Abstract

Damage caused to railway tracks and the surrounding environment during trains passage have become a real concern for those involved in the railway sector over the years. To find a solution for this problem, several approaches have already been implemented on railway tracks in some countries. Despite the efforts made in this area, the problem of ground vibration induced by railway traffic still remains a concern. Therefore, many studies have been focused on solutions to attenuate, even cancel vibrations effects on the track and nearby environment. This work has presented a modeling of a ballasted railway track with a shock-absorbing mat or Under Sleepers Rubber Mat (USRm) at the sleepers/ ballast interface. Using the equation of wave propagation in the ground and the constitutive law, the eigenfunctions of the displacement vector were determined. By coupling the equations of the track and those of the ground, the displacement, the velocity, and the acceleration of each track component, as well as the stress on the ground surface were expressed. The Newmark numerical method was used to represent these variables and to highlight the (USRm) influence on the dynamic behavior of the different track component. Comparison of the results obtained with the proposed railway model shows a reduction in vibration amplitudes of 64.9% and 94%for the rail, 86.5% and 56.25% for the sleepers. At the ground surface, the attenuation of vibration is evaluated at 53% and 6.85%, respectively for linear and nonlinear cases. The insertion of the shock-absorbing mat (USRm) in the railway track structure also reduces stress at the ground surface. The configuration of the railway track with a damping mat (USRm) therefore significantly reduces the transmitted vibration to the ground and to the nearby structures. It also contributes to the stability of the track and the improvement of its performance. The proposed railway track model with a shock-absorbing mat can be considered as a solution to reduce vibrations generated on track and the ground during trains passages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

From several decades, the train has been considered as a reliable means of mass transport for both people and goods. Although being a solution to the problems of mass travel, train transport is nevertheless the cause of certain problems on the railway infrastructure and on the immediate environment of the railway tracks. Indeed, vibrations due to train motion are able to destroy the railway structure as well as the surrounding environment and structures nearby. The frequent passage of trains carrying very heavy loads, the rail roughness and other railway irregularities can significantly contribute to the damage of the railway track structure. The damage suffered by the sleepers and the settlement of the ballast are likely to influence railway performance.

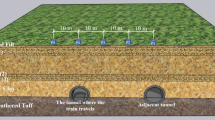

With the development of railway technology and engineering, ground vibration induced by high-speed trains can be excessive and become a nuisance to nearby residents, or affect the functioning of electronic equipment or even cause important damage to buildings1,2,3.

Several researches have been conducted towards to predict or effectively reduce the influence of the vibrations generated by railway traffic on the environment4,5,6,7.

Other studies have focused on improving the quality of the railway track and its performances. As a result, for several years, several countries in central Europe have opted for the use of resilient materials as rail pads, under ballast mats (UBM), under sleeper pads (USPs) in railway system to strengthen and improve track resiliency8. These under sleeper pads, classified in four groups by the bedding modulus are used as resilient materials among many intended to protect railways tracks9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Usually associated with concrete sleepers in railway track, USPs can also be used in several other domain of civil engineering. As under sleeper pads, the use of Under Sleeper’s Rubber Mat (USRm) can also contributed to improve railways protection and performances. These resilient materials mainly used to increase railway track vertical elasticity and reduce ballast friction and ground -borne vibrations also serve as vibration damper or insulator to protect ballast and ground for transmitted sleepers’ vibrations.

The rubber mat also protects ballast and ground surface against wheel / rail interactions effects by reducing the pressure exerted on ballast and also vibration of nearby areas and structures8. The insertion of this shock-absorbing mat between the sleepers and ballast increases their contact. This strengthening of contact leads to the reduction of stress transmitted from sleepers to the substructure layers16. The USRm also helps to uniform distribution of loads and mainly those created by the axles to more numbers of sleepers17. Several experimental studies have been carried out in order to highlight the influence of these resilient materials on vibration effects induced by the excitation of railway tracks.

Conventional railway superstructure, compared to the structures on timber have less contact elasticity between sleepers and ballast material. Ballast bed is therefore the weakest link in the entire track due to the crushed stone movements during dynamic loads. Their motion not only leads to a strong abrasive wear on areas of contact of single stone but also to breakings or even pulverization of some stone18. To solve this problem, it turned out to be necessary to opt for the modification of dynamic characteristics of vehicle-track structure. Today, several studies on railway tracks models integrate the use of USPs have been conducted to improve track performance. Experimental study carried out on the track with and without USPs showed that vibrations on track with under sleeper pads decreased up to 30%18. Finite element model (FEM) of track with under sleeper pads and field investigation into the vibration attenuation, characteristic of under sleeper pads have also been used to highlight the influence of USPs on the dynamic behaviour of track. Taking into account the train-track interaction, the study proved that soft USPs have a significant influence on the track’s dynamic behaviour; with the ability to amplify rail displacement and sleeper accelerations and also to protect ballast layer, and significantly reduce vibrations amplitudes at level of ballast and ground surfaces. The study also found that the sleepers with USPs tend to have lesser flexures, and hard USP may reduce sleeper-ballast friction19,20. In another study, discrete element modelling (DEM) of under sleeper pads has been used to emphasize the effects of USPs in the railway track. The results obtained showed that USPs increase the contact between ballast particle and the pad. They also permit a large lateral transfer of loads to the adjacent ballast but a smaller vertical load beneath the sleeper. The study concluded that USPs in the track contributes to reduce track settlement and effectively reduce particle abrasion that occurs in these regions21. A dynamic model of track with a USPs based on synthesizing sub-models of individual effects to study the influence of USPs in the transition zones built between sections of railway tracks has been developed22. The model used numerical integration techniques to solve the problem. The results of this study clearly showed that USPs can be perfectly used in transition zones, and, track configuration without USPs may be not appropriate, especially for high-speed trains.

In others previous works, alternatively to the fully well-known 3D model, an approach has been developed by some authors, taking into account some railway-track characteristics which allow solving the 3D problem using an efficient computational scheme known as 2.5D model. According to this concept, P. Alves Costa et al. have developed a 2.5D FEM–BEM model, coupling finite element method and boundary element method to solve problems of vibrations induced by traffic and train-track dynamic interaction23. Their results were compared to field measurements and they concluded that the model is adapted for track-ground problems. S. François et al. also used 2.5 D coupled finite element and boundary element methodology to solve a dynamic interaction problem between a layered soil and structures with a longitudinally invariant geometry24. Authors concluded that the model permits to only discretize the interface between the structure and the soil, reducing storage requirements with respect to the classical use of the fully space. Others authors have proposed a 2.5D finite/infinite element approach to model visco-elastic bodies subjected to moving loads25. They conclude that the model has four mains’ advantages. In another study, S. François et al. used a 2.5D coupled finite element–boundary element methodology to highlight the efficiency of vibration isolating screens. Their numerical results were compared with measurements for an existing vibration isolating screen and the numerical predictions turned out to be satisfactory26.

In this work, an analytical approach has been developed to predict the dynamic behavior of ballasted railway track with concrete sleepers and USRm. The dynamic responses of railway track component and ground surface under the ballast layer are highlighted. The railway track is excited by a harmonic load and the stress on the ground surface is determined from the scalar and vector potentials of the displacement.

Track modelling

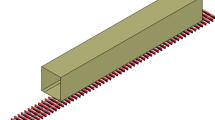

To carry out our study, we considered a continuous simplified ballasted railway track model as that described in27. For this type of model, at low frequences, the length of the deflection wave of the rail under the load is grater than the spacing between each sleeper27. This track is made up of two rails, pads, sleepers, ballast and a shock-absorbing mat inserted between sleepers and the ballast to serve as an insulator and vibrations damper.

The rail of mass \({m}_{R}\) is assimilated to an Euler–Bernoulli beam of bending rigidity \(EI\), the sleepers of mass \({m}_{S}\) are linked to the rails by pads of stiffness \({k}_{p}\) and damping coefficient \({\eta }_{p}\).These elements are resting on the ballast layer which characteristics are: mass \({m}_{B}\), damping coefficient \({\eta }_{B}\) and stiffness \({k}_{B}\). These different elements are represented in Fig. 1.

Equations of motion

In the fixed coordinate system \(\left( {O,x_{1} ,x_{3} } \right)\),the movement of the rail is described by an equation of bending vibration of an Euler–Bernoulli beam subjected to the simultaneous effects of the harmonic load and the distributed force created by pads17,27,28,29,30,31.

For the sleepers, we used a distributed and continuous mass over the entire track. The spacing between these sleepers is neglected because at low frequencies, this spacing is smaller than the wavelength of the rail under the load31. The motion of the sleepers of mass \({m}_{S}\) is then represented by the dynamic equation17,27,28,29

The presence of a shock-absorbing mat at the sleepers- ballast interface creates a restoring force at the ballast upper side. This force is represented by the equation:

The ballast layer is in contact with the sleepers and the ground respectively at it upper and lower sides. The equations of motion are then written, taking into account the sleeper-ballast interactions between which the shock-absorbing mat is introduced, and also the ballast-ground contact. These interactions are translated by the equations:

Therefore, the railway track motion can be represented by the following system of equations:

These equations can be rewritten in the form:

Using the matrix form of Eq. (6), we obtain:

Ground motion equations

The ballast underside is in contact with the ground. The propagation of waves on their surface of contact is governed by the three equations31,32,33,34,35,36,37

where \(\lambda {\text{ and }}\mu\) are Lamé constants and respectively defined by:

\(\overrightarrow {u}\) is the displacement vector given by the expression, \(E{\text{ and }}\nu\) are respectively the young modulus and Poisson ration of the material.

where \(\Phi\) and \(\Psi\) are respectively the scalar and the vector potentials of Helmholtz. Replacing the displacement field by its expression (11) into Eq. (8) and (9), one obtains:

We obtain:

And:

For a two-dimensional (2D) problem, considering horizontal direction \(x\) and vertical direction \(z\) , one can write:

With:

Considering that the two potentials are harmonic, we can rewrite the system of Eqs. (15) in the form:

with:

The system of Eqs. (16) can now be written as:

Either, the system of Eqs. (18) is an eigenvalue problem38; and it will be solved to determine eigenfunction \(\Phi and\Psi\).

Considering the expressions:\(\Phi \left(\text{x},\text{z}\right) and\Psi (\text{x},\text{z})\) and assuming that:\(\Phi \left(\text{x},\text{z}\right)=f\left(x\right)g(z)\), we can write:

The substitution of Eq. (19) into Eq. (20), leads to:

Hence, Eq. (21) yields to following form:

All the details of mathematical development to obtain the solution of Eq. (23) are presented in Appendix A.

According to general properties of eigenmodes of \(\Delta\) and eigenvalues \({\lambda }_{k}\), eigenvalues are positives reals38.

After some mathematical transformations, the scalar potential and the vector potential are determined. The details related to the derivation to determine eigenfunctions are mentioned in Appendix A.

Assuming that railway is as a rectangle, with dimensions \(\left[0 {L}_{x}\right]\times \left[0 {L}_{z}\right]\), and applying boundaries conditions, we are able to determine the corresponding expressions of eigen functions \(\Phi (x,z)\) and \(\Psi (x,z)\).

By applying, the mixed boundary conditions on the edges of the railway track and considering that displacements and strength are respectively equal to zero at the origin and the end of the railway track, we can write for the function \(\Phi\):

Hence, the arbitrary functions \(\text{f and g}\) are given by:

The general expression of the scalar potential can then be written:

Using the same reasoning, we can determine the general expression of the vector potential \(\Psi\).

This solution can also be written as:

By replacing the scalar and vector potential by their respective expressions we obtain:

At the ground surface \(z=0\) we admit that \(\sigma_{xz} = 0\) and \(\sigma_{zz}\) is equal to the strength exerted by the ballast on the ground27,28,29,30,31: so that:

The mathematical developments which make it possible to determine the expression of the vertical stress \(\sigma_{zz}\) are recorded in Appendix B.

Therefore,

Using the expressions of Lamé coefficients \(\lambda\) and \(\mu\):

We obtain at the ground surface:

We can now rewrite the system of Eq. (5) as follow:

To solved the system of Eqs. (32) Newmark numerical integration has been implemented. The main steps of this procedure are presented in section "Newmark method"

Newmark method

In this section, we present the Newmark numerical integration method40 whose objective is to evaluate at the level of the rail, the sleepers and the ground, the displacements, velocities and accelerations induced during the passage of a train considered as a dynamic load on a ballasted railway track modeled as a 2D idealization.

From Eq. (31), we introduced three unknowns: \(w^{m}\) denotes the approximation of the displacement field vector \(w = \left\{ {w_{R} ,w_{S} ,w_{B} } \right\}^{t}\) at time \(t_{m}\) ; \(\dot{w}^{m}\) is the approximation of the velocity \(\dot{w} = \left\{ {\dot{w}_{R} ,\dot{w}_{S} ,\dot{w}_{B} } \right\}^{t}\), at instant \(t_{m}\) , and \(\ddot{w}^{m}\) is approximation of the acceleration \(\ddot{w} = \left\{ {\ddot{w}_{R} ,\ddot{w}_{S} ,\ddot{w}_{B} } \right\}^{t}\) at the moment \(t_{m}\). The method uses two parameters β and γ in [0; 1]. Thus, we rewrite the system of differential Eq. (38) as follows:

Using the Newmark scheme, Eq. (33) can now be written as:

In the absence of non-linearity, which means by neglecting the flexural rigidity of the rail, Eq. (34) becomes:

The initial conditions are as follows

These are the forms of Eqs. (34) and (35) which have been used to analyze the effects of the different kinematic parameters of the rail, sleepers and ground in the linear and non-linear domain.

Results and discussion

This section is devoted to railway track behavior analysis. Accurately, our aim is to highlight the displacement, the velocity and the acceleration of railway components as well as the supporting ground, from the proposed railway track model and the conventional one without a shock-absorbing mat.

Validation of the proposed model

The validation of the proposed model is based on the literature review. The effects of USPs on the dynamic behaviour of the different elements of the railway track and the comparisons made with experimental and numerical studies which have already been the subject of several articles. Indeed, several authors have highlighted the importance of USPs in the dynamic behaviour of railway track. Chayut et al.9 used a 3D finite element model of prestressed concrete sleepers with USPs to show that sleepers with USPs tend to have lesser flexures, contact force and impact energy. The also concluded that, the vibration of sleeper with USPs could be amplified by the large amplitude impact force induced by high-speed strains. In a previous study, Li Wang et al.39 used a 3D finite element model to investigate ground vibration induced by high-speed trains on an embankment with pile-board foundation. The showed that soil Young’s modulus and soil impedance are the two main factors influential to the local vibration amplification. They concluded that, the softer the natural soil, the larger the amplification. Others experimental and numerical studies showed that USPs have a significant influence over the track’s dynamic behaviour; increasing vibration of both rail and sleepers, amplifying sleeper acceleration, protecting ballast layer, reducing sleeper-ballast friction and significantly reducing vibrations amplitudes at the ballast and ground surfaces. The presence of USPs in the railway track improves its performance and leads to the track stability19,20. The results obtain with the proposed model are compared with those of the conventional model and the literature, taking into account the effects of the USPs in the railway track.

The railway track structure parameters used are presented in the table below.

The curves in Fig. 2 illustrate the time responses of the displacement field and velocity of the railway track with a shock-absorbing mat, compared with experimental data and the studies carried out by Li Wang et al.39. The results obtained from the proposed analytical model are also analyzed and validated based on the previous results in the literature.

The observed differences must come from the applied boundary and initial conditions. In addition, the results presented show high amplitude at the beginning but which decrease over the time and tend to cancel out. In this section, our results are presented with the 20 Hz frequency of harmonic load.

Behaviour of railway superstructure components

For this study, two cases are considered. The linear and the non-linear cases. Nonlinear behavior appears in Eq. (38): it is characterized by the fourth derivative of the displacement \(w\left( {x,t} \right)\) with respect to the spatial variable \(x\). This derivative comes from the mathematical modeling in Eq. (1) which takes into account the product of the flexural rigidity of the rail by a derivative of order four of the displacement \(w\left( {x,t} \right)\).Therefore, linear and non-linear cases referred to the flexural rigidity of the rail and fourth derivative of displacement \(w\left( {x,t} \right)\), the term: \(E_{R} I_{R} w_{R}^{\left( 4 \right)}\). The problem is considered as linear when the mentioned term is neglected and as nonlinear when this term is taking into account for the resolution.

Rail behaviour: linear and nonlinear case

Figure 3 presents rail time response curves of displacement, velocity and acceleration for the track without and with a shock-absorbing mat insert between the sleepers and the ballast, this for linear and non-linear cases respectively.

The red curves in Fig. 3a-b show a real attenuation of the amplitude of rail displacement on the track with the rubber mat. Indeed, for a harmonic load applied on the top of both railway track models, the maximum amplitudes of displacement are estimated at 1.423 × 10−3 m for the track without a shock-absorbing mat and 5 × 104 m for a track with a shock-absorbing mat for the linear case. For this case, the decrease in amplitude is evaluated at 64.9%. In the nonlinear case where the nonlinearity appears with the flexural rigidity of the rail, the decrease in amplitude is evaluated at 94%.

The curves in Fig. 3c-f also show a rapid decrease in the amplitude of velocity and acceleration respectively. These significant attenuation of displacement, velocity and acceleration amplitudes leeds to the stability of rail and highlight the effect of the rubber mat in the railway track. With a shock-absorbing mat in the railway track, the train pitching will significantly reduce. The nonlinearity appears with the flexural rigidity of rail.

Sleeper’s behaviour: linear and nonlinear case

The curves in Fig. 4 show the influence of the rubber mat on the dynamic behavior of the sleepers under which a shock-absorbing mat is placed.

Figure 4a-b show that the responses of the sleepers to rail excitation on the railway track model with the rubber mat for linear case is evaluated at 5.4 × 10−4 m and 0.7 × 10−4 m for nonlinear case. On the conventional railway track model without a rubber mat, the maximum amplitudes are respectively 4 × 10−3 m for linear case, and 1.6 × 10−4 m for nonlinear case. For the sleepers, it appears that the vibration amplitudes are attenuated by 86.5% et 56.25% respectively for linear and nonlinear cases. This attenuation highlights the influence of the shock-absorbing mat on the reduction and the transmission of transverse vibrations from the sleepers to the ballast layer.

Figure 4c-f present the effects of using a rubber mat on the displacement and the velocity of sleeper’s movement. As a result, the sleeper velocity amplitudes on the track with a shock-absorbing mat imply very slow movement, and ensure the stability of these sleepers as well as the stability of the track during train passage.

Ground behaviour: linear and nonlinear case

The curves in Fig. 5 present the variations of the displacement, the velocity and the acceleration at the ballast lower side and the ground surface.

On Fig. 5a-b, it emerges once again that the rubber mat provides cushioning of the amplitudes of movements at ground level. This highlights the hypothesis that the vibrations induced by the passage of the train have less impact on the ballast and the ground surface in railway track model with a shock-absorbing mat. Indeed, for the linear case the attenuation is evaluated at 53% and at 6.85% for the nonlinear case. In fact, vibrations induced in the railway track during the passage of trains will be transmitted to the neighboring environment and the nearby structures after attenuation.

On Fig. 5c-f respectively, the curves of velocity and acceleration for both models emphasize the rapid decrease in amplitudes and the very slow displacement of the ground surface in the railway track with rubber mat. This phenomenon confirms that the vibrations transmitted in the vicinity of this railway track model are very low on amplitude.

Stress variation

Influence of the rubber mat thickness and ground depth on the stress value

The curves in Fig. 6 represented on the railway length mentioned in Table1, illustrate the variation in stress at ground surface (z = 0) and at the ground depth (z = 0, 3 m).

Variation of stress with the rubber mat thickness and ground depth on railway length in Table 1.

Figure 6a shows that, at the ground surface, the stress decreases with the increase of the shock-absorbing mat thickness. Indeed, when the shock-absorbing thickness varies from zero to 0, 06 m, the stress decreases from 10.84 MPa to 9.866 MPa. Figure 6b emphasizes the decrease of stress values with the rubber mat thickness and with the depth of the ground. The expression of the stress given by Eq. (30) depends on the position \(x\) of the load on the railway track and the depth \(z\) of the ground layer. The figures obtained show that the stress is symmetrical with respect to the origin of the railway track where the maximum value is obtained.

Influence of the Young’s modulus of the soil on the stress

To emphasize the influence of the type of soil on the stress value at the ground surface, the stresses given by Eqs. (36) and (37) are represented on the below figures. Mechanical characteristics of different type of soils used as support for the railway track are presented in Table 2.

Equations (36) and (37) show that stress depends on young modulus and Poisson ratio. Indeed, according to Table 2, the stress increases with the Young’s modulus of the considered soil. Figure 7a, 7-b, 7-c and 7-d prove that, the stress value increase with the Young’s modulus. For a track portion of length 80 m, as mentioned in Table 1 and symmetrical with respect to zero, the stress is also symmetrical with his maximum at this point.

(a–d) Evolution of stress with Young’s modulus of the ground presented in Table 2.

Scalar potential variation along the length

Figure 8 represents the behavior of the scalar potential along the track length for different values of the rubber mat thickness. We observed that the rubber mat layer is an essential component in the modeling of a railway track for its ability to reduce and attenuate vibrations. The sinusoidal shape of the curve along the railway length, justifies the fact that train locomotive generates a harmonic movement as it passes which induces vibrations in the railway track and on the surface of the surrounding ground.

Effect of excitation on the rail, sleeper and ground

The curves in Fig. 9 illustrate the effect of the excitation force on the displacements of the rail, the sleepers and the ground for the railway track without and with a shock-absorbing mat at the sleepers- ballast interface. This study highlights the effect of overloading on the railway track. Indeed, the amplitudes of vibrations in the railway track structure and at ground surface increase with the strength value. High amplitudes of vibration on the ground surface led to instability of the railway track, the supporting ground as well as the structures built in the vicinity of the railway track during the passage of trains.

This study also shows the importance of rubber mat in vibration attenuation in the railway track structure and the surrounding ground and structures. On Figs. 9a, and 9-b, 9-c and 9-d, 9-e and 9-f, we respectively represent rail displacements, sleeper’s displacements and ground-ballast interface displacements for both models of railway track. We observed a significant attenuation of vibration amplitudes in the track model with damping mat at the sleepers-ballast interface (Fig. 10).

The influence of a harmonic load written as \(F = F_{B} e^{i \, \Omega t}\) on the displacement’s amplitudes of the rail, the sleepers and the ground by varying the excitation frequency \(\Omega\) of the load is also studied (Fig. 11).

From this study, it appears that the amplitudes of displacements decrease when the excitation frequency increases. Whatever the frequency, the amplitudes of displacements on the track with a shock-absorbing mat remain lower than those of the conventional track without rubber mat layer (Fig. 12).

For each frequency, the maximum vibration amplitude on the track without a shock-absorbing mat is greater than that on the railway track with a shock-absorbing mat. For the sleepers for example, maximum displacement amplitudes for the three frequencies are evaluated approximately at 1.4 × 10−3 m for the track without rubber mat and about 1 × 10−3 m for the track with rubber mat. The different results obtained are in agreement with expectations on the model and with the first results.

Conclusion

Rail transport is of capital importance today in the world and especially in African countries. The search for solutions to improve its performances became a serious problem to solve for railway engineers, railway companies and even countries. In this work, we presented a non-linear modeling of a railway track with the ability to attenuate the effects of vibrations induced in the track and in the supporting ground as well as nearby structures. The proposed railway track model integrates a damping mat at the sleeper-ballast interface. The Newmark numerical method was used to represent the displacements, velocity and accelerations of the track components as well as the ground. From this study, we noted that the configuration of the railway track with a shock-absorbing mat significantly reduces the amplitudes of vibration in the track and in the surrounding ground. Indeed, the comparison of the results obtained with the two railway track models shows the reduction in vibration amplitudes of 64.9% and 94% for the rail, 86.5% and 56.25% for the sleepers and 53% and 6.85% at the ground surface, respectively for linear and nonlinear cases. Besides displacements, the insertion of the damping mat into the structure of the track also allows the decrease of the stress with the shock-absorbing mat thickness, the reduction of the accelerations of the different component, and also the speeds of movement. The configuration of the railway track with a damping mat therefore reduces the amplitudes of vibration transmitted to the ground and to the nearby structures. Indeed, the shock-absorbing mat at the sleepers-ballast interface contributes to the stability of the track and the improvement of its performance.

Data availability

All the data used to obtain the results of this study are included in the article.

Abbreviations

- 2b :

-

Sleeper/ground width of contact

- c :

-

Load speed

- RL :

-

Rubber layer

- m R :

-

Mass per unit length of rail

- m S :

-

Mass per unit length of sleeper

- m B :

-

Mass per unit length of ballast

- w R :

-

Rail displacement

- w B :

-

Ballast displacement

- F S (x 1,t):

-

The strength transmitted by the track to sleepers

- F B (x 1,t):

-

The strength transmitted by the ballast to the ground

- H (x,t):

-

Restoring force induced by the sock-absorbing mat

- k p :

-

Sleeper stiffness

- K B :

-

Ballast stiffness

- λ, µ :

-

Lamé constants

- \(\dot{w}_{R}\) :

-

Rail velocity

- \(\dot{w}_{S}\) :

-

Sleepers’ velocity

- \(\dot{w}_{B}\) :

-

Ballast velocity

- \(\ddot{w}_{R}\) :

-

Rail acceleration

- \(\ddot{w}_{S}\) :

-

Sleeper acceleration

- \(\ddot{w}_{B}\) :

-

Ballast acceleration

- w S :

-

Sleeper displacement

- k E :

-

Rubber mat stiffness

- \(\eta_{p}\) :

-

Sleeper damping coefficient

- \(\eta_{E}\) :

-

Rubber mat damping coefficient

- \(\lambda , \, \mu \,\) :

-

Lamé constants

References

Thompson, D. J., Kouroussis, G. & Ntotsios, E. Modelling, simulation and evaluation of ground vibration caused by rail vehicles. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 57(7), 936–983 (2019).

Sheng, X. A review on modelling ground vibrations generated by under ground trains. Int J. Rail Transp. 7(4), 241–261 (2019).

Connolly, D. P., Marecki, G. P., Kouroussis, G., Thalassinakas, I. & Woodwark, P. K. The growth of railway ground vibration problems-a review. Sci. Total Environ. 568, 1276–1282 (2016).

Zhang, X., Zhou, S., Di Hec, H. & Si, J. Experimental investigation on train-induced vibration of the ground railway embankment and under-crossing subway tunnels. Transp Geotech 26, 100422 (2021).

Krylov, V. Effect of track properties on ground vibrations generated by high speed-trains. Acustica-Acta Acustica 84(1), 78–90 (1998).

Jones, C. J. C. & Block, J. R. prediction of ground vibration from freight trains. J. Sound Vib. 193(1), 205–213 (1996).

Krylov, V. & Ferguson, C. Calculation of low frequency ground vibrations from railway trains. Appl. Acoust. 42(3), 199–213 (1994).

Jayasuriya, C., Indraratna, B. & Ferreira, F. B. The use of under sleeper pads to improve the performance of rail tracks. Indian Geotech. J. 50(2), 204–212 (2020).

Ngamkhanong, C. & Kaewunruen, S. Effects of under sleeper pads on dynamic responses of railway prestressed concrete sleepers subjected to high intensity impact loads. Eng. Struct. 214, 110604 (2020).

Nimbalkar, S., Indraratna, B., Dash, S. K. & Christie, D. Improved performance of railway ballast under impact loads using Shock Mats. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 138(3), 281–294 (2012).

Branson, J. M., Dersh, M. S. S., Lima, A. D. O. O., Edwards, J. R. & Cesar, B. J. Identification of the under-tie pad material characteristics for stress state reduction. J. Rail Rap. Transit 234(10), 1227–1237 (2020).

Indraratna, B., Ngo, N. T. & Rujikiatkamjorn, C. Improved performance of ballasted rail tracks using plastics and rubber inclusions. Proceedia Eng. 189, 207–214 (2017).

Ngo, N. T., Indraratna, B. & Rujikiatkamjorn, C. Stabilization of track substructure with geo-inclusions-experimental evidence and DEM simulation. Int. J. Rail Transp. 6, 35 (2017).

Schneider, P., Bolmsvik, R. & Nielsen, J. C. O. In Situ performance of a ballasted railway track with under sleeper pads. J. Rail Rap. Transit. 225, 630 (2015).

Ribeiro, C. A., Paixao, A., Fortuna, E. & Calçada, R. Under sleeper pads in transition zones at railway underpasses: Numerical modelling and experimental validation. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 5, 26. https://doi.org/10.1080/15732479.2014.970203 (2014).

Kraikiewicz, C., Zbiciak, A., Oleksiewicz, W. & Pitrowski, A. The influence of selected static and dynamic parameters of resilient mats on vibration reduction of railways tracks. MATEC Web Conf. 219, 5002 (2018).

Johanson, A., Jens, C. O., Bolmsvik, N. R., Karlstrom, A. & Lunden, R. Under Sleeper Pads-Influence on Dynamic Train-Track Interaction (Elsevier, 2008).

Lakusic, S., Ahac, M. & Haladin, I. Experimental investigation of railway track with under sleeper pad. Slovenski Kongres O Cestah 5, 20–22 (2010).

Kaewunruen, S., Aikawa, A. & Remennikov, A. M. Vibration attenuation at rail joints through under sleeper pads. Transp. Geotech. Geoecol. 189, 193–198 (2017).

Ribeiro, A., Paixao, C., Fortunato, A. & Calçada, R. Under sleeper pads in transition zones at railway underpasses: numerical and experimental validation. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 11(11), 1432–1449 (2015).

Li, H. & Mc Donell, G. R. Discrete element modelling of under sleeper pads using a box test. Granular Matter https://doi.org/10.1007/s10035-018-0795-0 (2018).

Insa, R., Salvador, P., Inarejos, J. & Roda, A. Analysis of the influence of under sleeper pads on the railway vehicle/track dynamic interaction in transition zones. Proc. IMech E Part F 226(4), 409–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/0954409711430174 (2011).

Costa, P. A., Calçada, R. & Cardoso, A. S. Track-ground vibrations induced by railway traffic: In situ measurements and validation of a 2.5D FEM-BEM model. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 32, 111–128 (2012).

François, S., Schevenels, M., Galvin, P., Lombert, G. & Degrande, G. A 2.5D coupled FE-BE methodology for dynamic interaction between longitudinally invariant structures and layered half-space. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg 199, 1536–1548 (2010).

Yang, Y.-B. & Hung, H.-H. A 2.5D finite /infinite element approach for modelling visco-elastic bodies subjected to moving loads. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng 51, 1317–1336. https://doi.org/10.1002/nme.208 (2001).

François, S., Schevenels, M., Degrande, G., Borgions, J. & Thyssen, B. A 2.5D finite element-boundary element model for vibration isolating screens. Proc. ISMA. 5, 630 (2008).

Picoux, B. Etude théorique et expérimentale de la propagation dans le sol des vibrations émises par le trafic ferroviaire. Thèse de doctorat, Ecole centrale de Nantes (2002).

Vu Hieu, N. Comportement dynamique de structures non-linéaires soumises à des charges mobiles. Thèse de doctorat 1–179 (2002).

Picoux, B., Regoin, R. J. P. & Le Houédec, D. Prediction and measurements of vibrations from a railway track laying on a peaty ground. J. Sound Vibr. 267, 575–589 (2003).

Picoux, B. & Le Houédec, D. Diagnosis and prediction of vibration from railway trains. Soil Dynam. Earthqu. Eng. 25, 905–921 (2005).

Sheng, C. J. C. & Jones, M. P. Ground vibration generated by a harmonic Load acting on a railway track. J. Sound Vib. 225(1), 3–28 (1999).

Sheng, C. J. C. & Jones, M. P. Ground vibration generated by a Load Moving along a railway track. J. Sound Vib. 228(1), 129–156 (1999).

Lefeuve-Mesgouez, G. & Le Houédec, D. Ground vibration in the vicinity of a high-speed moving harmonic strip loads. J. Sound Vib. 231(5), 1289–1309 (2005).

Jones, D., Le Houédec, D., Peplow, A. T. & Petyt, M. Ground vibration in the vicinity of a moving harmonic rectangular load on a half-space. Eur. J. Mech. Solids 17, 536 (1998).

Jones, D. & Petyt, M. ‘Ground vibration in the vicinity of a strip load: an elastic layer on a rigid foundation. J. Sound Vib. 152(3), 501–515 (1992).

Jones, D. & Petyt, M. Ground vibration in the vicinity of a strip load: two-dimensional half-space model. J. Sound Vib. 147(1), 155–166 (1991).

Jones, D. & Petyt, M. Ground vibration in the vicinity of a rectangular load on a half –space. J. Sound Vib. 166, 141–159 (1993).

Thierry, L. Méthode de résolution des équations aux dérivées partielles (EDP) par séparation de variables; applications. Université de Lorraine, Année 2015–2016.

Wang, Li., Wang, P., Wei, K. & Dollevoet, R. Ground vibration induced by high-speed trains on an embankment with pile-board foundation: Modelling and validation with in situ tests. Transp. Geotech. 34, 100734 (2022).

Amodio, P. & Brugnano, L. Parallel implementation of block boundary value methods for ODEs. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 78, 197–211 (1997).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C.A. and CH. AD wrote the main manuscript text. M.C.A. prepared Fig. 1 CH.AD. prepared Figs. 2–5 R.P.L prepared Figs. 6–9 N.G.ED and S.CH made the first corrections All authors reviewed the final manuscript. All the authors have consented to publish our manuscript in Scientific Reports Journal.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moubeke, C.A., Chanceu, A., Sanga, R.P.L. et al. Modeling of railway track integrating a shock-absorbing mat at the sleepers-ballast interface using eigenfunctions of displacement. Sci Rep 14, 24783 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71906-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71906-1