Abstract

This study investigated Vietnamese people’s behavior and future intention to purchase medicines and functional foods online and their associated factors. From March to May 2023, a Google Form questionnaire was distributed via social networks and online platforms. Convenience and snowballing sampling methods were employed to recruit 1,305 Vietnamese people. In the past year, 50.3% of participants purchased at least one kind of medicine and/or functional foods online (medicines: 27.6%, functional foods: 45.1%). Among 656 buyers, nearly a third bought these products more than three times and only 5.9% felt dissatisfied with their previous experiences. This purchasing behavior was more prevalent among females, those married, having higher education levels, usually shopping online, having longer time of Internet use per day, and seeking health information on the Internet (p < 0.001). In addition, 77.5% of participants intended to purchase these products online in the future and 61.2% would introduce this kind of online purchase to other people. The purchase intention was significantly associated with the participants’ previous experiences, area, contracting chronic diseases, and using the Internet for self-medication, while factors associated with the introducing intention included their education level, occupation, and previous experiences in online purchases (p < 0.001).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the rapid development of digital technology and the global Internet boom have given rise to a plethora of advantages for humanity. In the medical field, the roles of the Internet and social media are undisputable, especially in the context of the outbreak of pandemics and epidemics. The Internet has become a popular source for everyone to seek health information1,2. In the pharmaceutical field, the development of the Internet has contributed to providing pharmaceutical services to underserved areas, improving access to medicines, eliminating barriers for people with disabilities or senior citizens, and supporting people during lockdowns because of plagues3. However, the growth of the Internet and social networks also leads to many drawbacks. The ubiquity of electronic gadgets and easy access to the Internet facilitate inappropriate behaviors such as self-diagnosis and self-medication4. People (including children and adolescents) can easily buy medications online. More importantly, people can purchase counterfeit or substandard medicines that can have detrimental effects on their health5. Prescription-only medicines, such as antibiotics, can be bought without prescriptions6,7. Rogue or unapproved online pharmacies were also an intractable problem reported in many previous studies8,9,10. These issues contributed to the complexity of the online market.

Despite the potential risks mentioned above, many people still buy medical products online. Recently, the percentage of people purchasing these products has increased, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic11,12,13,14,15. In many countries, regulatory frameworks specific to online pharmacies and trading medicines on the Internet have yet to be enacted7. No legal documents have been promulgated in Vietnam to guide and manage these activities. In Vietnam, medicines and functional foods are two common types of products sold in pharmacies. As per the Law on Pharmacy, medicines are “preparations that contain active ingredients or herbal ingredients used for the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, alleviation of diseases in humans, and regulation of human physiological functions, including modern drugs, herbal drugs, traditional drugs, vaccines, and biologicals”16. Functional foods are foods used to support the function of parts of the human body, have nutritional effects, make the body comfortable, increase immunization, and reduce the risk of contracting diseases, including supplemented foods, health supplements/dietary supplements/food supplements, food for special medical purposes/medical food, and food for special dietary uses17,18. To distinguish from medicines, the packaging of functional foods must include the words “Functional food” and “This product is not medicine and cannot be replaced with medicine”19.

In the past, Vietnamese people had to go to pharmacies to purchase medicines and functional foods. The Internet and social networks have paved the way for trading these products online in recent years. People could buy medicines and functional foods over the Internet via websites, social networks, and mobile applications. The Ministry of Health and relevant organizations have endeavored to curb illegal activities involving the online trade of medicines20. However, this type of trade still blatantly happens. Many sellers have taken advantage of customers’ lack of knowledge, loopholes in laws, and the uncontrollability of the online market to trade these products on the Internet. Approximately 79.1% of Vietnamese people (78.44 million citizens) use the Internet21. This vast number of Internet users can become potential online buyers. However, no studies have been conducted to assess Vietnamese people’s online purchase of medicines and functional foods. This study was carried out to investigate Vietnamese people’s behavior and future intention to purchase medicines and functional foods online and their associated factors.

Methods

Study setting, sampling method, and data collection

The following formula was employed to estimate the minimum sample size for a proportion: n = Zα/22.p.(1-p)/d2. With α = 0.01, Zα/2=2.575, p = 0.5 (to attain the maximum of p.(1-p)22), d = 0.05, the minimum sample size was 663 people. The research team endeavored to approach as many Vietnamese people as possible to increase the reliability, generalization, and extrapolation of results. The questionnaire was designed as a Google Form link and distributed to participants via social networks and online platforms (including Facebook, Messenger, and Zalo, a chatting app popularly used by Vietnamese people). The research team used convenience and snowballing sampling methods to recruit participants from March to May 2023. Eligible participants must be Vietnamese people, be able to understand Vietnamese, be at least 18 years old, and use the Internet.

The questionnaire and variables

The research team developed a questionnaire after reviewing documents and referencing previous scientific articles12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Regarding face validity, a government official from the Vietnam Ministry of Health and two lecturers/researchers from the Phenikaa University and Hanoi University of Pharmacy reviewed the initial questionnaire. After that, a pilot study with the participation of 30 Vietnamese people was conducted to assess the clarity and intelligibility of each question and compute the questionnaire’s internal consistency. Two weeks later, these 30 participants answered this questionnaire one more time. Their responses between the two measurements were compared to evaluate the questionnaire’s test-retest reliability. The data of these people were not used in the final analysis. The final questionnaire (Vietnamese language) embraced four main parts: (1) participants’ characteristics, (2) Internet use, (3) knowledge/attitudes towards purchasing medicines/functional foods online, and (4) their purchase behavior and future intention. The definitions of medicines and functional foods (in the Introduction above) were also mentioned in the questionnaire to guarantee that participants could comprehend all questions.

Primary outcomes/dependent variables

Regarding purchase behavior (eleven questions in total), three main questions included: (1) “Have you ever purchased medicines online in the past year?”, (2) “Have you ever purchased functional foods online in the past year?”, and (3) “Have you ever bought medicines and/or functional foods online from foreign sources (such as international websites)?”. A person was classified as “purchased medicines and/or functional foods” if this person answered “Yes” to either of the first two questions. Online buyers were also asked about (4) their level of satisfaction, (5) reasons for their satisfied or dissatisfied experience, (6) names of products purchased online, (7) the number of times they purchased medicines/functional foods online in the past year, (8) several activities when they purchased products online, (9) points of purchase, (10) how they knew the online purchase of medicines/functional foods, and (11) their criteria to choose the points of online purchase.

About future intention, three yes/no questions included: (1) “In the future, will you purchase medicines on the Internet?”, (2) “In the future, will you purchase functional foods on the Internet?”, and (3) “Do you intend to introduce the online purchase of these products to other people (such as friends and family members)?”. A person was classified as “having the intention to purchase medicines and/or functional foods in the future” if this person answered “Yes” to either of the first two questions.

Independent variables

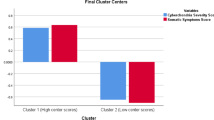

Participants’ knowledge and attitudes towards purchasing medicines and functional foods online were measured via 31 items (knowledge: 8 items and attitudes: 23 items). The items and scoring can be seen in Table S1. Participants’ scores could range from 0 to 16 (knowledge) and 23 to 115 (attitudes). The good reliability of this questionnaire was demonstrated via Cronbach’s alpha (knowledge: 0.85, attitudes: 0.95), Omega Total (0.96), and Spearman-Brown split-half reliability (knowledge: 0.82, attitudes: 0.94). In addition, its good test-retest reliability between two different times of measurements was displayed with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) higher than 0.75 (knowledge: 0.80 (95% confidence interval (95%CI): 0.67–0.89), attitudes: 0.93 (95%CI: 0.90–0.96)).

Questions regarding participants’ Internet usage included (1) their frequency of Internet use (rarely, sometimes, usually), (2) average time of Internet use per day (hours), (3) frequency of online shopping for any products or services (never, rarely, sometimes, usually), (4) using the Internet to seek health information (yes/no), (5) self-diagnosis without visiting a doctor based on health information from the Internet (yes/no), and (6) self-medication without consulting a pharmacist or doctor based on health information from the Internet (yes/no). In addition, ten questions about participants’ general characteristics encompassed (1) year of birth, (2) sex, (3) residence/region (north, central, south), (4) area (urban, rural), (5) highest level of education, (6) marital status, (7) working status/occupation, (8) average monthly income, allowance, or retirement pension, (9) having a health insurance card, and (10) contracting chronic diseases.

Data analysis

R software version 4.3.3 was used to analyze the data using the following packages: psych, irr, ggplot2, gridExtra, BAS, ResourceSelection, Epi, and pROC. Numeric variables (such as age) were described via mean and standard deviations (SD), while exact numbers and percentages were used to report categorical variables (such as sex). Factors associated with Vietnamese people’s behavior and intention to purchase medicines and functional foods online were identified via univariate and multivariate logistic regression models. To minimize the models’ complexity and avoid multicollinearity/overfitting, the Bayesian Model Averaging method was employed to select independent variables in multivariate models. Furthermore, Hosmer–Lemeshow tests and the area under the curve (AUC) were computed to assess the goodness of fit of these models. A p-value < 0.001 was considered statistical significance.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Hanoi University of Pharmacy (No: 193/QĐ-DHN) and the ethics committee of the Nam Dinh University of Nursing (No: 460/GCN-HĐĐĐ). Online informed consent was obtained from all 1,305 participants who chose a “Yes” answer to the question, “Do you agree to participate in this research?”. This survey stopped when a person chose a “No” answer. All study procedures and methods were performed in accordance with the relevant regulations and guidelines.

Results

General characteristics of participants

Among 1,317 Vietnamese people approached, 1,305 people agreed to participate in this research (99.1%). Most participants (n = 1,217, 93.3%) were under 50 years old (average: 29.91 ± 11.36 years old). A third were males (n = 451, 34.6%). Two-fifths got married (n = 514, 39.4%). More than half lived in the north (n = 737, 56.5%). Four-fifths came from urban areas (n = 1,046, 80.2%). Nearly a third have an education level of university or higher (n = 410, 31.4%). The number of participants working in healthcare was 82 people (6.3%). The average monthly income, allowance, and/or retirement pension of about three-quarters (n = 977, 74.9%) were lower than twelve million Vietnam dongs (590.328US$). Almost all participants possessed at least one health insurance card (n = 1,275, 97.7%). About a sixth (n = 234, 17.9%) came down with at least one chronic disease (for example, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and sinusitis) (Table 1).

Regarding Internet usage, the frequency of using the Internet among all participants was high (usually: n = 945, 72.4%), while that of online shopping for any products/services was relatively low (usually: n = 153, 11.7%). On average, a participant spent roughly 6.26 ± 3.59 h per day using the Internet. The Internet was a common source for almost all participants to seek health information (n = 1,273, 97.5%), including self-diagnosis (n = 839, 64.3%) and self-medication (n = 953, 73.0%). In addition, the average knowledge score of all participants regarding purchasing medicines/functional foods online was 6.21 ± 2.79 (range: 0–16). Their average attitude score was 87.46 ± 16.05 (range: 23–115) (Table 1).

Purchasing medicines and functional foods online in the past year

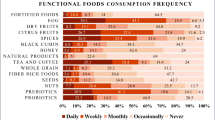

In the past year, half of the participants (n = 656, 50.3%) purchased at least one kind of medicine and/or functional foods on the Internet (medicines: n = 360, 27.6%, functional foods: n = 588, 45.1%). One-seventh (n = 190, 14.6%) bought these products from foreign sources, such as international websites (Fig. 1). Among 656 buyers, nearly a third bought these products more than three times in the past year (n = 209, 31.9%). Participants’ points of purchase encompassed online pharmacies (n = 317, 48.3%), social networks (n = 309, 47.1%), and manufacturers’ websites (n = 262, 39.9%). Their sources of information included the Internet, social networks, mobile applications (n = 450, 68.6%), and their family/friends (n = 267, 40.7%). Several criteria for choosing the points to purchase medicines/functional foods online included the reviews/comments of previous buyers (n = 439, 66.9%), the clarity and reliability of products and manufacturers (n = 430, 65.5%), and the qualification and reliability of the sellers/suppliers (n = 426, 64.9%) In addition, 267 individuals felt satisfied with their previous experience in purchasing these products online (40.7%). The number of dissatisfied customers was 39 people (5.9%). (Table 2).

As per the multivariate logistic regression models, factors associated with this purchase behavior of Vietnamese people included sex, marital status, education level, average time of Internet use per day, frequency of online shopping, and using the Internet to seek health information for self-diagnosis and self-medication (p < 0.001). The prevalence of purchasing medicines/functional foods online was lower among males (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 0.61, 95%CI: 0.47–0.80) and the unmarried (aOR = 0.41, 95%CI: 0.26–0.66). By contrast, this purchase behavior was more prevalent among individuals with an education level of university or higher (aOR = 2.27, 95%CI: 1.62–3.18), sometimes/usually shopping online (sometimes: aOR = 2.03, 95%CI: 1.54–2.66; usually: aOR = 3.24, 95%CI: 2.12–4.95), longer time of Internet use per day (one-hour increase: aOR = 1.08, 95%CI: 1.04–1.12), using the Internet for self-diagnosis (aOR = 1.91, 95%CI: 1.44–2.54) and self-medication (aOR = 1.79, 95%CI: 1.30–2.47) (Table 3). Univariate analyses were reported in Table S2.

Intention to purchase medicines and functional foods online in the future

More than three-quarters of the participants (n = 1,011, 77.5%) had the intention of purchasing medicines/functional foods online in the future (medicines: n = 724, 55.5%; functional foods: n = 980, 75.1%) (Fig. 1). Their purchase intention was associated with previous experiences in online purchases, area, contracting chronic diseases, and using the Internet for self-medication (p < 0.001). In particular, future purchase intention was more prevalent among people purchasing medicines/functional foods online in the past year (aOR = 13.48, 95%CI: 7.86–23.13), living in urban areas (aOR = 2.23, 95%CI: 1.56–3.17), and self-medicating via health information sought from the Internet (aOR = 1.93, 95%CI: 1.35–2.74). However, the likelihood of purchasing these products online in the future sharply diminished among those who experienced dissatisfaction with previous online purchases (aOR = 0.08, 95%CI: 0.03–0.18) and those having at least one chronic disease (aOR = 0.49, 95%CI: 0.33–0.73) (Table 4).

About 61.2% of participants (n = 799) intended to introduce the online purchase of these products to other people (Fig. 1). This future intention was significantly associated with their education level, occupation, and previous experiences in online purchases (p < 0.001). The intention to introduce the online purchase of medicines/functional foods to other people was more prevalent among participants having an education level of university or higher (aOR = 1.96, 95%CI: 1.42–2.69) and those not working in the medical field/being students (aOR = 2.69, 95%CI: 1.55–4.69). Furthermore, this intention was significantly associated with the online purchasing behavior in the past year (aOR = 2.89, 95%CI: 1.85–4.50) and times of purchasing medicines/functional foods online in the past year (one-purchase increase: aOR = 1.32, 95%CI: 1.15–1.52). By contrast, this intention considerably decreased among purchasers dissatisfied with previous online buying (aOR = 0.13, 95%CI: 0.06–0.27) (Table 4). Univariate analyses were reported in Table S3.

Discussion

The development of cutting-edge technology and the omnipresence of electronic gadgets connected to the Internet have facilitated the outstanding growth of online trading in recent years. Numerous people have a predilection for online shopping because of its benefits, such as convenience and time-saving. During the COVID-19 pandemic, online trading and doorstep delivery played a crucial role in hindering the transmission of this virus and protecting people’s health. In this study, half of the participants purchased medicines and/or functional foods online in the past year. The common points of purchase included online pharmacies, social networks, and manufacturers’ websites. Factors associated with their purchase behavior included sex, marital status, education level, average time of Internet use per day, frequency of online shopping, and using the Internet to seek health information for self-diagnosis and self-medication. More than three-quarters of the participants intended to purchase these products online in the future. Factors significantly associated with this intention included their previous experiences in online purchases, area, contracting chronic diseases, and using the Internet for self-medication. Besides, three-fifths of the participants intended to introduce this buying to other people. This intention was significantly associated with their education level, occupation, and previous experiences in online purchases.

The percentage of people purchasing health products online varied among countries and years of study. A multinational web-based survey in 22 countries showed that the percentages of the participants buying medicinal products, herbal products, and supplementary/nutritional products via the Internet were 11.9%, 18.8%, and 28.8%, respectively28. About 14.5% of Internet users in the United States purchased a medication or vitamin online11. In Jordan, roughly 11.8% of people purchased medicines over the Internet in the past32. In this study, 50.3% of Vietnamese people purchased at least one kind of medicine and/or functional foods online (medicines: 27.6%, functional foods: 45.1%). This high percentage may spring from the time of study. People were asked about whether or not they purchased medicines/functional foods online in the past year. During this period, several outbreaks of the COVID-19 pandemic occurred in Vietnam. People were recommended not to go outside their houses. During several specific intervals, lockdowns, social distance, and self-isolation were also applied, and this pandemic became the rationale behind the online purchase of these products among many citizens. Our results were in line with the findings of several previous studies. In 2020–2023, the percentages of people in four countries (including the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, and Slovakia) buying medicines and other health products over the Internet were 55.5% and 63.0%, respectively29. In Saudi Arabia, 60.2% of people purchased products from online pharmacies in the past (within the past three months (the year 2022): 53.4%)33.

Sex, marital status, education level, average time of Internet use per day, frequency of online shopping, and using the Internet to seek health information were factors significantly associated with the purchase behaviors of Vietnamese people regarding medicines/functional foods on the Internet. This behavior among Vietnamese females was more popular than among males, similar to a study in Russia34. Another previous study even showed that the female gender was one of seven predictors of online shopping addiction35. A previous study showed that married people spent significantly less time on leisure activities than single individuals36. Online shopping can be a valuable method to save time for the former. Vietnamese people with high education levels were more likely to purchase these products online, aligning with the results of two studies in the United Arab Emirates and Romania12,14. Besides, the more time a person spends accessing the Internet and searching for health information, the more likely they are to reach links, websites, or online pharmacies selling medicines/functional foods. This can be a potential rationale behind the high likelihood of purchasing these products online among individuals usually shopping online, having longer time of Internet use per day, and seeking health information on the Internet for self-diagnosis and self-medication.

This study also witnessed a high proportion of Vietnamese people intending to purchase medicines/functional foods online in the future and introduce this buying to other people. Their intentions were significantly associated with previous experiences in buying these products online. Notably, the percentage of Vietnamese people dissatisfied with their previous online purchases was low, in line with a study in Saudi Arabia33. In addition, individuals purchasing medicines/functional foods online in the past year were 13.48 times more likely to continue buying these merchandise online in the future compared to the non-buyer group. These can facilitate the development of activities involving trading medicines and functional foods online. Several other factors also associated with Vietnamese people’s intention to purchase these products online included the frequency of Internet use/time of Internet use, the frequency of online shopping, and using the Internet to seek health information, in line with the results of a study in Hungary when individuals using the Internet more and buying goods online would be more likely to purchase medications online24.

There is a high potential for future uptake of the online medicines/functional foods trade. A myriad of people, not only in Vietnam but also in many other countries, intend to purchase these products online in the future23,31,37. Several rationales behind the great need for this online buying include convenience38, privacy39, low prices25, low availability of essential medicines in local pharmacies26,40,41, a wide variety of products, and easy online access15,33. Therefore, the number of people supporting the legalization of online medical product trade is on the increase30,42,43. The rapid proliferation of online trade, the anonymity, and the inability to enforce against overseas sellers have challenged the government and authorities to manage and control the online trading of these products44. Online sellers can take advantage of the lack of knowledge and perception to defraud consumers45. On the Internet, illegal medicine sellers usually do not require prescriptions, do not show their contact details, do not limit the number of purchasable products, do not offer pharmacists’ consultations, and even trade counterfeit and substandard medicines9,10,46. Up to 2023, trading medicines online is illegal in Vietnam, and no specific laws/documents relevant to the online trade of these products have been promulgated. However, the Vietnam Ministry of Health, policymakers, and relevant authorities are going to promulgate legal documents and laws related to online pharmacies and trading medicines on the Internet in the forthcoming years. Then, enhancing people’s knowledge about the online purchase of these products and how to choose legitimate points of purchase is of paramount importance as it is impossible to curb the online trading of these products.

This is the first study conducted to investigate Vietnamese people’s behavior and future intention to purchase medicines/functional foods online. Having a large sample size, employing the Bayesian Model Averaging method to select variables in the multivariate models, and the high values of AUC are other strengths. However, this study also has several following limitations. First, this is only a cross-sectional study. Therefore, the causal relationship between people’s behavior and intention to purchase medicines/functional foods online and independent factors cannot be determined. The participants cannot be representative of the Vietnamese population as they were recruited using convenience and snowballing sampling methods. In addition, using an online survey and a self-report questionnaire to collect data may lead to several biases (such as recall bias).

Conclusions

In the past year, half of the participants purchased medicines/functional foods on the Internet. Factors associated with their purchase behavior included sex, marital status, education level, average time of Internet use per day, frequency of online shopping, and using the Internet to seek health information for self-diagnosis and self-medication. Numerous people intend to purchase these products online in the future and will introduce this online purchase to other people. The former was significantly associated with their previous experiences in online purchases, area, contracting chronic diseases, and using the Internet for self-medication, while education level, occupation, and previous experiences were associated with the latter.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 95%CI:

-

95% Confidence Interval

- aOR:

-

adjusted odds ratio

- AUC:

-

area under the curve

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- ICC:

-

intraclass correlation coefficient

- US:

-

the United States

References

Zhang, D. et al. Online health information-seeking behaviors and skills of Chinese college students. BMC Public. Health. 21 (1), 736. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10801-0 (2021).

Aldebasi, B., Alhassan, A. I., Al-Nasser, S. & Abolfotouh, M. A. Level of awareness of Saudi medical students of the internet-based health-related information seeking and developing to support health services. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 20 (1), 209. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-020-01233-8 (2020).

Jirjees, F. et al. The rise of telepharmacy services during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive assessment of services in the United Arab Emirates. Pharm. Pract. (Granada). 20 (2), 2634. https://doi.org/10.18549/PharmPract.2022.2.2634 (2022).

Iftikhar, R. & Abaalkhail, B. Health-seeking influence reflected by Online Health-related messages received on Social Media: cross-sectional survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 19(11), e382. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5989 (2017).

Miller, R. et al. When technology precedes regulation: the challenges and opportunities of e-pharmacy in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health 6(5), e005405. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005405 (2021).

Gong, Y. et al. Over-the-counter antibiotic sales in community and online pharmacies, China. Bull. World Health Organ. 98(7), 449–457. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.19.242370 (2020).

Mackey, T. K. et al. Multifactor Quality and Safety Analysis of Antimicrobial drugs sold by online pharmacies that do not require a prescription: Multiphase Observational, Content Analysis, and product evaluation study. JMIR Public. Health Surveill. 8 (12), e41834. https://doi.org/10.2196/41834 (2022).

Ozawa, S., Billings, J., Sun, Y., Yu, S. & Penley, B. COVID-19 treatments sold online without prescription requirements in the United States: cross-sectional study evaluating availability, Safety and Marketing of medications. J. Med. Internet Res. 24 (2), e27704. https://doi.org/10.2196/27704 (2022).

Monteith, S., Glenn, T., Bauer, R., Conell, J. & Bauer, M. Availability of prescription drugs for bipolar disorder at online pharmacies. J. Affect. Disord. 193, 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.043 (2016).

Monteith, S. & Glenn, T. Searching online to buy commonly prescribed psychiatric drugs. Psychiatry Res. 260, 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.037 (2018).

Desai, K., Chewning, B. & Mott, D. Health care use amongst online buyers of medications and vitamins. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 11 (6), 844–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.01.001 (2015).

Pal, S. et al. Attitude of patients and customers regarding Purchasing drugs Online. Farmacia. 63 (1), 93–98 (2015).

Fittler, A., Lankó, E., Brachmann, B. & Botz, L. Behaviour analysis of patients who purchase medicines on the internet: can hospital pharmacists facilitate online medication safety? Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 20, 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/ejhpharm-2012-000085 (2013).

Jairoun, A. A. et al. Online medication purchasing during the Covid-19 pandemic: potential risks to patient safety and the urgent need to develop more rigorous controls for purchasing online medications, a pilot study from the United Arab Emirates. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 14(1), 38. Erratum in: J Pharm Policy Pract. 2021;14(1):44. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-021-00320-z

Alwhaibi, M. et al. Evaluating the frequency, consumers’ motivation and perception of online medicinal, herbal, and health products purchase safety in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 29 (2), 166–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2020.12.017 (2021).

The Vietnam National Assembly. Law on Pharmacy, No. 105/2016/QH13. https://vbpl.vn/TW/Pages/vbpqen-toanvan.aspx?ItemID=11099 (2016) [last accessed 18 Aug 2024].

The Vietnam National Assembly. Law on Food Safety. No. 55/2010/QH 12. https://vanban.chinhphu.vn/default.aspx?pageid=27160&docid=96032 (2010) [last accessed 18 Aug 2024].

The Vietnam Ministry of Health. Circular regulating the management of functional foods. No. 43/2014/TT-BYT. https://vanban.chinhphu.vn/default.aspx?pageid=27160&docid=178185 (2014) [last accessed 18 Aug 2024].

The Vietnam Government. Decree on Good Labels. No. 43/2017/ND-CP. https://vanban.chinhphu.vn/default.aspx?pageid=27160&docid=189385 (2017) [last accessed 18 Aug 2024].

TuoiTre Online. Ho Chi Minh City Department of Health: Selling drugs via social networks is a violation that will be corrected and handled. URL: (2022). https://tuoitre.vn/so-y-te-tp-hcm-ban-thuoc-qua-mang-xa-hoi-la-vi-pham-se-chan-chinh-xu-ly-20220519181204089.htm [last accessed 18 Aug 2024].

Kemp, S. D. : Vietnam. 2024. URL: (2024). https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-vietnam#:~:text=There%20were%2078.44%20million%20internet%20users%20in%20Vietnam%20in%20January%202024 [last accessed 18 Aug 2024].

Thompson, S. K. Sampling. 3rd Edition (Wiley, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118162934

Abanmy, N. The extent of use of online pharmacies in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 25 (6), 891–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2017.02.001 (2017).

Fittler, A., Vida, R. G., Káplár, M. & Botz, L. Consumers turning to the internet pharmacy Market: cross-sectional study on the frequency and attitudes of Hungarian patients Purchasing medications Online. J. Med. Internet Res. 20 (8), e11115. https://doi.org/10.2196/11115 (2018).

Bowman, C., Family, H., Agius-Muscat, H., Cordina, M. & Sutton, J. Consumer internet purchasing of medicines using a population sample: a mixed methodology approach. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 16 (6), 819–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.09.056 (2020).

Bansal, S. et al. A preliminary study to evaluate the behavior of Indian population toward E-pharmacy. Indian J. Pharmacol. 54 (2), 131–137. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijp.ijp_836_21 (2022).

Almomani, H., Patel, N. & Donyai, P. News Media Coverage of the Problem of Purchasing fake prescription Medicines on the internet: thematic analysis. JMIR Form. Res. 7, e45147. https://doi.org/10.2196/45147 (2023).

Assi, S., Thomas, J., Haffar, M. & Osselton, D. Exploring consumer and patient knowledge, Behavior, and attitude toward Medicinal and Lifestyle products purchased from the internet: a web-based survey. JMIR Public. Health Surveill. 2 (2), e34. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.5390 (2016).

Fittler, A. et al. Attitudes and behaviors regarding online pharmacies in the aftermath of COVID-19 pandemic: at the tipping point towards the new normal. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 1070473. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1070473 (2022).

Lobuteva, L., Lobuteva, A., Zakharova, O., Kartashova, O. & Kocheva, N. The modern Russian pharmaceutical market: consumer attitudes towards distance retailing of medicines. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22 (1), 582. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07991-7 (2022).

Ndem, E., Udoh, A., Awofisayo, O. & Bafor, E. Consumer and community pharmacists’ perceptions of online pharmacy services in Uyo Metropolis, Nigeria. Innov. Pharm. 10 (3). https://doi.org/10.24926/iip.v10i3.1774 (2019).

Gharaibeh, L. et al. Practices, perceptions and trust of the public regarding online drug purchasing: a web-based survey from Jordan. BMJ Open. 13 (10), e077555. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-077555 (2023).

Almohammed, O. A. et al. Public awareness of online pharmacies, consumers’ motivating factors, experience and satisfaction with online pharmacy services, and current barriers and motivators for non-consumers: the case of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 31 (8), 101676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.06.009 (2023).

Soboleva, M. S., Loskutova, E. E. & Kosova, I. V. Problems of purchasing pharmacy products through online orders. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 13 (4), 286–290. https://doi.org/10.4103/japtr.japtr_454_22 (2022).

Rose, S. & Dhandayudham, A. Towards an understanding of internet-based problem shopping behaviour: the concept of online shopping addiction and its proposed predictors. J. Behav. Addict. 3 (2), 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1556/JBA.3.2014.003 (2014).

Lee, Y. G. & Bhargava, V. Leisure time: do married and single individuals spend it differently? Family Consumer Sci. Res. J. 32 (3), 254–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077727X03261631 (2004).

Abu-Farha, R. et al. Perception and willingness to Use Telepharmacy among the General Population in Jordan. Patient Prefer Adherence. 17, 2131–2140. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S428470 (2023).

Ang, J. Y., Ooi, G. S., Abd Aziz, F. & Tong, S. F. Risk-taking in consumers’ online purchases of health supplements and natural products: a grounded theory approach. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 16 (1), 134. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-023-00645-x (2023).

Mackey, T. K. & Nayyar, G. Digital danger: a review of the global public health, patient safety and cybersecurity threats posed by illicit online pharmacies. Br. Med. Bull. 118 (1), 110–126. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldw016 (2016).

Nguyen, H. T. T., Dinh, D. X., Nguyen, T. D. & Nguyen, V. M. Availability, prices and affordability of essential medicines: a cross-sectional survey in Hanam province, Vietnam. PLoS One. 16 (11), e0260142. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260142 (2021).

Dinh, D. X., Nguyen, H. T. T. & Nguyen, V. M. Access to essential medicines for children: a cross-sectional survey measuring medicine prices, availability and affordability in Hanam province, Vietnam. BMJ Open. 11 (8), e051465. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051465 (2021).

Alfian, S. D. et al. Knowledge, perception, and willingness to provide telepharmacy services among pharmacy students: a multicenter cross-sectional study in Indonesia. BMC Med. Educ. 23 (1), 800. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04790-4 (2023).

Siddiqua, A. et al. Community pharmacists’ knowledge and perception towards Telepharmacy Services and willingness to practice it in light of COVID-19. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2024, 6656097. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/6656097 (2024).

Sng, Y. J. et al. The problems with Online Health product sales: how can regulations be improved? Drug Saf. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-024-01414-8 (2024).

Jillani, Z., Reinhard, L. & Hertig, J. A narrative review of illegal online pharmacies and contemporary issues with restricting FDA-approved medication access. J. Med. Access. 7, 27550834231220512. https://doi.org/10.1177/27550834231220512 (2023).

Ho, H. M. K., Xiong, Z., Wong, H. Y. & Buanz, A. The era of fake medicines: investigating counterfeit medicinal products for erectile dysfunction disguised as herbal supplements. Int. J. Pharm. 617, 121592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2022.121592 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors want to express their deep gratitude to all 1,305 individuals who voluntarily and enthusiastically participated in our research.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DDA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing. NHV: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – Review & Editing. PLN: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing. DXD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Validation, Roles/Writing - original draft, Writing – Review & Editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Doan, D.A., Vu, N.H., Nguyen, P.L. et al. Vietnamese people’s behavior and future intention to purchase medicines and functional foods on the internet: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 14, 24267 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75029-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75029-5