Abstract

Proteinuria is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and acts as a surrogate marker of renal damage. This study aimed to determine the association between changes in proteinuria and the occurrence of CVD. In our study, 1,708,712 participants who consecutively underwent national health examinations from 2003−2004 (first period) to 2005−2006 (second period) were included. They were classified into four groups based on the presence of proteinuria at the two consecutive health examinations: (1) normal (0 → 0), (2) proteinuria-improved (participants who had improved proteinuria (+ 1 → 0, + 2 → ≤ +1 [0 or + 1], ≥ +3 → ≤ +2 [0, + 1 or + 2]), (3) proteinuria-progressed (0 → ≥ +1, + 1 → ≥ +2, + 2 → ≥ +3), and (4) proteinuria-persistent (+ 1 → +1, + 2 → +2, ≥ +3 → ≥ +3). We used a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model to assess the occurrence of CVD according to changes of presence and severity of proteinuria. During a median of 14.2 years of follow-up, 143,041 participants (event rate, 8.37%) with composite CVD were observed. Compared with the normal group, the risk of incident risk of CVD was increased according to the severity of proteinuria in each of the persistent, progressed, and improved groups (p for trend < 0.001). In a pairwise comparison, the risk of composite CVD in the improved (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.32, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.27–1.37), progressed (HR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.44–1.54), and persistent groups (HR: 1.78, 95% CI: 1.64–1.94) were higher than that of the normal group. Furthermore, the improved group had a relatively lower risk of composite CVD compared to the persistent group (HR: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.69–0.83, p < 0.001). The incidence risk of composite CVD was associated with changes of presence and severity of proteinuria. Persistent proteinuria may be associated with increased risk of CVD, even compared with improved or progressed proteinuria status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Although the overall mortality from CVD has decreased in recent decades, it remains substantially high1,2. In 2030, the number of people with CVD is estimated to reach 23 million worldwide. Due to the ongoing increase in the number of elderly patients with cardiovascular problems, the economic burden of CVD may continue to be high3. In addition, CVD has a significant impact on the quality of life and reduces life expectancy. Therefore, there is increasing emphasis on the identification of risk factors for CVD and the importance of prevention. However, information regarding further modifiable associations or the occurrence for CVD is still lacking.

Proteinuria is a significant indicator of renal damage that is observed during the early stages of renal function decline4. The urine dipstick test to identify proteinuria is commonly used in health screening and clinical practice because it is simple, fast, inexpensive, and has acceptable diagnostic accuracy. It can diagnose proteinuria with relatively high specificity and sensitivity (> 90%)5. Previous reports suggested the association between positive dipstick proteinuria and the risk of death, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, coronary heart disease, cognitive impairment, and progression to kidney failure6,7,8,9,10. Previous studies have suggested that proteinuria is not only an independent predictor of CVD development, but also a biomarker to predict mortality in patients with CVD11,12,13. However, changes in proteinuria using a urine dipstick on the risk of CVD are not well known. Few longitudinal studies have targeted the general population with large sample sizes to investigate the association between changes in proteinuria and the occurrence of CVD.

We hypothesized that changes of presence and severity of proteinuria would be associated with the incident risk of CVD. This study aimed to investigate the association of changes presence and severity of proteinuria checked by dipstick test with the occurrence of CVD using a Korean nationwide population-based cohort database.

Results

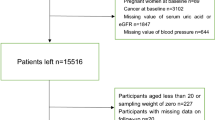

Among the 1,708,712 participants included in this study (Fig. 1), 1,666,681 (97.54%) were categorized as normal, 18,759 (1.10%) as proteinuria-improved, 20,978 (1.23%) as proteinuria-progressed, and 2,294 (0.13%) as proteinuria-persistent. The median interval between the first and second health screening was 21.4 months (interquartile range, 11.0–25.6 months). Baseline characteristics according to changes in dipstick proteinuria status are shown in Table 1. The mean age of overall participants was 44.0 ± 12.1 years, and 69.0% were male. The proteinuria-persistent group consisted of more males than the other groups. Considering the comorbidities, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, cancer, renal disease, and Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) ≥ 2 were the lowest in the normal group and the highest in the proteinuria-persistent group (Table 1).

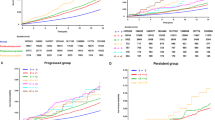

During a median of 14.2 (interquartile range, 11.1–15.3) years of follow-up, 143,041 participants (event rate, 8.37%) with composite CVD were observed. In addition, 109,932 participants (event rate, 6.43%) had all-cause death, 9,285 (event rate, 0.54%) had myocardial infarction (MI), and 17,852 (event rate, 1.04%) had all strokes. The cumulative incidence curve using 1-Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the occurrence of composite CVD, including all-cause death, all strokes (ischemic stroke [IS] and hemorrhagic stroke [HS]), and MI, according to changes in proteinuria status, are shown in Fig. 2 and Figures S1-S5. Throughout the follow-up period, the occurrence of composite CVD was the highest in the persistent group, followed by the progressed, improved, and normal groups (p for trend < 0.001; Fig. 2). These findings were consistent with those of all-cause death, all strokes (IS and HS), and MI (p for trend < 0.001; Figure S1-S5).

In addition, compared with the normal group, the incidence of composite CVD increased with the severity of proteinuria in each of the persistent, progressed, and improved groups (p for trend < 0.001; Table 2). These results were consistent even when all-cause death (p for trend < 0.001) and MI (p for trend < 0.001) were considered as outcomes. However, for all strokes and IS, the dose-response relationship according to the severity of proteinuria was significant only in the persistent group (p for trend < 0.001) but non-significant in the improved (p for trend = 0.062 and 0.095, respectively) and progressed groups (p for trend = 0.071 and 0.096, respectively; Table 2). Furthermore, for HS, the dose-response relationship according to the severity of proteinuria was not statistically significant (Table 2).

In a pairwise comparison, the occurrence of composite CVD in the improved (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.32, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.27–1.37), progressed (HR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.44–1.54), and persistent groups (HR: 1.78, 95% CI: 1.64–1.94) were higher than that of the normal group (Table 3). In contrast, the improved group had a lower risk of composite CVD occurrence than that of the persistent group (HR: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.69–0.82, p < 0.001), and the progressed group (HR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.84–0.93, p < 0.001). Similar trends and results were observed for all-cause death, all strokes (IS and HS), and MI (Table 3).

These trends and results were consistently observed in the sensitivity analysis regarding the change in the presence of proteinuria, regardless of the underlying renal conditions (Tables S1 and S2). Multivariate analysis also showed a relationship between the occurrence of CVD and the severity of dipstick proteinuria in the first and second periods. The relationship between the occurrence of composite CVD and the severity of dipstick proteinuria increased significantly in the order of severity of proteinuria (+ 1, + 2, +3, and + 4), compared to negative proteinuria in the second period (+ 1: 1.41 [1.35–1.46], + 2: 1.66 [1.57–1.75], + 3: 2.13 [1.91–2.39], and + 4: 2.56 [1.99–3.30], p for trend < 0.001, Table S3). A similar association between composite CVD and the severity of dipstick proteinuria in the first period is shown (Table S4). Furthermore, a significantly similar association between all-cause death and MI and the severity of dipstick proteinuria is shown (Tables S3 and S4).

To ensure a balanced comparison between these groups, we additionally perform a 1:4 propensity score matching (PSM) between the normal and proteinuria-persistent groups, between proteinuria-improved and proteinuria-persistent groups, and between proteinuria-progressed and proteinuria-persistent groups, respectively. No major imbalances in baseline covariates were observed between these groups after PSM, as assessed using SMD (all SMD < 0.1; Table S5, S7 and S9). In multivariable analysis, these trends and results were similar after PSM. However, the result for all strokes, IS, and HS based on change in proteinuria between proteinuria-improved and proteinuria-persistent groups and between proteinuria-progressed and proteinuria-persistent groups was not significant (Table S6, S8, and S10).

Discussion

This was a longitudinal, large, nationwide, population-based cohort study, including adults who underwent repeated health checkups in Korea, to evaluate the impact of changes of presence and severity of proteinuria on the risk of CVD. The present study showed the following findings: (1) improvement in proteinuria was associated with decreased risk of the occurrence of composite CVD compared to cases of persistent or progressed proteinuria; (2) the incidence of composite CVD was notably elevated in cases where there was a more pronounced progression of proteinuria or persistent severe proteinuria; (3) Moreover, despite improvements in proteinuria, the risk of CVD rose when initial proteinuria was severe or when improvements were partial; (4) Similar trends were observed for all-cause death and MI, all strokes, and IS, except HS.

Proteinuria, a marker of renal injury, is frequently used as an independent predictor of CVD in various populations with diabetes mellitus and hypertension14,15. Proteinuria is typically evaluated by 24-h urine protein excretion rate or urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio according to guidelines16. However, quantitative confirmatory methods are complex and expensive. Although studies on whether dipstick tests for proteinuria correlate with the urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio are controversial, dipstick proteinuria is frequently used as an inexpensive17. Previous studies have shown that dipstick proteinuria is associated with an increased risk of mortality from CVD and MI18,19,20. However, previous studies have limitations, as proteinuria was assessed only once. Proteinuria can change and can be affected by many factors, including obesity, glucose levels, and blood pressure. Additionally, due to the high false-positive rate which is associated with dipstick proteinuria in the general population, evaluating serial changes in proteinuria may be a useful way to predict the risk of CVD.

A previous study showed that persistent proteinuria, a marker of the continuous impairment of renal function, is a potential risk factor for CVD18. Another study showed that continuous and incident proteinuria are predictors of cardiovascular mortality in a prospective analysis19. Furthermore, a previous study reported a stepwise increase in the risk of stroke and coronary artery disease for transient and continuous proteinuria, evaluated using urine dipsticks21. Additionally, persistent dipstick proteinuria has been identified as an independent risk factor for MI and stroke22,23. Consistent with previous studies, the present study showed that the risk of CVD was highest in the proteinuria-persistent group, followed by the proteinuria-progressed, proteinuria-improved, and normal groups. Additionally, persistent proteinuria increased the risk of CVD compared to those who improved from or progressed proteinuria. Furthermore, we showed a new relationship in which an improvement in proteinuria is associated with a favorable change in the risk of CVD. Therefore, we suggest that participants with positive dipstick proteinuria in the first checkup had a reduced risk of CVD if dipstick proteinuria resolved in the second checkup. This trend is similar to that reported in a previous study that analyzed the association between changes in proteinuria and the occurrence of MI and heart failure in patients with diabetes22,24. However, in multivariable analysis, the result for all strokes, IS, and HS based on change in proteinuria between improved and persistent groups and between progressed and persistent groups was not significant. There is a possibility that persistent proteinuria is more strongly associated with MI and all-cause death compared to all strokes, IS, and HS. Another possibility is that the outcome data might be limited due to a small number of participants.

Although we showed a dose-response relationship between the severity of proteinuria and the incidence of CVD, including all-cause death, all strokes, IS, and MI, the dose-response relationship according to the severity of proteinuria for all strokes, IS, and MI was not significant in the improved groups (+ 1 → 0) and progressed group (0 → +1). It is likely that the results could be due to participants having false-positive results, mild (1+) proteinuria, or occasional proteinuria during the health checkup. Furthermore, the dose-response relationship according to the severity of proteinuria for all strokes was not significant in the improved groups (+ 3 ~ 4 → +1 or + 2) and that for IS was not significant in the improved groups (+ 2 → +1, + 3 ~ 4 → +1 or + 2) and progressed groups (0 → +3 ~ 4, + 1 → +2, + 2 → +3 ~ 4). There is a possibility that the impact of proteinuria on stroke occurrence including progressed and improved groups might be limited due to heterogeneous mechanism of ischemic stroke. Another possibility is that it might be due to a small number of participants who developed outcomes.

The mechanisms underlying the association between changes in proteinuria and the occurrence of CVD are poorly understood. Proteinuria may act as a marker of end-organ damage, endothelial dysfunction, vasculopathy, or cardiometabolic syndrome, leading to atherosclerosis of the arterial walls25,26,27. Also, proteinuria results from the impairment of the glomerular filtration barrier due to the degradation of the endothelial glycocalyx28. This degradation can lead to serum proteins passing through the endothelial fenestrations and enable circulating factors to encounter and activate podocytes29. CVD is induced by systemic endothelial dysfunction, including glomerular endothelial cells. Therefore, proteinuria might serve as an indirect indicator of the extent of endothelial dysfunction30. Further studies are needed to evaluate other markers including hyperuricemia, which are associated with systemic endothelial dysfunction31. Additionally, chronic proteinuria may aggravate oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, thrombogenesis, or activation of the renin-angiotensin system, leading to CVD32,33,34. Furthermore, proteinuria is associated with traditional cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension and diabetes mellitus, which makes it a marker of shared cardiovascular risk factors. Recent studies have also suggested that degradation of the endothelial glycocalyx, which attaches to the vascular endothelium and acts as a barrier against albumin filtration, maybe a significant factor in explaining the mechanism linking proteinuria and CVD35.

There are several limitations to this study. First, this was a retrospective observational study that had several biases, including high selection bias. About 8% of participants had at least 1 data point missing in first and second periods. Although this value is not very high, we conducted s sensitivity analysis (Table S11) comparing participants included in the study with those excluded based at least 1 data point missing. There were no significant differences between the included and excluded groups. However, using the current data we have, we are unable to conduct a sensitivity analysis to adjust for unmeasured confounding issues (e.g. negative control). Because retrospective approach does not provide an accurate number of events, evaluation with prospective follow-up is needed. Second, the present study used a dipstick test to estimate proteinuria. Although urine protein-to-creatinine and albumin-to-creatinine ratios are quantitative, specific, and facilitate the evaluation of relevant changes over time, they pose challenges due to time constraints and cost factors in large epidemiological studies and were not evaluated in the present study. These ratios for further study could be useful for confirming the results of our study. Also, the dipstick method is prone to false positives, especially in low range 1+, and may not remain positive during the 14 year follow up period, which limits to assess the prognostic impact of persistent proteinuria on subsequent CVD. Third, because urine protein-to-creatinine, albumin-to-creatinine ratio, HbA1c, or medication information of patients did not include in NHIS-HEALS dataset, we could not analyze. In addition, because the baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate values of patients in the NHIS-HEALS dataset are available only since 2009, we could not include baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate values in our dataset. Therefore, we cannot present whether the kidney function in the persistent group declined over the 14-year follow-up period. Fourth, our results must be interpreted considering variations in the visual reading of dipstick strips, the role of exercise and infection, and medication intake. Sixth, because the present study was longitudinal and retrospective, we could not confirm causal relationships or exclude confounders. Finally, because this was an epidemiological study, it cannot explain the basic mechanism of the association between proteinuria and CVD.

In conclusion, the incidence risk of composite CVD was associated with changes of presence and severity of proteinuria. Persistent proteinuria may be associated with increased risk of CVD, even compared with improved or progressed proteinuria status.

Methods

Participants

Present study had retrospective cohort design and utilized National Health Insurance Service-Health Screening (NHIS-HEALS) dataset provided by the Korean government. In Korea, participants aged > 40 years undergo free biannual health checkups. Information on the dataset has been previously reported36,37. Briefly, health checkups consisted of a physical examination, lifestyle questionnaire, and laboratory findings, including a urine dipstick test for proteinuria. In our study, 1,878,336 participants who underwent health checkups from 2003−2004 (first period) to 2005−2006 (second period) were included (dataset number NHIS-2021-1-715) through an identification and validation process38,39,40. Among the 1,878,336 participants, those who died before the index date (n = 7) and those who had at least one missing data point (n = 165,234) were excluded. Patients with a history of CVD (n = 4,383) were excluded. Finally, 1,708,712 participants were included in this study (Fig. 2). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ewha Womans University Seoul Hospital (Institutional Review Board approval number: Ewha Womans University Medical Center 2023-05-020). The need for informed consent from individual patients was waived owing to the retrospective nature of the study, with the approval of the Institutional Review Board of the Ewha Womans University Seoul Hospital.

Changes in proteinuria and covariates

As part of the health checkup, a dipstick test was performed to detect proteinuria using urine samples obtained in the morning after an overnight fast. Proteinuria was semi-quantitatively confirmed by interpretation of the dipstick test results based on a color change from yellow to blue. The test results were reported as “0,” “+1,” “+2,” “+3,” or “+4.” In this study, we divided the participants into four groups focused on the presence of proteinuria at the two consecutive health examinations: (1) normal (0 → 0), (2) proteinuria-improved (+ 1 → 0, + 2 → ≤ +1 [0 or + 1], ≥ +3 → ≤ +2 [0, + 1 or + 2]), (3) proteinuria-progressed (0 → ≥ +1, + 1 → ≥ +2, + 2 → ≥ +3), and (4) proteinuria-persistent (+ 1 → +1, + 2 → +2, ≥ +3 → ≥ +3). For the sensitivity analysis, we classified participants according to changes in the presence of proteinuria (Supplementary Method 1).

Detailed definitions of the covariates are presented in Supplementary Methods 2 and previous studies41,42,43. Variables including age, sex, body mass index, household income (first, second, third, or fourth quartile), smoking status (never, former, or current), alcohol consumption (0, < 3, or ≥ 3 days per week), regular exercise (0, < 3, or ≥ 3 days per week), comorbid disease (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, cancer, and renal disease), and CCI, which is a commonly used method for evaluating comorbidities were collected42,44,45. Comorbidities were defined according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes, history of prescriptions, and laboratory findings from the health checkups42,44.

Outcomes

The second health checkup was defined as the index date. The primary outcome was defined as composite CVD, which included all-cause death and all strokes, including IS, HS, and MI. All strokes were defined according to the following two conditions: one or more claims of diagnostic codes of stroke (I60-I63) with at least one claim of brain imaging within 1 month of the date of stroke occurrence. In addition, MI was diagnosed on the basis of one or more claims of the diagnostic codes for MI (I21). Previously, the diagnostic accuracy of the ICD-10 code (I60-I63) for IS and HS and the ICD-10 code (I21) for MI using the NHIS dataset has been validated44,46. Monitoring was performed until December 31, 2020 or the first occurrence of all-cause death, all strokes, or MI.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables were used to analyze the statistical differences in baseline characteristics between the participants of the four groups according to changes in dipstick proteinuria. The cumulative incidence curve using 1-Kaplan–Meier survival curves with the log-rank test were used to evaluate the relationship between changes in dipstick proteinuria and the occurrence of composite CVD. The Cox proportional hazards model, presented as a HR with a 95% CI, was used to assess the effects of the change of presence and severity of proteinuria between the first and second periods on the occurrence of composite CVD, including all-cause death, all strokes (IS and HS), and MI, after adjusting for all potential confounding factors. A stratified analysis was performed to evaluate the combined effects of renal disease. A pairwise comparison analysis was performed to assess the altered risk of composite outcomes in those who recovered from or developed proteinuria. PSM was additionally applied to mitigate confounding factors in observational studies. In this study, a 1:4 PSM ratio was employed between groups and multivariable Cox analysis was used to compute the propensity scores in a logistic model. All covariates were incorporated into the PSM model. The adequacy of PSM was evaluated using Standardized Mean Differences (SMDs), with PSM deemed appropriate when the absolute values of the SMDs were < 0.1. Statistical analyses were performed using the R software, version 3.3.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SAS (version 9.4; SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Two-sided p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the NHIS-HEALS, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and hence they are not publicly available. However, the data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the National Health Insurance System. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Roth, G. A. et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular diseases and Risk factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 76, 2982–3021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010 (2020).

Amini, M., Zayeri, F. & Salehi, M. Trend analysis of cardiovascular disease mortality, incidence, and mortality-to-incidence ratio: Results from global burden of disease study 2017. BMC Public. Health 21, 401. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10429-0 (2021).

Lozano, R. et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380, 2095–2128. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 (2012).

Cravedi, P. & Remuzzi, G. Pathophysiology of proteinuria and its value as an outcome measure in chronic kidney disease. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 76, 516–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12104 (2013).

Lim, D. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of urine dipstick for proteinuria in older outpatients. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 33, 199–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.krcp.2014.10.003 (2014).

Hillege, H. L. et al. Urinary albumin excretion predicts cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality in general population. Circulation 106, 1777–1782. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000031732.78052.81 (2002).

Hemmelgarn, B. R. et al. Relation between kidney function, proteinuria, and adverse outcomes. JAMA 303, 423–429. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.39 (2010).

Bello, A. K. et al. Associations among estimated glomerular filtration rate, proteinuria, and adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 6, 1418–1426. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.09741110 (2011).

Park, B. S. et al. Alterations in structural and functional connectivities in patients with end-stage renal disease. J. Clin. Neurol. 16, 390–400 (2020).

Toyoda, K. Cerebral small vessel disease and chronic kidney disease. J. Stroke 17, 31–37. https://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2015.17.1.31 (2015).

Agrawal, V., Marinescu, V., Agarwal, M. & McCullough, P. A. Cardiovascular implications of proteinuria: An indicator of chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 6, 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2009.11 (2009).

Matsushita, K. et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: A collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet (London England) 375, 2073–2081. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60674-5 (2010).

Kim, H. J. et al. A low baseline glomerular filtration rate predicts poor clinical outcome at 3 months after Acute ischemic stroke. J. Clin. Neurol. 11, 73–79 (2015).

Wang, A. et al. Proteinuria and risk of stroke in patients with hypertension: The Kailuan cohort study. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich Conn) 20, 765–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.13255 (2018).

Soejima, H. et al. Proteinuria is independently associated with the incidence of primary cardiovascular events in diabetic patients. J. Cardiol. 75, 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjcc.2019.08.021 (2020).

Rossing, P. et al. KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 102(S1-S127). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2022.06.008 (2022).

Mejia, J. R. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of urine dipstick testing for albumin-to-creatinine ratio and albuminuria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 7, e08253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08253 (2021).

Nagata, M. et al. Prediction of cardiovascular disease mortality by proteinuria and reduced kidney function: Pooled analysis of 39,000 individuals from 7 cohort studies in Japan. Am. J. Epidemiol. 178, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kws447 (2013).

Pesola, G. R. et al. Dipstick proteinuria as a predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in Bangladesh: A prospective cohort study. Prev. Med. 78, 72–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.07.009 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Dipstick proteinuria and risk of myocardial infarction and all-cause mortality in diabetes or pre-diabetes: A population-based cohort study. Sci. Rep. 7, 11986. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12057-4 (2017).

Madison, J. R. et al. Proteinuria and risk for stroke and coronary heart disease during 27 years of follow-up: The Honolulu Heart Program. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 884–889. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.8.884 (2006).

Wang, A. et al. Changes in proteinuria and the risk of myocardial infarction in people with diabetes or pre-diabetes: A prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 16, 104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-017-0586-7 (2017).

Park, S. K. et al. The association between changes in proteinuria and the risk of cerebral infarction in the Korean population. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 192, 110090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2022.110090 (2022).

Lee, S. E., Yoo, J., Choi, H. S., Han, K. & Kim, K. A. Two-year changes in Diabetic kidney Disease phenotype and the risk of Heart failure: A Nationwide Population-based study in Korea. Diabetes Metab. J.https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2022.0096 (2023).

Stehouwer, C. D. A. & Smulders, Y. M. Microalbuminuria and risk for cardiovascular disease: Analysis of potential mechanisms. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17, 2106–2111. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2005121288 (2006).

Ito, S., Nagasawa, T., Abe, M. & Mori, T. Strain vessel hypothesis: A viewpoint for linkage of albuminuria and cerebro-cardiovascular risk. Hypertens. Res. 32, 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2008.27 (2009).

Deckert, T., Feldt-Rasmussen, B., Borch-Johnsen, K., Jensen, T. & Kofoed-Enevoldsen, A. Albuminuria reflects widespread vascular damage. Steno Hypothesis Diabetol. 32, 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00285287 (1989).

Bauer, C. et al. Minimal change disease is Associated with endothelial glycocalyx degradation and endothelial activation. Kidney Int. Rep. 7, 797–809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2021.11.037 (2022).

Grahammer, F., Schell, C. & Huber, T. B. The podocyte slit diaphragm–from a thin grey line to a complex signalling hub. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 9, 587–598. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2013.169 (2013).

Yilmaz, M. I. et al. The effect of corrected inflammation, oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction on fmd levels in patients with selected chronic diseases: A quasi-experimental study. Sci. Rep. 10, 9018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65528-6 (2020).

Maruhashi, T., Hisatome, I., Kihara, Y. & Higashi, Y. Hyperuricemia and endothelial function: From molecular background to clinical perspectives. Atherosclerosis 278, 226–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.10.007 (2018).

Fort, J. Chronic renal failure: A cardiovascular risk factor. Kidney Int. Suppl. 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09906.x (2005).

Yilmaz, M. I. et al. ADMA levels correlate with proteinuria, secondary amyloidosis, and endothelial dysfunction. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19, 388–395. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2007040461 (2008).

Stehouwer, C. D. et al. Increased urinary albumin excretion, endothelial dysfunction, and chronic low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes: Progressive, interrelated, and independently associated with risk of death. Diabetes 51, 1157–1165. https://doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1157 (2002).

van den Berg, B. M., Spaan, J. A., Rolf, T. M. & Vink, H. Atherogenic region and diet diminish glycocalyx dimension and increase intima-to-media ratios at murine carotid artery bifurcation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 290, H915–920. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00051.2005 (2006).

Park, M. S., Jeon, J., Song, T. J. & Kim, J. Association of periodontitis with microvascular complications of diabetes mellitus: A nationwide cohort study. J. Diabetes Complicat. 36, 108107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2021.108107 (2022).

Chang, Y. et al. Improved oral hygiene care and chronic kidney disease occurrence: A nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. Medicine 100, e27845. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000027845 (2021).

Kim, J., Kim, H. J., Jeon, J. & Song, T. J. Association between oral health and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with hypertension: A nationwide cohort study. J. Hypertens. 40, 374–381. https://doi.org/10.1097/hjh.0000000000003022 (2022).

Chang, Y., Lee, J. S., Lee, K. J., Woo, H. G. & Song, T. J. Improved oral hygiene is associated with decreased risk of new-onset diabetes: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Diabetologia 63, 924–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05112-9 (2020).

Woo, H. G., Chang, Y. K., Lee, J. S. & Song, T. J. Association of Periodontal Disease with the occurrence of Unruptured cerebral aneurysm among adults in Korea: A Nationwide Population-based Cohort Study. Medicina 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57090910 (2021).

Park, J. et al. Association of atrial fibrillation with infectivity and severe complications of COVID-19: A nationwide cohort study. J. Med. Virol. 94, 2422–2430. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27647 (2022).

Kim, H. J. et al. Associations of heart failure with susceptibility and severe complications of COVID-19: A nationwide cohort study. J. Med. Virol. 94, 1138–1145. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27435 (2022).

Lee, K. et al. Oral health and gastrointestinal cancer: A nationwide cohort study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 47, 796–808. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13304 (2020).

Chang, Y., Woo, H. G., Park, J., Lee, J. S. & Song, T. J. Improved oral hygiene care is associated with decreased risk of occurrence for atrial fibrillation and heart failure: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 27, 1835–1845. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319886018 (2020).

Sundararajan, V. et al. New ICD-10 version of the Charlson comorbidity index predicted in-hospital mortality. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 57, 1288–1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.03.012 (2004).

Choi, E. K. Cardiovascular Research using the Korean National Health Information Database. Korean Circulation J. 50, 754–772. https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2020.0171 (2020).

Funding

This work was supported by the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2022-0-00621, RS-2022-II220621, Development of artificial intelligence technology that provides dialog-based multi-modal explainability). This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: RS-2023-00262087 to TJS). The funding source had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Research conception and design, H.G.W., M.S.P., T.J.S.; Data acquisition, H.G.W., M.S.P., T.J.S.; Data analysis and interpretation, H.G.W., M.S.P., T.J.S.; Statistical analysis, H.G.W., M.S.P., T.J.S.; Drafting the manuscript, H.G.W., M.S.P., T.J.S.; Critical revision of the manuscript, H.G.W., M.S.P., T.J.S.; all authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Woo, H.G., Park, MS. & Song, TJ. Persistent proteinuria is associated with the occurrence of cardiovascular disease: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Sci Rep 14, 25376 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75384-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75384-3