Abstract

During the first postoperative days following minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion (MISJF), patients often report serious pain, which contributes to high utilization of painkillers and prevention of early mobilization. This prospective, double-blind randomized controlled trial investigates the effectiveness of intraoperative SIJ infiltration with bupivacaine 0.50% versus placebo (NaCl 0.9%) in 42 patients in reducing postoperative pain after MISJF. The primary outcome was difference in pain between bupivacaine and placebo groups, assessed as fixed factor in a linear mixed model. Secondary outcomes were opioid consumption, patient satisfaction, adverse events, and length of hospital stay. We found that SIJ infiltration with bupivacaine did not affect postoperative pain scores in comparison with placebo, neither as group-effect (p = 0.68), nor dependent on time (group*time: p = 0.87). None of the secondary outcome parameters were affected in the postoperative period in comparison with placebo, including opioid consumption (p = 0.81). To conclude, intra-articular infiltration of the SIJ with bupivacaine at the end of MISJF surgery is not effective in reducing postoperative pain. Hence, we do not recommend routine use of intraoperative SIJ infiltration with analgesia in MISJF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic low back pain is often caused by a dysfunctional sacroiliac joint (SIJ), but frequently overlooked, potentially due to difficult diagnosis and inadequate treatment options1,2. If pain allocated to SIJ is refractory to conservative treatment options, minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion (MISJF) is being considered3,4. This treatment option is supported by industry-sponsored studies reporting high satisfaction rates in MISJF-treated patients5. During MISJF, the SIJ is stabilized by percutaneously inserted implants6. The implants are inserted laterally through the gluteal musculature, and across the SIJ to achieve joint fusion. During the first postoperative days, patients often report pain in the operated area, and it is reasonable to assume that pain is induced upon loading this operated joint. This postoperative pain is difficult to manage adequately and prevents early mobilization7. This pain contributes to patients taking high doses of analgesics7,8,9. However, analgesics, especially opioids, can cause nausea and drowsiness, resulting in inability to mobilize adequately10. Combined, postoperative pain and nausea may extend hospitalization and cause negative experience of hospitalization11.

To reduce postoperative pain following MISJF, an intra-articular SIJ infiltration with analgesia at the end of the procedure is advocated. In several orthopedic procedures, for example total knee arthroplasty and spinal fusion surgery intraoperative infiltration of the wound bed results in decreased consumption of opioids, earlier mobilization and shorter hospitalization time12,13,14. However, the effects of such an infiltration in MISJF are unclear and have never been described. Infiltrating the SIJ only takes little extra operating time and a minimal amount of fluoroscopy screening time but may have significant impact on postoperative care.

The aim of this study is to determine whether intraoperative intra-articular analgesia with bupivacaine 0.50% is superior to placebo (intraoperative intra-articular infiltration of NaCl 0.9%) in reducing postoperative pain in patients after MISJF and to determine whether opioid use is reduced in the intervention group during the first 48 h after surgery.

Methods

Study design

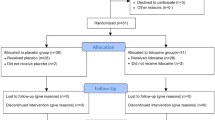

We conducted a prospective, double-blind, multi-center randomized controlled trial (blinding for the patient, clinician, and statistician) to investigate the effect of intraoperative SIJ infiltration with 1.5–5 cc bupivacaine 0.50% on postoperative pain after MISJF compared with 1.5–5 cc saline. Bupivacaine 0.50% was chosen for the intervention group because it is often used in diagnostic injections of the SIJ, with or without anti-inflammatory steroids, and it is effective in reducing pain in patients suffering from SIJ dysfunction15,16,17. Randomization was block-wise and stratified by center. This trial was registered at the Netherlands trial register (NL9151, 29/12/2022). The detailed study protocol has been published previously18. The study protocol was written in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 checklist of information to include when reporting a randomized trial19. This study has been approved by the Medical Ethical Committee (METCZ 20210069) at both participating centers (Zuyderland Medisch Centrum, Sittard-Geleen, and Medical Spectrum Twente, Enschede, both the Netherlands). The study was carried out in accordance with the protocol and with the principles enunciated in the current version of the Declaration of Helsinki, in accordance with the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) and the guidelines of Good Clinical Practice (GCP). All subjects were informed on the purpose of the study and gave written informed consent before participation.

Study population

Adult patients referred to two spinal orthopedic outpatient clinics eligible for primary MISJF surgery were potentially eligible to participate in this study. Indication for MISJF was considered by suspicion of SIJ pain based on medical interviewing, excluding other causes, and medical examination included provocative tests which had to evoke SIJ pain. In case of suspicion of SIJ dysfunction, diagnosis was confirmed by the gold standard image-guided intra-articular SIJ injection with local anesthetic according to the specific guideline. Patients were only eligible for MISJF if at least a 50% reduction of SIJ pain 30–60 min following image-guided injection occurred. Patients with previous ipsilateral surgery of any kind were not included in this study. Previous contralateral surgery of the SIJ was not an exclusion criterion.

Interventions

All patients were treated with MISJF using a series of triangular titanium, porous titanium plasma spray coated implants (iFuse Implant System®; SI-BONE, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Surgery was performed under general anaesthesia in prone position. Short-acting opioids like sufentanil or fentanyl were used during surgery. To prevent the influence of long-acting opioids on the postoperative pain and therefore obscuring the result of SIJ infiltration, no long-acting opioids were administered during or at the end of surgery. Depending on the local anatomy, two or preferably three triangular implants were placed across the SIJ with fluoroscopy, according to manufacturer’s instructions. After wound closure, a spinal needle was used to infiltrate the SIJ intra-articularly under fluoroscopic guidance. The distal part of the SIJ was visualized using fluoroscopy in anterior–posterior view applying lateral tilt as needed for optimization. Needle position was checked, and images were stored for potential review. Study medication, prepared by the pharmacist (bupivacaine 0.50% 1.5–5 cc (intervention) or NaCl 0.9% 1.5–5 cc (placebo)) was infiltrated. The physician administering the injection was blinded to the contents of the syringe. Both groups received the same perioperative protocol, including preoperative cefazolin, postoperative analgesia consisting of acetaminophen 4 times 1000 mg daily, standard physical therapy during hospitalization and deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis. Postoperatively, patients were transported to the recovery room, where they were monitored for a least one hour. During their stay at the recovery room and at the ward, patients received intravenous or intramuscular piritramide until the visual analogue scale (VAS) pain was ≤ 3. Dosage is determined based on visual analogue scale (VAS) pain score and body weight, 0.2–0.3 mg/kg with a maximum of 80 mg/day in four dosages.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was difference in pain, assessed using VAS between bupivacaine and placebo group during the first 48 h after surgery, with repeated post-infiltration measurements at recovery entry, recovery exit, and after 2, 4, 6, 24 and 48 h. Secondary outcome measures were opioid consumption, in which all opioid consumption is converted to morphine per os equivalent using a conversion table (Additional file 1), patient self-reported recovery using the General Surgery Recovery Index (GSRI) and VAS for satisfaction, leg and back pain, adverse events and length of hospital stay.19 Other study parameters are sex, age, BMI, preoperative opioid usage, occurrence of diabetes, causes of SIJ dysfunction, previous pelvic or back surgery, pre-operative pain and patients physical condition (ASA classification). The amount of fluid that the surgeon was able to infiltrate in the SIJ, duration of surgery, intraoperative blood loss and intraoperative opioid administration were monitored.

Statistical analysis

Difference in pain between SIJ infiltration with 1.5–5 cc bupivacaine 0.50% and placebo at around 2 h after infiltration is the primary endpoint and was used to calculate the sample size. Based on our own preliminary data, derived from recovery unit charts, we estimated that the standard deviation of the pain score is 2.2. A two-point difference on the eleven-points (0–10) pain score (SD 2.2) is considered clinically relevant20,21. In order to obtain this clinically meaningful effect with 80% power, 19 patients are required per group. Because no contrast is implemented during infiltration, there is an estimated chance of 10% that the infiltration will not be administered intra- but peri-articular. However, the analgesic effect of intra- and peri-articular infiltration is similar22,23. When taking into account a 10% loss to follow-up, 42 patients (21 patients per group) were enrolled in this study.

Frequency tables were provided for all categorical demographic information. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median ± interquartile range (IQR) depending on the distribution of the data. Analysis was performed by principal investigators using IBM SPSS statistical software package version 27 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Data was tested for normal distribution. When data was normally distributed a paired t-test was used to determine statistical difference between groups (e.g. pain score, cumulative opioid use). In case of absence for normal distribution, Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test was used. In addition, the group differences over time were determined using a linear mixed-effects model with group, time and the group-time interaction as fixed factors. Study center was included as random variable. Categorical data was assessed using Pearson’s Chi-Square test and Fisher’s exact test. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Patients’ characteristics are described in Table 1. A total of 42 patients were included in this RCT. One patient was excluded from analysis because intraoperative infiltration of study medication was unsuccessful. The remaining patients received the per protocol allocated treatment and received the full 5 cc of fluid infiltration. Twenty-two patients were analyzed to the bupivacaine group and nineteen patients to the placebo group.

Primary outcome measure

Intra-articular administration of bupivacaine did not affect postoperative pain scores in comparison with placebo, neither as group-effect (p = 0.68), nor dependent on time (group*time: p = 0.87). In Fig. 1 the pre- and postoperative pain scores are outlined for both study groups.

Secondary outcome measures

Bupivacaine did not affect opioid consumption at recovery or during the remaining 48 h postoperative period in comparison with placebo (p = 0.81) (Fig. 2). Patient reported recovery (GSRI), satisfaction and back and leg pain (VAS) at 24 h postoperatively did not differ between study groups (Table 2). There were also no differences in length of hospital stay or complications rates between bupivacaine and placebo group. The sole complication that occurred was one postoperative wound infection in the placebo group, which was resolved with antibiotic treatment.

Discussion

The most important finding of this study is that intraoperative SIJ infiltration with bupivacaine did not affect postoperative pain during the whole post operative period in comparison with placebo. The lacking effect of bupivacaine on pain is somewhat surprising, as it can affectively generate a diagnostic block. We hypothesize that the lack of pain response is due to postoperative pain following MISJF being mostly caused by iatrogenic injury to surrounding tissues and not the SIJ itself. This is supported by the theorem that the joint is fixed by three implants during surgery, directly limiting motion and perhaps pain. Thus, infiltrating the SIJ might be less effective than infiltrating the wound (soft tissue). Moreover, the latter has been deemed effective in other orthopedic procedures12,13,14. In this perspective, a study comparing analgesia with placebo for wound infiltration after MISJF might be interesting to conduct. Alternatively, part of the ineffectiveness of bupivacaine to influence postoperative pain might be due to the patient group itself. To elaborate, first, it is known that SIJ dysfunction is accompanied with diagnostic delay, hence patients often suffer from complaints for a long period of time before correct treatment is started. During the diagnostic trajectory often large amounts of pain killers are consumed, including opioids. The percentage of patients with SIJ dysfunction that consume opioids is around 40%9. Several studies have provided evidence for altered pain perception, known as opioid-induced hyperalgesia in people consuming opioids for an extended period24. Second, in recent literature it has become clear that pain catastrophizing is a predictor of pain severity among individuals with persistent musculoskeletal complaints. Pain catastrophizing is considered as a maladaptive coping strategy involving an exaggerated response to anticipated or actual pain25. Following spinal surgery around 20% of patients have persistent or recurrent pain in the back or limbs26. Moreover, patients that tend to catastrophize are more likely to have higher pain scores in the early postoperative period27,28. Patients with SIJ dysfunction that have an extended diagnostic trajectory, consume large amount of pain killers and report a low quality of life seem sensitive for psychological factors like pain catastrophizing29. Both altered pain perception and unfavorable psychological factors might have adversely influenced the effect of bupivacaine to reduce pain in the current study group.

In line with the primary outcome, perioperative administration of bupivacaine did also not affect secondary outcomes, such as postoperative opioid consumption. As expected, postoperative pain and opioid consumption are closely associated. Opioids are a standard component of pain management following spinal surgery, and their utilization should reflect the severity of postoperative pain. As can be seen in Fig. 2, opioid consumption in the first 48 h postoperatively is highly variable across patients. Patient-specific factors, such as individual pain thresholds and psychological factors, may influence opioid consumption. One can also expect there is a correlation between pre- and postoperative opioid consumption in patients undergoing MISJF. When a patient has been taking high doses of opioid consumption for a longer period, it is expected that this person will continue the need for opioids following MISJF30.

Lastly, while clinical outcomes such as other patient reported outcome measures (VAS recovery, satisfaction and back and leg pain), length of stay and complications showed descent results after MISJF, a surprising observation was the persistent pain after 48 h, comparable to preoperatively (Fig. 1). This is contrary to the typical expectation of pain decreasing over time postoperatively. We faced a challenge in verifying this observation since there was no available literature for comparison. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that most patients were discharged within the first day, suggesting pain was manageable, even though the pain scores remained consistently high during this period. Alternatively, patients may have sooner than expected reduced the use of pain medication, which would be a positive observation. Unfortunately, timing of pain medication was not observed detailed enough for substantiating this hypothesis.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study were the prospective, RCT-design in a multicenter setting, involving two high-volume MISJF centers in the Netherlands. This increases the generalizability of the results. A limitation in the presented study is that we did not apply intra-articular contrast. Therefore, it is uncertain whether the intraoperative infiltration was indeed intra-articular and not peri-articular. Though several studies have demonstrated that peri-articular infiltration of analgesia is as effective in reducing pain complaints arising from the SIJ as intra-articular infiltration, and therefore, we do not expect this uncertainty to relate to any bias in study outcomes23,31,32. It is conceivable that the act of SIJ puncture and saline irrigation itself contributes to pain reduction, independent of the analgesic effects of bupivacaine. This hypothesis merits attention in our conclusion, as it underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of pain management strategies in MISJF surgery. Lastly, the current study exclusively tracked postoperative morphine consumption, potentially leaving variations in the use of other analgesics, such as NSAID’s, unaccounted for among patients. This is also the case for and anti-emetics. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to presume that any disparities in this regard are mitigated due to the randomized design of the study.

Conclusion

Intra-articular infiltration of the SIJ with bupivacaine following MISJF surgery is not effective in reducing postoperative pain complaints, nor in reducing opioid consumption compared to placebo. While it is safe, we do not recommend routine use of intraoperative SIJ infiltration with analgesia in MISJF.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bernard, T. N. & Kirkaldy-Willis, W. H. Recognizing specific characteristics of nonspecific low back pain. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res.217, 266–280 (1987).

Sembrano, J. N. & Polly, D. W. How often is low back pain not coming from the back?. Spine (Phila Pa 1976)34, E27–E32 (2009).

Buchowski, J. M. et al. Functional and radiographic outcome of sacroiliac arthrodesis for the disorders of the sacroiliac joint. Spine J.5, 520–528 (2005).

Kibsgård, T. J., Røise, O. & Stuge, B. Pelvic joint fusion in patients with severe pelvic girdle pain—A prospective single-subject research design study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord.https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-85 (2014).

Martin, C. T., Haase, L., Lender, P. A. & Polly, D. W. Minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: The current evidence. Int. J. Spine Surg.14, S20–S29 (2020).

Tran, Z. V., Ivashchenko, A. & Brooks, L. Sacroiliac joint fusion methodology—minimally invasive compared to screw-type surgeries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Phys.1, 29–40 (2019).

Buchanan, P. et al. Best practices for postoperative management of posterior sacroiliac joint fusion. J. Pain Res.15, 1149–1162 (2022).

Bajwa, S. J. S. & Haldar, R. Pain management following spinal surgeries: An appraisal of the available options. J. Craniovertebr. Junction Spine6, 105–110 (2015).

Hermans, S. M. M. et al. Double-center observational study of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion for sacroiliac joint dysfunction: One-year results. J. Orthop. Surg. Res.https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-022-03466-x (2022).

Benyamin, R. et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Phys.11, S105–S120 (2008).

Gan, T. J. Poorly controlled postoperative pain: Prevalence, consequences, and prevention. J. Pain Res.10, 2287–2298 (2017).

Dysart, S. H., Barrington, J. W., Del Gaizo, D. J., Sodhi, N. & Mont, M. A. Local infiltration analgesia with liposomal bupivacaine improves early outcomes after total knee arthroplasty: 24-hour data from the PILLAR study. J. Arthroplasty34, 882–886 (2019).

Kim, H.-J. et al. Comparative study of the efficacy of transdermal buprenorphine patches and prolonged-release tramadol tablets for postoperative pain control after spinal fusion surgery: A prospective, randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. Eur. Spine J.26, 2961–2968 (2017).

Pace, V. et al. Wound infiltration with levobupivacaine, ketorolac, and adrenaline for postoperative pain control after spinal fusion surgery. Asian Spine J.15, 539–544 (2021).

Jung, M. W., Schellhas, K. & Johnson, B. Use of diagnostic injections to evaluate sacroiliac joint pain. Int. J. Spine Surg.14, S30–S34 (2020).

Kennedy, D. J. et al. Fluoroscopically guided diagnostic and therapeutic intra-articular sacroiliac joint injections: A systematic review. Pain Med.16, 1500–1518 (2015).

Scholten, P. M., Patel, S. I., Christos, P. J. & Singh, J. R. Short-term efficacy of sacroiliac joint corticosteroid injection based on arthrographic contrast patterns. PMR7, 385–391 (2015).

Hermans, S. M. M. et al. Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial on the effect of local analgesia for pain relief after minimal invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: The ARTEMIS study. BMJ Open11, e056204 (2021).

Moher, D., Schulz, K. F. & Altman, D. The CONSORT statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA285, 1987–1991 (2001).

Myles, P. S. et al. Measuring acute postoperative pain using the visual analog scale: The minimal clinically important difference and patient acceptable symptom state. Br. J. Anaesth.118, 424–429 (2017).

Salaffi, F., Stancati, A., Silvestri, C. & Ciapetti, A. Minimal clinically important changes in chronic musculoskeletal pain intensity measured on a NRS. Eur. J. Pain8, 283–291 (2004).

Cohen, S. P., Chen, Y. & Neufeld, N. J. Sacroiliac joint pain: A comprehensive review of epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Expert Rev. Neurother.13, 99–116 (2013).

Simopoulos, T. T. et al. Systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic effectiveness of sacroiliac joint interventions. Pain Phys.18(5), E713 (2015).

Pud, D., Cohen, D., Lawental, E. & Eisenberg, E. Opioids and abnormal pain perception: New evidence from a study of chronic opioid addicts and healthy subjects. Drug Alcohol Depend.82, 218–223 (2006).

Leung, L. Pain catastrophizing: An updated review. Indian J. Psychol. Med.34, 204–217 (2012).

Thomson, S. Failed back surgery syndrome—definition, epidemiology and demographics. Br. J. Pain7, 56–59 (2013).

Dunn, L. K. et al. Influence of catastrophizing, anxiety, and depression on in-hospital opioid consumption, pain, and quality of recovery after adult spine surgery. J. Neurosurg. Spine28, 119–126 (2018).

Papaioannou, M. et al. The role of catastrophizing in the prediction of postoperative pain. Pain Med.10, 1452–1459 (2009).

Cher, D. J. & Reckling, W. C. Quality of life in preoperative patients with sacroiliac joint dysfunction is at least as depressed as in other lumbar spinal conditions. Med. Devices8, 395–403 (2015).

Hah, J. M., Bateman, B. T., Ratliff, J., Curtin, C. & Sun, E. Chronic opioid use after surgery: Implications for perioperative management in the face of the opioid epidemic. Anesth. Analg.125, 1733–1740 (2017).

Hartung, W. et al. Ultrasound-guided sacroiliac joint injection in patients with established sacroiliitis: Precise IA injection verified by MRI scanning does not predict clinical outcome. Rheumatology49, 1479–1482 (2009).

Luukkainen, R. K., Wennerstrand, P. V., Kautiainen, H. H., Sanila, M. T. & Asikainen, E. L. Efficacy of periarticular corticosteroid treatment of the sacroiliac joint in non-spondylarthropathic patients with chronic low back pain in the region of the sacroiliac joint. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol.20(1), 52–54 (2002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M.M.H.: concept and design, writing and data collection. J.M.N.: concept and design, critical revision, supervision. R.J.H.K.: concept and design, writing. H.v.S.: critical revision, supervision. R.D.: writing and data collection. JM: statistical analyses, supervision, prepared figures 1 and 2. M.K.R.: concept and design, data analysis. D.M.N.H.: concept and design. J.W.P.: concept and design. K.L.L.M.: concept and design. I.C.: critical revision, supervision. W.v.H.: concept and design, critical revision, supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hermans, S.M.M., Nellensteijn, J.M., Knoef, R. et al. Effectiveness of intra-articular analgesia in reducing postoperative pain after minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 14, 22647 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73638-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73638-8