Abstract

Pregnancy complications can’t always be predicted. However, pregnant women must be aware of these pregnancy complications to avoid serious complications and begin treatment as soon as possible. Maternal mortality can be decreased by offering high-quality maternity services and educating women about the early warning signs of pregnancy. Therefore, the current study aimed to assess individual and community-level factors associated with women’s knowledge about pregnancy complications in Ethiopia based on the 2019 Ethiopian mini-demographic health survey data (EMDHS). The study analyzed data from the 2019 EMDHS, including a weighted sample of 1,655 reproductive-age women. Multilevel binary logistic regression analysis was used to fit the associated variables. Using the interclass correlation (ICC), deviance, proportional change variance (PVC), and median odds ratio (MOR), the comparison and fit of the models were evaluated. The significant variables associated with knowledge about complications during pregnancy were identified using an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) and a 95% confidence interval (CI). The proportion of mothers with good knowledge of pregnancy complications was 44.8% (CI 42.4%–47.2%). The multi-level analysis revealed that secondary education (AOR = 1.54, 95% CI = 1.04–2.29), a higher education level (AOR = 1.74, 95% CI = 1.11–2.72), four and above ANC Visits (AOR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.49–0.98), women who lived in Amhara (AOR = 2.10, 95% CI = 1.24–3.55), and SNNPR (AOR = 3.92, 95% CI = 2.10–7.31) were positively associated with knowledge about pregnancy complications while, women residing in Harari (AOR = 0.20, 95% CI = 0.98–0.44) and Dire-Dawa (AOR = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.24–0.95) were negatively associated with knowledge about pregnancy complications. This study found that nearly half (44.8%) of the study participants demonstrated knowledge about pregnancy complications. This suggests a significant gap in awareness that could potentially impact access to obstetric care for women experiencing complications during pregnancy. Therefore, prioritizing enhancements in antenatal counseling services and community health education regarding pregnancy complications is crucial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2020, there were over 800 preventable pregnancy and childbirth-related deaths every day, or about one death every two minutes1. In 2020, 287,000 women lost their lives both during and after pregnancy and childbirth worldwide. Low and middle-income countries accounted for about 95% of all maternal deaths, the majority of which were preventable2. Of the anticipated 253,000 maternal fatalities worldwide in 2020, 87% occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia. Approximately 70% of maternal deaths (202, 000) occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa2,3 Yet maternal deaths only provide a portion of the picture. Twenty to thirty additional women will experience both short- and long-term problems, such as obstetric fistula, infections, a ruptured uterus, or pelvic inflammatory disease, for every woman who dies from pregnancy-related reasons4.

Ethiopia’s alarmingly high maternal mortality rate (MMR) persists despite all efforts and actions. The Demographic Health Survey of 2016 (DHS-2016) indicates that Ethiopia has an MMR of 412 per 100,000 live births5. In addition, every year over 500,000 Ethiopian women and girls experience disability as a result of complications during pregnancy and childbirth. Pregnancy problems, such as hemorrhage (29.9%), obstructed labor/ruptured uterus (22.3%), pregnancy-induced hypertension (16.9%), puerperal infection (14.68%), and unsafe abortion (8.6%), are the leading causes of maternal death in Ethiopia1,4.

Knowledge of pregnancy, labor, and delivery complications is crucial for safe motherhood6. Pregnancy danger signs are symptoms that should raise red flags for a pregnant woman and her fetus and necessitate prompt medical intervention7. The most typical warning signs of pregnancy include swollen hands and/or face, blurred vision, and heavy vaginal bleeding: Severe vaginal bleeding, protracted labor, and convulsions are dangerous indicators during labor and delivery; severe bleeding after delivery, unconsciousness after delivery, and fever are danger signs during the postpartum period8. Numerous problems that cause maternal deaths and contribute to prenatal deaths can have abrupt and severe onsets, and they are often unforeseen9. One of the most frequent reasons people fail to recognize a problem when it occurs and delay health care-seeking behavior is poor knowledge of pregnancy complications9,10. Ethiopia’s national reproductive plan places a strong focus on maternal and newborn health to lower the high rates of maternal and neonatal deaths10.

Achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, particularly target 16, requires extensive ongoing efforts11. The Ethiopian Government has initiated several reforms, such as launching the Community Based Health Insurance (CBHI) program in 201012, to enhance healthcare financing and meet SDG targets, particularly in reducing maternal mortality and improving access to primary healthcare13. Although maternal mortality rates in Ethiopia decreased between 2000 and 2016, they remain alarmingly high1,3. Our study data can assess whether maternal awareness of pregnancy-related issues has improved since the last Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS).

The prevalence of knowledge regarding pregnancy complications varies across different locations: 26.3% in Chiro town14, 74.4% in Debre Tabor Town15, 63.2% in Hosanna Town16, and 21.9% in Gedeo zone17. According to different literature, knowledge of pregnancy complications was significantly associated with age15,16,18, religion15 educational status16,19,20, occupation18,20, parity16,18, parity21, place of delivery9, and frequency of ANC visits15,16,18. Despite the availability of localized studies in Ethiopia, there remains a scarcity of nationally summarized data on women’s knowledge about pregnancy complications. Furthermore, these studies often do not assess the influence of factors such as mode of delivery, type of birth, birth spacing, regional variation, and household head on women’s knowledge of pregnancy complications. Therefore, the current study aimed to assess individual and community-level factors associated with women’s knowledge about pregnancy complications in Ethiopia based on the 2019 MEDHS data.

Methods

Study design, setting, and period

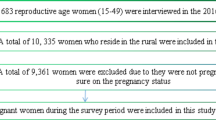

Cross-sectional data from the EMDHS 2019 were used in this study. The EMDHS is a five-year nationally representative survey. Since 2000, Ethiopia has carried out four EDHSs every five years. The country is divided into nine regions and two city administrations. Contextually, these regions are categorized as agrarian (Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People Region (SNNPR), Amhara, Benishangul-Gumuz, Gambela, Harari, Oromia, Tigray); pastoralist (Afar, and Somali); city administrations (Addis Abe and Dire-Dawa)22,23,24,25. We obtained the data for this study from the DHS website (www.dhsprogram.com) after requesting authorization online and providing justification for the investigation. From the woman record (IR file), we extracted the independent and dependent variables. EDHS is a nationally representative household survey that is carried out on a broad spectrum of demographics through face-to-face interviews. The Central Statistical Agency generated a sampling frame of all census enumeration areas for the 2019 Ethiopia Population and Housing Census (PHC), which was used by EMDHS 2019. An Enumeration Area (EA) is a geographic area covering an average of 131 households. A comprehensive list of 149,093 Enumeration areas was produced for the 2019 PHC. Enumeration areas were sampled separately in each of the 21 strata resulted from stratifying the nine regions and two city administrations into rural and urban categories. Before choosing the sample, a probability proportionate allocation was done based on the size of the Enumeration area. Prior to conducting the analysis, we verified the inclusion of the outcome variable in the EMDHS dataset and assessed all study variables for missing data. Cases with missing observations were omitted from the analysis. Furthermore, the dataset was weighted to correct for sample non-representativeness across regions in Ethiopia, thereby ensuring accurate estimates and standard errors. The study analyzed a weighted sample comprising 1,655women who gave birth in the last 12 months. The detailed sampling procedure is presented in a full EMDHS 2019 report26.

Study variables

Dependent variable

The outcome variable of this study is maternal knowledge about pregnancy complications.

Independent variables

Independent variables were classified into individual and community-level factors. Individual level factors were religion, maternal age, maternal education, head of household, wealth index, marital status, mode of delivery, type of birth, frequency of ANC visit, and sex of the child. Community-level factors were residence and administrative region.

Measurement of variables

The 2019 EMDHS data had eight dichotomized questionnaires that addressed maternal knowledge about pregnancy complications. The eight pregnancy complication questionnaires are S415A, S415B, S415C, S415D, S415E, S415F, S415G, and S415X. These eight questionnaires were used to collect data from mothers using No (0) and Yes (1) options.

Definition

Pregnancy complications

Pregnancy complications include vaginal bleeding, vaginal gush of fluid, severe headache, blurred vision, fever, abdominal pain, convulsion, and others27.

Knowledge about pregnancy complications

Assessment of what mothers described about pregnancy complications using the aforementioned eight questions.

Knowledge about pregnancy complications

A comprehensive assessment of participants’ knowledge regarding pregnancy complications was conducted using a set of eight items. Correct responses were assigned a value of 1, while incorrect responses were assigned a value of 0. The resulting scoring scale ranged from 0 to 8 points. Subsequently, participants’ level of knowledge was dichotomously categorized as either “good knowledge” (those surpassing the mean score) or “poor knowledge” (those falling below the mean score), based on the cumulative mean score of participants’ knowledge of pregnancy complications16,28.

Data management and statistical analysis

We weighted the data to account for the non-proportional distribution of samples among strata and regions before doing the descriptive data analysis. Next, using weighted frequencies, mean ± (standard deviations), and percentage, descriptive statistics were calculated and presented. STATA version 17 (STATA Corporation, IC., TX, USA) was used for all analyses.

Multilevel logistic regression was employed due to the hierarchical and nested nature of the EDHS data. To determine the random effect, intra-community correlation (ICC) was used, computed as, \(ICC = \frac{{\delta {\text{a}}^{2} }}{{\delta {\text{a}}^{2} + \delta {\text{b}}^{2} }}\) where \(\delta {\text{a}}^{2} \;{\text{ and}}\; \delta {\text{b}}^{{2}}\) are the community-level and individual-level variance respectively. Individual level variance (\(\delta {\text{b}}^{{^{2} }}\)) is equal to \(\pi^{2}\)/3 which is a fixed value. The median Odds Ratio (MOR) was calculated as MOR = e0.95*\(\sqrt {V{\text{a}}1}\), where Va1 is the variance in the empty model, and Proportional Change in Variance (PCV) was computed as PVC = \(\frac{Va1 - Va2}{{Va1}}\), where Va2 represents the neighborhood variance in the succeeding model and Va1 represents the variance of the empty model. Deviance (-2LL) was used to measure goodness of fit, and the Likelihood Ratio (LR) test was used to compare the models.

Patient and public involvement statement

The general public and patients (participants) were not consulted in the planning or design of the study. Because we used secondary data (DHS), patients were not consulted to interpret the results, nor were they asked to participate in the preparation or editing of this article to ensure its accuracy or readability.

Results

Background characteristics of study participants

A total of 1655 study participants were involved in this study. The majority, 998 (60.2%), of the study participants were in the age group of 15–29. The majority of the women, 218 (13.2%), were from the Amhara region, followed by Tigray with 203 (12.3%) and SNNPR with 200 (12.1%). Regarding educational status, 612 (37.0%) of the respondents had primary education. Concerning marital status, 1523 (92.0%) of the study participants were married (Table 1).

Obstetrics characteristics of the study population

The majority, 1463 (88.4%), of the participants gave birth by spontaneous vaginal delivery. Regarding the frequency of ANC visits, only 157 (9.5%) of the respondents had four or more ANC visits (Table 2).

Respondent’s knowledge of pregnancy complications

In the current study, the majority of the study subjects, 741 (44.8%, CI: 42.4%-47.2%), were found to be knowledgeable about pregnancy complications. Vaginal bleeding was the most frequently mentioned pregnancy complication by the study participants, 1105 (66.8%), followed by severe headache, 856 (51.7%) (Fig. 1).

Associated factors of knowledge about pregnancy complications

The random effect analysis result

According to the ICC in the null model, 17.1% of the total variability in the knowledge of pregnancy complications was attributed to changes between clusters, while the remaining variability was due to variation within clusters. However, the community-level variability decreased to 8.9% when considering both individual and community-level predictors (i.e., in the combined model). Our use of multilevel modeling proved more effective than the conventional single-level regression model, as indicated by the presence of a non-zero ICC in the null model. Furthermore, the variation in knowledge of pregnancy complications between clusters was demonstrated by a MOR of 2.12 in the null model. The proportional change in variance (PCV) of the multilevel model indicated that 53% of the variability in knowledge of pregnancy complications could be explained by the combined effects of individual and community-level factors. Deviance was used to compare models, and model III was identified as the best-fit model with the lowest deviance (Table 3).

The fixed effect analysis result

In the crude multilevel modeling, maternal education, frequency of ANC visits, and administrative region were significantly associated with knowledge of pregnancy complications. Women educated to secondary and higher levels were 1.54 (AOR = 1.54, 95% CI = 1.04–2.29) and 1.74 times (AOR = 1.74, 95% CI = 1.11–2.72) more likely to be knowledgeable about pregnancy complications than women with no education, respectively. The odds of good knowledge about pregnancy complications among women with four or more ANC visits (AOR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.49–0.98) decreased by 26% compared to women with 1–3 ANC visits. Women living in Amhara (AOR = 2.10, 95% CI = 1.24–3.55) and SNNPR (AOR = 3.92, 95% CI = 2.10–7.31) were more likely to have good knowledge about pregnancy complications compared to women residing in Tigray. Conversely, women residing in Harari and Dire-Dawa were 80% (AOR = 0.20, 95% CI = 0.08–0.44) and 52% (AOR = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.24–0.95) less likely to be knowledgeable about pregnancy complications than women living in the Tigray region, respectively (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated women’s knowledge about pregnancy complications in Ethiopia and identified several significant predictors. Our findings indicate that women’s knowledge levels were notably lower compared to those reported in a specific literature review focused on the country. Notably, maternal education, frequency of ANC visits, and administrative region emerged as significant predictors of knowledge about pregnancy complications.

In 2019, the prevalence of knowledge about pregnancy complications in the country was 741 (44.8%). Our study observed a lower prevalence rate compared to several studies conducted in different parts of Ethiopia. Specifically, higher prevalence rates have been reported in Debre Tabor (74.4%)15, Hossana (63.2%)16, Bahir Dar (59%)30, and Mechekel District (55.1%)28. These differences may be attributed to variations in sample sizes, study designs, and regional differences in antenatal care (ANC) utilization. Local socio-cultural factors may also influence knowledge about pregnancy complications, contributing to the observed discrepancies.

In contrast, our findings were higher than those reported in other Ethiopian studies. For example, lower prevalence rates were observed in Shashemane town (40%)9, Nekemte town (32%)20, Goba district (22.1%)19, Afar (7.9%)33, and Wolaita Sodo town (16.8%)18. The variations in these findings could be due to differences in local healthcare practices, levels of health education, and accessibility to ANC services.

When comparing our findings to studies conducted outside Ethiopia, we also observed higher prevalence rates compared to those reported in Tanzania (32%)31 and Rwanda (17%)32. The discrepancies between these international findings and our study may be attributed to differences in healthcare systems, health education levels, and accessibility to ANC services across these countries.

The multilevel analysis revealed that women who educated secondary and higher levels were 1.54 (AOR = 1.54, 95% CI = 1.04–2.29) and 1.74 (AOR = 1.74, 95% CI = 1.11–2.72) times more likely to be knowledgeable about pregnancy complications than women with no education respectively. This finding was supported by studies conducted in Debre Tabor15, Hossana Town19, Goba district19, and Afar33. The observed phenomenon may be attributed to the fact that older women, having experienced obstetric danger signs in previous pregnancies, may possess greater knowledge about these signs during subsequent pregnancies. This underscores the need for young women undergoing their first pregnancy to receive additional attention in counseling and health education. Studies indicate that health education delivered during antenatal care significantly improves mothers’ understanding of obstetric danger signs34.

In this study, the odds of good knowledge about pregnancy complications among women with four and above ANC Visits (AOR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.49–0.98) was decreased by 26% to that of women with 1–3 ANC visits. This finding contrasts with studies conducted in Rwanda32 Goba district19, and Debre Tabor town15. The result indicating decreased knowledge about pregnancy complications among women with four or more ANC visits could stem from increased reliance on healthcare providers for managing their pregnancy, potentially reducing proactive information-seeking behaviors. Additionally, frequent visits might lead to information overload or a perception of comprehensive care, diminishing the perceived need for additional knowledge acquisition. Variations in the quality and content of ANC counseling could further influence the depth of understanding regarding pregnancy complications35.

Furthermore, knowledge of pregnancy complications varied significantly by region. Women residing in Amhara were 2.10 times more likely to have good knowledge (AOR = 2.10, 95% CI = 1.24–3.55), and those in SNNPR were 3.92 times more likely (AOR = 3.92, 95% CI = 2.10–7.31), compared to women residing in Tigray. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in Ethiopia36. Women residing in Harari and Dire-Dawa were 80% and 52% less likely, respectively, to be knowledgeable about pregnancy complications compared to women living in the Tigray region. This discrepancy might be attributed to differences in the socio-cultural characteristics of the regions. Another possible explanation could be variations in ANC utilization between less populated and pastoral regions (Harari and Afar) compared to densely populated regions33,37. Furthermore, the variation may be attributed to the stronger access to healthcare facilities in rural regions and city administrations. This suggests that access to healthcare services could vary across different regions of the country.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study utilized extensive national survey data, providing sufficient statistical power and reliable estimates through sampling weights. By examining knowledge of pregnancy complications at individual/household and community levels, it explored hierarchical influences on outcomes. However, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits causal inferences between knowledge of fertility periods and independent variables. Additionally, reliance on self-reported information introduces the potential for recall bias.

Conclusion

This study found that nearly half (44.8%) of the study participants demonstrated knowledge about pregnancy complications. Maternal education, Frequency of ANC visits, and administrative region were significant predictors of knowledge about pregnancy complications. Such a low level of knowledge may make it more difficult for women who experience pregnancy complications to get access to obstetric care. Enhancing antenatal counseling services and disseminating health information regarding pregnancy complications in the community should be priorities.

Implications of the study

Our study underscores the need for targeted interventions to improve women’s knowledge about pregnancy complications in Ethiopia. Policies aimed at enhancing maternal education, increasing the frequency of antenatal care visits, and addressing regional disparities in healthcare access are crucial. Strengthening community-based health education programs and integrating comprehensive information on pregnancy complications into existing maternal health services can play a pivotal role in improving maternal health outcomes across the country.

Data availability

The article contains all result-based data. Furthermore, the measure DHS Programme provides access to the dataset via https://www.dhsprogram.com.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- EMDHS:

-

Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey

- ICC:

-

Intra Class Correlation Coefficient

- LLR:

-

Log-Likelihood Ratio

- MOR:

-

Median odds ratio

- PVC:

-

Proportional Change in Variance

- SNNPR:

-

Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region

References

Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2020: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division. [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240068759

Maternal mortality. [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality

SDG Indicators — SDG Indicators. [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/regional-groups

Ethiopia at a glance | FAO in Ethiopia | Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture. [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/ethiopia/fao-in-ethiopia/ethiopia-at-a-glance/fr/

EDHS 2016.pdf. [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/ethiopia/media/456/file/EDHS%202016.pdf

knowledge of alarming sign during pregnancy among pregnant woman at selected hospital in Indore, India | International Journal of Nursing and Medical Science (IJNMS) ISSN 2454–6674. 2022 Feb 4 [cited 2024 Jan 11]; Available from: https://internationaljournal.org.in/journal/index.php/ijnms/article/view/580

CDC. Hear Her Campaign: Urgent Maternal Warning Signs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022 [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hearher/maternal-warning-signs/index.html

Exercises to avoid during pregnancy and symptoms of overexertion | BabyCenter. [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.babycenter.com/pregnancy/diet-and-fitness/pregnancy-exercise-warning-signs-to-slow-down-or-stop_7818

Wassihun, B. et al. Knowledge of obstetric danger signs and associated factors: a study among mothers in Shashamane town, Oromia region, Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 17(1), 4 (2020).

ethiopia-fmoh_national-reproductive-health-strategy.pdf. [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.exemplars.health/-/media/files/egh/resources/underfive-mortality/ethiopia/ethiopia-fmoh_national-reproductive-health-strategy.pdf?la=en

Ayele AA, Tefera YG, East L. Ethiopia’s commitment towards achieving sustainable development goal on reduction of maternal mortality: There is a long way to go. Womens Health. 2021 [cited 2024 Jan 11];17. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8689608/

Evaluation of Community-Based Health Insurance Pilot Schemes in Ethiopia: Final Report | HFG. [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.hfgproject.org/evaluation-cbhi-pilots-ethiopia-final-report/

2.-Ethiopia-Health-Sector-Transformation-Plan-I-2015-2020-Endline-Review.pdf. [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: https://ephi.gov.et/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2.-Ethiopia-Health-Sector-Transformation-Plan-I-2015-2020-Endline-Review.pdf

Getachew D, Getachew T, Debella A, Eyeberu A, Atnafe G, Assefa N. Magnitude and determinants of knowledge towards pregnancy danger signs among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Chiro town health institutions, Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med. 2022 [cited 2024 Jul 20];10. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8832609/

Asferie, W. N. & Goshu, B. Knowledge of pregnancy danger signs and its associated factors among pregnant women in Debre Tabor Town Health Facilities, South Gondar Administrative Zone, North West Ethiopia, 2019: Cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. 25(10), 20503121221074492 (2022).

Mesele TT, Syuom AT, Molla EA. Knowledge of danger signs in pregnancy and their associated factors among pregnant women in Hosanna Town, Hadiya Zone, southern Ethiopia. Front Reprod Health. 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 10];5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/frph.2023.1097727

Hibstu, D. T. & Siyoum, Y. D. Knowledge of obstetric danger signs and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care at health facilities of Yirgacheffe town, Gedeo zone, Southern Ethiopia. Arch Public Health. 75(1), 35 (2017).

Knowledge of obstetric danger signs and associated factors among pregnant women in Wolaita Sodo town, South Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study - Alemu Bolanko, Hussen Namo, Kirubel Minsamo, Nigatu Addisu, Mohammed Gebre, 2021. [cited 2024 Jan 10]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/20503121211001161

Bogale, D. & Markos, D. Knowledge of obstetric danger signs among child bearing age women in Goba district, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 15(1), 77 (2015).

Teshoma Regasa, M., Markos, J., Habte, A. & Upashe, S. P. Obstetric danger signs: Knowledge, attitude, health-seeking action, and associated factors among postnatal mothers in Nekemte Town, Oromia Region, Western Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Obstet Gynecol Int. 1(2020), e6573153 (2020).

Gesese SS, Mersha EA, Balcha WF. Knowledge of danger signs of pregnancy and health-seeking action among pregnant women: a health facility-based cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg 2012. 2023;85(5):1722–30.

Does proximity of women to facilities with better choice of contraceptives affect their contraceptive utilization in rural Ethiopia? | PLOS ONE. [cited 2023 Dec 15]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187311

Original research: Modern contraceptive utilisation and its associated factors among reproductive age women in high fertility regions of Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis of Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey - PMC. [cited 2023 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9930559/

Wang, W. & Mallick, L. Understanding the relationship between family planning method choices and modern contraceptive use: an analysis of geographically linked population and health facilities data in Haiti. BMJ Glob Health. 4(Suppl 5), e000765 (2019).

Prevalence and predictors of contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in 17 sub-Saharan African countries: A large population-based study - ScienceDirect. [cited 2023 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1877575619300618?via%3Dihub

FR363.pdf. [cited 2024 Jan 31]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR363/FR363.pdf

CDC. Signs and Symptoms of Urgent Maternal Warnings Signs. HEAR HER Campaign. 2024 [cited 2024 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hearher/maternal-warning-signs/index.html

Amenu, G., Mulaw, Z., Seyoum, T. & Bayu, H. Knowledge about danger signs of obstetric complications and associated factors among postnatal mothers of mechekel district health centers, East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia, 2014. Scientifica. 8(2016), e3495416 (2016).

Salem, A. et al. Cross-sectional survey of knowledge of obstetric danger signs among women in rural Madagascar. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 18(1), 46 (2018).

Jewaro, M., Yenus, H., Ayanaw, Y., Abera, B. & Derso, T. Knowledge of obstetric danger signs and associated factors among mothers in Bahir Dar district, northwest Ethiopia: An institution-based cross-sectional study. Public Health Rev. 41(1), 14 (2020).

Shewiyo EJ, Mjemmas MG, Mwalongo FH, Diarz E, Msuya SE, Leyaro BJ. Does knowledge of danger signs influence use of maternal health services among rural women? Findings from Babati Rural district, Northern Tanzania.

Uwiringiyimana, E. et al. Pregnant women’s knowledge of obstetrical danger signs: A cross-sectional survey in Kigali, Rwanda. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2(11), e0001084 (2022).

Knowledge of pregnancy danger signs and associated factors among pastoral women in Afar Regional State, Ethiopia. [cited 2024 Jan 10]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205X.2019.1612133?needAccess=true

Duysburgh, E. et al. Counselling on and women’s awareness of pregnancy danger signs in selected rural health facilities in Burkina Faso, Ghana and Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 18(12), 1498–1509 (2013).

Grand-Guillaume-Perrenoud, J. A., Origlia, P. & Cignacco, E. Barriers and facilitators of maternal healthcare utilisation in the perinatal period among women with social disadvantage: A theory-guided systematic review. Midwifery. 1(105), 103237 (2022).

Geleto, A., Chojenta, C., Musa, A. & Loxton, D. WOMEN’s knowledge of obstetric danger signs in Ethiopia (WOMEN’s KODE):a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 8(1), 63 (2019).

Harari region .pdf. [cited 2024 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/ethiopia/media/2546/file/Harari%20region%20.pdf

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Measure DHS from the bottom of our hearts for sharing the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, software, investigation and writing were done by BK&WK. Methodology, review, and editing were done by KU and MS . BK drafted the manuscript and all authors have a substantial contribution in revising and finalizing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was not required because the researcher did not interact with the respondents. The data for this study was obtained from the DHS website (www.dhsprogram.com) after requesting authorization online and providing justification for the investigation. No personal identity was present in the publicly accessible data used for this investigation. For more information, visit https://dhsprogram.com/methodology/Protecting-the-Privacy-of-DHS-Survey-Respondents.cfm. The methods employed in this study strictly adhered to the applicable guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lahole, B.K., Mare, K.U., Shewangizaw, M. et al. Analyzing women’s knowledge of pregnancy complications in Ethiopia through a multilevel approach. Sci Rep 14, 24332 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75152-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75152-3