Abstract

The significance of health literacy for elderly individuals with chronic illnesses lies in managing and delaying disease development, which is affected by personal and environmental factors. Family communication can provide an emotional support environment; self-efficacy is an important factor of subjective initiative and personality. A relatively persistent thinking and behavior pattern can affect the environment, subjective initiative, and individual health outcomes. This study aims to explore the effects of the Big Five personality traits on the health literacy of elderly individuals with chronic illnesses and to hypothesize that family communication and self-efficacy mediate the Big Five personalities and health literacy. A cross-sectional study of 2251 elderly individuals with chronic diseases was conducted through nationwide random quota sampling. The structural equation model was used to explore the mediating role of family communication and self-efficacy between the Big Five personality and health literacy. Family communication played a simple mediating role in the influence of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism on health literacy. Self-efficacy played a simple mediating role in the influence of the Big Five personalities on health literacy. Self-efficacy and family communication played a chain mediating role between extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and health literacy. Nurses can enhance the health literacy of elderly individuals with chronic illnesses with extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism through family communication and self-efficacy while promoting the health literacy of those with openness through self-efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to declining fertility rates and longer life expectancy, many countries face unprecedented rapid growth in elderly individuals1; China is the fastest-aging country with the largest elderly population globally2. The latest 2020 Census results estimated that 18.7% of the population is over 603, profoundly affecting the healthcare system and economic development4. Population aging contributes to increased chronic disease prevalence; this prevalence is increasing globally and is causing approximately 41 million (71%) deaths yearly5. The chronic disease prevalence in elderly patients is the highest6. As a vulnerable group, elderly patients with chronic diseases have a large health gap with others.

Health literacy is the capacity of individuals to obtain, handle, and comprehend essential health information and services needed to make adequate health decisions: basic functions (i.e., literacy and numeracy), interactivity (i.e., patient willingness to form co-building partnerships with healthcare providers), and key skills (i.e., patient’s ability to differentiate between available health services). These are necessary to function properly in the healthcare delivery system7,8,9. Health literacy predicts individual health better than age, income, education level, and race10. It is a critical factor for achieving health outcomes and quality of life for people with chronic illnesses11.

The “Healthy China 2030 Plan,” launched in 2016, emphasizes the need to enhance the national health literacy of the whole population, especially to strengthen the intervention and management of key groups such as elderly individuals with chronic diseases. Health literacy gaps significantly affect disparities in health behaviors and outcomes. Individuals with low health literacy may deliberately avoid disease-related information due to fear of disease, distrust of medical staff, and poor initiative in seeking health information12,13,14. Furthermore, people with low health literacy are more inclined to cancer fatalism, believing that cancer outcomes are determined by fate, affecting active screening and treatment compliance15,16. The progressive development of chronic diseases in the elderly population will also cause cognitive and emotional disorders, further hindering their access to and understanding of health information17. Patients with low or insufficient health literacy lacking health-related cognition and understanding ability may be unable to access health information effectively and interact with medical professionals. It makes controlling chronic diseases difficult and causes poor health outcomes18,19, affecting elderly individual mortality: Elderly often have poor perceptions of health status, delayed diagnosis, lower adherence to treatment, and misuse of health care resources, escalating health care costs9,18,20. Therefore, improving the health literacy of elderly individuals with chronic illnesses can reduce disease-related risk factors, delay disease occurrence and development, and improve the effective utilization of medical and health resources21.

Personality can reflect the individual tendency to respond in a given situation22, making individuals with different personalities have different social relationships, affecting their health-related behaviors and outcomes: compliance with the medical system, the success of treatment, and health status and mortality risk24. The Big Five personality model–including agreeableness, neuroticism, extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness–is the most influential and widely accepted personality theory used to explore the link between personality and health. Extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness and conscientiousness describes interpersonal interaction degree, the quality of interpersonal orientation, emotional stability, the willingness to accept new ideas and goal-oriented motivation, respectively24. Recently, the relationship between the Big Five personality and health literacy has been reported, and a Japanese study found that the health literacy of older people is negatively correlated to neuroticism and positively correlated with openness, a sense of conscientiousness, and extraversion25. Interpersonal factors also impact the eHealth literacy of elderly individuals26; family relationships (the most important relationship among elderly individuals) are an integral part of social networks and cultural identity that maintain and promote e-Health literacy among elderly individuals27,28. As the core figure of family chronic disease management and health promotion, the subjective initiative of elderly individuals with chronic illnesses is extremely important; self-efficacy is an important factor of subjective initiative that can evaluate and improve chronic disease prevention and self-management29,30,31. Family support can improve the self-efficacy of older people in the community, directly or indirectly affecting healthy aging through health-promoting behaviors31. To further clarify the influencing mechanism of personality traits on health literacy in elderly patients with chronic diseases, this study used reciprocal determinism in social cognitive theory. In this theory, individual behavior is determined by the interaction of personal attributes, social and family environment, and behavior32. For example, individual beliefs and thinking styles will change the influence of the environment on their behavior. However, it does not mean the interactions have the same strength or occur simultaneously33. Such interactions go beyond the common notion that the person or the environment directly determines behavior, and we can promote health-related behavior by understanding and intervening among these aspects.

Personality traits describe individual internal qualities and are relatively stable34; interventions targeting personality may not necessarily affect health outcomes24. However, in triadic reciprocal causality, individuals are both the product and the influencer of their environment33. Therefore, this study uses family communication and self-efficacy as mediating variables to explore the mechanism and ways of personality on health literacy of elderly individuals with chronic illnesses to further understand the explicit behavior of internal personality characteristics of elderly individuals with chronic illnesses35, which is helpful for health professionals to identify risk groups and take targeted intervention measures to enhance the health literacy of elderly individuals with chronic illnesses.

Theory and hypotheses

Relationship between big five personalities and health literacy

Personality is described as comparatively persistent modes of thoughts, emotion, and behaviors that are biologically grounded and develop within family and cultural contexts22, guiding individuals toward specific life paths that produce long-term health outcomes23. The American Institute of Medicine report calls for patient-centeredness in the healthcare system, emphasizing attention to the patient’s thinking and behavior patterns to better meet their needs. The Big Five personality trait is a simple and reliable potential source of individual differences in healthy development22,36. Neuroticism is significantly negatively correlated to health literacy, and neurotic individuals are prone to emotions such as anxiety and fear37, resulting in persistent psychological distress; this will affect health status physiologically and lead to poor health behaviors such as reduced compliance38. Moreover, health literacy knowledge is partly transmitted through social media, and neurotic individuals are more sensitive and socially isolated and may lack communication and support related to health literacy, lowering the health literacy level39. Extroversion, openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness were positively correlated to health literacy, individuals with higher conscientiousness having positive health behaviors and were likely to adhere to treatment protocols and work toward health goals strictly40. Conversely, low conscientiousness meant a lack of self-control and planning38. Individuals with high openness have a higher cognitive level, are sensitive to health information40, and tend to understand and follow medical advice23. The positive attitude inherent in extroversion allows them to accept aging and disease better41, and their sociable characteristics encourage them to participate in social activities and connect with other patients, further increasing disease adaptability38. Agreeableness is characterized by a tendency to trust others, associated with lower morbidity in older adults and good medication adherence in patients with chronic diseases42,43,44.

Mediating effects of family communication

Communication behaviors such as sharing and talking about experiences are important components of successful coping with traumatic events45. Family communication is the interchange of verbal and non-verbal messages between family members46. Effective family communication can help patients understand the trauma caused by the disease, provide them with good family emotional support, and reduce loneliness and other emotional distress to resist the negative events they experience effectively45,47. Different personality traits have different communication characteristics, affecting the perception of family support48. Some personality deficits are also significant factors in low-income family communication. Extroverts have strong social skills, are good at maintaining and strengthening close relationships, and talk to family members about everyday problems. Agreeableness is characterized by altruism and compassion, a large degree of trust in one’s family, a high level of satisfaction with family relationships49, and a greater willingness to communicate one’s thoughts and feelings. Individuals with an open personality may communicate ideas more honestly and value self-expression50. People with high conscientiousness are generally more reliable, can effectively balance family responsibilities with other social roles51, and are more confident in expressing their opinions52, actively caring for family needs, and taking on more responsible roles. Contrary to conscientiousness, neuroticism is characterized by low conscientiousness, lack of social competence, and avoidant personality disorder53. Individuals with higher neuroticism are lonelier39, perceive themselves as difficult to include and accept by others, and lack close relationships and communication with their families.

Moreover, patients with cervical cancer health literacy were found to positively correlate to family communication54. Family-centered networks are viable resources for effectively disseminating health literacy messages and are key to promoting health54. Well-communicated families tend to share health-related information more freely, can communicate openly and effectively about health issues, help create an environment for health literacy development55, and form personal health-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors56. Strong family communication enables family members to provide emotional support to each other and share health-related decision-making processes57. This engagement promotes critical thinking and a deeper understanding of health-related information.

Mediating effects of self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is the perception that an individual believes in their ability to perform the actions needed to achieve a valuable outcome14; it can help the individual work to build and maintain a sense of control over life58. As the basis of social cognitive function adaptation, the Big Five personality is related to self-efficacy in chronic disease management24. Neuroticism, which involves negative self-perception and evaluation, may affect an individual’s ability to achieve desired outcomes and negatively correlates to self-efficacy in healthy behaviors59,60.Extroversion, conscientiousness, and openness individuals tend to regard things as challenges, positively evaluate coping resources61, and have a high sense of self-efficacy.

As an active resource in the fight against disease61, self-efficacy is important in self-management, self-care, and controlling bad behaviors in patients with chronic diseases21; high levels of self-efficacy are assumed to compensate for lacking health literacy20. The higher the self-efficacy of individuals with chronic illnesses, the stronger the awareness of the importance of early diagnosis of diseases and the higher the motivation for treatment compliance and self-management62,63. However, patients with low self-efficacy have a higher sense of helplessness, believing that the disease is random or inevitable and cannot be controlled and changed64. Lack of confidence in action and less likely to involve in decisions related to their health20. Therefore, increasing self-efficacy may help elderly individuals with chronic illnesses to effectively cope with diseases and maintain a high quality of life65, improve their health literacy, and further promote the development of healthy aging31.

Chain mediating effects of family communication and self-efficacy

Family management of chronic diseases is time-consuming and complex, far beyond the general diagnosis and treatment; family-centered empowerment– the ultimate goal of health literacy19–is needed to help families and individuals manage chronic diseases66. Some experts believe that neglecting empowerment makes health literacy difficult to improve. The family-centered empowerment model aims to enhance the ability of the family system to promote the health of their members, positively enhancing the self-efficacy of individuals with chronic illnesses67. Self-efficacy, a central component of social cognitive theory and one of the key concepts of the family-centered empowerment model33,67, is related to personality tendencies and the surrounding environment of disease management in patients with chronic diseases58. Family members can help older people overcome perceived ageism through communication to improve their self-efficacy and use multiple ways to seek scientific health information to improve health literacy26.

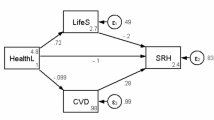

This research aims to identify the relationship between personality traits and health literacy in elderly individuals with chronic illnesses. What is the role of family health and self-efficacy in influencing personality characteristics on health literacy? Given these problems, this study proposes the following hypotheses: Fig. 1 shows the theoretical assumptions.

H1: Different personality traits significantly predict health literacy in elderly individuals with chronic illnesses.

H2: Different personality traits can indirectly predict health literacy in elderly individuals with chronic illnesses through the mediating effect of family communication.

H3: Different personality traits can indirectly predict the health literacy of elderly individuals with chronic illnesses through the mediating effect of self-efficacy.

H4: Different personality traits can indirectly predict the health literacy of elderly individuals with chronic illnesses through the chain mediating effect of family communication and self-efficacy.

Methods

Participants and procedures

“Psychology and Behavior Investigation of Chinese Residents in 2022” was conducted by multistage sampling from June 20 to August 31, 2022. Based on the population pyramid, quota sampling of the selected residents in 148 cities; 202 districts; 390 townships, towns, and streets; and 780 communities and villages from 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan), which was conducted with the quota attributes of sex, age, and urban-rural distribution to obtain the samples68,69. This study was registered in the China Clinical Trial Registry (registration no. ChiCTR2200061046). Ethical approval was granted by Shanxi Institute of International Trade & Commerce (JKWH-2022-02). All participants signed the informed consent documents before participation in this study. All methods were performed following relevant guidelines and regulations. Herein, we selected elderly participants with chronic illnesses.

The inclusion criteria for the study participants were: aged ≥ 60 years with chronic diseases; Chinese; Chinese permanent resident population with an annual travel time of ≤ 1 month; participated voluntarily and filled in the informed consent form; aware of the meaning of each questionnaire item, and completed the questionnaires independently. If the respondent could think but did not have enough action ability to answer the questionnaire, the investigator would conduct a one-to-one interview and then answer the questions on their behalf. The exclusion criteria were individuals with comatose or mental disturbed and those involving in similar research projects. Finally, 2251 residents were enrolled in this study. Figure 2 shows a detailed flowchart of the enrollment.

Assessment instruments

The big five inventory-10 (BFI-10)

The BFI-10 was used to assess personality characteristics on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree), including extraversion (items 1, 6), agreeableness (items 2, 7), conscientiousness (items 3, 8), neuroticism (items 4, 9), and openness (items 5, 10). Items 1, 3, 4, 5, and 7 are reverse-scored. Because only two items were present per dimension in the BFI-10, no Cronbach’s α value was calculated. The BFI-10 scales retain significant levels of reliability and validity70, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of neuroticism, conscientiousness, extraversion, openness, and agreeableness were 0.753, 0.786, 0.723, 0.714, and 0.759, respectively58.

The family communication scale (FCS)

The FCS was used to assess the communication between family members71,72,73; FCS contains ten items and is measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree“74. The summed scores ranged between 10 and 50 points. Higher scores represent better communication between family members. The Cronbach’s α of FCS was 0.956. The FCS is reliable and valid in measuring positive communication in the Chinese population75.

The new general self-efficacy scale–short form (NGSES-SF)

The NGSES-SF is an instrument to assess participants’ belief in their overall competence to perform in various situations, consisting of three parsimonious items in this study, including self-efficacy level, intensity, and universality76. Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), resulting in a score ranging from 3 to 15 points. Higher scores represent greater self-efficacy. The Cronbach’s α for the NGSES-SF was 0.914. NGBES-SF has better reliability and validity than NGSES in studying Chinese residents, which can be applied to research and practice76.

Health literacy scale-short form (HLS-SF)

The HLS-SF was used to measure participants’ health literacy77, consisting of nine items in three dimensions: health care, disease prevention, and health promotion in this study. Each item is scored on a 4-point scale from 0 (very difficult) to 3 (very easy). The summed items have a total score from 0 to 27, with a higher score demonstrating better health literacy. The Cronbach’s α of HLS-SF was 0.917. The HLS-SF is reliable and valid in previous studies of the entire population of six Asian countries77.

Data collection

This study conducts screening and uniform training for investigators to ensure that they are familiar with standardized procedures and criteria for questionnaire filling, and tests are conducted according to the training content, and those who pass the test are assigned regional and specific tasks. In the process of questionnaire distribution, scientific research design principles and statistical requirements are followed to control possible deviations in the data collection process. The collected questionnaires were summarized and evaluated at different stages of questionnaire distribution.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 26.0 were used to analyze the data, and a two-sided p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were performed first. Shapiro-Wilk normality test was used to test the normality of data. Spearman correlation analysis was used to analyze the correlation between variables due to the non-normality of data. SEM analysis and full information likelihood estimation were used to test the hypothesized mediation model, and bootstrap analysis with 5000 replications was used to verify the significance of total effect, direct effect, and total indirect effect. PRODCLIN procedure was used to verify the significance of each indirect effect in the mediation model78. The indicators of good model fit included root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.06, comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker Lewis index (TLI) > 0.9.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of elderly patients with chronic diseases. Of these participants, 50.9% were female, and 49.5% were between 60 and 69 years old; 51.1% of respondents completed only primary school or low, and 82.1% of subjects were married; 55.8% of elderly people with chronic illnesses lived in urban; 33.7% or 30.8% of elderly people with chronic illnesses had two or three children. The 41.0% had a family per capita monthly income of 3001–6000 yuan.

Common method deviation test

Because all variables are used in the questionnaire survey method—all derived from self-reports by the subjects common method deviations may exist. Therefore, the Harman one-way ANOVA was used to test this issue. In all projects, six factors had initial eigenvalues > 1, and the first factor accounted for 38.81% of the total variance, which was < 40% of the critical value79. Consequently, this study had no serious problem of common method bias.

Correlation analysis of big five personality traits, self-efficacy, family communication, and health literacy

The variables had a non-normal distribution; therefore, the Spearman correlation analysis was used. Correlation analysis was conducted using the total scores of Big Five personality traits, self-efficacy, family communication, and health literacy (Table 2). Extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness were positively correlated with health literacy (P < 0.001), while neuroticism was negatively correlated to health literacy (P < 0.001); Extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, and self-efficacy were positively correlated to family communication (P < 0.01). Neuroticism was negatively correlated to family communication (P < 0.001), and Extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness were positively correlated to self-efficacy (P < 0.001). Neuroticism was negatively correlated to self-efficacy (P < 0.001).

SEM analysis of big five personality, family communication, self-efficacy, and health literacy

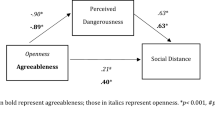

Structural equation modeling was used to test the study hypotheses. The model estimation method was maximum likelihood estimation. The structural equation model was constructed with neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, sense of responsibility, and openness as predictive variables, family communication and self-efficacy as mediating variables, and health literacy as outcome variables. Significance tests were estimated using the bias-corrected bootstrap method and repeated 5000 times after being put back. Through the path coefficient analysis, it was found that openness was not significant for family communication paths. The effects of conscientiousness, agreeableness, and neuroticism on health literacy failed to reach a significant level. Therefore, we adjusted the model to identify the mechanism of action of Big Five personality traits on health literacy (Fig. 3). The results of the adjusted model fit well: χ2 = 79.105, df = 20, RMSEA = 0.036, CFI = 0.993, TLI = 0.983, GFI = 0.993, AGFI = 0.981.

Neuroticism and openness significantly affected health literacy; the effect values were − 0.041 and 0.091. Family communication mediated between extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and health literacy; the mediating effect was 0.057, 0.110, 0.101, and − 0.057, respectively. Self-efficacy mediated between extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, neuroticism, and health literacy, and the mediating effect was 0.019, 0.013, 0.029, 0.008, and − 0.020, respectively. Family communication and self-efficacy mediated between extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and health literacy, and the mediating effect was 0.010, 0.020, 0.018, and − 0.010, respectively. The bias-corrected Bootstrap method was used to verify the significance of the total effect, direct effect, and total mediation effect (Table 3). This study also used MacKinnon’s development and applied the PRODCLIN2 procedure of the product fractional step method to verify the mediation effect of each path separately77(Table 4). If “Extraversion→family communication→self-efficacy” has a mediating effect, and “family communication→self-efficacy→health literacy” also has a mediating effect, it indicates that the chain mediating effect of family communication and self-efficacy exists. The results showed that none of the 95% confidence intervals of the above mediating effects included 0, indicating that the mediating effects were all significant.

Discussion

The results showed that the health literacy level of elderly people with chronic illnesses was significantly correlated to the Big Five personality traits, family communication, and self-efficacy. Neuroticism and openness directly affect health literacy. Family communication mediates the effects of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism on health literacy; self-efficacy mediates the effects of Big Five personalities on health literacy. Extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism can influence health literacy in older patients with chronic diseases through a chain mediating effect of family communication and self-efficacy.

Herein, neuroticism and openness can directly affect the health literacy of elderly people with chronic illnesses. High-level neuroticism inherently has a higher burden of disease42, including persistent psychological distress, increased mental illness, and all-cause mortality37; it is also more likely to have unhealthy eating habits and poor self-management behaviors80,81.Therefore, neuroticism can directly affect health literacy in elderly people with chronic illnesses, consistent with studies on breast cancer survivors and older people in the Japanese community25,82. Openness is closely related to the education level and cognitive function of older people, and older people with a high level of openness are more concerned about their health. They will participate in physical examinations more actively40. Nevertheless, our study failed to find a direct impact of extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness on health literacy in older patients with chronic diseases, which needs further validation.

Family communication mediates the influence of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism on health literacy in elderly people with chronic illnesses. Individuals with high extroversion are flexible and sociable, tend to social encouragement, and are more likely to establish good relationships with other patients38, elicit positive reactions from others, gain trust from others49, and actively seek support to face difficulties–they are successful communicators52. Agreeableness tends to avoid conflict49, understand helping or cooperating with others, and correlate to support levels44,83. Therefore, patients with agreeableness are more likely to get family support and form attachment relationships to meet their desire for a sense of belonging84, increasing patients’ tendency to communicate with family members. Furthermore, the more emotions individuals show in family communication, the easier it is to express their feelings and openly talk about their affairs47. Highly conscientious individuals are often associated with social and environmental factors that promote positive health outcomes, such as higher social status and strong marital relationships85; individuals become more emotionally stable and conscientious with age23. Older people are often committed to collecting health-related information and disseminating it to the younger generation, contributing to family health communication86. Older people with higher openness have higher cognitive behavioral and mental flexibility levels and are not constrained by conservative values43. Openness means more curiosity and willingness to accept new ideas24; they may directly obtain information about diseases through social media25. The influence of family communication on their health status may be lower than their control and cognition of health. Therefore, the effect of openness on family communication in elderly patients with chronic diseases is insignificant. High neurotic individuals are more sensitive and defensive, leading to social inhibition at the cognitive and emotional levels, negatively correlated to willingness to communicate82. Therefore, extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness positively affect family communication in elderly people with chronic illnesses, and neuroticism is a negative predictor of family communication. As the most basic social environment of older people, the family can directly affect the perception of the health status of elderly individuals87; stable family relationships are also predictors of positive health outcomes84. Maintaining close contact with family members leads to more effective conflict resolution and healthier family relationships47, reducing psychological problems and increasing resilience through mutual support47,88. The complexity and uncertainty of the development of chronic diseases bring unpredictable pressure on family members because they cannot rely on previous disease knowledge and coping methods89. Good family communication enables members to absorb new information through discussion and consultation and share their worries and anxiety90, which helps families understand the health changes of elderly people with chronic illnesses and then help them manage and cope with potential disease risks and maintain physical and mental health87. Health communication also transmits information about health management, which is related to life expectancy and the quality of life of family members86. Negative and avoidant family communication affects psychological distress and interpersonal conflicts90, reducing self-esteem and confidence in disease management in elderly patients with chronic diseases91. Therefore, family communication mediated the effects of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism on health literacy.

Our results show that the Big Five personalities can affect the health literacy level of elderly people with chronic illnesses through self-efficacy. Extroverted elderly individuals talk about daily problems with their families, express their thoughts and feelings, and receive more support and help from the outside world92; such positive interactions are an important source of self-efficacy for them31. Additionally, the optimism and external attribution style of extroverted older people help them to be less affected by environmental pressure and have a higher self-efficacy35. Openness individuals are curious and have a high level of cognition40; agreeableness comes from pleasant social behavior and tends to understand and cooperate83. Openness and agreeableness individuals tend to establish strong social relationships23, which can improve their self-efficacy by providing effective support for patients with chronic diseases93. Conscientiousness refers to individuals having a high level of self-control36, being able to effectively adapt and cope with stress, being inclined to follow control norms94, and having high motivation and self-efficacy for successfully achieving health goals38,52. Neurotic individuals are more pessimistic and anxious about their health status23, a negative predictor of self-efficacy in older people41. Low self-efficacy can mediate the effect of neuroticism on depressive symptoms in elderly individuals41. Therefore, the Big Five personality significantly affected self-efficacy, aligning with the previous findings24,41. Self-efficacy, which reflects the perception of the possibility of controlling their lives and achieving goals in people with chronic diseases64, is the most important prerequisite for changing behavior and can influence healthy behaviors through direct or indirect effects95. Chronic disease patients with high self-efficacy have stronger exercise and medication compliance38,64, are more likely to adopt the advice of medical staff, and can more actively seek and use resources to improve their health status and reduce the helplessness caused by disease95. Patients with low self-efficacy have difficulty in effective self-management and more negative emotions, such as anxiety, depression, and learned helplessness96,97. The persistence of such chronic stress reduces resistance to infection and further reduces disease control23. Therefore, elderly patients with chronic diseases who are extraversion, agreeableness, openness, and conscientiousness can increase their health literacy by improving their self-efficacy.

This study found that family communication and self-efficacy mediate between extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism and conscientiousness, and health literacy in elderly people with chronic illnesses. Elderly people with chronic diseases with high extroversion, agreeableness, neuroticism, and conscientiousness can provide positive emotions to family members through positive family communication88. Family members can also understand the disease progress, thoughts, and wishes of the patients by communicating, forming family joint decision-making, and providing corresponding support for them. Self-efficacy, the perceived control of social relationships, is a psychosocial pathway of social support operation that can mediate the effect of support on the physical and mental health of older people. For older people, family members may be extremely important social and emotional resources98,99, and family support has a greater impact on their well-being. Therefore, positive family communication may increase family support for elderly people with chronic illnesses and improve their self-efficacy. Neuroticism is characterized by an avoidant personality53. Under threat, individuals with such avoidant personalities will have stronger negative reactions, and it is not easy to maintain good relationships and interpersonal communication100. Neurotic elderly people with chronic illnesses are threatened by disease progression and poor physical condition. They may be more prone to negative emotions and communication, and pressure cannot be released and responded to, decreasing self-efficacy and poor health literacy. Therefore, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism can affect the health literacy of elderly people with chronic illnesses through the chain-mediating effect of family communication and self-efficacy.

Limitations

This study had certain limitations. First, this is a cross-sectional survey, which cannot explore the causal relationship between the Big Five personality traits and the health literacy of elderly people with chronic illnesses and draw directional conclusions; therefore, longitudinal studies should be used to investigate better the mechanism of change between the Big Five personality traits and health literacy. Second, this study is a large sample multi-center study from China, and the results have certain universality. However, our object was elderly people with chronic illnesses, and there is no classification study and discussion of specific chronic diseases. Future research could be more specific based on the type of chronic diseases and should also consider other confounding factors that affect the health literacy of elderly people with chronic disease. Third, the data collection method was self-report, which is prone to measurement errors due to subjectivity. Subsequently, alternative data collection method, such as multi-angle approaches to collecting personality traits and health literacy of patients with chronic diseases, can be explored to reduce potential response bias from the use of self-reports in this study. Finally, different levels of Big Five personality traits also produce different results, and future research should be based on different degrees of Big Five personality traits.

Conclusions

Individual health literacy differences exist among elderly patients with chronic illnesses with different personality traits. Family communication and self-efficacy positively influence the health literacy of elderly patients with chronic illnesses with extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Therefore, nurses can improve health literacy by paying attention to the communication within the family of elderly patients with chronic diseases with extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and the subjective initiative of patients themselves. Openness can directly or indirectly affect health literacy through self-efficacy. The nurses should help establish and strengthen open in elderly patients with chronic disease control to improve health literacy. Elderly chronic disease patients with higher neuroticism have a lower level of health literacy, which is the focus of the intervention. Neuroticism is directly related to health literacy and affects the health literacy of elderly patients with chronic illnesses through family communication and self-efficacy. Therefore, nurses should pay attention to family communication and emotional support when coping with neurotic elderly patients with chronic diseases, encourage patients to participate actively in chronic disease self-management, reduce negative self-perception and evaluation, and improve their health literacy.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Atella, V. et al. Trends in age-related disease burden and healthcare utilization. Aging Cell. 18 (1), e12861 (2019).

Han, X., Wei, C. & Cao, G. Y. Aging, generational shifts, and energy consumption in urban China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 119 (37), e2210853119 (2022).

Bao, J. et al. Current state of care for the elderly in China in the context of an aging population. Biosci. Trends. 16 (2), 107–118 (2022).

Nguyen, T. N. M., Whitehead, L., Saunders, R. & Dermody, G. Systematic review of perception of barriers and facilitators to chronic disease self-management among older adults: implications for evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 19 (3), 191–200 (2022).

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases[EB/OL]. https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases

Dogra, S. et al. Active aging and Public Health: evidence, implications, and opportunities. Annu. Rev. Public. Health. 43, 439–459 (2022).

Li, H. et al. The Association between Family Health and Frailty with the Mediation Role of Health Literacy and Health Behavior among older adults in China: Nationwide Cross-sectional Study. JMIR Public. Health Surveill. 9, e44486 (2023).

Wang, D., Sun, X., He, F., Liu, C. & Wu, Y. The mediating effect of family health on the relationship between health literacy and mental health: a national cross-sectional survey in China. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 69 (6), 1490–1500 (2023).

Palumbo, R. Examining the impacts of health literacy on healthcare costs. An evidence synthesis. Health Serv. Manage. Res. 30 (4), 197–212 (2017).

Al Sayah, F., Majumdar, S. R., Williams, B., Robertson, S. & Johnson, J. A. Health literacy and health outcomes in diabetes: a systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 28 (3), 444–452 (2013).

Caruso, R. et al. Health literacy in type 2 diabetes patients: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Acta Diabetol. 55 (1), 1–12 (2018).

Loiselle, C. G. Cancer information-seeking preferences linked to distinct patient experiences and differential satisfaction with cancer care. Patient Educ. Couns. 102 (6), 1187–1193 (2019).

McCloud, R. F., Jung, M., Gray, S. W. & Viswanath, K. Class, race and ethnicity and information avoidance among cancer survivors. Br. J. Cancer. 108 (10), 1949–1956 (2013).

Morris, N. S. et al. The association between health literacy and cancer-related attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge. J. Health Commun. 18 (Suppl 1(Suppl 1), 223–241 (2013).

Kobayashi, L. C. & Smith, S. G. Cancer fatalism, literacy, and Cancer Information seeking in the American Public. Health Educ. Behav. 43 (4), 461–470 (2016).

Rodriguez, G. M. et al. Exploring cancer care needs for Latinx adults: a qualitative evaluation. Support Care Cancer. 31 (1), 76 (2022).

Paige, S. R., Flood-Grady, E., Krieger, J. L., Stellefson, M. & Miller, M. D. Measuring health information seeking challenges in chronic disease: a psychometric analysis of a brief scale. Chronic Illn. 17 (2), 151–156 (2021).

Baker, D. W., Wolf, M. S., Feinglass, J. & Thompson, J. A. Health literacy, cognitive abilities, and mortality among elderly persons. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 23 (6), 723–726 (2008).

Jafari, Y., Tehrani, H., Esmaily, H., Shariati, M. & Vahedian-Shahroodi, M. Family-centred empowerment program for health literacy and self-efficacy in family caregivers of patients with multiple sclerosis. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 34 (4), 956–963 (2020).

Papadakos, J. et al. The association of self-efficacy and health literacy to chemotherapy self-management behaviors and health service utilization. Support Care Cancer. 30 (1), 603–613 (2022).

Aliakbari, F., Tavassoli, E., Alipour, F. M. & Sedehi, M. Promoting health literacy and Perceived Self-Efficacy in people with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 27 (4), 331–336 (2022).

Luo, J. et al. Personality and health: disentangling their between-person and within-person relationship in three longitudinal studies. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 122 (3), 493–522 (2022).

Kern, M. L. & Friedman, H. S. Personality and pathways of influence on Physical Health. Soc. Pers. Psycho Comp. 5 (1), 76–87 (2011).

Axelsson, M., Lötvall, J., Cliffordson, C., Lundgren, J. & Brink, E. Self-efficacy and adherence as mediating factors between personality traits and health-related quality of life. Qual. Life Res. 22 (3), 567–575 (2013).

Iwasa, H. & Yoshida, Y. Personality and health literacy among community-dwelling older adults living in Japan. Psychogeriatrics. 20 (6), 824–832 (2020).

Shi, Y., Ma, D., Zhang, J. & Chen, B. In the digital age: a systematic literature review of the e-health literacy and influencing factors among Chinese older adults. Z. Gesundh Wiss. 31 (5), 679–687 (2023).

Alhani, F. et al. The effect of family-centered empowerment model on the quality of life of adults with chronic diseases: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 316, 140–147 (2022).

Francescato, D. et al. Dispositional characteristics, relational well-being and perceived life satisfaction and empowerment of elders. Aging Ment Health. 21 (10), 1052–1057 (2017).

Freund, T., Gensichen, J., Goetz, K., Szecsenyi, J. & Mahler, C. Evaluating self-efficacy for managing chronic disease: psychometric properties of the six-item self-efficacy scale in Germany. J. Eval Clin. Pract. 19 (1), 39–43 (2013).

Lorig, K. R. et al. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med. Care. 39 (11), 1217–1223 (2001).

Wu, F. & Sheng, Y. Social support network, social support, self-efficacy, health-promoting behavior and healthy aging among older adults: a pathway analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 85, 103934 (2019).

Scott, K. et al. Another voice in the crowd: the challenge of changing family planning and child feeding practices through mHealth messaging in rural central India. BMJ Glob Health. 6 (Suppl 5), e005868 (2021).

Chan, X. W. et al. Work–family enrichment and satisfaction: the mediating role of self-efficacy and work–life balance. Intern. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 27 (15), 1755–1776 (2016).

Hayat, A. A., Kohoulat, N., Amini, M. & Faghihi, S. A. A. The predictive role of personality traits on academic performance of medical students: the mediating role of self-efficacy. Med. J. Islam Repub. Iran. 34, 77 (2020).

Rizzuto, D., Mossello, E., Fratiglioni, L., Santoni, G. & Wang, H. X. Personality and survival in older age: the role of Lifestyle behaviors and Health Status. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 25 (12), 1363–1372 (2017).

Israel, S. et al. Translating personality psychology to help personalize preventive medicine for young adult patients. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 106 (3), 484–498 (2014).

Zhang, F. et al. Causal influences of neuroticism on mental health and cardiovascular disease. Hum. Genet. 140 (9), 1267–1281 (2021).

Esmaeilinasab, M. et al. Type II diabetes and personality; a study to explore other psychosomatic aspects of diabetes. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 15, 54 (2016).

Zhou, Y., Li, H., Han, L. & Yin, S. Relationship between big five personality and pathological internet use: Mediating effects of Loneliness and Depression. Front. Psychol. 12, 739981 (2021).

Iwasa, H. et al. Personality and participation in mass health checkups among Japanese community-dwelling elderly. J. Psychosom. Res. 66 (2), 155–159 (2009).

O’Shea, D. M., Dotson, V. M. & Fieo, R. A. Aging perceptions and self-efficacy mediate the association between personality traits and depressive symptoms in older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 32 (12), 1217–1225 (2017).

Chapman, B. P., Roberts, B., Lyness, J. & Duberstein, P. Personality and physician-assessed illness burden in older primary care patients over 4 years. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 21 (8), 737–746 (2013).

Ediger, J. P. et al. Predictors of medication adherence in inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 102 (7), 1417–1426 (2007).

Huver, R. M., Otten, R., de Vries, H. & Engels, R. C. Personality and parenting style in parents of adolescents. J. Adolesc. 33 (3), 395–402 (2010).

Mallinger, J. B., Griggs, J. J. & Shields, C. G. Family communication and mental health after breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl). 15 (4), 355–361 (2006).

Epstein, N. B., Ryan, C. E., Bishop, D. S., Miller, I. W. & Keitner, G. I. The McMaster Model: A view of Healthy Family Functioning (The Guilford Press, 2003).

Haj Hashemi, F., Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F., Oujian, P., Mofid, B. & Bazargan, M. Relationship between perceived social support and psychological hardiness with family communication patterns and quality of life of oncology patients. Nurs. Open. 8 (4), 1704–1711 (2021).

Branje, S. J., van Lieshout, C. F. & van Aken, M. A. Relations between big five personality characteristics and perceived support in adolescents’ families. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 86 (4), 615–628 (2004).

Tov, W., Nai, Z. L. & Lee, H. W. Extraversion and Agreeableness: divergent routes to daily satisfaction with Social relationships. J. Pers. 84 (1), 121–134 (2016).

Smith, S. A., Patmos, A. & Pitts, M. J. Communication and teleworking: a study of communication channel satisfaction, personality, and job satisfaction for teleworking employees. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 55 (1), 44–68 (2018).

Bruck, C. S. & Allen, T. D. The relationship between big five personality traits, negative affectivity, type A behavior, and work–family conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 63 (3), 457–472 (2003).

Sims, C. M. Do the big-five personality traits predict empathic listening and assertive communication? Int. J. list. 31 (3), 163–188 (2017).

Miller, J. D. & Pilkonis, P. A. Neuroticism and affective instability: the same or different? Am. J. Psychiatry. 163 (5), 839–845 (2006).

Zambrana, R. E. et al. Association between Family Communication and Health Literacy among Underserved Racial/Ethnic women. J. Health Care Poor Underserved. 26 (2), 391–405 (2015).

Dutta-Bergman, M. Trusted online sources of health information: differences in demographics, health beliefs, and health-information orientation. J. Med. Internet Res. 5 (3), e21 (2003).

Paasche-Orlow, M. K. & Wolf, M. S. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am. J. Health Behav. 31 (Suppl 1), S19–26 (2007).

Modecki, K. L., Goldberg, R. E., Wisniewski, P. & Orben, A. What is Digital Parenting? A systematic review of Past Measurement and Blueprint for the future. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 17 (6), 1673–1691 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between big five personality and depressive symptoms among Chinese unemployed population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 14, 61 (2014).

Franks, P., Chapman, B., Duberstein, P. & Jerant, A. Five factor model personality factors moderated the effects of an intervention to enhance chronic disease management self-efficacy. Br. J. Health Psychol. 14 (Pt 3), 473–487 (2009).

Williams, P. G., D O’Brien, C. & Colder, C. R. The effects of neuroticism and extraversion on self-assessed health and health-relevant cognition. Pers. Individ Differ. 37 (1), 83–94 (2004).

Ebstrup, J. F., Eplov, L. F., Pisinger, C. & Jørgensen, T. Association between the five factor personality traits and perceived stress: is the effect mediated by general self-efficacy? Anxiety Stress Coping. 24 (4), 407–419 (2011).

Suarilah, I. & Lin, C. C. Factors influencing self-management among Indonesian patients with early-stage chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 31 (5–6), 703–715 (2022).

Tiraki, Z. & Yılmaz, M. Cervical Cancer Knowledge, Self-Efficacy, and health literacy levels of Married Women. J. Cancer Educ. 33 (6), 1270–1278 (2018).

Collado-Mateo, D. et al. Key factors Associated with Adherence to Physical Exercise in patients with chronic diseases and older adults: an Umbrella Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18 (4), 2023 (2021).

Stock, S. et al. A cross-sectional analysis of health literacy: patient- versus family doctor-reported and associations with self-efficacy and chronic disease. BMC Fam Pract. 22 (1), 187 (2021).

Shabany, M., NikbakhtNasrabadi, A., Mohammadi, N. & Pruitt, S. D. Family-centered empowerment process in individuals with spinal cord injury living in Iran: a grounded theory study. Spinal Cord. 58 (2), 174–184 (2020).

Ebrahimi Belil, F., Alhani, F., Ebadi, A. & Kazemnejad, A. Self-efficacy of people with chronic conditions: a qualitative Directed Content Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 7 (11), 411 (2018).

Wu, Y., Fan, S., Liu, D. & Sun, X. Psychological and Behavior Investigation of Chinese residents: concepts, practices, and prospects. Chin. Gen. Pract. J. 27 (25), 3069–3075 (2024).

Yang, Y., Fan, S., Chen, W., & Wu, Y. Broader Open Data Needed in Psychiatry: Practice from the Psychology and Behavior Investigation of Chinese Residents. Alpha Psychiatry. 25 (4):564-565 (2024).

Rammstedt, B. & John, O. P. Measuring personality in one minute or less: a 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. J. Res. Pers. 41 (1), 203–212 (2007).

Akhlaq, A., Malik, N. I. & Khan, N. A. Family communication and family system as the predictors of family satisfaction in adolescents. Sci J Psychol. ; 2013. (2013).

Givertz, M. & Segrin, C. The association between overinvolved parenting and young adults’ self-efficacy, psychological entitlement, and family communication. Commun. Res. 41 (8), 1111–1136 (2014).

Rivadeneira, J. & López, M. A. Family communication scale: validation in Chilean. Acta Colombiana De Psicología. 20 (2), 127–137 (2017).

Olson, D. FACES IV and the Circumplex Model: validation study. J. Marital Fam Ther. 37 (1), 64–80 (2011).

Guo, N. et al. Factor structure and Psychometric properties of the Family Communication Scale in the Chinese Population. Front. Psychol. 12, 736514 (2021).

Wang, F. et al. Reliability and Validity Analysis and Mokken Model of New General Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form (NGSES-SF), 2022).

Duong, T. V. et al. Development and validation of a new short-form health literacy instrument (HLS-SF12) for the General Public in six Asian countries. Health Lit. Res. Pract. 3 (2), e91–e102 (2019).

MacKinnon, D. P., Fritz, M. S., Williams, J. & Lockwood, C. M. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: program PRODCLIN. Behav. Res. Methods. 39 (3), 384–389 (2007).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88 (5), 879–903 (2003).

Novak, J. R. et al. Does Personality Matter in Diabetes Adherence? Exploring the pathways between neuroticism and patient adherence in couples with type 2 diabetes. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being. 9 (2), 207–227 (2017).

Schweren, L. J. S. et al. Diet quality, stress and common mental health problems: a cohort study of 121,008 adults. Clin. Nutr. 40 (3), 901–906 (2021).

Vandraas, K. F., Reinertsen, K. V., Kiserud, C. E., Bøhn, S. K. & Lie, H. C. Health literacy among long-term survivors of breast cancer; exploring associated factors in a nationwide sample. Support Care Cancer. 30 (9), 7587–7596 (2022).

Linkievicz, N. M. et al. Association between Big five personality factors and medication adherence in the elderly. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 44, e20200143 (2022).

Malone, G. P., Pillow, D. R. & Osman, A. The general belongingness scale (GBS): assessing achieved belongingness. Pers. Individ Differ. 52 (3), 311–316 (2012).

Roberts, B. W. & Bogg, T. A longitudinal study of the relationships between conscientiousness and the social-environmental factors and substance-use behaviors that influence health. J. Pers. 72 (2), 325–354 (2004).

Pokharel, M. et al. Health communication roles in latino, Pacific Islander, and caucasian families: a qualitative investigation. J. Genet. Couns. 29 (3), 399–409 (2020).

Kim, S. Y. & Sok, S. R. Relationships among the perceived health status, family support and life satisfaction of older Korean adults. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 18 (4), 325–331 (2012).

High, A. C. & Scharp, K. M. Examining family communication patterns and seeking social support direct and indirect effects through ability and motivation. Hum. Commun. Res. 41 (4), 459–479 (2015).

Clayman, M. L., Galvin, K. M. & Arntson, P. Shared decision making: fertility and pediatric cancers. Cancer Treat. Res. 138, 149–160 (2007).

Geçer, E. & Yıldırım, M. Family Communication and Psychological Distress in the era of COVID-19 pandemic: mediating role of coping. J. Fam Issues. 44 (1), 203–219 (2023).

Lin, M. C. & Giles, H. The dark side of family communication: a communication model of elder abuse and neglect. Int. Psychogeriatr. 25 (8), 1275–1290 (2013).

Mutlu, T., Balbag, Z. & Cemrek, F. The role of self-esteem, locus of control and big five personality traits in predicting hopelessness. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 9, 1788–1792 (2010).

Al-Dwaikat, T. N., Rababah, J. A., Al-Hammouri, M. M. & Chlebowy, D. O. Social Support, Self-Efficacy, and psychological wellbeing of adults with type 2 diabetes. West. J. Nurs. Res. 43 (4), 288–297 (2021).

Bogg, T. & Roberts, B. W. Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: a meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychol. Bull. 130 (6), 887–919 (2004).

Garg, A. et al. Awareness about role of health literacy and self efficacy in tobacco cessation among primary health care workers: a quantitative questionnaire study. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 11 (11), 7036–7041 (2022).

Ge, P. et al. Self-medication in Chinese residents and the related factors of whether or not they would take suggestions from medical staff as an important consideration during self-medication. Front. Public. Health. 22, 10:1074559 (2022).

Smallheer, B. A. & Dietrich, M. S. Social Support, Self-Efficacy, and helplessness following myocardial infarctions. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 42 (3), 246–255 (2019).

Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I. & Seeman, T. E. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 51 (6), 843–857 (2000).

Yang, H., Browning, C. & Thomas, S. Challenges in the provision of community aged care in China. Fam Med. Commun. Health. 1 (2), 32–42 (2013).

Kuster, M. et al. Avoidance orientation and the escalation of negative communication in intimate relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 109 (2), 262–275 (2015).

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.71804125), and Tianjin Medical University Nursing Special Development Fund Project in 2022(2022XKZX-02) (2022XKZX-07).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. J.Q.: Writing – original draft, Validation, Formal analysis. Y.L.: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. X.L.: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. Z.T.: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Y.W.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Project administration. L.C.: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. L.W.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, N., Qi, J., Liu, Y. et al. Relationship between big five personality and health literacy in elderly patients with chronic diseases: the mediating roles of family communication and self-efficacy. Sci Rep 14, 24943 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76623-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76623-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The chain mediating effect of self-efficacy and health literacy between proactive personality and health-promoting behaviors among Chinese college students

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Longitudinal Serial Mediation Relationship of Intolerance of Uncertainty, Irrational Happiness Beliefs and Mistake Rumination with Family Communication

Psychiatric Quarterly (2025)