Abstract

Australia’s 2019/20 bushfire season was one of the most severe on record, from both land mass burned and the economic impact. This extreme weather season allowed the researchers to examine the effect of high PM2.5 exposure during high bushfire days on birthweight and gestational age. It is well known that bushfire smoke is harmful to human health. However, the impact this has on the developing fetus is not yet clear. 25,346 births were assessed, their exposure calculated based on location data, and outcomes analyzed. Mothers exposed to high PM2.5 (measured by a 24-hour average PM2.5 greater than 25 µg/m3) demonstrated a significant birthweight reduction of 0.77 g per day of exposure. Those who were also self-identified as having smoked at any time during their pregnancy were at higher risk, with a 1.33 g reduction in birthweight per day of exposure. Gestational age was reduced by 0.01 days per day of exposure in the total cohort, with no significant difference demonstrated in those who smoked. The compounded effects of high PM2.5 exposure may result in birthweight reduction, with neonates born to mothers who smoked at increased risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) and Global Burden of Diseases study report that ambient air pollution levels were above recommended levels for 99% of the world population, resulting in 4.2 million premature deaths yearly in 20151,2. Particulate matter (PM) is the most hazardous component of air pollution1,3,4, and PM2.5(particles with a diameter of 2.5 μm or less) are of the greatest concern to health due the very small size5. The cardiovascular and respiratory system are damaged from inhalation and transport of PM2.5through the systemic bloodstream leading to increased morbidity and mortality1,4.

There is currently less evidence for the effects of air pollution on human foeti. However it is considered that human foeti are highly vulnerable to air pollution from anthropogenic and natural sources6. Current research has highlighted an association between chronic PM2.5exposure and low birthweight and gestational age2. In acute PM2.5increases such as those seen in bushfires, the evidence is limited but has highlighted potentially similar patterns6,7.

The WHO reports that while most mortality attributable to air pollution occurs in the developing world, many countries are at risk, especially during disasters such as bushfires3. Furthermore, human activity causing climate change has been linked to increasing global large-scale environmental bushfire events8. Oldenborgh et al. attributed an increase of at least 30% in the Fire Weather Index (index used to estimate fire danger), within Australia due to anthropogenic global warming9. Combined with the worsening nature of climate change, this represents a severe risk of further bushfire events.

The 2019/20 bushfire season in Australia, known as Black Summer, was of high-severity, caused by unusually dry weather conditions, erratic fire behavior, and a combination of human activity and lightning10. Over 17 million hectares were burnt across mainland Australia, recording the most extensive total area burnt in New South Wales (NSW) history10. This resulted in extremely poor air quality, with exposure to PM2.5concentrations exceeding the 95th percentile of historical mean data11. The NSW background daily mean PM2.5 level is 8 µg/m312. Therefore, it is concerning that in 2019, PM2.5levels were over this standard in one or more population center(s) on 118 days, compared to 52 days in 201812. Total days over the Australian criteria of poor air quality for PM2.5 24 h average threshold of 25 µg/m3in NSW for 2019 peaked at 60 in Armidale13,14.

The bushfire events of 2019/2020 raised further concern about the health impact of smoke particulates on pregnant people and their fetuses. However, the majority of health advice at the time focused on pregnant people with existing respiratory conditions, and not the health risks for the general pregnant population and their foetus15. This lack of clarity demonstrated inadequate existing research to inform individuals, health practitioners, and policy makers as to the requirement for health risk mitigation for the human fetus in acute peaks of PM2.5 levels.

Further, a 2021 systematic review by Amjad et al6. found few relevant studies on the health risks of bushfire smoke, with significant heterogeneity in methodology and resultsand a reduction in birthweight and gestational age5. This publication was unable to demonstrate a specific effect measure, however, did highlight in the 7 studies looking at birthweight, 6 showed reduction, and for pre-term birth, there were equal studies in each direction. Significant limitations noted in this paper included limited confounding factors, ambient air pollution level assessment, and variance in exposure assessment. This paper aims to address some of these issues and create a standard for research in this area.

A lack of consensus of evidence on the health implications of biomass burning smoke and the recent bushfire events in Australia necessitates further investigation16. The relationship between high PM2.5 from bushfire smoke during pregnancy and the effect upon neonatal outcomes of birthweight and gestational age is essential for protecting human health.

Tobacco smoking is a significant risk factor for mother and baby in pregnancy, causing a multitude of adverse outcomes17. Tobacco smoking poses similar risks to exposure to PM2.5, such as low birthweight and increased chances of preterm birth6. Hence, exploring the subgroup of pregnant people who smoked during pregnancy compared to those who did not is valuable for further investigation. Considering the possibility of a synergistic effect between tobacco smoke and bushfire smoke exposure, Kumar et al., in 2021 emphasized the importance of studying pregnant people exposed to both bushfire smoke and tobacco smoke as a high-priority research area18.

This study aims to investigate the effects of high PM2.5 during high bushfire smoke days through the significant 2019/20 Australian bushfire season on the outcomes of birthweight and gestational in the Hunter New England Local Health District (HNELHD) of NSW, Australia. As tobacco smoking presents some of the same risks as exposure to PM2.5including low birthweight and higher rates of preterm birth17,19, a secondary analysis of those who smoked tobacco at any time during pregnancy and those who did not was included. This subgroup’s exposure was measured utilizing the same methodology as the primary group.

The primary hypothesis is that a relationship exists between people exposed to high PM2.5 and a decrease in birthweight and gestational age. The secondary hypothesis is that people who report smoking tobacco during their pregnancy are at an increased risk for these adverse neonatal outcomes.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study focuses on the suburbs within the Armidale, Beresfield, Gunnedah, Muswellbrook, Narrabri, Singleton, and Tamworth regions of NSW that were impacted during the 2019/20 bushfire season20. These locations are all based within the local health district (LHD) of Hunter New England (HNE). This LHD covers a land area of 132,845 square kilometers and 840,000 people21. In 2021, HNE recorded 11,221 births, 11.4% of the total number for the state of NSW22. Economically, the health area covers the national census areas of Hunter, with a median household income of $1,593 per week, and New England and North West, with a median weekly household income of $1,328. These are compared to the Australian national average median weekly household income of $1,74623,24. This local health district was selected as it was the single most affected LHD by the number of days over the determined threshold (≥ 25 μm/m3)14. As each LHD collects, stores and, releases data separately, assessing the state as a whole was not feasible.

Date of birth data was collected from 01/04/2016 through to 31/08/2020. This date range was selected to encompass times of no bushfire activity and the significant events of 2019/20 to ensure large cohorts of both exposed and non-exposed. This resulted in an initial data set of 126,644 births. However, some records were excluded due to the availability of air quality data in that location at the time of birth. The data monitoring stations that collect PM2.5 data were not all constructed at the outset of the data collection period. Further records were excluded for duplicate entries and suburb locations compared to air quality monitoring locations. This resulted in an initial cohort of 27,103 records.

Based on population density data, the sampled population was created using a 30 km radius around the Regional and Rural Air Quality Monitoring Network centers. This distance allowed the capture of all residents who reside in the local government areas with the monitoring station, per the definition of > 25,000 population25. People residing within these suburbs were selected and allocated to their closest monitoring center (Fig. 1)26.

Areas of Northern NSW affected by bushfire activity in 2019/20 (illustrated by brown shading) , with an overlaid 30 km radius for the selected monitoring centers (red) within HNELHD (blue). Adapted from NSW Government26.

Regional PM2.5 24-hour average data was obtained from the Department of Planning and Environment Air Quality Concentration Data (Appendix 1). The centers use either 5014i Beta Continuous Ambient Particulate Monitor or Thermo SHARP 5030 Beta Attenuation Method monitors, conformed to Australian and International Standards to record hourly PM2.5 levels expressed as mass of particulate matter (micrograms) per cubic meter of air (µg/m3)27. This study used daily average PM2.5recordings from these centers to quantify the cohort’s level of exposure as a surrogate for bushfire smoke. This method of quantifying exposure is consistent with previous research in this area6,28,29. The data undergoes on-the-field regular diagnostic tests, calibration checks, and post-data-collection procedures to ensure the quality and reliability of the trends in exposure over time27. In total 7, monitoring sites were utilized: Beresfield, Singleton, Muswellbrook, Tamworth, Gunnedah, Armidale, and Narrabri. If the mother’s address postcode did not fall within the 30 km radius of these sites, their data was excluded.

The ObstetriX and eMaternity databases are the Maternal Information System of HNELHD that reports to the Ministry of Health30. Following ethics and data access approval from the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC Reference no. 2020/ETH03210) and the Maternal and Gynecology Research Governance Committee, the study obtained de-identified records (Appendix 2) for the requested suburbs and their corresponding PM2.5 data periods (Appendix 1). The methodology was undertaken adhering to the guidelines set out by the HREC.

PM2.5 recordings expressed as micrograms of particulate matter per cubic meter of air (µg/m3) 24-hour average were used to quantify the level of exposure of the cohort as a surrogate for bushfire smoke14.

The following maternal and fetal variables were available from the Maternal Information System:

-

1.

Fetal factors: date of birth, gestational age (Weeks and days of completed gestation), birthweight (Grams), gender (M/F), birth outcome (Live birth / Stillbirth), type of delivery (Vaginal/Caesarean section/ Instrumental) and fetal growth restriction (Confirmed on Ultrasound < 10th Percentile standardized for sex and age/Clinically suspected/No).

-

2.

Maternal factors: age, previous pregnancies, smoking during pregnancy (Yes/No), diabetes (Yes/No/Unknown), hypertension (Yes/No/Unknown), anemia (Yes/No/Unknown), maternal body mass index (BMI) and ethnicity (Indigenous/Non-Indigenous).

The factors selected represent those available within the maternity data set from those which are known to have an impact on fetal outcomes31.

For analysis, the following binary variables required combining and calculating multiple entries within the data set due to numerous areas for adding these datapoints to the database. These included fetal growth restriction, previous pregnancies, smoking at any time during pregnancy, diabetes, anemia, and hypertension. BMI was calculated based on booking weight (Weight at the first visit to the anti-natal clinic) and height.

Gestational age at birth was based on the best clinical estimate using either the last menstrual period or dating ultrasound scans. Birthweight is measured in grams and aimed to be taken within the first hour of life.

Categorical variables were combined within the data set, as shown in Appendix 2 (E.g., All fetal anomalies recorded were allocated yes in Yes/No categorization). Duplicate entries related to suburbs outside the 30 km radius and births outside the PM2.5 data collection period were removed. Exclusion criteria: multiple births, fetal anomalies, gestational age less than 24 weeks, and < 400 g birth weights were applied, as seen in Fig. 2. These additional exclusion criteria were added due to the viability of the births. These criteria are also seen in Holstius et al. 2012 and Abdo et al. 201929,32.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysiswas performed using STATA 16 software33. We used descriptive statistics to summarize the characteristics of the neonates and mothers. The exposure of pregnant people to PM2.5 was quantified using the Australian Government Poor Air Quality threshold of greater than 25 µg/m3when given as an average over 24 h13. Therefore, if the average level recorded for a date was above this threshold, the pregnant people residing within that area were considered exposed for one day. This led to a continuous exposure variable calculated from the discrete number of days exposed. Self-reported maternal tobacco smoking at any time during the pregnancy produced a secondary analysis. These groups were then assessed using linear regression analysis to understand the relationship between the exposure and outcomes when controlling for confounders. This assessment was undertaken as a separate analysis, with smoking the only additional factor. This analysis followed the same steps as that for the complete cohort.

An assessment for multicollinearity was undertaken using variance inflation factor (VIF) with a standardized cut-off of 10 considered significant. All variables within the models returned a VIF < 10.

The data was analyzed using linear regression modeling and multivariate analysis. A univariate analysis assessing only the exposure variable and outcome variable was initially undertaken before multivariate analysis to complete this. The multivariate analysis incorporated the potential confounders (As seen in Table 1) and assessed their impact in combination toward the outcome measure. This allowed the assessment of the effects of the exposure variable when taken in the context of the other confounders. Therefore, the significance of a single confounder can be assessed more clearly.

Regression analysis was completed with an initial univariate analysis, and a full fitting model and reductionist methodology were applied to all models. Reported P values and adjusted R-squared values were used to create the parsimonious models. At all stages, a P value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Variables that had no significant impact were removed from the final model. Residual diagnostics, including residual versus fitted plots, were used to assess model validity. Regression results were presented as beta coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P values for each variable.

Results

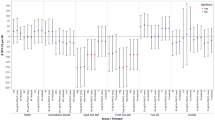

Table 1 illustrates a descriptive analysis of the complete cohort variables. A significant difference in exposed and non-exposed populations was seen in the categorical variables: PM2.5 tower location (The suburb in which the air quality monitoring site resided) (P < 0.001), previous pregnancies (P = 0.03), ethnicity (P = < 0.001), birth type (P < 0.01) and anemia (P < 0.001). Mean t-testing was performed on continuous variables; only gestational age was significant (P = 0.04). Those identified as exposed to high levels of PM2.5 experienced similar rates of all variables to those identified as not exposed to high levels of PM2.5. The exposure variable ranged from 0 to 64 days, with a mean of 6.18 days in the total cohort and 15.3 in the exposed cohort.

Table 2 illustrates descriptive analysis for the secondary cohort variables divided into people who smoked (N = 4326) and those who did not smoke (N = 21020). The chi-squared analysis demonstrated a significant difference for all categorical variables except gender (P = 0.33) and anemia (P = 0.78). T-test analysis demonstrated significant results for all continuous variables other than the expected days of PM2.5 exposure (P = 0.64).

Table 3 shows the birthweight analysis for the complete cohort. Univariate analysis demonstrated a 0.44 g decrease in birthweight for each day of exposure to PM2.5 over 25 µg/m3 (P = 0.13, 95% CI [1.0, 0.13]). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that for each day of exposure to PM2.5 over 25 µg/m3, there was a 0.77 g statistically significant reduction in birthweight (P < 0.001, 95% CI [1.19, 0.36]).

In the cohort of mothers who smoked tobacco during their pregnancy, the reduction in birthweight was greater than those who did not smoke (Table 4). The univariate analysis demonstrated a non-significant trend for a reduction of 0.96 g per day of exposure (P = 0.12, 95% CI [2.42, 0.50]). However, multivariate analysis showed a statistically significant reduction of 1.33 g for each day of exposure (P = 0.01, 95% CI [2.33 to 0.33]).

Gestation (Days) was assessed in both the complete cohort and people who smoked tobacco versus those who did not. Univariate analysis of the complete cohort demonstrated a non-significant increase in gestation of 0.01 days for each day of exposure (P = 0.18, 95% CI [0.00, 0.02]) (Table 5). The multivariate modeling shows a statistically significant increase of 0.01 days gestation for each day of exposure (P < 0.01, CI [0.00, 0.02]). This model was adjusted for birthweight, gender, smoking status, fetal growth restriction, previous pregnancy, birth type and maternal BMI.

The univariate analysis for people who smoked tobacco during pregnancy (Table 6) demonstrated a non-significant gestation increase of 0.01 days for each day of exposure (P = 0.71, CI [-0.03, 0.04]) and non-significant multivariate analysis (P = 0.31, CI [-0.01, 0.04]). This model was adjusted for birthweight, gender, diabetes, previous pregnancy, and maternal BMI. The fetal growth restriction and birth type variables were excluded compared to the complete cohort.

Gender specific analysis was undertaken utilizing the parsimonious models from the complete cohorts. The output for both birthweight and gestational age was considered non-significant (P = 0.86, and P = 0.92, respectively).

Discussion

In a cohort of 25,346 people who were exposed to PM2.5 levels above and below the Australian Government safe level cut off (25 µg/m3 daily average) in the region of Hunter New England, NSW, Australia, the study demonstrated a small but statistically significant reduction in birthweight of 0.77 g (P < 0.001) per day of exposure. Further, this was shown to have a greater effect in the cohort of mothers who smoked tobacco at any time compared to others who did not smoke tobacco at any time, with a 1.33 g reduction (P = 0.01). The additional gender analysis demonstrated no difference in birthweight (P= 0.86). Low birthweight is an indicator of growth retardation, signifying an increased susceptibility to complications arising from the underdevelopment of the pulmonary, nervous, digestive, and immune systems17. Despite the clinical insignificance of the observed effect, the combined influence of tobacco and PM2.5, acting synergistically to impact birthweight, underscores the need for heightened efforts in promoting smoking cessation among pregnant people, especially those living in areas with high PM2.5 exposure risk, such as bushfire susceptible areas.

The secondary outcome of gestational age found a statistically significant increase of 0.01 days (P < 0.01) for each day of exposure in the complete cohort. However, the cohort of mothers who smoked tobacco showed no significant change in gestational age.

The negative association between birthweight and exposure to PM2.5demonstrated in this study aligns with seven of the eight relevant previous studies6,16,28,29. The O’Donnell and Behie study which, demonstrated a positive association, only demonstrated this in the male cohort34. This was not seen in our gender analysis. It must be noted, however, that it is difficult to compare the weight reduction in the present study with that of previous studies due to the heterogeneity of methodologies and result reporting.

The additional assessment of maternal tobacco smoking was not seen in previous studies. However, it is plausible to assume that for people who are exposed to tobacco smoke, the compounded effect of PM2.5leads to a greater reduction in birthweight17,18. Other factors such, as additional time spent outdoors to smoke, more frequent smoking due to maternal stress, and exposure to second-hand smoke, may also account for the greater effect for people who smoke17,18.

While the birthweight reduction was small (0.77 g per day of exposure), including modeling for known confounders, the parsimonious model only demonstrated an R2adjusted result of 0.52. This result highlights the complexity of measuring birthweight and the potentially significant effect of other risk factors, such as maternal education, nutrition, and socioeconomic status, which were not assessed in this cohort35,36.

The analysis of gestational age found a significant increase of 0.01 days (p = 0.003) for each day of exposure to PM2.5 over 25 µg/m3 for the complete cohort. While this result is statistically significant, the increase in gestation equates to 14.4 min per day exposed, increasing the gestation by approximately 15 h for the most exposed mothers, which may not have clinical relevance. Further, it must be noted that the complete model (Before reduction) showed non-statistical significance. Therefore, the authors suggest this outcome be interpreted with caution.

Although tobacco smoking is a known risk factor for reduction in gestational age17, no statistically significant change was found in the group that smoked.

Other studies in the reviewed literature have found various associations between PM2.5exposure and gestational age; however, it is difficult to compare the studies due to the differing methods and format of results. Abdo et al29. found a 13.2% increase in the chance of preterm birth (classified as 37 weeks or less) for each increase of 1 µg/m3 of PM2.5in the second trimester, and O’Donnell & Behie34 found a small but significant increase in the incidence of preterm birth (P= 0.04). Two other studies found no statistically significant effect6.

The authors note that between the collection of data and publication, the WHO reduced their safe acute PM2.5 24-hour average cut off from 25 µg/m3 to 15 µg/m337. This change was in line with the interim target plan from their sustainable development goals, where target 1 was 35 µg/m3, target 2 was 25 µg/m3, target 3 was 15 µg/m3 and a final target of 10 µg/m3 37. This reduction is in response to a recent meta-analysis (Commissioned by WHO) by Orellano et al. (2020) demonstrating a linear relationship between short term PM2.5exposure (Hours to 1 week) and all-cause mortality38. However, as noted in the meta-analysis, there is no evidence of a safe level of PM2.5 exposure at this time. The varied standards for many countries echo this evolving understanding of PM2.5 exposure and its health effects. The European Commission outlines a standard of less than 20 µg/m3 averaged out over 1 year, which is down from 25 µg/m3in 201539. The United States Environmental Protection Agency outlines a 3-year average below 9 µg/m3 40. In contrast, the United Kingdom increased their target range in 2023 from less than 10 µg/m3 to less than 12 µg/m3averaged over a year41. None of these national guidelines are targets for single daily exposures as measured in this study. This lead the authors of this paper to utilize the current Australian national standard of less than 25 µg/m3 averaged over 24-hours, as it is known that some geographical differences in the relationship between PM2.5exposure and health exist13,38.

Strengths and limitations

One of the key strengths of this study is its large sample size, which includes data collected during a period of intense bushfires and high PM2.5. This study also outlined a new methodology for assessing exposure to PM2.5, which is feasible, reproducible, and sustainable. It is challenging to disentangle ambient PM2.5 from bushfire PM2.5when quantifying maternal exposure, a limitation noted in a systematic review6. Previous studies have used a combination of satellite imagery, wind direction, and PM2.5 levels to create a µg/m3exposure level6,28,29. The methodology within the present study used a count of days exceeding the PM2.5 24-hour average guideline level defined by the Australian Government. The ambient PM2.5for NSW is approximately 8 µg/m14; therefore, it can be rationally concluded that levels exceeding 25 µg/m3 can be attributed to PM2.5 producing events such as bushfires. It must be noted, however, that single or small clusters of days above this threshold do occur in this region without bushfires. This can be related to high dust days from dry conditions or coal dust from local mines. However, as previously highlighted, the 2019/20 days above the threshold were in unprecedented numbers correlating to days of bushfire activity.

The use of location radius to monitoring stations of 30 km from population density may not have accurately captured all exposed mothers. However, not limiting the radius may have incorrectly given exposure or non-exposure counts.

The data set available did not include all variables to impact gestational age and birthweight31. This limitation is noted in the review of current evidence by Amjad et al. (2021) as occurring in all current evidence6. At this time, data collection for a complete analysis would require a prospective study as many of the known factors that affect birth outcomes are not routinely collected in Australia.

The smoking cohort has additional limitations of unquantifiable smoking exposure. The data available for analysis did not quantify the amount smoked, duration of smoking, or time of cessation. These factors, along with known confounders associated with smoking, such as socioeconomic status, education levels, and partner smoking status, may affect the outcome42.

Finding a decrease in gestational age may be due to data limitations such as, inconsistencies in reporting gestational age, reliance on self-reported smoking data, and the use of categorical variables for reporting data.

Implications and recommendations

This research has several implications for future health research and practice. Firstly, it highlights the importance of addressing environmental factors, such as high PM2.5and air pollution from bushfires, in prenatal care to safeguard maternal and infant health. Additionally, these findings underscore the need for proactive public health measures during and after bushfire events, including targeted interventions to mitigate exposure risks for pregnant people. Moreover, healthcare providers may need to adapt their approaches to prenatal care and monitor infants closely for potential health implications associated with poor air quality exposure. These findings may also hold significant relevance for priority populations, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, individuals using substances, and those experiencing mental health concerns who exhibit higher rates of smoking during pregnancy17,18.

Since these findings are preliminary, additional research, both qualitative and quantitative, in the field of health services is necessary to understand current practices and determine the most effective approaches for managing PM2.5 exposure during prenatal care. A comprehensive examination of public health and policy measures is essential for making recommendations in both practice and policy.

Conclusion

This research analyzed 25,346 pregnant people and their newborns using the eMaternity database in NSW, Australia, alongside published air quality data from regions impacted by the 2019/20 bushfire season. This study underscores that exposure to high PM2.5 during pregnancy may lead to decreased birthweight, particularly pronounced in cases where mothers also smoked tobacco. Although a slight increase in gestational age was observed across the entire cohort, its clinical significance is limited.

Given the compounded impact of PM2.5 exposure alongside other factors contributing to reduced birthweight, coupled with the rising occurrence of Australian bushfires, it is imperative to address this issue. This study will help shape future health and disaster policies more effectively by providing crucial insights into the impact of PM2.5 exposure during pregnancy on newborns’ health.

Data availability

The data utilised in this paper is not freely available. Its access is restricted by Australian national law and would require application to the Hunter New England Local Health District of New South Wales Health.

References

World Health Organization. Ambient (outdoor) air pollution (2022). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health.

Cohen, A. B., Burnett, M., Anderson, R., Frostad, R. & Estep, J. Et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of diseases Study 2015. Lancet. 389, 1907–1918 (2017).

World Health Organization. Air quality guidelines for particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide (2006). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-SDE-PHE-OEH-06-02.

Stieb, D. M., Chen, L., Eshoul, M. & Judek, S. Ambient air pollution, birth weight and preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 100–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2012.05.007 (2012).

Makkonen, U. et al. Size distribution and chemical composition of airborne particles in south-eastern Finland during different seasons and wildfire episodes in 2006. Sci. Total Environ. 408, 644–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.050 (2010).

Amjad, S. Chojecki, D. Osornio-Vargas, A. & Ospina, M, B. Wildfire exposure during pregnancy and the risk of adverse birth outcomes: A systematic review. Enviroment International. 156, 106644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106644 (2021).

Bové, H. et al. Ambient black carbon particles reach the fetal side of human placenta. Nat. Commun. 10, 3866. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11654-3 (2019).

Basilio, E. et al. Wildfire smoke exposure during pregnancy: a review of potential mechanisms of placental toxicity, impact on obstetric outcomes, and strategies to reduce exposure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113727 (2022).

van Oldenborgh, G. J. et al. Attribution of the Australian bushfire risk to anthropogenic climate change. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 941–960. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-21-941-2021 (2021).

Richards, L., Brew, N. & Smith, L. 2019–20 Australian bushfires—frequently asked questions: a quick guide, (2020). https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1920/Quick_Guides/AustralianBushfires.

Borchers Arriagada, N. et al. Unprecedented smoke-related health burden associated with the 2019–20 bushfires in eastern Australia. Med. J. Aust. 213, 282–283. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50545 (2020).

NSW Department of Planning Industry and Enviroment. NSW Annual Air Quality Statement 2019, (2020). https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/air/nsw-air-quality-statements/annual-air-quality-statement-2019.

Australian Government Environmental Health Standing Committee. Health Guidance for 1-Hour PM2.5 and forecast 24-hour PM2.5 air quality categories and public health advice (2024). https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-07/pm2-5-air-quality-categories-and-public-health-advice_0.pdf.

NSW Goverment. Air Quality Concentration Data. (2024). https://www.airquality.nsw.gov.au/air-quality-in-my-area/concentration-data.

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Statement on prolonged exposure to bushfire smoke and poor air quality, (2020). https://ranzcog.edu.au/resources/statement-on-prolonged-exposure-to-bushfire-smoke-and-poor-air-quality.

Melody, S. M., Ford, J., Wills, K., Venn, A. & Johnston, F. H. Maternal exposure to short-to medium-term outdoor air pollution and obstetric and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review. Environ. Pollut. 244, 915–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.10.086 (2019).

Gould, G., Harvard, A., Ling, L., Kumar, R. & The PASANZ Smoking in Pregnancy Expert Group. Exposure to Tobacco, Environmental Tobacco Smoke and Nicotine in pregnancy: a pragmatic overview of reviews of maternal and child outcomes, effectiveness of interventions and barriers and facilitators to quitting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17, 2034. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062034 (2020).

Kumar, R., Eftekhari, P. & Gould, G. S. Pregnant women who smoke may be at Greater risk of adverse effects from bushfires. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126223 (2021).

Shah, N. R. & Bracken, M. B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies on the association between maternal cigarette smoking and preterm delivery. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 182, 465–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9378(00)70240-7 (2000).

Evershed, N. & Ball, A. How Australia’s bushfires spread: mapping the east coast fires The Guardian (2020). https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2019/nov/21/how-australias-bushfires-spread-mapping-the-nsw-and-queensland-fires.

NSW Health. Hunter New England, (2024). https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/lhd/Pages/hnelhd.aspx.

NSW Ministry of Health. NSW Mothers and Babies. (2023). (2021). https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/hsnsw/Publications/mothers-and-babies-2021.pdf.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2021 Census all persons QuickStats; Hunter (2021). https://abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/CED121.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2021 Census All persons QuickStats; New England and North West (2021). https://abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/110.

Australian Government, (National Environment Protection Council), National Environment Protection (Ambient Air Quality) Measure. https://www.legislation.gov.au/F2007B01142/latest/text (2021).

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Regional population 2016–2021: Population Grid (2022). https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/7e0b4ffd750740f490ae1d1c51ad12d3.

NSW Government. How and why we monitor air pollution (2024). https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/air/air-quality-basics/sampling-air-pollution.

da Silva, A. M. C., Moi, G. P., Mattos, I. E. & de Hacon, S. Low birth weight at term and the presence of fine particulate matter and carbon monoxide in the Brazilian Amazon: a population-based retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 14, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-309 (2014).

Abdo, M. et al. Impact of Wildfire smoke on adverse pregnancy outcomes in Colorado, 2007–2015. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193720 (2019).

NSW Goverment. NSW Perinatal Data Collection (PDC) Reporting and Submission Requirements from 1 January 2016. (2015). https://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ActivePDSDocuments/PD2015_025.pdf.

Arabzadeh, H. et al. The maternal factors associated with infant low birth weight: an umbrella review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 24, 316. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-024-06487-y (2024).

Holstius, D., Reid, C. & Jesdale, B. Morello-Frosch, R. Birth Weight following pregnancy during the 2003 Southern California wildfires. Environ. Health Perspect. 120 https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1104515 (2012).

STATA. StataCorp LLC. 16. https://www.stata.com/ (2020).

O’Donnell, M. H. & Behie, A. M. Effects of wildfire disaster exposure on male birth weight in an Australian population. Evol Med Public Health 2014, 344–354. https://doi.org/10.1093/emph/eov027 (2015).

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Children. (2022). https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/australias-children/contents/health/birthweight.

Gage, T. B., Fang, F., O’Neill, E., DiRienzo, G. M. & Education Birth Weight, and infant mortality in the United States. Demography. 50, 615–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0148-2 (2012).

World Health Organization. WHO global air quality guidelines. Particulate matter (PM 2.5 and PM 10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. (2021). https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/345329/9789240034228-eng.pdf.

Orellanoa, P., Reynoso, J., Quarantac, N., Bardache, A. & Ciapponi, A. Short-term exposure to particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and ozone (O3) and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Int. 142 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105876 (2020).

European Commission. EU Air Quality Standards (2023). https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/air/air-quality/eu-air-quality-standards_en.

United States Enviromental Protection Agency. Timeline of Particulate Matter (PM) National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS), (2024). https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/timeline-particulate-matter-pm-national-ambient-air-quality-standards-naaqs.

United Kingdom Government; Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs. Particulate matter (PM10/PM2.5), (2024). https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/air-quality-statistics/concentrations-of-particulate-matter-pm10-and-pm25#:~:text=The%20Environmental%20Targets%20(Fine%20Particulate,Population%20exposure%20to%20PM2.

Sequi-Canet, J. et al. Maternal factors associated with smoking during gestation and consequences in newborns: results of an 18-year study. J. Clin. Translational Res. 8, 6–19 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Nil.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MB, JA, EN, LZ, CM were a team throughout the design, completion and writing of this manuscript. RK, GG, NR were supervisors throughout. Providing feedback, assistance in editing and guidance throughout the process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Birtill, M., Amos, J., Nash, E. et al. Effects of PM2.5 exposure during high bushfire smoke days on birthweight and gestational age in Hunter New England, NSW, Australia. A study on pregnant people who smoke and don’t smoke. Sci Rep 14, 27980 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78199-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78199-4