Abstract

Integrating gender-affirming care with biomedical HIV prevention could help address the disproportionate HIV risk experienced by transgender and nonbinary (trans) adults. This discrete choice experiment assesses and identifies the most important programming factors influencing the decisions of trans adults to use injectable long-acting HIV pre-exposure prophylaxes (LA-PrEP). From March to April 2023 n = 366 trans adults in Washington state chose between four different choice profiles that presented hypothetical programs (each comprised of 5 attributes with 4 levels). We analyzed ranked choice responses using a mixed rank-ordered logit model for main effects. Respondents preferred to receive LA-PrEP from a gender-affirming care provider and a co-prescription for both oral and injectable hormones. Trans adults strongly favored 12-month protection and injection in the upper arm. No strong preferences emerged surrounding the type of health facility offering the gender-affirming LA-PrEP program. Our findings show that integrating and leveraging gender-affirming health systems, inclusive of medical services such as hormone therapy, with HIV biomedical products like LA-PrEP is strongly preferred and influential to trans adults’ decision to use LA-PrEP. Leveraging choice-based design experiments provides informative results for optimizing gender-affirming LA-PrEP programming tailored to trans adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transgender and nonbinary (trans) adults represent 1.4 million adults in the United States (US) and experience disproportionate risk for HIV acquisition and poor HIV-related care outcomes1,2. While the overall HIV prevalence in the US general population is less than 0.5%, it is concentrated and reported to be 14.1% among trans women and 3.2% among trans men in the US2. By race/ethnicity, HIV prevalence is estimated to be 44% in Black trans women and 26% in Latina trans women2. This high HIV prevalence is compounded by the high proportion of undiagnosed HIV infection (i.e., > 20%) in this population3. Informed by this epidemiology, researchers have called for gender-inclusive intervention approaches that enable the delivery of HIV prevention tools while recognizing and supporting the health needs and gender goals of trans people4,5,6.

Recently, substantial scientific progress has been made in the development, testing, and approval of new modalities for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxes (PrEP), including long-acting injectables (LA-PrEP)7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14—which hold enormous potential to avert new HIV infections among trans adults. The CDC has identified trans people as a key population for PrEP, and encourages healthcare providers to discuss PrEP with trans patients as one of the key options for HIV prevention15. However, PrEP uptake is persistently low among trans individuals; among more than 1600 HIV-negative transgender women who responded to the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance survey, PrEP utilization rates were 35% in 2017 and 32% in 202116. While reasons behind the low PrEP uptake among trans individuals include social and structural barriers such as gender-based stigma, lack of trust in healthcare providers, being susceptible to socio-economic vulnerabilities (e.g., unemployment, uninsured), and avoiding stigmatizing healthcare systems, there is limited evidence on strategies that effectively enhance PrEP uptake in this specific population.

Behavioral insights into how individuals make decisions about their HIV prevention behaviors can guide effective intervention design and implementation17,18. In many contexts, especially resource-limited settings, subsidies or financial incentives are used to overcome the economic and logistical barriers that threaten uptake of and adherence to HIV prevention services19,20,21. However non-financial nudges are also effective, and potentially more cost-effective, for HIV prevention20. Nudges based on “convenience”, “user-centeredness”, and “choice architecture” aim to structure options in a way that makes positive health decisions easy, attractive, social, and timely for the end user22,23. For the choice architecture of an HIV prevention program to meet these criteria, we must first understand what matters most to the program’s target participants.

Discrete choice experiments (DCEs) offer one systematic way of measuring users’ preferences. Stemming from marketing science, DCEs have become increasingly utilized in the fields of health economics and health psychology to understand individual and institutional preferences for health interventions24, including for HIV prevention25,26. Systematic reviews of DCEs eliciting preferences for PrEP cite dosing frequency, cost, drug effectiveness, and side effects to be some of the most important attributes influencing decisions around PrEP uptake and adherence25,26. To the best of our knowledge, however, none of these PrEP-focused DCEs have been administered to trans populations, or included attributes relevant to the gender-affirming care needs of this population. Actual uptake of LA-PrEP among trans populations is more likely to improve and sustain over time if we first uncover and quantify the stated preferences of trans adults. Understating these preferences can nudge trans populations to engage in programs that are user-centered and user-informed, thereby maximizing LA-PrEP adherence. In this analysis we aimed to quantify trans adults’ relative preferences for injectable LA-PrEP protection duration, provider type, service location, and hormone co-prescription type offered as part of a hypothetical gender-affirming, HIV prevention program.

Methods

The discrete choice experiment (DCE) described in this paper was nested within a larger web-based survey conducted by the Washington Priority Assessment in Trans Health (PATH) Project, a community-informed statewide cross-section needs assessment study developed for, by, and with trans communities in Washington State. The exploratory DCE was conducted from a patient or client perspective, and aimed to answer the research question of “What clinical and programmatic components matter most to trans adults who may be eligible for a LA-PrEP and gender-affirming care program?”

Attributes and levels

The attributes and levels for use in the DCE were selected by study investigators based on a review of the literature and reiterative consultations with the study’s all-trans Transgender Scientist and Stakeholder Advisory Board (TSSAB). The TSSAB, which is comprised of transgender and nonbinary scholars, leaders, and community members in Washington, was purposefully assembled to guide and review the study procedures, materials, and content, including deciding which attributes and levels are most relevant to test. Specifically, after conducting a brief review of the literature, consultations with TSSAB members were conducted reiteratively prior to survey administration to narrow the most salient attribute and possible levels that are based on realistic contexts of delivering PrEP within the Washington healthcare system. During consultations, other possible attributes and levels were also considered. Cost/affordability and support services were originally considered, but ultimately, the TSSAB decided not to include them as both attributes did not fit the study’s main purpose, which is centered on incentivizing PrEP uptake through promoting it as a free, readily available, and accessible product.

The final discrete choice experiment consisted of five attributes that contained four levels each inclusive of an opt out option (Table 1). Attributes included: “location” of LA-PrEP injection (with levels of Upper arm, Thigh, Gluteal, or No injection (opt-out)); “duration” of LA-PrEP protection against HIV infection (with levels of 12 months, 6 months, 2 months, or 0 months (opt-out)); “provider type” for administering LA-PrEP (with levels of HIV care provider, Primary care provider, Gender-affirming care provider, or No provider (opt-out)); “site” where LA-PrEP program is offered (HIV care clinic, Primary care clinic, Gender-affirming care clinic, or No site (opt-out)); and type of gender-affirming “hormone” delivered at LA-PrEP appointment (Injectable and oral hormone co-prescription, Injectable hormone co-prescription, Oral hormone co-prescription, or No co-prescription (opt-out)).

Concerning the levels for the duration attribute, we included levels that reflect the duration of protection from LA-PrEP that is currently available on the market, as well as aspirational protection durations. Specifically, the 2-month duration of protection level reflects long-acting cabotegravir (CAB-LA), which is an intramuscular injectable, long-acting form, with the first 2 injections administered 4 weeks apart, followed thereafter by an injection every 8 weeks27. The 6-month duration of protection level reflects Gilead Sciences’ long-acting capsid inhibitor, lenacapavir (sold as Sunlenca), which is administered by subcutaneous injection every six months28. Lenacapavir is already approved for treatment-experienced people with multidrug-resistant HIV and it is being evaluated as a twice-yearly PrEP option28. The 12-month duration of protection level was included by the TSSAB as an aspirational level to assist with more clearly understanding how strongly longer protection duration was preferred over other levels of this attribute, and over other attributes.

Choice tasks and experimental design

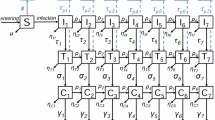

We developed 40 choice tasks and blocked them into 4 survey versions with 10 choice tasks for each. Each block represented a separated survey, and participants were randomly assigned to one of the four survey versions and to respond to 10 program comparisons. For each program comparison, or “choice set”, respondents were asked to choose between different choice profiles that presented hypothetical programs (Supplementary Fig. 1). Hypothetical programs provided a combination of LA-PrEP and gender-affirming services every two months. Four choice profiles (each comprised of 5 attributes with 4 levels) were combined to form a choice set such that for each choice set respondents chose from random combinations of: Program A, Program B, Program C, or No Program. Each profile presented all attributes and levels being considered in the study (a full profile). We chose to include an opt-out (No Program) option for each choice task because having the option to abstain from an elective program is reflective of a respondent’s real-life choices, and opt-out options have shown to perform well in statistical analyses29,30. The design follows recommendations from the literature that respondents can reasonably respond to 9–16 choice sets with 4–6 attributes before reaching cognitive overload31,32. We used a best-best elicitation method33,34 where respondents were first asked to select their first choice from the 4 choice profiles (Program A, Program B, Program C, or No Program), and to then select their second-best option from the remaining 3 profiles.

Administering a full factorial design (i.e., S = 45 = 1024 possible scenarios) was not possible without placing an undue burden on participants. To narrow the number of choice options while ensuring statistical efficiency, we implemented a blocked D-efficient partial factorial design using the Stata SE (College Station, TX, version 17) dcreate procedure35, which maximizes design efficiency based on the covariance matrix of the conditional logit model36. The variance–covariance matrix of the β coefficients assumed zero priors and two potential interactions (between duration of protection and injection site, and between provider type and hormone co-prescription type).

We calculated our minimum required sample size as N > (500c)/(t × a), where t is the number of choice sets, a is the number of alternatives per set, and c is the largest number of levels for any one attribute32. Thus, our minimum required sample size was N > (500 × 4)/(10 × 4) = 50. We enrolled considerably more respondents to allow further analysis with covariates and interactions, with a final sample size of N = 366.

Preference elicitation and data collection

The parent PATH study used convenience sampling to recruit participants, which included reaching out to local organizations, community listservs, social media platforms, trans-focused support groups, and events. To be eligible, individuals had to be 18 years or older, identify as transgender and/or nonbinary, currently live in Washington State, and be willing and able to provide electronic consent to participate in the study. Once screened for eligibility and enrolled, participants were directed to the web-based survey, which was designed to be user-friendly (e.g., simple design and wording, preventing multiple responses, allowing for saving and finishing later). The survey captured participants’ demographic information, and healthcare experiences and needs, alongside the discrete choice experiment (DCE) that surveyed LA-PrEP programming preferences. The entire survey was piloted to take less than 25 min to complete, with the DCE portion taking approximately 10-min to complete.

Data collection occurred from March to April of 2023. All research procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division (IRB #:STUDY00015878) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Statistical analyses

We first used a conditional logit regression to explore patients’ primary (first) choice of a hypothetical program. In a conditional logit, the probability of choosing among at least two alternatives is related to the attribute levels characterizing the alternatives37,38. The dependent variable was the participants’ first preferred program in each choice task and the independent variables were the dummy-coded levels of each of the attributes in each profile. Dummy coding estimates the preference weights of a given attribute level relative to the omitted level of that attribute37,38.

To assess main effects, we then used the best-best approach with an ‘exploded logit’ by expanding the data from each choice set into two choice subsets. The best-best approach elicits a respondent’s first-best choice of all hypothetical programs and then asks for their second-best choice from the remaining alternatives39. Compared to a traditional best–worst DCE design, the best-best approach has shown to improve efficiency of data collection (by eliciting additional observations per choice and reducing respondent burden with fewer choice sets) as well as statistical efficiency34. The first subset contained four rows of data representing the four alternatives in the original set where the dependent variable (choice) = 1 for the first-best and = 0 for the remaining alternatives. The second subset identified the second-best from the remaining three alternatives39,40. We analyzed the ranked choice responses using a mixed rank-ordered logit (MROL) model, which included normally distributed random parameters to allow for unobserved heterogeneity in latent preferences for a chosen Program compared with No Program. We included a constant term; age, gender, race, highest education completed, income before taxes last year, and geography of current residence were modelled as continuous or categorical variables; other attributes (has ever taken PrEP, has ever engaged in sex work) were dummy coded. Specifications of the MROL model are included in the supplementary material.

The MROL model showed the best performance based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC) values, and exploited more of the available data, and thus was used to assess main results. We used a rank ordered logit (ROL) model and a generalized multinomial logit model (GMNL), additionally, to check for robustness of main results. Lastly, to explore preference heterogeneity, we looked at the average program choice probabilities over the entire range of participant ages, income, and education levels.

Results

Respondent characteristics

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the 366 trans participants who completed the DCE. Respondents were 29 years of age on average (IQR: 26–32 years, not shown). Most were women (79.8%), White (64.2%), lived in or near a large city (59.6%), had health insurance (99.5%), and reported completing 1–3 years of college or less (88.8%). Only 16.4% (i.e., sixty participants) reported having ever previously taken PrEP for HIV prevention.

Attribute and program preferences

Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1 show preference weights for the five attributes based on the primary (first) choice from the conditional logit regression model. Survey respondents preferred receiving LA-PrEP from a gender-affirming care provider (rather than an HIV provider or primary care physician), and preferred receiving a co-prescription for oral and injectable gender-affirming hormones (rather than solely oral or injectable) at their LA-PrEP visit. Respondents strongly preferred LA-PrEP that provided protection against HIV for up to 12 months, and being administered the LA-PrEP injection in their upper arm (rather than in the glutes or thigh). There was no strong preference as to the type of site that should offer the gender-affirming LA-PrEP program. As shown in Table 3, when normalized to the scale of 100%, the duration of LA-PrEP protection had the highest relative attribute importance (37.1%), followed by injection site on the body where LA-PrEP is administered (21.4%) and type of provider administering LA-PrEP (19.9%). The type of health facility offering the LA-PrEP program had the lowest relative importance (3.2%).

Mean preference weights with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Bars represents mean preference weights and error bars present 95% confidence intervals. Estimates are from conditional logistic regression models that included the primary (first) program choice vs all other program choices as the dependent variable and dummy-coded variables for each attribute level as the independent variables. Dummy coding estimates the preference weights of a given attribute level relative to the omitted level of that attribute. A more positive weight indicates a stronger preference towards a given attribute level.

Table 4 shows results from the MROL model using the complete ranking data coming from the best–best choices of DCE respondents. In terms of alternative-specific variables, the coefficient on the 12-month duration of LA-PrEP protection is positive (β = 0.127) and strongly significant (p < 0.001), indicating that the probability of choosing a hypothetical program increases as the length of LA-PrEP protection against HIV increases. Similarly, the coefficients on LA-PrEP being administered in the upper arm (β = 0.073), on LA-PrEP being administered by a gender-affirming provider (β = 0.087), and LA-PrEP visits also providing a co-prescription for oral and injectable hormones (β = 0.10) are also positive and statistically significant (p < 0.05). Although not statistically significant, the coefficients for the program site attribute levels suggest that trans adults may prefer to attend a gender-affirming LA-PrEP program at a gender clinic rather than at an HIV clinic or primary care facility. The standard deviations (column 2) are large relative to the means of the associated attribute coefficients (column 1), which indicates there is heterogeneity in preferences across respondents. Supplementary Table 2 shows the results of the rank ordered logit and generalized multinomial logit models, which show generally consistent trends as the MROL model for the relevant alternative-specific coefficients.

Figure 2 shows the averaged choice probabilities over the entire age range of DCE respondents. Among individuals between 18 and 35 years of age, all three hypothetical programs have a 5 – 25 percentage-point higher probability of being chosen than the opt-out option, depending on age and program. After the age of 50, the average probability of choosing the opt-out option (i.e., no program) is higher than the probability of choosing any hypothetical program. No clear trend in program choice probability was seen over the range of possible annual income; and the probability of choosing a hypothetical program over no program did not seem to vary by education level (Supplementary Fig. 3a and b).

Average choiced probabilities over the entire age range. The figure presents the averaged choice probabilities over the entire age range, excluding all other case-specific variables from the rank order logit model. Among individuals between 18 and 35 years of age, all three hypothetical programs have a 5–25% higher probability of being chosen than the opt-out option, depending on age and program type. For participants 50 years and older, the averaged probability of choosing the opt out option is higher than the probability of choosing any hypothetical program.

Robustness tests

Estimates from additional models are presented in Supplementary Table 2. First, in columns (1–4) is the ROL model, which shows similar results as the main model. Column (5) is the GMNL, which also shows similar results as the MROL except for site of LA-PrEP delivery being HIV clinic or gender clinic, which are both positive and significant (p < 0.01). The τ parameter for the GMNL was significant, which indicates unobserved heterogeneity.

Supplementary Table 3 presents the correlation matrix used to check for orthogonality. The pairwise correlation coefficients are generally low, which provides evidence that each relevant attribute level and covariate vary independently of one another.

Discussion

The findings from this study provide valuable insights into the attributes and program preferences of trans adults regarding LA-PrEP for HIV prevention. The results indicate that trans adults overwhelmingly prefer to receive LA-PrEP within a gender-affirming healthcare approach41– that is, situating LA-PrEP continuum services within a health system that also recognizes and ensures trans adults’ gender goals are medically, socially, and structurally supported42,43. The directions of the findings support what most researchers have persistently emphasized when designing gender-affirmative public health programming for, by, and with trans communities44,45. We further add empirical evidence, by using a DCE design for health programming, so that researchers and program planners can identify and optimize specific attributes and program features that are influential and deemed most important among transgender adults. Making the programs and services more convenient and responsive to the users’ preferences and needs is a crucial tenet of the behavioral economics’ “choice architecture” concept46.

We found that respondents showed a strong preference for receiving LA-PrEP from a gender-affirming care provider rather than an HIV provider or primary care physician, and that the type of health facility offering the gender-affirming LA-PrEP program did not significantly influence preferences (under two of the three main specifications). These findings underscore two important implications for LA-PrEP programming: First, it highlights the importance of culturally competent gender-affirming healthcare systems and the need for providers who are knowledgeable about trans patients’ health needs. Given that trans individuals often face unique healthcare challenges (e.g., being denied health insurance coverage) and avoid healthcare visits due to past negative experiences (e.g., experiencing mistreatment and/or being stigmatized from providers and staff)47,48,49, having providers who understand and respect trans people’s gender identity can greatly enhance their overall healthcare experience. Second, while gender-affirming care providers are likely more adept to providing such an approach to care compared to HIV providers or primary care physicians (and therefore most preferred by trans adults), the results also indicate that trans adults are open to accessing these services in any type of healthcare settings, as long as the care is affirming and meets their specific needs. These two findings, therefore, highlight the importance of situating LA-PrEP in healthcare environments that are welcoming and inclusive with providers that practice gender-affirming approaches to care, regardless of the specific type of facility. Healthcare providers and public health professionals, PrEP programmers, and policymakers should work towards ensuring that gender-affirming care is available and accessible across different healthcare settings when scaling up LA-PrEP.

Additionally, we also found that trans adults prefer having a co-prescription for both oral and injectable gender-affirming hormones during the LA-PrEP visit, highlighting the desire for comprehensive and integrated healthcare services, particularly between HIV prevention and gender-affirming medical care. While gender-affirming hormone therapy is a priority for many trans populations, understanding ways to address trans people’s concerns and/or misinformation regarding adverse side effects or drug interactions of PrEP with co-prescribed medicines like hormones via an intervention is vital to increasing PrEP uptake and its programming50,51,52. To combat misinformation, for example, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends delivering evidence-based messaging given that there are no known or predicted drug interactions between the medications used for PrEP and gender-affirming hormones53. This finding suggests that trans individuals value the convenience and holistic approach of receiving multiple aspects of their care in a single visit, which is similar to what other studies calling for multilevel component intervention design have noted previously41,54,55. By combining LA-PrEP with gender-affirming hormone therapy, healthcare providers can offer a more comprehensive and personalized approach to trans health, particularly meeting both HIV prevention needs and gender goals of trans individuals.

Respondents also expressed a strong preference for LA-PrEP that provides protection against HIV for up to 12 months. This longer duration of protection aligns with the desire for a simplified and less frequent dosing regimen56,57,58, which can enhance adherence and reduce the burden of medication management. Trans individuals may already have complex medication regimens, and having a longer-acting form of HIV prevention can alleviate some of the challenges associated with adherence to daily medication59,60. Moreover, the location of the LA-PrEP injection site was another important factor influencing preferences. Respondents favored receiving the injection in their upper arm rather than in the glutes or thigh. This preference may be driven by factors such as comfort, ease of self-administration, and potential visibility of injection sites56,57,58 Understanding these preferences can inform the development of administration techniques and training materials for healthcare providers to ensure that LA-PrEP injections are delivered in a manner that aligns with the preferences and needs of transgender individuals.

While this study provides valuable insights, it is not without limitations. The sample primarily consisted of trans adults from the state of Washington, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other geographical settings. Future research should aim to include a more diverse sample to capture a broader range of perspectives. Additionally, longitudinal studies can provide further insights into how preferences may change over time and in response to different biomedical products that are or will be in the pipeline. Moreover, this study focused on preferences for LA-PrEP attributes and programs. Future research could explore other factors that may influence decision-making, such as cost (including subsidies or incentives), accessibility, and side effects, which can also be identified and tested via a DCE design61,62,63,64,65. In terms of the experimental design, using a partial factorial design (as was done in this DCE) can make it difficult to distinguish interaction effects from main effects, which can lead to incorrect interpretation of findings if or when confounded effects are substantial. Also, deciding upon the second-best choice in a best-best preference elicitation design may be mentally difficult for respondents in some instances34. Lastly, while it is not a limitation of the study per se, it is important to note that there was heterogeneity in preferences across respondents, as indicated by the large standard deviations relative to the means of the attribute coefficients. While results are generally significant at the group level, this highlights the diversity within the trans population and the need for more research to identify within-group patterns to inform personalized approaches to care and service delivery. Healthcare providers should be mindful of this heterogeneity and strive to provide individualized care that takes into account the unique preferences and needs of each transgender individual.

Conclusion

Overall, these findings contribute to a better understanding of the preferences of trans adults regarding LA-PrEP for HIV prevention. The insights gained from this study can inform the development and implementation of gender-affirming healthcare programs and interventions aimed at improving HIV prevention and care outcomes among transgender individuals. By incorporating these preferences into program design and implementation, healthcare providers and policymakers can better meet the needs of transgender individuals and improve health outcomes in this population. Continued research and collaboration are needed to further contextualize how LA-PrEP fits into the lives and geographical contexts of trans adults and approaches to ensure equitable access to new HIV biomedical products for trans communities. The use of a behavioral economics general approach in conjunction with a DCE design can be a useful tool to identify and optimize ways to address the unique healthcare needs of trans individuals and to provide the affirming and comprehensive programming care this population deserves.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and approval from the University of Washington IRB.

References

Flores, A. R., Herman, J., Gates, G. J. & Brown, T. N. How Many Adults Identify as Transgender in the United States? Vol. 13 (Williams Institute, 2016).

Becasen, J. S., Denard, C. L., Mullins, M. M., Higa, D. H. & Sipe, T. A. Estimating the prevalence of HIV and sexual behaviors among the US Transgender population: A systematic review and meta-analysis, 2006–2017. Am. J. Public Health109, E1–E8. https://doi.org/10.2105/Ajph.2018.304727 (2019).

Schulden, J. D. et al. Rapid HIV testing in transgender communities by community-based organizations in three cities. Public Health Rep.123, 101–114 (2008).

Restar, A. J. (2023). Gender-affirming care is preventative care. The Lancet Regional Health–Americas, 24.

Scheim, A. I. & Travers, R. Barriers and facilitators to HIV and sexually transmitted infections testing for gay, bisexual, and other transgender men who have sex with men. AIDS Care29, 990–995 (2017).

Sevelius, J. “There’s no pamphlet for the kind of sex I have”: HIV-related risk factors and protective behaviors among transgender men who have sex with nontransgender men. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care20, 398–410 (2009).

Murray, M. et al. In Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 22–25.

Hope, T. J. & Marrazzo, J. M. A shot in the arm for HIV prevention? Recent successes and critical thresholds. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir.31, 1055–1059 (2015).

Schlesinger, E. et al. A tunable, biodegradable, thin-film polymer device as a long-acting implant delivering tenofovir alafenamide fumarate for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. Pharm. Res.33, 1649–1656 (2016).

Johnson, L. M. et al. Characterization of a reservoir-style implant for sustained release of tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Pharmaceutics11, 315 (2019).

Gatto, G. et al. In Proceedings of the Conference on Retrovirusus and Opportunistic Infections (CROI).

US Food and Drug Administration..Sunlenca/Lenacapavir Receives FDA Approval as a First-in-Class, Twice-Yearly Treatment Option for People Living With Multi-Drug Resistant HIV. (2022). Retrieved from Available at: https://www.gilead.com/news-and-press/press-room/press-releases/2022/12/sunlenca-lenacapavir-receives-fda-approval-as-a-firstinclass-twiceyearly-treatment-option-for-people-living-with-multidrug-resistant-hiv.

Landovitz, R. J. et al. Cabotegravir for HIV prevention in cisgender men and transgender women. N. Engl. J. Med.385, 595–608 (2021).

US Food Drug Administration (FDA). FDA approves first injectable treatment for HIV pre-exposure prevention. Updated December 2021. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-injectable-treatment-hiv-pre-exposure-prevention.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Testing, Prevention and Care for Transgender People. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/clinicians/transforming-health/health-care-providers/prevention-and-care-data.html (2021).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV infection, risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among transgender women—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 7 US cities, 2019–2020. HIV Surveill. Spec. Rep.27, 15 (2021).

Roy Paladhi, U., Katz, D. A., Farquhar, C. & Thirumurthy, H. Using behavioral economics to support PrEP adherence for HIV prevention. Curr. HIV AIDS Rep.19, 409–414 (2022).

Linnemayr, S. HIV prevention through the lens of behavioral economics (draft). J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr.68, e61 (2015).

Galarraga, O. & Sosa-Rubi, S. G. Conditional economic incentives to improve HIV prevention and treatment in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet HIV6, e705–e714. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30233-4 (2019).

Galárraga, O. et al. We must invest in behavioural economics for the HIV response. Nat. Hum. Behav.7, 1241–1244 (2023).

Celum, C. L. et al. Incentives conditioned on tenofovir levels to support PrEP adherence among young South African women: A randomized trial. J. Int. AIDS Soc.23, e25636 (2020).

Mishra, A. et al. Strengthening HIV and HIV co-morbidity care in low-and middle-income countries: Insights from behavioural economics to improve healthcare worker behaviour. J. Int. AIDS Soc.26, e26074 (2023).

Team Behavioural Insights. East. Four Simple Ways to Apply Behavioural Insights. Available at: https://www.bi.team/publications/east-four-simple-ways-to-apply-behavioural-insights/ (2024).

McGrady, M. E., Pai, A. L. & Prosser, L. A. Using discrete choice experiments to develop and deliver patient-centered psychological interventions: A systematic review. Health Psychol. Rev.15, 314–332 (2021).

Wulandari, L. P. L. et al. Preferences for pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV: A systematic review of discrete choice experiments. EClinicalMedicine51, 101507 (2022).

Beckham, S. W., Crossnohere, N. L., Gross, M. & Bridges, J. F. Eliciting preferences for HIV prevention technologies: A systematic review. Patient Patient Cent. Outcomes Res.14, 151–174 (2021).

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Injectable Treatment for HIV Pre-Exposure Prevention. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-injectable-treatment-hiv-pre-exposure-prevention (2021).

US Food and Drug Administration. Sunlenca/Lenacapavir Receives FDA Approval as a First-in-Class, Twice-Yearly Treatment Option for People Living With Multi-Drug Resistant HIV. Available at: https://www.gilead.com/news-and-press/press-room/press-releases/2022/12/sunlenca-lenacapavir-receives-fda-approval-as-a-firstinclass-twiceyearly-treatment-option-for-people-living-with-multidrug-resistant-hiv (2022).

Clark, M. D., Determann, D., Petrou, S., Moro, D. & de Bekker-Grob, E. W. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: A review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics32, 883–902 (2014).

Veldwijk, J., Lambooij, M. S., de Bekker-Grob, E. W., Smit, H. A. & de Wit, G. A. The effect of including an opt-out option in discrete choice experiments. PloS One9, e111805 (2014).

Bech, M., Kjaer, T. & Lauridsen, J. Does the number of choice sets matter? Results from a web survey applying a discrete choice experiment. Health Econ.20, 273–286 (2011).

de Bekker-Grob, E. W., Donkers, B., Jonker, M. F. & Stolk, E. A. Sample size requirements for discrete-choice experiments in healthcare: A practical guide. Patient Patient Cent. Outcomes Res.8, 373–384 (2015).

Giergiczny, M., Dekker, T., Hess, S. & Chintakayala, P. K. Testing the stability of utility parameters in repeated best, repeated best-worst and one-off best-worst studies. Eur. J. Transp. Infrastruct. Res.https://doi.org/10.18757/EJTIR.2017.17.4.3209 (2017).

Huls, S. P., Lancsar, E., Donkers, B. & Ride, J. Two for the price of one: If moving beyond traditional single-best discrete choice experiments, should we use best-worst, best-best or ranking for preference elicitation?. Health Econ.31, 2630–2647 (2022).

Hole, A. DCREATE: Stata module to create efficient designs for discrete choice experiments (2017).

Carlsson, F. & Martinsson, P. Design techniques for stated preference methods in health economics. Health Econ.12, 281–294 (2003).

Hauber, A. B. et al. Statistical methods for the analysis of discrete choice experiments: A report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis good research practices task force. Value Health19, 300–315 (2016).

Chetty-Makkan, C. M. et al. Youth preferences for HIV testing in South Africa: Findings from the Youth Action for Health (YA4H) study using a discrete choice experiment. AIDS Behav.25, 182–190 (2021).

Ghijben, P., Lancsar, E. & Zavarsek, S. Preferences for oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: A best–best discrete choice experiment. Pharmacoeconomics32, 1115–1127 (2014).

Galárraga, O. et al. iSAY (incentives for South African youth): Stated preferences of young people living with HIV. Soc. Sci. Med.265, 113333 (2020).

Operario, D. & Restar, A. Gender-affirmative systems needed for PrEP implementation. Lancet HIV7, e799–e800 (2020).

Minalga, B. et al. Research on transgender people must benefit transgender people. Lancet399, 628 (2022).

Sevelius, J. M., Deutsch, M. B. & Grant, R. The future of PrEP among transgender women: The critical role of gender affirmation in research and clinical practices. J. Int. AIDS Soc.19, 21105 (2016).

Restar, A. et al. Mapping community-engaged implementation strategies with transgender scientists, stakeholders, and trans-led community organizations. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep.20, 160–169 (2023).

Thompson, H. M., et al. First they came for us all: responding to anti-transgender structural violence with collective, community-engaged, and intersectional health equity research and advocacy. Health Educ. Behav.51(1), 5–9 (2024).

Thaler, R. H. & Sunstein, C. R. Nudge: The Final Edition (Yale University Press, 2021).

Lelutiu-Weinberger, C., English, D. & Sandanapitchai, P. The roles of gender affirmation and discrimination in the resilience of transgender individuals in the US. Behav. Med.46, 175–188 (2020).

Feldman, J. L., Luhur, W. E., Herman, J. L., Poteat, T. & Meyer, I. H. Health and health care access in the US transgender population health (TransPop) survey. Andrology9, 1707–1718 (2021).

Scheim, A. I., Baker, K. E., Restar, A. J. & Sell, R. L. Health and health care among transgender adults in the United States. Annu. Rev. Public Health43, 503–523 (2022).

Hiransuthikul, A. et al. Drug-drug interactions between feminizing hormone therapy and pre-exposure prophylaxis among transgender women: The iFACT study. J. Int. AIDS Soc.22, e25338 (2019).

Cattani, V. B. et al. Impact of feminizing hormone therapy on tenofovir and emtricitabine plasma pharmacokinetics: A nested drug–drug interaction study in a cohort of Brazilian transgender women using HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.77, 2729–2736 (2022).

Grant, R. M. et al. Sex hormone therapy and tenofovir diphosphate concentration in dried blood spots: Primary results of the interactions between antiretrovirals and transgender hormones study. Clin. Infect. Dis.73, e2117–e2123 (2021).

Morris, E. et al. Characteristics associated with pre-exposure prophylaxis discussion and use among transgender women without HIV infection—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance Among Transgender Women, seven urban areas, United States, 2019–2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep.73(1), 9–20 (2024).

Pinto, R. M., Berringer, K. R., Melendez, R. & Mmeje, O. Improving PrEP implementation through multilevel interventions: A synthesis of the literature. AIDS Behav.22, 3681–3691 (2018).

Melendez, R. M. & Pinto, R. M. HIV prevention and primary care for transgender women in a community-based clinic. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care20, 387–397 (2009).

Restar, A. et al. Gender affirming hormone therapy dosing behaviors among transgender and nonbinary adults. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun.9, 1–11 (2022).

Kennedy, C. E. et al. Self-administration of gender-affirming hormones: A systematic review of effectiveness, cost, and values and preferences of end-users and health workers. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters29, 2045066 (2022).

Rael, C. T. et al. Transgender women’s concerns and preferences on potential future long-acting biomedical HIV prevention strategies: The case of injections and implanted medication delivery devices (IMDDs). AIDS Behav.24, 1452–1462 (2020).

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first injectable treatment for HIV pre-exposure prevention. FDA. gov. (2021).

Li, D. H. et al. Determinants of implementation for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis based on an updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: A systematic review. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr.90, S235–S246 (2022).

Salinas-Rodríguez, A. et al. Preferences for conditional economic incentives to improve pre-exposure prophylaxis adherence: A discrete choice experiment among male sex workers in Mexico. AIDS Behav.26, 833–842 (2022).

de Aguiar Pereira, C. C. et al. Preferences for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among sexual and gender minorities: A discrete choice experiment in Brazil. Lancet Reg. Health Am.19, 100432 (2023).

Galárraga, O. & Sosa-Rubí, S. G. Conditional economic incentives to improve HIV prevention and treatment in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet HIV6, e705–e714 (2019).

Operario, D., Kuo, C., Sosa-Rubí, S. G. & Gálarraga, O. Conditional economic incentives for reducing HIV risk behaviors: Integration of psychology and behavioral economics. Health Psychol.32, 932 (2013).

Galárraga, O., Genberg, B. L., Martin, R. A., Barton Laws, M. & Wilson, I. B. Conditional economic incentives to improve HIV treatment adherence: Literature review and theoretical considerations. AIDS Behav.17, 2283–2292 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all of the study participants for their time and attention completing the survey. Our gratitude goes out to our study’s advisory board, the Transgender and Nonbinary Collective in Research Equity from Washington. We also thank Tim Souza, Senior Data Scientist at Brown University, for programming the Discrete Choice Experiment, and Dr. Renee Heffron at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for their mentorship, support, and insights into PrEP studies in Washington.

Funding

This study is sponsored by the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research and Behavioral Research Center for HIV under grants AI027757 and P30MH123248, respectively. Dr. Restar is supported by the Research Education Institute for Diverse Scholars (REIDS) Program at Yale University School of Public Health, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (R25MH087217), the Weitzman Institute at the Moses/Weitzman Health System, amfAR, the Foundation of AIDS Research, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Research Fellowship. We are grateful to the Population Studies and Training Center at Brown University, which receives funding from the NIH (P2C HD041020), for general support. This article does not represent the official view of the sponsors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.R. obtained the funding that supported this discrete choice experiment. A.R., O.G., and D.O. led the study’s conception and design. A.R. and E.D. led the data acquisition. M.W.B. led data analysis and interpretation, with expert guidance from O.G. A.R. and E.D. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division (IRB #:STUDY00015878).

Consent to participate

Written electronic informed consent, which included consent to publication, was obtained from all enrolled study participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Restar, A., Wilson-Barthes, M.G., Dusic, E. et al. Using stated preference methods to design gender-affirming long-acting PrEP programs for transgender and nonbinary adults. Sci Rep 14, 23482 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72920-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72920-z