Abstract

Agreeableness, one of the five personality traits, is associated with socio-cognitive abilities. This study investigates how agreeableness impacts the perception of social interactions, while considering sex that might moderate this effect. Sixty-two young adults, preselected to ensure a wide range of agreeableness scores, underwent EEG recording while viewing images depicting real-world scenes of two people either engaged in a social interaction or acting independently. Behavioral results suggested a trend where higher agreeableness scores predicted better ability to detect social interactions primarily in males. ERP analysis showed that individuals with higher agreeableness exhibited stronger neural differentiation between social and non-social stimuli, observed in both females and males, and in the whole sample. This neural differentiation, occurring early in the processing timeline, was particularly extensive in males, and predictive of their performance. Three independent source analyses, conducted for the whole sample and for each sex, identified the engagement of right fronto-parietal regions for the ERP-agreeableness association. These findings enhance our understanding of how agreeableness shapes the neural mechanisms underlying social interaction detection and emphasize sex as an important factor in this dynamic. They also highlight the need for tailored approaches that consider personality traits and sex in clinical interventions targeting social impairments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Agreeableness is one of the five personality traits defined by the Five factor model1 which has been associated with socio-cognitive abilities including empathy and theory of mind (ToM)2. Like all personality traits, agreeableness is characterized by two extreme poles and each person positions herself between them depending on her own individuality. Individuals high in agreeableness tend to be altruistic, cooperative, and understanding of others’ perspectives. In contrast, those low in agreeableness may exhibit poorer social skills, self-focus, and even aggression in extreme cases2,3. Neuroimaging studies have strengthened the association between agreeableness and social cognition by showing an overlap of their neural networks4,5. In our previous fMRI study6, we investigated how neural variations during social content encoding are related to differences in agreeableness. Specifically, by using a classic ToM task, in which social and socially neutral animations were shown7, we observed a significant relationship between the similarity in neural representations for the two types of content and the levels of agreeableness. We found that individuals with lower agreeableness showed more similar neural patterns for social and neutral content, while those with higher agreeableness showed more distinct patterns, specifically in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), a brain region typically associated with ToM abilities8,9,10,11. This finding suggests that individual differences in agreeableness are associated with differences in social information processing. However, in the task adopted, where participants infer others’ mental states, the social information processed by the brain was complex, characterized by several psychological dimensions, including affective aspects12, which we could not disentangle.

To overcome this limitation, in the present study we isolated the social dimension by focusing on the detection of social interactions, a pivotal aspect of social information processing, leaving the investigation of the emotional dimension to another study13. Social relationships are vital for our survival and well-being, as evidenced during periods of lockdown when enforced isolation and limited social interactions had a significant impact on mental health, leading to increased symptoms of anxiety and depression14,15. Here, the social interaction construct was operationalized as a relational process of two individuals acting while looking at each other (i.e., “mutual gaze”) or by looking at the same object/point of interest (i.e., “joint attention”), as in the MEG study by Isik and colleagues16. These two types of interactions are among the first to be identified by infants17,18 and, as such, are considered the bases of social engagement. Indeed, given their relevance for survival, stimuli depicting social interactions enjoy privileged access to visual processing and awareness, aiding the brain in information extraction16,19,20. Building upon the dual-processing account in social cognition21,22, this rapid processing likely involves the automatic cognitive system, which enables quick detection of essential social signals, such as mutual gaze or joint attention, crucial for social bonding and interaction. However, beyond this immediate, automatic detection, the controlled system may further refine and interpret these social cues, especially in more complex or ambiguous scenarios. This dual engagement (i.e., automatic and controlled processes) enables individuals not only to recognize social interactions but also to evaluate them, both of which could be influenced by personality traits such as agreeableness.

To empirically test this hypothesis, we employed electroencephalography (EEG) to capture the temporal dynamics of neural activity during social interaction detection tasks. EEG allows for precise temporal resolution, enabling us to discern whether agreeableness influences early perceptual and attentional stages or later, more inferential processing stages of social information handling. Specifically, we predict that individuals higher in agreeableness will demonstrate heightened neural responsiveness during the initial, automatic detection of social interactions, as evidenced by earlier ERP components. Additionally, we anticipate that these individuals will also show more distinct processing during the later, controlled evaluation stage, reflected in modulations of later ERP components. Conversely, individuals lower in agreeableness may exhibit less differentiation between social and non-social stimuli during these stages, reflecting a reduced sensitivity to the social cues in the environment.

Furthermore, considering evidence from the empathizing-systemizing theory23 and existing literature on sex differences in social cognition24,25,26,27,28, we anticipate that sex may impact social processing in a way that could moderate the influence of agreeableness. Females, who generally exhibit heightened social sensitivity, may show amplified neural responses to social interactions by default, potentially rendering the agreeableness trait less influential in this domain. In other words, because females already demonstrate superior detection and processing of social and emotional stimuli24,25, as well as heightened responsivity within the action observation network26, the neural correlates associated with social interaction detection might not vary significantly with levels of agreeableness in females. This could result in more consistent ERP patterns across females, irrespective of individual differences in agreeableness. In contrast, males may show more variability in their neural responses to social interactions based on their agreeableness levels. Moreover, it is well-established that females tend to score higher in agreeableness than males on average1,2. To avoid this potential bias and to explore the impact of agreeableness on social processes in a balanced way across females and males, we specifically selected our sample to ensure there were no significant sex differences in agreeableness. However, it is important to note that the literature presents mixed findings on this topic, with some studies showing inconsistent behavioral differences depending on the specific task or process under investigation27,28. Additionally, neuroanatomical29 and neurobiological factors for a review 30,31: are known to contribute to sex differences in social cognition, further complicating this interaction. Thus, while sex is a crucial factor to consider in this research, the exact nature of its interaction with personality traits like agreeableness requires careful examination.

To examine individual differences in ERP responses, we opted for a massive univariate approach by using an EEGLAB plugin (i.e., LIMO toolbox) that allowed us to analyse and explain variance by considering both intra- and inter-subject variability, as well as the effect of the experimental condition 32. We considered this method to be less restrictive and reductive compared to traditional approaches, as it does not require a priori selection of specific time points, electrodes, or components to analyze, which is more suitable when there is limited existing literature on the processes being investigated, as in our case. Moreover, considering the limited spatial resolution of EEG, we performed source estimation to delve deeper into the exploration of the neural processes at play and gain a more comprehensive understanding of the role that agreeableness may have in shaping these processes.

Methods

Participants recruitment and personality assessment

Sixty-two young adults (27 males) with a mean age of 24.03 (SD = 4.34, range = 18–35 years) were selected from a larger sample (N = 462) based on their agreeableness scores to increase variability within the study: 22 participants had scores below, and 20 above 1.4 standard deviations from the Italian population mean, while the remaining 20 had scores around the average. As personality traits are continuous variables, in order to ensure that our sample accurately captures measurements at either tail of the distribution, deliberate efforts were made to select individuals with diverse scores along the z-score continuum, encompassing both negative and positive values. This sampling strategy increases the power to detect moderate effect sizes in small samples, without inflating the false positive rate33. The selection process also considered the chronological order of responses, thus, when several individuals had the same score, priority was given to the first respondent. Additionally, efforts were made to ensure a balanced representation of males and females in the final sample.

The screening process involved administering the Italian adaptation of the Big Five Inventory (BFI) online34, a widely-recognized questionnaire in which participants indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with statements about their attitudes. The questionnaire comprises 44 items rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), assessing the five personality traits from the Five factor model (Extraversion, Neuroticism, Openness, Conscientiousness, Agreeableness). The BFI has a test–retest reliability ranging from 0.788 to 0.96634. The questionnaire was advertised through different social media and email.

Participants were asked about their handedness before completing the BFI, resulting in a total of six left-handed subjects (three males and three females) with the remaining participants being right-handed. None of the participants reported a history of neurological or psychiatric disorders as assessed through specific questions administered before the questionnaire. They all provided written informed consent and received 20 euros for their participation. The study and informed consent procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the SISSA’s ethics committee (approval number: 24577-III/13).

The procedure involved first sharing an online Google Form that included demographic questions and the BFI. After collecting all responses, participants were selected based on their agreeableness scores, as described above. The selected participants were then invited to the laboratory, where they completed the social interaction perception task while undergoing EEG recording.

Social interaction perception task

Participants viewed 48 visually matched target images depicting real-world scenes showing two people either engaged in a social interaction or acting independently (24 stimuli per condition, namely social and non-social). Participants indicated whether each target image represented a social interaction by pressing a key button. The operational definition of social interaction aligned with Isik and colleagues16, who originally developed the stimuli: two agents with actions directed towards each other (mutual gaze) or a shared point of interest (joint attention).

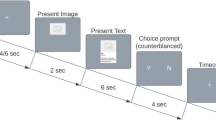

Participants were seated 60 cm away from the screen in a dark and quiet room. Stimuli were presented at 9 × 5 degrees of visual angle on a gray background, in the center of the screen by using PsychoPy3 (v2020.1.1). The task began with an explanation of the definition of social interaction using 4 example images and 4 practice trials that were not included in the analyses. Participants completed 240 trials (120 per condition) interspersed with a self-paced pause every 60 trials. Stimuli were arranged in a pseudo-random order to avoid more than two repetitions of the same condition. Each trial began with a fixation cross (1000 ms), followed by the target image (500 ms) (Fig. 1); after the target offset, a blank screen was shown (2000 ms) after which they had a maximum of 2000 ms to indicate their response by pressing either the “f” or “j” key on a QWERTY keyboard using the index fingers of both hands. The response keys were counterbalanced across participants.

Social perception interaction task. (a) Schematic representation of the task; stimuli succession is represented left to right, with the respective screen presentation time expressed in milliseconds below each stimulus. The image is one of the targets used representing social interaction. (b) Examples of stimuli depicting social interactions (on the top), and stimuli depicting independent actions (at the bottom).

Behavioral data analysis

We collected accuracy and reaction time (RT) data. RTs were filtered to exclude errors, anticipated responses (< 150 ms), and outliers exceeding 3 standard deviations from the subject’s mean for each condition. Signal detection theory indices were computed for accuracy measures. The sensitivity index (dʹ) was used to quantify the participant’s ability to discriminate social from non-social stimuli. The formula for calculating dʹ is: dʹ = ZHIT − ZFA, where Hit represents the proportion of social trials to which subjects responded “social” (hit rate) and FA represents the proportion of non-social trials to which subjects responded “social” (false-alarm rate). Both rates were Z-transformed. We also calculated the bias for social responses, indicating the subject’s tendency to respond “social”, using the formula: − 0.5*(ZHIT + ZFA) 35,36.

Next, we performed a linear mixed-effects models analysis by means of the nlme package in R v.4.1.137 to examine the impact of agreeableness on participants’ sensitivity to differentiate social from non-social stimuli. The sensitivity index (dʹ) was used as the dependent variable, agreeableness was included as a fixed effect, and subject intercepts were considered as random effects. A second model was created to investigate whether the relationship between agreeableness and sensitivity differed between males and females, by adding sex as an additional fixed effect. The same analyses were repeated for the bias measure, examining the presence of a potential bias toward social responses. We also checked for sex differences in agreeableness scores by means of an independent t-test. To ensure that any observed effects were specific to agreeableness and not influenced by other personality traits, the other four traits were then included as additional predictors in the models. Assumptions of linearity, homoscedasticity, and normality were assessed by inspecting residual plots.

EEG recording and preprocessing

EEG data was collected using a cap with 64 Ag/AgCl active electrodes based on the International 10–20 system38. A BioSemi Active-Two amplifier system was used for signal amplification. The ActiView acquisition software (version 707, Biosemi, Amsterdam) was employed for data visualization and storage. Electrode offsets were maintained within ± 50 mV, and the signal was sampled at a rate of 1024 Hz with a 24-bit digitization resolution. Eye movements and blinks were monitored using horizontal and vertical electrooculogram (EOG) recorded from additional electrodes placed below and above the left eye. The stimulus onset was synchronized with the Biosemi recordings by sending triggers from the experimental task in PsychoPy via the parallel port to the EEG apparatus. These triggers allowed us to mark the timestamps for the stimuli and differentiate between social and non-social stimuli.

Data were pre-processed offline in EEGLAB 14.1.1b (https://sccn.ucsd.edu/eeglab)39, in Matlab R2021a (https://uk.mathworks.com/products/matlab.html). Continuous EEG recordings were resampled offline at 250 Hz, and band-pass filtered (cut-off frequencies: 0.25 and 45 Hz) using two zero-phase Hamming windowed sinc FIR filters (transition bandwidth: 0.5 and 10 Hz, passband edges: 0.5 and 40 Hz). Bad channels, poorly correlated with the others, were removed thorough an EEGLAB clean_rawdata plugin (autocorrelation parameter = 0.8, excluding on average 1.9 channels, SD = 2.1). Epochs ranging from 1000 ms before and 2500 ms after the stimulus onset were then extracted. An independent component analysis (ICA)40 was performed to remove those components with more than 60% probability of being eye, motor, channel noise, heart, or line noise using ICLabel41. On average, 18% of components per subject were removed.

After the ICA, removed channels were replaced using spherical spline interpolation42 and data were re-referenced to a common average reference. Finally, all epochs were corrected to a pre-stimulus baseline of 200 ms and were inspected for artifacts based on different43. Specifically, artifact rejection followed the subsequent criteria: (a) ± 125 µV for the standard extreme values thresholding; (b) current drifts larger than ± 50 µV/epoch and R2 > 0.3 for the linear trend test; (c) SD > 7 (for each channel) and SD > 3 (for all channels) for the improbability test; and (d) SD > 7 (for each channel) and SD > 3 (for all channels) for the kurtosis test. Epochs including data points exceeding any of these criteria were excluded from further analyses. Overall, 9.7% percent of the trials were rejected (with no asymmetry across conditions). The average number of epochs used for the analysis in both conditions was 108, ranging from 66 to 115 epochs. Two participants (one male and one female) were excluded from the EEG analysis due to technical problems during the recording.

ERP analysis

ERP analysis was performed using Matlab R2021a along with EEGLAB 2020_0 and LIMO EEG plugin (v 2.0, https://github.com/LIMO-EEG-Toolbox/limo_tools) that allows for performing robust statistics, handling non-normal data and outliers. A massive univariate approach was used by running two levels of analysis44.

First-level GLM analysis

At the first level, parameters of a General Linear Model were estimated by using a standard ordinary least squares solution for each subject, at each time point and each electrode independently, and separately for the two experimental conditions, namely social and non-social. To assess the differential activity evoked by the two conditions, the corresponding ERP amplitudes were subtracted to create a contrast. The considered time window ranged from 0 to 1000 ms, time locked to stimulus onset. To maintain higher inter-individual variability, erroneous trials were not excluded from the model, since we expected accuracy to vary in relation to agreeableness scores.

Second level GLM analysis

At the group level, a robust regression analysis was conducted on the contrasts between social and non-social ERP responses, using agreeableness as a regressor. The same analysis was repeated separately for males and females to explore whether similar neural effects emerge across males and females. An additional robust regression was performed for the same ERP contrasts and dʹ within the time windows in which we observed a significant effect of agreeableness, to investigate whether the effects associated with agreeableness might be predictive of task performance.

All reported results underwent correction for multiple comparisons. Specifically, we used a spatial–temporal clustering with a cluster forming threshold of p = 0.0545,46.

Source analysis

Cortical source activations were estimated using the Brainstorm software, which employs a distributed dipoles model for fitting47. The locations of the scalp-recorded electrical activity were estimated using the dynamic statistical parametric mapping (dSPM) method48, which uses minimum-norm inverse maps. Single subject noise covariance matrices and individual noise standard deviations at each location were calculated and estimated by means of the pre-stimulus baseline intervals (− 100 to − 2 ms) from single trials49.

For the head model, the OpenMEEG algorithm, which employs the symmetric Boundary Element Method (BEM) as the forward model was employed with the default parameters in Brainstorm, using the ICBM152 anatomy since individual anatomies were not available. The BEM model provides three realistic layers and representative anatomical information50,51. The source estimation was performed using the option of constrained dipole orientations, which models one dipole oriented perpendicular to the cortical surface for each vertex47.

For the estimation of active sources, the single-trial EEG data for each participant were averaged to obtain the subject average. Sources were then separately estimated for the two experimental conditions (social and non-social) and subtracted to create a contrast at the subject level. On each source, we applied a z-score normalization against the baseline period to reduce the influence of inter-individual fluctuations in neural current intensity caused by non-relevant anatomical or physiological differences and rectified them in absolute values. To investigate the cortical sources underlying the ERP effects associated with agreeableness, the cortex surface was divided into 50 non-overlapping regions using the surface clustering option in Brainstorm. We chose to adopt a whole-brain parcellation approach, which provides a suitable compromise between the limited ROI-based method and the overly corrected whole-brain approach.

After extracting the contrast values from the 50 regions within the time window of the ERP-agreeableness significant effect, a robust correlation analysis was conducted between these contrast values and agreeableness scores. The correlation analysis was performed for the entire sample and separately for females and males. A skipped Pearson correlation52 was performed by means of the Robust Correlation toolbox (https://github.com/CPernet/Robust-Correlations)32, which considers the overall structure of the data to protect against bivariate outliers. Statistical significance was assessed using percentile bootstrap 95% confidence intervals, with results adjusted for multiple comparisons through the FDR correction (p = 0.05).

Results

Behavioral results

Accuracy results are reported in the Supplementary material (Tables 1 and 2). The linear mixed-effects model examining the relationship between agreeableness and the ability to discriminate between social and non-social stimuli, as measured by the dʹ index, did not yield a significant effect (F(1, 60) = 0.29, p = 0.59, η2 = 0.004). When sex was included as an additional fixed effect in the model, a trend emerged showing that higher agreeableness scores predicted better ability to detect social interactions differently across males and females, with more agreeable males being more sensitive, although the p value did not reach the significance (F(1, 58) = 3.62, p = 0.062, η2 = 0.06; Fig. 2).

Scatterplot showing the relationship between agreeableness and the dʹ measure. Agreeableness is represented in z scores, the red line represents females, the blue line males; each spot is a subject. The grey shadow around the trendline represents the standard error (statistics and p values are reported in the text).

An independent t-test was carried out to check whether the abovementioned results might be affected by differences in the level of agreeableness between males and females and no significant difference emerged (t = 0.075, p = 0.94), indicating a well-balanced sample in terms of agreeableness. Finally, no differences were found between males and females in terms of agreeableness-related modulations of the response bias measure for social responses (F(1, 58) = 0.59, p = 0.44, η2 = 0.01). No significant or nearly significant associations with any of the dependent behavioral variables investigated were observed for any of the other personality traits in either model, with or without considering sex (all p’s > 0.1).

Visual inspection of residual plots did not reveal any obvious deviations from linearity, homoscedasticity or normality.

ERP results

Overall sample analysis

We first examined the entire sample to investigate the correlation between agreeableness and the ERP social—non-social contrast. We identified two significant clusters:1) Cluster 1: 191–227 ms (max F value 13.41 at 215 ms on channel P10, corrected p value 0.045); 2) Cluster 2: 199–223 ms (max F value 9.82 at 211 ms on channel C3, corrected p value 0.003); (Fig. 3a). These results indicate that higher agreeableness is associated with more negative contrast values over the left fronto-central electrodes and, as a consequence of the dipole effect, more positive contrast values over the right parietal electrodes (Fig. 3b). In contrast, low agreeableness was linked to the opposite pattern. To inspect more carefully the direction of these contrasts, we divided the sample into two groups based on a median split of their agreeableness z-scores (high agreeableness, i.e., high A: N = 28, 12 males; low agreeableness, i.e., low A: N = 32, 14 males). We then plotted their averaged ERPs (i.e., first level beta values) for both social and non-social conditions (Fig. 3c). The plot revealed that the high A group exhibited a larger negative amplitude for social versus non-social trials over the left fronto-central electrodes, whereas the low A group showed a greater negativity for the non-social stimuli. The reverse pattern, was observed over the right parietal electrodes reflecting a greater positivity for non-social versus social trials in the low A group.

ERP-Agreeableness regression results for the entire sample. (a) Raster plot depicting significant channels and time-points for the agreeableness regression colored based on their F values. On the right the topographical representation of the F values averaged across the significant time-window (191–227 ms) highlighting the scalp regions where significant effects were observed; the larger black circles on the topographic plot represent the electrodes that formed the significant clusters. (b) Scatterplots representing the correlation between the beta contrast values averaged across the significant time window and the agreeableness trait, separately for the two clusters. (c) Trace plots showing the mean beta values for the social (in blue) and non-social conditions (in orange) averaged over the significant electrodes from each of the two clusters, separately for the high A and low A group.

Female sample analysis

Next, we focused on the female participants to determine if similar patterns emerged. A significant cluster was found ranging from 195 to 227 ms (max F value 19.03 at 199 ms on channel CP6, corrected p value 0.011; Fig. 4a). This cluster overlapped with Cluster 1 from the entire sample. In this cluster, more agreeable females showed more positive contrast values, reflecting a larger positive amplitude for social versus non-social trials over the right centro-parietal electrodes. Conversely, less agreeable females showed more negative contrast values, indexing a larger positive amplitude for non-social versus social trials (Fig. 4b,c).

ERP-Agreeableness regression results for the female sample. (a) Raster plot depicting significant channels and time-points for the agreeableness regression colored based on their F values. On the right the topographical representation of the F values averaged across the significant time-window (195–227 ms). (b) Scatterplot representing the correlation between the beta contrast values averaged across the significant time window and the agreeableness trait. (c) Trace plots showing the mean beta values for the social (in blue) and non-social conditions (in orange) averaged over the significant electrodes, separately for the high A and low A group.

Male sample analysis

Within the male sample, three significant clusters were found across three different time windows: 1) Cluster 1:140–160 ms (max F value 15.58 at 152 ms on channel C3, corrected p value 0.008); 2) Cluster 2: 367–391 ms (max F value 11.78 at 383 ms on channel TP8, corrected p value 0.015); 3) Cluster 3: 703–730 ms (max F value 12.03 at 723 ms on channel FC2, corrected p value 0.006); (Fig. 5a). In Cluster 1, males with higher levels of agreeableness showed more positive contrast values over the left central electrodes (Fig. 5b). This was driven by a larger positive amplitude for social versus non-social trials in more agreeable males, while less agreeable males displayed a greater positivity for non-social stimuli (Fig. 5c).

ERP-Agreeableness regression results for the male sample. (a) Raster plot depicting significant channels and time-points for the agreeableness regression colored based on their F values. On the right the topographical representation of the F values averaged across the significant time-windows in the three clusters. (b) Scatterplots representing the correlation between the beta contrast values averaged across the significant time window and the agreeableness trait, separately for the three clusters. (c) Trace plots showing the mean beta values for the social (in blue) and non-social conditions (in orange) averaged over the significant electrodes from each of the three clusters, separately for the high A and low A group.

Within Clusters 2 and 3, the correlation pattern between agreeableness and the ERP social—non-social contrast values was consistent with the findings from the entire and the female samples. Higher agreeableness was associated with more positive contrast values over the right temporo-parietal electrodes (Cluster 2) and more negative contrast values over the left fronto-central ones (Cluster 3) (Fig. 5b). These contrasts reflected greater positivity (Cluster 1) and negativity (Cluster 2) for social trials in highly agreeable male participants, and for non-social trials in male participants with low agreeableness (Fig. 5c).

Task performance correlation analysis

Lastly, we conducted regression analyses to determine if the observed ERP effects for agreeableness predicted also task performance. A significant positive correlation was found within the male sample between the dʹ measure and the ERP social—non-social contrast values within Cluster 1 (140–160 ms, max F value 29.91 at 141 ms on channel P1, corrected p value < 0.001). This correlation mirrored the relationship with agreeableness: higher dʹ scores were associated with more positive ERP contrast values (Fig. 6), reflecting a larger ERP amplitude for social versus non-social stimuli.

Source localization

Overall sample analysis

We first examined the entire sample to investigate the relationship between agreeableness and the activation for the social—non-social contrast. A significant positive correlation was identified in the right fronto-parietal cortex (rFPC; r = 0.35, corrected p = 0.05; Fig. 7a,b) within the averaged time window of the ERP effect (191–227 ms). The source activation in the rFPC was greater for social versus non-social stimuli in more agreeable subjects, which mirrors the association found with the right parietal ERP component.

Female sample analysis

We then analyzed the female sample to determine if a similar correlation existed. A positive correlation was indeed observed in the rFPC within the averaged time window of the female-specific ERP effect (195–227 ms, r = 0.43, uncorrected p = 0.017, corrected p = 0.42; Fig. 7c). However, this result did not survive the FDR multiple comparison correction, indicating that the finding should be interpreted with caution.

Male sample analysis

For the male sample, a significant positive correlation emerged in the same parcel (rFPC; r = 0.52, corrected p = 0.05; Fig. 7d), within the time window corresponding to the second ERP cluster (367–391 ms). This result reflects a greater rPFC activation for social versus non-social stimuli in more agreeable males. No significant correlations were observed in other parcels for the time windows corresponding to the first and third ERP cluster after correcting for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

This study investigated the influence of the personality trait agreeableness on the neural processing of social interactions. Agreeableness is one of the five broad dimensions of personality provided by the Five factor model, mainly associated with social cognitive processes1,2, as confirmed by recent neuroimaging studies evidencing an overlapping neural network between these two domains4,5. Our previous fMRI study6, showed that individuals with higher agreeableness exhibit more distinct encoding of social and non-social information, particularly in the dmPFC, a brain region linked with ToM abilities8,9,10,11. In this study, we focused on how agreeableness affects the detection of social interactions and at what stage of neural processing this occurs.

At the behavioral level, individuals with higher agreeableness scores showed a tendency toward a better discrimination of social from non-social interactions. Although this trend did not reach statistical significance, it is noteworthy that the direction of the effect aligned with our hypothesis that higher agreeableness is associated with greater sensitivity to social stimuli. This observation suggests that agreeableness may play a role in shaping how individuals engage with social information, even if this effect was subtle and seemed to vary across males and females.

In terms of neural responses, we found that agreeableness was associated with differential ERP signals during the processing of social versus non-social stimuli. These effects were evident both in early time windows (for the entire sample and females ~ 200 ms, for males ~ 150 ms), and later time windows in males (~ 380 ms, ~ 720 ms), indicating that agreeableness may influence multiple stages of cognitive engagement with social content. Importantly, the association between agreeableness and the neural electrical activity across all our results pointed in the same direction: more agreeable participants showed an increased responsivity to social compared with non-social stimuli, whereas less agreeable participants exhibited the opposite pattern. These findings are in line with previous research demonstrating that social stimuli elicit larger ERP amplitudes compared to socially neutral stimuli53,54, with this effect being smaller in populations with lower social skills, such as ASD patients55,56. According to the well-regarded social motivation theory, in this population, reduced ERP amplitudes may reflect shallow processing due to hyposensitivity in neural systems supporting motivation and attention to social stimuli57,58,59. As established in the literature, social stimuli are prioritized in the human brain16,60,61, likely due to their rewarding nature and relevance for survival54,62. Thus, larger ERP amplitudes during early time windows may reflect the allocation of greater cognitive resources to process social stimuli, driven by a natural predisposition to prioritize social information57,60,63. In contrast, this processing priority appears diminished in ASD, potentially due to a lower perceived rewarding value of social stimuli57, often resulting in greater ERP responses to neutral stimuli55. Interestingly, we observed a similar pattern in individuals with lower agreeableness, where higher neural responses were found for stimuli depicting non-social interactions suggesting that the typical preference for social stimuli is not operating as expected. Since social preference has been argued to be a predictor of attention orienting60, the attentional resources may be redirected to other stimuli such as objects57,63.

It is important to note that while this pattern resembles that observed in ASD, we are drawing a parallel between these neural responses rather than suggesting a direct equivalence. Noteworthy, in this study, participants were drawn from the general population without any specific deficit that could directly affect their social processing abilities. This may partially explain the relatively weak modulation of agreeableness on the sensitivity scores measured behaviorally. At the same time, agreeableness may still influence motivational and attentional processes related to social stimuli, even without affecting the ability to distinguish between social and non-social interactions. Indeed, increased ERP amplitudes observed during early time windows suggest the engagement of attentional mechanisms during the initial processing of stimuli, associated with the saliency and relevance of the same53,64,65,66,67. Consequently, we argue that agreeableness can exert a modulatory influence on these processes by enhancing the focus on social stimuli. On the other hand, individuals with low agreeableness may exhibit reduced processing of social stimuli that convey information about social interactions. This could be attributed to a lower processing priority placed on social content, leading to a greater orientation towards non-social stimuli. It could be argued that for less agreeable individuals, the reduced salience and relevance of social stimuli may yield these stimuli less engaging, thereby increasing the likelihood of distraction and mind wandering (MW) in this context (see68 for a review). Although these individuals might focus on non-social elements, their overall disengagement from the social context could make them more prone to MW during the task. However, the rapid pace of the task and the brief duration of stimulus presentation likely reduce the occurrence of sustained MW, though brief and intermittent episodes may still occur, particularly between trials. This hypothesis considering the role of personality in MW and its impact on brain social processing, warrants further investigation in future studies.

Considering the extant literature about ERP neural components associated with late latencies67,69,70, our findings suggest that agreeableness not only affects the initial salience and relevance during the processing of social stimuli but may also play a role in more complex attentional processes related to the rewarding aspects of these stimuli. The early ERP effects observed in the ~ 200 ms time window, suggest that agreeableness modulates rapid, automatic processing stages that prioritize social information. Furthermore, the later ERP effects, around ~ 380 ms and ~ 720 ms, suggest that agreeableness continues to influence more prolonged and integrative cognitive processes, potentially reflecting deeper engagement with socially relevant content. Interestingly, these later effects were not as prominent in females, suggesting that their motivational processes may be less influenced by personality traits such as agreeableness. This interpretation aligns with the findings from our related study on agreeableness and emotional states decoding, where we observed a more extensive effect of agreeableness in males compared to females13. This can be understood in the context of existing research on sex differences, which has shown that females tend to be more socially oriented71, more sensitive to non-verbal social and emotional cues, and quick learners of such cues compared to males30,31. Some electrophysiological studies have shown a greater ERP neural response in females associated with social stimuli as opposed to objects31. Even when it comes specifically to social interaction, females have been found to anticipate social interactions by predicting the actions of people whereas males need to acquire more information28. These inherent sex differences may contribute to the lesser impact of personality on social interaction detection processes in women. Overall, our results suggest that sex is an important factor to consider when trying to understand the neural underpinnings of inter-individual differences in personality traits.

The source estimation procedures identified the right fronto-parietal area as a potential brain region underlying the association between agreeableness and the social – non-social ERP effects. Specifically, highly agreeable individuals exhibited a stronger activation of this brain region in response to social stimuli compared to non-social stimuli. This brain regions represent a pivotal hub of the dorsal attention network, which is responsible for selecting relevant sensory information by amplifying relevant input and suppressing irrelevant input72 therefore supporting our interpretation about the association between agreeableness and motivational and attentional processes. However, this proposed explanation should be taken with caution since for the sources’ estimations, individual anatomies were not available. Noteworthy, Wilkowski and colleagues73 found an association between agreeableness and attention to social stimuli at the behavioral level; our findings broaden this evidence by adding the neural component.

Our study aimed at integrating models of social cognition with the Five Factor personality framework while also considering the mediating role of biological factors, such as sex, to create a cohesive narrative. Our findings contribute to this integrative process as they allow to account for the influence of individual differences which to date have been poorly investigated. Building on our current findings as well as similar results from our study on emotional states decoding13, we suggest a model that encompasses personality, specifically agreeableness, and its modulatory influence on higher order mental processes for decoding social and emotional cues such as the detection of social interactions and the decoding of complex emotional states. However, in the present study, the impact of biological factors, particularly sex, is less clear, since at the neural level the interaction between sex and agreeableness was not directly tested. Future studies should address this gap to better clarify the role of sex in the proposed model.

With our study we certainly provide valuable insights into the domains of personality and social cognition, however we acknowledge some limitations that influence the interpretation and generalizability of our findings. First, because our results lack direct comparisons in the current literature, the proposed model is necessarily preliminary and requires validation through subsequent research. This validation could involve comparing healthy individuals with those with ASD and investigating the role that personality might play in this special population. Furthermore, future research could benefit from examining how EEG microstates74 differ between social and non-social conditions and how these differences relate to agreeableness. Such an approach could offer additional insights into the temporal organization of brain activity providing complementary information to our current findings, particularly in understanding the stability and transitions of brain states in relation to social cognition and personality traits. Another limitation is that the observed association between agreeableness and neural activity at a stage of processing implicated in attention does not establish a causal relationship. Our suggestion of a modulation effect of agreeableness on attentive neural processes involved in social interaction detection, based on the aforementioned literature, extends beyond the direct evidence offered by our data.

Additionally, the disparity between behavioral and neural findings poses a challenge to the interpretation of our results. Behavioral measures can be influenced by a wide range of factors, and may not always detect subtle neural differences among healthy subjects. The adoption of a binary yes/no response format in our task may have further restricted the detection of variability in participants’ responses, contributing to the observed inconsistency between behavioral and neural data. Future studies might consider employing more nuanced behavioral measures that can better capture individual differences in social interaction processing.

Conclusion

The current study expands our understanding on the role that personality plays in social skills by revealing how different neural dynamics underlying social interaction perception are associated with individual differences in agreeableness trait. By integrating findings from both behavioral and neural perspectives, we provide evidence that agreeableness influences multiple stages of social interaction processing, from early, automatic attentional allocation to later, more integrative cognitive process. While acknowledging the limitations related to the lack of direct testing for sex differences, and the preliminary nature of our model, we believe that our findings offer a valuable contribution to the literature on personality and social cognition. Since there has been limited investigation into this research topic thus far, future research should aim at better understanding the role of sex and personality in social processing in both healthy and clinical populations and its effects on behavior. Overall, these findings provide valuable contributions to our understanding of individual differences in the social domain, with potential implications for various fields, including clinical interventions targeting social impairments and fostering tailored interventions that consider individual variations.

Data availability

Raw EEG data, and behavioral data are available at https://osf.io/d2m4c/?view_only=068b6bbc14f84283bda4a9e5d497e21b

References

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. Four ways five factors are basic. Pers. Individ. Dif.13, 653–665 (1992).

DeYoung, C. G. & Allen, T. A. Personality neuroscience and the Five Factor model. In Oxford handbook of the Five Factor Model (ed. Widiger, T. A.) 319–349 (University Press, 2017).

DeYoung, C. G. Personality neuroscience and the biology of traits. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass4, 1165–1180 (2010).

Allen, T. A., Rueter, A. R., Abram, S. V., Brown, J. S. & Deyoung, C. G. Personality and neural correlates of mentalizing ability. Eur. J. Pers.31, 599–613 (2017).

Udochi, A. L. et al. Activation of the default network during a theory of mind task predicts individual differences in agreeableness and social cognitive ability. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci22, 383–402 (2022).

Arbula, S., Pisanu, E. & Rumiati, R. I. Representation of social content in dorsomedial prefrontal cortex underlies individual differences in agreeableness trait. NeuroImage235, 118049 (2021).

Castelli, F., Happé, F., Frith, U. & Frith, C. Movement and mind: A functional imaging study of perception and interpretation of complex intentional movement patterns. NeuroImage12, 314–325 (2000).

Sabbagh, M. A. & Bowman, L. C. Theory of mind. In Stevens’ Handbook of Experimental Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience (eds Ghetti, S. & Wixted, J.) 1–34 (Wiley, 2018).

Saxe, R. & Baron-Cohen, S. The neuroscience of theory of mind. Soc. Neurosci.1, 1–9 (2006).

Schurz, M., Radua, J., Aichhorn, M., Richlan, F. & Perner, J. Fractionating theory of mind: A meta-analysis of functional brain imaging studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.42, 9–34 (2014).

Schurz, M. et al. Toward a hierarchical model of social cognition: A neuroimaging meta-analysis and integrative review of empathy and theory of mind. Psychol. Bull.147, 293–327 (2021).

Tamir, D. I., Thornton, M. A., Contreras, J. M. & Mitchell, J. P. Neural evidence that three dimensions organize mental state representation: Rationality, social impact, and valence. PNAS113, 194–199 (2016).

Pisanu, E., Arbula, S. & Rumiati, R. I. Agreeableness modulates mental state decoding: Electrophysiological evidence. Hum. Brain Mapp.45, e26593 (2024).

Ludwig-Walz, H., Dannheim, I., Pfadenhauer, L. M., Fegert, J. M. & Bujard, M. Anxiety increased among children and adolescents during pandemic-related school closures in Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health17, 74 (2023).

Pisanu, E., Di Benedetto, A., Infurna, M. R. & Rumiati, R. I. Psychological impact in healthcare workers during emergencies: The Italian experience with COVID-19 first wave. Front. Psychiatry13, 818674 (2022).

Isik, L., Mynick, A., Pantazis, D. & Kanwisher, N. The speed of human social interaction perception. NeuroImage215, 116844 (2020).

Guellaï, B., Hausberger, M., Chopin, A. & Streri, A. Premises of social cognition: Newborns are sensitive to a direct versus a faraway gaze. Sci. Rep.10, 9796 (2020).

Mundy, P. A review of joint attention and social-cognitive brain systems in typical development and autism spectrum disorder. Eur. J. Neurosci.47, 497–514 (2018).

Su, J., van Boxtel, J. J. A. & Lu, H. Social interactions receive priority to conscious perception. PLoS One11, e0160468 (2016).

Vestner, T., Tipper, S., Hartley, T., Over, H. & Rueschemeyer, S. A. Bound together: Social binding leads to faster processing, spatial distortion and enhanced memory of interacting partners. J. Vis.18, 448 (2018).

Evans, J. S. Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol.59, 255–278 (2008).

Lieberman, M. D. Social cognitive neuroscience: A review of core processes. Annu. Rev. Psychol.58, 259–289 (2007).

Baron-Cohen, S. Autism: The empathizing-systemizing (E-S) theory. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.1156, 68–80 (2009).

Farris, C., Treat, T. A., Viken, R. J. & McFall, R. M. Perceptual mechanisms that characterize gender differences in decoding women’s sexual intent. Psychol. Sci.19, 348–354 (2008).

Montagne, B., Kessels, R. P. C., Frigerio, E., De Haan, E. H. F. & Perrett, D. I. Sex differences in the perception of affective facial expressions: Do men really lack emotional sensitivity?. Cogn. Process.6, 135–141 (2005).

Alaerts, K., Nackaerts, E., Meyns, P., Swinnen, S. P. & Wenderoth, N. Action and emotion recognition from point light displays: An investigation of gender differences. PLoS One6, e20989 (2011).

Isernia, S., Sokolov, A. N., Fallgatter, A. J. & Pavlova, M. A. Untangling the ties between social cognition and body motion: Gender impact. Front. Psychol.11, 128 (2020).

Pavlova, M., Guerreschi, M., Lutzenberger, W., Sokolov, A. N. & Krägeloh-Mann, I. Cortical response to social interaction is affected by gender. NeuroImage50, 1327–1332 (2010).

Gur, R. C., Gunning-Dixon, F., Bilker, W. B. & Gur, R. E. Sex differences in temporo-limbic and frontal brain volumes of healthy adults. Cereb. Cortex12, 998–1003 (2002).

Paletta, P., Bass, N., Aspesi, D. & Choleris, E. Sex differences in social cognition. In Sex Differences in Brain Function and Dysfunction (eds Gibson, C. & Galea, L. A. M.) 207–234 (Springer International Publishing, 2022).

Proverbio, A. M. Sex differences in the social brain and in social cognition. J. Neurosci. Res.101, 730–738 (2021).

Pernet, C. R., Wilcox, R. & Rousselet, G. A. Robust correlation analyses: False positive and power validation using a new open source matlab toolbox. Front. Psychol.3, 606 (2013).

de Haas, B. How to enhance the power to detect brain–behavior correlations with limited resources. Front. Hum. Neurosci.12, 421 (2018).

Ubbiali, A., Chiorri, C., Hampton, P. & Donati, D. Italian big five inventory. Psychometric properties of the Italian adaptation of the big five inventory (BFI). Appl. Psychol. Bull.59, 37–48 (2013).

Macmillan, N. A. & Creelman, D. C. Response bias: Characteristics of detection theory, threshold theory, and “nonparametric” indexes. Psychol. Bull.107, 401–413 (1990).

Stanislaw, H. & Todorov, N. Calculation of signal detection theory measures. Beh. Res. Meth. Instr. Comp.3, 37–149 (1999).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020).

Klem, G. H., Lüders, H., Jasper, H. H. & Elger, C. E. The ten-twenty electrode system of the international federation. The international federation of clinical neurophysiology. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. Supp.52, 3–6 (1999).

Delorme, A. & Makeig, S. EEGLAB: An open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods134, 9–21 (2004).

Makeig, S., Jung, T.-P., Bell, A. J. & Sejnowski, T. J. Independent component analysis of electroencephalographic data. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 8 (eds Touretzky, D. et al.) 145–151 (MIT Press, 1996).

Pion-Tonachini, L., Kreutz-Delgado, K. & Makeig, S. ICLabel: An automated electroencephalographic independent component classifier, dataset, and website. NeuroImage198, 181–197 (2019).

Perrin, F., Pernier, J., Bertrand, O. & Echallier, J. F. Spherical splines for scalp potential and current density mapping. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol.72, 184–187 (1989).

Delorme, A., Sejnowski, T. & Makeig, S. Enhanced detection of artifacts in EEG data using higher-order statistics and independent component analysis. NeuroImage34, 1443–1449 (2007).

Pernet, C. R., Chauveau, N., Gaspar, C. & Rousselet, G. A. LIMO EEG: A toolbox for hierarchical linear modeling of electroencephalographic data. Comput. Intell. Neurosci2011, 831409 (2011).

Maris, E. & Oostenveld, R. Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG- and MEG-data. J. Neurosci. Methods164, 177–190 (2007).

Pernet, C. R., Latinus, M., Nichols, T. E. & Rousselet, G. A. Cluster-based computational methods for mass univariate analyses of event-related brain potentials/fields: A simulation study. J. Neurosci. Methods250, 85–93 (2015).

Tadel, F., Baillet, S., Mosher, J. C., Pantazis, D. & Leahy, R. M. Brainstorm: A user-friendly application for MEG/EEG analysis. Comput. Intell. Neurosci.2011, 879716 (2011).

Dale, A. M. et al. Dynamic statistical parametric mapping: Combining fMRI and MEG for high-resolution imaging of cortical activity. Neuron26, 55–67 (2000).

Hansen, P. C., Kringelbach, M. L. & Salmelin, R. MEG-An Introduction to Methods (University Press, 2010).

Gramfort, A., Papadopoulo, T., Olivi, E. & Clerc, M. OpenMEEG: Opensource software for quasistatic bioelectromagnetics. BioMed. Eng. Online9, 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-925X-9-45 (2010).

Stenroos, M., Hunold, A. & Haueisen, J. Comparison of three-shell and simplified volume conductor models in magnetoencephalography. NeuroImage94, 337–348 (2014).

Wilcox, R. R., Rousselet, G. A. & Pernet, C. R. Improved methods for making inferences about multiple skipped correlations. J. Stat. Comput. Simul.88, 3116–3131 (2018).

Kosonogov, V. et al. Effects of social and affective content on exogenous attention as revealed by event-related potentials. Cogn. Emot.33, 683–695 (2019).

Schacht, A. & Vrtička, P. Spatiotemporal pattern of appraising social and emotional relevance: Evidence from event-related brain potentials. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci.18, 1172–1187 (2018).

Benning, S. D. et al. Late positive potential ERP responses to social and nonsocial stimuli in youth with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord.46, 3068–3077 (2016).

Cox, A. et al. Diminished social reward anticipation in the broad autism phenotype as revealed by event-related brain potentials. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci.10, 1357–1364 (2015).

Chevallier, C., Kohls, G., Troiani, V., Brodkin, E. S. & Schultz, R. T. The social motivation theory of autism. Trends Cogn. Sci.16, 231–239 (2012).

Dawson, G., Webb, S. J. & McPartland, J. Understanding the nature of face processing impairment in autism: Insights from behavioral and electrophysiological studies. Dev. Neuropsychol.27, 403–424 (2005).

Kikuchi, Y., Senju, A., Tojo, Y., Osanai, H. & Hasegawa, T. Faces do not capture special attention in children with autism spectrum disorder: A change blindness study. Child Dev.80, 1421–1433 (2009).

Fletcher-Watson, S., Findlay, J., Leekam, S. & Benson, V. Rapid detection of person information in a naturalistic scene. Perception37, 571–583 (2008).

Gliga, T., Elsabbagh, M., Andravizou, A. & Johnson, M. Faces attract infants’ attention in complex displays. Infancy14, 550–562 (2009).

Adolphs, R. Cognitive neuroscience of human social behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.3, 165–178 (2003).

Chevallier, C., Huguet, P., Happé, F., George, N. & Conty, L. Salient social cues are prioritized in autism spectrum disorders despite overall decrease in social attention. J. Autism Dev. Disord.43, 1642–1651 (2013).

Agam, Y. & Sekuler, R. Interactions between working memory and visual perception: An ERP/EEG study. NeuroImage36, 933–942 (2007).

Bayer, M. et al. Independent effects of motivation and spatial attention in the human visual cortex. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci.12, 146–156 (2017).

Fellrath, J., Manuel, A. L. & Ptak, R. Task relevance effects in electrophysiological brain activity: Early, but not first. NeuroImage101, 68–75 (2014).

Ibanez, A. et al. What event-related potentials (ERPs) bring to social neuroscience?. Soc. Neurosci.7, 632–649 (2012).

Pavlova, M. K. A dual process model of spontaneous conscious thought. Conscious. Cogn.118, 103631 (2024).

Codispoti, M., Ferrari, V. & Bradley, M. M. Repetition and event-related potentials: Distinguishing early and late processes in affective picture perception. J. Cogn. Neurosci.19, 577–586 (2007).

Schupp, H. T. et al. Affective picture processing: The late positive potential is modulated by motivational relevance. Psychophysiology37, 257–261 (2000).

Baron-Cohen, S., Knickmeyer, R. C. & Belmonte, M. K. Sex differences in the brain: Implications for explaining autism. Science310, 819–823 (2005).

Corbetta, M. & Shulman, G. L. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci3, 201–215 (2002).

Wilkowski, B. M., Robinson, M. D. & Meier, B. P. Agreeableness and the prolonged spatial processing of antisocial and prosocial information. J. Res. Pers.40, 1152–1168 (2006).

Schiller, B., Sperl, M. F. J., Kleinert, T., Nash, K. & Gianotti, L. R. R. EEG microstates in social and affective neuroscience. Brain Topogr.37, 479–495 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to Prof. Leyla Isik for providing the stimuli used in the experimental task.

Funding

This work was funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, Programmazione Triennale PRO3 2021-2023 funds, to RIR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.P.: Conceptualization, methodology, software, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization. S.A.: Conceptualization, methodology, software, data curation, formal analysis, writing—review & editing, visualization. R.I.R.: Conceptualization, writing—review & editing, supervision, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pisanu, E., Arbula, S. & Rumiati, R.I. The role of personality in social interaction perception: an ERP and source imaging study. Sci Rep 14, 22164 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73694-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73694-0