Abstract

Needle selection plays a pivotal role in determining the success of fine needle aspiration (FNA) procedures. Two commonly utilized puncture needles for thyroid FNA are the conventional syringe needle and the stylet needle. Syringe needles are known for their cost-effectiveness in comparison to stylet needles. This study aimed to determine if FNA with syringe needles is non-inferior to FNA with stylet needles in terms of specimen adequacy while also comparing the direct costs associated with both needle types. A total of 220 thyroid nodules from 185 patients were prospectively included in this study. The same operator performed a total of four punctures on the same nodule twice using a syringe and a stylet needle. The results of this study show that the utilization of syringe needles for thyroid FNA was non-inferior to the use of stylet needles in terms of specimen adequacy. Cost analysis revealed that syringe needle FNA was not only less expensive (CNY 500.9 versus CNY 780) but also more effective (adequacy 85.91% versus 84.55%). In summary, given the global prevalence of FNA procedures, the economic considerations are paramount, and our findings support the routine use of syringe needles in thyroid FNA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) represents the preferred diagnostic method for assessing suspicious thyroid nodules, with the initial focus being on the selection of the optimal puncture needle. Within the realm of thyroid FNA, two primary types of puncture needles are commonly employed: the conventional syringe needle, devoid of a stylet1,2,3, and the stylet-equipped puncture needle4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Some reports4,5,6,7,8 have advocated the adoption of stylet needles in thyroid FNA, suggesting that the presence of a stylet prevents the needle lumen from potential contamination by extraneous non-lesion materials, including blood, prior to penetration into the targeted lesion. This hypothesis implies an enhancement in specimen quality using stylet needles. However, it is worth noting that in other areas of FNA, such as gastrointestinal and respiratory endoscopic FNA, the value of stylets has come under scrutiny in recent years. An increasing body of literature12,13,14,15,16,17,18 has raised doubts regarding the efficacy of stylets in improving specimen quality and has, in some instances, even associated them with a decline in specimen quality19. Furthermore, stylet needles are comparatively costly when compared to syringe needles, potentially imposing a substantial financial burden on patients undergoing FNA. In the context of the millions of patients worldwide who undergo FNA for thyroid nodules each year20, the issue of cost assumes paramount significance.

Given the ongoing debate concerning the value of stylet needles, we conducted a preliminary study21 to assess the impact of using needles with or without stylets on specimen sampling. In this study, we compared puncture needles (Fig. 1) of identical material, length, and gauge to elucidate whether the presence of a stylet improved specimen quality. Our preliminary findings revealed that the use of a needle stylet did not yield an improvement in specimen quality. However, it should be borne in mind that these results do not directly address the comparative merits and drawbacks of syringe needles versus stylet needles in specimen sampling, as differences in material, needle morphology, length, and other factors exist between the two (Fig. 2). Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to directly compare whether syringe needles are non-inferior to stylet needles in terms of specimen adequacy for thyroid FNA.

Methods

Patients and ethics approval

This study prospectively enrolled patients with thyroid nodules who underwent FNA between November 2022 and December 2023. Inclusion criteria comprised (1) age 18 years and older, (2) the ability to provide informed consent, and (3) ultrasound indications of thyroid nodules. Exclusion criteria encompassed (1) undergoing anticoagulation therapy, (2) cystic nodules, and (3) inability to provide informed consent. Ethical approval was obtained from the hospital ethics committee (Approval No: 2022-80), and written informed consent was secured from all participating patients. The methods in this study were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. This clinical trial has been registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (Registration number ChiCTR2200065318, first registration on 02/11/2022).

Randomization

Each nodule underwent four punctures, twice with a conventional syringe needle and twice with a stylet needle. To mitigate the potential impact of bleeding from the previous puncture on subsequent specimens, nodules were randomly allocated into two groups. One group was initially punctured with a stylet needle, resulting in the sequence of punctures being stylet needle, syringe needle, stylet needle, and syringe needle for this group of nodules. The other group was initially punctured with a syringe needle, leading to the sequence of punctures being syringe needle, stylet needle, syringe needle, and stylet needle for this group of nodules. The random sequence of punctures using stylet or syringe needles was generated by a computer program and sealed in an opaque envelope. The envelope was opened by the operator immediately before each puncture, following patient confirmation of enrollment.

FNA procedure

All FNAs were performed by the same operator using an ultrasound scanner (M9, Mindray, Shenzhen, China) equipped with a 7.5–15 MHz linear array transducer. A 25G disposable syringe needle (RWLB, Lelun, Changzhou, China) and a 25G disposable stylet needle (CCZA, Leapmed, Suzhou, China) were used for syringe and stylet needle FNAs, respectively. Both needle types are illustrated in Fig. 2. To prevent tumor needle tract metastasis, needles were not reused. Patient medical records included information about the number, echogenicity, composition, Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (TIRADS) score, long diameter, and calcification of the punctured nodules. In cases of multiple nodules, cytologic examination was performed on suspicious nodules. In the absence of suspicious nodules, the dominant (largest) nodule was sampled.

FNA was conducted following previously described procedures21. Each nodule was punctured four times, twice with a stylet needle and twice with a syringe, in a predetermined order. When using a stylet needle for puncture, the stylet was removed under ultrasound guidance upon puncture into the nodule, and the needle was withdrawn after rapid back-and-forth movement within the nodule for 15–20 times or when sample material was visible at the center of the needle. When using a syringe needle for a puncture, the steps mirrored those for a stylet needle, except for the removal of the stylet. Negative pressure aspiration was not employed in either needle FNA, and no on-site adequacy assessment was conducted.

After each puncture, a 5-mL air-filled syringe was used to expel the contents of the needle lumen onto a clean slide. Each puncture produced one slide specimen, which was labeled in the order of puncture as slides A1, B1, A2, and B2. This approach ensured that the choice of stylet or syringe needle for the first puncture was randomized, preventing potential bias on the part of the pathologist. Specimens were air-dried, fixed in 95% alcohol, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Cytologic evaluation

Five pathologists evaluated all slides using the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology (TBSRTC)22, with each patient’s slides evaluated by the same pathologist. Adequate specimens should include at least six groups of benign follicular cells, with each group containing a minimum of ten cells. Moreover, specimens are considered sufficient for diagnosis if they contain an adequate number of typical cells, atypical cells, or large amounts of colloid, even if the required six groups of follicular cells are not identified. Each nodule’s two stylet needle specimens and two syringe needle specimens were independently assessed as whole specimens, meaning that slides A1 and A2 constituted specimens for “Nodule A”, while slides B1 and B2 were specimens for “Nodule B”. A nodule was considered inadequate if both stylet needle specimens were deemed inadequate. Similarly, the syringe needle specimen of a nodule was classified as inadequate if both syringe needle specimens were found to be inadequate.

Outcome variables

The primary outcome was the adequacy of specimens obtained with both needle FNAs. Secondary outcomes included the concordance of specimen adequacy between both needle FNAs, sensitivity, specificity, and the cost of both needle FNAs. Specimen adequacy was defined as the percentage of non-TBSRTC I diagnoses, i.e., TBSRTC II, III, IV, V, and VI diagnostic categories, as a proportion of the total number of specimens.

Costs were assessed in Chinese Yuan (CNY) and comprised anesthesia fees, ultrasound guidance costs, procedure fees, puncture needle costs, and pathology fees. The total cost of FNA for each needle, the cost of a single FNA, and the cost per adequate specimen were computed. The cost-effectiveness ratio (cost/adequacy) and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) were calculated for both needle FNAs, with adequacy serving as the effect indicator. The ICER was calculated as follows:

Where, cA is the cost of stylet needle FNA, cB is the cost of syringe needle FNA, eA is the adequacy of stylet needle FNA, and eB is the adequacy of syringe needle FNA.

Sample size estimation

Sample size estimation was carried out using PASS software (version 11). We assumed that specimen adequacy for thyroid FNA using either syringe needles or stylet needles was 85.64%, as reported in our preliminary study21. Based on this assumption, we set the non-inferiority margin at 10%, with a type 1 error of 0.025 (one-sided) and a type 2 error of 0.8. It was also assumed that 10% of enrolled nodules would require exclusion. Consequently, the final calculation determined that 214 nodules were necessary.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software (version 23) and SAS software (version 9.4). Each nodule was treated as an independent unit for statistical analysis. Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation, while categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage. Primary outcome statistics were analyzed using the Wald test, with the difference in adequacy between the two methods presented as a two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI). Syringe needle FNA was deemed non-inferior to stylet needle FNA if the lower bound of the two-sided 95% CI for the adequacy difference (syringe needle FNA minus stylet needle FNA) exceeded − 10%. Postoperative paraffin pathology was used to calculate the sensitivity and specificity of the two types of FNA, and both category V and VI specimens were treated as positive specimens, as both indicate a high likelihood of malignancy and follow the same clinical management approach (surgery was recommended), and the remaining categories were treated as negative specimens. Agreement between the adequacy of the two needle specimens was assessed using the Kappa test, with Kappa values interpreted as follows: 0.00 ~ 0.20, slight agreement; 0.21 ~ 0.40, basic agreement; 0.41 ~ 0.60, moderate agreement; 0.61 ~ 0.80, substantial agreement; and 0.80 ~ 1.00, almost complete agreement.

Results

Patients and lesions

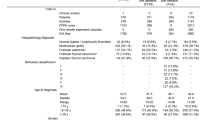

A total of 193 patients were initially recruited for the study. Eight patients were subsequently excluded: one patient was under anticoagulation therapy, five patients declined to participate, one patient had no detectable nodules, and one patient presented a solitary cystic nodule (see Fig. 3 for the recruitment flowchart). Ultimately, 185 patients (comprising 220 nodules) were enrolled in the study, with female (84.86%) predominance and a mean age of 49.51 ± 11.44 (range 18 to 76 years). Among them, 50 patients had single nodules, while 135 had multiple nodules. Among the 220 sampled nodules, 171 were hypoechoic, 42 were isoechoic, and 7 were hyperechoic. There were 166 solid nodules and 54 solid-cystic nodules. The mean nodule length was 1.40 ± 1.00 mm, ranging from 0.3 to 5.1 cm. According to the TI-RADS classification, nodules were categorized as class 2 (n = 1), class 3 (n = 67), class 4a (n = 107), class 4b (n = 36), class 4c (n = 7), and class 5 (n = 2). Calcification was associated with 111 nodules. Each nodule underwent four punctures with both a stylet needle and a syringe needle. Among the 220 nodules, 107 were randomized to be punctured initially with a stylet needle, while 113 were randomized to be punctured initially with a syringe needle. Cytologic diagnoses were as follows: malignant (TBSRTC VI) (n = 35, 15.91%), suspected malignant (TBSRTC V) (n = 34, 15.45%), follicular tumor or suspected follicular tumor (TBSRTC IV) (n = 5, 2.27%), atypical (TBSRTC III) (n = 53, 24.09%), benign (TBSRTC II) (n = 64, 29.09%), and inadequate (TBSRTC I) (n = 29, 13.18%).

Specimen adequacy, sensitivity and specificity

Out of 220 nodules, 191 (86.82%) yielded overall adequate specimens. Specifically, stylet needles produced 186 out of 220 (84.55%) adequate specimens, while syringe needles yielded 189 out of 220 (85.91%) adequate specimens. The corresponding cytologic diagnostic results for both types of needles are presented in Fig. 4.

The difference in FNA adequacy between the two needles (syringe needle minus stylet needle) was 1.36% (95% CI, -5.27–7.99%). Importantly, the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval for this adequacy difference (-5.27%) exceeded the predefined non-inferiority threshold of -10%. These results confirmed that the FNA specimen adequacy achieved with syringe needles was not inferior to that obtained with stylet needles.

In 184 out of 220 nodules, both needle specimens were deemed adequate, while in 29 nodules, both needle specimens were inadequate. Additionally, two nodules exhibited adequate stylet needle specimens but inadequate syringe specimens, and five nodules displayed adequate syringe needle specimens but inadequate stylet needle specimens. Thus, both needle types consistently demonstrated specimen adequacy in 213 nodules (96.82%) with a Kappa coefficient of 0.87. Furthermore, the two needles exhibited consistent cytological results in 186 nodules (84.55%) with a Kappa coefficient of 0.80. The consistency of cytological results for both needle types is summarized in Table 1.

Ninety-four patients underwent subsequent thyroidectomy and paraffin pathology results were obtained for 106 nodules, including 73 papillary carcinoma, 2 medullary carcinomas, and 31 benign. The sensitivity of the stylet needle FNA was 77.33% with a specificity of 90.32%. Syringe needle FNA had a sensitivity of 78.67% and a specificity of 87.09%. The difference in sensitivity and specificity between the two FNAs was not significant (P > 0.05).

Cost analysis

The cost of a single FNA session using a stylet needle was 780 CNY, whereas the cost of using a syringe needle was 500.9 CNY. This represented a 35.78% reduction in the cost of FNA with syringe needles compared to stylet needles, as indicated in Table 2. The total cost of stylet needle FNAs amounted to 171,600 CNY, while syringe needle FNAs totaled 110,198 CNY, resulting in a cost savings of 61,402 CNY with syringe needle FNAs in this group of nodules.

The cost of obtaining one adequate specimen with a stylet needle FNA was 922.58 CNY, whereas, with a syringe needle, it was 583.06 CNY. This represented a 36.80% reduction in the cost of obtaining one adequate specimen using syringe needles compared to stylet needles. In other words, the syringe needle demonstrated a lower cost-effectiveness ratio (cost/adequacy) than the stylet needle (583.06 VS 922.58). The ICER was calculated as − 20,522.06, as shown in Table 3. A negative ICER indicated that syringe needle FNA is more cost-effective.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated the non-inferiority of syringe needle FNA in terms of specimen adequacy compared to stylet needle FNA. Both needle types performed similarly in producing adequate specimens, with a high degree of consistency observed when comparing their performance at the individual lesion level. Furthermore, the cost analysis highlighted the advantages of using syringe needles in terms of cost-effectiveness.

The choice of needle for FNA is a critical decision, and in thyroid FNA, two commonly used options are conventional syringe needles without a stylet1,2,3 and puncture needles with a stylet4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Over the years, many studies4,5,6,7,8 have assessed the value of stylet needles in thyroid FNA, with claims that they enhance specimen adequacy, attributed to the stylet needle’s ability to prevent contamination of the needle lumen with blood or cystic fluid before puncturing the target lesion, ultimately leading to a more adequate specimen when the stylet is removed7,8. However, it is worth noting that these several reports4,5,6,7,8 promoting stylet needles were authored by the same investigator, and thus, the hypothesis still lacks robust supporting evidence. Furthermore, in other areas of FNA, such as gastroenterology endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) and Endobronchial ultrasonographically guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA), recent studies12,13,14,15,16,17,18 have raised doubts about the role of stylet needles. These studies have indicated that the value of stylets is primarily theoretical and, in practice, does not consistently improve specimen adequacy and can even lead to worse specimen quality19. Consequently, there is a growing call for clinicians to reevaluate the value of stylet needles. Given that stylet needles are significantly more expensive than syringe needles, their cost may not be justified if they do not substantially enhance specimen quality.

This lack of consensus regarding the value of stylet needles prompted us to conduct a preliminary study evaluating stylet needles21. Herein, we compared the impact of using or not using a stylet on specimen adequacy, using puncture needles of the same form, material, length, and gauge. The results from that study revealed that FNA without a stylet was not inferior to FNA with a stylet in terms of specimen adequacy. However, these findings did not directly address the superiority or inferiority of stylet needles versus syringe needles for specimen sampling due to differences in needle morphology, material, length, and other factors between the two. Notably, the stylet needle (5 cm) used in our study was longer than the syringe needle (3.8 cm). While a longer needle may increase the likelihood of blood coagulation in the needle lumen and susceptibility to bending, previous research4 indicated that needle length is not a major factor affecting specimen adequacy. Interestingly, needle tip morphology could potentially impact specimen adequacy, with long, pointed, and less steep tips possibly causing the drifting of sampled cells and easier capture of blood and fluids23. However, current evidence suggests that the morphology of the needle tip has limited influence on specimen adequacy, as the diagnostic outcomes of FNA are largely independent of needle morphology24. In essence, both stylet needles and syringe needles are fine needles that obtain cells by cutting the needle tip, with capillary siphonage drawing the cut cells into the needle lumen. The primary distinction between the two is the presence or absence of a stylet.

Indeed, a stylet may prevent puncture blood from entering the needle lumen before stylet removal. However, this benefit may not significantly enhance specimen quality for experienced operators. Experienced operators can often anticipate the puncture route and angle in advance, allowing for precise needle placement into the nodule with minimal adjustments. Bleeding from thyroid tissue puncture tends to occur during prolonged needle adjustments, which can lead to blood entering the needle lumen. Furthermore, the process of stylet withdrawal generates negative pressure25,26, potentially compromising specimen adequacy. When the stylet is removed after the needle enters the target nodule but before it is used to cut and collect focal cells, the negative pressure generated during stylet withdrawal may draw non-focal components such as blood and cystic fluid into the needle lumen, potentially interfering with the entry of focal cells obtained during subsequent cutting. This disadvantage was also observed in a previous EUS-FNA study19, where specimens with a stylet exhibited significantly more blood and lower specimen adequacy compared to those without a stylet.

Additionally, prior studies4,5,6,7 evaluating stylet needles did not compare both needle types on the same nodule but rather used only one needle type per nodule. This approach may introduce selection bias, such as the possibility that easier-to-puncture nodules were assigned to the experimental group. In our study, each lesion served as its own control, ensuring that variables associated with each puncture method (stylet needle FNA or syringe needle FNA) were essentially identical, except for the choice of puncture needle. Gimeno-García et al.27 deemed self-control (simultaneous use of both techniques on the same nodule) to be the best method for controlling all variables potentially influencing the results. However, self-control is not without limitations, particularly regarding the possibility of bleeding from the previous puncture affecting the subsequent puncture specimen28. To mitigate this concern, we randomized the first puncture for each nodule, alternating between stylet needle and syringe needle. Half of the patients were randomized to undergo the first puncture with a stylet needle, while the other half began with a syringe needle (the number of initial punctures with each needle type was randomized and evenly distributed). Therefore, our study design aimed for comparability, objectivity, and accuracy.

Economic evaluation has indeed become a crucial decision-making tool for healthcare systems. Stylet needles are generally more expensive than syringe needles. In our study, the stylet needle cost was 140 CNY, while the syringe needle cost was 0.45 CNY, representing a 311-fold price difference. Other commonly used stylet needles reported in the literature4,5,6,7 cost approximately $1.33–3, whereas corresponding syringe needles cost $0.19, resulting in price differences of 7–15.8 times. The increase in cost should theoretically yield increased benefits; otherwise, the high cost of stylet needles may not be justified.

Although several studies4,5,6,7,8 have reported that stylet needles are cost-effective for thyroid FNA compared to syringe needles, our research yielded contrasting results. Our cost analysis indicated that syringe needle FNA was not only less expensive (500.9 CNY vs. 780 CNY) but also more effective (85.91% adequacy vs. 84.55% adequacy). In previous studies4,5,6,7,8, investigators argued that, despite their higher cost, stylet needles were more cost-effective due to the improved adequacy of stylet needle FNAs, implying a reduced need for repeat FNAs. Conversely, in our study, stylet needles did not demonstrate an advantage in terms of adequacy, and their cost per adequate specimen was higher than that of syringe needles. Given that millions of patients worldwide undergo FNA annually20, adopting cost-effective syringe needles can result in substantial cost savings without compromising efficacy compared to expensive stylet needles.

Our cost analysis does have some limitations, as it only considered direct medical costs and did not account for indirect costs such as lost wages or expenses incurred by patients requiring repeat FNA or diagnostic surgery due to inadequate specimens. However, because the difference in adequacy favored syringe needles over stylet needles, it suggests that stylet needles may result in a higher likelihood of needing repeat FNAs or diagnostic procedures. Thus, including the costs of repeat FNAs, diagnostic procedures, and indirect expenses such as lost labor would likely further widen the cost differential between stylet needles and syringe needles, reinforcing our results. Additionally, our cost analysis was specific to our local context and may not be directly applicable to other settings.

Other limitations were also present in this study. Firstly, the sensitivity and specificity of the two needle FNAs in this study were assessed using postoperative paraffin pathology as the standard reference. However, since benign and indeterminate cases typically do not undergo surgery and thus lack paraffin pathology confirmation, some unoperated nodules may still contain malignancies. Consequently, the true sensitivity is likely somewhat higher, while the specificity may be slightly lower than the values reported. Secondly, the blinding of operators was unfeasible. Thirdly, our study involved five pathologists, and the subjectivity of pathologists could have influenced result determinations. Nevertheless, each patient’s slides were reviewed by the same pathologist. Lastly, needle size for the FNA procedure is a worthy issue29,30, given that 25G needles were exclusively used, our results may not be directly applicable to other needle sizes.

Conclusions

In summary, our findings support the routine use of syringe needles in thyroid FNA. Syringe needle FNA demonstrated non-inferiority to stylet needle FNA in terms of specimen adequacy, and the two needle types exhibited a high degree of concordance in specimen adequacy. Furthermore, syringe needle FNA was both more cost-effective and less expensive. Given the global prevalence of FNA procedures, the economic considerations are paramount, and we recommend the adoption of syringe needles for thyroid FNA.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lee, Y. J. et al. Comparison of cytological adequacy and pain scale score in ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of solid thyroid nodules for liquid-based cytology with with 23- and 25-gauge needles: A single-center prospective study. Sci. Rep. 9, 7027. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43615-7 (2019).

Lee, J. et al. Negative pressure is not necessary for using fine-needle aspiration biopsy to diagnose suspected thyroid nodules: A prospective randomized study. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 96, 216–222. https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2019.96.5.216 (2019).

Dong, Y. et al. Comparison of ultrasound-guided fine-needle cytology quality in thyroid nodules with 22-, 23-, and 25-gauge needles. Anal. Cell Pathol. (Amst). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5544921 (2021).

Cappelli, C. et al. Cost-effectiveness of fine-needle-aspiration cytology of thyroid nodules with intranodular vascular pattern using two different needle types. Endocr. Pathol. 16, 349–354. https://doi.org/10.1385/ep:16:4 (2005).

Cappelli, C. et al. Fine needle cytology of complex thyroid nodules. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 157, 529–532. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-07-0172 (2007).

Cappelli, C. et al. Spinal needle improves diagnostic cytological specimens of thyroid nodules. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 31, 25–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03345562 (2008).

Cappelli, C. et al. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of thyroid nodule: Does the needle matter? South. Med. J. 102, 498–501. https://doi.org/10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31819c7343 (2009).

Cappelli, C. Should we use stylet needles for aspiration cytology of thyroid nodules? Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 5, 84–85. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpendmet1037 (2009).

Tublin, M. E. et al. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration versus fine-needle capillary sampling biopsy of thyroid nodules: Does technique matter? J. Ultrasound Med. 26, 1697–1701. https://doi.org/10.7863/jum.2007.26.12.1697 (2007).

Zhang, Y. F., Li, H., Wang, X. M. & Technical report: A cost-effective, easily available tofu model for training residents in ultrasound-guided fine needle thyroid nodule targeting punctures. Korean J. Radiol. 20, 166–170. https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2017.0772 (2019).

Wang, D. et al. Comparison of fine needle aspiration and non-aspiration cytology for diagnosis of thyroid nodules: A prospective, randomized, and controlled trial. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 66, 67–81. https://doi.org/10.3233/CH-160222 (2017).

Scholten, E. L. et al. Stylet Use does not improve diagnostic outcomes in Endobronchial Ultrasonographic Transbronchial needle aspiration: A randomized clinical trial. Chest 151, 636–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.005 (2017).

Rastogi, A. et al. A prospective, single-blind, randomized, controlled trial of EUS-guided FNA with and without a stylet. Gastrointest. Endosc. 74, 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2011.02.015 (2011).

Wani, S. et al. A comparative study of endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration with and without a stylet. Dig. Dis. Sci. 56, 2409–2414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-011-1608-z (2011).

Wani, S. et al. Diagnostic yield of malignancy during EUS-guided FNA of solid lesions with and without a stylet: A prospective, single blind, randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest. Endosc. 76, 328–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.1395 (2012).

Gimeno-Garcia, A. Z., Paquin, S. C., Gariepy, G., Sosa, A. J. & Sahai, V. Comparison of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology results with and without the stylet in 3364 cases. Dig. Endosc. 25, 303–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01374.x (2013).

Abe, Y. et al. Effect of a stylet on a histological specimen in EUS-guided fine-needle tissue acquisition by using 22-gauge needles: A multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest. Endosc. 82 (e831), 837–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2015.03.1898 (2015).

Xu, Y. et al. Is endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration with a stylet necessary for lymph node screening in lung cancer patients? Braz J. Med. Biol. Res. 50, e6372. https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-431X20176372 (2017).

Sahai, A. V., Paquin, S. C. & Gariepy, G. A prospective comparison of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration results obtained in the same lesion, with and without the needle stylet. Endoscopy 42, 900–903. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1255676 (2010).

Moss, W. J. et al. Needle biopsy of routine thyroid nodules should be performed using a Capillary Action technique with 24- to 27-Gauge needles: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Thyroid 28, 857–863. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2017.0643 (2018).

Luo, P., Mu, X., Ma, W., Jiao, D. & Zhang, P. Effect of a stylet on specimen sampling in thyroid fine needle aspiration: A randomized, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 14, 1062902. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1062902 (2023).

Cibas, E. S. & Ali, S. Z. The 2017 Bethesda System for reporting thyroid cytopathology. Thyroid 27, 1341–1346. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2017.0500 (2017).

Fritscher-Ravens, A. et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in focal pancreatic lesions: A prospective intraindividual comparison of two needle assemblies. Endoscopy 33, 484–490. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2001-14970 (2001).

Welker, L., Akkan, R., Holz, O., Schultz, H. & Magnussen, H. Diagnostic outcome of two different CT-guided fine needle biopsy procedures. Diagn. Pathol. 2, 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-2-31 (2007).

Lee, K. Y. et al. Efficacy of 3 fine-needle biopsy techniques for suspected pancreatic malignancies in the absence of an on-site cytopathologist. Gastrointest. Endosc. 89, 825–831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2018.10.042 (2019).

Lee, J. M. et al. Slow-pull using a fanning technique is more useful than the Standard Suction Technique in EUS-Guided fine needle aspiration in pancreatic masses. Gut Liver 12, 360–366. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl17140 (2018).

Gimeno-Garcia, A. Z., Elwassief, A., Paquin, S. C., Gariepy, G. & Sahai, A. V. Randomized controlled trial comparing stylet-free endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration with 22-G and 25-G needles. Dig. Endosc. 26, 467–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/den.12204 (2014).

Tanaka, A. et al. Optimal needle size for thyroid fine needle aspiration cytology. Endocr. J. 66, 143–147. https://doi.org/10.1507/endocrj.EJ18-0422 (2019).

Sengul, I. & Sengul, D. 29 Apropos of quality for fine-needle aspiration cytology of thyroid nodules with 22-, 23-, 25-, even 27-gauge needles and indeterminate cytology in thyroidology: An aide memory. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. (1992) 68, 987–988. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.20220498 (2022).

Sengul, D. & Sengul, I. Minimum minimorum: Thyroid minimally invasive FNA, less is more concept? Volens nolens? Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. (1992) 68, 275–276. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.20211181 (2022).

Funding

This research was funded by Self-funded Science and Technology Project of Fuyang City (FK202081015) and Fuyang City Health Commission scientific research project (FY2021-014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.L., W.M. and D.J. contributed to the study conception and design. P.L. performed material preparation, data collection and analysis. P.L. wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors approved previous versions of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuyang People’s Hospital (NO: 2022-80). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. This clinical trial has been registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (Registration number ChiCTR2200065318, first registration on 02/11/2022).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, P., Ma, W. & Jiao, D. Thyroid fine needle aspiration specimen adequacy: a noninferiority study and cost-effectiveness comparison of puncture needles. Sci Rep 14, 22554 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74209-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74209-7

This article is cited by

-

Do stylet needles improve diagnostic accuracy in thyroid fine-needle aspiration? A retrospective analysis

BMC Endocrine Disorders (2025)

-

Malignancy prediction for calcified thyroid nodules using deep learning based on ultrasound dynamic videos

Cancer Imaging (2025)