Abstract

Recovering energy from biomass and treating organic waste can be done effectively through a biogas digester system. However, monitoring the performance and control of the system to produce biogas is possible through the online process. Therefore, this study developed a novel low-cost gas and temperature profiling system (GTPS) and data acquisition system (DAS) used in biogas digester. The GTPS is designed to monitor and record the amount of methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2), the main constituent of biogas, from 0 to 100% and to measure the slurry temperature in the digester using a K-type thermocouple. To test the developed monitoring system, the biogas yield (%) and temperature were monitored, and the result obtained agreed with that reported and obtained in the literature (50–70% and 30−40%) for CH4 and CO2, respectively, followed by the desired mesophilic temperature condition for biogas production (20–35 °C). The study employed an RS-232/RS-485 converter for data communication and a low-cost thermocouple module (isolated analog input) that was installed in the data acquisition system. Interestingly, the application of the converter equipment has never been used in any study on monitoring a biogas digester.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Temperature profiles provide information on the heat distribution within a biogas digester system. Heat distribution within a digester has been noted to depend on factors ranging from design parameters to operational and environmental factors. These factors, such as temperature, insulating materials, and mode of feeding, influence the efficiency of the biogas conversion process. Hence, the heating value of the biogas and temperature are considered factors in determining the efficiency and output of the biogas digester1. The current cost of GTPS influences environmental protection and saves energy2. However, there is growth in demand for such a system, particularly for cheap and reliable methane and carbon dioxide sensors of medium precision for biogas monitoring. Biogas monitoring systems using the same and similar sensors cost around 1500–2838.41 USD on average, according to Cruz et al.3, as well as the VTI Valtronic and Eaton MTL. Optical sensors have been identified as a viable technique for monitoring single biogas yield, mainly methane and carbon dioxide4. Also, it detects infrared absorption in the wavelength characteristic of these molecules4. In addition, the composition of biogas was measured using a gas infrared analyzer like the GASCARD II infrared sensor from Edinburgh Instrument5,6. The model 6500 visible/near-infrared scanning monochromatic in FOSS NIR System6 and Siemens Ultra Mat 22P7 operate on the principle of non-dispersive absorption of infrared. These sensors are characterized by high cost and difficulty in installation at biogas production sites. These sensors are around $20,000 at current market prices. In contrast, the estimated cost of the gas sensor used in this study is around $1500, which is the motivation behind this study. However, previous studies have employed varying technologies to monitor gas yield (%) and temperature profiles during anaerobic digestion. For Instance, Mandal et al.8 used a thermocouple probe and an analogue temperature indicator to determine the temperature of the steady-state flame.

In Rego et al.9 and Rego et al.10 study, a perm-selective membrane and pressure transducer were used to determine the composition of methane and carbon dioxide in the volume of 0–100% range. Gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (FID) and electronic capture detector (ECD) are alternative devices for sensing methane and carbon dioxide. Usually, infrared absorption measurements are used to monitor CH4 and CO2 production in volume. On the other hand, hydrogen analyzers have been used based on the electrochemical cells11,12.

These hydrogen analyzers expressed the methane and carbon dioxide values in part per million (ppm) and are known to be expensive. The involvement of diverse microbial activities and communities supports biochemical reactions (hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis) in an anaerobic digester, resulting in instability13. To address this, designing and building a control monitoring system helps to maintain and improve the stability and efficiency of anaerobic digestion14; Boe et al.15 and Li et al.16, as well as developing cost-effective online monitoring methods17. The GTPS presents the volume composition of the gases (CH4 and CO2) and temperature monitoring, whereas the DAS provides the capability to store the data generated. Hence, both systems are known as low-cost units.

Previous studies on the monitoring system of the biogas digesters are usually off-line methods and also carried out manually, such as the gas chromatograph (GC)18 and the mid-infrared spectroscopy method19. These are said to be complex, expensive, and time-consuming. Also, in most cases, some of the sensors for biogas monitoring are used as a single system (biochemical systems)20,21. Hence, this requires further improvement. Therefore, this study aims to integrate various gas sensors, including thermocouples, as a low-cost unified system that will assist in online monitoring of the CH4 and CO2 yield and temperature profiles in a biogas digester. A good monitoring and control system improves the stability of the process and biogas digester performance.

Materials and methods

Site overview

This study was conducted on-site at the Research Centre of the Fort Hare Institute of Technology Alice Campus of Fort Hare University. The exact geographical coordinates of the site are Latitude 32° 47′ 1.28″ S, longitude 26º 51′ 15.10″ E, altitude 1905 feet. In summer (November to March), the average temperature is between 25 and 30 °C. Winters (May to August) are quite cold, with an average temperature of 10–15 °C, but spring and autumn are sunny, warm, and pleasant seasons. The annual average rainfall and temperature of the study area is around 713 mm and 15–25 °C.

Experimental

Biogas digester description

The digester was made from a plastic material of high-density polyethylene (HDPE), with a volume of 2.15 m3, whereas the inlet and outlet chambers were made of brick and cement mortar. The dimensions of both chambers were 895 mm × 985 mm and 1290 mm × 1430 mm in height and width, respectively. For proper feeding of the biogas digester, the chamber (inlet) where the feed is introduced is designed to connect the digester via a 110 cm long PVC pipe with an inclination angle of 28 °C. It was necessary to fabricate the digester cover with HDPE plastic material to withstand harsh weather and environmental conditions, thereby maintaining the conditions required for anaerobic digestion. A K-type thermocouple was used to monitor the gas temperature and slurry inside the biogas digester. The study was conducted during the spring season (October/November) under mesophilic temperature conditions within 25–35 °C22.

Preparation of the substrate

100 kg of cow dung was diluted with 100 L of water in a ratio of 1:1 (waste to water) to form a slurry. In the first feeding, 200 L of the slurry was introduced into the biogas digester, and the gas valve was left open for 3 days to remove air. Afterwards, 50 L of cow dung slurry was fed every 3 days to allow the material to digest and to avoid the rushing of the slurry from the outlet. Cow manure was characterized to determine its physicochemical properties before entering the digestion chamber. These include total solids (130,800 g L− 1), volatile solids (110,476 g L− 1), pH (7.83), chemical oxygen demand and calorific value of 42,583 g L− 1, respectively and 27.00 MJ g− 122,23.

Design and building of a GTPS and DAS

The methodology of this study majorly includes the GTPS and DAS design. The GTPS consists of a non-dispersive infrared (NDIR), pressure sensor, air pump, hydrophobic filter, and thermocouple module, while the DAS includes a data logger, power supply, circuit breaker, and converter. The gas sensors were fitted with hydrophobic filters or bacterial vents connected to each gas inlet to avoid the passage of aerosols and water vapour. One of the precautions taken to protect gas cells from aerosol damage during the study was using filters.

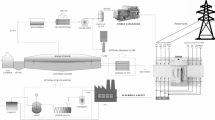

The schematic design and electrical connection of the GTPS and the DAS are presented in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively. Furthermore, the data acquisition system was powered from the control unit, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

With the aid of the schematic design layout of the GTPS and DAS, as shown in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4 show the DAS and GTPS. The DAS consists of the power supply unit (PSU), battery back-up of 12VDC, CR 1000 data logger, MMINTCONV-. intelligent RS-232/RS-485 converter and the relay (See Fig. 3). The relay sets the air pump, which operates for four minutes every hour. This is to prevent the premature failure of the pump as a result of high voltage or current due to overheating. Thus, if not regulated, it damages the system. Besides, to convert the data communication signal of RS-232 for transmission to RS-485, the authors use MMINTCONV, a serial converter unit. The communication protocol between the RS-232 and RS-485 converter is known as the MODBUS. The MODBUS is usually employed for the transmitting of information between devices connected to the network over a serial line or ethernet, thereby increasing its wireless. Additionally, it is a request-response protocol implemented using a master-slave relationship. The main function of the DAS was to store data and supply power to the data acquisition module and the gas cell.

Data acquisition system23.

In Fig. 4, it is imperative to state that the data acquisition module was employed to minimize the voltage drop and interference that might affect the measurements from the gas cell to data acquisition. Hence, its benefits include.

-

Reduction in the cost of the data acquisition system.

-

Simplicity in connection and the wiring were equal, and.

-

Data was in one central location.

The designed GTPS is an affordable device that can monitor CO2 and CH4 gases and the temperature at various points of the digester. The two NDIR gas sensors, three type K thermocouples, a pressure sensor, and an air pump make up the GTPS, which are shown in Fig. 5.

Gas temperature profiling system23.

Description of the components used in the design and building of DAS and GTPS

The following components were used to successfully design and build the data acquisition system and its control unit to ensure the accurate and efficient collection of data.

MMINTCONV- Intelligent RS-232/RS-485 Converter

The RS-232 data communication signal was converted for transmission over 2 or 4 wires twisted pair cables via MMINTCONV- Intelligent RS-232/RS-485 converter. Additionally, the converter could communicate with the RS-232/RS-485 devices and extend the limited distance capabilities of the RS-232 devices. This was done by positioning the module converter plug directly on a DIN rail and isolating the RS-232 and RS-485 signals to prevent ground loops between online devices. The port was configurable via an 8-way dipswitch. The intelligent RS-232/RS-485 converter had the following specifications for its operation. These included but limited to.

-

Power requirement: 200–260VAC, 50/60Hz – LED POWER indication.

-

Operating temperature: – 20 °C to 80 °C.

-

Medium of transmission of 2 or 4-wire twisted pair cable.

-

Dimension of 105 mm (high) × 70 mm (wide) × 60 mm (Dep).

-

Data bit of – 7 or 8 data bits per port.

Isolated analogue inputs: Figure 6 shows the thermocouple modules used in the study. This was provided as PM8AI/I (current input module) or PM8AI/V (voltage input module). The default setting for the PM8AI/I was 0–20 mA, representing 0–4095 volts output value (12-bit). An offset switch was switched on to obtain a 0–4095 volts output value with an input signal of 4–20 mA. Thereafter, PM8AI/I was configured for an input range of 0–20,000 mA. For the voltage input modules, an input voltage of 0−

10 volts represents an output of 0–4095, where 2 volts equals 819 ± 1LSB. However, a 0–4095 volts output value was obtained for a 2–10 volts input signal when switching on the offset switch. Specifications for the PM8AI/I ISO and PM8AI/V ISO are as follows.

-

Logic voltage power supply of 12–24 Vdc and logic current power supply of 58 mA at 12 V/31 mA.

-

PM8AI/V: input points (8), input voltage of 0 (2) to 10 Vdc.

-

PM8AI/I: input point (8) input current of 0 (4) to 20 mA.

-

Operating temperature (– 40 °C to 80 °C) and storage temperature (− 40 °C to 85 °C).

-

Isolation of 1500 Vrms (between field and logic) and 350 volts (peak between each input for voltage inputs), 1000 Vrms (between field and logic), and 350 volts (between each point for current inputs).

-

Connectors: 4 pins connector on the underside of the unit for logic power and an 18-way screw connector on the front for the input.

NDIR gas sensor

The NDIR is a gas detection system used to monitor the rate of biogas yield in percentage. Specifically, it sensed the methane and carbon dioxide concentration, with a full-scale range of 0–100%. Furthermore, it provides a linear output of 0–1 VDC and 4–20 mA in relation to the concentration of CH4 and CO2. The electro-optical gas sensor contained a 1/8 hose barb, which enabled gas flow into the optical path to be analyzed using the NDIR method. This type of sensor was chosen based on the fast response time, accuracy, and a better sensitivity of 20–50 ppm (parts per million). It consisted of the following components: a sample chamber, a wavelength filter, and an infrared detector. The electronic-optical gas sensor contained a 1/8 hose barb that allowed gas to flow into the optical path, and it was analyzed using the NDIR method. In that case, it consists of a sample chamber, infrared detector, and wavelength filter. Gas sensors were operated by pumping or diffusing gas into the sample chamber, and the gas concentrations were measured electro-optically using specific infrared (IR) wavelengths. IR light was then concentrated towards the sample chamber and sent to the detector. The front of the detector contained an optical filter that removed all light except wavelengths that the selected gas molecules could absorb. The sensor was connected to a data logger that measured gas levels over time.

Advantages of NDIR

The NDIR gas sensor has the following advantages:

-

The physical servicing techniques are not affected by an aggressive chemical environment.

-

Gases are detected in anaerobic conditions.

-

It does not detect hydrogen.

-

There is a stable, long-term operation with less recalibration and.

-

CO2 is detected with no inference from other gases.

Properties of Non-dispersive Infrared Gas Sensor (NDIR)

The NDIR gas sensor was chosen over other sensors because of its properties.

-

Free from cross-interference and high selectivity.

-

Sensitivity with accuracy.

-

The absence of negative memory affects or exposes hysteresis.

Design specification of the NDIR gas sensor

-

Range: 0 to 100% volume; Storage temperature: -40 to + 70 °C; Repeatability: ± 1% of full scale.

-

The accuracy is ± 5% of reading (± 2.0% CO2 from 0 to 50% CO2) and ± 2.5% CH4 from 0 to 50% CH4.

-

Operating temperature range: 0 to 50 °C.

-

The external power source is 12 Volts DC at 0.6 amps.

-

The PC board has an external dimension of 3.9 × 5 × 1.5 (in inches).

-

Relative humidity range of 5 to 95% (non-condensing).

-

Output signals for voltage output are 0 to 1 V (full-scale CH4 and CO2) and current output of 4 to 20 mA (full-scale CH4 and CO2).

The following wiring process was used as a guide for the connection of the gas sensor.

-

12VDC power input, usually positive.

-

At the ground, the common/return for 12VDC.

-

+ 0 to 1VDC output.

-

At the ground, the common/return for 4 to 20 Ma and 0 to 1VDC.

Results and discussion

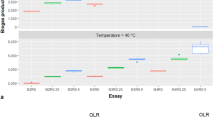

The GTPS system was designed to sense CH4 and CO2 gases in volume and the temperature inside the digester chamber. The interaction or activities of anaerobic bacteria in the presence of moisture and the absence of oxygen give rise to biogas production. The percentage of the gas yield reported from the biogas digester was measured using an NDIR gas sensor over 18 days of monitoring. The gas profile is presented in Fig. 7.

Figure 7 shows that the gas yield for CO2 exceeded CH4 yield by approximately 10% for the first 5 days. This agrees with the literature because carbon dioxide is a product resulting from the first stage (hydrolysis) of anaerobic decomposition24. This is the stage in which complex organic materials are disintegrated to produce carbon dioxide alongside simple sugar, acetic acid, lactic acid, peptides, glycerol, butanoic acid, and other non-organic materials. From the 6th day, as observed in Fig. 7, it is evident that methane fermentation has been fully activated as CH4 yield surpasses CO2. At this stage, the bacteria known as methanogens are entirely disintegrating the organic acids into methane. The maximum methane and carbon dioxide compositions were 60% and 35%, respectively, which is similar to what the literature has for the composition of methane and carbon dioxide (50−70% and 30−40%) for biogas yield (see Table 1) as seen in Cruz et al.3.

The variation of ambient temperature to retention time, as monitored using a type K thermocouple, is presented in Fig. 8.

Figure 8 shows the ambient temperature plot against the biodigester’s retention time. It was observed that ambient temperature varied between 11 and 24 °C of the retention period. The maximum temperature was recorded on the 16th day, while the minimum was recorded on the 11th day. Changes in the study site’s weather conditions cause ambient temperature fluctuation. This agrees with a comparative study of biogas production for different animal slurry25,26. The ambient temperature fluctuation also resulted in a slurry temperature fluctuation, as shown in Fig. 9. The walls of the biogas digester are said to be in direct contact with the atmosphere. Based on this, ambient temperature affects the digestion rate of biogas production. In that case, this gives rise to the digester’s ability to absorb or release heat depending on the temperature difference between the digester and the environment. Therefore, the biogas digester chamber’s heat loss or heat gain rate affects microbial activity inside the chamber’s slurry. Figure 9 shows the influence of temperature on biogas yield measured in °C and %, respectively.

Slurry bottom temperature was observed to vary from 10 to 34 °C from day 6 to day 16 of retention time. The gas yield improved but fluctuated due to the environment’s ambient temperature at the specific temperature gradient. The CH4 and CO2 compositions varied from 10 to 60% and 20–35%, respectively. As shown in Fig. 9, maximum percentage compositions of 60% and 35% for CH4 and CO2 compositions were recorded on day 12 within the mesophilic temperature range of 35 °C and 28 °C, respectively. This corresponds to a study on long-term temperature measurements of fermentation sludge from biogas fermenters carried out by Nekhubvi and Tinarwo26. The study reported the temperature profile results in a fixed dome biogas digester using K-type thermocouples. The maximum percentage of CH4 obtained is close to 67.9% of CH4 reported by Nekhubvi and Tinarwo26 for cow dung digestion. As observed in Fig. 9, fluctuation in gas yield can be attributed to the bacteria activity in the bottom slurry temperature that stopped due to the fluctuating ambient temperature. The methanogen later adjusted to a new temperature, generating heat and fluctuating the bottom slurry temperature. Hence, biogas production started increasing rapidly. The mesophilic temperature is favorable for biogas production due to the active bacteria at that temperature range, which is known as the methanogen. These methanogens entirely disintegrate the organic acids to form CH4.

Conclusions

The study successfully designed and built a low-cost GTPS and DAS monitor and stored the data generated from the biogas digester. The system was designed as an alternative to the high equipment cost and an off-line/manual method of monitoring the performance of the biogas digester, thereby improving biogas production, stability, and efficiency. Interestingly, the system obtained and recorded the result, which agreed with the literature for CH4 and CO2, as 50–70% and 30–40%, respectively. However, this study applies to monitoring residential thermal performance using thermocouples connected to the system. However, as regards the optimization, many biogas digesters will demand detailed process optimization apart from the monitoring alone. Hence, this study’s monitoring techniques and equipment will continue to be developed and refined to support a new modernized system with higher efficiency and low biogas production cost. Furthermore, the design specification of every component or device used in the study was considered during the design study. The measurements or results obtained were highly credible and accurate with such specifications.

Future study and recommendation

The study recommends a detailed economic feasibility study as a future study on implementing the developed GTPS and DAS.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Mamphweli, S. & Meyer, L. Performance monitoring system for a biomass gasifier. J. Eng. Des. Technol. II(1), 7–8 (2013).

Silveira, J. P., Anguita, J., Briones, F., Grasdepot, F. & Bazin, A. Micromachined methane sensor based on low-resolution spectral modulation of IR absorption radiation (1998).

Cruz, I. A. et al. A new approach using an open-source low cost system for monitoring and controlling biogas production from dairy wastewater. J. Clean. Prod. 241, 118284 (2019).

Hoppe, M., Schley, P. & Uhrig, M. Meteorological issues in energy measurement on biogas. Accred. Qual. Assur. 14, 677–683 (2009).

Edinburgh sensor. The anaerobic digestion of biowaste in developing countries. News and Events (2022).

Pierna, J. A., Vermeulen, P., Lecler, B., Baeten, V. & Dardenne, P. Calibration transfer from dispersive instruments to handheld spectrometers. Appl. Spectrosc. 64(6), 644–648 (2010).

Cadena-Pereda, R. O., Rivera-Muñoz, E. M., Herrera-Ruiz, G., Gomez-Melendez, D. J. & Anaya-Rivera, E. K. Automatic carbon dioxide-methane gas sensor based on the solubility of gases in water. Sensors 12(8):10742–10758 (2012).

Mandal, T., Kiran, B. A. & Mandal, N. K. Determination of the quality of biogas by flame temperature measurement. Energy Convers. Manag. 40, 1225–1228 (1999).

Rego, R. & Mendes, A. Carbon dioxide/methane gas sensor based on the perm-selectivity of polymeric membranes for biogas monitoring. Sens. Actuators B. 103, 2–6 (2004).

Rego, R., Caetano, N. & Mendes, A. Development of a new gas sensor for binary mixtures based on the perm-selectivity of polymeric membranes: Application to carbon dioxide/methane and carbon dioxide/helium mixtures. Anal. Chim. Acta. 511, 215–221 (2005).

Mathiot, S. et al. Control parameter variation in an anaerobic fluidised bed reactor subjected to organic shock load. Water Sci. Technol. 25(7), 93–101 (1992).

Pauss, A., Guiot, S., Dochain, D. & Perrier, M. Hydrogen is a key parameter for the monitoring and control of methane production processes. In Proceeding Workshop on Modelling, Monitoring, and Control of Wastewater Treatment Processes, Vol. 58, 2011–2017 (Med. Fac. Landbouww. Univ. Gent, 1993).

Yadav, M. et al. Organic waste conversion through anaerobic digestion: A critical insight into the metabolic pathways and microbial interactions. Metab. Eng. 69, 323–337 (2022).

Dedgaonkar, S., Mohire, A., Jadhav, A., Pawar, S. & Bane, R. Biogas monitoring system for measuring volume using a microcontroller and GSM. Int. J. Curr. Eng. Technol. 6(5) (2016).

Boe, K., Batstone, D. J., Steyer, J. P. & Angelidaki, I. State indicators for monitoring the anaerobic digestion process. Water Res. 44(20), 5973–5980 (2010).

Li, L., Peng, X., Wang, X. & Wu, D. Anaerobic digestion of food waste: A review focusing on process stability. Bioresour. Technol. 248, 20–28 (2018).

Wu, D. et al. Anaerobic digestion: A review on process monitoring. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 103, 1–2 (2019).

Ward, A. J. et al. Real time monitoring of a biogas digester with gas chromatography, near-infrared spectroscopy, and membrane-inlet mass spectrometry. Bioresour. Technol. 102(5), 4098–4103 (2011).

Falk, H. M., Reichling, P., Andersen, C. & Benz, R. Online monitoring of concentration and dynamics of volatile fatty acids in anaerobic digestion processes with mid-infrared spectroscopy. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng.38, 237–249 (2015).

Yantidewi, M., Deta, U. A. & Lestari, N. A. A real-time system for monitoring methane level in biogas production a preliminary study. In International Conference on Science and Technology (ICST 2018) 192–195 (Atlantis Press, 2018).

Guo, P., Zhou, J., Ma, R., Yu, N. & Yuan, Y. Biogas production and heat transfer performance of a multiphase flow digester. Energies. 12(10), 1960 (2019).

Obileke, K., Mamphweli, S., Meyer, E. L., Makaka, G. & Nwokolo, N. Design and fabrication of a plastic biogas digester for the production of biogas from cow dung. J. Eng. 2020, 1–1 (2020).

Obileke, K. et al. Comparative study on the performance of aboveground and underground fixed-dome biogas digesters. Chem. Eng. Technol. 43(1), 68–74 (2020).

Ukpabi, C., Okorie, N., Oriaku, O., Isu, J. & Peters, E. The production of biogas using cow dung and food waste. Int. J. Mater. Chem. 7(2), 21–24 (2017).

Ukpai, P. A. & Nnabuchi, M. N. Comparative study of biogas production from cow dung, cowpea and cassava peeling using 45 litres biogas digester. Adv. Appl. Sci. Res. 3(3), 1864–1869 (2012).

Nekhubvi, V. & Tinarwo, D. Long-term temperature measurement: Biogas digesters fermenting slurry. J. Energy South. Afr. 28(3), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.17159/2413 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge all the necessary assistance and support from the RNA (Renewable Energy-Wind) of the Govan Mbeki Research and Development Centre (GMRDC), University of Fort Hare, the National Research Foundation (NRF) and the Department of Science and Innovation (DSI) as well as the staff of Fort Hare Institute of Technology (FHIT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.O.: Conceptualization, Writing-Original draft preparation, Writing-Reviewing and Editing. E.L.M.: Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. G.M.: Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Reviewing, and Editing. S.M.: Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Reviewing and Editing. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical declaration: Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Obileke, K., Meyer, E.L., Mamphweli, S. et al. Design and evaluation of a gas, temperature profiling and data acquisition system to monitor the performance of a batch fixed dome biogas digester. Sci Rep 14, 24960 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76080-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76080-y