Abstract

The BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant (PV) increases the risk of breast and ovarian cancer; thus, risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) and mastectomy (RRM) are recommended. We evaluated the effects of the graphical display of cancer risk compared with those of numerical presentation on the decision-making for risk-reducing (RR) surgery. A total of 471 women representing the Korean population were recruited. The lifetime risk of breast/ovarian cancer were given numerically followed by graphically in hypothetical BRCA1/2 PV-positive cases. Subsequently, the study participants were asked for their willingness to undergo RRSO/RRM. When the ovarian cancer risk was shown as 44.0%, the percentage of study participants who chose RRSO was 41.0% after numerical presentation versus 39.9% after graphical display, of which the difference was not significant. When the breast cancer risk was presented as 72.0%, 30.4% of the participants opted for RRM under numerical presentation, whereas this increased to 38.6% under graphical display, of which the difference was significant (p < 0.0075). The average levels of the cancer risk which study participants consider RR surgery were 57.1% for ovarian cancer and 60.6% for breast cancer. This suggests that the impacts of different formats of risk communication on decision about RRSO or RRM may be different by the absolute levels of ovarian or breast cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The propensity to develop ovarian and breast cancer in American women is 1.5% and 13.0%, respectively1,2; whereas in South Korea, it is 0.97% and 6.4%, respectively3. Caucasian women who inherit the breast cancer gene 1/2 (BRCA1/2) pathogenic variant (PV) have 39.0–44.0% and 55.0–72.0% higher risk of developing ovarian and breast cancer, respectively, than women without the variant1,4. In South Korea, the lifetime risks of ovarian cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers are 36.9% and 14.9%, respectively, and those of breast cancer are 49.0–59.0% and 35.0–58.0% in BRCA1 and BRCA2 PV carriers, respectively3,5.

Screening at earlier ages, risk-reducing (RR) surgery, and chemoprevention can reduce the risk of cancer in BRCA1/2 carriers1,6. Bilateral oophorectomy or salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) and RR mastectomy (RRM) reduced ovarian and breast cancer incidence by 81–100%6,7,8 and 90–100%, respectively6,9,10,11,12. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines in Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic, Version 2.2024, suggests that women between 35 and 40 years age group who are BRCA PV-positive should be recommended RRSO and RRM after childbearing13. The US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation states that for women with a harmful mutation in the BRCA1/2 genes, the evidence level for RRSO and RRM is moderate6.

Studies conducted from 1994 to 1998 in the USA and the UK showed that 51–64% of unaffected or affected women with BRCA PV underwent RRSO or RRM14,15,16. A recent study performed in 2017 showed an elevated acceptance rate (73.3%) of RR surgery in BRCA PV-positive women17. However, in South Korea, the rate of RR surgery in BRCA carriers was 31.6% before 2013 and 42.5% after 201318. Thus, women with BRCA PV-positive need sufficient assistance for prudent decision-making.

A large body of evidence indicates that patient decision aids are an effective way to enhance informed medical decision making19. The choice of RR surgery depends on the chances of reducing the risk of cancer and associated side effects and complications. The probability of developing cancer in BRCA PV carriers greatly influences the intention to undergo surgery. Thus, the most effective strategy to deliver quantitative information should be sought to help people with high risk of familial cancer make better medical decisions. Graphical formats of delivering quantitative information are presumably more effective, as they hold eye-gaze longer and are more memorable than numerically delivered information20. Icons express probability accurately and enhance the comprehension of ratio and risk estimates21.

In 2016, we conducted a survey to investigate the attitude toward BRCA testing, awareness of cancers associated with BRCA, and the intention to undergo RR surgery18,22,23. We suggested that effective educational materials and counseling strategies facilitate informed decision making22. Although we have updated the earlier study in 2022 by repeating some of the questions, we designed a sub-study to evaluate the effect of a graphical display on decision-making regarding RRSO and RRM in BRCA PV carriers. This study compared the effect of presenting graphical displays, particularly icon arrays, with that of simply providing the numerical value of the ovarian and breast cancer risks on the intention to undergo RRSO and RRM in a hypothetical scenario.

Results

General characteristics of the study participants

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants are shown in Table 1. As in Table 1, 94.1% of the participants were aware of genetic testing. Under the hypothetical assumption of breast cancer diagnosis, 80.7% were willing to undergo a BRCA test. Additionally, 90.1% were willing to inform their family members of the BRCA test results, and 87.8% were willing to recommend the BRCA test to their family members.

Willingness to undergo RRSO or RRM when the cancer risk was presented numerically versus graphically

A total of 41.0% of the participants opted for RRSO when the lifetime ovarian cancer risk was presented numerically (as 44.0%) and 39.9% of the participants chose RRSO when the risk was presented graphically, of which the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.74) (Fig. 1A). When the breast cancer risk was presented numerically (as 72.0%), 30.4% of participants opted for RRM, while 38.6% opted for RRM when the risk was presented graphically, and the difference between the two percentages was significant (p < 0.0075).

Factors associated with willingness to undergo RRM or RRSO when the cancer risk was presented numerically

As presented in Table 2, age groups, education levels, and household income were not associated with willingness to undergo RRM or RRSO in both crude and adjusted models. In the adjusted models, compared with being single, being married was associated with a preference to choose RRSO (odds ratio (OR), 2.34; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.28‒3.97), and being divorced or widowed was associated with a greater tendency to accept RRSO (OR, 3.24; 95% CI 1.19‒8.87) and RRM (OR, 4.41; 95% CI 1.54‒12.72). Having experiences of childbirth was positively associated with the intention to accept RRSO (OR, 1.94; 95% CI 1.15‒3.32). The associations between having further child plans and the intention to undergo RRSO or RRM were not significant. Planning to undergo BRCA test was associated with higher acceptance rates of RRSO (OR, 2.01; 95% CI 1.25‒3.59) and RRM (OR, 4.27; 95% CI 2.16‒9.46) in adjusted models. Similarly, the intention to inform their family members about their BRCA test results and recommend the test to their family members were positively associated with the intention to undergo RRSO (OR, 2.94; 95% CI 1.36‒7.05) (OR, 2.87; 95% CI 1.46‒6.10) or RRM (OR, 5.62; 95% CI 1.96‒23.72) (OR, 3.13; 95% CI 1.44‒7.84). The associations between subjective health conditions and awareness of genetic tests, and acceptance of RRSO or RRM were not significant.

Level of cancer risk at which participants considered undergoing RRSO or RRM

Notably, 75.3% and 74.6% considered RRSO or RRM, respectively, if the ovarian or breast cancer risk was greater than at least 50–59% (Fig. 1B). The average levels of risks of ovarian and breast cancer at which the participants considered undergoing RRSO and RRM were 57.1% and 60.6%, respectively.

Factors associated with a change in decision to undergo RRSO or RRM when the cancer risk was presented as a number in percentage versus pictogram

Fifty participants changed their intention from “will not have RRSO” under a numerical form of risk presentation to “will have RRSO” after viewing graphical representation of the ovarian cancer risk. The associations between age groups, education levels, monthly household income, and marital status, and intention to undergo RRSO or RRM were not significant both in crude or adjusted models (Table 3). Having further child plans was associated with less likelihood to change decision to refuse RRM (OR, 0.21; 95% CI 0.06‒0.60). Subjectively being in excellent or very good health was negatively associated with changing the intention not to undergo RRM (OR, 0.37; 95% CI 0.19‒0.69). Having plans to undergo a BRCA test, and intending to inform family members of BRCA test results were positively associated with changing the decision from refusal to acceptance of RRSO (OR, 2.39; 95% CI 1.01‒6.69) (OR, 4.34; 95% CI 1.21‒27.88) and RRM (OR, 4.10; 95% CI 1.81‒11.01) (OR, 5.44; 95% CI 1.57‒34.30).

Reasons of not choosing RRSO or RRM under numerical versus graphical presentation of risks

Among those who changed the decision from “will not undergo RRSO” to “will undergo RRSO” from a numerical to graphical presentation of ovarian cancer risk (n = 50), 42.0% of women chose not to have RRSO because they “did not have cancer yet (it won’t be too late to be treated after diagnosis)”. Twenty-four percent of women refused RRSO because they were “worried about side effects” (Fig. 2). Twelve percent of the women was concerned about the cost. Ten percent of women refused RRSO because they had child plans. Most of this subgroup answered that they changed their decision because “the risk of ovarian cancer is high” (88.0%).

Major reasons for not choosing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) or mastectomy (RRM) when the cancer risk was presented numerically and the major reasons for choosing RRSO or RRM when the cancer risk was presented graphically. *Participants who first answered “no” to RR surgery under numerical representation but changed their decision to “yes” to the RR surgery under graphical representation of cancer risks.

These patterns were similar in the case of RRM; among 75 participants who changed their decision after viewing graphical display of the breast cancer risk, 36.0% of women said they would not accept RRM because they did not have breast cancer yet. Some of this subgroup worried about side effects (17.3%) or breast-shape change (16.0%). Seventeen percent of this subgroup answered that the cost burden was high. This subgroup changed their decision mostly because the breast cancer risks appeared high when the risk was presented graphically (89.3%).

Discussion

We investigated the attitudes and intentions of the general population toward BRCA genetic testing and RR surgery to reduce the risks of ovarian and breast cancer in non-symptomatic BRCA PV carriers in a hypothetical scenario. Most study participants were positive toward accepting the BRCA test, intending to share the results, and recommending the test to their family members. The intention to undergo RRM increased from 30.4% under numerical risk presentation to 38.6% after a graphical display in this study, which iterates the importance of the formats of risk communication. However, decision making of RRSO was not associated with numerical versus graphical presentation of ovarian cancer risk.

The effects of graphical displays may differ according to the absolute risk of cancer. The average level of cancer risks to consider RR surgery was 57.1% in ovarian cancer and 60.6% in breast cancer. The pictogram showing the lifetime risk of breast cancer (77%) led to inclination toward RR surgery compared to numerical format of the risk presentation. The lifetime risk of breast cancer (77.0%) exceeds the average level of breast cancer risk to consider RRM (60.6%). However, the risk of ovarian cancer shown in the pictogram was 44%, which is lower than the average level of ovarian cancer to consider RRSO (57.1%). The psychological mechanisms underlying the different effects of graphical displays according to the perception about the threshold risk need to be studied further. Nevertheless, our study results suggest that the impact of different formats of risk communication may be related to the absolute levels of disease risks, which should be considered for the strategy of genetic counselling.

When the risks of ovarian and breast cancer were given as percentages in numerical format, being married was associated with increased likelihood of choosing RRSO, and being divorced or widowed was positively associated with opting for RRSO or RRM after adjusting for age, education, and income. This implies that women who are single may be more conservative to surgery of reproductive organs. A previous study reported that unmarried BRCA PV carriers had concerns about losing the chance to get married with expectation of having children24. Also, in our study, women who had experiences of childbirth were more likely to undergo RRSO. This is consistent with a previous study where having children was associated with a higher rate of undergoing RRSO in BRCA PV-positive women25. Although we did not observe the direct association between having further child plans and intention to opt for RRSO, women who had experiences of childbirth may be less resistant to medical procedure leading to infertility. Having plans to undergo the BRCA test and intending to inform the BRCA test results and recommend the test to family members showed clustering with the acceptance of RR surgery. This suggests that a positive attitudes toward genetic tests and RR surgery are associated with each other, and this pattern could be utilized to enhance the effectiveness of genetic counseling.

In our study, 41.0% of the study participants opted for RRSO and 30.4% of women opted for RRM in a hypothetical BRCA PV-positive case when the cancer risks were provided in a numerical form. These rates are relatively higher than those in other studies in similar settings. In a study conducted in 2017 in the US, when young women of low income families were asked about a hypothetical scenario of a high risk of ovarian and breast cancer, 11.8% of Hispanics and 10.7% of non-Hispanics intended to undergo RRSO, and 19.6% of Hispanics and 15.1% of non-Hispanics chose RRM26. In a study conducted in 2005–2007 in the Netherlands among non-affected women, 25.7% of participants intended to undergo RRM27. The intention to undergo RR surgery is higher in individuals who are BRCA1/2 PV-positive than in those who are BRCA1/2 PV-negative. Higher rates of intention to undergo RRSO (30.0%) and RRM (33.3%) were observed in carriers of the BRCA1/2 PV in Indonesian women in 2002–201728. In a study performed in Canada in 2017, 73.3% of the patients with hereditary ovarian cancer underwent RR surgery, including RRSO or bilateral salpingectomy with deferred oophorectomy17.

These variations may be influenced by not only medical conditions including BRCA PV status but also ethnic, racial, and/or religious differences. For example, uptake rate of RRSO was substantially higher in white than non-white in BRCA PV carriers in the USA25. Health insurance system may also impact medical decision affecting affordability of RR surgery. Indeed, in Korea, the number of women who underwent RR surgery increased since 2013 when the National Health Insurance Services (NHIS) of Korea began reimbursement for RRSO in BRCA PV carriers18.

We further analyzed the factors associated with the change in decision making after viewing graphical information in the participants who were initially reluctant to choose RR surgery when the cancer risks were presented numerically. Women who had further child plans were more likely to maintain their decision of refusing RRM even after viewing pictogram. Study participants who perceived their subjective health status as excellent or very good were also more likely to keep their decision of not choosing RRM. Participants who had plans to undergo BRCA test and intentions to inform BRCA test results to their family members were more likely to change their minds form “not choosing RRSO/RRM” under numerical presentation of cancer risks to “choosing RRSO/RRM” under graphical presentation of cancer risks. This suggests that the study participants who are more positive about BRCA test overall may be also more flexible to accept RR surgery under visual presentation of the risks. The most common reason for not choosing RRSO/RRM was that “I do not have ovarian/breast cancer yet (it won’t be too late to be treated after I’m diagnosed)”, and the most common reason for choosing RRSO/RRM under pictogram was “the risk of ovarian/breast cancer is high.” These results indicate that this specific group of people perceived the risk of cancer greater under pictogram rather than under a numerical format of risk presentation. However, this appears to be not applicable for those who have further child plans and those who perceive their health status as excellent or very good. The characteristics of study participants may influence the effects of different formats of risk communications, which should be taken into account when developing decision aids. Further studies are required for validating these results, especially in women who are BRCA PV carriers.

Furthermore, the types of graphic display may affect decision making. Several formats have been tested for the effects on medical decision making. In Australian study, risk communication formats such as government recommendation, icon array, expected frequency trees, and line graph were applied to deliver information about risks and benefits of colorectal cancer29 as a part of the development of a colorectal cancer risk prediction (CRISP) tool30. A similar approach was used to communicate the benefits and harms of taking aspirin for colorectal cancer prevention31 and taking selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) to reduce breast cancer risk32. On-line breast cancer risk assessment and management tools have been developed utilizing diverse risk communication formats such as in iPrevent33,34. Thus, in the further study, more diverse forms of risk communication need to be investigated to deliver information about cancer risk in BRCA PV-positive individuals.

Although we have used 100 (10 × 10) icon array (Supplementary Material), as the risks of breast and ovarian cancer are substantially high in BRCA PV-positive individuals, 1000 icon arrays, such as 20 × 5029,30,32 or 25 × 4031,33, are commonly used in other studies, most of which are used for the disease with relatively lower risks. If the risks of breast and ovarian cancer in BRCA PV-positive individuals are presented in 1000 icon arrays, the risks may be perceived in quite a different way. Particularly, if the breast and ovarian cancer risks in general female population are presented in 1000 icon array simultaneously for comparison, it may provide women in high risks of ovarian or breast cancer with an opportunity to interpret their risks more effectively, which would be worthwhile to consider for future studies.

Major goals of improving the quality of medical decision process regarding RRSO and RRM are not mere to raise the uptake rate of RR surgery, but to empower women in high risk of cancer to make important decisions in their lives. This can be achieved partly by enhancing knowledge about preventive measures through providing tools to understand quantitative information about the disease risk more accurately and effectively, which could eventually promote informed choice and reduce decision conflict35,36,37.

This study was not designed as a randomized controlled trial or crossover design; thus, the causal relationship between graphical display and the intention to undergo RRSO or RRM needs cautious interpretation. Moreover, the sequence of presenting numerical and graphical information may influence a study participant’s perception about the risk. Further studies are required to examine the effects of the order of viewing the different presentation formats on medical decision making.

Conclusion

The intention to undergo RRSO did not change according to the different methods of risk presentation; however, the acceptance rate of RRM increased when the pictogram was provided rather than the numerical presentation. This study may suggest a hypothesis for a further study to investigate if the impacts of different formats of risk communication on decision about RRSO or RRM are different by the absolute levels of ovarian or breast cancer.

Methods

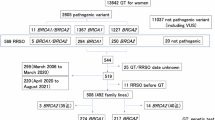

Study participants, design, and setting

A total of 471 study female participants aged 20–74 were recruited between July 20, 2022, and August 31, 2022. We have only included women, as the decisions of accepting RRSO and RRM are primarily dependent on women. Although male family members and friends may influence women’s choice regarding the prophylactic surgery, this influence was not the scope of this study. The study populations were selected by stratified random sampling based on age and residential areas according to the register-based census of South Korea as of June, 2022. The inclusion criteria for research participants were healthy women without cancer, aged 20–74 years, who could fully understand the Korean language, and agreed to participate in the survey. After obtaining informed consent from the study participants, trained research personnel conducted a 1:1 face-to-face interview using a structured questionnaire. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the National Cancer Center Korea (IRB #NCC 2022-0182). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations including Declaration of Helsinki.

Structure and flow of the questionnaire

The survey questionnaire consisted of six questions about BRCA genetic testing, 12 questions about the perceptions of RRSO and RRM according to the presentation of ovarian and breast cancer risks by numerical versus graphical methods, and other questions to obtain demographic information. Questions about perception and attitudes toward genetic tests included determining if participants were aware of genetic testing, if they would share the BRCA test results with their family members, and if they would recommend BRCA test to their family members. The participants were asked if they would undergo RRSO or RRM if they were BRCA PV-positive after providing them with the lifetime risks of ovarian and breast cancer numerically and graphically, which are shown in the questionnaire (Supplementary Material).

The flow of the key questions is provided in Fig. S1. Participants were given a hypothetical scenario of being diagnosed as BRCA PV-positive but without a symptom or diagnosis of ovarian or breast cancer. The epidemiology and characteristics of ovarian/breast cancer were introduced, including the incidence rate at the population level and the lifetime cumulative risk if BRCA PV-positive, which was numerically presented in percentage. For the simplicity and efficiency of the questionnaire, we provided the risk of ovarian/breast cancer based only on the BRCA1 PV instead of using two different risks for BRCA1 and BRCA24. After the benefits, complications, side effects, and cost of RRSO/RRM were explained, participants were enquired about their intention to undergo RRSO/RRM and the reason behind it. Then, the participants were asked at what probability of ovarian/breast cancer risk they would consider undergoing RRSO/RRM. Afterwards, the ovarian/breast cancer risk was presented as a pictogram, and the intention to accept RRSO/RRM was assessed. A graphical presentation of the risk of cancer was provided as an 10 × 10 icon array (Fig. S1, Supplementary Material), with background and foreground estimates as suggested by Trevena et al.19 and Tubau et al.21.

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the study participants were analyzed using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and a chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables to compare groups. The t-test was used to test the significance of the difference in the tendency to choose RRSO or RRM when the ovarian or breast cancer risk was presented via numerical or graphical methods. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to identify the factors contributing to the intention to choose RRSO or RRM after the graphical display of ovarian or breast cancer risk. As shown in Table 1, the factors included age, educational levels, monthly household income, marital status, experience of childbirth, having further child plans, and subjective health condition. We have used the five-category perception of general health (excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor) which showed linear and non-linear correlation with SF-36 profile in a previous study38. We also investigated the association between the intention to undergo RRSO/RRM and the following: awareness of BRCA test, plan to undergo BRCA test, intention to inform BRCA test results to family members, and intention to recommend BRCA test to family members. The multivariate logistic regression model was adjusted for age group, educational level, and monthly household income levels, with categories shown in Table 1. Similarly, factors associated with changes in decision from “will not choose RRSO/RRM” to “will choose RRSO/RRM” were estimated using univariate and multivariate logistic regression models described earlier. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used R version 4.3.0 (R Development Core Team, https://cran.r-project.org/) for the statistical analyses.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the National Cancer Center Korea (IRB #NCC 2022-0182). Informed consent was obtained from all the study participants.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available as their containing information could compromise the privacy of research participants, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

BRCA Gene Mutations: Cancer risk and genetic testing. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/genetics/brca-fact-sheet.

Howlader N, N. A. et al. SEER cancer statistics review. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2017/ (1975–2017).

Park, K. S. et al. A population-based analysis of BRCA1/2 genes and associated breast and ovarian cancer risk in Korean patients: A multicenter cohort study. Cancers (Basel) 13, 2192. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13092192 (2021).

Kuchenbaecker, K. B. et al. Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. JAMA 317, 2402–2416. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7112 (2017).

Park, B. et al. Attitudes toward risk-reducing mastectomy and risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy among young, unmarried, healthy women in Korea. Cancer Res. Treat. 54, 375–382 (2021).

Owens, D. K. et al. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 322, 652–665. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.10987 (2019).

Rebbeck, T. R. et al. Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 1616–1622. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa012158 (2002).

Finch, A. P. et al. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 1547–1553. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.53.2820 (2014).

Hartmann, L. C. et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a family history of breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 340, 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199901143400201 (1999).

Hartmann, L. C. et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation carriers. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 93, 1633–1637. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/93.21.1633 (2001).

Evans, D. G. R. et al. Risk reducing mastectomy: outcomes in 10 European centres. J. Med. Genet. 46, 254–258. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmg.2008.062232 (2009).

Skytte, A. B. et al. Breast cancer after bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy. Clin. Genet. 79, 431–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01604.x (2011).

Daly, M. B. et al. NCCN Guideline Version 2.2024. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: Breast, ovarian, and pancreatic. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_bop.pdf (2023).

Kauff, N. D. et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in Women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 1609–1615. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa020119 (2002).

Lodder, L. N. et al. One year follow-up of women opting for presymptomatic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2: emotional impact of the test outcome and decisions on risk management (surveillance or prophylactic surgery). Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 73, 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015269620265 (2002).

Meijers-Heijboer, E. J. et al. Presymptomatic DNA testing and prophylactic surgery in families with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Lancet 355, 2015–2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02347-3 (2000).

Jacobson, M. R. et al. Factors affecting surgical decision-making in carriers of BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants undergoing risk-reducing surgery at a dedicated hereditary ovarian cancer clinic. Menopause 29, 151–155. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001900 (2021).

Lee, E. G. et al. Different patterns of risk reducing decisions in affected or unaffected BRCA pathogenic variant carriers. Cancer Res. Treat. 51, 280–288. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2018.079 (2019).

Trevena, L. J. et al. Current challenges when using numbers in patient decision aids: Advanced concepts. Med. Decis. Mak. 41, 834–847. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X21996342 (2021).

Smerecnik, C. M. R. et al. Understanding the positive effects of graphical risk information on comprehension: Measuring attention directed to written, tabular, and graphical risk information. Risk Anal. 30, 1387–1398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01435.x (2010).

Tubau, E., Rodríguez-Ferreiro, J., Barberia, I. & Colomé, À. From reading numbers to seeing ratios: a benefit of icons for risk comprehension. Psychol. Res. 83, 1808–1816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-018-1041-4 (2019).

Chang, Y. J. et al. Differences in willingness to undergo BRCA1/2 testing and risk reducing surgery among the general public, cancer patients, and healthcare professionals: A large population-based survey. J. Pers. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12050818 (2022).

Eum, H. et al. Differences in attitudes toward genetic testing among the public, patients, and health-care professionals in Korea. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 26, 1432–1440. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-018-0191-6 (2018).

Sa’at, H. et al. Decision-making for risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) in Southeast Asian BRCA mutation carriers with breast cancer: A qualitative study. Int. J. Behav. Med. 29, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-021-09984-y (2022).

Bradbury, A. R. et al. Uptake and timing of bilateral prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Genet. Med. 10, 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e318163487d (2008).

Guo, F. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, willingness to pay, and patient preferences about genetic testing and subsequent risk management for cancer prevention. J. Cancer Educ. 37, 362–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01823-0 (2022).

van Driel, C. M. G. et al. Psychological factors associated with the intention to choose for risk-reducing mastectomy in family cancer clinic attendees. Breast 30, 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2016.08.016 (2016).

Padmanabhan, H. et al. Psychosocial outcome and health behaviour intent of breast cancer patients with BRCA1/2 and PALB2 pathogenic variants unselected by a priori risk. PLoS One 17, e0263675. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263675 (2022).

Kim, G. et al. The CRISP-Q study: Communicating the risks and benefits of colorectal cancer screening. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 47, 139–145 (2018).

Walker, J. G. et al. The CRISP colorectal cancer risk prediction tool: an exploratory study using simulated consultations in Australian primary care. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 17, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-017-0407-7 (2017).

Nguyen, P. et al. Benefits and harms of aspirin to reduce colorectal cancer risk: a cross-sectional study of methods to communicate risk in primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 69, e843–e849. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp19X706613 (2019).

McIntosh, J. G. et al. Benefits and harms of selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) to reduce breast cancer risk: a cross-sectional study of methods to communicate risk in primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 69, e836–e842. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp19X706841 (2019).

Keogh, L. A. et al. Consumer and clinician perspectives on personalising breast cancer prevention information. Breast 43, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2018.11.002 (2019).

Lo, L. L. et al. The iPrevent online breast cancer risk assessment and risk management tool: Usability and acceptability testing. JMIR Form. Res. 2, e24. https://doi.org/10.2196/formative.9935 (2018).

McAlpine, K., Lewis, K. B., Trevena, L. J. & Stacey, D. What is the effectiveness of patient decision aids for cancer-related decisions? A systematic review subanalysis. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1200/cci.17.00148 (2018).

Si, J. et al. Decision aids on breast conserving surgery for early stage breast cancer patients: a systematic review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 20, 275. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-020-01295-8 (2020).

Yu, L. et al. Web-based decision aids to support breast cancer screening decisions: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 9, 985–1002. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer-2020-0052 (2020).

Shmueli, A. Subjective health status and health values in the general population. Med. Decis. Mak. 19, 122–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989x9901900202 (1999).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the survey personnel and study participants of this study. This study was supported by the National Cancer Center, South Korea (grant no. 2110181, 2210870).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y-JC, HC, BP, S-YJ, KHR, MCL, YJC, and S-YK conceived and designed the study. Y-JC, YP, YJC, and SYK collected the data. Y-JC and YP performed the data analysis and prepared the manuscript. HC, BP, S-YJ, KHR, MCL, and SJP contributed to discussion. SJP prepared graphical works. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, YJ., Park, Y., Park, B. et al. Impact of graphical display on the intention to undergo risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and mastectomy in individuals positive for BRCA pathogenic variant. Sci Rep 14, 24281 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73929-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73929-0