Abstract

We aimed to describe facial directional asymmetry (DA) in individuals with different manifestations of laterality. Due to the overlap between brain and face development, a relationship between the manifestation of brain laterality and DA is hypothesised. These findings could clarify the relationship between the brain and facial phenotype and help to plan facial or oral motor rehabilitation. The DA of 163 healthy individuals was assessed by two complementary 3D methods: landmark and polygonal surface analysis using colour-coded maps. Handedness was assessed using the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory, while chewing side and eye preferences were self-reported. The results showed a similar DA pattern regardless of sex and laterality (the right-sided protrusion of the forehead, nose, lips, and chin) and a slightly curved C-shape of the midline in landmark analysis. A relationship between lateralized behaviours and DA was found only in males, in females the DA pattern was more homogenous. Right-handed individuals and right-side chewers showed a protrusion of the right hemiface. Males, left-handed and left-side chewers, manifested a protrusion of the left lateral hemiface. We suggest that these specific differences in males may be due to their typically higher level of brain asymmetry. No apparent relationship was found between eyedness and DA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The human craniofacial complex plays a significant role throughout life. It develops throughout an individual’s life and has a certain degree of asymmetry that can change at different stages of life. It is affected by nutrition intake, communication, speech, and expressions of feelings and emotions1. Facial asymmetry itself has been studied repeatedly in relation to handedness, which is the main manifestation of brain laterality2,3,4,5. There are also other manifestations of brain laterality, such as chewing side preference6,7, preference for one side of mimetic muscles8,9, or preference for one eye and one foot2,10, where some association with facial asymmetry has been found.

During the prenatal period, there are three main interactions which suggest that the brain plays a role in facial morphogenesis. Therefore facial development (and facial asymmetry as well) is highly dependent on healthy brain development11. First, the face and brain have common neuroectodermal origin11,12. Furthermore, the timing of the development is very similar13. Brain development begins during the 3rd week and during the 4th week, the facial primordia appear around the stomodeum. At approximately the 33rd day, the frontonasal prominence surrounds the forebrain (telencephalon)14. Then, between 7th and 10th weeks there is a fusion of medial nasal prominences with each other and with the lateral nasal and maxillary prominences. By 14th week, the major facial formation is complete13,14. In the same period, lateralization of brain begins15,16,17. In 10th week, a study of ultrasound scans showed that 85% human foetuses moved their right arms more than the left15. Moreover, during the second and third trimester, there is a significant expansion of the brain in size and shape13. The second brain-face interaction is that the brain serves as a structural platform for the face. This interaction applies physical forces to nearby tissues and guiding where and how facial parts grow11. Thirdly, there are molecular interactions and pathways that regulate the cellular mechanisms within tissues (e.g. gradient of SHH factor)11,14. These interactions allow us to link facial morphology with brain development and lateralization18,19.

The degree of asymmetry of the face and its aesthetics are an essential parameter because they are involved in all social interactions and choosing a partner20,21. Facial directional asymmetry (DA), is kind of asymmetry where left-right differences in average differ from zero22 and therefore on human face perform as deviation (in one direction) from symmetrical average23,24. DA affects the whole face in many ways, but each part of the face can manifest differently – with different degrees of DA24. Ideally symmetrical faces are considered to be the most aesthetic and therefore the most attractive. However, even in healthy individuals, there is always some degree of facial DA, and its manifestation determines the functionality and aesthetics of the whole face25.

Facial asymmetry changes and develops during the prenatal26 and postnatal24,27 life. Prenatal changes are determined by genetics28,29, and normal13 or pathological30 developmental processes can be influenced by exposure to external substances, such as alcohol31. Postnatally, there are important factors for changes in morphology and asymmetry, including lifestyle32, craniofacial growth and maturation, dental changes, and age-related degenerative processes33. Age-related changes in the craniofacial complex have a significant effect on facial asymmetry24,34, and there are studies that showed an increase in facial asymmetry with age34,35. On the other hand, there is also a study that showed a pronounced asymmetry in males up to the age of 40 years, while females did not show any significant age-related changes in DA24. Nevertheless, studies of facial ageing have shown that between the ages of 30 and 60, there is an intensive loss of tissue volume in the cheeks and temporal area36, and between the ages of 40 and 50, there is a drop of the eyebrows and upper eyelids37. As indicated above, males and females show some differences in facial asymmetry, especially in young and middle age, while after middle age, facial asymmetries between the sexes become more similar24. These DA differences are not very profound, and males show a greater variability in facial asymmetry38,39.

A variable that is often correlated with facial asymmetry is hand preference – or handedness3,4,8,40. In the average population, there are approximately 10% left-handed people, with the rest of the population being predominantly right-handed5. Handedness is considered to be a manifestation of brain hemispheric laterality, where the right hand is in general controlled by the left motor cortex and vice versa41,42. Additionally, functional manifestation and relatively strict contralateral controlling by the brain hemisphere are more common in right-handers. In left-handers, a wider variability in hemisphere dominance for language and motor activity occurs. This suggests that left-handers have less asymmetrical brains43. Visuospatial and also nonverbal functions in right-handers are mostly controlled by the right hemisphere44. There is a correlation with the right hemisphere control of emotions and its functional manifestation on the left side8 and the left hemisphere control of language and contralateral mouth opening on the right side45.

More specifically, according to a review by Budisavljevic et al.46, there is a structural connectivity of interhemispheric and intrahemispheric white matter pathways which differ between right- and left-handers (left-handers are better able to modulate hand use). There are four main brain tracts associated with handedness: the corpus callosum (commissural tract), the corticospinal tract (projection tract), the superior longitudinal fascicle (association tract), and the arcuate fascicle (which supports language functions). Howells et al.47 argue that the asymmetry of the dorsal branch of the superior longitudinal fascicle (responsible for visuospatial integration and fine motor control) highly correlates with the degree of lateralisation. Self-reported right- and left-handed individuals equally exhibited a significant right asymmetry in this tract, but with stronger right lateralisation in left-handed individuals.

Facial DA and its relationship to handedness have been described in many studies2,4,48,49, but the results of these studies are inconsistent. In general, right-handed individuals tend to have a larger left side of the face, while left-handed individuals show a similar but reversed trend, which is usually only marginally significant3,48,49. Between studies, there are some differences in this overall trend, particularly due to variations in methodology. Dane et al.3 reported that the mean left face region was larger in right-handers. Özener et al.48, used a landmark and measurement methodology for asymmetry assessment, also found that the left side of the face is larger in right-handers, especially in the central facial region. At the same time, this asymmetry pattern was more prominent in the lower face for males and in the upper face for females. KelesL et al.49 divided the whole face into triangles and found that right-handers showed larger left-sided: four different triangle areas (including maxillar areas), and total facial area. The overall tendency for the contralateral facial hemiface to be larger in relation to the preferred hand has been found to be more pronounced in right-handers than in left-handers48,49. In left-handers, the right sided areas appeared to be larger, but the side differences were small or insignificant49.

On the other hand, there is a study of Měšťák4. This study focused primarily on nose asymmetries (volume of nasal cavity and nose tip direction). However, some overall differences between right- and left-handers were observed. It was found out that the bigger and more prominent facial side was the same as the preferred side for the hand. There was also a noticeable downward shift of the left eye in right-handers4.

In terms of the chewing side preference, studies consistently show that there are more right-sided chewers than left-sided, although the percentages may vary6,40,50. The most common percentage representation for right-sided preference in chewing is approximately 70–80%6, although this can depend on food texture. Unilaterality becomes more prominent during the chewing of harder foods51. A corresponding pattern with handedness, involving contralateral hemisphere regulation, has also been observed. During rhythmic chewing movements, blood oxygen level-dependent signals increase more in the hemisphere contralateral to the chewing side (specifically in the sensorimotor cortex)52. From the perspective of DA, it has been observed that the side contralateral to the dominant chewing side is usually larger in the chin area53,54 in all individuals, regardless of handedness. These results have been observed in monozygotic and dizygotic twins, suggesting that there is a significant functional effect53. On the other hand, there are studies indicating that the more developed side of the face corresponds to the dominant chewing side7. More than 33% of the population consists of left-eye dominant individuals55. Eye dominance is most often associated with the involuntary eyebrow raising on the side of the dominant eye. This type of asymmetry can then be observed in the upper third of the face56.

Outside the normal range of facial asymmetries, there are numerous dentofacial deformities that increase facial asymmetry not only aesthetically but also often functionally. These increased asymmetries are typically associated with abnormal neurodevelopmental processes due to their close relationship during the prenatal period13. The most common pathologies resulting in facial asymmetry are skeletal classes II and III57, facial palsy58, and cleft lip and/or palate59. Treatment of facial asymmetry, not only in patients with craniofacial deformities, is based on the individual needs of the patient and aims at a more symmetrical and functional face25. The entire treatment process of facial asymmetry relies on orthodontic therapy60, aesthetic medicine, reconstructive or plastic surgery4,61, or a combination of these.

We aimed to describe facial DA in three groups: (1) right- and left-handed individuals (handedness), (2) individuals with different chewing side preferences, and (3) individuals with different eye preferences (eyedness). We chose these three types of preference to include at least one group covering muscular preference, one group covering manifestation of sensory laterality, and one group covering chewing side preference as a representative of direct muscle load. This should provide a complex perspective on the relationships under investigation. Since the connection of handedness and facial DA has been described before, but with inconsistent results, we decided to use advanced 3D virtual methods to assess asymmetry. Additionally, we complemented the results with two other lateralities that could significantly affect facial asymmetry independently of handedness. Our main hypothesis was that there would be a relationship between facial DA pattern and handedness. According to Měšťák4, this relationship should be manifested in a more pronounced right hemiface in right-handed individuals and a more pronounced left hemiface in left-handed individuals. We also assumed that the area of the eye and buccal areas would be more prominent on the same side of the face as the dominant hand. We hope that a correct description and interpretation of the relationship between handedness and facial asymmetry will help to clarify and understand the processes involved in the formation of asymmetry and handedness throughout one’s lifespan. Moreover, from a clinical point of view, these results will help to guide orthodontic and surgical treatment.

Methods

Ethics statement and informed consent

The Institutional Review Board of Charles University, Faculty of Science, Prague, Czech Republic, approved the present study (approval number 2024/06) and we confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All study subjects participated voluntarily and provided a signed (by them and/or by their legal guardians) written informed consent for long-term research.

Material

A total of 163 3D facial surface scans of Czech and Slovak adults were used for this study (Table 1). The dataset was collected cross-sectionally between 2021 and 2023 and was represented by 81 males and 82 females. The age of the subjects ranged from 18 to 55 years, with a mean age of 27.22 ± 7.11 years for males and 29.09 ± 12.11 years for females. The BMI of each individual was between 18.5 and 25, which is a normal body mass index according to the World Health Organization classification62. All adults were without dental, craniofacial, skin, or hand traumas (with consequences) and without anomalies (congenital or secondarily gained). They had not undergone any dental, facial, or hand surgery; and they had not had any dermal fillers. Subjects with significant facial or hand pathology, as well as subjects with significant changes in the number of teeth, were excluded from participating in this study. During the sampling, we controlled for the use of alcohol, drugs, and hormonal medications and excluded these subjects from participating in this study as well. Due to the nature of this study, only subjects who were not forced to change their dominant hand were included.

3D model acquisition

All subjects were scanned using the 3dMDface optical scanner. This scanner is widely used by researchers63,64 and also by medical institutions65,66. This scanner provides robust opportunity for assessing normal and also pathological faces. It utilises a synchronised dual-camera system, enabling it to create a 3D polygonal mesh of the object with a colour texture. This scanning method is safe for living subjects, convenient, and non-invasive. Each individual scan was captured using a system of synchronised stereo pairs – six machine vision cameras and an industrial flash system with a capture speed of ~ 1.5 milliseconds. The process of rendering the final 3D polygonal mesh (x, y, z coordinate system) took seven seconds, and the accuracy of the mesh geometry was established at < 0.2 millimetres or less. Each individual was scanned in an ear-to-ear field of view (180-degree face capture), without significant facial hair, which can cause holes and errors in the meshes, and without any unwanted movement. All individuals were scanned with a neutral facial expression and a closed mouth. Individuals were rescanned if there was any movement during the scan or if the facial expression was not completely neutral.

3D model processing

The 3D surface models were processed using the RapidForm 2006 software67. In this software, all holes and mesh errors were removed. Meshes were decimated to approximately 25k vertices. Further steps were performed in the Morphome3cs II software (polygonal surface analysis)68 and MorphoJ 2.0 software (3D landmark analysis)69. The 3D landmark analysis was the first step in the detailed description of the asymmetry because it allows the researcher to see right–left and cranio–caudal shifts. In terms of methodology, it is a simpler approach that will be further developed in the following section with more detailed analyses yielding different types of results based on the whole surface. These two analyses, landmarks and surface, are independent of but complementary to each other.

3D landmark analysis

Landmark analysis can provide information about the manifestation of asymmetry in the right–left and cranio–caudal direction. However, unlike mesh analysis, landmark analysis can only describe areas covered by landmarks. This means that the method is fast, computationally undemanding, and provides essential information about shape, but it is not as accurate as polygonal surface analysis.

The Cartesian coordinates (x, y, z) of eleven digitised landmarks (Fig. 1) were also used separately for landmark asymmetry analysis. The entire dataset was digitised by the same technical operator (to eliminate interobserver error) and processed largely in the MorphoJ software69. For the overall configuration of all Cartesian coordinates (composed of unpaired and paired landmarks), the Procrustes fit (generalised Procrustes analysis, GPA) was used. Following the GPA, the coordinate configuration was divided into asymmetrical and symmetrical components. The asymmetrical component represents the difference between a completely symmetrical configuration and the original landmark configuration. The Procrustes Analysis of Variance (Procrustes ANOVA) was then performed to assess the presence or absence and the degree of manifestation of the DA in each group separately (four different Procrustes ANOVAs for four groups in each variable of left-/right-side dominant males and females). For each Procrustes ANOVA, the default variables were used – individual effect and DA effect.

The assumptions for parametric tests were not violated. The statistical significance level was set at 0.05 for all tests except Box’s M-test, where the significance level was set at 0.001. For multiple comparisons, the Bonferroni correction70 was used, with the significance level set at 0.00625 for multiple Procrustes ANOVAs (significance level 0.05 / number of tests 8 = corrected significance level 0.00625).

To measure the intraobserver error and the interobserver error (landmark placement error), landmarks were digitised five times on ten 3D models (on five males and on five females) by the original operator and also by a second technical operator. Both landmark placement error measurements were observed on the same subset of data. The Morphome3cs software was used to calculate placement errors, both in millimetres. The calculation of the measurement error follows the methodology71.

The mean landmark placement error for the main technical operator who digitised the entire dataset and the data subset for the measurement error was determined at ± 0.38 mm. The mean landmark placement error for the second operator, who digitised the data subset to establish the measurement error, was determined at ± 0.52 mm. The mean of the interobserver error between the digitisation of the two technicians was determined at ± 0.65 mm. The landmark placement error (both intraobserver and interobserver) did not exceed 1 mm.

Landmarks were created in Morphome3cs II and used for landmark shape asymmetry analysis and for rigid mesh pre-alignment prior to coherent point drift-dense correspondence analysis. Eight landmarks are paired and three on the facial midline are unpaired. Numbers 1, 4 are exocanthions, endocanthions are 2, 3. Numbers 8, 9 are cheilions, alare landmarks are 10, 11. On the facial midline, number 5 represents nasion, 6 is pronasale, and 7 is gnathion.

Polygonal surface analysis using colour-coded maps

Polygonal surface analysis makes it possible to describe the manifestation of asymmetry in the protrusive–retrusive (antero-posterior) direction. This method is very accurate, objective, and can be used to describe areas that cannot be covered by landmarks. In this way, it assesses the entire polygonal mesh. The disadvantage of this method is that it does not evaluate right–left and cranio–caudal shifts, but this gap is filled by the complementary 3D landmark method.

Mesh shape analysis and visualisation were performed using the Morphome3cs software68, while vertex homology was generated using coherent point drift-dense correspondence analysis (CPD-DCA)72. At the start of the analysis, eleven 3D anatomical landmarks (Fig. 1) were placed on each 3D model and then were used for a rigid pre-alignment of the models. A random base face mesh was selected as a template for alignment, and its vertices were then automatically transferred to all meshes. The registration of the base mesh to the other meshes was performed using CPD73, which is a fully automated non-rigid registration algorithm. Vertex homology was ensured by projecting the vertices of the deformed base mesh onto the closest points on all other meshes. Vertices that could not be matched were removed from the study. After the CPD-DCA analysis, the vertices can be evaluated as 3D landmarks (also known as ordinary landmarks or quasi-landmarks). For the final alignment of the resampled meshes, the generalised Procrustes analysis (GPA) was used. To achieve a calculation of the face DA, it is essential to use a mirror copy of all the meshes in the dataset and to register these mirrored copies to their originals. The mirroring of meshes was automatically performed by adding an opposite spatial position to paired mesh landmarks – paired landmarks swapped their positions with their mirror counterparts, unpaired landmarks were not affected by the mesh mirroring74.

The DA of the face shape was visualised on the 3D mesh by colour-coded face maps, one average shape map for each group and one colour-coded map for the difference between two average shapes of two groups. Warm colours (i.e., shades of red, with dark red being the most protrusive) indicate protrusion and anterior shifts of the facial areas, whereas cool colours (i.e., shades of blue, with dark blue being the most retrusive) indicate retrusion and posterior shifts of the facial areas. Shades of green or white indicate neutral areas without any protrusion or retrusion, or they indicate no difference between two groups. Superimposition was used to show differences between the shape averages of right- and left-dominant groups, again using colour-coded maps – warm shades (red) show protrusive areas, and cool shades (blue) show retrusive areas. In each superimposed colour-coded map, the second visualised group was compared with the first group, meaning that during the interpretation, the maps for left-dominant individuals (second group) were described in contrast to right-dominant individuals (first group).

Results

3D landmark analysis

First, the significance of the DA on the level of 3D landmarks was tested. The DA calculated from the landmarks was statistically significant in most groups. The Procrustes ANOVA (Table 2) showed that the DA was not significant in left-chewing males and females, in left-eye preferring males, and both-eye preferring males and females. The individual shape variability was significant in each tested group (p-value = < 0.0001).

Following the Procrustes ANOVA, all landmark data, including groups with non-significant Procrustes ANOVA results, were visualised using wireframe graphs. This was done to allow complex visual comparison with the more detailed method of the polygonal surface analysis.

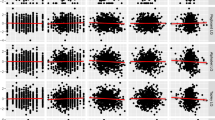

For the DA in the handedness groups, the wireframe graphs (Fig. 2, Part C) showed that the facial midline was slightly shifted to the left side, particularly in the area of the nasion and gnathion. This shape of midline formed a slightly curved letter C in both right- and left-handed individuals. Overall, right-handed males and females showed a very similar pattern of asymmetry, while left-handed females were less asymmetrical.

The wireframe graphs for chewing side preferences (Fig. 3, Part C) generally showed a shifted facial midline forming a slightly curved letter C. This pattern was the most evident in the right-side chewing preference in both sexes. Females with a left- and both-side chewing preference showed the least pronounced DA pattern. Males with left- and both-side chewing preference showed a similar manifestation of DA as right-chewing males, but it was less pronounced, especially in the left-chewers.

The landmark visualisation of DA based on eyedness (Fig. 4, Part C) largely followed the trend of the letter C represented by the facial midline. Apart from this pattern of asymmetry, there was a more pronounced asymmetry in groups with a preference for both eyes. In females in this group, the right eye was lower than the symmetrical mean.

Polygonal surface analysis – handedness

Polygonal surface analysis was carried out to complement the previous simplified wireframe graphs and was used to describe changes in terms of protrusion and retrusion across the whole surface model. These results therefore provide information on shifts in asymmetry in directions other than the 3D landmarks. Although the two analyses are used independently, they complement each other, which was also supported by our results. To provide a better visualisation of the two approaches, we combined them into one figure for each group.

First, we observed that there was no difference between the DA of self-reported and EHI-calculated right- and left-handers (Fig. 2, Part D). All facial areas were coloured in shades of green, representing neutral areas with no differences between the groups.

In general, the colour-coded maps showed a more protrusive right forehead and midsagittal area (nose, lips, and parts of the chin) in both right- and left-handed males (Fig. 2, Part A). Right-handed males showed a very protrusive right edge of the face and right buccal area. Left-handed males showed the opposite trend – a more protrusive left hemiface and left orbital area. In left-handed males, there was also a marked retrusion of the left upper lip area, which may indicate developmental disturbances.

In females (Fig. 2, Part A), the results showed that right- and left-handed individuals were similar to each other, both with a pattern of more protrusive right forehead and midsagittal area (nose, lips, and chin). There were only small differences between right- and left-handed females. Additionally, the pattern of the facial DA in left-handed females was also similar to the pattern of left-handed males.

Comparing the DA of males and females, it is evident that the DA was more pronounced in males than in females. Female faces were characterised by a lower degree of DA than males and had more neutral areas without asymmetry, while asymmetrical areas were evenly distributed across the whole face. Some areas of the face had the same pattern regardless of hand preference or sex (right-side prominence of the forehead, nose, lips and chin), while others differed (lateral parts of the face).

Maps describing the differences in DA between right-handed and left-handed males and females (Fig. 2, Part B) show the following trends. Both left-handed males and females have a more prominent area of the right eye and left cheek. Right-handed males have a more protruding right side of the face, while right-handed females have the opposite tendency – a more protruding left side of the face. The right side of the chin was more protrusive in right-handed males and in left-handed females.

(A) Facial DA based on polygonal surface analysis for right- and left-handed males and females separately. The DA is visualised using colour-coded 3D maps. Warm colours (shades of red) indicate protrusive areas, cool colours (shades of blue) indicate retrusive areas. Areas showed in green are asymmetrically neutral. The threshold on the asymmetry scale was set to 0.002. (B) Differences in DA between right- and left-handed individuals calculated by the polygonal surface analysis and visualised by colour-coded 3D maps. Red shades show protruding areas in left-handers, blue shades show protruding areas in right-handers. Areas in white are asymmetrically neutral. (C) Facial DA based on 3D landmark analysis, visualised by wireframe graphs in both sexes. The scaling for the DA was 10×. The grey lines show an ideally symmetrical shape in each tested group. The blue lines (for males) and red lines (for females) show the shape of specific DA next to the symmetrical shape in each group. The green arrows show the range and direction of shifts in facial DA from the ideally symmetrical shape mean. (D) Differences between DA in individuals with self-reported and EHI-calculated handedness, calculated by the polygonal surface analysis. DA visualised by: colour-coded maps in Morphome3cs II software = A, B, D; landmarks in MorphoJ 2.0 software = C. M males, F females, R-handed right-handed, L-handed left-handed.

Polygonal surface analysis – chewing side preference

The colour-coded maps for chewing side preference (Fig. 3, Part A) showed the same trend of the protrusive right forehead and midsagittal area in both sexes. In right-side chewing males, the maps showed a significant protrusion of almost the entire right hemiface, except for the orbital and zygomatic areas. On the left hemiface, there was a visible protrusion in the orbital area. Apart from the protrusive right side of the forehead, midsagittal area, and mouth, males with the dominant left side for chewing showed protrusive left cheeks and the mandibular area. Males with no strict preference for a chewing side showed a similar pattern of DA to right-side chewing males, but with a more significant protrusion of the right forehead.

Maps comparing the two groups of right- and left-chewers (Fig. 3, Part B) showed the following trends. The manifestation of the difference between right- and left-chewers was similar in both sexes. Left-chewers had a more protrusive right side of the forehead, right eye, and left cheek. This trend was more pronounced in males. The only differentiating area in this comparison was the chin, where female left-chewers showed a very slightly protrusive right chin and male left-chewers a strongly retrusive right chin.

(A) Facial DA based on polygonal surface analysis for right- and left-side chewing preference in males and females separately. The DA is visualised using colour-coded 3D maps. Warm colours (shades of red) show protrusive areas, cool colours (shades of blue) show retrusive areas. Areas showed in green are asymmetrically neutral. The threshold on the asymmetry scale was set to 0.002. (B) Differences in DA between right- and left-side chewing preferences in individuals calculated by the polygonal surface analysis and visualised by colour-coded 3D maps. Red shades show protrusive areas in left-chewers, blue shades show protrusive areas in right-chewers. Areas in white are asymmetrically neutral. (C) Facial DA based on 3D landmark analysis, visualised by wireframe graphs in both sexes. The scaling for the DA was 10×. The grey lines show an ideally symmetrical shape in each tested group. The blue lines (for males) and red lines (for females) show the shape of specific DA next to the symmetrical shape in each group. The green arrows show the range and direction of shifts in facial DA from the ideally symmetrical shape mean. DA visualised by: colour-coded maps in Morphome3cs II software = A, B; landmarks in MorphoJ 2.0 software = C. M males, F female, R-chewing right-side chewing, L-chewing left-side chewing, B-chewing both side chewing, R right-side chewing, L left-side chewing.

Polygonal surface analysis – eyedness

The facial DA based on the variable of eyedness is showed in Fig. 4, Part A. We observed two common patterns for both sexes and each eyedness group. First, the DA pattern based on eyedness was similar to the DA pattern based on handedness. Second, there was the same trend of protrusion of the right forehead and right midsagittal area in each eyedness group in both sexes. In addition to the common pattern, each group also showed its own specifics: right-eyed males had protrusive right cheeks and left edges of the orbital and mandibular areas. Left-eyed males showed less protrusive right cheeks and more protrusive left corners of the mouth than right-eyed males. Males with no strict eye preference had a protrusive left orbital area and right lower jaw. In right- and left-eyed females, there was additionally a protrusive left edge of the buccal and zygomatic area, while all protrusions were more pronounced in left-eyed females. Females without a strict eye preference showed a right-side lower jaw protrusion and a very small left-side temporal protrusion.

Maps comparing the two eyedness groups (Fig. 4, Part B) showed that the manifestation of the difference between right- and left-eye preference differed between the sexes. Colour-coded maps showed that left-eyed males had a more protrusive right forehead, left cheek, and mouth, whereas right-eyed males showed the same protrusive areas on the opposite hemiface. In left-eyed females, there were a protrusive left-side forehead, orbital area, and cheeks, and right mouth and chin areas.

(A) Facial DA based on polygonal surface analysis for right- and left-side eyedness in males and females separately. The DA is visualised using colour-coded 3D maps. Warm colours (red) show protrusive areas, cool colours (blue) show retrusive areas. Areas showed in green are asymmetrically neutral. The threshold on the asymmetry scale was set to 0.002. (B) Differences in DA between right- and the left-eyed individuals calculated by the polygonal surface analysis and visualised by colour-coded 3D maps. Red shades show protrusive areas in left-eyed individuals, blue shades show protrusive areas in right-eyed individuals. Areas in white are asymmetrically neutral. (C) Facial DA based on 3D landmark analysis, visualised by wireframe graphs in both sexes. The scaling for the DA was 10×. The grey lines show an ideally symmetrical shape in each tested group. The blue lines (for males) and red lines (for females) show the shape of specific DA next to the symmetrical shape in each group. The green arrows show the range and direction of shifts in facial DA from the ideally symmetrical shape mean. DA visualised by: colour-coded maps in Morphome3cs II software = A, B; landmarks in MorphoJ 2.0 software = C. M males, F female, R-eye right-side eyedness, L-eye left-side eyedness, B-eye both eyes, R right-side eyedness, L left-side eyedness.

Discussion

The present study provides results evaluating facial directional asymmetry in relation to handedness, chewing side preference, and eyedness. Directional asymmetry was described for males and females at the level of 3D landmarks and 3D polygonal meshes, revealing asymmetry patterns that differed between right- and left-handers, as well as between individuals with right or left preferred chewing side.

These findings can help to better describe and understand the relationships between lateralized behaviours and the apparent facial phenotype of individuals throughout their lives. The outputs of this study can serve as healthy standards or populational standards for groups preferring the left versus right hand, eye, or chewing side in planning plastic surgery or oral motor rehabilitation. Furthermore, the results can be used as a comparison material in studies involving other populations. Therefore, there are applications in fields such as neuroscience, biological, evolutionary, and developmental anthropology, and in plastic surgery or orthodontics.

The methodology used in this study comprises a combination of a well-established standard – the 3D landmark method for DA assessment and innovative 3D methods based on assessing the entire surface models. We decided for a combination of these two different methods because they provide different but very compatible results. The 3D landmark methods show shape shifts mainly in the right–left direction (plus cranio–caudal and antero–posterior directions), but they can only provide information about areas with a digitised landmark. Colour-coded maps visualise the whole studied area of the face. They show facial areas with protrusion and retrusion or, in other words, areas with antero–posterior shifts. By combining the results of these two approaches, we got the complex information about the facial DA in any direction.

When studying handedness, it is usually important to know which methods were used for its assessment. First, we used the fastest and easiest method, which is self-reported handedness. This however does not reflect the continual character of hand use for different activities. Another option is to use a standardised questionnaire for handedness. In this study, we chose the widely used Edinburgh Handedness Inventory75. When the colour-coded maps based on self-reported and calculated handedness were compared, we found that these two groups overlapped. This suggests that for the purposes of DA analysis, it is possible to use either self-reported or calculated handedness.

The appearance of the facial DA in the 3D landmarks was significant in almost each tested group, except left-side chewing individuals, left-eyed males, and individuals without any eye side preference. The colour-coded maps showed asymmetry trends in each group. Nevertheless, in groups where the DA was not significant on 3D landmarks, we observed protrusive shifts on the opposite hemiface (from the right to the left side), which can have a symmetrising effect. It suggests that the methodology used can make a crucial difference in the DA analysis, demonstrating that the results are strongly dependent on the methods used, even if they are derived from the same dataset. This can explain why studies concerning DA (Haraguchi et al.,60 Harnádková et al.,24 Ferrario et al.,76 Měšťák4) yield so various and inconsistent results. Our suggestion is to properly assess the value of information provided by each method.

Our 3D landmark sub-analysis showed a slightly curved C-shape of the facial midline, which is consistent with results from our previous study (Harnádková et al.)24. There was no significant difference in the DA between any tested groups. These results suggest that the main differences in asymmetry caused by internal or external factors3,7,18,32 are not particularly apparent on 3D landmark results. We can still observe the pattern of asymmetry where the facial midline is bent to the left side of the face, which indicates a potential for a larger or at least protrusive right side of the face, especially in the upper and lower third of the face. This trend was confirmed by colour-coded maps with protruding right forehead and chin areas in each tested group.

Recent results described visible differences between right- and left-handed individuals, and this trend was more prominent in males. Right-handed males showed a more protrusive right hemiface, while the contralateral hemiface was retrusive. In left-handed males, we observed more protrusive left temporo-zygomatic and posterior lower jaw areas, whereas other areas were protrusive mostly on the right hemiface. These results are in contradiction to other studies3,48,49 whose authors presented the hemiface opposite to the side of the hand preference as more dominant. Our results however agree with the study of Měšťák4 where the more protrusive and bigger side of the face is the same as the dominant side for the hand. The opposite pattern of asymmetry in left-handed individuals was shown by our results partially and especially in males. Overall, the right-side protrusion in left-handed males was less extensive, and left-side protrusion shifts occurred. These results are in accordance with previous studies suggesting that there is a different pattern in right- and left-handers3,4,48,49 and also that in right-handers the asymmetry pattern is more prominent48,49. However, we found that the more prominent hemiface was not opposite to the preferred side for the hand but rather was on the ipsilateral side, while this pattern was found mostly in males. In females, the asymmetry is very similar in both tested groups, which suggests a sexual dimorphism. Roosenboom et al.77 stated that androgens were significant factors affecting facial morphology, while facial asymmetry manifests itself mostly before the age of the decline in sex hormones24. Also, as Geschwind and Galaburda stated17, males showed a higher degree of brain asymmetry, which could lead also to the facial phenotypic differences between the sexes.

At the same time, more than 75% of right-handers prefer the right side for chewing6, and in more than 50% there is a match of the chewing side preference with handedness. Stronger unilateral chewing is present when chewing hard food51. The masticatory muscles are significant strong structures with an effective potential to modulate the DA7,53. Taking these results into account, we know that the chewing side preference modulates right–left asymmetry in the sense that there is a shift of protrusion to the left hemiface in left-chewers in the lower part of the face. For the right-side chewing preference, there is a right-side hemifacial protrusion. In females this trend is only slightly noticeable. In the group of individuals with no side preference for chewing, the DA pattern corresponds with the DA patten for right-handers. According to Heikkinen et al.53 and Nascimento et al.54, the side contralateral to the preferred chewing side is usually more prominent and protrusive. In our results, it was the ipsilateral side, which agrees with the study of Tiwari et al.7 Apart from the chewing muscles, the DA can also be affected by mimetic muscles8. This suggests that facial muscles are involved in forming DA by enlarging the hemiface with the preferred muscles. For the examination of the effect of mimetic muscles, it is necessary to use a different type of data, and it is thus beyond the scope of this study. Nevertheless, it could be an occasion for further studies to describe the dynamics of facial asymmetry during facial expressions.

Facial directional asymmetry calculated based on the eyedness variable did not show any specific pattern. In contrast, Shah et al.56 stated an elevation of the eyebrow on the dominant eye side. According to Bourassa et al.55 the odds ratio for handedness and eyedness concordance is 2.53. This means that 57.14% of left-handers and only 34.43% of right-handers are individuals who prefer their left eye. This finding suggests that left-eyed individuals may share more similarities with left-handers, while right-eyed individuals may be more similar to right-handers. Our results showed that the DA pattern for eyedness was similar to the DA pattern in handedness groups, and this similarity was more pronounced in right-handed and right-eyed individuals. On the contrary, Rogers78 stated that with animal models (such as in primate species), a discrepancy was found between specialization of the hemispheres and eyedness or handedness.

We found two common asymmetry patterns in each tested group. The first one was the right-side forehead protrusion (regardless of sex, handedness, chewing side preference, or eyedness). Because this pattern was systematic in each group and also in a study of medieval skulls79, we assume that this asymmetry could be caused by a systematic morphological brain asymmetry. While developing, the brain is the main driver for the head formation and growth13, so we have to focus also on the morphological asymmetries of the brain. What is very common is the Yakovlevian torque. It is a physiological geometric asymmetry of the brain hemispheres, where the right frontal cortex protrudes anteriorly and the left occipital pole protrudes posteriorly80,81. Patterns such as the Yakovlevian torque are visible on the face and skull79, and they can therefore affect the final craniofacial asymmetry. Another factor affecting this asymmetry could be the sleeping position during early childhood82, however, we have no evidence to support this positioning theory.

Another common asymmetrical pattern was in the right nasal ala area, which was relatively protrusive, except in groups of left-handers and left-side chewing males, where the protrusion was only small. A study by Hun et al.83 showed similar results, and in addition, they proved a wider right hemiface and right nasal septum deviation. There is also a correlation with a study by Měšťák4, where this asymmetry and deviation have been linked to differences between right- and left-handers. Other studies3,4,84 also showed a relationship between facial asymmetry and handedness and with brain asymmetries8,46,51,81. Overall, it may lead to the interpretation that facial muscles are more strongly developed on the dominant side of the face, with the majority of the population being right-handed or having a dominant right side of the body5. Therefore, we observed mainly a more protrusive right side of the face. According to Lindell8, the lower part of the facial hemiface innervated by facial nerve is controlled by the contralateral brain hemisphere, and the upper part is controlled by a combination of both hemispheres. This can cause that especially the lower part of the hemiface contralateral to the dominant hemisphere will be more used and therefore more prominent.

An observation worth mentioning in our results is that left-handed males showed a quite visible left-side retrusion on the upper lip. The left-side upper lip is commonly an area where a unilateral cleft (lip, palate) occurs. At the same time, there is an overall higher percentage of males with cleft13. Yorita et al.85 reported that there was a higher probability of left-side cleft in non-right-handers, however, it was independent of sex. The theory of Geschwind and Galaburda17 offered the interpretation that this upper lip protrusion could be the result of developmental differences and instability in left-handed males, which more often leads to clefts.

Study limitations

Studies assessing facial directional asymmetry face many limitations, particularly of a methodological nature. In our study, we selected the best possible methods for assessing asymmetry; however, it is still important to mention the study´s limitation. Firstly, there is a difference in using 2D and 3D data. In general, 3D data are considered to be more precise and shows variability in each spatial direction. But 3D scanners are expensive, and not every department has the opportunity to work with them. Combination of these two approaches across institutions are a potential source of results inconsistency.

Secondly, across asymmetry studies, there are different approaches how to calculate DA. Most commonly used methods are (1) face mirroring (as in our study, where it is not necessary to precisely detect the symmetry plane) and (2) the definition of a symmetry plane, based on which asymmetry is then determined. Also, this could be a potential source of inconsistencies in results and therefore it is essential to be cautious when interpreting the results.

Lastly, handedness determination is, in general, a complex process and varies across many studies (another potential source of result inconsistency). Additionally, it is possible that individuals completing the questionnaire may not provide accurate information, which can significantly affect the results.

Conclusion

The presented study provided a complex and detailed view on the facial DA through two different but complementary methods. A significant DA of landmarks was confirmed for all three types of laterality under investigation (handedness, chewing side preference, and eye preference) with right-side dominance, whereas significant left-side dominance in relation to DA was found only in left-handedness and left-eyed females. Some areas of the face have a similar pattern regardless of the manifestation of laterality or sex. This includes the slightly curved C-shape of the midline according to the 3D landmarks in all evaluated groups of laterality. Furthermore, it includes the right prominence of the forehead and the right prominence of the midsagittal area (nose, lips, and chin), apparent also on the colour-coded maps. Laterality in relation to DA was most pronounced in the lateral region of the face.

We found out that DA has a specific pattern in right-handed and left-handed males. While in right-handed males the whole right hemiface was more protrusive, left-handers showed a protruding left hemiface compared with right-handed males. In females this asymmetry pattern was less obvious, and female faces showed the trend of more symmetrical faces than male faces. Analysing the differences in DA between left- and right-handers, the left lateral face area is more prominent in males and the right lateral face area in females. Another result showed that chewing side preference has a similar impact on the facial DA pattern in males as handedness. Right-side chewers showed a protrusive right hemiface, while in left-side male chewers there was a slight protrusion of the left lateral facial area. Eyedness had no apparent relationship with the facial DA. Finally, we found no difference between the manifestation of DA in self-reported and calculated handedness.

We conclude that there is a connection between DA and specific lateralized behaviours. We find that the connection between facial DA and handedness and chewing side preference is much more apparent in males. We believe that these specific differences could be present in males due to their typically higher level of brain asymmetry and higher level of sex hormones, which are associated with faster growing and progression of maturation. In addition, the mimetic and masticatory muscles on the dominant side are probably involved in the forming of DA. However, there are also other factors which significantly modulate the final facial DA. These factors are not dependent on hemispheric dominance or sex hormones during prenatal and postnatal life.

Data availability

The datasets analysed in the present study are not publicly available due to legal and ethical restrictions such as the preservation of privacy and strict anonymity of the subjects. The human datasets used in this study contain potentially identifying biometric and sensitive individual information. Participants of the study agreed, via informed consent, to publicly share data only in the form of populational averages. Individual information cannot be shared freely in any form (such as facial shape, individual asymmetries, age…). De-identified and strictly anonymised data can be obtained on reasonable request from the corresponding author (harnadkk@natur.cuni.cz).

References

Silbernagl, S. et al. Atlas Fyziologie člověka: překlad 8. německého vydání (Grada Publishing, 2016).

Borod, J. C., Caron, H. S. & Koff, E. Asymmetry of facial expression related to handedness, footedness, and eyedness: a quantitative study. Cortex17, 381–390 (1981).

Dane, Ş., Ersöz, M., Gümüştekin, K., Polat, P. & Daştan, A. Handedness differences in widths of right and left craniofacial regions in healthy young adults. Percept. Mot. Skills98, 1261–1264 (2004).

Měšťák, J. Estetické Operace nosu v klinické Praxi (Grada Publishing, a.s., 2020).

Papadatou-Pastou, M. et al. Human handedness: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull.146, 481–524 (2020).

Nissan, J., Gross, M. D., Shifman, A., Tzadok, L. & Assif, D. Chewing side preference as a type of hemispheric laterality. J. Rehabilit.31, 412–416 (2004).

Tiwari, S., Nambiar, S. & Unnikrishnan, B. Chewing side preference - impact on facial symmetry, dentition and temporomandibular joint and its correlation with handedness. J. Orofac. Sci.9, 22 (2017).

Lindell, A. Elsevier,. Lateralization of the expression of facial emotion in humans. In: Progress in Brain Research vol. 238 249–270 (2018).

Ocklenburg, S. & Güntürkün, O. Language and the left hemisphere. In: The Lateralized Brain 87–121 (Elsevier), https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803452-1.00004-7. (2018).

Akabalieva, K. V. Combined foot and eye dominance scale as a useful tool for the assessment of lateralization. Eur. Psychiatr.66, S1064–S1064 (2023).

Marcucio, R., Hallgrimsson, B. & Young, N. M. Facial morphogenesis. In: Current Topics in Developmental Biology115 299–320 (Elsevier, 2015).

Tripi, G. et al. Cranio-facial characteristics in children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). JCM8, 641 (2019).

Moore, K. L., Persaud, T. V. N. & Torchia, M. G. The developing human: Clinically oriented embryology (Saunders/Elsevier, 2008).

Moore, K. L., Persaud, T. V. N. & Torchia, M. G. Before we are born: Essentials of embryology and birth defects (Elsevier, 2016).

Hepper, P. G., Mccartney, G. R. & Shannon, E. A. Lateralised behaviour in first trimester human foetuses. Neuropsychologia36, 531–534 (1998).

Francks, C. Exploring human brain lateralization with molecular genetics and genomics. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.1359, 1–13 (2015).

Geschwind, N., Galaburda, A. M. Cerebral lateralization: Biological mechanisms, associations, and pathology: I. A hypothesis and a program for research. Arch. Neurol.42, 428 (1985).

Hammond, P. et al. Face–brain asymmetry in autism spectrum disorders. Mol. Psychiatry13, 614–623 (2008).

Lindell, A. K. & Hudry, K. Atypicalities in cortical structure, handedness, and functional lateralization for language in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychol. Rev.23, 257–270 (2013).

Johnston, V. S. Mate choice decisions: the role of facial beauty. Trends Cogn. Sci.10, 9–13 (2006).

Quist, M. C. et al. Sociosexuality predicts women’s preferences for symmetry in men’s faces. Arch. Sex. Behav.41, 1415–1421 (2012).

Klingenberg, C. Analyzing fluctuating asymmetry with geometric morphometrics: concepts, methods, and applications. Symmetry7, 843–934 (2015).

Meyer-Marcotty, P., Stellzig-Eisenhauer, A., Bareis, U., Hartmann, J. & Kochel, J. Three-dimensional perception of facial asymmetry. Eur. J. Orthod.33, 647–653 (2011).

Harnádková, K., Kočandrlová, K., Kožejová Jaklová, L., Dupej, J. & Velemínská, J. The effect of sex and age on facial shape directional asymmetry in adults: a 3D landmarks-based method study. PLoS ONE18, e0288702 (2023).

Pazdera, J. Základy Ústní a Čelistní Chirurgie (Olomouc, 2013).

Katsube, M. et al. Analysis of facial skeletal asymmetry during foetal development using µCT imaging. Orthod. Craniofac. Res.22, 199–206 (2019).

Hood, C. A., Bock, M., Hosey, M. T., Bowman, A. & Ayoub, A. F. Facial asymmetry – 3D assessment of infants with cleft lip & palate. Int. J. Paed Dent.13, 404–410 (2003).

Babczyńska, A., Kawala, B. & Sarul, M. Genetic factors that affect asymmetric mandibular growth—A systematic review. Symmetry14, 490 (2022).

Windhager, S. et al. Variation at genes influencing facial morphology are not associated with developmental iImprecision in human faces. PLoS ONE9, e99009 (2014).

Carstens, M. H. D. F. R. & Cheilorhinoplasty The role of developmental field reassignment in the management of facial asymmetry and the airway in the complete cleft deformity. In: The Embryologic Basis of Craniofacial Structure (ed Carstens, M. H.) 1563–1642 (Springer International Publishing), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15636-6_19. (2023).

Klingenberg, C. P. et al. Prenatal alcohol exposure alters the patterns of facial asymmetry. Alcohol44, 649–657 (2010).

Harastani, M., Benterkia, A., Zadeh, F. M. & Nait-Ali, A. Methamphetamine drug abuse and addiction: effects on face asymmetry. Comput. Biol. Med.116, 103475 (2020).

Kaur, M., Garg, R. K. & Singla, S. Analysis of facial soft tissue changes with aging and their effects on facial morphology: a forensic perspective. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci.5, 46–56 (2015).

Linden, O. E., He, J. K., Morrison, C. S., Sullivan, S. R. & Taylor, H. O. B. The relationship between age and facial asymmetry. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.142, 1145–1152 (2018).

Sajid, M., Taj, I. A. & Bajwa, U. I. Ratyal, N. I. The role of facial asymmetry in recognizing age-separated face images. Comput. Electr. Eng.54, 255–270 (2016).

Wysong, A., Joseph, T., Kim, D., Tang, J. Y. & Gladstone, H. B. Quantifying soft tissue loss in facial aging: a study in women using magnetic resonance imaging. Dermatol. Surg.39, 1895–1902 (2013).

Albert, A. M., Ricanek, K. & Patterson, E. A review of the literature on the aging adult skull and face: implications for forensic science research and applications. Forensic Sci. Int.172, 1–9 (2007).

Alford, R. & Alford, K. F. Sex differences in asymmetry in the facial expression of emotion. Neuropsychologia19, 605–608 (1981).

Claes, P. et al. Sexual dimorphism in multiple aspects of 3D facial symmetry and asymmetry defined by spatially dense geometric morphometrics: spatially dense sexual dimorphism in 3D facial shape. J. Anat.221, 97–114 (2012).

Martinez-Gomis, J. et al. Relationship between chewing side preference and handedness and lateral asymmetry of peripheral factors. Arch. Oral Biol.54, 101–107 (2009).

Ocklenburg, S. & Güntürkün, O. Handedness and other behavioral asymmetries. In: The Lateralized Brain 123–158 (Elsevier), https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803452-1.00005-9. (2018).

McManus, C. Cerebral polymorphisms for lateralisation: modelling the genetic and phenotypic architectures of multiple functional modules. Symmetry14, 814 (2022).

Vingerhoets, G. Phenotypes in hemispheric functional segregation? Perspectives and challenges. Phys. Life Rev.30, 1–18 (2019).

Szaflarski, J. P., Holland, S. K., Schmithorst, V. J. & Byars, A. W. fMRI study of language lateralization in children and adults. Hum. Brain Mapp.27, 202–212 (2006).

Hausmann, M. et al. Sex differences in oral asymmetries during wordrepetition. Neuropsychologia36, 1397–1402 (1998).

Budisavljevic, S., Castiello, U. & Begliomini, C. Handedness and white matter networks. Neuroscientist27, 88–103 (2021).

Howells, H. et al. Frontoparietal tracts linked to lateralized hand preference and manual specialization. Cereb. Cortex28, 1–13 (2018).

Özener, B., Palin, C., Kürkçüoğlu, A., Ertuğrul, B. & Zağyapan, R. Analysis of facial directional asymmetry in extremehanded young males and females. Eurasian J. Anthropol. 96–101 (2011).

KelesL, P., Díyarbakirli, S., Tan, M. & Tan, Ü. Facial asymmetry in right- and left-handed men and women. Int. J. Neurosci.91, 147–159 (1997).

Varela, J. M. F. et al. A comparison of the methods used to determine chewing preference. J. Oral Rehabilit.30, 990–994 (2003).

Khamnei, S. et al. Manifestation of hemispheric laterality in chewing side preference and handedness. Bioimpacts9, 189–193 (2019).

Jiang, H. et al. Analysis of brain activity involved in chewing-side preference during chewing: an fMRI study. J. Oral Rehabilit.42, 27–33 (2015).

Heikkinen, E. V., Vuollo, V., Harila, V., Sidlauskas, A. & Heikkinen, T. Facial asymmetry and chewing sides in twins. Acta Odontol. Scand.80, 197–202 (2022).

Nascimento, G. K. B. O. et al. Preferência De lado mastigatório e simetria facial em laringectomizados totais: estudo clínico e eletromiográfico. Rev. CEFAC15, 1525–1532 (2013).

Bourassa, D. C. Handedness and eye-dominance: a Meta-analysis of their relationship. Laterality1, 5–34 (1996).

Shah, C. T., Nguyen, E. V. & Hassan, A. S. Asymmetric eyebrow elevation and its association with ocular dominance. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg.28, 50–53 (2012).

Severt, T. & Proffit, W. The prevalence of facial asymmetry in the dentofacial deformities population at the University of North Carolina. Int. J. Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg.12, (1997).

Azuma, T. et al. New method to evaluate sequelae of static facial asymmetry in patients with facial palsy using three-dimensional scanning analysis. Auris Nasus Larynx49, 755–761 (2022).

Golshah, A., Hajiazizi, R., Azizi, B. & Nikkerdar, N. Assessment of the asymmetry of the lower jaw, face, and palate in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate. Contemp. Clin. Dent.13, 40 (2022).

Haraguchi, S., Iguchi, Y. & Takada, K. Asymmetry of the face in orthodontic patients. Angle Orthod.78, 421–426 (2008).

Rohrich, R. J., Villanueva, N. L., Small, K. H. & Pezeshk, R. A. Implications of facial asymmetry in rhinoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.140, 510–516 (2017).

WHO. Executive summary of the clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Arch. Intern. Med.158, 1855 (1998).

Kočandrlová, K., Dupej, J., Hoffmannová, E. & Velemínská, J. Three-dimensional mixed longitudinal study of facial growth changes and variability of facial form in preschool children using stereophotogrammetry. Orthod. Craniofac. Res.24, 511–519 (2021).

Velemínská, J. et al. Three-dimensional analysis of modeled facial aging and sexual dimorphism from juvenile to elderly age. Sci. Rep.12, 21821 (2022).

Guo, K. et al. Precise maxillofacial soft tissue reconstruction: a combination of cone beam computed tomography and 3dMD photogrammetry system. Heliyon10, e32513 (2024).

Schwarz, M. et al. Body mass index is an overlooked confounding factor in existing clustering studies of 3D facial scans of children with autism spectrum disorder. Sci. Rep.14, 9873 (2024).

Technology, I. N. U. S. Inc. Rapidform (INUS Technology, Inc, 2006).

Dupej, J. & Krajíček, V. Morphome3cs. (2023).

Klingenberg, C. P. MorphoJ: an integrated software package for geometric morphometrics. (2011).

Bonferroni, C. E. Teoria Statistica delle classi e calcolo delle probabilit `a. Pubblicazioni Del. R Istituto Superiore Di Scienze Economiche E Commerciali Di Firenze 3–62 (1936).

von Cramon-Taubadel, N., Frazier, B. C. & Lahr, M. M. The problem of assessing landmark error in geometric morphometrics: theory, methods, and modifications. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol.134, 24–35 (2007).

Dupej, J., Krajíček, V., Velemínská, J. & Pelikán, J. Statistical mesh shape analysis with nonlandmark nonrigid registration (2014).

Myronenko, A. Xubo Song. Point set registration: coherent point drift. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell.32, 2262–2275 (2010).

Krajíček, V., Dupej, J., Velemínská, J. & Pelikán, J. Morphometric analysis of mesh asymmetry. J. WSCG (2012).

Oldfield, R. C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia9, 97–113 (1971).

Ferrario, V. F., Sforza, C., Miani, A. & Serrao, G. A three-dimensional evaluation of human facial asymmetry. J. Anat.186 (Pt 1), 103–110 (1995).

Roosenboom, J. et al. SNPs Associated with testosterone levels influence human facial morphology. Front. Genet.9, 497 (2018).

Rogers, L. J. Manual bias, behavior, and cognition in common marmosets and other primates. In: Progress in Brain Research vol. 238 91–113 Elsevier, (2018).

Bigoni, L., Krajíček, V., Sládek, V., Velemínský, P. & Velemínská, J. Skull shape asymmetry and the socioeconomic structure of an early medieval central European society. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol.150, 349–364 (2013).

Kertesz, A., Black, S. E., Polk, M. & Howell, J. Cerebral asymmetries on magnetic resonance imaging. Cortex22, 117–127 (1986).

Rentería, M. E. & Cerebral Asymmetry A quantitative, multifactorial, and plastic brain phenotype. Twin Res. Hum. Genet.15, 401–413 (2012).

Launonen, A. M. et al. A longitudinal study of facial asymmetry in a normal birth cohort up to 6 years of age and the predisposing factors. Eur. J. Orthod.45, 396–407 (2023).

Hun, K. D., Park, K. R., Chung, K. J. & Kim, Y. H. The relationship between facial asymmetry and nasal septal deviation. J. Craniofac. Surg.26, 1273–1276 (2015).

Dane, Ş. et al. Relations among hand preference, craniofacial asymmetry, and ear advantage in young subjects. Percept. Mot. Skills95, 416–422 (2002).

Yorita, G. J., Melnick, M., Opitz, J. M. & Reynolds, J. F. Cleft lip and handedness: a study of laterality. Am. J. Med. Genet.31, 273–280 (1988).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank to all participants in the study and also to Mgr. Markéta Gregorová, Ph.D. for English proofread of the text and all her valuable comments. We also want to thank Charles University Grant Agency for financial support throughout project No. 372221.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Katarína Harnádková: Conceptualization, project administration, investigation, data processing, data analyses, data visualization, data interpretation, writing the original draft, text review and text editing. Jan Měšťák3: Conceptualization and application, consultations and data interpretation, text review. Ján Dupej: Methodology, data processing and analyses, data visualisation, data interpretation, text review and text editing. Lenka Kožejová Jaklová: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, data interpretation, text review and text editing. Karolina Kočandrlová: Methodology and data curation, visualization, data interpretation, text review and text editing. Alexander Morávek: Data processing and data analyses, data visualisation, data interpretation, text review and text editing. Jana Velemínská: Supervision, conceptualization, data interpretation, writing the original draft, text review and text editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Harnádková, K., Měšťák, J., Dupej, J. et al. The relationship between facial directional asymmetry, handedness, chewing side preference, and eyedness. Sci Rep 14, 23131 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73077-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73077-5

This article is cited by

-

Evaluation of Facial Asymmetry Determined by Linear Measurements According to Hand Preference and Gender

Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (2025)