Abstract

This study presents the design and analysis of a high-performance metamaterial absorber for the optical terahertz (THz) regime. The proposed absorber utilizes a unique nested flower-shaped structure composed of nickel (Ni) and silicon dioxide (SiO2), achieving an average absorption exceeding 97.91% with a broad bandwidth of 1320 THz (180 THz − 1500 THz). A unit cell size of 66 nm × 66 nm × 24 nm makes this design highly attractive for miniaturized devices. Strong absorption originates from localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), where light interacts with the electrons on the Ni surface. Notably, the design maintains excellent absorption performance even at oblique incident angles up to 60° with polarization insensitivity. These results highlight the Ultra-Compact Plasmonic Metamaterial (UCPM) absorber’s potential for diverse applications due to its broad spectral response, high absorption efficiency, and minimal footprint, making it valuable for energy harvesting, infrared imaging, and electromagnetic stealth technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Emerging from the field of metamaterials, a class of artificially engineered materials, lies a burgeoning area of research with significant implications for sustainability. These materials exhibit a remarkable range of properties dependent on their design, offering exciting possibilities in energy capture, stealth, and sensing applications. Particularly noteworthy are metamaterial absorbers (MAs), first described by Landy et al.1. MAs leverage their unique electromagnetic properties, including negative permeability and permittivity, to manipulate light at sub-wavelength dimensions. This capability has fueled extensive exploration for applications in diverse fields like solar energy harvesting, wireless communication, and sensors2,3,4. Among these applications, metamaterial perfect absorbers (MPAs) have garnered particular attention due to their wide-ranging potential in optoelectronics, spanning photovoltaics, solar cells, thermal radiation, and material detection. The inherent adaptability of MPAs highlights their potential to revolutionize optoelectronic technologies and unlock a plethora of practical applications. Research efforts are currently focused on optimizing key characteristics of these absorbers, such as absorption efficiency, tunability, and unit cell size, paving the way for their future implementation2,3,4.

Achieving broad absorption bandwidths in metamaterial absorbers is a key research focus. A prominent approach utilizes the metal-insulator-metal (MIM) configuration, a well-established triple-layer structure proven highly effective in plasmonic absorbers5,6. MIM-based designs typically feature uniformly distributed top resonators separated by a thin dielectric spacer. This spacer critically facilitates strong plasmonic coupling between the top resonators and the underlying metal film. In essence, the entire absorber structure functions as a resonator with a single input transmission line. Optimizing the dimensional parameters and shaping the top metallic layer of this MIM-based resonator remain the primary strategies for maximizing both the intensity and bandwidth of absorption in MAs.

Prior research has demonstrated successful designs for broadband light absorption using various geometries, achieving near-perfect absorption across wide ranges in the visible and near-infrared spectrum e.g., triangular prisms7, double-sized axe resonators8, nanodisk designs9. Lai et al.‘s tri-layered Al-SiO2 design achieved high average absorptivity (450–600 nm) within the visible spectrum10. Building on MIM configurations, Sultan et al.‘s star-shaped resonator design offered broader visible range absorption (389–697 nm) with good angular stability11. Li et al.‘s deep-subwavelength meander line antenna design achieved high infrared absorption (11–14 μm) with a compact footprint12. Plasmonic metamaterial absorbers (PMAs) achieve novel spectral absorption through synergistic effects. These absorbers harness the strong interaction between plasmon resonances and phonon vibrations within the material and material losses occurring within the dielectric spacer further contribute to absorption. The LSPR is the fundamental physical phenomenon that drives the enhanced absorption characteristics in the metamaterials absorbers. PMAs, essentially arrays of subwavelength metallic nanostructures, act as optical antennas, effectively concentrating and propagating light into regions much smaller than the wavelength. This concentrated light is then efficiently converted into heat through the LSPR phenomenon13,14,15. Bilal et al.‘s ultrathin tungsten nanowire absorber demonstrates the potential of this approach, achieving over 80% absorption across a significant bandwidth (400–750 nm)16. However, the quest continues for even broader absorption.

The ideal design would be a thin, broadband absorber exhibiting near-perfect absorption with minimal sensitivity to the angle of light incidence. This study unveils a novel metamaterial absorber designed for ultrahigh absorption across the entire optical spectrum. The design leverages a unique MIM configuration with a captivating flower-shaped top layer. The key innovation lies in the meticulously arranged, concentric flower-shaped rings surrounding a central flower. This precise control over the unit cell geometry, achieved through ring size and spacing optimization, is crucial for achieving near-perfect, broadband absorption.

The paper adopts a meticulous organizational structure. It commences by introducing a groundbreaking flower-shaped metamaterial absorber design, emphasizing its exceptional broad spectral absorption encompassing the entire optical spectrum. Subsequently, the work delves into the fundamental mechanism governing this remarkable light capture phenomenon. The focus then shifts towards the meticulously designed optimization process for the absorber’s geometry, aiming to achieve maximum absorption efficiency. To gain a deeper understanding of the light-trapping mechanism, the paper presents a detailed analysis of the field distributions and surface current densities within the structure. Furthermore, the work explores the absorber’s performance under a comprehensive range of parametric studies. These studies encompass the impact of incident angle, polarization angle, variations in structural parameters, and even the utilization of different material combinations for the metal-insulator-metal layers. Following these in-depth analyses, the paper presents a comparative assessment, meticulously evaluating the proposed design against recent advancements within the field. Finally, the work concludes by highlighting the significance of this design as an ultrathin, ultra-wideband absorber with promising applications across various disciplines.

Proposed absorber design

This section meticulously dissects the unit cell structure of the Ultra-Compact Plasmonic Metamaterial (UCPM) absorber. The UCPM adopts a metal-dielectric-metal (MDM) configuration, meticulously crafted using three distinct layers. This article begins with a comprehensive exploration of the unit cell design, including the material selection, dimensional parameters, and the unique flower-shaped geometry. This analysis delves into the underlying absorption mechanism responsible for the UCPM’s exceptional performance. Subsequently, the section explores the development of equivalent circuit models to represent the electrical behavior of the absorber.

Material, dimensions, and configuration

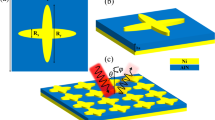

Figure 1 presents a schematic illustration of the proposed plasmonic metamaterial absorber’s unit cell design. The design adopts a classic Metal-Insulator-Metal (MIM) configuration, featuring three distinct layers. The top and bottom layers consist of thin metallic films made of nickel (Ni). Nickel possesses a high electrical conductivity of 1.43 × 10^7 S/m, ideal for efficient light absorption. These metallic layers sandwich a middle insulating layer composed of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Silicon dioxide, with a permittivity of 2.25, serves as a spacer layer and plays a critical role in controlling the light interaction within the structure. The periodicity, denoted by ‘p’ nm, represents the repeating pattern of the unit cell across the entire metamaterial absorber.

The metamaterial is designed by depositing the metallic layers above and beneath the substrate of silicon dioxide (SiO2) with optimum thicknesses. The top layer of Ni has multiple rings farming a nested flower-shaped structure with a thickness of “t1”. The width of each ring and spacing between the two rings are taken to be “b”. At the middle of the arrangement, the SiO2 base, a square-shaped of thickness “t2”. The bottom square-shaped metallic layer of Ni has a thickness of “t3”. The proposed absorber exhibits resonance in the visible light spectrum and expands the band in full optical radiation. The proposed plasmonic metamaterial absorber’s unit cell periodic configuration is illustrated in Fig. 1a. Figure 1b–d show the proposed absorber’s frontal, side, and bottom perspectives. Table 1 represents the optimal dimension of the proposed plasmonic metamaterial absorber considering getting an average absorption of greater than 90% in the entire optical radiation spectrum. The width of each ring and the gap between two rings in the nested flower structure are to be kept as b = 2.5 nm.

Absorption mechanism

Absorption of electromagnetic waves is determined by what remains within the absorber structure after the wave undergoes reflection and transmission. This principle can be briefly expressed as Eq. (1)17,18. The reflection coefficient encompasses both co-polarized and cross-polarized components. The co-polarized component arises when both incident and reflected electromagnetic waves exhibit either TE or TM polarization. Conversely, the cross-polarized component emerges when the incident wave is TE-polarized and the reflected wave is TM-polarized, or vice versa.

where A(f), R(f), and T(f) are the absolute values of absorption, reflected, and transmitted powers respectively in the operating frequency bands. When the transmitted and reflected powers reach zero, the absorption becomes unity. In this situation, electromagnetic waves are perfectly absorbed. As mentioned in Eq. (1) the reflected power \(R\left(f\right)={\left|{S}_{11}\left(f\right)\right|}^{2}\) and \(T\left(f\right)={\left|{S}_{21}\left(f\right)\right|}^{2}\). To reduce the reflected power R(f), S11(f) should be minimized, which can be achieved by matching the impedances between the absorber and the environment. By putting the bottom metallic layer as a full ground geometry, the transmission coefficients S21(f) go toward zero as a result transmitted power is also nullified.

By this arrangement, the electromagnetic wave cannot pass through the bottom metallic layer reflected inside the structure and remain absorbed by the structures at all. As a result, transmission becomes null, and thus the absorption is then represented by the Eq. (2)1,19.

The proposed structure is simulated in electromagnetic simulation tool, HFSS and it is validated using CST Microwave Studio. The reflection and absorption of this Ultra-Compact Plasmonic Metamaterial (UCPM) absorber are presented in Fig. 2a,b respectively. A reflection coefficient is less than − 10dB and an average absorption rate of over 97% for a frequency range of 180 THz to 1500 THz by HFSS, encompasses the optical radiation window comprised of UV, Visible light, and IR range of frequencies.

Design and performance analysis

In this section first, discuss the design parameters and design steps that are involved in finding out the final structure of the proposed NSS-PMA then show the impact of variation in incident angle and polarization angles on the absorption results. This section also provides E-field, H-field, and Current distribution related to the absorber geometry and their effect on absorption.

Optimizing unit cell geometry

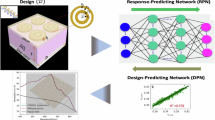

The absorber’s design evaluations have been detailed to assess the effectiveness of each proposed configuration in terms of absorption. Figure 3 illustrates six distinct designs to obtain the optimal design of the Ultra-Compact Plasmonic Metamaterial (UCPM) absorber. Design-1, depicted in Fig. 3a, features a single flower-shaped resonator positioned atop the insulating layer. In design-2, shown in Fig. 3b, an additional circular flower-shaped ring is incorporated into design-1. Design-3, represented by Fig. 3c, introduces two flower-shaped rings to the structure of design-1. Subsequently, further structures are developed by adding more rings to the initial design-1. These are presented as design-4, design-5, and design-6 in Fig. 3d–f respectively. The reflection and absorption characteristics corresponding to each design are illustrated in Fig. 4a.,b.

The reflection and absorption characteristics corresponding to each design are presented in Fig. 3a–e is illustrated in Fig. 4a,b respectively. Tables 2 and 3 represent the performance of different designs. Table 2 gives the findings from the reflection coefficient curve of different designs aimed at achieving the final structure. Each design, labeled from Design-1 to Design-6 with varying numbers of rings added to a flower-like structure. The investigation into flower antenna designs demonstrates a noteworthy trend. As the number of rings increases, the operational bandwidth widens, and the minimum S11 value initially improves. However, adding rings beyond Design 4 exhibits a detrimental effect, causing the S11 value to degrade. This highlights the effectiveness of the proposed design (Design 5), which achieves the superior combination of the broadest bandwidth and a significantly improved minimum S11 value at a favorable resonant frequency of 670 THz.

On the other hand, Table 3 represents the performance based on the absorption characteristics corresponding to each design structure. The table outlines observations of absorption characteristics curve for various designs, aiming to identify the final structure’s optimal performance. Each design, ranging from Design-1 to Design-6 with incremental additions of rings to a flower-like structure, exhibits distinct bandwidths for absorption exceeding 95%, along with percentage average absorption and peak absorption frequency points in THz. Notably, the evolution from Design-1 to Design-2, incorporating additional rings, demonstrates an expansion in bandwidth and an enhancement in both percentage average absorption and peak absorption frequency point, culminating in the Proposed Design. This design showcases the broadest absorption bandwidth, the highest percentage average absorption, and a peak absorption frequency point of 670 THz, indicating superior absorption characteristics suitable for the intended application.

E & H-field distribution and current density analysis

This section meticulously analyzes the electric (E), magnetic (H) field, and surface current density distributions within the UCPM absorber (Figs. 5, 6, 7) to gain deeper insight into its light absorption mechanisms. Scrutinizing these distributions helps elucidate how the design effectively captures and dissipates incident electromagnetic waves.

In this configuration, the electric field (E) aligns horizontally, while the magnetic field (H) aligns vertically. At the resonant frequency of 670 THz, the nested flower rings exhibit notable charge redistribution, with charges accumulating on the upper and lower sides as shown in Fig. 5a,b. This phenomenon induces an electrical dipole resonance within the rings, fostering strong coupling with the underlying structure. The proposed design leverages a synergistic interaction of electric and magnetic resonances to achieve efficient light absorption. At the resonant frequency (670 THz), the nested flower rings exhibit a distinct electric dipole resonance due to prominent charge redistribution (Fig. 5a,b). This phenomenon fosters strong coupling with the underlying structure.

Additionally, a concentrated magnetic field distribution resides primarily within the intermediate dielectric layer, induced by the magnetic resonance (Fig. 6). The accumulation of opposite charges on the flower ring structures leads to the formation of reverse currents on the top and bottom metal layers. This current flow generates a magnetic dipole resonance within the absorber. The surface current density at the interface between the metal layers and the dielectric spacer directly influences the magnitude of these reversed currents and the resulting magnetic resonance. A higher surface current density signifies a greater current concentration, leading to a stronger magnetic response and a more pronounced resonance effect as represented in Fig. 7a,b. In essence, the interplay between electric and magnetic resonances, coupled with the influence of surface current density, facilitates the effective absorption of incident electromagnetic wave energy within the intermediate dielectric layer.

Effect of incident and polarization angles variation on the absorber performance

The proposed absorber demonstrates remarkable resilience to variations in incident angles. As shown in Fig. 8a, the reflection coefficient S11 remains below − 10 dB (indicating low reflection loss) for incident angles up to 50°. Beyond 50°, the S11 increases, suggesting a decrease in absorption. Moreover, the absorber exhibits excellent polarization insensitivity as represented in Fig. 8b. Regardless of the TE wave’s polarization angle (the angle between the electric field vector and the X-axis), the reflection coefficient spectrum remains consistent. This confirms the absorber’s robust performance under various polarization conditions.

Effects of different structural parameters

Subsequently, the investigation delved into the influence of various structural parameters on the absorption capabilities of the Ultra-Compact Plasmonic Metamaterial (UCPM) absorber. Specifically, scrutinized the impact of altering the thickness (t1) of the top metallic layer on the absorber’s reflection coefficient, thereby gauging its effect on absorption efficiency, as illustrated in Fig. 9a and Table 4. To elucidate this relationship, this work systematically increased the thickness of t1 from 3 nm to 11 nm in increments of 2 nm, while maintaining a constant height for the dielectric layer at t2 = 12 nm. Upon careful examination of the reflection characteristic curves for these variations, a significant observation was made. Each thickness shows a dip or resonance at different frequencies, where the reflection is minimized (the material is more absorptive). Thicker layers tend to shift the resonant frequencies towards lower values, and the sharpness of the resonance also changes. The curve for t1 = 5 nm shows the lowest S11 value (most negative), indicating the best impedance match around 670 THz. This phenomenon indicates that minimizing reflection leads to maximal absorption efficiency. This article explored the impact of varying t2 (thickness of substrate layer) from 6 nm to 18 nm in 3 nm increments, while holding t1 constant at 5 nm. Our analysis focused on observing the reflection characteristic curves for these different heights, intending to identify minimum value of S11 (dB) and the frequency range wherein the reflection coefficient remained below − 10dB. Notably, our findings, as depicted in Fig. 9b and Table 5, highlight the optimal performance achieved when t2 was set to 12 nm, characterized by the most favorable combination of dips and bandwidth.

The thickness of a material plays a crucial role in determining its wave impedance, which in turn affects the reflection of electromagnetic waves when they encounter different materials. When a wave travels through a medium and reaches the boundary between two materials, part of the wave may be reflected, while another part may be transmitted. The reflection is affected by the impedance mismatch between the materials and the thickness of the second material layer. Each material has a characteristic wave impedance {\({Z}_{e}\left(\text{f}\right)\)}, which is determined by its electrical properties, such as effective permittivity{\({{\upepsilon}}_{eff}\left(\text{f}\right)\}\), and effective permeability \({\{{\upmu}}_{eff}\left(f\right)\}\)20,21. This characteristic wave impedance {\({Z}_{e}\left(\text{f}\right)\}\), can be expressed by Eq. (3) as:

The effective refractive index {\({{\upeta}}_{eff}\left(\text{f}\right)\)} can be related with effective permittivity \({\{{\upepsilon}}_{eff}\left(\text{f}\right)\}\), and effective permeability \({\{{\upmu}}_{eff}\left(f\right)\}\) as by Eqs. (4) and (5) respectively as:

Whereas the effective refractive index ηeff can be represented as per Eq. (6) When, f = frequency of operation; \(C\) = velocity of light; La is transmission length (height of the metamaterial absorber structure).

The environmental impedance (Z0 ≈ 377 Ω) should be matched with the absorber’s effective characteristic wave impedance for perfect absorption. The reflection coefficient S11 (dB) and transmission coefficient S21 (dB) can be used to characterize the characteristic wave impedance \(\left\{{Z}_{e}\left(\text{f}\right)\right\}\), of the absorber as Eq. (7).

The material’s thickness influences the wave’s phase after it travels through the material. Depending on the thickness of the material relative to the wavelength of the wave inside the material, constructive or destructive interference can occur between the incident and reflected waves, significantly affecting the overall reflection. The effect of material thickness comes into play because the wave may travel through the material and experience multiple internal reflections. These reflections can interfere either constructively or destructively, depending on the path length (related to thickness) and wavelength. The bottom and top metals generate capacitance with the help of a dielectric layer. The capacitance of the structure depends strongly on the dielectric thickness and is inversely proportional to the dielectric thickness. As the thickness increases, the capacitance decreases; thus the absorption bandwidth moves linearly from left to right. Also, the dielectric layer confined most of the wave within it and made a structure highly procurable for absorption.

Material selection for metal and insulator

The material selection for metal and insulators is characterized by calculating S11 parameters with different combinations of metal and insulator layers. Firstly, to optimal choice of metallic layer, the proposed absorber structure is designed and simulated with different combinations of metallic layer with SiO2 insulating layer. The S11 characteristics as depicted in Fig. 10a, show a minimum value of S11 (dB) < -38 dB and less than − 10dB for a full optical radiation spectrum with a Ni metallic layer. Correspondingly maximum absorption is achieved for this metal and insulators a result gives the optimum choice of metallic layer as Ni. For the optimal choice of insulating layer, the proposed absorber structure is designed with the different insulating layers with a Ni metallic layer. The S11 characteristics for the different insulating layers are depicted in Fig. 10b, showing a minimum value of S11 (dB) <-38 dB and having less than − 10dB for a full optical radiation spectrum with SiO2 insulating layer. Correspondingly maximum absorption is achieved for this metal and insulators a result gives the optimum choice of metallic layer as Ni.

Tables 6 and 7 present the electromagnetic and optical properties of various metals and dielectrics, respectively. Among the metals in Table 6, Nickel (Ni) exhibits exceptionally high permeability, resulting in greater absorption compared to other metallic layers within the optical radiation range. Similarly, in Table 7, silicon dioxide (SiO2) shows low permittivity, contributing to broad absorption and high transparency in the optical radiation spectrum.

Comparative analysis

In this section, the comparative analysis of this work is done with recently published works operating in the optical radiation regime to show that this work outperforms the others. Table 8 summarizes the comparative analysis of the proposed work with various absorbers in the optical regime. Existing absorbers19,20,21,22,23 typically utilize materials like Titanium (Ti) or Tungsten (W) and achieve high average absorption (over 90%) across a range of terahertz frequencies. However, their unit cell sizes are relatively large (ranging from 225 nm to 750 nm). The proposed work explores a Nickel (Ni) based metamaterial with a significantly smaller unit cell size (66 nm) while maintaining high average absorption (97.91%) across a broad bandwidth (1320 THz). This suggests the proposed design offers a promising route for creating high-performance terahertz metamaterial absorbers with a more compact design. This combination of a compact structure, extensive bandwidth, and high absorption efficiency demonstrates the superior performance and potential application advantages of the proposed work over the other designs listed.

Conclusion

This work presented a novel ultra-compact plasmonic metamaterial (UCPM) absorber designed for the terahertz regime. The UCPM exhibits exceptional light absorption characteristics, achieving a maximum of 99.99% and maintaining an average above 97.91% throughout the operating range (180 THz − 1500 THz). Furthermore, the design offers remarkable resilience to both polarization and incident angles in TE and TM modes. The paper delves into the underlying absorption mechanism by analyzing surface current distributions, electric and magnetic field profiles, and the metamaterial’s properties. The design process, material selection, and the impact of parameter variations are also comprehensively explored. The proposed UCPM boasts significant advantages such as flexibility, polarization insensitivity, and stable absorption under oblique angles, making it highly suitable for diverse applications. These include advancements in avionics stealth technology and energy harvesting for low-power Internet of Things (IoT) devices, due to its compact design and efficient terahertz wave absorption within a flexible structure.

Data availability

The authors confirm that data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article. Software Used to Create the Map in the Figures: S-I—Ansys HFSS-15 3D High-Frequency Structure Simulation Software. S-II—MATLAB R2020. S-III—CST Microwave Studio.

References

Landy, N. I., Sajuyigbe, S., Mock, J. J., Smith, D. R. & Padilla, W. J. Perfect metamaterial absorber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100(20). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.207402 (2008).

Park, J. W. et al. Multi-band metamaterial absorber based on the arrangement of donut-type resonators. Opt. Express 21(8), 9691. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.21.009691 (2013).

Song, S., Chen, Q., Jin, L. & Sun, F. Great light absorption enhancement in a graphene photodetector integrated with a metamaterial perfect absorber. Nanoscale. 5 (20), 9615–9619. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3nr03505k (2013).

Ducournau, G. et al. THz communications using photonics and electronic devices: The race to data-rate. J. Infrared Millim. Terahertz Waves 36(2), 198–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10762-014-0112-x (2015).

Charola, S. et al. Numerical investigation of wideband L-shaped metasurface based solar absorber for visible and ultraviolet region. Phys. B Condens. Matter 601(August 2020), 412503 (2021).

Elrashidi, A. & Tharwat, M. M. Broadband absorber using ultra-thin plasmonic metamaterials nanostructure in the visible and near-infrared regions. Opt. Quant. Electron. 53(8). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-021-03089-2 (2021).

Zhou, J. et al. Ultra-broadband solar absorbers for high-efficiency thermophotovoltaics. Opt. Express. 28, 36476. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.411918 (2020).

Tuan, T. S. & Hoa, N. T. Q. Numerical study of an efficient broadband metamaterial absorber in visible light region. IEEE Photonics J. 11(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPHOT.2019.2910806 (2019).

Aalizadeh, A. E. et al. A route to unusually broadband plasmonic absorption spanning from visible to mid-infrared. Plasmonics 141, 1269–1281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11468-019-00916-x (2019).

Lai, Y. C., Chen, C. Y., Hung, Y. T. & Chen, C. Y. Extending absorption edge through the hybrid resonator-based absorber with wideband and near-perfect absorption in visible region. Materials (Basel). 13(6), 1470(1–8). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13061470 (2020).

Mahmud, S. et al. Design and parametric analysis of a wide-angle polarization-insensitive metamaterial absorber with a star shape resonator for optical wavelength applications. Results Phys. 18, 103259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2020.103259 (2020).

Li, J. et al. Plasmonic metamaterial absorbers with strong coupling effects for small pixel infrared detectors. Opt. Express 29, 22907. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.430156 (2021).

Wu, P., Zhang, C., Tang, Y., Liu, B. & Lv, L. A perfect absorber based on similar fabry-perot four-band in the visible range. Nanomaterials 10(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10030488 (2020).

Zhang, M. et al. A nano-micro engineering nanofiber for electromagnetic absorber, green shielding and sensor. Nano-Micro Lett. 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00552-9 (2021).

Xu, R. et al. A review of broadband low-cost and high-gain low-terahertz antennas for wireless communications applications. IEEE Access 8, 57615–57629. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2981393 (2020).

Bilal, R. M. H. et al. Ultrathin broadband metasurface-based absorber comprised of tungsten nanowires. Results Phys. 19, 103471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2020.103471 (2020).

Tao, H. et al. A metamaterial absorber for the terahertz regime: Design, fabrication and characterization. Opt. Express 16(10), 7181. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.16.007181 (2008).

Raeen, M. S., Nella, A. & Rajagopal, M. A fourfold star petal–shaped polarization–insensitive broadband.pdf. Plasmonics 18(2), 1059–1074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11468-023-01815-yA (2023).

Raeen, M. S. & Nella, A. Aplasmonic metamaterial flexible absorber design and analysis in optical regime. Opt. Quantum Electron. 55(8), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-023-04968-6 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Robust method to retrieve the constitutive effective parameters of metamaterials. Phys. Rev. E 70(1), 016608 (2004).

Al-badri, K. S. et al. Simulated and experimental verification of the microwave dual-band metamaterial perfect absorber based on square patch with a 450 diagonal slot structure. J. Electromagn. Waves Appl. 35(11), 1541–1552 (2021).

Ordal, M. A. et al. Optical properties of the metals Al Co, Cu, Au, Fe, Pb, Ni, Pd, Pt, Ag, Ti, and W in the infrared and far infrared. Appl. Opt. 22(7), 1099–1119 (1983).

Rumble, J. (ed) CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (2017).

Liang, D. et al. Metamaterial absorber with broadband and superior absorption realized by optical nanotrapping hybrid cavity. Opt. Laser Technol. 177, 111007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2024.111007 (2024).

Sayed, S. I., Mahmoud, K. R. & Mubarak, R. I. Strong and broadband visible absorption based on titanium patterned resonator. Plasmonics 1145–1152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11468-023-02068-5 (2023).

Musa, A. et al. Broadband plasmonic metamaterial optical absorber for the visible to near-infrared region. Nanomaterials. 13(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13040626 (2023).

Wu, D., Lei, L., Xie, M., Xu, P. & Xu, S. High-performance metamaterial light absorption from visible to near-infrared assisted by anti-reflection coating. Photonics 10(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics10090998 (2023).

Sayed, S. I., Mahmoud, K. R. & Mubarak, R. I. Design and optimization of broadband metamaterial absorber based on manganese for visible applications. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38263-x (2023).

Funding

This work is funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia under Grant No. RG-46-135-42.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M S R: Data curation, Writing - Original draft preparation, Software, Validation, Visualization, Formal analysis. A N: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration.R W A: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This declaration is not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raeen, M.S., Nella, A. & Aldhaheri, R.W. A high-performance ultra-compact plasmonic metamaterial structure for optical THz absorption. Sci Rep 14, 27203 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77898-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77898-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Metamaterial absorber using cascaded ring resonators and optimization through machine learning for sensing applications

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Design and optimization of a graphene-based broadband absorber for enhanced absorption in the visible and near-infrared spectrum

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2025)