprise, given that the functions of the enterprise are themselves interconnected and interdependent. In this sense, the literature does not consider the role of the enterprise’s organizational structure in contributing to the non-linear behavior of the enterprise CAS38,39. CAS theory indicates that singular or simultaneous events manifesting in the company’s business environment will likely have a non-linear impact on the company, which could in turn lead to cascading consequences. In practice, the company’s risk managers, who have agency to make tactical and strategic decisions, would be expected to respond to curb the non-linear negative impact.

The CAS view on risk management is important because it can highlight the points and mechanisms of fragility for the company, and this is particularly critical for interdependent risks. Schiller and Prpich38, for example, emphasize that “Whereas independent risks generally follow Gaussian distributions, interdependent risks represent Paretian distributions, which represent extreme system behaviours or black swan events. ERM guidance has not yet accounted for these alternations in risk character.” Although the CAS view on ERM suggests non-linear impact of risks on the organization—and scholars have suggested that “the correlations between risks in different parts of an enterprise must be recognized, accounted for, and appropriately managed”34, there remains a gap in research towards understanding the mechanism of non-linearity and its measurement. We hypothesize that advancing the CAS view thus requires internal focus on the enterprise structure as dependencies between various enterprise functions propagate the negative impact of manifesting external risks. In this paper, we seek to understand and quantify how non-linearity is formed and propagated within the enterprise.

For CAS theory to be adopted into ERM practice, the field needs foundational elements (a comprehensive organized inventory of external risks and a generic enterprise structure with functional interdependencies, in light of the risks) to identify risks and assess their non-linear impact on an interconnected organization17. In this paper we address both gaps by building the foundational elements and demonstrating a process to identify risks, risk-function and function-function interactions. We analyze the functions of a generic enterprise that are more (or less) central and the risk-function edges, which connect dense clusters in the enterprise. Following principles of network theory, we hypothesize that business functions that are more central to the enterprise in the context of risk events are more likely to lead to the non-linear impacts that organizations experience when risk events manifest. Below we explain our representation of the risk management function as a CAS.

Representing ERM as a CAS

A CAS involves interacting components / agents that learn and adapt40. Thus, the two building blocks of a CAS are components and the interactions between them, which give rise to emergence as the dynamics of a CAS proceeds41. Network analysis is one of the methods to analyze CAS where components and interactions are represented as the nodes and links of the network, respectively. Then, in a CAS view of ERM, groups of risks and business functions (nodes) interact in interdependent ways to produce enterprise-wide effects, which can demonstrate cascading behavior across the CAS. All CAS share four major features: parallelism, conditional action, modularity, and adaptation and evolution42. Table 1 describes each of them and translates the described behaviors into the context of ERM, and thereby helps us translate the conceptual features of a CAS into the CAS view of ERM. However, from a practical standpoint defining the ERM as a CAS requires identification of the nodes of the ERM function and their interdependencies.

For the ERM CAS, nodes are the external risk factors occurring in the business environment as well as the various business functions such as finance, operations, strategic management, and product development that depend on one another for generating value in the enterprise. External factors variably impact business functions. For instance, a supply chain blockage will influence the manufacturing and distribution operations, which may also influence the company finances / cash flow 38. An inventory of external risks is needed to understand the external-internal interface. Most current studies that look at risk interdependencies rely on a handful and/or idiosyncratic set of risks25,43. In the methods section we describe how we built an inventory of risks and identified the risk-function and function-function interdependencies. Performing this process provides us with a general structure of a CAS organization and a first of its kind inventory of risk factors linked to it that is ready for complex network analyses.

Methodology

Data

A goal of this effort was to develop a comprehensive inventory of risk factors. Currently, company risk factor data is distributed across public and private sources and available in an unstructured form. A major public source of risk data is annual reports. The Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) mandates firms listed on US stock exchanges to provide risk disclosure in the Sections 1A and 7 of form 10-k filed annually. This data source has been used in studies on risk management44,45,46,47,48,49,50. We collected annual reports of roughly 15 years (up to year-2020) for companies listed in the S&P 500. In addition, we used a commercial data platform to access private analyst reports for the same companies, and gathered related information from the SCOPUS academic database.

Risk Extraction

The next step was to process the large volume of unstructured data to identify and organize risk factors into a typology. Risk factors in 10-k reports contain descriptive sentences, which may explicitly mention specific risk factors (e.g., currency risk, supply chain risk) or may implicitly provide risk information (e.g., “stoppages in material supply may cause a hindrance to our business objective”). We built a program leveraging natural language processing methods sequentially to extract relevant risk related information from sentences. We first extracted risk information content by tokenizing sentences into bi- and tri-grams and sought out syntactical patterns such as “Noun-risk” and “Noun-Noun-risk”51. This helped extract terms such as “currency risk” and “supply chain risk” while avoiding phrases such as “is risky”. The program used regular expressions52 to flexibly cover variations of words (e.g., risky). This provided us several explicitly stated risk factors. Second, we used the topic modeling technique to extract factors implicit in text sentences. The Sentence Latent Dirichlet Allocation (Sent LDA) is a popular topic modeling approach to infer risks as topics from sentences53,54. See the two referenced papers for the detailed Sent LDA algorithm. Lastly, we used the extracted factors as seed inputs into the SCOPUS database and further identified related risk factors provided as ‘author given keywords’ in the papers returned by the search. Not all author keywords were risk factors and required manual filtering. Overall, we extracted ~ 800 + risk factors, which is significantly larger than most published risk databases. The risk extraction process in pseudocode is as follows:

-

1.

For each firm \(f\in \left\{S\&P 500\right\}\), build a corpus \(C\) of text data on risk factors to firms

-

a.

Query the SEC Edgar database for 10-k reports

-

b.

Query the Refinitiv Eikon platform for commercial analyst reports

-

a.

-

2.

Use a bag-of-words approach to build the vocabulary

-

a.

For each document in \(C\),

-

i.

Tokenize sentences into bi-grams and tri-grams

-

ii.

Using spaCy and syntactic logic, extract risk factors and add to the inventory

-

i.

-

a.

-

3.

Identify latent topics in the corpus using SentLDA

-

a.

For each topic \(k\in \left\{1,\dots ,K\right\}\), draw a distribution over the vocabulary \({\beta }_{k}\sim Dirichlet\left(\eta \right)\)

-

b.

For each document \(\mathcal{d}\),

-

i.

Draw a vector of topic proportions \({\theta }_{d}\sim Dirichlet\left(\alpha \right)\)

-

i.

-

c.

For each sentence \(s\) in document \(\mathcal{d}\),

-

i.

Draw a topic assignment \({z}_{d,s}\sim Multinomial\left({\theta }_{d}\right)\)

-

i.

-

d.

For each word \({w}_{d,s,n}\) in a sentence \(s\),

-

i.

Draw a word \({w}_{d,s,n}\sim Multinomial({{\beta }_{z}}_{d,s})\)

-

i.

-

a.

where \({\beta }_{k}\) denotes the V-dimensional word distribution for the topic \(k\) derived by tokenizing the 10-k document; \({\theta }_{d}\) denotes the K-dimensional risk factor vector; and \(\eta\) and \(\alpha\) denote the hyperparameters of Dirichlet distributions.

-

4.

Manually review identified latent topics and add to the risk inventory

-

5.

Expand the risk inventory using the SCOPUS database

-

a.

Query SCOPUS and perform a combinatorial search of extracted risk inventory words

-

b.

For each paper in the returned set of papers

-

i.

Isolate the ‘author given keywords’ JSON object

-

ii.

Manually review and add to the risk inventory

-

i.

-

a.

Figure 1 provides a schematic process view of our complete methodology.

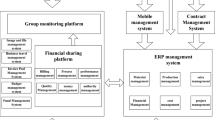

Organizing risk factors into a risk typology

Our objective was to link external risk factors to internal enterprise structure. For this, we organized the above inventory of risk factors into a typology. We used a top-level organizing structure described in existing literature on value-based strategy to link risk types to a generic organization represented as a system of value exchange. The value-based view in strategic management emphasizes the creation and enhancement of shareholder value as the primary objective of a company’s strategic decisions and actions. Thus, the activities performed by all companies fulfill a shared set of functions that can be linked back to value. The eight value functions include ‘manage value’, ‘identify value’, ‘convey value’, ‘create value’, ‘deliver value’, ‘capture value’, ‘protect value’, ‘sustain value’55 (See the referenced paper for a detailed description). This structure forms the basis of our contribution, which is to determine how business function interdependence leads to cascading impact of external risks.

A manual thematic analysis process was adopted to build a 5-level typology, where level 5 risk factors are clustered based on similarity, which are a type-of level 4 risk, which in-turn are a type-of level 3 risk group. Risk groups are linked to an enterprise’s generic functions at level 2, and functions are linked to one of eight value functions at level 1. Figures 2 and 3 show this organized typology of risks to any company.

Overview of risk-factor inventory. The background figure is a zoomed-out view of the full typology organized under the 5-level value structure with the 800 + risk factor inventory identified through text analysis on the perimeter. The box shows a zoomed-in view of level 5 risk factors for one branch of the typology related to geopolitical uncertainties.

Network development and network analysis

With the risk inventory mined and typology developed, our next step was to build the function-function and risk-function interlinks. For this we developed a survey, which was administered to 65 managers in large companies with different functional expertise. Subjects were selected based on designation. The preset criteria was to invite only middle-management level and higher. The distribution of responses by designation and company size is shown in Fig. 7. Subjects were recruited leveraging personal networks of the authors as well as through the Purdue University alumni network. A snowball sampling method was used by requesting experts who agreed to participate to forward the survey to colleagues in their networks who they deemed appropriate based on the criteria. The survey is provided in the attached supplementary materials, where a live link to the survey is also available.

Each subject matter expert quantified on a 0–100% slider scale how the business function of their expertise impacted other business functions within the organization. Further, each expert was asked to rate the level of impact caused by sets of risks on the business function/s of their expertise. This was kept as a fuzzy quantification exercise using ‘high impact’, ‘medium impact’, and ‘low impact’ ratings to provide ease of use and incentivize survey completion. With these two ratings, we were able to develop a generalized CAS network for analysis. Previous studies in ERM have used similar survey techniques to build risk networks56,57,58,59. Figure 4 highlights the processes to develop the QRN as they relate to the creation and structure of the risk inventory. The QRN in Fig. 5 represents a general complex network to capture the impact of external risks on a CAS enterprise. The descriptive statistics in Table 2 below summarize the QRN and describe its structure.

Directed network representations of function-function and risk-function relationships: (a) A directed network showing function-function impact. Orange nodes show L3 business functions (18) where the node sizes are ordered by the out degree of the node, i.e., how many other functions it impacts, and edge width and darkness represent higher impact weights indicated by experts.  Level 3 business functions ordered by out degree,

Level 3 business functions ordered by out degree,  Edges show direction of impact between enterprise functions. The edge width and darkness increase with higher impact values indicated by experts (b): Three views of a directed network showing risk-function edges. The left (Fig. 5b1) shows all 57 risk categories (right stack) connected to 18 functions (left stack) ordered top down by out degree. The darker lines denote the high impact of specific risks on functions as indicated by experts and the thicker edges represent greater edge betweenness centrality for that edge. 5b2 and 5b3 show risk-function edges filtered by level of impact. The middle (Fig. 5b2) (with purple edges) shows groups of high impact – high EBC edges between risks and functions, which should be continuously monitored. The right (Fig. 5b3) (with light blue edges) shows groups of low impact risk-function pairs. Although few have high centrality (thickness), they should not be overlooked as they can play a role in cascades.

Edges show direction of impact between enterprise functions. The edge width and darkness increase with higher impact values indicated by experts (b): Three views of a directed network showing risk-function edges. The left (Fig. 5b1) shows all 57 risk categories (right stack) connected to 18 functions (left stack) ordered top down by out degree. The darker lines denote the high impact of specific risks on functions as indicated by experts and the thicker edges represent greater edge betweenness centrality for that edge. 5b2 and 5b3 show risk-function edges filtered by level of impact. The middle (Fig. 5b2) (with purple edges) shows groups of high impact – high EBC edges between risks and functions, which should be continuously monitored. The right (Fig. 5b3) (with light blue edges) shows groups of low impact risk-function pairs. Although few have high centrality (thickness), they should not be overlooked as they can play a role in cascades.

Last, we applied network topology measures to analyze the QRN61,62. Though network analysis-based approaches have been adopted in risk management43,58,59, they have largely focused on creating risk interdependencies and estimating impact. This is a point of departure for the approach adopted herein, which builds the complex enterprise network structure and focuses on understanding the impact of risks, given a complex network topology. Measures from Network Theory are used including node degree and edge betweenness centrality. Node outdegree is the number of edges directed out from a node in the network, and we use it to quantify how many other functions each enterprise function impacts. In network analysis, ‘Betweenness’ is a centrality measure, i.e., how central a node is to the network, or said differently, how much is the network dependent on a node for propagation63. It is typically measured as the count of the paths between node pairs in a network that pass through a given node. Thus, nodes with high betweenness lie on paths between many others and will likely have some influence over the spread (of risk impact) across the network64,65. We use a specific centrality measure called Edge Betweenness Centrality (EBC). The EBC of any connected edge \(e\) is defined as the number of shortest paths between a node pair \(\left(s,t\right)\) that go through \(e\) divided by the total number of shortest paths that go from \(s\) to \(t\). Like betweenness centrality in nodes, EBC provides an intuition for edges that lie on central paths in a complex network. Edges with high EBC therefore connect dense sub-networks and help identify community structures in networks66. This is important as the impact of risks in contained sub-networks could propagate through an edge with high EBC.

Results

The methodology outlined above resulted in two major outputs: a structured inventory (typology) of 800 + risks, and a Quantified Risk Network (QRN), which is a weighted graph linking categories of identified potential risks to the functional structure (the system within managers’ control). A description of the results and a discussion follows.

The structured inventory is a novel resource and likely the largest organized database of risks to companies. Figure 2 illustrates a single branch of the risk along the value creation node. Given the wide breadth of coverage it is an obvious challenge to show all 800 + risk factors in a clear and concise manner. As an alternative, the background Fig. 3 captures the entire 5-level typology with the 800 + risk factors on the perimeter and the zoomed-in box illustrates inventory risks belonging to the geopolitical uncertainties category. Visit 28 to access the risk factor tables.

For clarity, the QRN is separated into Fig. 5a and b. Figure 5a indicates the complexity added by function-function interconnections. The larger orange nodes represent functions impacting the highest number of other functions. For example, Business strategy impacts 17 other functions whereas Market risk assessment impacts 10 other functions. They both impact the Competitive intelligence function similarly, but Business strategy has greater impact on the Marketing & sales function as compared to Market risk assessment (shown by the dark and light gray edges). An enterprise function when subject to external risks, will carry over the impact of the risk to connected functions, especially when it cannot contain the impact. This is a path or mechanism for risk propagation across functions.

Figure 5b shows three views of a weighted network connecting (57) level 4 risk categories to the (18) enterprise functions. Figure 5b1 captures all risk-function edges, whereas Figs. 5b2 and b3 show risk-function edges filtered by high and low risk impact indicated by experts, respectively. As expected, several high impact risks affect the most central nodes of the enterprise structure (top functions in the left column) with thick risk-function edges. These are top risks that should be continuously monitored. For instance, value chain stability risk causes high impacts on at least five functions and has high EBC edges. Further, the more central business functions are exposed to a broader and more diverse range of external risk factors. Even though several risks are marked as low-impact by experts (in Fig. 5b2), the thick edges indicate that there can be high EBC risk-function edges, albeit with risks considered to cause low impact on the enterprise. For example, corporate architecture risk has a seemingly low impact on sourcing. Yet that link is central to the network and can lead to a percolation or cascading impact across the enterprise if the function is unprepared or has a low threshold to manage the risk 67. Comparing Figs. 5b2 and 5b3, we should also note that the same categories of risk can impact different enterprise functions differently, thereby further reinforcing the necessity for cross-function communication among risk managers as has been called for by previous studies. The networks in Figs. 5a and 5b collectively give us a QRN, which managers can use to identify complex network effects as demonstrated above in addition to relying on consensus on what risks and functions should be monitored. This way they can uncover any missed risks or at least develop a shared language and perspective on risk factors to their enterprise that should be reviewed.

Figure 6 is a histogram plot of the EBC scores for risk-function edges. The EBC scores in our QRN are skewed towards lower EBC scores. There are some outlying edges with significantly high EBC scores. Table 3 lists the top 10 risk-function edges with highest betweenness centrality scores, bringing to light those specific risk-function pairs that are highly central to the QRN. They should be monitored as those edges connect dense parts of the QRN.

Lastly, the basic topology of the generic QRN developed herein points to features relevant to ERM. Watts and Strogatz60 empirically show that for similar values of characteristic path length (which measures the degree of separation in the network) and clustering coefficients (which are a measure of the cliquishness of the network) as found in our QRN (see Table 2), the network structure tends to be a small-world network. We suspect that enterprise risk networks in general and company-specific QRNs should also show a small-world network structure because by adding company-specific risk-function and function-function links, the clustering coefficient would further increase. Small-world networks have specific properties such as a hub-spoke structure and greater efficiency of flow in the network, which in the case of risk impact is a negative feature (Fig. 7).

QRNs form the basis for such complex network analyses. Having a QRN creates a mechanism for managing risks by connecting decontextualized risk knowledge to a company’s specific structure to interpret related impacts on its functions at a level that affects decision-makers. It shows the level of impact a risk category has on a business function and illustrates how firms can isolate and identify key functions that link densely connected risks and are therefore particularly significant to risk management.

Implications of a CAS view for ERM practice

A CAS view has been called for in ERM research. The CAS view looks at the holistic system and considers a broad spectrum of risks that could directly impact specific industries. For example, level 4 of the risk typology contains risk categories such as ‘geopolitical risks’, ‘product portfolio risks’, and ‘supply chain and operations risks’, which directly impact energy companies, companies engaged in developing physical and digital products, and companies engaged in manufacturing, respectively.

Further, the system view enables firms to look at beyond-industry risks, i.e., those risks that a company is exposed to indirectly and could affect it in reality but may not be considered major risks in its industry. Sheth and Sinfield19 illustrate cyber security risk impact to the shipping industry. Sheth and Kusiak16 illustrate this for manufacturing logistics, and Sheth28 illustrates this in the food processing industry.

Discussion

Three primary components serve at the core of ERM: risk identification, assessment, and risk mitigation. But the systems view in ERM suggests that these process steps need to be embedded in the enterprise’s context such that the monitoring of risks is systematic and not random27. The CAS approach is made complete by the development of a robust risk inventory and a company-specific QRN that enhance the ERM process.

Identification

A significant challenge for ERM is identifying weak signals within a company’s operating context23,68. The risk inventory developed herein is a novel resource for risk managers as it helps identify a large collection of plausible risks that may occur outside the company boundary in the company's operating context. Although not a full set, its broad coverage drawing on a large historic database allows for minimal periodic evaluation to keep it up to date. This is especially so because risks remain largely the same over time indicating that completely new risks are few and instead risk events occur with already known risks manifesting in new ways such as combinations of risks28. Thus, as managers monitor external threats, they have an enhanced ability to consider a broader set of risk factors and check across categories of risks for plausible interactions.

Assessment

Having a structured typology is foundational to creating a system view because it connects a missing component of earlier ERM frameworks – the contextualization of risks to the enterprise and related system feedback27. This helps sense-making and assessment of the impact of risks on the company. The typology is a bridge between risks external to the company and the organization of company functions.

The function-function links developed through expert input clarify how the organization’s activities are interconnected. This is a typical unknown in organizations and a source of uncertainty for the CAS. Similarly, function-risk links reduce the other traditional and significant source of uncertainty, i.e., how unexpected events affect functions. A quantification of function-function linkages and a fuzzy evaluation of risk-function linkages (high, medium, or low impact of risks on a function) enables easy practical application. Even without perfect quantification, companies can garner value from QRNs as they reveal dense clusters of related functions and points of fragility in the company. QRNs help leaders better understand their company’s vulnerability to risk events by illuminating those functions that are central to the value exchange system.

Moreover, QRNs reveal counter-intuitive insights, such as a function’s indirect exposure to risks typically associated with a different but connected function. These links within the company structure are the reason for the non-linearity of impact during external unexpected events as they enable the propagation or cascade of impact through the CAS. For example, the QRN reveals that ‘reputation’ and ‘sales execution’ risks have a high impact relationship with the ‘marketing and sales’ function. In turn, the ‘marketing and sales’ function is strongly linked to the densely clustered ‘financial capital management’ function. Hence, both reputation and sales execution risks are 1 hop risks that the financial management function should monitor even though they are not directly linked. Overall, applying network analysis methods over QRNs helps explore the threshold limits of the enterprise system and can be used to explore failure modes in CAS enterprises 69.

Mitigation

Developing a function driven and sector agnostic QRN offers a stepping off point for any organization to frame and develop its own QRN. Building a company specific QRN (following a similar procedure to that outlined above, but with entity-specific tailoring) enables planning for an adverse operating context, thereby advancing the risk management function. In addition, the process of developing company specific QRNs allows top managers across large organizations to clarify the differences in opinion on the significance of risk factors and on the potential impacts those could have on their company, which helps break down functional silos (which have plagued earlier ERM approaches). Thus, QRNs provide a shared language of risk management across CAS organizations.

Because the QRN is developed over a standard structure of business functions, this common basis provides opportunities for managers to learn from other organizations that share similar ways of fulfilling functions. This broadening of scope is novel because typically companies draw learnings from other companies operating in the same industry or sector. In addition, maintaining a watchful eye on companies outside of one’s sector that share ways of fulfilling business functions offers the potential to provide early awareness of weak signals not yet noticed in-sector.

Lastly, although the focus of this effort is on the challenges caused by external risks, honing an awareness of the precise location and mechanism of impact of manifesting challenges motivates the identification and pursuit of new opportunity because opportunities are often the inverse of challenges. Understanding the challenges clearly helps overcome them through more probable paths and can lead to opportunity capture.

Overall, the CAS view of organizations leads to advancement in traditional risk management of organizations that are operating in an increasingly interconnected and uncertain environment. Table 4 summarizes this comparison.

Limitations and Opportunities for Future Work

Using S&P 500 firms implied that the risk inventory would only contain risks impacting relatively large companies, only the risks faced by industries represented in S&P 500, and only those risks that were disclosed by them at least once. However, we took steps to partially overcome the bias induced by our choice. For instance, purchasing access to private analyst reports allowed us to identify additional risks undisclosed in public reports but mentioned in the investment analyses. Additionally, we used the identified risk factors as seed input into the SCOPUS academic database to run a second pass in identification. SCOPUS is one of the largest abstract indexing platforms and provides ‘author given keywords’ in each listed paper. As shown in Fig. 1, the iterative mining process discovered additional related risks indicated as keywords in academic papers related to the particular risk.

In terms of the coverage of the S&P 500, it comprehensively represents all economic sectors even though it does not have as much granularity at sub-industry level. This is a shortcoming, and in the future, the data source can be expanded to include a larger set of companies such as the Russell 3000 list, on which the extraction and expansion process can be applied.

The stated limitations highlight several opportunities for future research. First, the data processing methods employed herein did not use transformers or large language models, which future research can include to validate and improve our typology. Second, evaluation of the risk-function and function-function linkages highlighted in this work could further benefit from the perspectives of additional expert evaluators given the broad scope and complexity of the developed comprehensive risk inventory. Further, numerous opportunities exist to draw on the underlying structure of the sector agnostic QRN provided here to examine specific industries and companies and thus further validate and/or refine it for application across contexts. Furthermore, by simulating the network growth dynamic over time, we can potentially predict the cascading behavior in small-world networks by studying the degree distribution and the betweenness distribution 70. The simulation is not performed here because we do not have data on the threshold levels / impact absorption capacity of the enterprise functions. But collecting this data in a company-specific QRN building exercise will make it a promising path for future research on cascading failures and for the sensing of weak-signals indicative of cascading failure.

Conclusion

A specific takeaway of earlier ERM frameworks is that “risk management cannot be done in functional silos within an enterprise but instead must be a coordinated effort across organizational lines.”34 In this paper, we advance the CAS-view of ERM by providing a method for firms to enhance their risk monitoring as well as better contextualize identified risks, across organizational silos, by building QRNs. The paper has developed a generic QRN, which while not specifically focused on a company or industry, offers a) a robust starting point for risk identification, b) a complete sector-agnostic organizing structure for company functions, and c) demonstrates the steps to develop a company specific QRN. It is a proof of concept that analyzing QRNs yields valuable insight regarding the points of weakness in the enterprise risk network. The approach taken to build and analyze QRNs brings ERM closer to complex network analysis, which is called for by the ERM research community but not yet performed. Ultimately, it has merits over current simplistic approaches because it highlights the plausible mechanisms of impact cascades.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bohórquez Arévalo, L. E. & Espinosa, A. Theoretical approaches to managing complexity in organizations: A comparative analysis. Estudios Gerenciales https://doi.org/10.1016/j.estger.2014.10.001 (2015).

Turnbull, S. A New Way to Govern. SSRN Electron. J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.310263 (2002).

Anderson, P. Perspective: Complexity theory and organization science. Organ. Sci. 10, 216–232 (1999).

Chandra, Y. & Wilkinson, I. F. Firm internationalization from a network-centric complex-systems perspective. J. World Bus. 52, 691–701 (2017).

Teece, D. J. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management: Organizing for Innovation and Growth. (2009).

Pathak, S. D., Day, J. M., Nair, A., Sawaya, W. J. & Kristal, M. M. Complexity and adaptivity in supply networks: Building supply network theory using a complex adaptive systems perspective*. Decis. Sci. 38, 547–580 (2007).

Zhang, Y. & Yang, N. Vulnerability analysis of interdependent R&D networks under risk cascading propagation. Physica A 505, 1056–1068 (2018).

Taleb, N. N. Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder. (2012).

Stacey, R. D. The science of complexity: An alternative perspective for strategic change processes. Strateg. Manag. J. 16, 477–495 (1995).

Sheth, A. & Sinfield, J. V. Simulating Self-Organization during Strategic Change: Implications for Organizational Design. (2019).

Townsend, D. M., Hunt, R. A., McMullen, J. S. & Sarasvathy, S. D. Uncertainty, knowledge problems, and entrepreneurial action. Acad. Manag. Ann. 12, 659–687 (2018).

Puranam, P., Alexy, O. & Reitzig, M. What’s “new” about new forms of organizing?. Acad. Manag. Rev. 39, 162–180 (2014).

Baumann, O. Models of complex adaptive systems in strategy and organization research. Mind Soc. 14, 169–183 (2015).

Novak, D. C., Wu, Z. & Dooley, K. J. Whose resilience matters? Addressing issues of scale in supply chain resilience. J. Bus. Logist. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12270 (2021).

Choi, T. Y., Dooley, K. J. & Rungtusanatham, M. Supply networks and complex adaptive systems: Control versus emergence. J. Oper. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(00)00068-1 (2001).

Sheth, A. & Kusiak, A. Resiliency of smart manufacturing enterprises via information integration. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jii.2022.100370 (2022).

Sachs, R. & Wadé, M. Emerging Risk Discussion Paper: Managing Complex Risks Successfully. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267370113 (2013) https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.2128.8961.

Kassymkanova, G. Insurance Professionals’ Use of Best Practices for Enterprise Risk Management. (2023).

Sheth, A. & Sinfield, J. V. Risk Intelligence and the Resilient Company. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 64, (2023).

Johnson, J. Can complexity help us better understand risk?. Risk Manag. 8, 227–267 (2006).

Smith, D. & Irwin, A. Complexity, risk and emergence: Elements of a “management” dilemma. Risk Manag. 8, 221–226 (2006).

McKelvey, B. & Andriani, P. Avoiding extreme risk before it occurs: A complexity science approach to incubation. Risk Manag. 12, 54–82 (2010).

Emblemsvåg, J. Risk and complexity – on complex risk management. J. Risk Financ. 21, 37–54 (2020).

Andringa, L., Ökmen, Ö., Leijten, M., Bosch-Rekveldt, M. & Bakker, H. Incorporating project complexities in risk assessment: Case of an airport expansion construction project. J. Manag. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0001099 (2022).

Sasaki, H., Fujii, M., Sakaji, H. & Masuyama, S. Enhancing Risk identification with GNN: Edge classification in risk causality from securities reports. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 4, 100217 (2024).

van der Vegt, G. S., Essens, P., Wahlström, M. & George, G. Managing risk and resilience. Acad. Manag. J. 58, 971–980 (2015).

Haywood, L. K., Forsyth, G. G., de Lange, W. J. & Trotter, D. H. Contextualising risk within enterprise risk management through the application of systems thinking. Environ Syst Decis 37, 230–240 (2017).

Sheth, A. B. Pathways to Enterprise Resilience. (Purdue University, 2021). https://doi.org/10.25394/PGS.15062880.v1.

Ibrahim, S. E., Centeno, M. A., Patterson, T. S. & Callahan, P. W. Resilience in global value chains: A systemic risk approach. Global Perspect. https://doi.org/10.1525/gp.2021.27658 (2021).

Mark, S., Holder, S., Hoyer, D., Schoonover, R. & Aldrich, D. P. Understanding polycrisis: Definitions, applications, and responses. SSRN Electr. J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4593383 (2024).

Bromiley, P., McShane, M., Nair, A. & Rustambekov, E. Enterprise risk management: Review, critique, and research directions. Long Range Plann 48, 265–276 (2015).

Knight, F. H. Risk, uncertainty and profit (Hart, Schaffner and Marx, 1921).

Marshall, A., Ojiako, U., Wang, V., Lin, F. & Chipulu, M. Forecasting unknown-unknowns by boosting the risk radar within the risk intelligent organisation. Int. J. Forecast 35, 644–658 (2019).

Nason, R. Risk management and complexity. in It’s not complicated: the art and science of complexity in business 165–191 (2017).

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). COSO Enterprise Risk Management – Integrating with Strategy and Performance. (2017).

Viscelli, T. R., Hermanson, D. R. & Beasley, M. S. The integration of ERM and strategy: Implications for corporate governance. Account. Horiz. 31, 69–82 (2017).

Johansen, I. L. & Rausand, M. Defining complexity for risk assessment of sociotechnical systems: A conceptual framework. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. O J. Risk Reliab. 228, 272–290 (2014).

Schiller, F. & Prpich, G. Learning to organise risk management in organisations: What future for enterprise risk management?. J. Risk Res. 17, 999–1017 (2014).

Yang, L., Lou, J. & Zhao, X. Risk response of complex projects: Risk association network method. J. Manag. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000916 (2021).

Holland, J. H. Complex adaptive systems. Daedalus 121, 17–30 (1992).

Holland, J. H. Complex adaptive systems and spontaneous emergence. Contributions to Economics 25–34 (2002) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-50007-7_3.

Holland, J. H. Studying complex adaptive systems. J. Syst. Sci. Complex 19, 1–8 (2006).

Bashir, H. et al. A weighted fuzzy social network analysis-based approach for modeling and analyzing relationships among risk factors affecting project delays. EMJ – Eng. Manag. J. 36, 3–13 (2024).

Fujii, M., Sakaji, H., Masuyama, S. & Sasaki, H. Extraction and classification of risk-related sentences from securities reports. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2, 100096 (2022).

Loughran, T. & McDonald, B. When Is a liability not a liability? textual analysis, dictionaries, and 10-Ks. J Finance 66, 35–65 (2011).

Felipe Costa Spreb, L., Roussou, F., Marshall, A. & Mues, C. RISK RADAR : A METHODOLOGY TO CATEGORISE RISKS DISCLOSED ON SEC 10-K REPORTS. (2019).

Bode, C., Wagner, S. M., Zurich, E. & Kemmerling, R. Internal versus External Supply Chain Risks: A Risk Disclosure Analysis. In Supply Chain Safety Management – Security and Robustness in Logistics (eds Eßig, M. et al.) 109–122 (Springer, Berlin, 2013).

Mirakur, Y. Risk Disclosure in SEC Corporate Filings. https://repository.upenn.edu/wharton_research_scholars/85/ (2011).

Bao, Y. & Datta, A. Simultaneously discovering and quantifying risk types from textual risk disclosures. Manage Sci 60, 1371–1391 (2014).

Beatty, A., Cheng, L. & Zhang, H. Are risk factor disclosures still relevant? evidence from market reactions to risk factor disclosures before and after the financial crisis. Contemporary Account. Res. 36, 805–838 (2019).

Sheth, A. & Sinfield, J. V. Systematic problem-specification in innovation science using language. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 13, 314 (2021).

Mitkov, R. The Oxford Handbook of Computational Linguistics 2nd edn. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2014).

Zhu, X., Yang, S. Y. & Moazeni, S. Firm risk identification through topic analysis of textual financial disclosures. in 2016 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence, SSCI 2016 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/SSCI.2016.7850005.

Wang, Y., Li, B., Li, G., Zhu, X. & Li, J. Risk factors identification and evolution analysis from textual risk disclosures for insurance industry. Procedia Comput. Sci. 162, 25–32 (2019).

Liu, J., Tong, T. W. & Sinfield, J. V. Toward a resilient complex adaptive system view of business models. Long Range Plann. 54, 102030 (2021).

Marle, F. & Vidal, L. A. Project risk management processes: Improving coordination using a clustering approach. Res. Eng. Des. 22, 189–206 (2011).

Fang, C. & Marle, F. A framework for the modeling and management of project risks and risk interactions In Handbook on Project Management and Scheduling 1105–1117 (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

Fang, C., Marle, F., Zio, E. & Bocquet, J. C. Network theory-based analysis of risk interactions in large engineering projects. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 106, 1–10 (2012).

Fang, C., Marle, F. & Xie, M. Applying importance measures to risk analysis in engineering project using a risk network model. IEEE Syst. J. 11, 1548–1556 (2017).

Watts, D. J. & Strogatz, S. H. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature 393, 440–442 (1998).

Freeman, L. C. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. 1, 215–239 (1978).

Brandes, U., Borgatti, S. P. & Freeman, L. C. Maintaining the duality of closeness and betweenness centrality. Soc. Netw. 44, 153–159 (2016).

Vespignani, A. Predicting the behavior of techno-social systems. Science 1979(325), 425–428 (2009).

Newman, M. Networks (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2018).

Newman, M., Barabási, A. & Watts, D. The Structure and Dynamics of Networks (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2006).

Newman, M. E. J. & Girvan, M. Finding and evaluating community structure in networks. Phys. Rev. E 69, 026113 (2004).

Piraveenan, M., Prokopenko, M. & Hossain, L. Percolation centrality: Quantifying graph-theoretic impact of nodes during percolation in networks. PLoS One 8, e53095 (2013).

Shankar, R. K., Bettenmann, D. & Giones, F. Building hyper-awareness: how to amplify weak external signals for improved strategic agility. Calif. Manag. Rev. 65, 43–62 (2023).

Pournajar, M., Zaiser, M. & Moretti, P. Edge betweenness centrality as a failure predictor in network models of structurally disordered materials. Sci. Rep. 12, 11814 (2022).

Xia, Y., Fan, J. & Hill, D. Cascading failure in Watts-Strogatz small-world networks. Physica A 389, 1281–1285 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number 2049782.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ananya Sheth: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Formal analysis; Visualization; Writing—original draft, review & editing. Joseph V. Sinfield: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests as defined by Nature Research, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and/or discussion reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheth, A., Sinfield, J.V. Advancing the complex adaptive systems approach to enterprise risk management with quantified risk networks (QRNs). Sci Rep 14, 22312 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71764-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71764-x