Abstract

In clinical nursing, neonatal pain assessment is a challenging task for preventing and controlling the impact of pain on neonatal development. To reduce the adverse effects of repetitive painful treatments during hospitalization on newborns, we propose a novel method (namely pain concept-cognitive computing model, PainC3M) for evaluating facial pain in newborns. In the fusion system, we first improve the attention mechanism of vision transformer by revising the node encoding way, considering the spatial structure, edge and centrality of nodes, and then use its corresponding encoder as a feature extractor to comprehensively extract image features. Second, we introduce a concept-cognitive computing model as a classifier to evaluate the level of pain. Finally, we evaluate our PainC3M on various open pain data sets and a real clinical pain data stream, and the experimental results demonstrate that our PainC3M is very effective for dynamic classification and superior to other comparative models. It also provides a good approach for pain assessment of individuals with aphasia (or dementia).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Newborns have the same pain perception ability as adults. Repeated pain treatment during neonatal intensive care may hurt the development of the brain’s nervous system of newborns, leading to secondary attention, visual, and cognitive impairments1,2. Therefore, there is an urgent need for an automatic and efficient pain assessment means to timely assess neonatal pain, reduce the workload of medical staff, decrease the impact of pain on neonatal development, and improve treatment effectiveness and utilization of medical resources. Usually, “oral reports” are considered the ground truth for pain assessment3, which is an evidence-based and widely recognized assessment tool. However, newborns are unable to report verbally, making the task of assessing neonatal pain very challenging. The existing neonatal pain assessment tools mainly use one-dimensional or multi-dimensional assessment scales, such as neonatal facial coding system (NFCS)4, neonatal infant pain scale (NIPS)5, preterm infant pain profile (PIPP)6, CRIES Neonatal Postoperative Pain Measurement Tool3. Nevertheless, subjective evaluation of neonatal pain based on the scale inevitably leads to many misjudgments. In clinical practice, facial expression is a sensitive and specific biomarker of the level and severity of pain7, and observing the facial state of newborns is relatively simple. Therefore, facial expressions have become a popular choice for pain assessment8,9. Research has shown that using artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to identify, evaluate, understand and treat pain can improve treatment effectiveness and utilization of medical resources10.

At present, the automatic pain recognition methods mostly use deep learning models to process pain indicators such as voice and facial expressions11, electromyography (EMG) and skin electrical response (GSR) signals12, FLIR spectral images13, and electrodermal activity (EDA)14. However, automatically recognizing pain from facial expressions is a challenging question that has attracted great attention15,16. For example, Rodriguez et al.17 applied a Long-Short Term Memory Network (LSTM) for facial pain expression classification and performed well on the binary dataset VGG-Faces. On a small sample dataset, Egede et al.18 combined deep learning features with manual features and used a linear regression model to classify pain levels, achieving good results. Lopez Martinez et al.19 first employed a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) to automatically estimate Prkacin and Solomon Pain Intensity (PSPI) levels from facial images and then used Hidden Conditional Random Fields (HCRF) to estimate VAS, which scores best in a single test sequence. Eidan et al.20 reported in their study that most pain recognition tasks use CNN and LSTM, and although achieving good results, their weaknesses are also very obvious. Even though both LSTM and RNN are good at processing sequences, RNN is hard to parallel, and LSTM has a complex parameter space and long training time. CNN can be parallelized, but it has obvious local dependencies. It requires stacking more layers of filters to achieve global dependencies, which makes the model structure more complex.

In recent years, because of its attention-based sequence processing capability and the ability of its Encoder to parallelize computation, Transformer has been widely used in NLP tasks21,22. With minimal modifications, many works have attempted to directly apply the standard Transformer to images 23,24,25 and graphs26,27 processing tasks, and have also reported ideal results. Though the Transformer can utilize the global and local information of the input, but cannot use the order information of the input. For the lack of inductive biases such as translation equivalence and locality, its generalization ability is insufficient in small sample situations. If an image is directly mapped into a vector, then for the transformer, a too-long input sequence will lead to high computational complexity. When the dataset (with static characteristics) increases, deep networks rely on the support of numerous GPUs, which not only leads to an extreme increase in computing cost but also very high hardware requirements.

In the real-world clinical nursing, a dynamic data is formed by the continuous collection of newborn facial images. The cost of using deep learning models for pain assessment on facial image data streams is high, making the model difficult to apply in practice. However, humans can use known concepts to learn in a natural incremental manner28. This incremental learning not only effectively solves the catastrophic forgetting problem in machine learning, but also can continuously process data stream in reality. Meanwhile, it can integrate and optimize old knowledge while absorbing new knowledge. In our study, different facial expression is used to represent the concept of corresponding pain level, and frequent changes in facial expressions can lead to concept drift. However, deep learning methods are difficult to adapt to such situations, so it is necessary for the model to continuously adjust while receiving data streams, otherwise, concept drift will reduce the accuracy of model learning.

To cope with the above problems, inspired by the attention mechanism21, we propose an approach (namely PainC3M), which uses an improved Vision Transformer (ViT) model for extracting image features and concept-cognitive computing techniques for classification. Specifically, we first improve the attention mechanism of ViT by revising the node encoding way, considering the spatial structure, edge and centrality of nodes, and using its encoder as a feature extractor to comprehensively extract image features. Then, we introduce a concept-cognitive computing model as a classifier to evaluate the level of pain. Compared with CNN and LSTM, it requires less time cost and can perform parallel computation without relying on the previous step’s calculation results. Our proposed approach achieved an accuracy of 97.44%, a precision of 97.46%, a recall of 97.44%, and an F1-score of 97.45% on the real clinical dataset. Our method can not only handle continuous data streams but also effectively deal with the impact of concept drift. The main contributions of this article are: (i) For the first time, the combination of concept-cognitive computing system model and VIT is applied to evaluate infant facial pain, providing a new method for improving clinical nursing level. (ii) We have designed a feature extraction method that integrates information such as the structure, centrality, and edges of a graph into an attention mechanism, which can extract more effective key features.

Related works

Vision transformer

Vision Transformer (ViT) based on self-attention architecture has become the de facto standard for NLP tasks and has achieved good results on large-scale datasets29. The overall framework of ViT is shown in Fig. 1. It divides the 2D image \(\:x\in\:{R}^{H\times\:W\times\:C}\) into a series of flattened 2D patches \(\:{x}_{p}\in\:{R}^{N\times\:({p}^{2}.c)}\), where, (H, W) is the original image resolution, C is denoted as the number of channels, (P, P) is the resolution of each image block, and \(\:N=HW/{P}^{2}\) is known as the number of generated blocks (i.e., the effective input sequence length). Transformer uses a constant vector size D in all its layers. The Transformer flattens the patch and maps it to the D dimension using a trainable linear projection (Eq. (1)), whose output is called patch embeddings. It adds position embedding into patch embeddings to retain location information and use the result as input to the Transformer encoder. For classification purposes, it uses standard methods to add an extra learnable “class token” to the sequence.

Transformer encoder consists of alternating layers of multi-head attention (MSA, Eq. (5)) and MLP blocks (Eqs. (2), (3)). It applies layer norm (LN) before each block and residual connections after each block. MLP contains two layers with GELU nonlinearity.

Concept-cognitive computing system

Concept-cognitive learning (CCL) (that was first proposed by Mi. et al.30,31) is a cross-technology, including formal concept analysis, machine learning, granular computing and dynamic learning, which involves concept learning and knowledge processing in a dynamic environment. In the field of CCL, some recent works have included concurrent classification models (e.g., C3LM32), dynamic classification models (e.g., C3S33 and gC3S34), etc. Concept-cognitive computing (CCC) system is a dynamic concept learning framework. It mainly focuses on how to learn new concepts from different types of data under dynamic environments, and it is usually presented by three aspects of knowledge: storage, learning, and updating. It has good interpretability, as well as classification performance. For the sake of understanding, a set of formal symbols and definitions were briefly described as follows. For more details on the derivations, please refer to the works of Mi et al.33.

Definition 1

Let be a fuzzy formal context. Then for and, the operator can be defined as follows:

Here, we call a pair \(\:(X,\stackrel{\sim}{B})\) a fuzzy concept if \(\:{X}^{*}=\stackrel{\sim}{B,}\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}^{*}=X.\) Meanwhile, X and \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{B}\) of the concept \(\:(X,\stackrel{\sim}{B})\) are known as the extent and intent, respectively. G is an object set and M is an attribute set, and a fuzzy relation between G and M is considered, i.e., \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{I}:G\times\:M\to\:\left[\text{0,1}\right]\). For a universe of discourse M, we denote the set of all fuzzy sets on M by \(\:{L}^{M}\).

Definition 2

Let be a fuzzy-crisp formal decision context. Then for any, the two pairs and are called a fuzzy conditional granular concept (fuzzy concept) and classical decision granular concept (classical concept), respectively. Furthermore, the sets of all fuzzy concepts and classical concepts are denoted as follows:

where \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{F}}}^{c}{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{H}}}^{c}}\) and \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{{\mathcal{F}}^{d}{\mathcal{H}}^{d}}\) are called the fuzzy conditional concept space and classical decision concept space, respectively. For convenience, a fuzzy conditional concept space is also called a concept space in what follows when no confusion exists.

Definition 3

Let be a concept space. For any fuzzy concept and its sub- concept, then the object-oriented fuzzy concept similarity (object-oriented FCS) is defined as

similarly, the attribute-oriented fuzzy concept similarity (attribute-oriented FCS) is defined as

Let \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{F}}}^{c}{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{H}}}^{c}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}}}\) be a subconcept space of \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{F}}}^{c}{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{H}}}^{c}}\) and λ be an object-oriented FCS threshold. When the specific conditions are met, \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{F}}}^{c}{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{H}}}^{c}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}}}\) is known as an object-oriented conceptual cluster of the concept space.

Definition 4

Given an object-oriented FCS threshold λ (), and let be a partition of. Then we can define a new concept space as

For brevity, the concept space \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{F}}}^{c}{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{H}}}^{c}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:},\text{*}}}\) is rewritten as \(\:{\mathcal{G}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:},\text{*}}}\) by omitting the suffix \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{F}}}^{c}{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{H}}}^{c}\) when no confusion exists.

Let \(\:G=\{{x}_{1},{x}_{2},\dots\:,{x}_{m}\}\) be a set of instances and \(\:\mathcal{Y}=\{1,\:2,\:.\:.\:.\:,\:l\}\) be a label space. Note that an instance x is also called an object x in formal concept analysis (FCA). According to the label information, we can ascertain that there exists a partition of the instances into l clusters \(\:{\mathcal{C}}_{1},{\mathcal{C}}_{2},\dots\:,{\mathcal{C}}_{l}\) such that they can cover all the instances, and namely \(\:{\mathcal{C}}_{1}\cup\:{\mathcal{C}}_{2}\cup\:\dots\:\cup\:{\mathcal{C}}_{l}=G\), where \(\:{\mathcal{C}}_{i}\cap\:{\mathcal{C}}_{j}=\varnothing\:\:(\forall\:i\ne\:j)\). Meanwhile, given an object-oriented FCS threshold \(\:\lambda\:=\lambda\:\left(i\right)\:(i\in\:\{\text{1,2},\dots\:,n\left\}\right)\), then the corresponding fuzzy conceptual clusters can be denoted by \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{1}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right),\text{*}}},{\mathcal{G}}_{2}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right),\text{*}}},\dots\:,{\mathcal{G}}_{l}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right),\text{*}}}\). Furthermore, we denote the set of all fuzzy conceptual clusters by \(\:{\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right)}}\), namely \(\:{\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right)}}=\{{\mathcal{G}}_{1}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(1\right),\text{*}}},{\mathcal{G}}_{2}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(1\right),\text{*}}},\dots\:,{\mathcal{G}}_{l}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(1\right),\text{*}}}\}\).

Knowledge storage

The given parameter \(\:\lambda\:\left(i\right)\) is of great importance to construct the concept space. A novel knowledge storage mechanism, falling space, is investigated here. A sample space can be expressed as \(\:{\Omega\:}=\{\lambda\:\left(1\right),\:\:\lambda\:\left(2\right),\dots\:,\lambda\:\left(n\right),\}\), where \(\:\lambda\:\left(i\right)\)is an elementary event. Meanwhile, let\(\:\mathcal{G}=\{{\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(1\right)}},{\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(2\right)}},\dots\:,{\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(n\right)}}\}\) be a set of the whole of concept spaces, and its power set is denoted by \(\:\mathcal{P}\left(\mathcal{G}\right)\).

Definition 5

Let and be two -algebras on the basic space and power set, respectively. For any and, we can define a concept measurable mapping as

Here, given a universe of discourse \(\:\mathcal{G}\), we call \(\:(\mathcal{P}\left(\mathcal{G}\right),\widehat{\mathcal{B}})\) a supermeasurable structure on \(\:\mathcal{G}\), and ξ is known as a random set on \(\:\mathcal{G}\).

Definition 6

Suppose is a random set on the universe of discourse. For any, concept falling with respect to ξ can be defined as

where \(\:{\upxi\:}\left(\lambda\:\left(i\right)\right)\) is called a concept falling space with reference to ξ.

Given a concept space \(\:{\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right)}}\). Suppose the probability of the concept falling \(\:{\mu\:}_{\xi\:}\left({\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right)}}\right)\) is associated with the size of the concept falling space \(\:{\upxi\:}\left(\lambda\:\left(i\right)\right)\). Then we have

This means that the difference of the concept falling \(\:{\mu\:}_{\xi\:}\left({\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right)}}\right)\) can be represented by its probability. Further, given a clue \(\:\lambda\:\left(i\right)\), we can obtain its corresponding concept \(\:{\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right)}}\); if \(\:{\mu\:}_{\xi\:}\left({\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right)}}\right)=1\), then we have the concept space \(\:{\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right)}}\). Similarly, if \(\:{\mu\:}_{\xi\:}\left({\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right)}}\right)=1/n\), then we can also obtain \(\:{\upxi\:}\left(\lambda\:\left(i\right)\right)=\{{\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(1\right)}},{\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(2\right)}},\dots\:,{\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(n\right)}}\}\). Note that, for any \(\:\lambda\:\left(i\right)\), we only consider the scenario of \(\:{\mu\:}_{\xi\:}\left({\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right)}}\right)=1\).

Dynamic concept learning

According to Definition 4, given a parameter \(\:\lambda\:\left(i\right)\), we can obtain its corresponding concept space \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right),\text{*}}}\) with reference to class label k. Suppose Dt and Dt+1 are two different sequential data chunks in a data stream S, and each learning step only processes one data chunk. Then given a data chunk Dt, the concept space \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right),\text{*}}}\)can also be obtained with respect to class label k under the t-th stage.

Definition 7

Given any real concept, and concept similarity threshold, the α-concept neighborhood regarding the concept can be defined as follows:

where sim(·) is a metric function, and the cosine distance is adopted in this paper. Here, \(\:(X,\stackrel{\sim}{B})\) is also regarded as an instance with M-dimensional features.

Definition 8

Let be an α-concept neighborhood with a concept, and be the j-th dimension of the intent of the concept. For real concepts ), then a pair with respect to the α-concept neighborhood can be defined as

where \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}^{\diamond\:}\left({a}_{j}\right)=\:(1/q)\sum\:_{i=1}^{q}{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{i}\left({a}_{j}\right)\). Here, we say that the pair \(\:({X}^{\diamond\:},{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}^{\diamond\:})\) is a virtual concept induced by the α-concept neighborhood \(\:{N}_{\alpha\:,t}(X,\stackrel{\sim}{B})\), and \(\:{X}^{\diamond\:}\)and \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}^{\diamond\:}\) are known as the extent and intent of the virtual concept \(\:({X}^{\diamond\:},{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}^{\diamond\:})\). Hereinafter, real concepts and virtual concepts in this paper are both called concepts when there is no risk of confusion.

The virtual concept is called the extremely abstract representation of a concept space. There is no doubt that this strategy can decrease computation time and improve computation efficiency; however, it will drop the performance significantly due to its extremely abstract representation. Therefore, a strategy of the local α-concept neighborhood (denoted by \(\:{LN}_{\alpha\:,t}(o,*)\)) is adopted for the concept space \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),*}}\). Namely, given a threshold \(\:ϵ\in\:[1,\left|{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),*}}\right|]\), then \(\:ϵ\) real concepts selected from \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),*}}\) can be used for constructing a new virtual concept. Here, a concept space by means of the local α-concept neighborhood is called a compressed concept space, and denoted by \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),\diamond\:}}\).

Let \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),\diamond\:}}\) be a concept space in the t-th stage, and initialize \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),\diamond\:}}=\varnothing\:\). The process of obtaining the compressed concept space (POCCS) \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),\diamond\:}}\) can be described as follows:

Step 1. Select a concept \(\:(X,\stackrel{\sim}{B})\) from the concept space \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),*}}\). If it is a virtual concept, it can be added into \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),\diamond\:}}\) directly; otherwise, we need to consider Step 2.

Step 2. Given a range of concept neighborhood \(\:ϵ\) and a real concept \(\:(X,\stackrel{\sim}{B})\in\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),*}}\). For any real concept \(\:({X}_{i},{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{i})\), if \(\:sim({\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{i},\stackrel{\sim}{B})\ge\:{\upalpha\:}\), then the concept \(\:({X}_{i},{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{i})\) is added into \(\:{LN}_{\alpha\:,t}(X,\stackrel{\sim}{B})\); otherwise, it is added into \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),\diamond\:}}\) directly.

Step 3. If \(\:\left|{LN}_{\alpha\:,t}\right(X,\stackrel{\sim}{B}\left)\right|=ϵ\), the local α-concept neighborhood \(\:{LN}_{\alpha\:,t}(X,\stackrel{\sim}{B})\) is expressed as a virtual concept, and then it is also input into \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),\diamond\:}}\).

Step 4. Select an unvisited concept from the concept space \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),*}}\), and repeat Steps 1–3 until all the concepts in \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),*}}\) are traversed.

Formally, let \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),*}}\) be the concept space in the t-th stage. We denote its compressed concept space by

where \(\:\eta\:\in\:\left(\text{0,1}\right]\) is known as the compression ratio with respect to the original concept space.

Definition 9

Let be the concept space in the t-th stage. For any newly input object, we can get its corresponding concept according to Definition 2. Then we denote

Let \(\:{\widehat{\theta\:}}_{k,j}^{\alpha\:}=\underset{j\in\:\mathcal{J}}{\text{argmax}}\{{\theta\:}_{k,j}^{\alpha\:}\}\), where j represents the j-th concept \(\:\left({X}_{j},{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{j}\right)\), and \(\:\mathcal{J}=\left\{\text{1,2},\dots\:,m\right\}\). Then, considering the whole compressed space (denoted by \(\:{\mathcal{C}}^{{S}_{{\uplambda\:}\left(i\right),\diamond\:}}\)), its corresponding maximum class vector \(\:({\widehat{\theta\:}}_{1,j}^{\alpha\:},{\widehat{\theta\:}}_{2,j}^{\alpha\:},\dots\:,{\widehat{\theta\:}}_{l,j}^{\alpha\:}{)}^{T}\) can be obtained, and the final prediction with the maximum value will be output for our system. Namely,

where \(\:\mathcal{Y}=\left\{\text{1,2},\dots\:,l\right\}\). It represents the instance (or object) \(\:{x}_{r}\) is classified into the \(\:\widehat{k}\)-th class.

Furthermore, given the concept space Ct+1 with reference to a data chunk Dt+1, we further denote

where p = |Ct+1|.

Let Ct+1 be the concept space regarding a data chunk Dt+1 in the (t + 1)-th stage, and \(\:{C}_{t+1}^{1},{C}_{t+1}^{2},\dots\:,{C}_{t+1}^{d}\) be a partition of Ct+1. For the concept space \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),\diamond\:}}\), then we have

where \(\:{{\Theta\:}}_{r}=Sim\_Chunk({C}_{t+1}^{r},{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),\diamond\:}})\).

Given a sample (xr, yr), its prediction value \(\:\widehat{k}\) can be obtained by Eq. (6). It means that the instance xr should be classified into the \(\:\widehat{k}\)-th class.

Updating concept spaces

For updating concept spaces, the instances should be integrated into the existing concept spaces to achieve dynamic learning processes. Given a concept (\(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{H}}}^{c}{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{F}}}^{c}\left({x}_{j}\right),{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{F}}}^{c}\left({x}_{j}\right)\)), its intent can be rewritten as \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{F}}}^{c}({x}_{j},a)(\forall\:a\in\:M)\).

The Process of Updating Concept Space (PUCS). Given a threshold λ(i), let \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{j-1}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right)}}\) be the concept space in the (j-1)-th period. For any concept \(\:({X}_{j-1},{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{j-1})\in\:{\mathcal{G}}_{j-1}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right)}}\), the process of updating concept space can be described as follows:

If \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{B}\left(a\right)\le\:{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{F}}}^{c}({x}_{j},a)(\forall\:a\in\:M)\), then \(\:({X}_{j},{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{j})=({X}_{j-1}\cup\:{x}_{j},{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{j-1})\); if \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{B}\left(a\right)>{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{F}}}^{c}({x}_{j},a)(\forall\:a\in\:M)\), then \(\:({X}_{j},{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{j})=({X}_{j-1}\cup\:{x}_{j},{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{F}}}^{c}({x}_{j},a\left)\right)\); otherwise \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{j}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right)}}\leftarrow\:\:\left(\right\{{x}_{j}\},{\stackrel{\sim}{\mathcal{F}}}^{c}({x}_{j},a\left)\right)\).

In PUCS, if there exists an ordering relation between a new forming concept and any concepts from \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{j-1}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right)}}\), the concept space \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{j-1}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right)}}\) will be updated.

Proposed PainC3M: concept-cognitive computing model for pain assessment

Framework of PainC3M

In our neonatal pain assessment task, we fused the advantages of ViT and C3S models, after improving the attention unit of the ViT model and combining it with the concept-cognitive computing system for pain level recognition, the neonatal pain assessment model PainC3M was developed. The entire framework is shown in Fig. 2. Please note that the baby icon in this figure was from the site (https://www.tukuppt.com/muban/oakxypzv.html).

Our model (i.e., PainC3M) consists of three parts: video collector, feature extractor, and pain classifier. The video collector is in charge of capturing real-time dynamic video streams of newborn facial pain expressions from the nursing scenes using a fixed position non-wide camera. After preprocessing such as sampling, labeling, and denoising, a newborns facial image stream is obtained from the video stream and input to the feature extractor. The feature extractor and pain classifier of PainC3M will be described in detail below.

Feature extractor of PainC3M

Our PainC3M used the attribute-oriented CCC method. Here, the attribute set \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{B}\) is known as the intent of the concept \(\:(X,\:\:\stackrel{\sim}{B})\), which is also the feature set F of the instance that constructs the concept. In our work, extracting the facial features from the newborns’ images is a key task in evaluating the neonatal pain level. Therefore, we first improve the attention unit of ViT and use it as the attention unit of PainC3M (namely, the feature extractor of PainC3M) to obtain more effective image features.

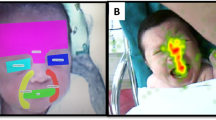

Improving attention unit of ViT by adding structural encoding of graph

In image classification tasks, the attention distribution of the ViT model is calculated based on the semantic correlation between nodes, without effectively considering the structural information of the graph composed of nodes, and has not achieved competitive performance on small datasets. A new graph transformer network that uses identifying useful meta paths and multi-hop connections to learn node representations on the graph is proposed by Yun et al.35, demonstrating the effectiveness of the learned node representations. The graph attention network GAT36 focuses on the adjacent nodes of the graph when implementing attention, considering the case of non-fully connected sparse graphs. To better model graph-structured data, Grapher37 proposed several simple and effective structural encoding methods such as Centrality Encoding, Spatial Encoding, and Edge Encoding, which are most similar to our ideas. The improved ViT attention unit, namely our PainC3M attention unit, is shown in Fig. 3.

Centrality Encoding, as a measure of the importance of nodes in a graph, is usually a powerful signal for understanding the graph. By using centrality encoding in the input, the model can capture semantic correlations and node importance in the attention mechanism. Therefore, degree-based centrality encoding can significantly improve model performance. The input after considering node centrality can be calculated by Eq. (7):

where xi denotes the primitive semantic information of the node, and \(\:{z}_{deg\left({v}_{i}\right)}\) represents the centrality encoding information of degrees (considering the undirected graph case).

Spatial Encoding is introduced to encode the structural information of graphs in the model. Given a graph G, let \(\:{\Phi\:}\left({\text{v}}_{i},{\text{v}}_{j}\right):\:\text{V}\times\:\text{V}\to\:\text{R}\) be the distance of the shortest path between nodes vi and vj. Function Φ defined by the connectivity between nodes in the graph, is used to measure the spatial relationship between nodes in graph G. When vi and vj are not connected, let Φ output − 1. Using Ai, j as the elements of the Transformer’s Query-Key product matrix A, we obtain:

where \(\:{W}_{Q}\) is the weight matrix of Query, \(\:{b}_{{\Phi\:}({v}_{i},{v}_{j})}\) decided by Φ is a learnable scalar of spatial encoding and is shared among all layers as a bias term for the attention module. Thus, the benefits we can gain are: (i) Each node can focus on all other nodes in the graph. (ii) By using \(\:{b}_{{\Phi\:}({v}_{i},{v}_{j})}\), each node in a single Transformer layer can adaptively focus on all other nodes based on the structural information of the graph.

Edge Encoding is more effective for Transformer to capture spatial information on edges. The attention mechanism needs to estimate the correlation of each node pair, and it should consider the edges connecting them. We find the shortest path \(\:{SP}_{ij}=({e}_{1},{e}_{2},\dots\:,{e}_{N})\) from node vi to vj and calculate the average of the edge features and the dot product of learnable embedding along that path. The bias term of the attention module is used to include edge features in our work. By modifying Eq. (8), we can get:

where \(\:{\text{c}}_{ij}=(1/N)\sum\:_{n=1}^{N}{x}_{{e}_{n}}({{w}_{n}^{E})}^{T}.\) \(\:{x}_{{e}_{n}}\)represents the feature of the n-th edge \(\:{e}_{n}\) in SPij, \(\:{w}_{n}^{E}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{{d}_{E}}\) denotes the n-th weight embedding, and dE is the dimension of the edge feature.

Improving transformer encoders by adding dropout layers

Overparameterization and overfitting have always been significant issues in Transformer. Fortunately, as a regularization technique, dropout in Transformer encoders can increase the robustness and generalization ability of the model by randomly discarding a portion of its output, preventing overfitting on training data and improving its performance on new data. Therefore, to improve its performance, we added a dropout layer after the multi-head attention layer (MHA) and MLP block of the Transformer encoders, respectively. The improved Transformer encoder, also known as the PainC3M encoder, is shown in Fig. 4.

Feature extraction

Before extracting image features, image pre-processing is first performed. We divide the image into equal height (H) and equal width (W) patches, use a 16 × 16 convolution kernel with a step size of 16, and convolution [224, 224, 3] images into [14,14,768]. Then flatten the dimensions of H and W, transforming [14, 14, 768] into a two-dimensional matrix of [196, 768], which is divided into 196 tokens, each with a dimension of 768. Finally, embed the class token and concatenate it with the token obtained in the previous step. Class tokens facilitate information exchange with each patch, and the training process converges faster after adding them. Position Embedding is similar to the position encoding of a token, which corresponds to the previously divided patches. Each patch is randomly initialized with a corresponding weight matrix, and finally automatically learned through the network. After the processed patch input into the PainC3M encoder, the processing process is shown in Fig. 4.

Common normalization methods include Layer Normalization (LN)38 and Batch Normalization (BN)39. BN counts the values of all samples on each dimension, calculates the mean and variance, and its distribution is stable on each dimension (local); LN counts the values of all dimensions on each sample, calculates the mean and variance, and its distribution is stable on each sample (global). This work aims to comprehensively consider the correlation factors of image features on a global scale. Therefore, the LN normalization method is chosen. The normalized data is transmitted to the Multi-Head Attention Layer (MHA). MHA concatenates each Head and multiplies it with a weight matrix W, taking into account the fully connected state of all nodes in the graph. Next, to improve model performance, a portion of the output will be randomly discarded through a dropout layer.

The PainC3M attention unit takes into account the structural information of the graph (Eqs. (7), (8), (9)) into matrix A, and then enters the multi-layer perceptron MLP40 module. The calculation result dimension is first enlarged and then reduced to the original dimension. Finally, after a certain degree of regularization through the last dropout layer, the corresponding features of each image are extracted and then concatenated with the class label of the image to output a facial pain feature set as input to the pain classifier of PainC3M.

Pain classifier of PainC3M

The pain classifier structure of PainC3M is shown in Fig. 2 (right part (b)), which evaluates or predicts the pain level of the facial image features extracted in the previous step through a concept-cognitive computing system model. This classifier consists of three parts: knowledge storage, dynamic (concept) learning, and updating concept space. The detailed content of each part of the pain classifier can be seen in Subsection of Concept-cognitive Computing System.

Pain level prediction of PainC3M

This work uses concepts as knowledge carriers, first converting samples into concepts \(\:(X,\:\stackrel{\sim}{B})\) through the induction operator (∙)*, then clustering the concepts into a concept space (i.e. the class t to which the sample belongs), establishing the relationship between the concepts and the concept space, achieve knowledge representation and storage, and the initial concept space denoted as \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{I,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),*}}\). To avoid excessive computational cost caused by excessive conceptual space, a threshold (maxSize) is set to control its size. When the number of samples in a certain class exceeds this threshold, a virtual concept is generated on the concept space, thereby compressing the concept space (denoted as \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),\diamond\:}}\)). Afterward, when new instances arrive, the entire concept space corresponding to them is searched and updated. The concept space update is achieved by calculating the similarity between the new concept and the original cluster. Specifically, if the final prediction (obtained by Eq. (6)) is not consistent with the ground truth, then its corresponding concept \(\:({X}_{\widehat{k},j},\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{\widehat{k},j})\) is called a counteractive concept. If the final prediction is consistent with the ground truth, then we call the corresponding concept \(\:({X}_{\widehat{k},j},\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{\widehat{k},j})\) is an active concept. Here, we call a set of all counteractive concepts a counteractive set, which is denoted by E. Similarly, a set of all the active concepts an active set, which is denoted by C. Therefore, if \(\:\widehat{k}\ne\:{y}_{r}\), the concept \(\:\left({X}_{\widehat{k},j},\:{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{\widehat{k},j}\right)\) will be added into E directly; and vice versa, add the concept into C. For more details, please refer to the study by Mi et al.33.

Pain level prediction of PainC3M with concept drift

Unfortunately, in the process of dynamic learning, those existing concept-cognitive computing algorithms do not consider concept drift34. Hence, their performance may dramatically drop when concept drift occurs in a dynamic learning process, especially for the abrupt concept drift. In our work, the frequent changes in the facial expressions of newborns can lead to frequent conceptual drift. Therefore, to avoid the adverse impact of concept drift on system performance, based on previous work41, we consider concept drift in the dynamic concept learning process.

Definition 1034

Given a data chunk Dt+1 in the (t + 1)-th stage, let aveAccu be the overall average accuracy of data chunks whose range is from D1 to Dt, and currAccu be the accuracy of data chunk Dt+1. Then a classification accuracy that is obtained by comparing the current accuracy with the overall average accuracy is known as an observed accuracy (denoted by obsAccu for convenience). Formally, obsAccu = currAccu − aveAccu.

Let \(\:{\gamma\:}_{w}\) (\(\:{\gamma\:}_{w}\in\:[-\text{1,1}]\)) and \(\:{\gamma\:}_{d}\) (\(\:{\gamma\:}_{d}\in\:[-\text{1,0}]\)) be the thresholds of the concept warning level and concept drift level, respectively. Based on Definition 10, for any new coming data chunk, our system will first detect the observed accuracy, and the process can be described as follows:

-

1.

if obsAccu reaches the warning level, PainC3M starts to invoke the active concept space At+1 as the concept space Ct+1. Formally, if obsAccu > \(\:{\gamma\:}_{w}\), then Ct+1 is replaced with At+1.

-

2.

If obsAccu reaches the drift level, PainC3M will construct a new temp concept space TCt+1 only based on the data chunk Dt+1. Then, the prediction values will be incorporated into our system. Formally, when a new instance xr is available for predictions and obsAccu < \(\:{\gamma\:}_{d}\), the concept space Ct+1 will be regarded as a temp concept space TCt+1. Furthermore, two maximum class vectors \(\:({\widehat{\theta\:}}_{1,j}^{\alpha\:},{\widehat{\theta\:}}_{2,j}^{\alpha\:},\dots\:,{\widehat{\theta\:}}_{l,j}^{\alpha\:}{)}^{T}\) and \(\:({\widehat{\theta\:}}_{1,q}^{\alpha\:},{\widehat{\theta\:}}_{2,q}^{\alpha\:},\dots\:,{\widehat{\theta\:}}_{l,q}^{\alpha\:}{)}^{T}\) are generated based on \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),\diamond\:}}\) and TCt+1, respectively. Then the final maximum class vector can be obtained by the sum of the two maximum class vectors, and the class with the maximum value will be output. It is also worth mentioning that the concept warning level \(\:{\gamma\:}_{w}\) and concept drift level \(\:{\gamma\:}_{d}\) are given by different observers.

Then, the process of updating systems with the concept drift (PUSCD) can simply be described as:

Step 1. Given a data chunk Dt+1, we need to detect the observed accuracy to determine whether the concept warning level (or concept drift level) has or has not occurred at the current period. If the concept warning occurs, the active concept space At+1 will be constructed; if the concept drift occurs, the temp concept space TCt+1 will be generated.

Step 2. Get the counteractive concept spaces Et+1 and Ek, t+1. Similarly, we can also get its corresponding concept space Ct+1 and Ck, t+1 with the k-th class.

Step 3. For any concept \(\:({X}_{j},{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{j})\in\:{E}_{k,t+1}\), \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),*}}\) is replaced with \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),*}}-\left\{\right({X}_{j},{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{j}\left)\right\}\); for any \(\:({X}_{i},{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{i})\in\:{C}_{k,t+1}\), \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),*}}\) is replaced with \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),*}}\cup\:\left\{\right({X}_{i},{\stackrel{\sim}{B}}_{i}\left)\right\}\).

Step 4. Repeat Step 3 until \(\:{\:E}_{t+1}\:!={\varnothing}\)and \(\:{C}_{t+1}\:!={\varnothing}\), and the concept space \(\:{\mathcal{G}}_{k,t+1}^{{S}_{\lambda\:\left(i\right),*}}\) will be obtained.

The improved method is shown in Algorithm 1.

Computational complexity

According to the above analysis, in this subsection, the pseudo-code of PainC3M can be summarized in Algorithm 1. Let the time complexity of constructing a concept space and its corresponding compressed concept space be O(t1) and O(t2), respectively. Then we can get the time complexity of constructing concept spaces is O(t1 + t2). In the meanwhile, given a data chunk Dt+1, let the time complexity of making predictions, constructing concept spaces At+1, Et+1 and Ct+1 be O(t3), O(t4), O(t5) and O(t6), respectively. Based on the above analysis, it is easy to verify that the time complexity of PainC3M is O(t1 + t2 + L(t2 + t3 + t5 + t6 + |At+1|+|Et+1|+|Ct+1|)), where L denotes the number of data chunks.

Experimental evaluation

Experimental settings

All the experiments were performed on a machine with AMD Ryzen 7 4800 H with Radeon Graphics 2.90 GHz @ 2.60 GHz CPU and 4GB main memory. Our system was implemented using Java 1.8.0 and IntelliJ IDEA 2024.1.2 for Windows 10.

To evaluate our model, eight popular dynamic learning methods, namely kNNwithPAW42, ARFHoeddfingTree (ARFHT)43, RuleClassifier (RC)44, CSMOTE45, AccuracyUpdatedEnsemble (AUE2)46, HoeffdingTree (HT)47, OzaBagAdwin (OBA)48, and StreamingGradientBoostedTrees (SGBT)49 are used in our experiments. The descriptions of these methods can be seen in Appendix A.

There are some relevant parameters to be considered in our selected algorithms. For kNNwithPAW, we follow Bifet et al.42, and the number of neighbors k and the max window size w were set as 10 and 1000, respectively. For ARFHoeffdingTree, the number of features per subset for each node split was set to 2. In the RuleClassifier, we set the minimum number of training examples covered by the rule to 50. For AUE2, the number of component classifiers was set to 15. For CSMOTE, we set the number of clusters k to 7. For OzaBagAdwin, the Hoeffding tree was used as the base learner and the ensemble size was 20. For SGBT, we follow Gunasekara et al.49, it used 100 boosting steps (S) to match 100 base learners, its base learner used a variance reduction split criterion, a grace period of 25, a split confidence interval of 0.05, a constant learning rate at the leaves, and the regression tree option. It used a learning rate of 0.0125, and 75% of the features at each boosting step. Furthermore, other parameters of these methods were obtained by default in the MOA framework (https://moa.cms.waikato.ac.nz/). Furthermore, there are three required parameters (i.e., λ, maxSize and chunkSize) and four optional parameters (i.e., \(\:\alpha\:\), \(\:ϵ\), \(\:{\gamma\:}_{w}\) and \(\:{\gamma\:}_{d}\),) in PainC3M. For the parameter λ, it was directly set to be 0.8; for maxSize, it was obtained based on each dataset and was set to 100 by default; the parameter chunkSize was set by following Mi et al.33, and it was selected from {1, 10, 50, 100, 200}. For the concept similarity threshold \(\:ϵ\), it was directly set to be 0.6; for \(\:\alpha\:\) (i.e.,\(\:\alpha\:\)-concept neighborhood), the default setting was 5; the parameter \(\:{\gamma\:}_{w}\) was set to 0 by default, it was selected from [-1,1]; the parameter \(\:{\gamma\:}_{d}\) was selected from [-1,0], it was set to -0.15 by default. All the experiments have been independently implemented 20 times, and the average performance is recorded in this paper.

Similar to previous studies, there are two aspects to consider for dynamic learning, i.e., accuracy and fast adaptation to changes. So, following the commonly used evaluation metrics for data stream algorithms, the classification accuracy and running time of our proposed system are tested. Specifically, for classification accuracy, we evaluate our system from four perspectives: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score. Precision and Recall can be described as Precision = TP/(TP + FP) and Recall = TP/(TP + FN), where TP, FP and FN denote the number of true positives, the number of false positives and the number of false negatives, respectively. F1-score can be considered as a weighted average of the Precision and Recall, i.e., F1-score = 2 × (Precision × Recall) / (Precision + Recall). Moreover, another widely used evaluation metric for dynamic learning methods is running time. For a fair comparison, all these selected methods were performed on the same machine and software environment.

Experimental datasets

Experiments were conducted on three real-world clinical datasets (such as PainSet 1, PainSet 2 and PainSet 3) and three publicly available datasets (such as AffectNet (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/noamsegal/ affectnet-training-data), MMA Facial expressions (abbr., MMA, https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mahmoudima/mma-facial-expression/data), and Facial expression dataset image folders (abbr., Fer2013, https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/astraszab/facial-expression-dataset-image-folders-fer2013)). The details of these datasets are shown in Table 1.

In this paper, all methods were carried out by relevant guidelines and regulations and all experimental protocols were approved by the Artificial Intelligence Ethics Committee of Huaihua University. According to relevant ethics, before collecting newborn information, the informed consent of the newborn’s parents was obtained, and they were aware that their contributions would be used for research. The original samples of PainSet 1, PainSet 2 and PainSet 3 were obtained from facial expression images of infants collected by a local hospital’s neonatal department. A non-wide camera module with a resolution of 1920 × 1080 and a frame rate of 30fps was used to capture the facial images of newborns. Before using these images, professional medical personnel classify and label them. Specifically, two nurses act as labelers to evaluate the same images. If their scores are the same, then label the images directly; If different, they will be sent to the reviewer in the system, who will be a nurse with a professional background in pain management and corresponding clinical work experience, who will conduct the final evaluation of images. If the average difference of evaluation results between the Reviewer’s and the two Labelers’ is within ± 1, the Reviewer’s score will be used as the final score to label the image. Otherwise, the image will be removed from the dataset. Finally, all the images were converted into 224 × 224 pixel jpg format.

PainSet 1.

This dataset consists of 3,437 images of neutral, 18,926 images of pain, and 1,194 images of agony. It was an imbalanced dataset (namely, IR > 2.00) labeled through the above methods.

PainSet 2.

For PainSet 1, due to the significant difference in the number of instances for each type of image, data augmentation methods were adopted to flip, rotate, scale, and partially crop the original images. We expanded the number of the neutral images to 13,478, and the number of the agony images to 10,652. Then, a relatively balanced dataset was obtained and named as PainSet 2.

PainSet 3.

This is an imbalanced dataset with a smaller sample size. It is also generated according to PainSet 1. Specifically, we retained all 3,437 calm images, and then 1,700 and 872 images were selected from pain and agony images, respectively, with a ratio of approximately 4:2:1 for the three types of images.

Due to the lack of a dedicated public dataset for assessing neonatal pain levels, we constructed three clinical pain datasets, PainSet n (n={1,2,3}). To verify the generalization of PainC3M’s classification prediction, three open datasets published by Kaggle, such as AffectNet, MMA, and Fer2013, were selected for facial expression recognition. Here, it should be pointed out that although pain expressions also belong to the category of facial expressions, the three selected open datasets are only used for predicting facial expression types and not for predicting pain.

AffectNet.

This is a large database of faces labeled by “affects” (the psychological term for facial expressions). To accommodate common memory constraints, the resolution of all images was exactly reduced to 96 × 96. All of the monochromatic images were filtered out. There are eight categories: angry, disgust, fear, happy, sad, surprise, contempt, and neutral.

MMA.

The dataset consists of 48 × 48 pixel RGB images of faces and there are seven categories: angry, disgust, fear, happy, sad, surprise, and neutral.

Fer2013.

It consists of 48 × 48 pixel photos of faces expressing different emotions, such as angry, disgust, fear, happy, sad, surprise, and neutral. Its photos are also grayscale images.

In our experiments, we randomly selected 1% of samples from the source dataset for each class as an initial dataset, and then used the entire dataset for dynamic testing.

Experimental results

Experiments on clinical pain data streams

This subsection evaluates the classification performance of our system on three pain data streams (namely, PainSet 1, PainSet 2 and PainSet 3) that were obtained from the clinical nursing department of newborns in hospital. The above-compared methods are tested on these three datasets. For our system and the compared algorithms, the parameter, chunkSize, was set to 100. Table 2 shows the detailed results of our experiments on three pain datasets. As a whole, we can find that our system is superior or highly competitive to others in terms of learning performance, including classification accuracy and time cost. Table 2 indicates that our PainC3M can obtain the least computational time and competitive results for classification performance. Concretely, for small sample imbalanced datasets (PainSet 3, IR = 3. 942), the classification accuracy of our PainC3M is only 0.73% lower than that of the best (OBA), whereas it can get the fastest result in terms of running time. For large sample balanced (PainSet 2, IR = 1.777) and imbalanced datasets (PainSet 1, IR = 15.851), among all comparison algorithms, our PainC3M obtains the best classification accuracy and the least computational time.

Experiments on open expression datasets

In this subsection, three open expression datasets are further used to evaluate the classification performance of PainC3M, namely AffectNet, MMA and Fer2013. They have been described in detail in the section on Experimental datasets. For these datasets, the number of data instances varies from 13,261 to 70,199, and the resolution ranges from 48 × 48 (MMA, Fer2013) to 96 × 96 (AffectNet), covering grayscale (Fer2013) and color (AffectNet, MMA) images. For each dataset, we randomly selected 1% of instances from the original datasets as an initial dataset, and then all instances were used for dynamic learning.

The classification performance (i.e., accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score) and time cost (seconds) of PainC3M on three stream datasets are assessed. Specifically, Tables 3 and 4 profile the detailed classification performance and running time for the different selected algorithms, respectively.

As shown in Table 3, we can see that the overall classification performance of PaniC3M is better than other selected algorithms. For example, PainC3M improved the average classification accuracies about 32.235% (vs. kNNwithPAW), 31.687% (vs. ARFHT), 32.031% (vs. RC), 32.625% (vs. CSMOTE), 30.795% (vs. AUE2), 31.12% (vs. HT), 30.911% (vs. OBA), 17.183% (vs. SGBT), respectively, over three datasets. For Precision, PainC3M also enhanced the average precisions by 35.877%, 36.136%, 40.668%, 36.097%, 33.464%, 34.099%, 34.117% and 16.617% in comparison with kNNwithPAW, ARFHT, RC, CSMOTE, AUE2, HT, OBA and SGBT, respectively. Meanwhile, we observe that our PainC3M can achieve the best results in terms of accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score over these datasets.

From Table 4, we can conclude that our proposed method is the fastest in terms of running time to the other compared algorithms. Concretely, ARFHT is the second fastest among these compared methods, as the Hoeffding bound strategy is used in its learning process. However, the classification accuracy of ARFHT deteriorates. For approaches such as AUE2, HT, OBA and SGBT, although they also maintain high efficiency concerning the overall classification performance, the computational time is not promising on all streaming datasets. Hence, from Tables 3 and 4, it is easy to verify that our PainC3M not only achieves the best classification performance but also performs the best in terms of computing time for various streaming datasets.

At the same time, we also conducted 20 runs with independent sampling each time in a preset proportion for all approaches, and then the averaged performance is reported in Table 5. The learning performance (accuracy and time cost) of PainC3M and some data streaming approaches is indicated in Table 5. We have the same conclusion as above from Table 5. In a word, we can observe that PainC3M performs better than other selected algorithms in terms of overall classification performance and computing time on these three datasets.

Sensitivity analysis

In this subsection, we carefully evaluate the function of the related parameter of PainC3M on three stream datasets, i.e., AffectNet, MMA, and Fer2013. We often fix the other parameters while observing a parameter varying. For example, the parameter, chunkSize (denoted as Cs-i, i = {1,2,3,4,5,6,7}), is fixed when observing the change of maxSize (denoted by Ms-i, i = {1,2,3,4,5,6,7}). For the parameter Cs-i, it was selected from {10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 300, 500}, and the parameter Ms-i was selected from {10, 100, 300, 400, 500, 700, 1000}. The details are shown in Table 6.

Table 6 illustrates the running time (seconds) of our PainC3M with the change of different parameters. The cell Cs-1 in Table 6 represents the first chunkSize value (chunkSize = 10). For example, the values 0.936, 3.787 and 1.023 of the second column of Table 6, respectively, are the running time of PainC3M on AffectNet, MMA, and Fer2013 when Cs-1 = 10. And it has the same meaning for other cells in Table 6 (for instance, the cell Ms-1). From Table 6, we can clearly see that the running time of PainC3M appears an increasing trend when the maxSize grows. The main reason is that the larger the size of maxSize is, the more times a new instance is calculated and the longer it costs. Meanwhile, we can easily observe that the running time of PainC3M shows a decreasing trend when the chunkSize increases. The key reason is that the smaller the size of chunkSize, the more chunks are divided for a given data stream. The smaller data chunk can reduce the computational efficiency compared to the larger data chunk in theory, as the parallel concept learning technique is adopted among different concept subspaces in PainC3M. However, sometimes the running time of our method will be influenced by another significant factor, i.e., PCA for concept drift detection. Computing the PCA of larger data chunks is more time cost than smaller ones. Hence, various factors were comprehensively considered to select the optimal values for the maxSize and chunkSize parameters in our system.

Ablation analysis

In the subsection of Sensitivity analysis, the parameters (i.e., maxSize, and chunkSize) of PainC3M have been analyzed and discussed. Here, we further focus on the impact of PCA in our system. Although PCA has been proven to be suitable for concept drift detection50, it is still necessary to assess its effect in PainC3M. Hence, we conducted the ablation analysis on the PCA of PainC3M. For the sake of simplicity, the system without adopting PCA for classification learning is called PainC3MND.

Table 7 shows the comparison of the classification accuracy between PainC3M and PainC3MND on six datasets. From Table 7, it can be easily seen that PainC3M exhibits better performance (including accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score) than PainC3MND on both the selected open datasets and our clinical pain datasets. This means that using PCA in PainC3M is very useful and necessary for concept drift in the dynamic learning process.

Discussion

Excellent accuracy and time performance of PainC3M on high-dimensional pain data streams

For our model, the quality and time cost of extracting high-dimensional facial pain features are key factors to meet clinical application. Therefore, our system must consider both pain classification accuracy and time-consuming. ViT, a popular large model for processing stream data, was used to conduct experiments on three pain datasets. The results indicate that the quality of the extracted features is positively correlated with the number of image channels and image size, and the overall classification performance improves with the increase of its iteration rounds. However, when ViT achieves a classification effect of over 80%, it takes about 5 h, which makes it difficult to meet the actual clinical needs.

Inspired by the parallel computation of ViT’s encoders in feature extraction, we combine its encoders (i.e. feature extractor) with C3S (i.e. classifier) to form PainC3M (namely, ViT + C3S). Through testing, we found that the classification performance of PainC3M is better than that of the ViT model in the same iteration round, and even the performance of PainC3M in the first round is nearly close to or even better than that of the ViT model in rounds 50–150 on the selected dataset. It can be seen that compared with the ViT model, our PainC3M has better overall performance, especially in terms of time performance, which can meet the needs of clinical use.

To further verify the superiority of PainC3M, we used a 16-layer VGG network51 as a feature extractor and adopted the features output from its second fully connected layer (FC2) as the input for C3S. We conducted classification experiments on three selected identical datasets. The comparison of classification performance between the combined model of VGG and C3S (i.e., VGG + C3S) and PainC3M is shown in Fig. 5.

From Fig. 5, we can clearly see that on the selected three datasets, the classification performance of the model combining VGG with C3S is about 7% worse than ours, which further indicates that PainC3M is more excellent. In other words, in terms of the quality of feature extraction, ViT-based feature extractors are superior to VGG-based ones. In addition, as VGG is a deep convolutional network, on the same dataset, its time-consuming far exceeds that of the ViT model or PainC3M. Hence, the VGG-based model is more difficult to meet clinical needs.

Superior stability and robustness of PainC3M

As mentioned above, we have chosen PainC3M as the newborn pain classification learning model. By visualizing the trend of the loss and accuracy of the model, as shown in Fig. 6, We can intuitively observe the convergence law of the model about the training rounds.

From Fig. 6, It is not difficult to see that the model’s performance in pain recognition is also gradually improving, as the number of iterations increases. By about 600 iterations, the model’s loss and accuracy can converge to the ideal level. It can be seen that the stability and robustness of PainC3M are excellent and satisfactory. In data stream scenarios, our PainC3M can perfectly meet the needs of incremental learning, ensuring the accuracy of infant facial pain recognition over a long period and saving a lot of time cost.

Good practicality of PainC3M in real-world clinical environments

For nurses, of course, obtaining a true accurate assessment of neonatal pain levels in a clinical dynamic environment is still not an easy task. Based on the proposed PainC3M, they can dynamically make classification predictions for neonatal pain and identify the main factors when making incorrect classification predictions. In addition, in the experiments, we have proved that the proposed PainC3M can be used by doctors and nurses to effectively handle dynamic problems, and it is an effective method for processing stream data with high-dimensional features. Table 2 illustrates that the classification performance of PainC3M is mainly determined by the size of datasets, and is also influenced by the imbalance extent of datasets. On balanced big datasets, PainC3M performs the best in classification performance, but poorly on small imbalanced datasets. It can also achieve ideal classification performance on extremely imbalanced big datasets. However, the real-world clinical pain datasets are dynamic, imbalanced, and massive, so using PainC3M to process them is very suitable.

Beyond the traditional pain-assessing process, in which nurses often make conclusions on their own experience, we emphasize that machine-learning approaches can significantly improve the effectiveness of assessments. Our PainC3M can be directly integrated into the hospital information system (abbr. HIS) to build an effective evaluation model in dynamic environments. By using PainC3M, nurses can obtain useful information from dynamic data to support the classification evaluation of neonatal pain. On the whole, the standard machine learning methods can be directly employed to deal with static data. However, for dynamic data, a novel learning mechanism needs to be considered by making a balance between accuracy and running time. In this situation, nurses can consider using our PainC3M for dynamic classification evaluation. It is also worth mentioning that our PainC3M has significant differences from the existing C3S.

-

(i)

In theory, the existing C3S realizes dynamic learning by searching the whole concept space when a new sample arrives. However, this is still time-consuming because when updating concepts, they need to traverse each concept in the concept space. Our PainC3M updates the concept space through data chunks, which can improve the efficiency of dynamic learning.

-

(ii)

The existing C3S mainly focuses on the completion of dynamic processes, without considering concept drift in dynamic data, especially for sudden concept drift. In our proposed system, concept drift detection technology is applied to evolutionary dynamic classification learning.

-

(iii)

Compared to C3S, which only focuses on dynamic classification learning, our PainC3M is an effective ensemble of ViT and C3S. In our model, ViT with an improved attention mechanism is used as a feature extractor, and C3S with concept drift detection function is used as a classifier. This means that the proposed PainC3M considers both time cost and classification accuracy. It is the main reason that using Transformer’s encoder for parallel computing can provide higher feature extraction efficiency, and considering concept drift can achieve better dynamic classification performance.

However, according to the new approaches related to the usage of AI in healthcare, it is demanded to provide explanations for the predicted results. This can be particularly important in healthcare, where physicians and patients may need to understand the rationale behind an AI-generated diagnosis or treatment recommendation. One possible solution to provide explanations for the predicted results of AI models is to use explainable AI (XAI) techniques. For example, Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME)52 is a technique that can be used to explain the predictions of any classifier or regressor by approximating it locally with an interpretable model. In healthcare, this could be used to provide explanations for a particular diagnosis or treatment recommendation made by an AI model. Also, involving clinical experts in the development and validation of AI models to ensure that the explanations provided are relevant and meaningful in a clinical context is an effective strategy.

Conclusion

In our study, a novel approach (PainC3M) was proposed that fuses ViT with C3S to process the neonatal facial pain data streams sampled dynamically from clinical nursing. By improving the attention mechanism of the ViT model and using it as a feature extractor, key features of newborn facial images can be extracted. Meanwhile, by utilizing the parallel computing competence of the Transformer’s encoders, feature vectors are outputted at the encoder layer, effectively reducing the spatiotemporal cost of extracting features. The experimental comparison with other feature extraction methods has verified the superiority of our feature extraction method. Afterwards, to deal with the dynamic continuity of time and space in the collection process of newborn facial data streams and reduce the time cost in the recognition process, we propose a novel concept-cognitive computing framework. This concept-cognitive computing model simulates the process of human cognitive learning. It can simultaneously utilize the extent (object) and intent(attribute) of concepts, effectively store learned knowledge, and automatically update the knowledge inherited in new instances to the concept space in a dynamic environment, achieving effective incremental learning.

Furthermore, PainC3M employed some key technologies, such as concept space compression, parallel concept computing, concept drift processing, etc. It effectively reduces the time and space costs of the system and improves system performance. The experiment shows that our approach achieves better results in comparison with other stream learning methods on the selected datasets with different imbalance ratios (IR), sizes, and resolutions. Meanwhile, PainC3M has lower hardware requirements and can run efficiently on machines equipped with CPUs, making it suitable for clinical applications of large-scale infant facial pain recognition tasks.

In the future, to verify the adaptability and robustness of our model, we will focus on whether the model can effectively utilize the prior knowledge learned from newborns to achieve ideal pain recognition effects in the stages of infants and young children with immature language systems. In addition, it remains a question that needs to be verified whether the model can be applied to individuals with aphasia or dementia is also. At the same time, more research will be conducted on the relationship between key facial regions (i.e., regions of interest (ROIs)) and pain, exploring key feature extraction and dimensionality reduction methods. In addition, for multimodal medical datasets (including brainwave, image, and text etc.), how to design a more universal approach for feature extraction remains an open issue, which is one of the key factors restricting the application of CCL in the clinical field.

Data availability

The clinic datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The other datasets are open and available to access.

References

Doesburg, S. M. et al. Neonatal pain-related stress, functional cortical activity and visual-perceptual abilities in school-age children born at extremely low gestational age. Pain. 154 (10), 1946–1952 (2013).

Mitchell, A. & Boss, B. J. Adverse effects of pain on the nervous system of newborns and young children: a review of the literature. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 34 (5), 228 (2002).

Suraseranivongse, K. A comparison of postoperative pain scales in neonates. Br. J. Anaesth. 97 (4), 540–544 (2006).

Grunau, R. E. et al. Bedside application of the Neonatal Facial Coding System in pain assessment of premature infants. Pain. 76 (3), 277–286 (1998).

Lawrence, J. et al. The development of a tool to assess neonatal pain (NIPS). Neonatal Netw. NN. 12 (6), 59–66 (1993).

Stevens, B. et al. Premature infant Pain Profile: development and initial validation. Clin. J. Pain. 12 (1), 13–22 (1996).

Govindaraj, D. R. An automated pain assessment system using SVM classifier. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 29 (9s), 5463 (2021).

Corns, J. The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of pain (Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315742205

Williams, A.C.C. Facial expression of pain: an evolutionary account. Behav. Brain Sci. 25 (4), 439–455 (2002).

Meina, Z. et al. Using artificial intelligence to improve pain assessment and pain management: a scoping review. Innov. Aging, Supplement_1. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igab046.2409

Singh, S. K. & MIoT Medical internet of things in pain assessment. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-821472-5.00005-3

Sen, K. & Pal, S. Alternative method for pain assessment using EMG and GSR. J. Mech. Med. Biology. 21 (06), 2150039. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219519421500391 (2021).

Krishnan, C., Sandhyavarshini, R. & Jeyakumar, V. Non-clinical pain assessment system—a pilot a study. J. Phys. Conf. Ser., 1917(1), 012008 (2021).

Hossain, M. B. et al. Automatic motion artifact detection in electrodermal activity data using machine learning. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 74, 103483 (2022).

Morabit, S. E. et al. Automatic pain estimation from facial expressions: a comparative analysis using off-the-Shelf CNN architectures. Electronics 2021(16).

Carlini, L. P., Ferreira, L. A., Coutrin, G. A. S., Varoto, V. V. & Thomaz, C. E. Mobile convolutional neural network for neonatal pain assessment. LatinX in Computer Vision (LXCV) workshop - Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (2021).

Rodriguez, P. et al. Deep Pain: exploiting long short-term memory networks for facial expression classification. IEEE Transactions on Cybernatics. 52(2), 3314–3324 (2022).

Egede, J., Valstar, M. & Martinez, B. Fusing deep learned and hand-crafted features of appearance, shape, and dynamics for automatic pain estimation, 12th IEEE international conference on automatic face & gesture recognition (FG 2017). IEEE, 689–696 (2017).

Lopez Martinez, D. & Picard, R. Personalized automatic estimation of self-reported pain intensity from facial expressions, Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops. 70–79 (2017).

Al-Eidan, M., Al-Khalifa, R. & Al-Salman, H. Deep-learning-based models for pain recognition: a systematic review. Appl. Sci. 10 (17), 5984 (2020).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762 (2017).

Vaswani, A. et al. Tensor2Tensor for neural machine translation. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1803.07416 (2018).

Zhang, Y. Double-attention YOLO: vision transformer model based on image processing technology in complex environment of transmission line connection fittings and rust detection. Machines (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/machines10111002

Parmar, N. et al. Image transformer https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1802.05751 (2018).

Li G., Yao H., Le Y., Qin C.. Recaptured screen image identification based on vision transformer. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 90, C. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvcir.2022.103692 (2022).

Yun, S., Jeong, M., Kim, R., Kang, J. & Kim, H. J. Graph Transformer Networks, 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019), Vancouver, Canada (2019).

Ying, C. et al. Do transformers really perform bad for graph representation? 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2021), Sydney, Australia (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. Large scale incremental learning, Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 374–382 (2019).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale, International Conference on Learning Representations. (2021).

Mi, Y. L. et al. Research on granular concept cognitive learning system under MapReduce framework. Acta Electron. Sin.. 46, 289–297 (2018).

Mi, Y. L. Concept-cognitive computing theory and model, Ph.D. dissertation, School of Computer Science and Technology, University of Chinese Academy of SciencesJun., (2020).

Shi, Y., Mi, Y. L., Li, J. H. & Liu, W. Q. Concurrent concept-cognitive learning model for classification. Inf. Sci., 496, 65–81 (2019).

Mi, Y. L., Quan, P. & Shi, Y. Stream Concept-cognitive Computing System for Streaming Data Learning (TechRxiv, 2023).

Mi, Y. et al. Divide and conquer: a granular concept-cognitive computing system for dynamic classification decision making. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 308 (1), 255–273 (2023).

Yun, S. et al. Graph transformer networks. Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Curran Associates Inc., Red Hook, NY, USA, Article 1073, 11983–11993. https://dlnext.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3454287.3455360 (2019).

Veličković, P. et al. Graph attention networks. 6th International Conference on Learning Representations(ICLR) (2018).

Ying, C. et al. Do transformers really perform bad for graph representation ? 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Sydney, Australia (2021).

Ba, J.L., Lei, J.R.K. & Hinton, G.E. Layer Normalization https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1607.06450 (2016).

Santurkar, S., Tsipras, D., Ilyas, A. & Madry, A. How does batch normalization help optimization? Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’18). Curran Associates Inc., Red Hook, NY, USA, 2488–2498. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3327144.3327174 (2018).

Tolstikhin, I. O. et al. Mlp-mixer: an all-mlp architecture for vision. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 24261–24272 (2021).

Lin, J., Wen, W. K. & Liao, J. Y. A novel concept-cognitive learning method for bird song classification. Mathematics. 11 (20), 4298. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11204298 (2023).

Bifet, A., Pfahringer, B., Read, J. & Holmes, G. Efficient data stream classification via probabilistic adaptive windows. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, Coimbra, Portugal, 18–22 March ; p. 801 (2013). (2013).

Gomes, H. M. et al. Adaptive random forests for evolving data stream classification. Machine Learning, Springer (2017).

Gama, J. & Kosina, P. Learning Decision Rules from Data Streams. In Toby Walsh. Proceedings of the Twenty-Second International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Menlo Park, California, USA, s. 1255–1260 (2011).

Bernardo, A., Gomes, H. M., Montiel, J., Pfahringer, B. & Valle, E. D. C-smote: Continuous synthetic minority oversampling for evolving data streams, IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), IEEE (2020). (2020).

Brzezinski, D. & Stefanowski, J. Reacting to different types of concept drift: the accuracy updated ensemble algorithm. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 25 (1), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2013.2251352 (2013).

Cal, P. & Woniak, M. Parallel hoeffding decision tree for streaming data. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-00551-5_4 (2013).

Bifet, A. et al. New Ensemble Methods for Evolving data Streams, Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (ACM, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1145/1557019.1557041

Gunasekara, N., Pfahringer, B., Gomes, H. & Bifet, A. Gradient boosted trees for evolving data streams[J]. Mach. Learn. 113 (5), 3325–3352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10994-024-06517-y (2024).

Wan, S. W. & Wang, S. D. Concept drift detection based on pre-clustering and statistical testing. J. Internet Technol. 2, 22 (2021).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. Comput. Sci. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1409.1556 (2015).

Ribeiro, M. T., Singh, S. & Guestrin, C. Why should I trust you? Explaining the predictions of any classifier[J]. ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939778 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge support for this work from the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Scientific Research Projects of the Hunan Provincial Department of Education.

Funding

This work was funded by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 2024JJ7374, No. 2023JJ50456, No. 2024JJ7383), and the Scientific Research Projects of the Hunan Provincial Department of Education (No. 21A0488, No. 22A0547, No. 23B0719, No. 23A0556).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LZ and YZ collected and preprocessed newborn image data, conducted the study, and classified and labeled the data. JL designed and supervised the study. JL, LZ, and JX have discussed and proposed the feature extraction and classier learning approach and equally contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, J., Zhang, L., Xia, J. et al. Evaluating neonatal pain via fusing vision transformer and concept-cognitive computing. Sci Rep 14, 26201 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77521-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77521-4