Abstract

Spin-wave devices have recently become a strong competitor in computing and information processing owing to their excellent energy efficiency. Researchers have explored magnons, the quanta of spin-waves, as an information carrier and significant progress has occurred in both excitation and computation. However, most transmission designs remain immature in terms of data rate and information complexity as they only utilize simple spin-wave pulses and suffer from signal distortion. In this work, using micromagnetic simulations, we demonstrate a spin-wave transmitter that operates reliably at a data rate of 4 Gbps over significant (multi-micron) distances with error rates as low as 10−14. Spin-wave amplitude is used to encode information. Carrier frequency and data rate are carefully chosen to restrict dispersion spreading, which is the main reason for signal distortion. We show that this device can be integrated into either pure-magnonic circuits or modern electronic networks. Our study reveals the potential for achieving an even higher data rate of 10 Gbps and also offers a comprehensive and logical methodology for performance tuning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spin-wave devices, or magnonics, have drawn much attention in the past decade due to their promising applications in computing and information processing1,2,3,4,5. Utilizing the collective behavior of the electron spins, magnonics show significant advantages in terms of energy efficiency over their electronic counterparts, which inherently suffer from Joule heating caused by electron movement. In addition, spin-waves could benefit from their GHz to THz frequency6,7, submicron to nanometer scale wavelength and nonlinear behaviors, which are all essential for building compact chips for logic computation and communication.

Tremendous efforts have been made to exploit spin-wave-based information transmission, but there is a need to overcome major challenges such as the excitation and transport of spin-waves. High frequency, short wavelength, exchange-dominated propagating spin-waves are especially indispensable for this application; thus, excitation schemes must offer high frequency and compactness. Spin torque nano-oscillators (STNO) utilizing spin-transfer torque are a popular and reliable option owing to their excellent wavelength tunability and ease of operation8,9,10. Spin-Hall nano-oscillators (SHNO), which are more easily fabricated because they have less layers than STNOs, are used as well11,12,13,14. Spin-waves can be induced by the auto-oscillation from the STNO or SHNO free layer through either exchange11,15 or dipolar coupling16. A spin-wave frequency up to 46 GHz17 and a wavelength down to 74 nm8 have been reported. Alternative methods have also been proposed, such as the use of domain walls18, ultrashort light pulses6,7, voltage-controlled magnetic anisotropy effect19, etc.

As excitation techniques have improved over time, various spin-wave transmission plans have also been designed. J. Chen et al. reported a reconfigurable spin-wave interferometer for wave-based computing applications20. Spin-wave logic circuits have been constructed as demonstrated by the emergence of spin-wave majority gates21 and the magnonic directional coupler5,22, where information is encoded into the phase and amplitude of the spin-waves. A. Mahmoud et al. introduced a fanout cascading mechanism in order to build larger spin-wave logic circuit networks3. Moreover, manipulation of spin-wave propagation direction through magnetization gradients has been realized23 and spin-wave amplifiers have been proposed to compensate for damping loss24.

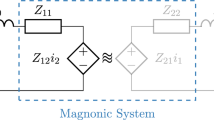

In order to make these spin-wave devices a useful substitute for modern CMOS chip components, high data rates are crucial. Unfortunately, the above-mentioned designs all suffer from a poor data rate that can hardly compete with leading edge 3–4 GHz CPU clock rates, which usually translates into data rates higher than 4 Gbps. For example in Ref.21, a clock rate of only 88.5 MHz is achieved and in Ref.22, the data rate is estimated to be less than 100 Mbps. In fact, in these designs, only very simple information such as single-tone bit sequences are transmitted and the interval between these bits has to be long enough so that the detection would not be ruined by the signal distortion. In other words, a transmission scheme that could satisfy both high data rate and good information complexity has not yet been developed. Also, in many of these previous studies, spin-wave detection is done by converting these magnetic signals back to electric signals through micro-antennas or STNOs, it is likely better, however, to assemble a purely magnonic system22 because the conversion between electric and magnetic signals consumes much energy.

Here in this article, with the help of micromagnetic simulations, we first demonstrate a spin-wave transmitter design that could send pseudorandom binary sequences (PRBS) reliably at a data rate of 4 Gbps while maintaining excellent signal quality. An amplitude shift keying (ASK) modulation technique is used, where the information is encoded into the amplitude of the spin-waves. Phase and frequency shift keying (PSK and FSK) methods are also explored. The cause of signal distortion is comprehensively discussed. Furthermore, we show that this device can be either directly connected to all-magnonic circuits with no add-ons or integrated into modern electronic networks with appropriate converters. For the latter case, we design a demodulation and detection circuit and characterize the device performance using metrics like signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and bit error rate (BER). Our device is capable of sending spin-waves over a distance of \(\:6.6\:\mu\:m\) while keeping the BER below \(\:{10}^{-6}\). Various sample sizes and carrier frequencies are investigated, which opens the possibility to achieve an even higher data rate of 10 Gbps. A comparison to current CMOS on-chip interconnects is presented. Magnetic properties are tuned by changing the applied magnetic field and the exchange coupling strength in order to further improve performance.

Results

Dispersion relation

In order to determine the optimal way to transmit the spin-waves, multiple system configurations are simulated and their corresponding dispersion relations are studied. Figure 1a schematically depicts the final device design, where a transmitter and a receiver are placed on top of a thin film waveguide. Yttrium iron garnet (YIG), a popular candidate for magnonic devices by virtue of its ultra-low spin-wave damping, is chosen as the waveguide material. This YIG thin film has a length of 41 μm and an equal width and thickness of 50 nm. Successful fabrication of YIG thin film with lateral dimensions down to this level has been reported25. A typical saturation magnetization \(\:{M}_{s}=145\frac{emu}{{cm}^{3}}\) is used. An absorbing boundary condition is applied on one end of the waveguide by linearly increasing the damping constant to make sure that the spin-wave reflection is cancelled. Practically, this can be realized through doping, possibly with rare earth elements. Both transmitter and receiver can be either electronic or magnonic devices depending on different input and output requirements. A home-grown GPU-based micromagnetics solver is used26,27,28,29,30. Details on system parameters and simulation techniques can be found in Methods.

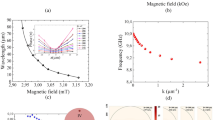

Two different magnetization configurations are investigated first: in-plane longitudinally saturated (along x) and in-plane transversely saturated (along y). The dispersion relations are plotted in Fig. 1b (see Methods for calculation details). Since our purpose is to propagate spin-waves straight along the waveguide length, the only wavevector component of interest here is \(\:{k}_{x}\:\)(with \(\:{k}_{y}={k}_{z}=0\)). The ‘along x’ scenario is in fact an energetically favorable state of this magnetic waveguide due to its relatively large length. Spins spontaneously align themselves across this long axis as a result of the magnetostatic field distribution. While no external bias field is needed in this case, which appears to be a tempting advantage, the problem is that the spin-wave propagation (characterized by y and z components of the magnetization) suffers from strong demagnetization effects at the sample edges. This can be seen from the low \(\:{k}_{x}\) region of the solid blue curve in Fig. 1b. Spin-wave group velocity \(\:{v}_{g}=\frac{d\omega\:}{dk}\) drops to 0 here, indicating a non-propagating feature. The ‘along y’ case, on the other hand, shows a much smaller dipolar-dominated region, as presented by the solid red curve in Fig. 1b. Although an external field of 950 \(\:Oe\) is required to saturate the sample, the majority of excitable low-frequency spin-waves now reside in the exchange-dominated region and are allowed to have reasonable group velocities for propagation. This propagation geometry is similar to that in the Damon-Eschbash spin-wave (DESW) configuration31,32, where spin-wave propagation direction is perpendicular to the applied field, except that now the spin waves are exchange-dominated and are no longer confined to the sample surface. As will be discussed later, spin-wave distortion is closely related to non-linearity of the dispersion curve. Thus, a linear fit is performed on both curves for \(\:5\times\:{10}^{5}{cm}^{-1}\le\:{k}_{x}\le\:1.25\times\:{10}^{6}{cm}^{-1}\). The results are denoted by the dashed lines in Fig. 1b. The coefficient of determination \(\:{R}^{2}\) of the ‘along y’ curve fitting (pink-colored) is closer to 1, suggesting a better linear regression approximation and thus a better linearity. Based on these comparisons, we decide to adopt the in-plane transversely saturated magnetization configuration for a better transmission quality under both low and high spin-wave frequencies. Out-of-plane magnetized configuration (along z) results are not presented here since they are exactly the same as those of the ‘along y’ case owing to symmetry.

Spin-wave transmitter design, dispersion relation and waveguide width test. (a) Schematic of the high data rate spin-wave transmitter. (b) Dispersion relations (solid curves) for two different magnetization configurations (sketched next to the curves). The dashed lines correspond to the linear fitting results of the dispersion relations under high \(\:{k}_{x}\:(5\times\:{10}^{5}\sim1.25\times\:{10}^{6}{cm}^{-1})\). \(\:{R}^{2}\) is the coefficient of determination for the linear regressions. (c) Y component of magnetization \(\:{M}_{y}\) along the waveguide width for three different widths. The width axis is normalized.

The role of the aspect ratio of the sample’s width over thickness is also studied. When the width is extended, the external field that is needed to saturate the sample is reduced whereas the magnetization at the sample edges becomes more tilted, as shown in Fig. 1c. This is also referred to as the dipolar pinning effect33,34, which can be suppressed by making this aspect ratio approach unity. Hence, by using an equal thickness and width geometry here, we can minimize the spin-wave signal distortion caused by magnetization nonuniformity along the sample’s two short axes.

Single frequency spin-wave propagation and decay behavior

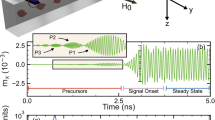

The in-plane transversely magnetized dispersion relation has revealed that any spin-wave with a frequency on this curve should be able to propagate with a non-zero group velocity. It is then of great importance to examine the propagation performance to see if these spin-waves could qualify as an information carrier. Figure 2a shows a snapshot of the spatial magnetization distribution of a spin-wave that has traveled \(\:4\sim8\:\mu\:m\). In this test, a frequency of 18 GHz is first chosen because the dispersion curve at this frequency promises a large spin-wave group velocity and an excellent dispersion linearity. The transmitter keeps exciting spin-waves at this frequency for a total simulation time of 36 ns. Experimentally, this excitation can be realized by using STNO and SHNO devices14,17. The spatial magnetization data \(\:{M}_{x},\:{M}_{y}\) and \(\:{M}_{z}\) of all the cells in the waveguide are recorded every \(\:2.5\:ps\). These data are then averaged over the waveguide width in order to simulate the actual output signals detected by the receiver. Thermal fluctuation fields are not included in this test as we only want to identify the intrinsic spin-wave degradation. The spin-waves presented in Fig. 2a maintain a very good quality over a long distance. No obvious signal distortion is seen and the decay is insignificant, which is characterized by the small difference between the spin-wave amplitudes and its initial value (indicated by the dashed lines). The spin-wave power loss can then be quantified based on this decay behavior. Figure 2b presents the change of main magnetization component \(\:{M}_{y}\) over distance. An exponential fitting is then performed on the data to calculate the spin-wave decay rate. The power loss rate of our device is calculated as \(\:{P}_{loss}^{magnonic}=5.56\times\:{10}^{-11}\:Watts\). Detailed calculations can be found in Methods.

Single frequency spin-wave propagation and power loss. (a) Snapshot of spatial magnetization data \(\:{M}_{x}\) of propagating spin-waves. Dashed lines are the original spin-wave amplitude at the magnon source. (b) Averaged spatial \(\:{M}_{y}\) data (blue circles) and the exponential fitting (red curve). The dashed line denotes the saturation magnetization. Fitting function and coefficients are presented in the box.

Modulation

Having established that the single frequency spin-waves are capable of traveling steadily over a long distance, single-tone binary sequences, or spin-wave pulses, can then be easily transmitted by simply turning on and off the magnon source. However, when it comes to sending realistic information such as a PRBS, which is much more complicated, strict modulation has to be implemented. In analogy to radio-frequency communication techniques, here we utilize these single frequency spin-waves as a carrier signal, and then encode information into the amplitude of these spin-waves, as depicted in Fig. 3a. This is known as the ASK digital signal modulation.

The modulated source signal is shown in Fig. 3b. A carrier frequency \(\:{f}_{carrier}=18\:GHz\) is used again. The input signal is a PRBS of order 5 that contains 31 bits, which are denoted in the blue and yellow bar on top. Bit time is 0.25 ns, which gives a data rate of 4 Gbps. The spin-wave amplitude is defined by the transverse magnetization components with respect to the external field direction: \(\:{M}_{x}\) or \(\:{M}_{z}={M}_{s}\text{sin}\theta\:\), with \(\:\theta\:\) being the precession angle, which switches between \(\:10^\circ\:\) and \(\:0^\circ\:\) at the magnon source according to the input bits.

Figure 3c shows the appearance of the modulated signal when it has traveled \(\:1.5\:\mu\:m\) away from the source. A spin-wave group velocity of \(\:\sim1785\:m/s\) is recorded. An adequate signal quality is preserved as the “1” and “0” bits are clearly distinguishable from each other. No significant decay is observed although a slight signal distortion starts to appear. Small signal tails, or degraded signal squareness, are seen at bit transitions. In fact, the spectrum of a PRBS signal consists of many frequency lobes, each occupying a bandwidth of 4 GHz (always equal to the data rate)35. The integrity of the main lobe along with the first several side lobes are crucial for a good signal squareness (see Supplementary Note 1 for a full description). However, due to the non-linearity of the dispersion relation, spin-waves with different frequencies have different group velocities and thus inevitably end up separated from each other during propagation, resulting in loss of the signal integrity and thus the rounded shape of the wave packets (as shown in Supplementary Fig. S1d). This will eventually impact the signal detection as the bits overlap with each other. Consequently, a larger bit interval has to be used to make space for this signal distortion especially when a longer transmission distance is demanded, which in turn limits the data rate. This also explains the preference of a high \(\:{f}_{carrier}\) in the more linear region of the dispersion curve over those with low frequencies and worse linearities (\(\:<10\:GHz\)).

Spin-wave modulation and demodulation. (a) ASK modulation of the carrier spin-wave signal using a PRBS as input signal. (b) ASK-modulated magnon source signal. The blue and yellow bar on top denotes the input bit states. The dashed lines separate the bits with a bit time of 0.25 ns. (c) Spin-wave signal at \(\:1.5\:\mu\:m\) away from the source. (d) Demodulation results of the received signal in c.

PSK and FSK modulation techniques are also studied (see Supplementary Note 2). Both of them offer a better performance only at small distances and overall are not a better choice than ASK method due to the unacceptable cost of much larger and more sophisticated circuit structures.

Demodulation and signal performance

This high data rate signal can then be used to excite new spin-waves or conduct spin-wave-based logic computations if multiple waveguides are connected properly5,20. As stated earlier, this purely magnonic circuit design is preferred as it avoids the expensive conversion between electric and magnetic signals, but here we also want to explore the possibility to integrate this device into modern electronic chips. Thus, a legitimate demodulation process is needed and the output can then be analyzed by using mature signal processing tools. This also helps better characterize the system. In order to collect and convert the magnetic signals, magneto-resistive effect9 and STNOs16 can be used. For ASK-modulated signals, a standard envelop extraction method is used for demodulation36,37. No extra synchronous signal is needed and thereby this method is simple and inexpensively implemented. Details can be found in Methods. Figure 3d displays the demodulation result of the signal in Fig. 3c, which is received at a distance of \(\:1.5\:\mu\:m\). The information embedded in spin-wave amplitudes is successfully decoded, as can be seen from the distinct “0” and “1” states.

To characterize the transmission performance, the dependence of SNR and BER on propagation length is calculated and plotted in Fig. 4. Calculation details can be found in Methods. A Viterbi detector provides a significant enhancement of BER results over a threshold detector at a cost of much larger and more complicated circuit structures.

Based on different operating scenarios, BER criteria might change. So here we define two propagation lengths accordingly. The first one is for intra-chip application where the BER shall be lower than \(\:{10}^{-6}\). The information transmission for this case happens inside a single chip so that only simple circuits like a threshold detector can be used. An example might be the memory part in a chip where modest error correction occurs. The second one is for arithmetic logic unit (ALU) level applications and a very strict standard of \(\:{10}^{-14}\) is required for BER. For this case, the waveguide might be the basic logic computation unit by itself or connecting these components and no error correction circuit is allowed at this level. Therefore, the BER must be as low as possible and the propagation length is very limited in this case. When it comes to inter-chip applications, where the communication happens in between chips that are distant from each other, it will be affordable to use more powerful but also complex detectors and error correction circuits such as the above-mentioned Viterbi detector and thus a higher BER is tolerable. However, this long-distance scenario turns out to be less important and here we only focus on the two short-distance cases. Figure 4d yields substantial propagation length of \(\:6150\:nm\) and \(\:4020\:nm\) respectively based on the above two standards, indicating the suitability of our device for various applications.

SNR and BER performance for the 4 Gbps transmission scheme. (a) SNR performance over distance under two different temperatures. The error is typically less than 0.3 dB and thus not shown. (b) BER performance over distance under two different temperatures. Threshold detector and Viterbi detector are used to obtain BERs. (c) SNR-BER fitting for the two temperatures. BER data from threshold detector are used. (d) Extrapolation of BER data based on the SNR-BER fitting in (c).

All the discussions above use a room temperature assumption. We also test our device under a reduced temperature (\(\:T=30\:K\)). The results are shown in Fig. 4. It is not surprising to see an improvement for both SNR and BER down at \(\:30\:K\) because spin-waves, or tiny magnetic perturbations, are naturally sensitive to thermal agitations. At \(\:distance=15\:\mu\:m\), as can be found in Fig. 4b, the ratio of the threshold-detected BERs under two temperatures (\(\:\frac{1.792\times\:{10}^{-3}}{5.018\times\:{10}^{-2}}=3.57\%\)) gives a rough estimate on the effect of thermal fluctuations on spin-wave propagations. In fact, at this distance, almost 96.5% of the noises come from the thermal fluctuations. This BER ratio climbs quickly as the propagation distance gets longer, suggesting that at larger distances, thermal fluctuations play a less significant role and more errors are caused by the intrinsic non-linearity of the system. Note that in reality, under ultralow temperatures, spin-wave attenuation could become much stronger because of the coupling of magnons to the impurity ions in the YIG film or to the stray field from the paramagnetic GGG substrate38,39. These effects are not included here as we only care about the effect of thermal field strength.

Width effect and carrier frequency selection

Based on the low temperature results, the signals are primarily prone to thermal-induced errors for short to intermediate distances. Thus, in order to optimize the propagation performance especially for these distances, larger line width is investigated as it could make the system more thermally stable. Here, the aspect ratio of width over thickness is always kept as 1. Propagation lengths under different sample widths are plotted in Fig. 5a. The carrier frequency is kept as \(\:18\:GHz\). The blue and red curves represent the intermediate and short distance propagation performance. In fact, increasing the sample volume is found to suppress the thermal agitation, which can be seen from the rise of the two curves, but it also favors a stronger magnetostatic effect at the sample edges, which ultimately decreases the propagation performance. With a width and thickness of 72 nm, the two propagation lengths can be improved to \(\:6620\:nm\) and \(\:4380\:nm\) respectively.

A thorough study on carrier frequency is also conducted to justify the \(\:{f}_{carrier}\) choice of \(\:18\:GHz\) for the above tests. The dependence of the propagation lengths on carrier frequency is shown in Fig. 5b. For both intra-chip-level (blue curve) and ALU-level (red curve) applications, the transmission behavior peaks around \(\:18\sim20\:GHz.\) Two boundaries appear as the performance worsens under both high and low carrier frequencies. The lower boundary simply comes from the modulation requirements and is designated the modulation boundary. Similar to what happens in wireless communication, here the ratio of the carrier frequency and the input signal frequency, or the data rate, has to be higher than a certain value; otherwise the modulation automatically fails. As for a data rate of 4 Gbps in this case, we empirically suggest a ratio around 5 (\(\:{f}_{carrier}\sim20\:GHz\)) since carrier frequencies that are below \(\:15\:GHz\) present poor results. When the carrier frequency is too high, on the other hand, spin-wave decay increases and limits the performance. The spin-wave decay length \(\:{\lambda\:}_{r}=\frac{{v}_{g}}{2\alpha\:\omega\:}=\frac{d\omega\:}{dk}\frac{1}{2\alpha\:\omega\:}\) is closely related to its frequency10, thus defining the decay boundary as shown in Fig. 5b.

Discussion

Potential for 10 Gbps data rate

Future computers will demand even higher data rates and lower energy cost. The two boundaries in Fig. 5b suggest a technique for obtaining superior performance by further increasing the carrier frequency. Therefore, we make an ambitious extrapolation on data rate, pushing it up to 10 Gbps, and determine a feasible system. Since the data rate has increased, the two boundaries increase accordingly. Based on the 4 Gbps data set and currently available spin-wave excitation schemes, we set the ratio of carrier frequency over data rate to be 4, which gives a carrier frequency of \(\:40\:GHz\). Again, 1116 bits are transmitted using ASK-modulated spin-waves and the results are plotted in Fig. 6. Even though the SNR and BER performance deteriorates at a faster rate than that in Fig. 4, a surprisingly high transmission quality is still obtained. Figure 6d gives a propagation length of \(\:3000\:nm\) and \(\:1520\:nm\) for intra-chip-level and ALU-level applications respectively, which may be sufficient for on-chip computation and communication considering the ultra-high data rate.

SNR and BER performance of the 10 Gbps transmission scheme. (a) SNR performance over distance. The error is typically less than 0.4 dB and thus not shown. (b) BER performance over distance. Threshold detector and Viterbi detector are used to obtain BERs. (c) SNR-BER curve fitting. (d) Extrapolation of BER data based on the SNR-BER fitting in (c).

Performance comparison against modern CMOS on-chip interconnects

In order to examine the energy efficiency of our spin-wave device relative to its electronic counterparts, we conduct a performance comparison against modern CMOS on-chip interconnects. For our spin-wave transmitter, two operating modes are included: 4 Gbps and 10 Gbps. Table 1 compares their energy consumption per bit, bandwidth density and propagation latency. Spin-wave group velocity is also listed. Our spin-wave transmitter exhibits great advantage in energy efficiency over CMOS on-chip interconnect wirings. For each bit transmitted using spin-wave carriers, the dissipated energy is lower by a factor of 17,800 (4 Gbps) and 13,500 (10 Gbps). The energy consumption for CMOS interconnects is calculated through capacitive loss while for the spin-wave transmitter, this is obtained from the above-mentioned spin-wave power loss evaluation. Incidentally, for CMOS on-chip wirings, the resistive contribution to energy consumption would be \(\:1.44\times\:{10}^{-2}\:fJ/bit\), which is also higher than spin-wave interconnects by a factor of 1040 (4 Gbps) and 787 (10 Gbps). Detailed calculations can be found in Methods.

The bandwidth density for both CMOS on-chip wiring and spin-wave waveguide are comparable. However, CMOS devices obviously deliver information more swiftly because the electric signal propagation speed, which is approximately the speed of light, is much faster than that detected in our magnon system (\(\:{\sim2*10}^{3}m/s\)). Overall, this comparison suggests the great potential of magnonics for supplanting CMOS devices, particularly where energy dissipation limits device performance, as is common.

Tuning magnetic properties

For all the results presented so far, an applied field \(\:{H}_{y}=950\:Oe\) is used, which is the minimum field needed to saturate the sample. We have examined higher fields to see if the 10 Gbps transmission behavior can be improved. Figure 7a presents the dispersion relation curves under an applied field of \(\:950,\:2000,\:4000,\:5000,\:6000\) and \(\:7500\:Oe\) respectively. Again, an equal width and thickness of \(\:50\:nm\) is used here. It turns out that increasing \(\:{H}_{y}\) will simply move the dispersion curve up with regard to the frequency axis without drastically changing its shape. The 10 Gbps transmission test is then performed under multiple applied field values and two different carrier frequencies, \(\:40\:GHz\) and \(\:50\:GHz\), as indicated by the dashed rectangle in Fig. 7a. The corresponding intra-chip level propagation lengths are shown as the colored circles in Fig. 7b. The propagation length contour map, which gives a more comprehensive view of the device performance in this region, can then be obtained by interpolating these data points (see Methods). The best result appears near the top right corner, where \(\:{H}_{y}=5000\:Oe\:and\:{f}_{carrier}=50\:GHz\). This agrees with the previous observation on the 4 Gbps results, where the performance peaks when the carrier frequency is about 5 times of the data rate. Spin-wave excitation also benefits from this high applied field since a smaller wavevector, or a larger wavelength, is needed. Nonetheless, this high frequency along with the high applied field could be a burden considering the small gain in propagation length.

The effect of applied field and exchange coupling effect on dispersion relation and transmission performance. (a) Dispersion curves under different applied fields. (b) Contour map of intra-chip level propagation lengths in the dashed rectangle in a. Carrier frequency ranges from 40 GHz to 50 GHz. A data rate of 10 Gbps is used. (c) Dispersion curves under different exchange coupling strength. (d) Contour map of intra-chip level propagation lengths in the dashed rectangle in (c). Carrier frequency ranges from 15 to 24 GHz. A data rate of 4 Gbps is used. Contours in b and d are only a guide to the eye. The colored circles denote raw data points.

On the other hand, if we operate at \(\:40\:GHz\), which reduces the excitation difficulty, a local maximum is seen near \(\:{H}_{y}=4000\:Oe\). Compared with the low propagation lengths around the bottom right corner of Fig. 7b, this reveals another advantage of higher applied field: it could help stabilize the spin-wave propagation against thermal fluctuations and demagnetization effects. However, if we keep increasing the applied field, the transmission performance deteriorates quickly, as can be seen from the bottom left corner of Fig. 7b. This can be easily explained by the worse linearity of the dispersion curve under higher applied fields when the \(\:{f}_{carrier}\) is fixed. The ALU-level propagation lengths are also investigated, which present an almost same trend (see Supplementary Note 3).

Since the utilized spin-waves are all exchange-dominated ones, the exchange coupling effect shall play a critical role here for both 4 Gbps and 10 Gbps, and also for any other data rates. Thus, we want to aggressively vary this property so that we could understand this magnetic system from a broader view. In order to do that, we reduce the saturation magnetization by a factor of up to \(\:2.5\). This equivalently enhances the exchange coupling strength because it is proportional to \(\:\frac{1}{{M}_{S}}\). Figure 7c compares the dispersion curves with a larger exchange coupling effect that is \(\:133\text{\%},\:167\text{\%},\:200\text{\%}\) and \(\:250\text{\%}\) of the original value. An equal width and thickness of \(\:50\:nm\) is adopted. Clearly, at high \(\:{k}_{x}\) region, a stronger exchange coupling effect would bend the dispersion curves towards higher frequencies, increasing the spin-wave group velocity and slightly improving the dispersion linearity. Transmission tests are then performed under various exchange coupling strengths to prove these benefits, as marked by the dashed rectangle in Fig. 7c. A data rate of 4 Gbps is used and the carrier frequency ranges from 15 to 24 GHz. Similarly, the intra-chip level propagation lengths along with the interpolated contour map are displayed in Fig. 7d. A peak appears at the left central part of the contour map, indicating that a stronger exchange coupling effect, along with a proper carrier frequency (\(\:5\times\:data\:rate\)), favors a better propagation performance. Specifically, the intra-chip level propagation length can be increased to as large as \(\:8500\:nm\), which is \(\:\sim50\text{\%}\) higher than that under an ordinary exchange strength. This study could serve as guidance in searching for new materials, with stronger exchange coupling effect than YIG, that could potentially make better spin-wave transmitters. An example of such material is europium garnet41.

To summarize, we have proposed a high data rate spin-wave transmitter design. Our device is capable of conveying complex information at a high data rate of 4 Gbps while maintaining excellent signal quality (\(\:BER<{10}^{-6}\)) over a long distance of \(\:6.6\:\mu\:m\). ASK modulation technique is used. The dispersion relation of the magnetic waveguide is studied and an optimal system configuration is determined, where the sample is in-plane transversely saturated with respect to the waveguide long axis and spin-waves propagate longitudinally along the waveguide. Dispersion spreading is found to be the main cause of signal distortion. We have overcome this issue by selecting the appropriate carrier frequency and data rate. The input and output of our device can be either magnonic or electric signals. For the latter case, ASK signal demodulation and detection circuits are described. SNR and BER are calculated in order to characterize our device performance. Propagation lengths for various operating situations are defined and calculated. Properly increasing the sample size is shown to be beneficial. The role of carrier frequency is explained, which defines the modulation and decay boundaries. A carrier frequency that is around 5 times of data rate is empirically found to be the best choice. Based on these, an ultra-high data rate of 10 Gbps transmission scheme is found to be achievable. A comparison to modern CMOS on-chip interconnects shows that our device is much more energy efficient by a factor of more than \(\:{10}^{4}\). A higher applied field would improve the performance, but not significantly. Better material candidates than YIG are anticipated through a study on the exchange coupling effect. Our work suggests the possibility of high data rate spin-wave-based computation and also provides a detailed guide for experimentalists (See Supplementary Note 4) on how to design a proper waveguide and find the best operating spot to meet data rate requirements.

Methods

System configuration and simulation setup

All the simulations in this paper are conducted by using a home-grown GPU-based parallel micromagnetics solver. The YIG waveguide is discretized into a \(\:8192\times\:8\times\:1\) grid with each cell having a size of \(\:5\times\:6.25\times\:50\:{nm}^{3}\). Here we select a cell length \(\:dx=5\:nm\) that is much smaller than the exchange length \(\:{l}_{ex}=\sqrt{\frac{{A}_{ex}}{2\pi\:{M}_{s}^{2}}}\approx\:16.28\:nm\) of this YIG waveguide42,43, where an exchange coupling constant \(\:{A}_{ex}=3.5\times\:{10}^{-7}\frac{erg}{cm}\) and a saturation magnetization \(\:{M}_{s}=145\frac{emu}{{cm}^{3}}\) are typically used, so that we could accurately obtain details on spin-waves with small wavelength \(\:\lambda\:\) and high wavevector \(\:{k}_{x}\). This 2-dimensional (2D) discretization method is proved to be trustworthy and efficient by a 3D and 1D discretization test (see Supplementary Note 5).

The Runge-Kutta 4th order method is used to numerically solve the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert (LLG) equation:

We use a gyromagnetic ratio γ of \(\:1.77\times\:{10}^{7}{s}^{-1}{Oe}^{-1}\) and a damping constant α of \(\:0.00014\). The effective field \(\:{\user2{H}}_{\user2{e}\user2{f}\user2{f}}\) contains applied bias field \(\:{\user2{H}}_{\user2{a}\user2{p}\user2{p}}\), exchange coupling field \(\:{\user2{H}}_{\user2{e}\user2{x}}\), demagnetization field \(\:{\user2{H}}_{\user2{d}\user2{e}\user2{m}\user2{a}\user2{g}}\) and thermal fluctuation field \(\:{\user2{H}}_{\user2{t}\user2{h}\user2{e}\user2{r}\user2{m}\user2{a}\user2{l}}\). For the \(\:{\user2{H}}_{\user2{e}\user2{x}}\) field calculation, we only consider the nearest neighbor interactions. No periodic boundary condition is applied. The demagnetization field \(\:{\user2{H}}_{\user2{d}\user2{e}\user2{m}\user2{a}\user2{g}}\) is obtained by calculating the convolution of the demagnetizing tensor and the magnetization using fast Fourier Transform (FFT)44,45,46. A dipole approximation is applied for the far field tensor calculation to minimize error caused by the non-cubic cell shape47. Thermal fluctuation field \(\:{\user2{H}}_{\user2{t}\user2{h}\user2{e}\user2{r}\user2{m}\user2{a}\user2{l}}\) is generated based on a Gaussian distribution48 with a standard deviation \(\:\sigma\:=\sqrt{\frac{2{k}_{B}T\alpha\:}{\gamma\:V{M}_{s}dt}}\), where \(\:{k}_{B}\) is the Boltzmann constant and \(\:V\) is the cell volume. The simulation time step \(\:dt=50\:fs\) and room temperature is typically assumed (T = 300 K). The total simulation time ranges from \(\:30\sim36\:ns\) (long enough for the spin-waves to reach the other end) and the system is sampled every 50 time steps. The damping constant of the cells in the absorbing region linearly increases from 0.00014 to 0.96014 with an interval of 0.03. We use compute unified device architecture (CUDA) to exploit GPUs and accelerate the solver thanks to the parallel nature of magnetic systems26 and the powerful CUDA FFT (cuFFT) library which can drastically speed up the \(\:{H}_{demag}\) convolution calculation.

The magnon excitation from the transmitter is simulated by forcing the cells on the emitting end of the waveguide to precess coherently along a certain axis at an input-dependent frequency. The precession angle is set to be \(\:10^\circ\:\) in order to avoid nonlinear relaxation processes and thus allow better transmission46.

Dispersion relation

In order to obtain the dispersion relation, the magnetic system is allowed to relax from a slightly disturbed initial state under the applied bias field for 30 ns, which is sufficient for the system to reach the steady state. The initial state is defined as such: spins are aligned along the applied field direction with a randomized deviation in both \(\:\theta\:\) and \(\:\varphi\:\) with a standard deviation of \(\:0.5^\circ\:\). The spatial magnetization data are recorded every 50 simulation time steps, which are then Fourier transformed in space and time and converted into the frequency and wavevector domain. Then, for each wavevector, the main frequency, which has the maximum Fourier Transform amplitude, is found and thus the dispersion relation (main frequency vs. wavevector) can be obtained. The dispersion relation in our case is, in fact, the main frequency vs. \(\:{k}_{x}\) curve, which can be easily obtained from the original dispersion relation by setting \(\:{k}_{y}=0\).

Spin-wave transmitter power loss calculation

The main magnetization component \(\:{M}_{y}\) data are used here to calculate the spin-wave decay rate since it’s easier to extract their amplitude change. A carrier frequency of \(\:18\:GHz\) is used. In order to eliminate the spatial spin-wave perturbation, the waveguide is divided into several long boxes with a length of 575 nm, which is much longer than the spin-wave wavelength λ. Then the \(\:{M}_{y}\) data are averaged over this box length and presented in Fig. 2b as blue circles. An exponential fitting is performed on the averaged \(\:{M}_{y}\) data to obtain the spin-wave decay function over distance \(\:x\)9,10,49,50: \(\:{M}_{y}={M}_{s}-a{e}^{bx}\) with \(\:a=2.139\) and \(\:b=-1.765\times\:{10}^{-5}\). The red curve in Fig. 2b shows the fitting result. Spin-wave energy dissipation can then be calculated through the magnon number loss: \(\:\varDelta\:E={E}_{magnon}\times\:\varDelta\:n\), where \(\:{E}_{magnon}=\hslash\:\omega\:\) is the energy of a single magnon with \(\:\omega\:=2\pi\:f\) and \(\:\varDelta\:n\) is the change in magnon numbers. Since the existence of one magnon gives a magnetization decrement that would result from the reversal of one spin32,51, which equals \(\:2{\mu\:}_{B}\) with \(\:{\mu\:}_{B}\) being the Bohr magneton, \(\:\varDelta\:n\) can be expressed as \(\:\varDelta\:n=\frac{\varDelta\:M\times\:{V}_{box}}{2{\mu\:}_{B}}\), where \(\:\varDelta\:M={M}_{s}-{M}_{y}=a{e}^{bx}\) and \(\:{V}_{box}\) is the volume of the above mentioned box. Based on these, we can estimate this spin-wave device power loss at any given distance as long as the corresponding propagation time \(\:\varDelta\:t\) is known: \(\:{P}_{loss}^{magnonic}=\frac{\varDelta\:E}{\varDelta\:t}\). Here, we capture \(\:\varDelta\:n\) and \(\:\varDelta\:t\) values at a distance \(\:l=4\:\mu\:m\): \(\:\varDelta\:n=11,259,\:\varDelta\:t=2.37\:ns\), and get \(\:{P}_{loss}^{magnonic}=5.6658\times\:{10}^{-11}\:Watts\). Note that for a PRBS, this power loss would be slightly higher due to the broader frequency spectrum. Details can be found in Supplementary Note 6.

Demodulation methods

The ASK-modulated signal is demodulated using a standard envelope extraction method36,37. A low-pass filter is first applied to the target signal to remove thermal noise. A filter threshold of \(\:{f}_{carrier}+data\:rate\) is used here to filter out as much noise as possible while keeping the main lobe in the signal spectrum intact. The signal is then downsampled with a downsample factor of 6 and squared. Another low-pass filter is then used to remove all the high frequency signals so that the low frequency envelope can be extracted. The filter threshold here is equal to half of the data rate. The square root of the signal has to be taken and a factor of 2 needs to be multiplied in order to keep the amplitude correct.

SNR and BER calculation

For SNR calculations, we transmit 36 PRBS signals with different thermal fluctuation noises. Magnetization data are collected every \(\:250\:nm\) along the waveguide in order to check how the output signal degrades along the distance. At a certain distance, the demodulation process will convert the 36 transmitted signals into analog signals. For each analog signal, the DC component is first removed by subtracting its time average. In order to better simulate the realistic readback process, where the use of the downsampler and low-pass filters also affects the signal quality, SNR is calculated based on an ensemble waveform analysis method52. The following equation is used:

The average signal, or the noise-free signal, is obtained by averaging these 36 signals. Then, signal power is defined as the total sum of squares of the average signal while noise power is obtained by calculating the variance of these signals.

For BER calculation, these 36 analog signals are sampled with an interval that is equal to the bit time length. For 4 Gbps, this is \(\:\frac{1}{4*{10}^{9}}=0.25*{10}^{-9}\:s=0.25\:ns\) while for 10 Gbps, this is \(\:\frac{1}{10*{10}^{9}}={10}^{-10}\:s=0.1\:ns\). These sampled signals are then further converted into digital signals so that a decision circuit, such as a threshold detector or a Viterbi detector53,54,55, can be applied and the number of error bits can be obtained. A total of 1116 bits are received, defining a BER resolution of \(\:8.96\times\:{10}^{-4}\). In order to further obtain BER data in the ultra-low regime, which would otherwise require unreasonably large simulation resources, the SNR-BER relation is fitted to the following equation53,56 using the nonlinear least square method:

which provides exceptional fitting results, as shown in Figs. 4c and 6c as the dots and dashed lines. The BER curve can then be extrapolated according to SNR data based on this fit, as presented in Figs. 4d and 6d. A monotonic dependence on propagation distance is seen for both SNR and BER.

Performance comparison

The energy consumption per bit can be derived based on the spin-wave power loss rate: \(\:{E}_{bit}^{magnonic}=\frac{{P}_{loss}^{magnonic}}{data\:rate}\). For CMOS on-chip interconnects, since transmission of one bit means charging one capacitor57, the energy dissipation is evaluated through the capacitive loss40: \(\:{E}_{bit}^{interconnect}={C}_{ic}{V}_{dd}^{2}\). The interconnect capacitance \(\:{C}_{ic}={c}_{wire}{l}_{ic}\) has a value of \(\:504\:aF\), where \(\:{c}_{wire}=126\:aF/\mu\:m\) and the interconnect length \(\:{l}_{ic}\) is assumed to be \(\:4\:\mu\:m\). A power supply voltage \(\:{V}_{dd}=0.7\:V\) is used according to the 2022 International Roadmap for Devices and Systems58. The resistive power loss, on the other hand, is estimated by using: \(\:{P}_{loss}^{resistive}={I}^{2}R={J}^{2}{A}^{2}\frac{\rho\:l}{A}={J}^{2}A\rho\:l\), where \(\:J\) is the current density, \(\:A\) and \(\:l\) are the cross-sectional area and length of the wire, \(\:\rho\:\) is the resistivity. Copper is considered here as the material for the interconnect wire, which is dominantly used in the semiconductor industry59,60. A current density of \(\:2\times\:{10}^{6}A*{cm}^{-2}\) is used61. The cross-sectional area is assumed to be \(\:10\times\:10\:{nm}^{2}\) based on the current integrated circuits (IC) design paradigm59,60. The length of the wire is assumed as \(\:4\:\mu\:m\) again. A thorough study on interconnect material conducting properties is presented by Daniel Gall59, which gives a reasonable resistivity of \(\:36\:\mu\:{\Omega\:}*cm\) for this geometry. All these parameters finalize a power dissipation rate \(\:{P}_{loss}^{resistive}=5.76\times\:{10}^{-8}\:Watts\). The energy consumption per bit is then simply: \(\:\frac{{P}_{loss}^{resistive}}{data\:rate}=\frac{5.76\times\:{10}^{-8}}{4\:Gbps}=1.44\times\:{10}^{-2}\:fJ/bit\).

The bandwidth density is obtained by simply dividing the data rate by device pitch. A data rate of 4 Gbps is assumed here for CMOS interconnects while our spin-wave transmitter could reach a data rate of 10 Gbps. Modern finFET devices have a gate pitch of 48 nm58. Our spin-wave waveguide is designed to have a pitch of twice its width (\(\:100\:nm\)) so that neighboring interactions are greatly reduced. This distance is estimated using spacing loss theory62, namely stray field is proportional to \(\:{e}^{-kd}\). Note that for the leading edge 3–4 GHz CPU clock rates, the actual data rate could be higher than 4 Gbps depending on different chip architectures.

For the propagation latency estimation, a wire length of \(\:0.3\:\mu\:m\) is assumed for both cases. The CMOS interconnect delay time is calculated by: \(\:{t}_{interconnect}=\frac{0.7{C}_{ic}{V}_{dd}}{{I}_{dev}}\), where \(\:{I}_{dev}=1.083\times\:{10}^{-4}\:A\) is the device on-current40. \(\:{C}_{ic}\) and \(\:{V}_{dd}\) have the same values as those used in the energy consumption calculations. The spin-wave delay time and group velocity can be extracted directly from the simulation.

Propagation length contour map

For each specific case (with a certain \(\:{H}_{y}\), \(\:{f}_{carrier}\) or exchange coupling effect), the transmission test is performed. Similarly, 36 signals are transmitted and SNR and BER results are calculated. The two propagation lengths are obtained from the SNR-BER curve fitting. These data are displayed as colored circles on the dashed dispersion curves in Fig. 7b and d. A surface fitting is then done by smoothly interpolating (and also extrapolating) these scattered data points63. The contour lines can thus be easily drawn based on this modeled surface.

Data availability

The simulation data generated for this work are available from the corresponding author upon request. The CUDA codes used to simulate spin-wave transmission and the MATLAB codes used for data processing are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Chumak, A. V. et al. Roadmap on spin-wave computing. IEEE Trans. Magn.58, 1–72 (2022).

Chumak, A. V., Vasyuchka, V. I., Serga, A. A. & Hillebrands, B. Magnon spintronics. Nat. Phys.11, 453–461 (2015).

Mahmoud, A. et al. Fan-out enabled spin wave majority gate. AIP Adv.10, 1–6 (2020).

Papp, Á., Porod, W. & Csaba, G. Nanoscale neural network using non-linear spin-wave interference. Nat. Commun.12, 1–8 (2021).

Wang, Q. et al. Reconfigurable nanoscale spin-wave directional coupler. Sci. Adv.4, 1–13 (2018).

Salikhov, R. et al. Coupling of terahertz light with nanometre-wavelength magnon modes via spin–orbit torque. Nat. Phys.19, 529–535 (2023).

Hortensius, J. R. et al. Coherent spin-wave transport in an antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys.17, 1001–1006 (2021).

Houshang, A. et al. Spin transfer torque driven higher-order propagating spin waves in nano-contact magnetic tunnel junctions. Nat. Commun.9, 1–6 (2018).

Demidov, V. E., Urazhdin, S. & Demokritov, S. O. Direct observation and mapping of spin waves emitted by spin-torque nano-oscillators. Nat. Mater.9, 984–988 (2010).

Madami, M. et al. Direct observation of a propagating spin wave induced by spin-transfer torque. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 635–638 (2011).

Divinskiy, B. et al. Excitation and amplification of spin waves by spin–orbit torque. Adv. Mater.30, 1–6 (2018).

Ren, H. et al. Hybrid spin hall nano-oscillators based on ferromagnetic metal/ferrimagnetic insulator heterostructures. Nat. Commun.14, 1–7 (2023).

Duan, Z. et al. Nanowire spin torque oscillator driven by spin orbit torques. Nat. Commun.5, 1–7 (2014).

Dvornik, M., Awad, A. A. & Åkerman, J. Origin of magnetization auto-oscillations in constriction-based spin hall nano-oscillators. Phys. Rev. Appl.9, 14017 (2018).

Papp, A., Porod, W. & Csaba, G. Hybrid yttrium iron garnet-ferromagnet structures for spin-wave devices. J. Appl. Phys.117, 17E101 (2015).

Balinsky, M. et al. Modulation of the spectral characteristics of a nano-contact spin-torque oscillator via spin waves in an adjacent yttrium-iron garnet film. IEEE Magn. Lett.7, 46–49 (2016).

Bonetti, S., Muduli, P., Mancoff, F. & Åkerman, J. Spin torque oscillator frequency versus magnetic field angle: The prospect of operation beyond 65 GHz. Appl. Phys. Lett.94, 102507 (2009).

Sluka, V. et al. Emission and propagation of 1D and 2D spin waves with nanoscale wavelengths in anisotropic spin textures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 328–333 (2019).

Verba, R., Carpentieri, M., Finocchio, G., Tiberkevich, V. & Slavin, A. Excitation of propagating spin waves in ferromagnetic nanowires by microwave voltage-controlled magnetic anisotropy. Sci. Rep.6, 1–9 (2016).

Chen, J. et al. Reconfigurable spin-wave interferometer at the nanoscale. Nano Lett.21, 6237–6244 (2021).

Fischer, T. et al. Experimental prototype of a spin-wave majority gate. Appl. Phys. Lett.110, 152401 (2017).

Wang, Q. et al. A magnonic directional coupler for integrated magnonic half-adders. Nat. Electron.3, 765–774 (2020).

Vogel, M. et al. Control of spin-wave propagation using magnetisation gradients. Sci. Rep.8, 1–10 (2018).

Brächer, T. et al. Time- and power-dependent operation of a parametric spin-wave amplifier. Appl. Phys. Lett.105, 232409 (2014).

Heinz, B. et al. Propagation of spin-wave packets in individual nanosized yttrium iron garnet magnonic conduits. Nano Lett.20, 4220–4227 (2020).

Venugopal, A., Qu, T. & Victora, R. H. Parallel computations based micromagnetic solver and analysis tools for magnon-microwave interaction studies. IEEE J. Multisc. Multiphys. Comput. Tech.6, 239–248 (2021).

Qu, T., Venugopal, A. & Victora, R. H. Dependence of nonlinear response and magnon scattering on material properties. J. Appl. Phys.129, 163903 (2021).

Qu, T. et al. Nonlinear magnon scattering mechanism for microwave pumping in magnetic films. IEEE Access.8, 216960–216968 (2020).

Venugopal, A., Qu, T. & Victora, R. H. Nonlinear parallel-pumped FMR: three and four magnon processes. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech.68, 602–610 (2020).

Hsu, W. H. & Victora, R. H. Heat-assisted magnetic recording—Micromagnetic modeling of recording media and areal density: A review. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.563, 169973 (2022).

Bhaskar, U. K., Talmelli, G., Ciubotaru, F., Adelmann, C. & Devolder, T. Backward volume vs Damon-Eshbach: A traveling spin wave spectroscopy comparison. J. Appl. Phys.127, 033902 (2020).

Rezende, S. M. Fundamentals of Magnonics, pp. 135–153, 31–42 (Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2020).

Brächer, T., Boulle, O., Gaudin, G. & Pirro, P. Creation of unidirectional spin-wave emitters by utilizing interfacial Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B. 95, 1–13 (2017).

Wang, Q. et al. Spin pinning and spin-wave dispersion in nanoscopic ferromagnetic waveguides. Phys. Rev. Lett.122, 247202 (2019).

Okawara, H. DSP-based testing-fundamentals 50 PRBS (pseudo random binary sequence). ADVANTEST Corporation (2013). https://www3.advantest.com/documents/11348/3e95df23-22f5-441e-8598-f1d99c2382cb

Pozar, D. M. Microwave and RF Design of Wireless Systems, pp. 303–320 (Wiley, 2001).

Mathworks MATLAB DSP System Toolbox User’s Guide R2023b. 4–472 (2023).

Mihalceanu, L. et al. Temperature-dependent relaxation of dipole-exchange magnons in yttrium iron garnet films. Phys. Rev. B. 97, 1–9 (2018).

Serha, R. O. et al. Magnetic anisotropy and GGG substrate stray field in YIG films down to millikelvin temperatures. Npj Spintron. 2, 29 (2024).

Nikonov, D. E. & Young, I. A. Overview of beyond-CMOS devices and a uniform methodology for their benchmarking. Proc. IEEE 101, 2498–2533 (2013).

Wolf, W. P. & Vleck, J. H. Van. Magnetism of europium garnet. Phys. Rev.118, 1490–1492 (1960).

Abo, G. S. et al. Definition of magnetic exchange length. IEEE Trans. Magn.49, 4937–4939 (2013).

Wang, S., Wei, D. & Gao, K. Z. Limits of discretization in computational micromagnetics. IEEE Trans. Magn.47, 3813–3816 (2011).

Newell, A. J., Williams, W. & Dunlop, D. J. A generalization of the demagnetizing tensor for nonuniform magnetization. J. Geophys. Res.98, 9551–9555 (1993).

Hayashi, N., Saito, K. & Nakatani, Y. Calculation of demagnetizing field distribution based on fast Fourier transform of convolution. Japan. J. Appl. Phys. Part. 1 Regul. Pap Short. Notes Rev. Pap. 35, 6065–6073 (1996).

Dobin, A. Y. & Victora, R. H. Intrinsic nonlinear ferromagnetic relaxation in thin metallic films. Phys. Rev. Lett.90, 4 (2003).

Donahue, M. J. Accurate computation of the demagnetization tensor. https://math.nist.gov/~MDonahue/talks/hmm2007-MBO-03-accurate_demag.pdf

Morgan, S. M. & Victora, R. H. Use of square waves incident on magnetic nanoparticles to induce magnetic hyperthermia for therapeutic cancer treatment. Appl. Phys. Lett.97, 093705 (2010).

Qin, H., Hämäläinen, S. J., Arjas, K., Witteveen, J. & Van Dijken. Propagating spin waves in nanometer-thick yttrium iron garnet films: dependence on wave vector, magnetic field strength, and angle. Phys. Rev. B. 98, 1–8 (2018).

Qin, H. et al. Nanoscale magnonic Fabry-Pérot resonator for low-loss spin-wave manipulation. Nat. Commun.12, 2293 (2021).

O’Handley, R. C. Modern Magnetic Materials: Principles and Applications, pp. 100–102 (Wiley, 2000).

Hernandez, S. et al. Using ensemble waveform analysis to compare heat assisted magnetic recording characteristics of modeled and measured signals. IEEE Trans. Magn.53, 1–6 (2017).

Jiao, Y., Wang, Y. & Victora, R. H. A study of SNR and BER in heat-assisted magnetic recording. IEEE Trans. Magn.51, 11–14 (2015).

Liu, Z., Jiao, Y. & Victora, R. H. Composite media for high density heat assisted magnetic recording. Appl. Phys. Lett.108, 232402 (2016).

Hsu, W. H. & Victora, R. H. Rotated read head design for high-density heat-assisted shingled magnetic recording. Appl. Phys. Lett.118, 072406 (2021).

Lynch, R., Kurtas, E. M., Kuznetsov, A., Yeo, E. & Nikolic, B. The search for a practical iterative detector for magnetic recording. IEEE Trans. Magn.40, 213–218 (2004).

Nikonov, D. E. & Young, I. A. Benchmarking of beyond-CMOS exploratory devices for logic integrated circuits. IEEE J. Explor. Solid-State Comput. Devices Circ. 1, 3–11 (2015).

The International Roadmap for Devices and Systems. Executive summary. Inst. Electr. Electron. Eng. 44–45 (2022). https://irds.ieee.org/editions/2022

Gall, D. The search for the most conductive metal for narrow interconnect lines. J. Appl. Phys.127, 050901 (2020).

Gall, D. et al. Materials for interconnects. MRS Bull.46, 959–966 (2021).

Vyas, A. A., Zhou, C. & Yang, C. Y. On-chip interconnect conductor materials for end-of-roadmap technology nodes. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 17, 4–10 (2018).

Bertram, H. N. Theory of Magnetic Recording, pp. 38–44 (Cambridge University Press, 1994).

D’Errico, J. Surface fitting using gridfit (2023). https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/8998-surface-fitting-using-gridfit). MATLAB Cent. File Exch..

Acknowledgements

Kun Xue would like to acknowledge Aneesh Venugopal, Weiheng-Hsu, Tao Qu, Wen Zhou, Yijia Liu, Runzi Hao and Yipeng Jiao for fruitful discussions and useful guidance. We are also grateful for constructive suggestions from Ian A. Young. We thank Yu (Kevin) Cao for a useful introduction to CMOS interconnects. The authors acknowledge the support and funding from the Center for Micromagnetics and Information Technologies (MINT) at the University of Minnesota. The authors also acknowledge the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute (MSI) at the University of Minnesota for providing computation resources that contributed to the research results reported within this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R. H. V. and K. X. conceived the original idea. K. X. performed all of the work. K. X. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xue, K., Victora, R. High data rate spin-wave transmitter. Sci Rep 14, 23129 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73957-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73957-w