Abstract

To understand the microbial diversity and community composition within the main constructive tree species, Picea crassifolia, Betula platyphylla, and Pinus tabuliformis, in Helan Mountain and their response to changes in soil physicochemical factors, a high throughput sequencing technology was used to analyze the bacterial and fungal diversity and community structure. RDA (Redundancy Analysis) and Pearson correlation analysis were used to explore the influence of soil physicochemical factors on microbial community construction, and co-occurrence network analysis was conducted on the microbial communities. The results showed that the fungal and bacterial diversity was highest in B. platyphylla, and lowest in P. crassifolia. Additionally, the fungal/bacterial richness was greatest in the rhizosphere soils of P. tabuliformis and B. platyphylla. RDA and Pearson correlation analysis revealed that NN (nitrate nitrogen) and AP (available phosphorus) were the main determining factors of the bacterial community, while NN and SOC (soil water content) were the main determining factors of the fungal community. Pearson correlation analysis between soil physicochemical factors and the alpha diversity of the microbial communities revealed a significant positive correlation between pH and the bacterial and fungal diversity, while SOC, TN (total nitrogen), AP, and AN (available nitrogen) were significantly negatively correlated with the bacterial and fungal diversity. Co-occurrence network analysis revealed that the soil bacterial communities exhibit richer network nodes, edges, greater diversity, and greater network connectivity. Indicating that bacterial communities exhibit more complex and stable interaction patterns in soil. This study reveals the complex interactive relationship between microbial communities and soil physicochemical factors in forest ecosystems. By analyzing the response of rhizosphere microbial communities of major tree species in Helan Mountain to nutrient dynamics and pH changes, we can deepen our understanding of the role of microorganisms in regulating ecosystem functions and provide theoretical basis for soil improvement and ecological restoration strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil microorganisms play a crucial role in the biogeochemical cycle of forest ecosystems1,2. They can promote litter decomposition and humus formation, and inhibit the growth of plant pathogens, and therefore play an irreplaceable role in plant growth and ecosystem stability. Soil bacteria can enhance plant tolerance to biotic and abiotic factors3 and increase the bioavailability of nutrients and plant resistance to pathogens4. Fungi are important decomposers in soil5, and some mycorrhizal fungi form mycorrhizae with plants, providing support for nutrient absorption, disease resistance, and adaptation to adverse environmental conditions for plants6. Hence, research into the diversity and community structure of soil microorganisms can provide a foundation for evaluating whether ecosystems are healthy and stable.

The evolution of soil physicochemical factors and above ground vegetation types can cause changes in soil microbial diversity, community structure, and function7. Research on soil bacterial diversity in Panama and Australia indicated that soil pH is the most significant factor affecting the bacterial diversity and richness, while the fungi are less sensitive to soil pH than bacteria are8. A study was conducted on the geographical distribution of soil fungi at a global scale, and the results revealed that soil factors are the best parameters for predicting the fungal diversity and composition, although different fungal taxa exhibit varied patterns in response to changes in soil and plant parameters9,10. In addition, increasing evidence suggests that vegetation type is a crucial factor affecting soil microbial diversity. Tedersoo11 demonstrated in their study of soil microorganisms in forests in Satakunta, Finland, and Järvselja, Estonia, that soil nutrients and tree species have a direct impact on the diversity of different microbial groups. Concurrently, tree diversity serves as a significant driving force of fungal richness. A study on the rhizosphere microorganisms of semideciduous forests in Poland indicated significant differences in the microbial composition and functional levels of the main tree species, including Alnus glutinosa, Betula platyphylla, and Pinus tabuliformis12. These aforementioned studies further clarify the crucial influence of soil factors and vegetation types on the diversity and community structure of soil microorganisms. Therefore, a deeper understanding of the microbial diversity and their interactions with trees will help improve the management and protection strategies of forest ecosystems.

In 2005, Proulx13 first proposed the concepts of co-occurrence and networks. Network analysis helps to characterize complex relationships between species that cannot be directly observed14,15, and more detailed information can be provided to reveal microbial interactions and their functional correlations with ecosystems16. In recent years, network analysis has been widely applied in the in-depth study of microbial interactions. In addition, the modularity exhibited in microbial networks is also a focus of research. The complexity and diversity of microbial communities can be revealed based on the greedy modularity optimization method17, and key taxa (Connector hubs and Module hubs) in co-occurrence networks can be identified through highly correlated taxonomic groups18,19. These key groups are crucial for maintaining network stability and the functionality of specific ecosystems20. They may play a crucial role in nutrient cycling, energy flow, and biodiversity maintenance21. The loss of key groups may lead to the breakdown of modules and networks22. In summary, co-occurrence network analysis can provide new avenues for understanding microbial community structure and interactions between species.

The Helan Mountains are located at the boundary between temperate grasslands and desert areas in northwest China, with complex vegetation types and a typical vertical distribution pattern23. The main constructive tree species, B. platyphylla, P. crassifolia, and P. tabuliformis in Helan Mountain play irreplaceable roles in maintaining ecological balance, soil and water conservation, and water source conservation Northwest China and the upper reaches of the Yellow River24. Therefore, this study analyzed the microbial community structure of the main constructive tree species in the Helan Mountain, and their relationships with soil physicochemical factors. We also constructed a co-occurrence network of the fungi and bacteria and evaluated their stability, exploring the potential key microbial groups and their interrelationships. The results of this study can provide reference for understanding the diversity of microbial communities in forest ecosystems and their complex relationships with host and soil physicochemical factors. By revealing the response mechanisms of rhizosphere microbial communities of major tree species in Helan Mountain under nutrient dynamics and pH regulation, we can deepen our understanding of microbial regulation of ecosystem functions and provide new directions for microbial based soil improvement and ecological restoration.

Results

The physicochemical factor analysis

The physicochemical factors in the rhizosphere soil are shown in Table 1. The results indicated significant differences in all factors except for available potassium (AK) across the three tree species. The NN in the rhizosphere soil of B. platyphylla (32.59 ± 8.23 mg/kg) was significantly greater than that in other tree species. The SWC in the rhizosphere soil of P. tabuliformis (5.87 ± 0.13%) was significantly lower than that in other tree species. The SOC (8.30 ± 0.20%), AP (12.17 ± 1.44%), TN (0.42 ± 0.01%), and AN (63.24 ± 14.31 mg/kg) in the rhizosphere soil of P. crassifolia were significantly greater than those in P. tabuliformis and B. platyphylla, while the pH (7.15 ± 0.15) was significantly lower than that in P. tabuliformis (8.01 ± 0.02) and B. platyphylla (7.93 ± 0.01).

Analysis on microbial community composition

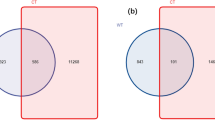

A total of 1410 fungal OTUs (Fig. 1A) and 7059 bacterial OTUs (Fig. 1B) were obtained from the rhizosphere soil of the three constructive tree species. There were 674/4406, 486/3728 and 667/4371 fungal/bacterial OTUs and 433/1266, 267/1044, and 353/933 unique fungal/bacterial OTUs in the rhizosphere soils of B. platyphylla, P. crassifolia, and P. tabuliformis, respectively. B. platyphylla had the greatest number of unique fungal and bacterial OTUs, accounting for 41.12% and 39.04% of all fungal and bacterial OTUs, respectively. The above results indicate that the fungal and bacterial diversities among different forest types are significantly different and that tree species have a remarkable impact on the composition of the bacterial and fungal communities.

The fungal and bacterial OTUs at each classification level were plotted into a string diagram using R software. The results showed that all fungi belonged to 18 phyla, 43 classes, 108 orders, 211 families, and 327 genera (Fig. 2B, D). All bacteria belonged to 26 phyla, 100 classes, 216 orders, 376 families, and 705 genera (Fig. 2A, C). At phylum level, Proteobacteria (32.90%), Actinobacteria (26.50%), Acidobacteria (17.30%), Chloroflexi (9.00%), and Gemmatimonadetes (7.50%) were the dominant bacteria; Basidiomycota (58.70%) and Ascomycota (35.70%) were the dominant fungi. Bacteria and fungi with relative abundances greater than 1.00% and 1.50%, respectively, were defined as dominant genera. Sphingomonas (5.20%), RB41 (4.10%), Bradyrhizobium (2.20%), Variibacter (1.90%), Rhodoplanes (1.30%), H16 (1.10%), Solirubacter (1.20%), and Nocardioides (1.00%) were the dominant bacteria; Sebacina (6.70%), Tomentella (6.50%), Inocybe (6.10%), Geminibasidium (3.70%), Penicillium (2.90%), Archaeorhizomyces (2.80%), Cenococcum (2.60%), Cortinarius (2.50%), Knufia (2.10%), Hebeloma (2.00%), Sarcosphaera (1.70%), Thelephora (1.50%), Sistolema (1.50%), and Agaricus (1.50%) were the dominant fungi.

Differential indicator species analysis

To determine the unique microbial taxa of the main constructive tree species in Helan Mountain, LEfSe analysis was further conducted (Fig. 3). A total of 92/106 fungal/bacterial branches were significantly enriched. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) revealed that there were 44/34, 26/51, and 22/21 fungal/bacterial indicator species for P. crassifolia, B. platyphylla, and P. tabuliformis, respectively. Fungi such as Agaricomycetes, Basidiomycoat, Thelephoraceae and Thelephorales, as well as bacteria such as Acidobacteria and RB41, are enriched in the rhizosphere soil of P. tabuliformis; fungi such as Eurotiomycota and Sortariomycetes, as well as bacteria such as Nitrospira, Nitrospirales, and Gaiellales, are present in the rhizosphere soil of B. platyphylla; fungi such as Gomphaceae and Gomphales, as well as bacteria such as Bradyrhizobiaceae, Bradyrhizobium, and Streptosporangiales, accumulate in the rhizosphere soil of P. crassifolia. The above results indices significantly differed in the composition of the soil microbial communities among different tree species, which also indicates that the host plays an important role in the construction of microbial communities.

The hierarchical relationships of all taxonomic units within the sample communities from phylum to genus. (A) Fungi; (B) Bacteria. The size of each node corresponds to the average relative abundance of the respective taxonomic unit. Different colors represent taxonomic units with significant inter group differences. The letters mark the names of taxonomic units and display significant differences between groups.

Analysis on the microbial diversity

The microbial diversity was evaluated using Simpson and Shannon indices, and microbial richness was assessed with ACE and Chao1 indices (Fig. 4). The results showed that the fungal and bacterial diversity in the rhizosphere soil of B. platyphylla was the highest, while the fungal and bacterial diversity and richness in the rhizosphere soil of P. crassifolia were the lowest. Additionally, the fungal/bacterial richness was greatest in the rhizosphere soils of P. tabuliformis and B. platyphylla respectively. The above results indicate that the host plant significantly affects the diversity and richness of rhizosphere microorganisms.

The PCoA method can be used to demonstrate the differences in microbial composition between different samples. PCoA of the fungal and bacterial communities was conducted using R software based on the unweighted UniFrac distance matrix. The two main axes explained 59.77% of the differences in fungal community composition, with the PC1 axis explaining 34.11% and the PC2 axis explaining 25.66% (Fig. 4J). The two principal coordinates explained 49.45% of the differences in bacterial community composition, with the PC1 axis explaining 32.76% and the PC2 axis explaining 16.69% (Fig. 4I). The intragroup samples of the bacterial and fungal communities in the three tree species were relatively concentrated, while the intergroup samples were relatively dispersed, indicating that tree species play a key role in the construction of soil microbial communities. The microbial communities recruited to the rhizosphere of various tree species may have different ecological functions.

Driving force of soil physicochemical factors on microbial communities

Redundancy analysis was conducted on the soil physicochemical factors and bacterial/ fungal (Fig. 5A, B) genera with relative abundances greater than 1%, and the results showed that AP (33.80%) and NN (29.7%) explained most of the bacterial community structure differences, while NN (38.40%) and SOC (35.80%) explained most of the fungal community structure differences(Table 2). Pearson correlation analysis between the alpha diversity index and soil physicochemical factors (Fig. 5C, D) revealed that pH was significantly positively correlated with the bacterial and fungal diversity, while SOC, TN, AP, and AN were significantly negatively correlated with bacterial and fungal diversity. In addition, TN was significantly positively correlated with SOC and AN; AN was significantly positively correlated with SOC; AP was significantly positively correlated with SOC and TN; and pH was significantly negatively correlated with AN, AP, TN, and SOC.

Co-occurrence network analysis of microbial communities

Co-occurrence network analysis on the fungal and bacterial communities (Fig. 6A, D) revealed that the fungal network consisted of 222 nodes and 440 edges (Fig. 6B), and the bacterial network consisted of 726 nodes and 1349 edges (Fig. 6C). The complexity of the bacterial networks was significantly greater than that of the fungal networks, indicating that bacteria are more abundant and diverse than fungi. Bacteria exhibit more complex interaction patterns in soil, possibly through various relationships such as competition, cooperation, and symbiosis, thereby increasing the complexity of the network. A positive correlation in the network indicates the occurrence of reciprocal interactions, while a negative correlation indicates competition with the host or inhibition between microorganisms. In this study, there were 269 (61.14%) positive correlations and 171 (38.86%) negative correlations in the fungal network. There were 1031 (76.43%) positive correlations and 318 (23.57%) negative correlations in the bacterial network. The bacterial networks exhibited more positive correlations than did the fungal networks, indicating relatively less competition among bacteria.

The modularity index of the fungal network was 0.795, which was greater than 0.40, indicating that the micronetwork had a modular structure (Fig. 6E). There were 5 connector hubs and 1 module hub (Supplementary Table S1), with key taxa including Pochonia, Tomentella, Hebeloma, Cadophora, and an unidentified genus. The highest connectivity centrality value was 8 (Pochonia). In the fungal network, Pochonia was significantly negatively correlated with Penicillium, Malassezia, Inocybe, and Cadophora. Cadophora was significantly negatively correlated with Tomentella and Pochonia.There was a significant positive correlation between Tomentella and Inocybe.

The modularity index of the bacterial network was 0.756 (Fig. 6F), with 7 connector hubs and 7 module hubs (Supplementary Table S2). The key groups at the family level mainly included Acidimicrobiaceae, Nocardioidaceae, Nitrosomonadaceae, Longimicrobiaceae, Bradyrhizobiaceae, and Pseudonocardiaceae. The highest connectivity centrality value was 13 (Nitrosomonadaceae). Nitrosomonadaceae and Bradyrhizobiaceae are nitrogen-fixing bacteria that are significantly positively correlated with Inocybaceae, Gemmatimonadaceae, Subgroup_4, Phylobacteriaceae, Brucellaceae, Caulobacteraceae, and Pseudonocardiaceae, and negatively correlated with Rhizobiaceae. Nocardioidaceae and Pseudonocardiaceae are mostly saprophytic bacteria that are significantly positively correlated with Gemmatimonadaceae, Bradyrizobiaceae, and Brucellaceae and significantly negatively correlated with Hypomonadaceae. Notably, almost all the key fungal groups except Pochonia exhibited significant clustering interactions with OTU358635 (Acidobacteria).

Microbial network and modular analysis of the bacterial and fungal communities. (A,D) Fungi and bacteria; (B,E) Fungi; (C,F) Bacteria. The size of the node is directly proportional to the connectivity of the OTU. The red edge represents positive correlation, and the green edge represents negative correlation.

Discussion

Soil physicochemical properties are the main driving force for structural changes and the spatial distribution of microbial communities. Understanding the relationship between soil and microorganisms is one of the current research hotspots in ecology and soil science. In this study, NN and AP were the main determining factors of bacterial community composition, while NN and SOC were the main determining factors of fungal community composition. It has been reported that AP affects microbial diversity, community composition and function by altering the availability of nitrogen and phosphorus in soil25. Eo et al.26. reported that Sphingomonas and Rhodoplanes decomposed organic phosphorus compounds into inorganic phosphorus by secreting certain enzymes, such as phosphatase27. This could be the reason for the positive correlation between these two genera and AP in this study. Our results showed that SOC has a significant impact on fungal community composition and is positively correlated with ECM fungi such as Cenococcum, Tometella, Hebeloma, and Sebacina. Research has shown that the symbiotic relationship between ECM fungi and plant roots is more stable28 and relatively abundant29 in carbon-rich environments. This is because the carbon provided by plant roots meets the needs of ECM fungi, promoting their growth and reproduction in the soil. In addition, numerous studies have shown that higher soil nitrogen content reduces microbial diversity30,31. Wang et al.32. reported a significant negative correlation between soil nitrogen content and the fungal and bacterial diversity, which may be due to the accumulation of nitrogen causing a decrease in soil pH and microbial carbon source loss33, and leading to a decrease in microbial diversity. The results of this study also support the above conclusion.

Pearson correlation analysis revealed that TN was positively correlated with both AP and AN, and there was also a noticeable positive correlation between AP and AN, reflecting the synergistic utilization or mutual promotion of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus by microorganisms34. The TN and AN in the rhizosphere soil of P. crassifolia were significantly greater than those in B. platyphylla and P. tabuliformis, which may be due to the presence of more nutrient-enriched bacteria, such as Bradyrhizobium and Mesorhizobium, in the rhizosphere soil of P. crassifolia. According to previous reports, these compounds can enhance the nitrogen fixation ability of plants35,36. The NN content in the rhizosphere soil of B. platyphylla was significantly greater than that in P. crassifolia and P. tabuliformis. This may be due to the enrichment of Nitrobacteria in the rhizosphere soil of B. platyphylla, which can oxidize nitrite to nitrate, and enriching NN in soil and promoting the soil nitrogen cycling process37,38.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) shows the bacterial and fungal communities among different tree species are significant different. B. platyphylla has the highest bacterial and fungal diversity, while P. crassifolia has the lowest. This may be due to the different chemical substances secreted by the roots of different tree species, which affect the composition of microbial communities39. Additionally, changes in the amount of aboveground and belowground litter alter the physicochemical properties of the soil, thereby having a significant impact on the microbial community40,41. The differential indicator microorganisms have a profound impact on their nutrient acquisition and adaptability to the environment of their hosts through specific ecological functions. The enrichment of nitrifying bacteria in the rhizosphere of B. platyphylla, such as Nitrospira and Nitrospirales, significantly increases the nitrate nitrogen supply in the soil by promoting nitrogen cycling42. This is particularly crucial for B. platyphylla, which have a high demand for nitrogen. This not only effectively promotes the growth rate and biomass accumulation of B. platyphylla, but also improves its nitrogen utilization efficiency. Subsequently, B. platyphylla occupies an ecological advantage in nitrogen resource competition, thereby enhancing its adaptability and survival competitiveness in different soil environments. The differential indicator microorganisms in P. tabuliformis, such as Acidobacteria and RB41 play important roles in carbon cycling. They maintain the dynamic balance of soil organic carbon by decomposing organic matter, especially in acidic environments. These microorganisms release nutrients needed by plants through decomposition, allowing P. tabuliformis to grow in relatively barren soil43,44. Some members of Gomphaceae and Gomphales in the rhizosphere soil of P. crassifolia form ectomycorrhizae with plants, thereby establishing a close symbiotic relationship with plants and helping P. crassifolia absorb insoluble phosphorus more effectively. This is particularly important for P. crassifolia growing in barren and low phosphorus soil45. In addition, bacteria such as Bradyrhizobium and Streptosporangiales enriched in the rhizosphere of P. crassifolia increase soil nitrogen content through nitrogen fixation, providing a stable source of nutrients for the growth of P. crassifolia, enabling it to maintain efficient growth in arid and barren environments46,47. Overall, these microbial communities enhance the ecological adaptability and competitive advantages of B. platyphylla, P. tabuliformis, and P. crassifolia in their respective ecological niches by providing key nutrients and promoting soil nutrient cycling. Therefore, soil microbial communities provid critical support for the maintenance and stability of forest ecosystems.

In this study, the bacterial communities exhibited richer network nodes, edges, diversity, and greater network connectivity (Fig. 6C), indicating that bacteria exhibited more complex and stable interaction patterns15,48. However, the modularity index and clustering coefficient of the fungal communities were greater than those of the bacterial communities (Fig. 6B), indicating a greater degree of modularity in the fungal communities. Fungi in the community tend to gather together to form subnetworks with relatively independent characteristics and functions rather than being completely randomly interconnected. This difference may be due to the various ecological functions of fungi and bacteria in the soil49. Fungi may exhibit significant diversity in terms of decomposing organic matter, establishing symbiotic relationships with plants, and undertaking other ecological roles, ultimately leading to more specialized interactions and the formation of more modular structures among them. Compared with the fungal communities, the bacterial communities may be more similar in terms of some ecological functions, resulting in a lower level of modularity. A lower level of modularity indicates that cross-module associations between different groups may be more common50. If environmental interference affects some modules, then this impact may spread to other modules17. It is worth mentioning that there are more positive rather than competitive relationships in fungal communities, possibly because these fungi have sufficient resources. Certain soil conditions may be more conducive to supporting synergistic relationships between fungi, such as mutual secretion of beneficial substances, shared use of resources, or collaborative participation in ecosystem functions51.

In addition, we identified several important key nodes in the network, such as Pochonia, Tomentella, Hebeloma, Cadophora, Acidimicrobiaceae, Nocardioidaceae, Nitrosomonadaceae, Longimicrobiaceae, Bradyrhizobiaceae and Pseudonocardiaceae. These nodes play a crucial role in the connection and module structure of the microbial networks, and their loss may lead to the collapse of modules and networks22. Among them, Pochonia has a strong pathogenic effect on soil nematodes52. Tomatella and Hebeloma are ectomycorrhizal fungi that are prone to forming symbiotic relationships with plants, thereby increasing plant uptake of nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium53. Tomentella and Hebeloma are negatively correlated with Cortinarius, Helvella, and Sebacina, possibly because they are all ectomycorrhizal fungi with similar functions, which leads to their competition for ecological niches. Bradyrizobiaceae, Nitrosomonadaceae, and Acidimimicrobiaceae all may promote nitrogen cycling in ecosystems54,55. Pseudonocardiaceae and Nocardioidaceae can participate in the decomposition and cycling of organic matter, thereby promoting vegetation growth56. Cadophora is a potential plant pathogen that can cause wood decay57 and is negatively correlated with Tomentella, suggesting that Tomentella may inhibit or weaken invasion of plants by Cadophora. In addition, Acidobacteria was present in most modules, indicating its dominant role in the soil microbiome. In addition to the key nodes mentioned above, we also identified some low-abundance species in the network. Several previous studies have shown that certain low-abundance species may play a disproportionate role in soils, indicating that some rare species play a crucial role in ecosystems51,58. However, further research is needed to evaluate these rare species.

This study discussed the response patterns of rhizosphere microbial communities within the main tree species in Helan Mountains on key physicochemical factors such as soil nutrient dynamics and pH values. The research results will provide theoretical support for soil regulation and ecosystem functional maintenance. Meanwhile, it can be created conditions for the enrichment of specific microorganisms by optimizing soil nutrient levels (especially nitrogen, phosphorus, and organic carbon content) and adjusting pH values. In addition, this study further revealed the ecological roles of key functional microbial communities in soil by constructing co-occurrence networks, especially some bacterial and fungal groups with potential application value, such as Pochonia and Nitrosomonadaceae, which exhibit significant ecological functions in soil nutrient cycling, pathogen inhibition, and promoting plant growth. This will provide a theoretical basis for the development of microbial inoculants. In the future, theoretical support can be provided for agricultural soil improvement and ecological restoration, and new solutions can be supplied for sustainable agricultural practices, such as reducing fertilizer utilization, improving crop health and productivity, by systematically analyzing the functional characteristics of the microbial communities and their interactions with the plant-soil system.

Methods

Description of the study area and materials

The research area is located in Helan Mountain National Nature Reserve in Inner Mongolia, Northwest China (105°25′~105°28′E, 38°36′~38°40′N), which has typical continental climate characteristics. The reserve has an annual average temperature of 3.1 °C and an annual average precipitation ranging from 268.75 ~ 300.00 mm.

Three repeated sampling sites were set up randomly within the concentrated distribution area of each tree species of B. platyphylla, P. crassifolia, and P. tabuliformis, and each sampling site had a size of 100 m × 100 m and a spacing of 200 m. Within various sampling sites, random sampling was conducted according to the sigmoidal distribution, and 10 healthy plants were selected. During sampling, the surface layer of the dead branches and leaves was first cleared with a shovel and then gently dragged along the roots to the end of the root to collect the rhizosphere soil. The soil collected from each sampling site was mixed evenly, stored in a low-temperature ice box, and quickly returned to the laboratory. The collected soil samples were filtered through a 2 mm soil sieve and divided into two parts. One part was used for high-throughput sequencing (stored at -80 °C), and the other part was used for testing the soil physicochemical properties (partially air-dried and partially frozen).

Analysis of soil physicochemical properties

In this study, various soil physicochemical properties, including SOC (soil organic carbon content), AN (available nitrogen), NN (nitrate nitrogen), TN (total nitrogen), SWC (soil water content), AK (available potassium), AP (available phosphorus), and soil pH, were measured. The determination was carried out using the method of reference Methods of Soil Analysis59.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and Illumina MiSeq sequencing

A PowerSoil® DNA Isolation Kit was used to extract the microbial metagenomic DNA from the soil, the quality of extracted DNA was checked through gel electrophoresis using 1.0% (w/v) agarose. In addition, the concentration of DNA was measured using a NanoDrop NC 2000 spectrophotometer. The V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16SrRNA gene and the highly variable ITS2 region of the fungal ITS gene were selected as target fragments for high-throughput sequencing. The fungal specific primers used were gITS7F (5’-GTGARTCATCGARTCTTTG-3’) and ITS4R (5’-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3’). 338 F (5’-barcode + ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAG- CA-3’) and 806R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’) were used as the bacterial specific primers. The PCR system included Q5 high-fidelity DNA polymerase (0.25 µL), 5× reaction buffer (5.00 µL), 5× high GC buffer (5.00 µL), dNTPs (10 mM) (2.00 µL), template DNA (2.00 µL), forward primer (10 µM) and reverse primer (10 µM) (1.00 µL), with water added to 25 µL. The amplification conditions were as follows: 98 °C for 30 s; 98 °C for 15 s, 50 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s for 26 cycles; and extension at 72 °C for 5 min and storage at 4 °C. The PCR amplification products were separated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the target bands were recovered and purified using the Axygen kit. Libraries were constructed using Illumina’s TruSeqNano DNA LT Library Prep Kit, and library quality was assessed with an Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit and Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit, followed by paired-end sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq v3 platform (2 × 300 bp).

Statistical analyses

The QIIME (Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology, v1.8.0, http://qiime.org/) software was used to identify ambiguous sequences, and USEARCH (v5.2.236, http://www.drive5.com/usearch/) was used to check and eliminate chimeric sequences. The sequences obtained were clustered, and operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were delineated at 97% sequence similarity using the UCLUST sequence alignment tool. Taxonomic information for each OTU was obtained from the Greengenes (Release 13.8, http://greengenes.secondgenome.com/) and UNITE (Release 5.0, https://unite.ut.ee/) databases. OTUs with an abundance lower than 0.001% of the total sequencing volume for all samples were removed, and the resulting abundance matrix was used for a series of subsequent analyses. The analysis of all microbial communities was based on standardized operational taxonomic unit (OTU) tables in R version 4.3.1 (https://www.r-project.org/). The “vegan” and “picante” packages in the R statistical computing environment were used to calculate the alpha diversity indices for the bacteria and fungi (including the Chao1, Shannon, ACE, and Shannon indices), and LEfSe analysis was performed through the Galaxy online analysis platform. The “vegan” package was used to complete the Mantel test, which assesses the correlation or similarity between the data in two matrices. The “ggcor” package was used to create graphical representations of the correlation matrix for visualization. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the bacterial and fungal OTUs was conducted based on unweighted UniFrac dissimilarity. Redundancy analysis (RDA) of the environmental factors and microbial communities was performed using Canoco5 software. The co-occurrence network used the greedy modular optimization method to detect modules58, which were visualized through Gephi software (version 0.10.1, https://gephi.org/). The “igraph” package was used to calculate node topological features, including degree, betweenness, closeness, and eigenvector. Based on the connectivity values within (Zi) and between (Pi) modules, the node attributes of the topological structure were classified into four types: module hubs (Zi > 2.5 and Pi < 0.62), connectors (Zi < 2.5 and Pi > 0.62), network hubs (Zi > 2.5 and Pi > 0.62), and peripherals (Zi < 2.5 and Pi < 0.62). Module hubs, connectors, and network hubs were classified as key nodes.

Data availability

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The raw sequence data supporting the findings of this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number [PRJNA1131174] (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1131174).

References

Djukic, I., Zehetner, F., Mentler, A. & Gerzabek, M. H. J. S. B. Biochemistry. Microbial community composition and activity in different Alpine vegetation zones. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 42, 155–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.10.006 (2010).

Orgiazzi, A. et al. Soil biodiversity and DNA barcodes: opportunities and challenges. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 80, 244–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.10.014 (2015).

Ling, N., Wang, T. & Kuzyakov, Y. Rhizosphere bacteriome structure and functions. Nat. Commun. 13, 836. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28448-9 (2022).

Wei, Z. et al. Trophic network architecture of root-associated bacterial communities determines pathogen invasion and plant health. Nat. Commun. 6, 8413. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9413 (2015).

Oliverio, A. M. et al. The global-scale distributions of soil protists and their contributions to belowground systems. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax8787. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax8787 (2020).

Pang, Z. et al. Soil Metagenomics reveals effects of continuous sugarcane cropping on the structure and functional pathway of Rhizospheric Microbial Community. Front. Microbiol. 12, 627569. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.627569 (2021).

Panico, S. C. et al. Soil biological responses under different vegetation types in Mediterranean Area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020903 (2022).

Ramoneda, J. et al. Building a genome-based understanding of bacterial pH preferences. Sci. Adv. 9 https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adf8998 (2023).

Philippot, L., Chenu, C., Kappler, A., Rillig, M. C. & Fierer, N. The interplay between microbial communities and soil properties. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 22, 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00980-5 (2024).

Tedersoo, L. et al. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 346, 1256688. https://doi.org/10.1126/Science.1256688 (2014).

Tedersoo, L. et al. Tree diversity and species identity effects on soil fungi, protists and animals are context dependent. ISME J. 10, 346–362. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2015.116 (2016).

Gałązka, A. et al. Biodiversity and Metabolic Potential of Bacteria in Bulk Soil from the Peri-root Zone of Black Alder (Alnus glutinosa), Silver Birch (Betula pendula) and scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 2633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23052633 (2022).

Proulx, S. R., Promislow, D. E. & Phillips, P. C. Network thinking in ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20, 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2005.04.004 (2005).

Coyte, K. Z., Schluter, J. & Foster, K. R. The ecology of the microbiome: networks, competition, and stability. Science 350, 663–666. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad2602 (2015).

Hernandez, D. J., David, A. S., Menges, E. S., Searcy, C. A. & Afkhami, M. E. Environmental stress destabilizes microbial networks. ISME J. 15, 1722–1734. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-00882-x (2021).

de Vries, F. T. et al. Soil bacterial networks are less stable under drought than fungal networks. Nat. Commun. 9, 3033. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05516-7 (2018).

Ma, W. et al. Characteristics of the fungal communities and Co-occurrence Networks in Hazelnut Tree Root endospheres and Rhizosphere Soil. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 749871. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.749871 (2021).

Fernandez-Bayo, J. D., Simmons, C. W. & VanderGheynst, J. S. Characterization of digestate microbial community structure following thermophilic anaerobic digestion with varying levels of green and food wastes. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 47, 1031–1044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10295-020-02326-z (2020).

Guimera, R. & Amaral, L. A. N. Cartography of complex networks: modules and universal roles. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. P02001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2005/02/P02001 (2005).

Banerjee, S., Schlaeppi, K. & van der Heijden, M. G. Keystone taxa as drivers of microbiome structure and functioning. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 567–576. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0024-1 (2018).

Bardgett, R. D. & van der Putten, W. H. Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature 515, 505–511. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13855 (2014).

Power, M. E. et al. Challenges in the quest for keystones: identifying keystone species is difficult—but essential to understanding how loss of species will affect ecosystems. BioScience 46, 609–620. https://doi.org/10.2307/1312990 (1996).

Zhang, X. et al. Stochastic processes dominate community assembly of ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with Picea Crassifolia in the Helan Mountains, China. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1061819. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1061819 (2022).

Gauthier, S., Bernier, P., Kuuluvainen, T., Shvidenko, A. Z. & Schepaschenko, D. G. Boreal forest health and global change. Science 349, 819–822. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa9092 (2015).

Chen, X. et al. Long-term continuous cropping affects ecoenzymatic stoichiometry of microbial nutrient acquisition: a case study from a Chinese Mollisol. J. Sci. Food Agric. 101, 6338–6346. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.11304 (2021).

Eo, J. & Park, K. C. Long-term effects of imbalanced fertilization on the composition and diversity of soil bacterial community. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 231, 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.06.039 (2016).

Jager, E. A. et al. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation does not stimulate soil phosphatase activity under temperate and tropical trees. Oecologia 201, 827–840. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-023-05339-4 (2023).

Clemmensen, K. E. et al. Carbon sequestration is related to mycorrhizal fungal community shifts during long-term succession in boreal forests. New. Phytol. 205, 1525–1536. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13208 (2014).

Whalen, E. D. et al. Root control of fungal communities and soil carbon stocks in a temperate forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 161, 108390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2021.108390 (2021).

Dong, H. et al. Change in root-associated fungal communities affects soil enzymatic activities during Pinus massoniana forest development in subtropical China. Ecol. Manag 482, 118817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118817 (2021).

Koizumi, T., Hattori, M. & Nara, K. Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities in alpine relict forests of Pinus pumila on Mt. Norikura Japan Mycorrhiza 28, 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-017-0817-5 (2018).

Wang, J., Gao, J., Zhang, H. & Tang, M. Changes in Rhizosphere Soil Fungal communities of Pinus tabuliformis plantations at different development stages on the Loess Plateau. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 6753. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23126753 (2022).

Mao, Q. et al. Effects of long-term nitrogen and phosphorus additions on soil acidification in an N-rich tropical forest. Geoderma 285, 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.09.017 (2017).

Chen, F. S. et al. Nitrogen and phosphorus additions alter nutrient dynamics but not resorption efficiencies of Chinese fir leaves and twigs differing in age. Tree Physiol. 35, 1106–1117. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpv076 (2015).

Tao, J., Wang, S., Liao, T. & Luo, H. Evolutionary origin and ecological implication of a unique Nif island in free-living Bradyrhizobium lineages. ISME J. 15, 3195–3206. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-021-01002-z (2021).

Zhou, D. et al. Mesorhizobium huakuii HtpG Interaction with nsLTP Ais2requiredquired for Symbiotic Nitfixationxation. Plant. Physiol. 180, 509–528. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.18.00336 (2019).

Sepp, S. K. et al. Global diversity and distribution of nitrogen-fixing bacteria in the soil. Front. Plant. Sci. 14, 1100235. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1100235 (2023).

Wendeborn, S. J. A. C. I. E. The chemistry, biology, and modulation of ammonium nitrification in soil. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 2182–2202. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201903014 (2020).

Bais, H. P., Weir, T. L., Perry, L. G., Gilroy, S. & Vivanco, J. M. J. A. R. P. B. The role of root exudates in rhizosphere interactions with plants and other organisms. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 57, 233–266. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105159 (2006).

Moll, J. et al. Resource type and availability regulate fungal communities along arable soil profiles. Microb. Ecol. 70, 390–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-015-

Wardle, D. A. et al. Ecological linkages between aboveground and belowground biota. Science 304, 1629–1633. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1094875 (2004).

Mundinger., A. B. et al. Cultivation and Transcriptional Analysis of a Canonical Nitrospira under stable growth conditions. Front. Microbiol. 26, 1325. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01325 (2019).

Jing, H., Wang, H., Wang, G., Liu, G. & Cheng, Y. Hierarchical traits of rhizosphere soil microbial community and carbon metabolites of different diameter roots of Pinus tabuliformis under nitrogen addition. Carbon Res. 2, 47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44246-023-00081-1 (2023).

Kalam, S. et al. Recent understanding of soil Acidobacteria and their ecological significance: A critical review. Front. Microbiol, 11, 580024. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.580024 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12162913 (2023).

Liu, Y., Li, X. & Kou, Y. Ectomycorrhizal Fungi: participation in nutrient turnover and Community Assembly Pattern in Forest ecosystems. Forests 11, 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11040453 (2020).

Wongdee, J., Boonkerd, N., Teaumroong, N., Tittabutr, P. & Giraud, E. Regulation of Nitrogen fixation in Bradyrhizobium sp. Strain DOA9 involves two distinct NifA Regulatory proteins that are functionally redundant during symbiosis but not during free-living growth. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1644. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01644 (2018).

Paudel, D. et al. Characterization, and Complete Genome sequence of a Bradyrhizobium strain Lb8 from nodules of Peanut utilizing Crack Entry infection. Front. Microbiol. 11, 93. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00093 (2020).

Guseva, K. et al. From diversity to complexity: Microbial networks in soils. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 169, 108604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2022.108604 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Ecological stability of microbial communities in Lake Donghu regulated by keystone taxa. Ecol. Ind. 136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.108695 (2022).

Wu, J., Jiao, L., Qin, H., Che, X. & Zhu, X. Spatial characteristics of nutrient allocation for Picea Crassifolia in soil and plants on the eastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. BMC Plant. Biol. 23, 199. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-023-04214-x (2023).

Feng, K. et al. Biodiversity and species competition regulate the resilience of microbial biofilm community. Mol. Ecol. 26, 6170–6182. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.14356 (2017).

de Gouveia, S. Inoculation of Pochonia chlamydosporia triggers a defense response in tomato roots, affecting parasitism by Meloidogyne Javanica. Microbiol. Res. 266, 127242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2022.127242 (2023).

Cui, J., Bai, L., Liu, X., Jie, W. & Cai, B. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in the rhizosphere of a continuous cropping soybean system at the seedling stage. Braz J. Microbiol. 49, 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjm.2017.03.017 (2018).

Arp, D. J., Stein, L. Y. J. C. R., i., B. & Biology, M. Metabolism of inorganic N compounds by ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38, 471–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409230390267446 (2003).

Wasai-Hara, S. et al. Bradyrhizobium ottawaense efficiently reduces nitrous oxide through high nosZ gene expression. Sci. Rep. 13, 18862. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46019-w (2023).

Crawford, D. L., Pometto, I. I. I., Crawford, A. L., Microbiology, E. & R. L. J. A. & Lignin degradation by Streptomyces viridosporus: isolation and characterization of a new polymeric lignin degradation intermediate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45, 898–904. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.45.3.898-904.1983 (1983).

Travadon, R. et al. Cadophora species associated with wood-decay of grapevine in North America. Fungal Biol. 119, 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funbio.2014.11.002 (2015).

Deng, Y. et al. Network succession reveals the importance of competition in response to emulsified vegetable oil amendment for uranium bioremediation. Environ. Microbiol. 8, 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.12981 (2016).

Sparks, D. L., Page, A. L., Helmke, P. A. & Loeppert, R. H. Methods of soil Analysis, part 3: Chemical MethodsVol. 14 (Wiley, 2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Yun Su from the Helan Mountain National Nature Reserve (HLS) for help during sampling.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y. Z. Y. conceived the experiment. Y. L., K. H. and Y. J. Z. conducted the experiments. Y. Z. Y., M.L. and Y. J. F. analyzed the results. Y. Z. Y. wrote the manuscript. Y. Z. Y. and M. L. reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Li, Y., Hao, K. et al. Microbial community composition and co-occurrence network analysis of the rhizosphere soil of the main constructive tree species in Helan Mountain of Northwest China. Sci Rep 14, 24557 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76195-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76195-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Influence of salt-tolerant medicinal herbs on soil geochemistry, nutrient cycling, and microbial communities in saline–alkali ecosystems of inner Mongolia

Environmental Geochemistry and Health (2026)

-

Genomic insights into phenol degradation by halophilic bacteria and their potential application in saline soil remediation

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Optimized the ratio of super absorbent polymer and bio-fertilizer for better ecological rehabilitation in Bayan Obo mine, China

Discover Sustainability (2025)