Abstract

There is a significant interrelationship between cardiovascular disease and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), as they share common risk factors and comorbidities. This study aimed to investigate the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of inpatients with cardiovascular disease towards OSA. This cross-sectional study was conducted between January, 2022 and January, 2023 at Zhongda Hospital Affiliated to Southeast University among inpatients with cardiovascular disease using a self-administered questionnaire. A self-designed questionnaire was used to assess KAP, and the STOP-Bang questionnaire was applied to evaluate participants’ OSA risk. Spearman correlation and path analyses were conducted to explore relationships among KAP scores and high OSA risk. Subgroup analyses were conducted within the high-risk population identified by the STOP-Bang questionnaire. In a study analyzing 591 questionnaires, 66.33% were males. Mean scores were 6.81 ± 4.903 for knowledge, 26.84 ± 4.273 for attitude, and 14.46 ± 2.445 for practice. Path analysis revealed high risk of OSA positively impacting knowledge (β = 2.351, P < 0.001) and practice (β = 0.598, P < 0.001) towards OSA. Knowledge directly affected attitude (β = 0.544) and practice (β = 0.139), while attitude influenced practice (β = 0.266). Among high OSA risk individuals, knowledge directly impacted attitude (β = 0.645) and practice (β = 0.133). Knowledge indirectly influenced practice via attitude (β = 0.197). Additionally, attitude directly affected practice (β = 0.305). These findings provide insights into the interplay between OSA risk, knowledge, attitude, and practice. Inpatients with cardiovascular disease demonstrated inadequate knowledge, moderate attitude, and practice towards OSA. The findings highlighting the need for targeted educational interventions to improve awareness and management of OSA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), a widespread sleep disorder affecting around one billion adults globally, is characterized by repeated episodes of obstructive apnea and hypopnea during sleep1,2,3. Despite being the most prevalent respiratory sleep disorder, OSA often goes undiagnosed4. It shares common risk factors and comorbid conditions with cardiovascular disease, establishing itself as an independent risk factor for this condition5. The diagnosis rate for OSA is notably low, estimated at approximately 34% in men and 17% in women in the general population, highlighting its significant health implications, especially for individuals with cardiovascular issues6. The severe disruption to sleep quantity and quality caused by OSA results in sleep deprivation, emphasizing its critical status as a public health concern, particularly for those with cardiovascular disease4.

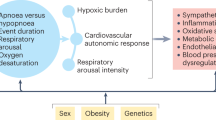

OSA is characterized by intermittent narrowing or collapse of the upper airway during sleep, leading to partial or complete cessation of airflow. These repeated episodes of airway obstruction result in disrupted breathing and fragmented sleep patterns. The obstruction of the airway in OSA patients triggers several pathophysiological processes, including decreased oxygen saturation, elevated carbon dioxide levels, fluctuations in intrathoracic pressure, sympathetic nervous system activation, and frequent arousals, with hypoxemia being a key pathological factor7,8. The intermittent hypoxia induced by OSA leads to a cascade of events that contribute to the onset and progression of cardiovascular diseases. Specifically, OSA-related hypercapnia, increased intrathoracic negative pressure, and arousal fluctuations exacerbate the progression of cardiovascular conditions9. Additionally, OSA is associated with a prothrombotic state, characterized by elevated levels of thrombogenic factors such as fibrinogen and platelet activation, which further heightens the risk of cardiovascular complications10.

Prior research has revealed that the prevalence of OSA among individuals with coronary artery disease (CAD) ranges from 30 to 69%. Furthermore, OSA has been shown to substantially increase the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, particularly in individuals already suffering from cardiovascular conditions. Given the clear relationship between these two ailments, individuals with cardiovascular disease must be cognizant of the necessity to identify and address OSA11,12,13.

The Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices (KAP) survey functions as a research tool, providing insights into a group’s comprehension, beliefs, and actions on a specific subject, particularly within the realm of health literacy, based on the premise that knowledge positively influences attitudes, which in turn shape behaviors14,15,16. Given the intricate interplay between OSA and cardiovascular disease, it is crucial to investigate the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of individuals affected by cardiovascular ailments regarding OSA. This exploration holds significance in identifying risk factors among cardiovascular disease inpatients, which may enable the implementation of relevant interventions such as OSA screening and treatment to mitigate the risks of cardiovascular events. Additionally, examining into the awareness and conduct of cardiovascular disease inpatients regarding OSA provides insights that empower healthcare professionals to better educate and guide this specific patient cohort. This, in turn, fosters improved adherence to treatment regimens, with the ultimate goal of enhancing the efficacy of treatment and cardiovascular disease management. It is important to note that while there is a wealth of KAP research focused on healthcare practitioners regarding OSA, there is a conspicuous dearth of research concerning inpatients with cardiovascular disease17,18,19.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the KAP of inpatients with cardiovascular disease towards OSA.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted between January, 2022 and January, 2023 at Zhongda Hospital Affiliated to Southeast University among inpatients with cardiovascular disease by random sampling. The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Zhongda Hospital Affiliated to Southeast University and obtained informed consent from all participants.

Inclusion Criteria: (1) Patients requiring inpatient treatment in the cardiology department due to cardiovascular disease; (2) aged > 18 years old.

Exclusion Criteria: (1) Inability to understand the questionnaire correctly, (2) inability to cooperate in answering the questionnaire, (3) mental disorders, and other factors that may affect the authenticity of the questionnaire, (4) Patients who were diagnosed with OSA or under treatment for OSA.

Questionnaire

The final questionnaire is presented in the Chinese language and encompasses five distinct sections: the STOP-Bang questionnaire, demographic characteristics, knowledge dimension, attitude dimension, and practice dimension.

The STOP-Bang questionnaire was specifically designed to fulfill the demand for a dependable, succinct, and user-friendly screening instrument. It comprises eight binary (yes/no) items pertaining to the clinical characteristics of sleep apnea, with a total score spanning from 0 to 8, and patients scoring ≥ 3 were considered at high risk of OSA, demonstrating high sensitivity and specificity among Chinese population20,21,22. The STOP-BANG questionnaire was completed with the assistance of trained medical staff. The staff collected objective measurements such as height, weight, and neck circumference upon admission and asked relevant questions to both the participants and their cohabitants. Based on these responses, healthcare providers assessed the risk of OSA.

The development of the KAP questionnaire was informed by previous study23 and clinical experience. Subsequently, the initial design was refined through feedback received from 3 senior experts (one expert in OSA with experience over 20 years and two experts in cardiovascular disease with experience over 20 years), ensuring content validity. A pilot study was then conducted among 22 patients, which yielded a reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s α) of 0.814, indicated a good internal consistency. During the pilot study, no items in the questionnaire were deemed unreadable after explanation, suggesting adequate face validity. A post hoc Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to evaluate construct validity. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy for the questionnaire was 0.960 (P < 0.001), indicating that the data were highly suitable for factor analysis. CFA demonstrated that the model had an acceptable fit. The chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (CMIN/DF) was 3.544, falling within the ‘Good’ range (1–3: Excellent, 3–5: Good). The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.066, which is below the 0.08 threshold, indicating a good fit. Additionally, the Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) were 0.814, 0.805, and 0.813, respectively, all exceeding the acceptable threshold of 0.8 (Supplementary Fig. 1) (Supplemental Table 1).

The KAP survey assessed three dimensions: knowledge, focused on awareness of OSA’s symptoms, risk factors, associated conditions, and treatment options; attitude, which examined perceptions of the impact and treatability of OSA; and practice, which explored behaviors related to monitoring, prevention, and willingness to seek treatment for OSA. In the knowledge dimension, questions 1–5 are allotted a scored 2 points for correct responses and 0 points for incorrect answers. Conversely, questions 6–9 are evaluated based on participants’ comprehension of relevant issues, with a scoring system of 0 points for participants who expressed understanding for 0–3 items, 1 point for those understanding 4–6 questions, and 2 points for those understanding 7 or more questions. The cumulative knowledge score ranges from 0 to 18 points. For the attitude dimension, seven questions are rated on a five-point Likert scale, spanning from “strongly agree” (5 points) to “strongly disagree” (1 point), yielding scores ranging from 7 to 35. In the practice dimension, five questions are presented, with questions 1–4 utilizing a five-point Likert scale. Scores in this dimension range from 4 to 20 points. For high-risk OSA patients, additional inquiries were made in the attitude dimension regarding their attitudes towards OSA prevention and in the practice dimension regarding their willingness to engage in OSA treatment and prevention. Given the limited number of participants at high risk of OSA, only descriptive analysis was conducted for these additional questions. The demographic characteristics and KAP dimensions were collected using electronic questionnaires generated by “Questionnaire Star” platform. Participants generally completed the questionnaires independently, although trained research assistants were available to provide unbiased assistance if participants encountered confusion or difficulties.

Participants who scored above 80% of the total were categorized as having adequate knowledge, positive attitude, and proactive practice. Those with scores in range of 60–80% of the total indicated inadequate knowledge, attitude, and practice. Scores below 60% of the total were indicative of inadequate knowledge, negative attitude, and inactive practice24.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) was utilized for statistical analysis. Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and compared by t-tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA). Categorical variables were presented as n (%). Spearman correlation analysis was employed to assess the correlations among knowledge, attitude, and practice scores. A path analysis was conducted to explore the relationships among the three dimensions (knowledge, attitude, and practice) and high risk of OSA. Subgroup analysis was conducted within the high risk population identified by the STOP-Bang questionnaire. A two-sided P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Initially, a total of 678 questionnaires were collected in the study, and 87 of them were excluded for too short responses time (n = 67), logical errors (n = 9), or obvious patterns of responses (n = 11). Therefore, 591 valid questionnaires were analyzed, with a validity rate of 87.17%. Among them, 392 (66.33%) were male, 366 (61.93%) were aged over 55. Out of the participants, 288 (48.73%) had sought medical assistance for coronary heart disease, while 311 (52.62%) reported snoring but had not sought medical attention. A total of 196 (33.16%) had experienced daytime sleepiness, lack of concentration, or similar issues during the day. Moreover, 148 (25.04%) were assessed to be at high risk of OSA. The majority of participants reported acquiring health information through online media (65.65%, n = 388) and traditional media such as TV and newspapers (64.13%, n = 379), followed by conversations with family and friends (42.64%, n = 252) and education from healthcare professionals (40.44%, n = 239), with a smaller proportion relying on other sources (5.08%, n = 30) (Table 1).

KAP towards OSA

The mean knowledge, attitude, and practice scores were 6.81 ± 4.90 (possible range: 0–18), 26.84 ± 4.27 (possible range: 7–35), and 14.46 ± 2.45 (possible range: 4–20), respectively. The knowledge, attitude, and practice scores varied from inpatients across weight, residence, education, monthly income, medical-related occupation, snoring, experience of daytime sleepiness, lack of concentration, or similar issues during the day, and whether they are at high risk of OSA (all of P < 0.01). Meanwhile, those with different occupation and different reasons for seeking care are more likely to have different knowledge and attitude scores (all of P < 0.05). Furthermore, differences in age (P = 0.003), type of medical insurance (P = 0.001), and BMI (P = 0.018) may also lead to differences in knowledge scores (Table 1).

The knowledge dimension of the overall population shows that 54.15% are aware that OSA leads to increased respiratory effort, decreased oxygen saturation, and increased cardiac load (K1), and 61.42% are aware that snoring does not equate to a good sleep quality (K2), while 51.61% are still uncertain about the correlation between the degree of snoring and the severity of OSA (K5). When it comes to factors that increase the risk of OSA (K6), the most well-known are obesity (68.53%) and being male (54.15%). Regarding symptoms caused by OSA (K7), the most known were snoring (55.5%) and breathing pauses (44.33). However, only 44.84% and 40.61% participants were aware that OSA may be associated with hypertension and coronary artery disease, respectively (K8). For the treatment of OSA (K9), weight loss (58.71%) and exercise (54.99%) were the most known (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Regarding the attitude, 68.86% agreed or strongly agreed that treatment of OSA is necessary (A2). The vast majority (86.8%) believed that learning about OSA is necessary (A6). Meanwhile, 83.93% agreed to varying degrees that OSA is more dangerous for patients with heart and cardiovascular diseases (A7) (Supplemental Fig. 3). The practices also varied considerably, 57.36% reported a willingness to seek medical attention when experiencing symptoms of OSA (P3), and 87.48% reported a willingness to improve lifestyle habits in order to prevent the onset of OSA (P4). It is noteworthy that participants preferred to be educated about OSA by communicating with their doctor, either online or offline, much more than any other method (P5) (Supplemental Fig. 4).

Correlation among KAP

The correlation analysis identified significant positive correlations between knowledge and attitude (r = 0.615, P < 0.001), knowledge and practice (r = 0.569, P < 0.001), as well as attitude and practice (r = 0.568, P < 0.001), respectively (Table 2). Path analysis results revealed a direct positive impact of high risk for OSA on knowledge (β = 2.351, P < 0.001) and practice (β = 0.598, P < 0.001) towards OSA. Conversely, knowledge exerted a direct positive effect on attitude (β = 0.544, p <0.001) and practice (β = 0.139, P < 0.001), meanwhile, attitude also significantly and directly influenced practice (β = 0.266, P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Subgroup analysis among participants at high risk of OSA

A subgroup analysis was conducted among participants at high risk of OSA (Table 4). Among participants with high risk of OSA, 68.25% of them were willing to undergo regular screening for OSA (P6), and when OSA was diagnosed, the most accepted treatment was by improving lifestyle habits (89.86%) (Supplementary Fig. 5A). The most desired reasons for receiving treatment were to improve sleep quality (68.92%) and to reduce snoring (64.19%) (Supplementary Fig. 5B). When it comes to the reasons for choosing not to receive treatment, the most important reasons were uncertainty about the efficacy of the treatment (50.00%) and the high cost (49.32%) (Supplementary Fig. 5C). Only 20.95% fully complied with the medical advice to wear a ventilator (P14), and the most important factors affecting their willingness to do so were, in descending order, the inconvenience of use, feeling congested nose, the need to wear a mask tightly, tight mask fit, and the high cost of the treatment (more than 40% in each item) (Supplementary Fig. 5D) (Supplemental Table 2). And the path analysis showed that their knowledge directly affects attitude (β = 0.645, P < 0.001) and practice (β = 0.133, P < 0.001), and that their knowledge also has an indirect effect on practice through attitude (β = 0.197, P = 0.005), moreover, their attitude also directly affects practice (β = 0.305, P < 0.001) (Supplemental Table 3).

Discussion

This study represents the first exploration of KAP toward OSA among inpatients with cardiovascular disease. Our findings reveal inadequate knowledge, moderately positive attitudes, and suboptimal practices among this population, consistent with previous research on OSA awareness in the general population25. Given the established bidirectional relationship between OSA and cardiovascular outcomes, addressing these deficiencies is critical for improving patient care and outcomes. To address this deficiency, healthcare providers should consider implementing targeted educational interventions that emphasize the interplay between OSA and cardiovascular health. Such interventions could include the development of evidence-based educational materials and the integration of OSA discussions into routine cardiovascular consultations. These recommendations are supported by previous research underscoring the importance of patient education and effective healthcare provider communication in enhancing health outcomes among individuals with cardiovascular conditions26,27.

Notably, these scores exhibited considerable variability based on several demographic and health-related factors. Furthermore, the age of patients and the type of medical insurance they hold demonstrated statistically significant associations with differences in knowledge scores. These findings highlight the need for tailored interventions that consider the multifaceted nature of these determinants to improve clinical practice, resonate with the previous study, where similar demographic factors played a pivotal role in shaping patient attitudes and practices28. To address this, healthcare providers should consider implementing educational initiatives targeting these specific factors, thereby enhancing knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to OSA in patients with cardiovascular disease29. Moreover, these results call for further investigation into the effectiveness of such tailored interventions and their impact on clinical outcomes and patient well-being, thereby promoting more patient-centered and holistic care30,31.

In our study, patients diagnosed with cardiovascular disease displayed a concerning lack of knowledge about OSA. This knowledge deficit is highlighted by the low percentages of correct responses to questions related to OSA, especially its symptoms, risk factors, and treatment options. To address these deficiencies and improve clinical practice, healthcare providers should prioritize patient education and awareness initiatives that cover a comprehensive range of OSA-related topics29,32.

Our analysis revealed that patient attitudes toward OSA were moderately positive, with many recognizing it as a treatable condition impacting overall health. However, a significant portion expressed neutral or negative attitudes regarding its effects on daily life and treatment outcomes. These findings suggest a need for more comprehensive patient education programs that not only provide factual information but also address misconceptions and emphasize the potential benefits of early diagnosis and treatment. Such programs could potentially improve patient attitudes and, consequently, treatment adherence, as suggested by previous studies on the relationship between patient attitudes and health behaviors33,34.

The results of this study illuminate critical aspects of patients’ practices regarding OSA and underscore opportunities for improvement in clinical practice. To enhance clinical practice, it is imperative to harness these observations. Tailored educational programs, particularly those focusing on the self-assessment of OSA symptoms, should be developed and offered to patients35,36.

Within this study, we explored high-risk OSA populations as distinct subgroups, shedding light on their perspectives and behaviors. A significant proportion of this high-risk group exhibited a willingness to undergo regular screening for OSA, reflecting a proactive stance in managing their health. However, this optimism is countered by a notable compliance gap, with only a fraction adhering to medical advice regarding ventilator use, despite their willingness to screen for OSA. This deviation from established recommendations contrasts with existing research, where continuous positive airway pressure is consistently identified as the preferred treatment for OSA37,38. This compliance deficiency is exacerbated by a range of factors, including the inconvenience of device use, discomfort related to mask fit, and concerns about treatment costs. Intriguingly, the most sought-after aspects of treatment revolved around improving sleep quality and reducing snoring, emphasizing patients’ desires for enhanced sleep experiences and an improved quality of life. Conversely, the decision to forego treatment appeared to be rooted in concerns about treatment efficacy and financial burden, raising questions about the perceived effectiveness of OSA interventions and access to affordable care.

Aligned with existing literature, the findings highlight the profound impact of socio-demographic factors on OSA-related KAP among the high-risk subgroup. Higher education levels have been consistently linked to improved health literacy and better health literacy39. Similarly, increased income facilitates access to healthcare resources and promotes healthier behaviors40. Urban residency is associated with better healthcare access and information, which aligns with findings of improved practice outcomes among urban residents41. Furthermore, participation in educational programs has shown to effectively enhance knowledge and self-management skills42, which is consistent with the observed improvement among participants in educational programs. Additionally, higher BMI, often associated with OSA, necessitates targeted interventions focusing on weight management to improve OSA outcomes. Based on a detailed analysis of the inter-group comparison results among high-risk populations, tailored recommendations can be devised to address specific needs and circumstances across demographic and socio-economic groups. For individuals with lower educational attainment and income levels, targeted educational interventions are essential to bridge knowledge gaps and foster positive attitudes towards OSA management, in addition to financial assistance programs to alleviate cost burdens. In contrast, among those with higher education and income levels, initiatives should focus on enhancing adherence to treatment plans through personalized counseling and leveraging digital health platforms, while workplace wellness programs can promote healthy sleep habits43. Additionally, involving spouses or partners in educational sessions can facilitate mutual support and shared decision-making. By customizing interventions to the unique needs and circumstances of diverse demographic groups, healthcare providers can effectively optimize OSA management outcomes and improve overall quality of life for high-risk populations.

Our correlation analysis demonstrated significant positive relationships between knowledge, attitude, and practice components of OSA management. These findings are consistent with established health behavior models and emphasize the interconnected nature of these elements in shaping patient behavior42,44,45.

To enhance the role of healthcare providers in OSA management, several evidence-based strategies could be implemented. These include the development of standardized OSA screening protocols for cardiovascular inpatients, the establishment of interdisciplinary sleep health teams, and the provision of continuing education on OSA management for healthcare professionals. Such approaches have been shown to improve the detection and management of comorbid conditions in other areas of medicine and may be equally beneficial in the context of OSA and cardiovascular disease46,47.

This study has several limitations. The cross-sectional design restricts our ability to infer causal relationships. A path analysis was performed as a surrogate of causality, but the results must be interpreted cautiously since they were statistically inferred48. Additionally, potential biases in self-reported data and sampling limitations may affect the generalizability of the findings. The study’s focus on inpatients with cardiovascular disease also limits the broader applicability of the results. Social desirability bias and the omission of variables that could influence knowledge, attitude, and practice are additional potential limitations.

In conclusion, this study highlights significant deficiencies in knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding OSA among cardiovascular inpatients. These findings underscore the need for comprehensive, evidence-based interventions to improve OSA management in this high-risk population. By addressing knowledge gaps, fostering positive attitudes, and promoting treatment adherence, we may potentially improve both OSA management and cardiovascular outcomes. Future research should focus on developing, implementing, and evaluating the effectiveness of targeted interventions to optimize patient care and health outcomes in this population.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Heda, P. et al. Long-term periodontal changes associated with oral appliance treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 17, 2067–2074 (2021).

Sillanmäki, S. et al. QTc prolongation is associated with severe desaturations in stroke patients with sleep apnea. BMC Pulm Med. 22, 204 (2022).

Zhou, J., Bai, W., Liu, Q., Cui, J. & Zhang, W. Intermittent Hypoxia Enhances THP-1 Monocyte Adhesion and Chemotaxis and Promotes M1 Macrophage Polarization via RAGE. Biomed Res Int. ; 2018:1650456. (2018).

Wasey, W., Wasey, N., Manahil, N., Saleh, S. & Mohammed, A. Hidden dangers of severe obstructive sleep apnea. Cureus. 14, e21513 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. The impact of left ventricular geometry on left atrium phasic function in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a multimodal echocardiography investigation. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 21, 209 (2021).

Gottlieb, D. J. & Punjabi, N. M. Diagnosis and management of obstructive sleep apnea: a review. Jama. 323, 1389–1400 (2020).

Kajiyama, T., Komori, M., Hiyama, M., Kobayashi, T. & Hyodo, M. Changes during medical treatments before adenotonsillectomy in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Auris Nasus Larynx. 49, 625–633 (2022).

Wojeck, B. S. et al. Ertugliflozin and incident obstructive sleep apnea: an analysis from the VERTIS CV trial. Sleep. Breath. 27, 669–672 (2023).

Bommineni, V. L. et al. Automatic segmentation and quantification of Upper Airway Anatomic Risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea on unprocessed magnetic resonance images. Acad. Radiol. 30, 421–430 (2023).

Xu, J. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea aggravates neuroinflammation and pyroptosis in early brain injury following subarachnoid hemorrhage via ASC/HIF-1α pathway. Neural Regen Res. 17, 2537–2543 (2022).

Cepeda-Valery, B., Acharjee, S., Romero-Corral, A., Pressman, G. S. & Gami, A. S. Obstructive sleep apnea and acute coronary syndromes: etiology, risk, and management. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 16, 535 (2014).

Liu, Y., Wang, M. & Shi, J. Influence of obstructive sleep apnoea on coronary artery disease in a Chinese population. J. Int. Med. Res. 50, 3000605221115389 (2022).

Peker, Y., Hedner, J., Kraiczi, H. & Löth, S. Respiratory disturbance index: an independent predictor of mortality in coronary artery disease. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 162, 81–86 (2000).

Khalid, A. et al. Promoting health literacy about Cancer Screening among Muslim immigrants in Canada: perspectives of imams on the Role they can play in Community. J. Prim. Care Community Health. 13, 21501319211063051 (2022).

Koni, A. et al. A cross-sectional evaluation of knowledge, attitudes, practices, and perceived challenges among Palestinian pharmacists regarding COVID-19. SAGE Open. Med. 10, 20503121211069278 (2022).

Shubayr, M. A., Kruger, E. & Tennant, M. Oral health providers’ views of oral health promotion in Jazan, Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 23, 214 (2023).

Devaraj, N. K. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding obstructive sleep apnea among primary care physicians. Sleep. Breath. 24, 1581–1590 (2020).

Nguyen, V. T. Knowledge, attitude, and clinical practice of dentists toward obstructive sleep apnea: a literature review. Cranio. 41, 238–244 (2023).

Nwosu, N. et al. Knowledge attitude and practice regarding obstructive sleep apnea among medical doctors in Southern Nigeria. West. Afr. J. Med. 37, 783–789 (2020).

Chung, F., Abdullah, H. R., Liao, P. & STOP-Bang Questionnaire A practical Approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 149, 631–638 (2016).

Teng, Y., Wang, S., Wang, N. & Muhuyati STOP-Bang questionnaire screening for obstructive sleep apnea among Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch. Med. Sci. 14, 971–978 (2018).

Zheng, Z. et al. Application value of joint STOP-Bang questionnaire and Epworth Sleepiness Scale in screening for obstructive sleep apnea. Front. Public. Health. 10, 950585 (2022).

Sia, C. H. et al. Awareness and knowledge of obstructive sleep apnea among the general population. Sleep. Med. 36, 10–17 (2017).

Thirunavukkarasu, B. F. A. L. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards evidence-based Medicine among Northern Saudi Primary Care Physicians: a cross-sectional study. Healthc. (Basel) 10(11), 2285 (2022).

Pan, Z. et al. People’s knowledge, attitudes, practice, and healthcare education demand regarding OSA: a cross-sectional study among Chinese general populations. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1128334 (2023).

Fukuoka, Y. et al. Baseline feature of a randomized trial assessing the effects of disease management programs for the prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 24, 610–617 (2015).

Biglino, G. et al. 3D-manufactured patient-specific models of congenital heart defects for communication in clinical practice: feasibility and acceptability. BMJ Open. 5, e007165 (2015).

Huang, S. et al. Oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices and oral health-related quality of life among stroke inpatients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 22, 410 (2022).

Kumar, S. et al. Assessment of Patient Journey Metrics for users of a Digital Obstructive Sleep Apnea Program: single-arm feasibility pilot study. JMIR Form. Res. 6, e31698 (2022).

Seixas, A. A. et al. Culturally tailored, peer-based sleep health education and social support to increase obstructive sleep apnea assessment and treatment adherence among a community sample of blacks: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 19, 519 (2018).

Sutherland, K., Kairaitis, K., Yee, B. J. & Cistulli, P. A. From CPAP to tailored therapy for obstructive sleep Apnoea. Multidiscip Respir Med. 13, 44 (2018).

Kim, Y. R. Mediating effect of self-cognitive oral health status on the effect of obstructive sleep apnea risk factors on quality of life (HINT-8) in Middle-aged Korean women: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Life (Basel). 12(10), 1569 (2022).

Mahdi, A., Svantesson, M., Wretenberg, P. & Hälleberg-Nyman, M. Patients’ experiences of discontentment one year after total knee arthroplasty- a qualitative study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 21, 29 (2020).

Makhinova, T. et al. Improving asthma management: patient-pharmacist partnership program in enhancing therapy adherence. Pharm. (Basel) 10(1), 34 (2022).

Cho, J. et al. Snoring during bronchoscopy with moderate sedation is a predictor of obstructive sleep apnea. Tuberc Respir Dis. (Seoul). 82, 335–340 (2019).

Mohammadi, I. et al. Evaluation of blood levels of Omentin-1 and Orexin-A in adults with obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Life (Basel) 13(1), 245 (2023).

Bassetti, C. L. Sleep and stroke. Semin Neurol. 25, 19–32 (2005).

Vazir, A. & Kapelios, C. J. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: who and why to test and how to intervene? Heart. (2023).

Mosli, H. H., Kutbi, H. A., Alhasan, A. H. & Mosli, R. H. Understanding the interrelationship between Education, Income, and obesity among adults in Saudi Arabia. Obes. Facts. 13, 77–85 (2020).

Zheng, X. et al. The association between health-promoting-lifestyles, and socioeconomic, family relationships, social support, health-related quality of life among older adults in China: a cross sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 20, 64 (2022).

Zhang, Q. N. & Lu, H. X. Knowledge, attitude, practice and factors that influence the awareness of college students with regards to breast cancer. World J. Clin. Cases. 10, 538–546 (2022).

Chatterjee, S. et al. Diabetes structured self-management education programmes: a narrative review and current innovations. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 6, 130–142 (2018).

Kuwabara, A., Su, S. & Krauss, J. Utilizing Digital Health Technologies for Patient Education in Lifestyle Medicine. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 14, 137–142 (2020).

Seymour, J. The Impact of Public Health Awareness Campaigns on the awareness and quality of Palliative Care. J. Palliat. Med. 21, S30–s6 (2018).

Kim, J. M. et al. Evaluation of patient and Family Engagement Strategies to improve Medication Safety. Patient. 11, 193–206 (2018).

AlRuthia, Y. et al. The relationship between Health-Related Quality of Life and Trust in Primary Care Physicians among patients with diabetes. Clin. Epidemiol. 12, 143–151 (2020).

Baghri Lankaran, K. & Ghahramani, S. Social studies in health: a must for today. Med. J. Islam Repub. Iran. 32, 106 (2018).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (Guilford, 2023).

Funding

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation Youth Fund Project (82200548).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

(I) Conception and design: Fuchao Yu, Qiang Zhang, Qin Wei, Jiayi Tong.(II) Administrative support: Fangping Zhou, Liang Xie, Wu Cao, Qing Hao.(III) Provision of study materials or patients: Xuan Xu, Penghao Zhen, Songsong Song, Zhuyuan Liu, Sifan Song, Shengnan Li, Min Zhong, Runqian Li, Yanyi Tan.(IV) Collection and assembly of data: Fuchao Yu, Fangping Zhou(V) Data analysis and interpretation: Fuchao Yu, Xuan Xu, Penghao Zhen(VI) Manuscript writing: All authors(VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical statement

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Zhongda Hospital Affiliated to Southeast University (2020ZDSYLL278-P01) and obtained informed consent from all participants.All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, F., Zhou, F., Hao, Q. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of inpatients with cardiovascular disease regarding obstructive sleep apnea. Sci Rep 14, 25905 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77546-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77546-9