Abstract

Oral frailty (OF) is a form of frailty. Laughter and social communication such as talking and participating in community activities, contribute to extending healthy life expectancy by reducing stress and increasing physical activity. However, limited research exists on the association between laughter and social communication and OF. This cross-sectional study aimed to explore the association of laughter and social communication with the risk of developing OF using the eight-item OF Index among Fukushima residents. In 2020–2021, 916 residents aged 60–79 were surveyed regarding OF and psychosocial factors. Binomial logistic regression analysis was performed to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for psychosocial factors associated with the OF prevalence. The OF prevalence was 41.5%. The sex- and age-adjusted ORs (95% CIs) for psychosocial factors associated with OF prevalence were 0.38 (0.26–0.57) for daily laughter, 0.51 (0.35–0.76) for laughter 1–5 times/week, 0.42 (0.20–0.89) for daily talking, 0.40 (0.22–0.72) for participating in community activities more than once/week, and 0.29 (0.20–0.43) for no depressive symptoms. After multivariate adjustment, only daily laughter and no depressive symptoms were associated with OF. As a public health strategy, increasing laughter and social communication frequencies, along with reducing depressive symptoms, may enhance healthy life expectancy through improved frailty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In Japan, the proportion of people aged ≥ 65 years is approximately 29.2%1, and this proportion is expected to increase further2. With the increasing life expectancy and the aging population in developed countries, the incidence of frailty is estimated at 43.4 new cases per 1,000 person-years3. Frailty is defined as a transition from healthy aging to disability4,5. In Japan, a super-aging society with an aging population rate exceeding 21%, the impact of frailty on physical, mental, and social well-being poses significant challenges, including increased medical costs, dementia, and a growing need for care6. Additionally, the association between poor oral function and frailty7,8 as well as between the number of remaining teeth and mortality9,10 makes maintaining oral health crucial for extending healthy life expectancy. Oral health has been reported as a potential predictor of physical frailty (PF) and a marker of deteriorating oral health status11. In 2014, the term “oral frailty” (OF) was proposed by the Japan Dental Association to describe a series of negative processes resulting from changes in aging-related oral conditions (e.g., number of teeth, oral hygiene, and oral function), reduced interest in oral health, and diminished physical and mental reserve capacity12,13. These changes increase oral vulnerability and can lead to eating dysfunction, further influencing PF and causing a decline in physical and mental function. A longitudinal study of approximately 2000 older adults in Kashiwa showed that individuals with OF had more than twice the incidence of PF, sarcopenia, care needs, and mortality compared with those without OF14, indicating the role of OF in these issues. Despite its significance, no established method exists for evaluating OF15. In Japan, the most commonly used criteria to assess OF include (1) poor oral hygiene (oral uncleanliness), (2) xerostomia, (3) poor bite strength, (4) poor lingual-lip motor function, (5) low tongue pressure, (6) poor masticatory function, and (7) poor swallowing function16. However, some of these parameters require specialized training and dental equipment for evaluation. Nevertheless, simple questionnaires have been developed. The eight-item OF Index (OFI-8), developed by Tanaka et al. and endorsed by the Japanese Dental Association, objectively reflects oral function through dentist-conducted oral examinations17. Such a straightforward questionnaire proves valuable for easily evaluating the risk of developing OF during health checkups and nondental outpatient settings.

Recently, factors such as social communication—meeting with friends and participating in social activities—along with the absence of depression, exercise, and nutrition interventions, have been reported to be associated with the prevention of frailty18,19,20,21. Recent studies indicate that laughter may play a role in preventing the onset and severity of lifestyle-related diseases by reducing the physical symptoms of stress22,23,24,25. A large prospective study found that enjoying life reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease-related mortality26. Furthermore, a cross-sectional study reported that individuals who laugh less have a higher risk of heart disease compared with those who laugh more27. These findings suggest that laughter and social communication may be linked to extended life expectancy and healthy life expectancy. While previous studies have suggested a potential relationship between laughter, social communication, and health outcomes, the specific impact on oral health has been underexplored. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the association of laughter and social communication with the prevalence of OF by conducting a cross-sectional questionnaire survey using the OFI-8 among residents of Fukushima Prefecture. The findings of this study may be valuable for enhancing our understanding of and addressing OF and PF, thereby contributing to increased healthy life expectancy.

Methods

Study design, setting, and participants

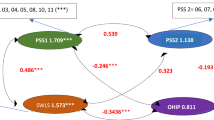

In this cross-sectional study, a physical function test and questionnaire survey were conducted during Naraha Town’s health checkups in 2020 and 2021 among 1717 residents aged 60–79 years. Participants were enrolled based on their residence in Naraha Town, age (60–79 years at the time of the health checkup), and willingness to participate in the study. Additionally, individuals whose OF status could not be determined due to incomplete answers to the OFI-8 questions were excluded. Considering the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic28 on health examination participation, the survey period was set for 2 years, from September 1 to September 6, 2020, and from September 6 to September 13, 2021. For participants who attended both checkups, data from the 2020 assessment were used. Duplicates were excluded. Ultimately, the data of 916 participants were analyzed (Fig. 1).

This study complied with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the Fukushima Medical University Ethics Committee (approval number 29143). A questionnaire was mailed to the residents by the town 2–3 weeks before the health checkup, along with an explanation of the study’s purpose, and the questionnaire was collected during the examination. By submitting the questionnaire at the checkup, participants provided written informed consent to participate. The questionnaires were checked for missing entries by university staff.

Measurements

OF

OFI-817 was used to classify participants’ OF status. It comprises the following eight questions: (1) Do you have any difficulties eating tough foods compared with 6 months ago? (2) Have you choked on your tea or soup recently? (3) Do you use dentures? (4) Do you often have a dry mouth? (5) Do you go out less frequently than you did last year? (6) Can you eat hard foods like squid jerky or pickled radish? (7) How many times do you brush your teeth in a day (≥ 2 times/day)? and (8) Do you visit a dental clinic at least annually?

The score gives double weight to the three most critical component questions (questions 1–3). Specifically, if participants answered “yes” to questions 1–3, 2 points were given for each response. If participants answered “yes” to questions 4–8, 1 point was given for each response17. The total OFI-8 score ranges from 0 to 11 points, with 0–2 points classified as oral robust (ORO), 3 points as oral prefrailty (OPF), and ≥ 4 points as OF17. To determine the frequency of daily tooth brushing, participants were asked if they brush their teeth daily (yes/no). The timing of tooth brushing was reported with options: upon waking, after breakfast, after lunch, after dinner, before bed, or others. Tooth brushing frequency was categorized into two groups based on whether participants brushed their teeth at least twice a day.

PF

PF was assessed using the Japanese version of the Cardiovascular Health Study criteria (J-CHS criteria) developed by Fried et al.29,30 The J-CHS includes five items: (1) weight loss, (2) feeling tired, (3) no physical activity, (4) walking speed (≤ 1.0 m/s), and (5) grip strength (< 28 kg in men and < 18 kg in women). Each item is scored 1 point. The total score ranges from 0 to 5 points, with 0 points classified as robust, 1–2 points as prefrailty (PPF), and 3–5 points as PF. Physical activity was scored based on whether both regular and light exercise were performed once a week or less. Walking speed and grip strength were measured by trained university staff. Grip strength was measured twice for each hand using a Takei handgrip dynamometer (Takei Scientific Instruments Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and the maximum value was used to determine PF. To identify participants who were immobile, the maximum walking speed was used instead of normal walking speed to determine PF, as normal walking speed is less likely to change with exercise intervention31.

Laughter and social communication

Based on our previous studies27,32, daily laughter frequency was assessed by asking the question, “How often do you laugh out loud?” Response options included “almost every day/1–5 days per week/1–3 days per month/almost never.” Similarly, the frequency of daily talking with others was assessed using the same response options. Additionally, the frequency of participation in community activities was evaluated with response options of “almost every day/1–5 days per week/1–3 days per month/almost never/never.”

Lifestyle factors and other confounding factors

Lifestyle factors were collected for the following: smoking status (never/past/current) and current drinking habits (never/occasional/almost daily). Physical activity was classified as regular and light exercise, either light or regular exercise, or no exercise. Additionally, potential confounders such as sex (men/women), age, body mass index, depressive symptoms, and history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), and dyslipidemia (no/yes) were collected. Depressive symptoms were evaluated using two questions based on the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders Procedure33 developed and validated for screening mental disorders: (1) “During the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?” and (2) “During the past month, have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?” Participants answering “yes” to both questions were considered to have depressive symptoms, those answering “no” to both were considered to have no depressive symptoms, and others were classified as having depressive tendencies34.

Statistical analysis

Regarding the basic characteristics, the variables for OF, laughter, social communication, and lifestyle factors were presented as categorical variables (frequency and proportion) and continuous variables (mean and standard deviation). Odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using binomial logistic regression models to compare the group with OF versus the group without OF (ORO + OPF). The factors analyzed included sex, age, PF or PPF, depressive symptoms, frequencies of laughter, talking, and participation in community activities, as well as history of hypertension and DM, smoking and drinking habits, and physical activity. Two multivariate-adjusted models were used: Model 1 was adjusted for sex and age, whereas Model 2 was adjusted for sex, age, PF, and history of hypertension, DM, and lifestyle factors. These adjustment variables were selected based on factors previously reported to be related to frailty35,36,37. Stratified analyses were performed for each sex and age category, as sex and age may have interactive effects. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the participants and prevalence of OF

The participants’ characteristics and OF status by sex and age category are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 68.4 years (67.3 years for those with ORO, 68.7 years for those with OPF, and 69.3 years for those with OF). The prevalence of OPF was 18.2%, slightly higher among women and those in their 70s. The prevalence of OF was 41.5%, also higher among individuals in their 70s.

Multivariate adjustment analysis for the prevalence of OF on laughter and social communication

Table 2 shows the ORs and 95% CIs for each factor considered in the multivariate models (Models 1 and 2) using logistic regression analysis for the prevalence of OF, with the reference group being those without OF (ORO + OPF).

After adjustment for sex and age (Model 1), the following factors were significantly associated with the prevalence of OF: age, PF or PPF, no depressive symptoms, laughter (almost every day or 1–5 times/week), talking almost every day, participation in community activities more than once a week, smoking habits (current or past), daily drinking habits, and physical activity (light and regular). After multivariate adjustment (Model 2), the factors that remained significantly associated with the prevalence of OF included age, women, no depressive symptoms, laughter (almost every day), smoking habits (current or past), and daily drinking habits. However, the associations with talking and participation in community activities, which were significant in Model 1, were no longer statistically significant in Model 2. Although there was an association between women and OF in Model 2, this association disappeared when smoking habit was excluded from the analysis, resulting in an OR (95%CI) of 1.16 (0.83–1.63) for women (data not shown) due to confounding by smoking.

Table 3 shows the ORs and 95% CIs for each factor considered in the multivariate models (Model 2) using logistic regression analysis for the prevalence of OF by sex and age category, with the reference group being those without OF (ORO + OPF).

In both men and women, significant associations were observed between the prevalence of OF and age, depressive symptoms, and current smoking habits, along with a significant trend for laughter almost every day. Additionally, in men, there was a significant association with daily drinking as well as significant trends for laughter 1–5 times/week and past smoking habits. In women, there was a significant association with DM, along with a significant trend for occasional drinking.

In the age category of 60–69 years, significant associations were found between the prevalence of OF and age, depressive symptoms, and current smoking habits. There were also significant associations with past smoking habits, daily drinking habits, physical activity (both light and regular), and laughter (almost every day, 1–5 times/week), along with a significant trend for occasional drinking. In the age category of 70–79 years, significant trends were also observed for PF and talking 1–5 times/week. No significant differences were found in either age category for participation in community activities.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of residents in Fukushima Prefecture, negative associations with the prevalence of OF were found for the frequencies of laughter and social communication—such as talking and participation in community activities—no depressive symptoms, and physical activity. Conversely, positive associations with the prevalence of OF were found for PF and lifestyle factors (such as smoking and drinking habits). The associations between laughter (almost every day or 1–5 times/week), no depressive symptoms, current smoking habits, and PF or PPF and the prevalence of OF were particularly pronounced, even after stratifying by sex and age category. Poor oral function is associated with physical deterioration, such as PF and sarcopenia14, and improving or preventing OF is likely to help prevent PF. Thus, interventions that incorporate laughter and approaches to reduce depressive symptoms may be effective in improving OF.

The prevalence of OF among our participants was 41.5%, with a higher prevalence observed in those in their 70s, consistent with reports of declining oral function with age38. Previous reviews have noted an increase in frailty with age, with a higher prevalence among women39,40. However, among all participants in this study, 2.7% had PF, 53.8% had PPF, with little difference in prevalence rates between men and women, and 48.6% were robust in their 70s. This variation may be attributed to the relatively young age range (60–79 years) of the study participants compared with those in other studies. Additionally, the use of maximum walking speed, as opposed to normal walking speed, may have resulted in a more lenient determination of PF than in other studies. Further studies should compare results obtained from assessing both normal and maximum walking speeds.

Several meta-analyses have highlighted the positive effects of laughter on both physical and mental health22,23,24. Laughter has been shown to improve vascular endothelial function41 and activate the brain42. Muscular engagement during laughter, which involves thoracic, abdominal, and facial muscles, may enhance cognitive function by increasing blood flow through cerebral blood vessels. Individuals who report less frequent laughter are associated with a higher risk of cognitive decline, elevated rates of total mortality, and an increased need for caregiving43. Additionally, laughter contributes to increased daily energy expenditure44 and engages facial muscles, potentially improving and preventing OF. Moreover, depression reduces laughter45, whereas laughter alleviates depression through stress reduction22, which may improve both OF and psychological frailty. Those who laugh every day report lower rates of lifestyle-related diseases46, indicating a potential preventive role for laughter in OF. In Japan, health classes for older participants often include OF countermeasures, such as face and tongue exercises. Consistent participation in these classes is crucial for maintaining physical and mental function, and laughter classes particularly demonstrate high participation and continuity rates47. A laughter intervention program combining laughter yoga (simulated laughter) and rakugo (spontaneous laughter), conducted across multiple facilities, observed improvements in participants’ physical and mental well-being due to the exercise and stress-relieving effects of laughter, along with a high participation rate25. Social activities and interactions with family and friends contribute to increased laughter in daily life48. A previous laughter intervention study noted a significant increase in the social network (frequency of meeting people) among participants in the intervention group25. In the present study, the frequency of laughter was correlated with the frequencies of talking (r = 0.31, p < 0.0001) and participation in community activities (r = 0.13, p = 0.0001), aligning with the association of laughter frequency with social factors. Meanwhile, it has been reported that shorter conversation times are associated with worse swallowing function49. Decreased social activity, leading to reduced conversation and lower tongue pressure, has been directly linked to OF50. In this study, those who talked almost daily or participated in community activities more than once a week had lower ORs for having OF. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies involving conversation and social networks49,51. Further studies should evaluate causality longitudinally, including psychological factors such as the SF-36 questionnaire52,53, to assess the broader impact of OF on health-related quality of life.

Depressive symptoms were strongly associated with the prevalence of OF in both men and women, consistent with findings reported by Tanaka et al., who indicated that those with OF had higher depression scores14. Individuals with depression may experience oral dryness due to antidepressant medication and their depressed mood, leading to poor oral hygiene, increased dental caries, and worsening periodontal disease54. Additionally, depression likely prevents people from receiving appropriate dental care. A depressed mood may result in decreased tooth brushing frequency, which could be strongly associated with OF. Although comparisons cannot be made because actual oral conditions, such as caries and periodontitis, were not investigated, the results were stratified by age category, revealing that more factors associated with OF were found in participants in their 60s than in those in their 70s. This is likely because middle-aged and older adults have more remaining teeth and periodontal disease, and they may be more susceptible to social factors, such as work and family, which can be related to depression55. Because depression is linked to a worsening oral environment54 and is a cause of frailty onset56,57, it is important to implement measures to address depressive symptoms.

The strengths of this study are twofold. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first epidemiological study on the association between OF prevalence and laughter. Second, the study achieved an overall high participation rate (93.1%), indicative of a strong inclination for engagement within this population. Given that laughter does not require specialized skills and can be easily embraced by individuals anywhere and at any time, it presents a cost-effective measure if incorporated as a preventive strategy for OF. In an intervention study conducted by the authors, participants with metabolic risk factors experienced physical and mental benefits, including improved health-related quality of life and well-being, reduced stress and depression, and weight loss25. Laughter classes also demonstrate a high retention rate among participants, suggesting that social activities are likely to persist and contribute to an increase in healthy life expectancy through improved OF. Laughter yoga is now widespread in more than 100 countries, and with many laughter yoga clubs throughout Japan, it can be easily incorporated into public health strategies at the local government level.

This study has several limitations. First, although the participation rate in the medical examinations was high, the age range of participants was relatively young (60–79 years old), and older adults aged > 80 years were excluded, which may lead to biased results compared with the general population. However, participation in these examinations was voluntary, and healthier, more active individuals aged > 70 years tended to be more willing to participate. Therefore, the prevalence of OF may be low even if the participants included those older than 80 years. In fact, half of the 14 participants over the age of 80 years who were excluded from the analysis had OF. However, the small sample size made evaluation difficult. Given that people in their 50s and 60s are in an age group where awareness of oral function decline exists but awareness of physical function decline is low58, it would be beneficial to survey younger participants, particularly those in their 60s and 70s, to screen for OF as early as possible. Second, because no oral examination was conducted and the evaluation was subjective, the results may differ from actual oral conditions, such as the presence or absence of dental treatment, number of teeth, and presence or absence of dentures. However, according to Tanaka et al.17, the area under the curve was 0.88 for those with an OFI-8 score of ≥ 4, which is comparable to conventional measures of OF calculated by chewing ability, tongue pressure, number of natural teeth, articulation oral motor skills, and subjective items (e.g., difficulty in eating hard foods and swallowing). Therefore, similar results are likely to be expected from subjective evaluations. Furthermore, a 1-point increase in the OFI-8 score is associated with an increased risk of developing OF and physical disability17. Thus, the OFI-8 assessment is likely to be useful in large-scale health examinations as it enables screening for OF without an oral examination. Although dental checkups examine dental caries and periodontal disease, it seems necessary to introduce risk assessments for the development of OF, such as the OFI-8, in addition to regular dental checkups to detect OF at an early stage, particularly in older adults. Third, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–2021 may have imposed greater restrictions on outings and activities than usual, rendering individuals more susceptible to frailty and OF. Indeed, a cohort of community-dwelling individuals aged ≥ 70 years reported worsening mental health, declining physical health, and reduced quality of life due to the pandemic59,60. Therefore, the prevalence of OF and frailty observed in this survey during the COVID-19 pandemic may exceed typical levels, necessitating future longitudinal investigations. Fourth, although we assessed the association of OF with depressive symptoms using a questionnaire, we did not investigate depression or antidepressant medication in participants’ medical histories and were unable to adjust for these factors. However, the PRIME-MD33 was developed to screen for psychiatric disorders, and its validity and effectiveness have been evaluated, making it suitable for screening psychiatric symptoms in a straightforward manner during health examinations like the present study. Finally, because this was a cross-sectional study, it is difficult to determine causal relationships. However, it is unlikely that laughter and social communication decrease due to OF. Further longitudinal research is needed to confirm whether laughter and social communication can prevent the onset of OF.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional study revealed that the frequencies of laughter and social communication, and depressive symptoms is associated with OF. Because OF is linked to the development of frailty, which may further lead to cerebrovascular disease, it is necessary to increase the frequencies of laughter and social communication while reducing depressive symptoms associated with OF to enhance healthy life expectancy. Additionally, laughter, which is effective in improving both physical and mental health, may serve as a preventive measure against frailty caused by multiple factors. It could be implemented as a public health strategy to prevent disease and reduce a need for care among residents.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, as they belong to Naraha Town. However, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Statistics Bureau Home Page/Population Estimates Monthly Report. Statistics Bureau of Japan (2024). https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/jinsui/tsuki/index.html

Population Projections for Japan: 2021 to 2070. National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (2023). https://www.ipss.go.jp/pp-zenkoku/e/zenkoku_e2023/pp_zenkoku2023e.asp.

Ofori-Asenso, R. et al. Global incidence of Frailty and Prefrailty among Community-Dwelling older adults: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 2, e198398 (2019).

Clegg, A., Young, J., Iliffe, S., Rikkert, M. O. & Rockwood, K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 381, 752–762 (2013).

Zhao, W. et al. Effect of physical activity on the risk of frailty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 17, e0278226 (2022).

Makizako, H. et al. Physical Frailty and Future Costs of Long-Term Care in Older Adults: Results from the NCGG-SGS. Gerontology. 67, 695–704 (2021).

Shimazaki, Y. et al. Oral hypofunction and its association with frailty in community-dwelling older people. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 20, 917–926 (2020).

Nakamura, M. et al. Association of Oral Hypofunction with Frailty, Sarcopenia, and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Cross-Sectional Study of Community-Dwelling Japanese Older Adults. J. Clin. Med. 10, 1626 (2021).

Ansai, T. et al. Relationship between tooth loss and mortality in 80-year-old Japanese community-dwelling subjects. BMC Public. Health. 10, 386 (2010).

Wang, M. et al. Frailty mediated the association between tooth loss and mortality in the oldest old individuals: a cohort study. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1285226 (2023).

Dibello, V. et al. Oral frailty and its determinants in older age: a systematic review. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2, e507–e520 (2021).

Oral Frailty Manual 2019 Edition. Japan Dental Association (2019). https://www.jda.or.jp/en/pdf/Oral_Frailty_Manual-Whole_Version.pdf?20230620.

Robison, R. et al. New horizons in understanding oral health and swallowing function within the context of frailty. Age Ageing. 52, afac276 (2023).

Tanaka, T. et al. Oral Frailty as a Risk Factor for Physical Frailty and Mortality in Community-Dwelling Elderly. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 73, 1661–1667 (2018).

Parisius, K. G. H. et al. Oral frailty dissected and conceptualized: A scoping review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 100, 104653 (2022).

Minakuchi, S. et al. Oral hypofunction in the older population: Position paper of the Japanese Society of Gerodontology in 2016. Gerodontology. 35, 317–324 (2018).

Tanaka, T., Hirano, H., Ohara, Y., Nishimoto, M. & Iijima, K. Oral Frailty Index-8 in the risk assessment of new-onset oral frailty and functional disability among community-dwelling older adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 94, 104340 (2021).

Noguchi, T. et al. Association between community-level social capital and frailty onset among older adults: a multilevel longitudinal study from the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES). J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 76, 182–189 (2022).

Abe, N. et al. Social participation and incident disability and mortality among frail older adults: A JAGES longitudinal study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 71, 1881–1890 (2023).

Lau, L. K. et al. Effects of Exercise Interventions on Physical Performance and Activities of Daily Living in Oldest-Old and Frail Older Adults: A Review of the Literature. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 102, 939–949 (2023).

Ni Lochlainn, M. et al. Nutrition and Frailty: Opportunities for Prevention and Treatment. Nutrients. 13, 2349 (2021).

van der Wal, C. N. & Kok, R. N. Laughter-inducing therapies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 232, 473–488 (2019).

Demir Doğan, M. The Effect of Laughter Therapy on Anxiety: A Meta-analysis. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 34, 35–39 (2020).

Zhao, J. et al. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of laughter and humour interventions on depression, anxiety and sleep quality in adults. J. Adv. Nurs. 75, 2435–2448 (2019).

Funakubo, N. et al. Effects of a laughter program on body weight and mental health among Japanese people with metabolic syndrome risk factors: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 22, 361 (2022).

Shirai, K. et al. Perceived level of life enjoyment and risks of cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality: the Japan public health center-based study. Circulation. 120, 956–963 (2009).

Hayashi, K. et al. Laughter is the Best Medicine? A Cross-Sectional Study of Cardiovascular Disease Among Older Japanese Adults. J. Epidemiol. 26, 546–552 (2016).

Yamaguchi, S. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Check-ups: A Nationwide Questionnaire Survey in 639 Healthcare Facilities in Japan Society of Ningen Dock. JMA J. 6, 321–331 (2023).

Fried, L. P. et al. Frailty in Older Adults: Evidence for a Phenotype. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56, M146–M157 (2001).

Satake, S. et al. Prevalence of frailty among community-dwellers and outpatients in Japan as defined by the Japanese version of the Cardiovascular Health Study criteria. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 17, 2629–2634 (2017).

Yamada, M. Outcome Measurement in Care Prevention. Phys. Ther. Jpn. 47, 499–504 (2020).

Hirosaki, M. et al. Association between frequency of laughter and oral health among community-dwelling older adults: a population-based cross-sectional study in Japan. Qual. Life Res. 30, 1561–1569 (2021).

Spitzer, R. L. et al. Utility of a New Procedure for Diagnosing Mental Disorders in Primary Care: The PRIME-MD 1000 Study. JAMA. 272, 1749–1756 (1994).

Whooley, M. A., Avins, A. L., Miranda, J. & Browner, W. S. Case-Finding Instruments for Depression. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 12, 439–445 (1997).

Li, Y. et al. A Pilot Study of the FRAIL Scale on Predicting Outcomes in Chinese Elderly People With Type 2 Diabetes. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 16, 714e7–714e12 (2015).

Liccini, A. & Malmstrom, T. K. Frailty and Sarcopenia as Predictors of Adverse Health Outcomes in Persons With Diabetes Mellitus. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 17, 846–851 (2016).

Williamson, J. D. et al. Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control and Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes in Adults Aged ≥ 75 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 315, 2673–2682 (2016).

Watanabe, Y. et al. Relationship Between Frailty and Oral Function in Community-Dwelling Elderly Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 65, 66–76 (2017).

Collard, R. M., Boter, H., Schoevers, R. A. & Oude Voshaar, R. C. Prevalence of Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older Persons: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 60, 1487–1492 (2012).

Oishi, Y. & Kishimoto, H. Sex difference on the prevalence of physical frailty in a community-dwelling older people. J. Health Sci. 44, 33–39 (2022).

Sugawara, J., Tarumi, T. & Tanaka, H. Effect of mirthful laughter on vascular function. Am. J. Cardiol. 106, 856–859 (2010).

Takayanagi, K. The Laughter Therapy. Jpn J. Complement. Altern. Med. 4, 51–57 (2007).

Tamada, Y. et al. Does Laughter Predict Onset of Functional Disability and Mortality Among Older Japanese Adults? The JAGES Prospective Cohort Study. J. Epidemiol. 31, 301–307 (2021).

Buchowski, M. S. et al. Energy expenditure of genuine laughter. Int. J. Obes. 31, 131–137 (2007).

Fonzi, L., Matteucci, G. & Bersani, G. [Laughter and depression: hypothesis of pathogenic and therapeutic correlation]. Riv Psichiatr. 45, 1–6 (2010).

Eguchi, E. et al. Association between Laughter and Lifestyle Diseases after the Great East Japan Earthquake: The Fukushima Health Management Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 12699 (2021).

Hirosaki, M. et al. Lifestyle factors and social ties associated with the frequency of laughter after the Great East Japan Earthquake: Fukushima Health Management Survey. Qual. Life Res. 27, 639–650 (2018).

Imai, Y. et al. Impact of social relationships on income–laughter relationships among older people: the JAGES cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 8, e019104 (2018).

Hagiwara, A. et al. Factors Associated With Swallowing Function Among Physicians in Their 50s and 60s: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus. 15, e47921 (2023).

Hironaka, S. et al. Association between oral, social, and physical frailty in community-dwelling older adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 89, 104105 (2020).

Iijima, K. Upstream preventive strategy for age-related sarcopenia in the elderly: Why do the elderly fall into inadequate nutrition? Ann. Jpn Prosthodont. Soc. 7, 92–101 (2015).

Ware, J. E. & Sherbourne, C. D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care. 30, 473–483 (1992).

Fukuhara, S., Ware, J. E., Kosinski, M., Wada, S. & Gandek, B. Psychometric and Clinical Tests of Validity of the Japanese SF-36 Health Survey. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 51, 1045–1053 (1998).

Almohaimeed, B., Dube, S. R. & Luo, R. Investigating oral health among individuals with depression: NHANES 2015–2016. Saudi Dent. J. 34, 249–258 (2022).

Funakubo, N. et al. Association between Psychosocial Factors and Oral Symptoms among Residents in Fukushima after the Great East Japan Earthquake: A Cross-Sectional Study from the Fukushima Health Management Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 6054 (2021).

Vaughan, L., Corbin, A. L. & Goveas, J. S. Depression and frailty in later life: a systematic review. Clin. Interv Aging. 10, 1947–1958 (2015).

Ramsay, S. E. et al. Influence of Poor Oral Health on Physical Frailty: A Population-Based Cohort Study of Older British Men. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 66, 473–479 (2018).

Hihara, T., Goto, T., Yanagisawa, S., Nakamichi, A. & Ichikawa, T. The Symptoms of Oral Frailty and Physical Frailty in Every Age Group. Ronen Shika Igaku. 32, 33–47 (2017).

Bailey, L. et al. Physical and mental health of older people while cocooning during the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM Int. J. Med. 114, 648–653 (2021).

Shinohara, T., Saida, K., Tanaka, S. & Murayama, A. Association between frailty and changes in lifestyle and physical or psychological conditions among older adults affected by the coronavirus disease 2019 countermeasures in Japan. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 21, 39–42 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff of Naraha Town. We would like to express our gratitude to the staff of the Department of Epidemiology at Fukushima Medical University for their continued cooperation. Additionally, we sincerely thank the students of Fukushima Medical University.

Funding

The study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (grant numbers 19K19767, 19K10626, 20K19712, 20K10507, 21KK0168, 22H03352, 23K16231 and 23H03167) and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development under Grant Agreement (grant number JP22rea522104).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: NF, KO, EE, YF, TO; methodology: NF, KO, FH, TO; formal analysis: NF, FH; supervision: TO; project administration: TO; data curation: NF; investigation: NF, KO, FH, EE, MN, HN, MN, TY, MY, NM, YF, TO; funding acquisition: NF, KO, FH, EE, TO; validation: FH; writing—original draft: NF; Writing—review and editing: KO, FH, EE, MN, HN, MN, TY, MY, NM, YF, TO. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Funakubo, N., Okazaki, K., Hayashi, F. et al. Association of laughter and social communication with oral frailty among residents in Fukushima: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 14, 26818 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77966-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77966-7