Abstract

Glaucoma significantly impacts the well-being of millions of people worldwide and contributes to a decline in quality of life. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate quality of life and identify influencing factors among glaucoma patients receiving care at Boru Meda General Hospital in Northeast Ethiopia in 2022. A hospital-based cross-sectional study was conducted at Boru Meda General Hospital from July 10 to September 10, 2022. A total of 432 glaucoma patients were selected through a simple random sampling technique. The participants were interviewed via a structured questionnaire, including the modified Glaucoma Quality of Life-15 tool. The data collected were processed by cleaning, coding, and entering into EPi-data version 4.6 and then analysed via SPSS version 26. Variables with a p value less than 0.05 at the 95% confidence interval were considered statistically significant. A total of 417 participants participated in the study, resulting in a response rate of 96.4%. Among them, 187 individuals, accounting for 44.2% (95% CI 39.8–49.9%), reported having poor quality of life. Factors such as being diagnosed for more than 6 years, residing in rural areas, having other ocular diseases, having bilateral glaucoma, receiving treatment for 1–5 years, experiencing moderate anxiety, and facing moderate depression were significantly associated with poor quality of life, with adjusted odds ratios ranging from 2.555 to 8.035. Approximately half of the participants experienced a diminished quality of life, and significant associations were found with rural residence, time since diagnosis, treatment duration, the presence of other ocular conditions, bilateral glaucoma, and levels of anxiety and depression. The implementation of community-based glaucoma screening initiatives aimed at early identification and treatment, particularly those focused on rural communities and individuals with bilateral glaucoma, is crucial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quality of life (QOL) encompasses various quantifiable aspects of individuals’ lives, such as their physical well-being, personal situations (such as financial status and living conditions), social interactions, daily activities and interests, and broader societal and economic factors1. Personal satisfaction with life is the subjective reaction to these conditions. Comparing an individual or group’s position to that of the entire population can help determine their quality of life (QOL)2.

The chronic and potentially sight-threatening characteristics of glaucoma, along with the irreversible vision loss it causes, are recognized to negatively impact the quality of life (QOL) of patients3. Assessing the extent of vision loss (visual field examination), determining corneal thickness (pachymetry), and evaluating the drainage angle (gonioscopy) are pivotal4.

Early detection of glaucoma is a key priority for glaucoma societies to safeguard visual function and improve patients’ quality of life. Importantly, managing glaucoma should primarily aim to maintain visual function and delay disease progression while also considering the maintenance or improvement of QOL5.

Glaucoma ranks as the second most common cause of preventable blindness following cataracts, accounting for 8% of global blindness cases6. There is a notable correlation between the worsening severity of ocular diseases resulting in visual impairment and a decline in quality of life7. Africa accounts for 15% of the global burden caused by glaucoma. The situation is particularly dire in Sub-Saharan Africa8. Patients with glaucoma experienced a notable decline in their quality of life, with QOL scores worsening as the severity of the disease increased9.

According to the Ethiopian National Blindness and Low Vision Survey, glaucoma is the fifth most common cause of blindness, leading to irreversible vision loss in approximately 62,000 Ethiopians10. The increasing prevalence of glaucoma is anticipated to result in considerable economic challenges and diminished quality of life in Ethiopia11. Research conducted in Gondar revealed that nearly half, or 49.2%, of the participants experienced poor quality of life12.

Glaucoma can impact quality of life through factors such as visual field loss and restricted daily activities, as well as the adverse effects and inconveniences associated with treatments aimed at reducing intraocular pressure13. In the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study (CIGTS), individuals who were younger, female, and had greater comorbidities were found to be more inclined to report a decline in quality of life related to vision14.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that preserving the quality of life of patients has consistently been a primary objective in the management of glaucoma15. Quality of life (QOL) serves as a crucial measure of health and overall well-being, influencing treatment efficacy, resource allocation priorities, and policy formulation16. While early treatment initiation and adherence to prescribed therapy are essential to mitigate the impact of glaucoma on quality of life, Ethiopia faces significant challenges due to delayed diagnosis and inadequate adherence to treatment regimens17. Similarly, quality of life is impacted by various factors, including physical and psychological well-being, degree of independence, social connections, and environmental interactions. These factors can have detrimental effects on quality of life not only for individual patients but also for their families and broader communities18.

Failure to address the disease can result in a decline in patients’ physical capabilities, affecting their ability to engage in everyday tasks such as reading, watching TV, and perceiving objects in their peripheral vision. Additionally, glaucoma patients may face an increased risk of falls and accidents due to these impairments19. Patients experiencing diminished quality of life impose a heavier burden on healthcare resources20. Glaucoma can impact a patient’s quality of life through various means, including psychological impacts such as the emotional toll of diagnosis, concerns about vision loss, fear of passing the condition to family members, and feelings of anxiety and depression21. The visual effects of glaucoma include a decreased visual field and ultimately visual acuity22.

Although few studies have been conducted in Ethiopia on how and to what extent glaucoma influences the QOL of individuals suffering from this disease, many factors that affect quality of life have not been addressed. There are no previous studies performed in this area, and studies performed in other areas may not represent these study areas because there may be environmental, cultural, and economic differences. There is limited information on how the QOL of individuals is affected by glaucoma in Northeast Ethiopia, where resources for both diagnosis and treatment are limited. Furthermore, few studies have examined the interplay between glaucoma severity and its impact on QoL in this region, along with other potential contributing factors, such as sociodemographic characteristics, duration of diagnosis, and the presence of comorbid ocular conditions. This study is the first to comprehensively evaluate the quality of life and associated factors among glaucoma patients at Boru Meda General Hospital in Northeast Ethiopia. This study provides new insights into how local healthcare infrastructure, patient access to care, and socioeconomic conditions uniquely affect QoL in glaucoma patients. The findings will help inform regional healthcare strategies to better support glaucoma patients and identify critical areas for intervention. Understanding the quality of life of glaucoma patients is crucial for tailoring management approaches and improving overall patient care. Given the scarcity of research in Northeast Ethiopia, this study addresses a critical gap by providing context-specific data. The results could guide healthcare providers and policymakers in developing strategies to improve patient outcomes, allocate resources efficiently, and increase awareness of glaucoma’s impact on quality of life in this underresearched setting.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, psychological factors, such as anxiety and depression, are not addressed in Ethiopia; thus, this study aimed to assess the quality of life and associated factors among patients with glaucoma at Boru Meda general hospitals.

Method and materials

Study design, setting, and period

This cross-sectional study was conducted at Boru Meda General Hospital in Dessie town from August to September 2022. Originally, the hospital was established with the primary objective of providing ophthalmology and dermatology services. Owing to the significant number of patients with glaucoma, averaging 752 per month, a study on this topic was initiated.

Study participants and eligibility criteria

The study population comprised all glaucoma patients receiving follow-up care at Boru Meda General Hospital. Eligible participants were individuals aged 18 years above, patients who had been diagnosed with open-angle glaucoma, chronic angle-closure glaucoma, normal tension glaucoma, glaucoma patients who had routinely attended the clinic with regular follow-up, and who were receiving treatment at the hospital during the study period. Those who were newly diagnosed with glaucoma, glaucoma patients who had already been enrolled in the study (including in the pretest), glaucoma patients who were not willing to provide informed written consent, and those with severe illness were excluded from participation.

Sample size determination and sampling techniques

The sample size was calculated via the single population proportion formula, which is based on the prevalence of poor quality of life (49.2%) reported in a previous study conducted at the University of Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. With a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a 5% marginal error, the sample size was determined.

where n = the required sample size; Z = the standard normal deviation at the 95% confidence interval; P = the assumed proportion of patients with poor QOL from glaucoma 49.2% (0.492); and d = the margin of error that can be tolerated, which is 5% (0.05).

Therefore,

When a 10% nonresponse rate was added, the final sample size was 422.

The sample size for the second variable was determined via epi-info version 7.2

Variables | Ratio | Ratio unexposed: exposed | Odds ratio | No unexposed to be studied | No of exposed to be studied | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Rural residence | 1:1 | 0.72 | 1.81 | 166 | 227 | 393 |

Age > 75 | 1:1 | 0.65 | 2.54 | 69 | 105 | 174 |

SeverVisual impartment | 1:1 | 0.76 | 2.02 | 132 | 171 | 303 |

Duration of visual impairment > 3 years | 1:1 | 0.5 | 3.94 | 31 | 61 | 92 |

The sample size calculation was based on a significance level of 5% and a power of 80%. Rural residency was chosen as the exposure variable since it yielded the maximum sample size among the other variables, resulting in 393 participants. Accounting for a 10% nonresponse rate, the final total sample size was determined to be 43212.

Sampling technique and procedures

Glaucoma patients who arrived at the appointment days for follow-up were sent to the ophthalmology department. After the cards were collected from the card room by porters, they were sent to the glaucoma clinic; in the meantime, patients stayed in the waiting room, which was located in front of the secondary eye unit. Once the patients entered the glaucoma clinic, a systematic random sampling method was employed every k unit, which included an average of 1200 glaucoma patients attending the clinic (10 per week), with approximately 30 patients per day from the monthly health management information system report. Among those 10 patients selected via the systematic random sampling method per day within the study period, k = N/n = 1200/432 = 2.77 ≈ 3, in which the first patient was selected via the lottery method after entering the glaucoma clinic and then after every third patient was taken to obtain the sample size in the specified study period.

Operational definitions

Good QOL Individuals who score below the mean on the Glaucoma Quality of Life scale are considered to have a good quality of life23.

Poor QOL Individuals who score greater than or equal to the mean on the Glaucoma Quality of Life scale are considered to have a poor quality of life23.

Nonadherent A person with glaucoma and using antiglaucoma drugs and scoring 3 or more on the 8-item Morisky medication adherence screening tool24.

Glaucoma staging By using a better eye-to-disc ratio (CDR)25, glaucoma staging can be classified as mild (≤ 0.65 DD), moderate (0.7–0.85 CDD) or severe (≥ 0.9 DD)19.

Anxiety Individuals who score a total of less than seven implied noncases (normal), 8–10 for mild cases, 11–14 for moderate cases, and 15–21 for severe cases26.

Depression Individuals who score a total of less than seven implied noncases (normal), 8–10 for mild cases, 11–14 for moderate cases, and 15–21 for severe cases26.

Data collection tools and procedures

Data were gathered through a structured questionnaire that covered sociodemographic details, clinical aspects of glaucoma, and psychological factors. Data collection involved face‒to-face interviews and reviews of patient medical records.

The questionnaire comprises the validated WHO QOL-Brief instrument27 for assessing the outcome variable, along with inquiries on sociodemographic factors and clinical aspects. QOL was evaluated via the WHO-BREF, which has 26 questions focusing on patients’ physical (7 items), social (3 items), psychological (6 items), and environmental (8 items) domains. The score ranged from 1 to 5, where 5 denoted the best perceived QOL by the patient28. With respect to quality of life, the QOL-15 contains 15 items and 4 domains of visual function: central and near vision (2 items), peripheral vision (6 items), glare and dark adaptation (6 items), and outdoor mobility (1 item)29. The QOL-15 has a scoring scale ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 stands for “no difficulty in performing the activity” and 5 for “severe difficulty due to visual reasons”. If patients do not perform a specific activity for reasons other than impaired vision, a score of 0 is given for that task. This can yield a total score between 0 and 75. Poorer QOL-15 scores and increased difficulty with vision-related activities were associated with higher subscale scores30,31.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) score was classified and examined. The HADS is a self-reported 14-item rating scale with a 4-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 to 3). It is designed to measure anxiety and depression (7 items for each subscale). The total score is the sum of the 14 items, and for each subscale, the score is the sum of the respective seven items (ranging from 0–21)32. Scores below 7 were considered noncases (normal), while scores of 8–10 indicated mild cases, 11–14 indicated moderate cases, and 15–21 indicated severe cases33,34. The data collection was conducted by two ophthalmologist nurses and one supervisor.

The WHO classification for visual impairment is based on best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in the better eye and is commonly used in research related to ocular diseases such as glaucoma. Mild or no visual impairment was defined as a presenting distance visual acuity of 6/18 or better. Moderate visual impairment refers to visual acuity that is worse than 6/18 but not worse than 6/60. Severe visual impairment is characterized by visual acuity worse than 6/60 but not worse than 3/60. Blindness is defined as a presenting distance visual acuity of less than 3/6035.

Data quality assurance

To ensure data quality, the questionnaire was first prepared in English and then translated into the local language (“Amharic”) by experts and senior ophthalmologists familiar with the study area. To verify consistency, the final Amharic version was subsequently translated back into English. A two-day training session was conducted for the data collectors and supervisor, covering the questionnaire, ethical conduct, and confidentiality protocols to maintain consistency in data collection. A pretest was conducted on 5% of the sample size at Dessie Specialized Comprehensive Hospital one week prior to the actual data collection. The collected data were reviewed for accuracy, completeness, clarity, and consistency. Daily communication was maintained between the supervisor and data collectors throughout the data collection period. Cronbach’s alpha was computed for the Quality of Life (QOL), Medication Adherence Scale, Anxiety Scale, and Depression Scale to assess the internal consistency of each item, resulting in values of 98%, 74%, and 73%, respectively.

Data processing and analysis

The data collected underwent coding, cleaning, and entry into EpiData version 4.6, after which they were exported to SPSS version 26 for analysis. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations, were utilized to summarize sample characteristics and are presented in tables and graphs. The outcome variable responses were aggregated, and an overall mean was calculated, with subsequent categorization into “good” and “poor” quality of life. Psychological factors were assessed by recording Likert scale responses for each component as normal, mild, moderate, or severe, with scores summed for each participant to obtain an overall score. Hosmer‒Lemeshow goodness of fit was performed to check the model assumption, and multicollinearity was checked to identify the potential confounding variables.

Independent variables with a significance level of p < 0.25 in the bivariate logistic regression were included in the multivariate logistic regression. Variables with a significance level of p < 0.05 at the 95% confidence interval were considered to have a significant association with the quality of life of patients with glaucoma.

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance and approval were secured from the Department of Adult Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, College of Medicine, and Health Sciences, Wollo University. A supportive letter was subsequently provided to the quality unit of Boru Meda General Hospital, and permission was obtained. A letter of permission was subsequently acquired and submitted to the ophthalmic outpatient department (OPD). Prior to participation, the study participants were provided with a detailed explanation of the study’s objectives and significance, and informed written consent was obtained. This study was conducted with the permission and approval of the Wollo University ethical clearance committee with reference number CHMS/07/22. All procedures were conducted in compliance with applicable guidelines and regulations, and the study protocol adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants

The sociodemographic characteristics of the 417 study participants described in Table 1 indicated that most of them were aged 41–70 years (72.7%), male (60.2%), married (65.5%), read and write only (60.0%), farmer (64.5%), rural (70.5%), Muslim (65.5%), and Amhara ethnic (96.4%%). Among the 432 patients who agreed to participate in this study, four hundred seventeen (417) agreed. This number corresponds to a participation rate of 96.4%, with all participants responding to all the questions asked (Table 1).

Clinical and psychological attributes of the study participants

Table 2 below shows that the majority of the participants had a time of diagnosis < 1 year (40.8%), moderate visual impairment (41.2%), bilateral glaucoma (57.6%), stages of glaucoma (50.8%), drug side effects (54.9%), duration of treatment 1–5 years (42.2%), primary open angle glaucoma (89.2%), and no other ocular disease (86.3%) and had either moderate levels of anxiety (44.4%) or moderate levels of depression (48.40%).

Glaucoma-related quality of life of the respondents

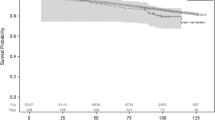

Distribution of overall QOL

In this study, 44.85% (95% CI 39.8–49.9%) of the glaucoma patients had poor quality of life (Fig. 1).

Distribution of the domains of QOL

The GQOL-15 covers four different domains of quality of life: central and near vision, outdoor mobility, peripheral vision, and dark adaptation and glare. In terms of central and near vision, 45.3% (95% CI 40.8–50.1%), outdoor mobility, 42.7% (95% CI 38.4–48.0%), peripheral vision, 47.2% (95% CI 42.4–51.9%) and dark adaptation and glare, 46.5% (95% CI 41.9–51.6%) of the respondents scored above the mean of each subscale poor quality of life (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis

The results of multivariate analysis revealed that quality of life was significantly associated with residence, the time of diagnosis, the duration of treatment, the presence of other ocular diseases, anxiety and depression.

The time of diagnosis was found to be significantly associated with poor quality of life. The respondents whose time of diagnosis was > 6 years was 3.781 years (AOR = 3.781 (95% CI 1.113–11.460)) were 4 times more likely to have poor quality of life than those whose time of diagnosis was less than 1 year.

Patients with other ocular diseases were 5 times more likely to have poorer quality of life than patients with no other ocular diseases were (AOR = 5.172 (95% CI 2.334–11.460)).

With respect to laterality, respondents who had bilateral glaucoma were 8 times more likely to have poor quality of life than were those who currently had unilateral glaucoma (AOR = 8.035; 95% CI 7.944–14.597).

The respondents who had moderate anxiety were 3 times more likely to have poor QOL (AOR = 3.294 (95% CI 1.509–7.194)) than those who had normal anxiety.

With respect to depression, those respondents who had moderate depression were 3 times more likely to have poor QOL (AOR = 2.649 (95% CI 1.067–6.576)) than those who had normal anxiety.

The duration of treatment was found to be significantly associated with poor quality of life. Respondents whose duration of treatment ranged from 1 to 5 years (AOR = 2.555 (95% CI 1.210–5.397)) were 3 times more likely to have poor quality of life than those whose duration of treatment was less than 1 year.

Compared with urban residents, rural residents were 4 times more likely to have poorer quality of life (AOR = 3.832 (95% CI 2.070–7.092)) (Table 4).

Discussion

This study assessed the QOL of glaucoma patients who sought care at Borumeda General Hospital and its associated factors. Overall, the proportion of patients with poor quality of life in this study was 44.85% (95% CI 39.8–49.9%). This result was similar to those of two studies performed by Gondar (49.2% CI 44.2–53.3%)12 and 46.3% CI 28.8–63.8)12,19. This result was higher than those reported in studies conducted in Ibadan (41.4%) and Nigeria (41.35%)36,37. This might be due to the small sample size of patients with glaucoma and the different tools used. Additional reasons for this variation might be differences in lifestyles, economic status, health care systems, professional experience and cultural value.

However, the results of this study were lower than those of other studies performed in Kenya, Gaza and Brazil (83.5%, 59.5%, and 58.8%, respectively)25,29,38,39. This might be due to the instrument they used to assess QOL, which was a time trade-off utility measure.

The time of diagnosis was found to be significantly associated with poor quality of life. The findings of this study are in line with those of other studies performed in Korea and Gondar, Ethiopia19,40.

In this study, patients who received treatments for durations ranging from 1 to 5 years were more likely to have poor quality of life than patients who received treatments for durations of less than 1 year were. This could be because drug expenses and intensive and lifelong follow-up might affect their social interaction and overall quality of life.

Patients with other ocular diseases have poorer quality of life than patients with no other ocular diseases. If patients develop other eye diseases, medical expenses, such as treatment- and investigation-related costs, increase, which is a double burden for patients and has a direct impact on quality of life.

The presence of bilateral glaucoma significantly impacts the quality of life of affected individuals. Compared with unilateral glaucoma, bilateral glaucoma often leads to more severe visual impairment, affecting both eyes and thereby diminishing overall visual function. This can result in a range of challenges, including difficulties with daily activities such as reading, driving, and recognizing faces. Additionally, bilateral glaucoma can contribute to increased levels of anxiety and depression, as individuals may fear further vision loss and the potential impact on their independence and overall well-being. Furthermore, the need for ongoing treatment and management of bilateral glaucoma can place a considerable burden on patients, both financially and emotionally. Overall, the presence of bilateral glaucoma can significantly reduce quality of life and may require comprehensive support and management strategies to address its impact effectively.

Anxiety was associated with the psychological factor of QOL. Moderate levels of anxiety were associated with the participants in this study, a finding that was similar to that of Ghana, Shanghai, China41. Anxiety is associated with QOL; as anxiety rates decrease, QOL improves, and anxiety rates increase.

Depression was associated with quality of life in patients with glaucoma in this study. Thus, increased levels of depression decrease QOL. These findings support the findings of Shanghai, China42, who reported that patients free from depression or minimal depression had higher QOL scores.

In this study, patients who lived in rural areas were four times more likely to have poor quality of life than urban patients were. This may be because glaucoma patients who live in rural areas may not seek medical attention for early detection and diagnosis and may seek care very late after they have advanced into glaucoma stages; this study is similar to that of Kenya and Nigeria36,39. Moreover, individuals residing in rural regions may experience delayed diagnosis of the condition, leading to more advanced visual impairment. Additionally, many rural inhabitants face financial challenges, making it difficult for them to cover transportation and treatment costs.

This study has several limitations. First, the study design was cross-sectional, and the associations between QOL and several variables may not be causal. Second, the VI classification in this study was based on only presenting the distance VA, and other aspects of visual functioning, e.g., contrast sensitivity, visual field, colour vision and stereoacuity, were not assessed. This study did not assess qualitative information from patients, and variables such as comorbidities, intraocular pressure, family support, monthly income and distance from health institutions were not assessed.

Implications and contributions to the field

This research offers significant insights into a region that has received limited attention in glaucoma studies. Like many African nations, Ethiopia is experiencing an increasing incidence of glaucoma, which negatively affects patients’ overall quality of life. However, few studies have focused on the comprehensive quality of life experienced by individuals with glaucoma in this area. By addressing this gap, this study provides valuable data that can inform healthcare policies and initiatives. Specifically, this study highlights the unique challenges faced by Ethiopian patients and the profound impact of advanced-stage glaucoma on their quality of life. Furthermore, the findings offer valuable insights for the development of targeted interventions aimed at improving the quality of life of glaucoma patients. Additionally, by highlighting the difficulties patients face in managing medication regimens, this study underscores the importance of adopting patient-centered care approaches and advocating for greater awareness and support for individuals living with glaucoma.

Overall, the article significantly enhances medical knowledge by offering insights into the quality of life among glaucoma patients in a region that has been overlooked in previous studies. These data can serve as a foundation for healthcare practices, the creation of interventions, and future research endeavors, all aimed at enhancing health outcomes for individuals with glaucoma in Ethiopia.

Conclusions

The findings of this study revealed that the overall quality of life of patients with glaucoma was poor. The quality of life of patients with glaucoma was significantly associated with living in rural areas, the time of diagnosis, the presence of other ocular diseases, and the presence of laterality, anxiety and depression. Educating the glaucoma population on the nature of the disease, advice on early presentation, and better coping strategies for the condition are warranted.

Data availability

All required materials are included in the manuscript. The datasets produced and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly accessible to safeguard against potential misuse of participants’ full data. However, they can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ARMD:

-

Age-related macular degeneration

- CACG:

-

Chronic angle closure glaucoma

- CD:

-

Cup-to-disk ratio

- DD:

-

Disc diameter

- GQOL-15:

-

Glaucoma quality of life-15

- VA:

-

Visual acuity

- VF:

-

Visual field

- VI:

-

Visual impairment

- VRQOL:

-

Vision-related quality of life

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Runjić, T., Novak Lauš, K. & Vatavuk, Z. Effect of different visual impairment levels on the quality of life in glaucoma patients. Acta Clin. Croatica 57(2), 243–249 (2018).

Lee, S. S. Y. & Mackey, D. A. Glaucoma–risk factors and current challenges in the diagnosis of a leading cause of visual impairment. Maturitas (2022).

Quaranta, L. et al. Quality of life in glaucoma: A review of the literature. Adv. Therapy 33(6), 959–981 (2016).

Addepalli, U. K., Jonnadula, G. B., Garudadri, C. S., Khanna, R. C. & Papas, E. B. Prevalence of primary glaucoma as diagnosed by study optometrists of LV Prasad Eye Institute—Glaucoma epidemiology and molecular genetics study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 26(3), 150–154 (2019).

Enoch, J. et al. How do different lighting conditions affect the vision and quality of life of people with glaucoma? A systematic review. Eye 34(1), 138–154 (2020).

Steinmetz, J. D. et al. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: The right to sight: An analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet Glob. Health 9(2), e144–e60 (2021).

Pelčić, G., Perić, N. & Pelčić, G. The importance of the assessment of quality of life in glaucoma patients. Jahr Europski časopis Za Bioetiku 8(1), 73–82 (2017).

Nansseu, J. R. N. & Bigna, J. J. R. Antiretroviral therapy related adverse effects: Can sub-Saharan Africa cope with the new “test and treat” policy of the World Health Organization?. Infect. Dis. Poverty 6(1), 1–5 (2017).

Kyari, F. et al. A population-based survey of the prevalence and types of glaucoma in Nigeria: Results from the Nigeria national blindness and visual impairment survey. BMC Ophthalmol. 15(1), 1–15 (2015).

Belay, D. B., Derseh, M., Damtie, D., Shiferaw, Y. A. & Adigeh, S. C. Longitudinal analysis of intraocular pressure and its associated risk factors for glaucoma patients using bayesian linear mixed model: A data from Felege Hiwot Hospital, Ethiopia. Sci. Afr. 16, e01160 (2022).

Uchino, M. & Schaumberg, D. A. Dry eye disease: Impact on quality of life and vision. Curr. Ophthalmol. Rep. 1, 51–57 (2013).

Yibekal, B. T., Alemu, D. S., Anbesse, D. H., Alemayehu, A. M. & Alimaw, Y. A. Vision-related quality of life among adult patients with visual impairment at University of Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. J. Ophthalmol. 2020 (2020).

Riva, I. et al. Influence of sociodemographic factors on disease characteristics and vision-related quality of life in primary open-angle glaucoma patients: The Italian primary Open Angle Glaucoma study (IPOAGS). J. Glaucoma 27(9), 776–784 (2018).

King, A. J. et al. Baseline characteristics of participants in the treatment of advanced glaucoma study: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 213, 186–194 (2020).

Montana, C. L. & Bhorade, A. M. Glaucoma and quality of life: Fall and driving risk. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 29(2), 135–140 (2018).

Murdoch, I., Smith, A. F., Baker, H., Shilio, B. & Dhalla, K. The cost and quality of life impact of glaucoma in Tanzania: An observational study. PLoS ONE 15(6), e0232796 (2020).

Assem, A. S., Fekadu, S. A., Yigzaw, A. A., Nigussie, Z. M. & Achamyeleh, A. A. Level of glaucoma drug adherence and its associated factors among adult glaucoma patients attending Felege Hiwot specialized hospital, Bahir Dar City, Northwest Ethiopia. Clin. Optometry. 12, 189 (2020).

Pezzullo, L., Streatfeild, J., Simkiss, P. & Shickle, D. The economic impact of sight loss and blindness in the UK adult population. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18(1), 1–13 (2018).

Ayele, F. A. et al. The impact of glaucoma on quality of life in Ethiopia: A case–control study. BMC Ophthalmol. 17(1), 1–9 (2017).

McDonald, M., Patel, D. A., Keith, M. S. & Snedecor, S. J. Economic and humanistic burden of dry eye disease in Europe, North America, and Asia: A systematic literature review. Ocul. Surf. 14(2), 144–167 (2016).

Kalyani, V., Dayal, A., Chelerkar, V., Deshpande, M. & Chakma, A. Assessment of psychosocial impact of primary glaucoma and its effect on quality of life of patients in Western India. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 68(11), 2435 (2020).

Grisafe, I. I. D. J. et al. Impact of visual field loss on vision-specific quality of life in African americans: The African American eye disease study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 229, 52–62 (2021).

Anbesse, D. H. & Gessesse, W. Knowledge and practice towards glaucoma among glaucoma patients at University of Gondar Tertiary Eye Care and Training Center. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 32(5), 2913–2919 (2022).

Moon, S. J., Lee, W-Y., Hwang, J. S., Hong, Y. P. & Morisky, D. E. Accuracy of a screening tool for medication adherence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8. PLoS ONE 12(11), e0187139 (2017).

Machado, L. F. et al. Factors associated with vision-related quality of life in Brazilian patients with glaucoma. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 82, 463–470 (2019).

Michopoulos, I. et al. Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS): Validation in a Greek general hospital sample. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 7, 1–5 (2008).

Ayele, F. A. et al. The impact of glaucoma on quality of life in Ethiopia: A case–control study. BMC Ophthalmol. 17, 1–9 (2017).

Vahedi, S. World Health Organization quality-of-life scale (WHOQOL-BREF): Analyses of their item response theory properties based on the graded responses model. Iran. J. Psychiatry 5(4), 140–153 (2010).

Mushtaha, M. Z. & Eljedi, A. Quality of life among patients with Glaucoma in Gaza governorates. IUG J. Nat. Stud. 28(1) (2020).

Lee, J. W., Chan, C. W., Chan, J. C., Li, Q. & Lai, J. S. The association between clinical parameters and glaucoma-specific quality of life in Chinese primary open-angle glaucoma patients. Hong Kong Med. J. 20(4), 274–278 (2014).

Mbadugha, C. A., Onakoya, A. O., Aribaba, O. T. & Akinsola, F. B. A comparison of the NEIVFQ25 and GQL-15 questionnaires in Nigerian glaucoma patients. Clin. Ophthalmol. 6, 1411–1419 (2012).

Michopoulos, I. et al. Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS): Validation in a Greek general hospital sample. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 7, 4 (2008).

Skoogh, J. et al. A no means no’—Measuring depression using a single-item question versus hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS-D). Ann. Oncol. 21(9), 1905–1909 (2010).

Bjelland, I., Dahl, A. A., Haug, T. T. & Neckelmann, D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: An updated literature review. J. Psychosom. Res. 52(2), 69–77 (2002).

Organization, W. H. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: Alphabetical Index (World Health Organization, 2004).

Adigun, K., Oluleye, T. S., Ladipo, M. M. & Olowookere, S. A. Quality of life in patients with visual impairment in Ibadan: A clinical study in primary care. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 7, 173 (2014).

Ejiakor, I., Achigbu, E., Onyia, O., Edema, O. & Florence, U. N. Impact of visual impairment and blindness on quality of life of patients in Owerri, IMO state, Nigeria. Middle East. Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 26(3), 127 (2019).

z Mushtaha, M. & Eljedi, A. Y. Quality of life among patients with Glaucoma in Gaza governorates. IUG J. Nat. Stud. 28(1) (2020).

Briesen, S., Roberts, H. & Finger, R. P. The impact of visual impairment on health-related quality of life in rural Africa. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 21(5), 297–306 (2014).

Sung, K. R. et al. Vision-related quality of life in Korean glaucoma patients. J. Glaucoma 26(2), 159–165 (2017).

Degroote, S., Vogelaers, D. & Vandijck, D. M. What determines health-related quality of life among people living with HIV: An updated review of the literature. Archives Public. Health 72, 1–10 (2014).

Wu, N., Kong, X. & Sun, X. Anxiety and depression in Chinese patients with glaucoma and its correlations with vision-related quality of life and visual function indices: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 12(2), e046194 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Department of Adult Health Nursing, College of Medicine, and Health Sciences, Wollo University and Boru Meda general hospital ophthalmology unit for their cooperation during the conduct of the study.

Funding

No financial support was obtained to conduct this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M. conceived the study, drafted, and revised the study proposal, collected the data, and performed data analysis and interpretation. F.S. and S.A.A. prepared data collection instruments and supervised data collection. A.T.K. Edited, drafted, and revised the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review committee of the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wollo University, with reference number CHMS/07/22. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants. All information obtained from the participants was kept confidential, the data were used for research purposes only, and the study protocol followed the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammed, H., Kassaw, A.T., Seid, F. et al. Quality of life and associated factors among patients with glaucoma attending at Boru Meda General Hospital, Northeast Ethiopia. Sci Rep 14, 28969 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77422-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77422-6