Abstract

Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) in the Ross Sea region are believed to spawn predominantly in the northern parts of the Ross Gyre during the austral winter with fluctuations in their recruitment observed. This Lagrangian modelling study attempts to explain these fluctuations and shows how sea-ice drift impacts the buoyant eggs and the overall recruitment of juveniles reaching the Amundsen shelf break. Interannual variations in the Amundsen Sea Low, linked to tropical sea surface temperatures, cause modulations in the sea-ice drift and subsequent recruitment. When the Amundsen Sea Low is weaker, consistent with El Niño conditions, the northward sea-ice drift reduces, and more eggs remain within the Ross Gyre leading to a larger recruitment success. Conversely, recruitment success reduces during La Niña conditions. The sea-ice drift may explain about 80% of the interannual Antarctic toothfish recruitment variability over the period 1975–2016 and is of particular importance during the first year after spawning. These results enable future interannual changes in Antarctic toothfish recruitment success based on remote observations to be anticipated. Our findings suggest that ongoing climate change strengthening of the Amundsen Sea Low, will likely contribute to a long-term toothfish recruitment decline in the Ross Gyre region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni), sold commercially as Chilean Sea Bass, is an exploited fish species of the family Nototheniidae endemic to Antarctic waters1 and a key component of Antarctic ecosystems as predator and prey2,3,4,5,6. Fishing vessels harvest about 4000 tonnes of Antarctic toothfish per year, predominantly in the Ross Sea and Amundsen Sea regions7. Antarctic toothfish can grow to about 2 m long, weigh 150 kg and can reach more than 50 years in age8,9,10. Under the auspices of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), a system of assessments and management rules is in place to manage the fishery and maintain Antarctic toothfish stocks and associated species11. In recent years, additional measures such as the Ross Sea region Marine Protected Area, have been established to provide further management tools for Antarctic toothfish and the ecosystem12,13.

Gaps in the knowledge of Antarctic toothfish life cycle remain due to the remoteness of their habitat, which is covered by sea-ice for most of the year. Adult Antarctic toothfish are found along the continental slope of Antarctica, as well as over seamounts in the northern part of the Ross Gyre. In the Ross and Amundsen Sea regions, the low abundance of juvenile Antarctic toothfish (smaller than 30 cm) along the shelf break and high number of Antarctic toothfish at the time of spawning around seamounts has yielded an early life-stage hypothesis14,15,16, where adult Antarctic toothfish migrate from the shelf break to seamounts to spawn. Spawning occurs during austral winter (July–August), at depths ranging between 1000 and 2000 m, near the seamounts, and under sea-ice14,17,18,19 (Fig. 1). The buoyant eggs of Antarctic toothfish float to the surface where they attach to the underside of sea-ice, which provides access to a prey rich environment, as well as a refuge from predators. Recent data suggest an incubation period of 3–4 months, so hatching aligns with early spring14,17. The larvae then spend about 1–2 years developing as part of the ichthyoplankton community in the upper layers of the water column following the prevailing Ross Gyre circulation before finally recruiting to the Amundsen Sea shelf break14. Later in life, a large fraction of Antarctic toothfish juveniles move to the Ross Sea shelf and, after maturation, then migrate to the adult habitat located on the slope of the Ross Sea region14. A similar recruitment cycle, with spawning near topographic features and an open ocean drift and recruitment back to the continental slope, has also recently been proposed for Antarctic toothfish from the East Antarctic20 and the Weddell Sea21.

(a) Schematic of Antarctic toothfish early life stages from spawning until settlement at the continental shelf in the Amundsen Sea. (b) Geographic context of Antarctic toothfish early life stages over the Ross and Amundsen Sea sector. Black shading reflects the Antarctic continent. Light blue shading indicates sea-ice cover during the winter season, while dark blue shaded regions represent open ocean (sea-ice concentration below 10% during winter season). Red dots illustrate potential spawning locations of Antarctic toothfish within the northern Ross Sea sector around topographic features. Thin black solid contour lines show observed sea-surface height from Cryosat-2 (2011–201622,23) to indicate the large-scale oceanic circulation. Black dashed lines show the Ross Sea region Marine Protected Area. The red shaded area in the Amundsen Sea illustrates the assumed settlement region of juvenile Antarctic toothfish. The purple, green and orange shaded regions and labels illustrate the four early life stages of Antarctic toothfish. The black arrow indicates the assumed pathway between spawning and settlement regions following the large-scale Ross Gyre circulation. The red boundaries in the inset show the study area in relation to Antarctic continent and the Southern Ocean.

Given the current understanding of the life cycle of Antarctic toothfish, sea-ice drift during the egg and larval phase is likely to be a key factor controlling the interannual to long-term recruitment success20,24,25. In the Ross Sea region sea-ice has been expanding over the satellite era26,27,28, from 1979 until 201529,30, and interannual variability of sea-ice through the Amundsen Sea Low has been linked to extratropical processes31,32,33,34,35 and variability of the Ross Gyre36. These studies found that La Niña conditions, characterised by positive sea surface temperature anomalies in the west Pacific and Indian Ocean, drive a stronger Amundsen Sea Low and a stronger cyclonic Ross Gyre circulation.

By using existing knowledge of past variability and trends of sea-ice in the Ross Sea sector driven by the Amundsen Sea Low, we here attempt to relate these physical processes to the recruitment of Antarctic toothfish. Applying this understanding of physical processes and variability to the toothfish life cycle leads to two modes with opposing implications for recruitment (Fig. 2a,b). Primary mode: Eggs and larvae west of the centre of the Amundsen Sea Low will follow a more northward trajectory (purple arrow in Fig. 2a) when the Amundsen Sea Low is stronger compared to when it is weaker (green arrow Fig. 2a). This northward shift during a stronger Amundsen Sea Low is the result of an increased cyclonic circulation with enhanced northwards sea-ice drift and ocean currents. This circulation pattern will carry eggs and larvae further into the open Southern Ocean away from the settlement region compared to periods when the Amundsen Sea Low is weaker (green arrow Fig. 2a). Remaining in the Ross Gyre circulation is considered favourable for recruitment to the Amundsen Sea shelf break, so that a more northward trajectory will therefore result in reduced recruitment as more larvae leave the Ross Gyre. Conversely, a more southward trajectory would enhance the likelihood that larvae remain retained in the Ross Gyre, leading to an increase in recruitment. Secondary mode: This mode will have an opposing effect on larvae and recruitment compared to the primary mode as larvae transition from the west to the east of the Amundsen Sea Low, typically within the first year post spawning (Fig. 2b). This secondary mode will therefore have an impact on larvae spawned in the previous year and until they reach the settlement region. In this secondary mode a stronger Amundsen Sea Low would be favourable for recruitment by increasing the southward drift towards the settlement region and a weaker Amundsen Sea Low is now less favourable for recruitment. These two competing modes complicate our ability to infer links between Antarctic toothfish recruitment and the physical processes. Nevertheless, the primary mode is assumed to dominate over the secondary mode since eggs and early-stage larvae are more strongly affected by sea ice drift and ocean currents before their swimming ability increases and might allow them to counteract unfavourable conditions during the secondary mode. In the first part of the paper we link Antarctic toothfish recruitment to physical indices characterising the climate system driving the Ross Gyre. We then present Lagrangian particle tracking results to simulate recruitment and directly confirm both modes by identifying how the Amundsen Sea Low, and associated physical processes, can impact Antarctic toothfish recruitment.

Proposed physical processes which impact Antarctic toothfish recruitment. (a) Primary mode which acts on eggs and larvae west of the Amundsen Sea Low centre (ASL, blue contour lines). Red dots indicate potential spawning locations of Antarctic toothfish within the northern Ross Sea sector. The green arrow illustrates the assumed trajectory of eggs and larvae during a weaker Amundsen Sea Low in contrast to the purple arrow when the Amundsen Sea Low is stronger. Purple and green circles indicate the assumed pathway of larvae after their first 1 year. The red shaded area in the Amundsen Sea indicates the assumed settlement area of Antarctic toothfish where a weaker Amundsen Sea Low would result in an increased recruitment. The conceptual impact flow in relation to the strength of the Amundsen Sea Low when eggs and larvae are west of the centre is outlined below the map, where green (purple) outlines the impact from a weaker (stronger) Amundsen Sea Low. (b) Secondary mode which would act on larvae after their first year when they have travelled to the east of the Amundsen Sea Low centre where a stronger Amundsen Sea Low would increase recruitment and competes against the primary mode. Black shading reflects the Antarctic continent. Light blue shading indicates sea-ice cover during the winter season, while dark blue shaded regions indicate open ocean (sea-ice concentration below 10% during winter season). Thin black contour lines show observed sea-surface height from Cryosat-2 (2011–201622,23) to indicate the large-scale oceanic circulation. Black dashed lines show the Ross Sea marine protected area. Thick grey contour reflects the 1000m iso-bath. Green and purple squares and triangles at the bottom are used to identify the individual years in the recruitment timeseries (Fig. 3a) when this mode is active.

Results

Toothfish recruitment and climate drivers

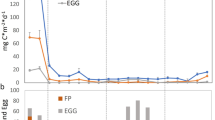

The toothfish recruitment timeseries shows positive recruitment anomalies between 1974 and 1979, 1990–1992 and for 2013, while the 19-year period from 1994 to 2012 is characterised by negative recruitment anomalies (colour coded bars in Fig. 3a). The presence of long-term decadal variability hinders, at this stage, a clear assessment of overall recruitment trends and motivates the focus on interannual recruitment variability and links to physical processes.

(a) Normalised Antarctic toothfish recruitment anomaly (color-coded bars, left axis) and its links to climate processes. July-December anomalies for sea level pressure anomaly (blue line and symbols) for the Amundsen Sea Low (ASL, area-average over blue box in (b) and (c)), tropical sea surface temperatures (SSTs) (orange symbols) and sea-ice concentrations (grey lines and symbols, area-average over red box in (b) and (c)). Note sea surface temperatures and sea-ice cover share the same y-axis on the right. Filled color-coded circles indicate where the sign of the climate process aligns with the sign of the recruitment anomaly following the primary mode. Blue diamonds, as part of the Amundsen Sea Low sea level pressure timeseries, show when the secondary mode can explain the sign of toothfish recruitment anomalies. Open color-coded circles show where the sign of the anomalies between both indices does not align with the primary and secondary mode. Years highlighted by green/purple squares at the bottom represent the highest and lowest 15th percentile of recruitment anomalies. Years highlighted by green and purple triangles at the bottom indicate years where the state of the Amundsen Sea Low can explain the sign of the toothfish recruitment anomaly of toothfish larvae spawned during the previous year (secondary mode). End-member composite anomalies for ‘high’ recruitment minus ‘low’ recruitment years for detrended (b) modelled sea-ice concentration, (d) meridional wind anomalies and (f) modelled meridional sea-ice velocity to confirm the existence of the primary mode. Grey contours indicate sea level pressure anomalies for the composite (contour interval 100hPa, solid lines are positive anomalies). (c, e, g) Secondary mode composite anomalies for years where anomalies for Amundsen Sea Low are positive and recruitment anomalies of the previous year are negative (purple triangles in a) minus years where anomalies for Amundsen Sea Low are negative and recruitment anomalies of the previous year are positive (green triangles in a). Black contour lines show observed sea-surface height from Cryosat-2 (2011–201622,23) to indicate the large-scale oceanic circulation. Thick orange contour reflects the 1000m iso-bath and red shaded area in the Amundsen Sea indicates the assumed settlement area of Antarctic toothfish.

First, we test for the primary mode (Fig. 2a) and verify if the sign of anomalies between Amundsen Sea Low and recruitment covary. We find for 25 of the 42 years for which we have recruitment anomalies (i.e., 59% of those years), the sign of the anomalies agrees (full blue circles, Fig. 3a). Both timeseries are significantly correlated with r = 0.79 (p = 0.05, n = 25) for the first mode, with a weaker but still significant correlation when using all 42 years from the timeseries (r = 0.34, p = 0.05, n = 42).

Next, we test if, for the 17 ‘disagreement’ years the secondary mode (Fig. 2b) applies where the Amundsen Sea Low might have had an impact on Antarctic toothfish recruitment via eggs spawned during the previous year. For 9 of the 17 years, the sign of the anomalies align (blue diamonds) and the secondary mode would explain the recruitment anomalies. The correlation coefficient for the second mode for those years is r = − 0.67 and deemed significant (p = 0.05, n = 9). That leaves 8 years of the 42 years unexplained for which we have recruitment anomalies (open blue circles).

Teleconnections between tropical sea surface temperatures and the strength of the Amundsen Sea Low via Rossby waves trains have been described by several studies31,34,35. We found that, for 22 of the 42 years (52%), the sign of the tropical sea surface temperatures anomalies (50–170° W, 0–10° S) aligns with the recruitment anomaly following the primary mode (full orange circles). Both timeseries show a correlation coefficient of r = − 0.75 which is deemed significant (p = 0.05, n = 22). For 9 of these 22 years (64%), the sign of the anomalies aligns with the highest and lowest 15th percentile recruitment years, suggesting a stronger impact for the ‘extreme’ recruitment years. Only for 8 of the 25 years (33%) where the state of the Amundsen Sea Low with the primary mode can explain recruitment, tropical sea surface temperatures anomalies show the opposite sign to the Amundsen Sea Low anomalies (open orange circle).

We note that previous studies also pointed out co-variability between the strength of the Amundsen Sea Low and sea-ice cover (grey line) in the Ross Gyre31,34,35, where a weaker Amundsen Sea Low is associated with less sea-ice cover in the northern Ross Gyre and vice versa. Consequently, for 23 years of the 42 years (54%), anomalies between sea-ice and recruitment align following the primary mode (full grey circles), with a significant (p = 0.05, n = 23) negative correlation of r = − 0.71 between both timeseries.

Our recruitment forecasting suggests (grey hashed bars, noting that the magnitude is arbitrarily set to ± 0.2 for visualisation purposes) positive recruitment anomalies for 2016–2019 and negative anomalies for 2020–2021, based on the observed state of the Amundsen Sea Low. Hindcasting recruitment anomalies prior to 1974 is also possible, but these hindcasted recruitment values cannot be retrospectively verified since they exceed the lifetime of Antarctic toothfish (~ 50 years) where this age class cohort becomes diminishingly small.

Further evidence for the existence of the primary mode (Fig. 2a) is provided through end-member composite anomalies for the highest and lowest 15th percentile recruitment years (high minus low recruitment years, green and purple squares in Fig. 3a) for sea-ice cover (Fig. 3b), sea surface pressure, meridional wind (Fig. 3d), and meridional sea-ice velocity (Fig. 3f). These composite anomalies allow identification of co-variability in relation to recruitment independently from the primary mode. The composite anomalies show a weaker Amundsen Sea Low in ‘high’ recruitment years (solid grey contour lines), as well as lower sea-ice cover along the northern boundary of the Ross Gyre to west of the Amundsen Sea Low centre anomaly. The reduced sea-ice cover in this region is a consequence of reduced northward winds and sea-ice velocities, which keeps the sea-ice more consolidated in the south in form of thicker pack ice. To the east of the Amundsen Sea Low centre, east of 120° W, the opposite behaviour is seen, as reduced southward winds and southward sea-ice velocity (shown as positive anomalies) lead to an expansion and increase in sea-ice cover.

After having demonstrated the conceptual links of the primary mode, we now focus on the secondary mode. Here, we construct composite anomalies again, but this time for years where the Amundsen Sea Low anomalies are positive and recruitment anomalies for the previous year are negative (purple triangles in Fig. 3a) minus years where the Amundsen Sea Low anomalies are negative and recruitment anomalies for the previous year are positive (green triangles in Fig. 3a). Co-variability between Amundsen Sea Low and recruitment, following the secondary mode, is a requirement for this composite but still allows demonstration of how related variables (sea-ice concentration, meridional wind, meridional sea-ice drift) respond to changes in Amundsen Sea Low during these years. In the way the composite is formed the anomaly patterns should align with the previous composite anomalies (Fig. 3b,d,f), used to confirm the primary mode, but would imply an opposing recruitment response to the primary mode. The composite anomaly pattern (Fig. 3c,e,g) generally follows the pattern from the primary mode, providing further confidence for the underlying process and results are not a subsample artifact. For the secondary mode, we observe that the centre of the Amundsen Sea Low anomaly (grey contour lines) is shifted to the south-west, which causes a westward shift in related anomalies (e.g., sea-ice concentration).

Simulating Antarctic toothfish recruitment

In the following two sections we use Lagrangian methods to directly simulate Antarctic toothfish recruitment and provide evidence for our proposed links to the state of the Amundsen Sea Low (primary and secondary mode).

Ocean sea-ice advection during the egg and early larval phases (primary mode)

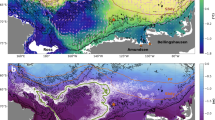

Each winter season (15th July–15th October) between 1970 and 2018, ~ 300.000 passive particles, simulating Antarctic toothfish eggs, were released at depth over the assumed spawning locations (Figs. 1b and S1b). These particles were then tracked for to 2 years, recording the presence of sea-ice, and sea-ice and ocean velocities encountered during their journey. Further details are provided in the Methods section. Using particles released during one of the highest and lowest 15th percentile recruitments years (green and purple squares in Fig. 3a) an end-member composite anomaly has been constructed to demonstrate the difference in the sea-ice ocean state and its impact on the simulated recruitment (Fig. 4).

Lagrangian diagnostics for end-member composites (‘high’ recruitment year minus ‘low’ recruitment year to confirm the primary mode). Ratio between sea-ice and ocean conditions which toothfish eggs encounter (a, b) over the first 100 days and (c, d) 1 year for ‘low’ recruitment and ‘high’ recruitment years, respectively. (e) Mean velocity vectors which eggs and larvae encountered over the first 100 days and 1 year for ‘low’ recruitment and ‘high’ recruitment years. Velocity vectors are separated into oceanic (blue) and sea-ice (light blue) velocity components. Net velocity is shown by the color-coded symbols. Heatmap composite anomalies (‘high’ recruitment minus ‘low’ recruitment years): (f) 100 days, (g) 1 year, (h) 1.5 years and (i) 2 years after spawning. Positive (negative) anomalies in (f–i) indicate an elevated probability for eggs/larvae in this region in ‘high’ (‘low’) recruitment years. The mean location over all particles in the ‘high’ (‘low’) recruitment ensemble is shown by green (purple) diamonds. Orange box in (g–i), the target region, is used to measure the recruitment success. (j) Lagrangian recruitment success (in %) for ‘high’ recruitment (green bar) and ‘low’ recruitment (purple bar) years.

During ‘low’ recruitment years (purple squares in Fig. 3a) particles encounter sea-ice about 65% of the time over the first 100 days after spawning, while particles in ‘high’ recruitment years (green squares in Fig. 3a, see also Table S1 for the selected years) encounter sea-ice only 58% of the time (Fig. 4a,b). These results match the negative sea-ice composite anomalies in the northern Ross Gyre presented in Fig. 3b, as particles move through this region. Over the first year and beyond, this sea-ice concentration separation diminishes as more particles during ‘low’ recruitment years are being swept into the open Southern Ocean and encounter less sea-ice over time than those particles which stay within the Ross Gyre (Fig. 4c,d). This is also evident in averaged velocities which particles encounter over the first 100 days and 1 year (Fig. 4e). In ‘low’ recruitment years, eggs on average encounter about ~ 0.4 cm/s stronger northward sea-ice drift compared to eggs in ‘high’ recruitment years, which equates to a ~ 35 km northward displacement over the first 100 days on average. This northward sea-ice related shift increases the likelihood that particles leave the Ross Gyre, subsequently are carrying them into the wider the Southern Ocean. In this case ocean advection then contributes to another ~ 95 km (~ 1.1 cm/s) northward displacement. Adding sea-ice drift there is therefore a total northward displacement of ~ 130 km relative to ‘high’ recruitment years over the first 100 days with adverse implications for recruitment success. In the ‘high’ recruitment years, the lower northward sea-ice velocity over the first 100 days increases the likelihood that eggs stay within the Ross Gyre boundaries, thereby avoiding additional northward oceanic displacement from open Southern Ocean currents. Within the first year the large 100 day advection difference reduces, and velocity vectors look more similar between ‘high’ and ‘low’ recruitment years. Nevertheless, on average, particles seeded during ‘high’ recruitment years are found about 70 km further south and about 170 km further west than particles during ‘low’ recruitment years after their first year.

This separation is also demonstrated in heatmap composite anomalies (‘high’ minus ‘low’ recruitment years, Fig. 4f–i). We observe a north–south dipole pattern emerging over the first 2 years, where positive anomalies indicate a higher likelihood for toothfish presence during ‘high’ recruitment years and negative anomalies a higher likelihood for toothfish presence during ‘low’ recruitment years. This anomaly pattern implies that more toothfish on average stay within the Ross Gyre boundaries (black contour lines) during ‘high’ recruitment years which increases the chance that toothfish after one year drift south towards the settlement region (red shaded area) and do not continue east toward the Antarctic Peninsula. This switch in direction becomes very apparent after one year (Fig. 4g), where positive anomalies propagate towards the settlement region. Despite this enhanced southward pathway in ‘high’ recruitment years, the majority of particles continue to drift eastwards away from the settlement region but generally further south compared to the ‘low’ recruitment years (color-coded diamonds).

Counting the number of particles which enter the target region (orange box in Fig. 4f–i) within the first year relative to the overall number of seeded particles provides a proxy for recruitment. We find that simulated recruitment success is reduced during ‘low’ recruitment years compared to ‘high’ recruitment years (Fig. 4j). During ‘high’ recruitment years recruitment rate (~ 6%) is on average more than twice the rate during ‘low’ recruitment years (~ 2.5%), providing evidence for our proposed primary mode. The modelled recruitment co-varies with the observed recruitment for these high and low recruitment years with a correlation coefficient of r = 0.54 which is deemed significant (n = 14, p = 0.05). However, co-variability for the entire length of both records is not significant.

Ocean sea-ice advection during the second-year post spawning (secondary mode)

Having demonstrated the impact of the primary mode on Antarctic toothfish recruitment, we turn our attention to the secondary mode, which would affect toothfish during their second year of life, when larvae have been carried to the east of the Amundsen Sea Low centre. The heatmap composite anomalies for when the Amundsen Sea Low is stronger minus years when the low is weaker are shown in Fig. 5 (see Table S1 and Fig. 3a for the selected years) follow our proposed secondary mode. Positive anomalies in the heatmaps indicate a higher likelihood for particles in this region during a stronger Amundsen Sea Low and vice versa for negative anomalies. We observe more positive anomalies closer to our target region (orange box) than negative anomalies within the first year (Fig. 5a–c), highlighting an enhanced southward advection of particles during years when the Amundsen Sea Low is stronger. Consequently, recruitment success—the number of particles which reach the target region—is on average 35% higher during years when the Amundsen Sea Low is stronger compared to the rate during weaker Amundsen Sea Low years (Fig. 5e), providing evidence for our proposed secondary mode.

Lagrangian diagnostics for end-member composites in relation to the state of the Amundsen Sea Low showing the secondary mode on toothfish larvae advection during their 2nd winter. Heatmap composite anomalies (Amundsen Sea Low strong minus Amundsen Sea Low weak): (a) 50 days, (b) 100 days, (c) 200 days and (d) 1 year after release over the red box in the north eastern part of the Ross Gyre. Positive (negative) anomalies in (a–d) indicate an elevated probability for larvae in this region when the Amundsen Sea Low is ‘strong’ (‘weak’). The mean location over all particles in the ASL ‘strong’ (‘weak’) ensemble is shown by green (purple) diamonds. Orange box in (a–d), referred to as target region, is used to measure the recruitment success. (j) Lagrangian recruitment success (in %) for Amundsen Sea Low ‘strong’ (green bar) and Amundsen Sea Low ‘weak’ (purple bar) years.

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we provided a physical explanation for the year-to-year variations in Antarctic toothfish recruitment over the Ross Sea and Amundsen Sea regions, and related their recruitment to the state of the Amundsen Sea Low and associated changes in the oceanic and sea-ice advection. We proposed two competing modes accounting for the differing impacts of ocean sea-ice advection on recruitment for toothfish found to the west and east of the Amundsen Sea Low, noting that toothfish will pass through both regions in their early life history (Fig. 2a,b).

We find that the primary mode, when toothfish eggs and larvae are west of the Amundsen Sea Low centre, can explain about 60% of the sign of the 42-year recruitment anomaly record. During this early life stage (~ 1st year post spawning), a weaker Amundsen Sea Low is advantageous for recruitment success as more toothfish eggs and larvae stay within the boundary of the Ross Gyre. On the other hand, in years when the Amundsen Sea Low is stronger ocean sea-ice advection carries toothfish eggs on average about ~ 130 km further north into the open Southern Ocean. This more northward trajectory reduces the likelihood for recruitment back to the shelf break of the Amundsen Sea. The secondary mode, which applies roughly one year after post-spawning when larvae have travelled east of the Amundsen Sea Low centre, can explain a further ~ 20% of the sign of the recruitment anomaly. During this period, a stronger Amundsen Sea Low associated with a more southward ocean sea-ice advection increases the chance for recruitment to the shelf break of the Amundsen Sea, in contrast to a weaker Amundsen Sea Low where eastward propagation becomes prevalent.

Our results highlight the major role the primary mode plays during the early toothfish life stage, dominating Antarctic toothfish recruitment variability. This fits with our expectation that ocean sea-ice advection during the very early life stage is key, when toothfish eggs and larvae are considered as passive drifters, before their swimming capability increases14 and toothfish might become less reliant on favourable ocean sea-ice conditions for recruitment to the shelf break. In that regard the associated uncertainties around the secondary mode are larger as toothfish have become more mobile at that point in time. However, favourable ocean currents might still be an advantage for recruitment as more toothfish would reach the shelf break earlier as a result of lower physiological energy consumption. Our results do not suggest that compounding favourable Amundsen Sea Low conditions of the primary and secondary mode would necessarily result in a more positive recruitment, compared to using both modes independently as recruitment predictors. This result points to non-linear bio-physical factors (for example, food availability, presence of predators, ocean sea-ice advection, spawning region, spawning variability) from the time of spawning onwards to control the overall recruitment14,37,38. Nevertheless, our results suggest that for some years physical processes in the form of ocean sea-ice advection contribute significantly to the recruitment success.

Significant Antarctic toothfish larval phase knowledge gaps remain, which can impact recruitment prediction. For example, recruitment success would be increased if larvae did not follow sea-ice but ocean currents, or started swimming actively towards the coast24. It remains unknown how Antarctic toothfish larvae interact with sea-ice and if this association changes as they grow and develop their swimming ability further impacting their recruitment success and associated timescales. In addition, the present Lagrangian results also do not consider natural mortality, another factor for uncertainty. These combined uncertainties limit our ability to predict the actual magnitude of the recruitment success, beyond predicting only the sign of the anomaly and basically identifying ‘good’ and ‘bad’ recruitment years. Certainly, a better understanding of the toothfish behaviour and natural mortality within the first year and post hatching, when larvae are at the north-eastern edge of the Ross Gyre, would likely improve the accuracy of future toothfish recruitment modelling.

At present our simulations, while able to explain part of the year-to-year recruitment variability, suggest that ~ 95% of toothfish eggs/larvae would not settle in the Amundsen Sea, as they leave the Ross Gyre and continue their journey east towards the Antarctic Peninsula. This raises the question of how such a small percentage would be able to sustain a population if this is the primary recruitment pathway or if further settlement regions exist further east. The Bellingshausen Shelf and Antarctic Peninsula are known Antarctic toothfish habitats39 with small (< 50 cm) toothfish caught in these regions40 and Antarctic toothfish genetics have shown a strong spatial connectivity41.

Links between the tropics and the strength of Amundsen Sea Low and sea-ice variability have been identified by a number of interannual time scales studies e.g,.31,34,35. Furthermore, a long-term strengthening of the Amundsen Sea Low over past decades has also been observed42, with an associated increase in sea-ice cover over the Ross Gyre43. These positive trends until 201544 might have contributed to the overall observed recruitment decline (1975–2016). It will be interesting to evaluate in future studies how toothfish recruitment developed over the most recent years, which were characterised by substantial sea-ice loss in the Ross Sea region30,44 and the establishment of the large-scale Ross Sea region marine protected area that is located primarily where toothfish juveniles reside45. Furthermore, climate models also predict a further decline in sea-ice cover as anthropogenic global warming progresses46,47. Arguably, this will have widespread implications on the marine ecosystem, and particularly for toothfish and other species that have a strong association with sea-ice. It has been shown that a lack of sea-ice increases Antarctic toothfish recruitment24, while not taking other services that sea-ice provides for toothfish eggs and larvae (e.g., food, shelter) into account.

In conclusion, the present study has demonstrated that the Amundsen Sea Low and associated ocean sea-ice advection can be used as a proxy for Antarctic toothfish recruitment. Unfortunately, Antarctic toothfish recruitment has an unavoidable lag of 5 years until enough catch-at-age data are available for a toothfish cohort to adequately estimate its recruitment strength (year class strength). We speculate that modern data science techniques, and more realistic ocean sea-ice simulations in combination with a better understanding of the early phases of Antarctic toothfish life cycle, would allow for real-time estimates of Antarctic toothfish recruitment. Furthermore, forecasts and projections of Amundsen Sea Low, sea-ice and ocean currents would even allow for future forecasting of Antarctic toothfish recruitment, enabling more forward-looking toothfish management. It is hoped that the findings from the present study for the Ross and Amundsen Sea regions may translate to other toothfish populations around Antarctica which have shown similar recruitment strategies (e.g., Antarctic toothfish from East Antarctica20).

Methods

Hydrodynamic model

The hydrodynamic model is based on Nucleus for European Modelling of the Ocean (NEMO) 3.648 to simulate the oceanic state and is coupled to Community Ice CodE (CICE) 5.149 to simulate sea-ice. The model uses a global configuration which is referred to as GO650 with grid sizes of 0.25° on a tripolar model grid with 75 vertical z-levels. The horizontal model resolution in the study areas is about 17 km and considered eddy-permitting. The hindcast modelling has been forced using Japanese 55-Year Reanalysis Driving Ocean (JRA-55-DO51,52) v1.5 atmospheric reanalysis data from 1958 to 2022 with initial conditions for the ocean (i.e. temperature and salinity) based on EN453. The JRA-55-DO dataset provides 3 hourly atmospheric data on a global 1.25° × 1.25° grid from 1958 onward. The model does not resolve explicitly tides nor iceshelf cavities but includes a tidal mixing parameterization.

Toothfish recruitment data

The toothfish recruitment data used in the present study were generated with the stock assessment model for Ross Sea region Antarctic toothfish54. This model is implemented with the software package CASAL55. Annual recruitment values can be derived with the assessment model if the model estimates a year class strength (YCS) value for the previous year (e.g., recruitment in 2012 can be computed if the model estimates a YCS value for 2011). The latest assessment model for Ross Sea region Antarctic toothfish54 estimated YCS values for the years 2003–2015, thereby allowing for the calculation of recruitment values for 2004–2016. No YCS estimates could be generated past 2015, because there were not enough years of catch-at-age data to adequately estimate a YCS for the toothfish cohorts born after 2015. For the present study, the latest assessment model for Ross Sea region Antarctic toothfish54 was extended to start in 1975, which allowed for the estimation of YCS values starting in 1974 and, therefore, for the estimation of recruitment values for the years 1975–2016 (42-years). The choice of 1974 was guided by the availability of adequate information on the cohorts only seen at older ages (i.e., aged 25 and above from 2000)56,57. Note a one-year shift back in time has been applied to the entire recruitment timeseries in this study to align the recruitment estimates in time with the environmental conditions these eggs would have encountered after spawning. Recruitment anomalies for this study have been obtained by normalising the actual recruitment values to 0 and 1 and subsequently subtracting the mean value over the 42 years.

Observed sea-ice velocity, ocean velocity and sea surface height

To validate modelled sea-ice velocities, the remotely sensed daily Polar Pathfinder product58 was used. This dataset has a 25km horizontal resolution and covers the period from 1978 onward. Observed ocean geostrophic velocities are derived from AVISO59, which covers the period from 1993 onward. Sea surface height observations are based on Cryosat-2 data processed for 2011–201622,23, where a lead detection algorithm has been applied to estimate sea-surface height during winter season when sea-ice is present. These datasets have been used to validate the hydrodynamic model (see Model evaluation section below).

Linear trends for the period 1974 to 2022 have been removed before computing anomalies and composites for physical quantities (sea level pressure, sea surface temperature, modelled sea-ice and winds) used for Fig. 3 to eliminate long-term climate trends in the Southern Ocean and maintain the focus on interannual variability.

Significance test

To test the robustness of our results a two-side Student’s t-test has been conducted, where the correlation coefficients and p values have been diagnosed and significance evaluated in relation to the sample size. A significance level p = 0.05 has been used to assess significance.

Lagrangian modelling

To simulate the dispersal of toothfish eggs and larvae over time Parcels60, a numerical particle tracking tool, was used. Here, modelled ocean and sea-ice velocities as 5-daily averages from 1970 to 2019 from the hindcast were employed to advect the virtual toothfish eggs and larvae. A 4th order Runga-Kutta time stepping scheme was used with a 1h time step. No additional random walk was applied to particle trajectories.

Primary mode—the climatic state and its impact on egg and larvae dispersal during their first year

To demonstrate the effect of the primary mode on toothfish recruitment, passive particles were continuously released between 15th July and 15th October (total of 291.226 per year) over the potential spawning locations every year from 1974 to 2016. Virtual toothfish were tracked for 2 years and along their journey recorded their geographic location, and ocean and sea-ice velocities. All geographic locations north of the Antarctic Shelf break within the Ross Gyre and water depths between 1000 and 2500m, based on ETOPO161, were used as potential spawning regions (blue dots in Fig. S1b). The high-resolution bathymetry dataset, with a 1-min horizontal resolution, ensures that subsurface features such as seamounts are captured. Particles were released 50 m above the ETOPO1 depth or at least at the maximum depth of the model. The virtual eggs floated to the surface at 0.311 cm/s based on buoyancy estimates18. Eggs reached the surface within 3.5 and 9.5 days and were advected with ocean currents during that time. At the surface eggs were advected with modelled sea-ice velocities when sea-ice concentrations were above 10%, otherwise modelled surface ocean currents were employed. Recent findings suggest that the buoyant eggs hatch after about 100 days, marking the end of the passive stage as larvae slowly develop their swimming capability. No active swimming was implemented into the Lagrangian particle tracking to focus on physical connectivity. After their first-year post spawning, toothfish larvae only use surface ocean currents, irrespective of sea-ice presence. This behavioural change is based on “best-guess” estimates of previous work24 assuming that Antarctic toothfish larvae develop their swimming capability and lose their strong association with sea-ice. No diurnal vertical movement was used since previous results did not show any substantial impact on the recruitment success.

Secondary mode—the climatic state and its impact on larvae after their first year

To demonstrate the impact of the secondary mode on the toothfish recruitment, passive particles were continuously released between 15th July and 15th December (total of 159.681 per year) over the northeast corner of the Ross Gyre (155° W to 145° W, 65° S to 60° S, red box Fig. 5a–d) every year from 1974 to 2016. This seeding region was chosen as it is the ‘northeast’ corner of the Ross Sea Gyre and close to the location where toothfish are found after 1 year when spawned around seamounts in the Ross Sea region (Fig. 4g). Consistent with the primary mode, these virtual toothfish (with age of > 1 year) only use surface ocean velocities for advection and have no association with sea-ice.

Modelled recruitment success

To quantify the recruitment success in these Lagrangian simulations a simple counting scheme was used. All particles which entered the target region (145° W to 115° W, 70° S to 65° S, orange box in Figs. 4 and 5) within 1 year after spawning are counted to obtain a modelled recruitment measure. The box is north of the shelf break, the actual settlement region, but we assume that particles which are that close to the shelf break would settle to this region. For the primary and secondary mode, particles seeded during these identified years (Table S1) were employed to estimate the recruitment success between these two end-member ensembles.

Model validation

The hydrodynamic model showed good performance in key oceanic metrics50. With respect to the Ross Sea and Amundsen Sea, the model captures the main features in these regions, namely the Ross Gyre and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, given the observational uncertainties (Fig. S1c–f). Sea surface height and its spatial variations, a measure for upper ocean circulation, showed a good agreement between model and observations. The main feature is the cyclonic Ross Gyre Circulation which is bounded by Antarctic Circumpolar Current to its north. The shape and absolute values varied slightly between model and observations. Obtaining sea-surface height measurement during winter season is difficult and requires complex lead detection algorithms, which is a source of uncertainty in these data products22. The modelled Ross Gyre strength of about 24 Sv falls in the range of observed and modelled estimates ~ 15–30 Sv36,62,63,64. Furthermore, the pattern and magnitude of sea-ice and ocean velocity compared well between observations and model.

We note that modelled sea-ice velocities over the northern part of the Ross Gyre, our key region (red box in Fig. S1e–f), were more zonal than in the observations. Potential reasons for this include ocean sea-ice interactions, since modelled sea-ice velocities showed more fine scale structures than the observations. This zonal sea-ice velocity model bias suggests that the model underestimated the northward sea-ice transport and Lagrangian larvae transport. The consequence is that the effect of the primary mode in the Lagrangian analysis is underestimated since the bias reduced the difference between both end-member ensembles. While the model is only eddy permitting, the model fields and biases are very similar to eddy resolving simulations24.

In addition to the mean values, we demonstrated that the model captured observed interannual-variability over our key region. Area-averages over the northern part of the Ross Gyre showed co-variability between modelled velocities and observed values. The magnitude between observations and modelled metrics differs, but the sign of the anomalies agrees between observations and model with very few exceptions. This suggests that the model does capture observed interannual variability in meridional sea-ice and ocean velocities in the Ross Sea and Amundsen Sea regions.

Data availability

All data within the paper and its Supplementary Information file is available through Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8136851 and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8140856.

References

Gon, O. & Heemstra, P. C. Fishes of the Southern Ocean Vol. 1 (JLB Smith Institute of Ichthyology Grahamstown, 1990).

Ainley, D. G. & Siniff, D. B. The importance of Antarctic toothfish as prey of Weddell seals in the Ross Sea. Antarct. Sci. 21, 317–327 (2009).

Ainley, D. G. et al. Further evidence that Antarctic toothfish are important to Weddell seals. Antarct. Sci. 33, 17–29 (2021).

Queirós, J. P. et al. Antarctic toothfish Dissostichus mawsoni as a bioindicator of trace and rare earth elements in the Southern Ocean. Chemosphere 321, 138134 (2023).

Di Blasi, D. et al. The challenge to observe antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) under fast ice. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 9, 255 (2021).

Pinkerton, M., Bradford-Grieve, J. & Hanchet, S. A balanced model of the food web of the Ross Sea, Antarctica. CCAMLR Sci. 17, 1–31 (2010).

CCAMLR. Report of the fortieth meeting of the scientific commitee, Australia, Tasmania. https://www.ccamlr.org/en/system/files/e-sc-40-rep.pdf (2021).

Horn, P. Age and growth of Patagonian toothfish (Dissostichus eleginoides) and Antarctic toothfish (D. mawsoni) in waters from the New Zealand subantarctic to the Ross Sea, Antarctica. Fish. Res. 56, 275–287 (2002).

Horn, P., Sutton, C. & DeVries, A. Evidence to support the annual formation of growth zones in otoliths of Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni). CCAMLR Sci. 10, 125–138 (2003).

Ainley, D. G., Brooks, C. M., Eastman, J. T. & Massaro, M. Unnatural selection of Antarctic toothfish in the Ross Sea, Antarctica. In Protection of the three poles, 53–75 (2012).

Abrams, P. A. et al. Necessary elements of precautionary management: implications for the Antarctic toothfish. Fish Fish. 17, 1152–1174 (2016).

Brooks, C. M. et al. The Ross Sea, Antarctica: A highly protected MPA in international waters. Mar. Policy 134, 104795 (2021).

Dunn, A., Vacchi, M. & Watters, G. The Ross Sea Region Marine Protected Area Research and Monitoring Plan. CCAMLR document SCCAMLR-XXXVI/20. Hobart, TAS (2017).

Hanchet, S. M. et al. A hypothetical life cycle for Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) in the Ross See region. CCAMLR Sci. 15, 35–53 (2008).

Ashford, J. et al. Does large-scale ocean circulation structure life history connectivity in Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni)?. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 69, 1903–1919 (2012).

Ashford, J., Dinniman, M., Brooks, C., Wei, L. & Zhu, G. Tying policy to system: Does the Ross Sea region marine reserve protect transport pathways connecting the life history of Antarctic toothfish?. Mar. Policy 136, 104903 (2022).

Parker, S. J. et al. Winter spawning of Antarctic toothfish Dissostichus mawsoni in the Ross Sea region. Antarct. Sci. 31, 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102019000282 (2019).

Parker, S. J. et al. Buoyancy of post-fertilized Dissostichus mawsoni eggs and implications for early life history. Fish. Oceanogr. https://doi.org/10.1111/fog.12552 (2021).

Hanchet, S. et al. The Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni): Biology, ecology, and life history in the Ross Sea region. Hydrobiologia 761, 397–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-015-2435-6 (2015).

Mori, M., Mizobata, K., Ichii, T., Ziegler, P. & Okuda, T. Modeling the egg and larval transport pathways of the Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) in the East Antarctic region: New insights into successful transport connections. Fish. Oceanogr. 31, 19–39 (2022).

Soeffker, M. et al. Towards the development of a stock hypothesis for Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) in area 48. Report No.: WG-SAM-18/33 (2018).

Kwok, R. & Morison, J. Sea surface height and dynamic topography of the ice-covered oceans from CryoSat-2: 2011–2014. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JC011357 (2015).

Armitage, T. W. K., Kwok, R., Thompson, A. F. & Cunningham, G. Dynamic topography and sea level anomalies of the Southern Ocean: variability and teleconnections. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 123, 613–630. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017jc013534 (2018).

Behrens, E., Pinkerton, M., Parker, S., Rickard, G. & Collins, C. The impact of sea-ice drift and ocean circulation on dispersal of toothfish eggs and juveniles in the Ross Gyre and Amundsen Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 126, e2021JC017329. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JC017329 (2021).

Mori, M. et al. Using satellite altimetry to inform hypotheses of transport of early life stage of Patagonian toothfish on the Kerguelen Plateau. Ecol. Model. 340, 45–56 (2016).

Holland, P. R. The seasonality of Antarctic sea ice trends. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 4230–4237 (2014).

Parkinson, C. L. & Cavalieri, D. J. Antarctic sea ice variability and trends, 1979–2010. Cryosphere 6, 871–880 (2012).

Turner, J., Hosking, J. S., Bracegirdle, T. J., Marshall, G. J. & Phillips, T. Recent changes in Antarctic sea ice. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 373, 20140163 (2015).

Wang, S. et al. Contribution of the deepened Amundsen sea low to the record low Antarctic sea ice extent in February 2022. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 054002 (2023).

Turner, J. et al. Record low Antarctic sea ice cover in February 2022. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098904 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Tropical teleconnection impacts on Antarctic climate changes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 680–698 (2021).

Clem, K. R., Renwick, J. A. & McGregor, J. Large-scale forcing of the Amundsen Sea low and its influence on sea ice and West Antarctic temperature. J. Clim. 30, 8405–8424 (2017).

Scott Yiu, Y. Y. & Maycock, A. C. On the seasonality of the El Niño teleconnection to the Amundsen Sea region. J. Clim. 32, 4829–4845 (2019).

Purich, A. & England, M. H. Tropical teleconnections to Antarctic sea ice during austral spring 2016 in coupled pacemaker experiments. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 6848–6858 (2019).

Turner, J., Phillips, T., Hosking, J. S., Marshall, G. J. & Orr, A. The amundsen sea low. Int. J. Climatol. 33, 1818–1829 (2013).

Dotto, T. S. et al. Variability of the Ross Gyre, Southern Ocean: Drivers and responses revealed by satellite altimetry. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 6195–6204 (2018).

Fenaughty, J. Geographical differences in the condition, reproductive development, sex ratio and length distribution of Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) from the Ross Sea, Antarctica (CCAMLR Subarea 88.1). CCAMLR Sci. 13, 27–45 (2006).

Fenaughty, J., Eastman, J. T. & Sidell, B. D. Biological implications of low condition factor “axe handle” specimens of the Antarctic toothfish, Dissostichus mawsoni, from the Ross Sea. Antarct. Sci. 20, 537–551 (2008).

Liu, J., Zhu, A., Wang, X., Zhou, X. & Chen, L. Predicting the current fishable habitat distribution of Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) and its shift in the future under climate change in the Southern Ocean. Peerj 12, e17131 (2024).

Seong, G. C. et al. Feeding ecology of Antarctic toothfish, Dissostichus mawsoni in the subarea 88.3 (Bellingshausen Sea and eastern Amundsen Sea) of the Southern Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1240569 (2023).

Maschette, D. et al. Circumpolar sampling reveals high genetic connectivity of Antarctic toothfish across their spatial distribution. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 33, 295–310 (2023).

Raphael, M. N. et al. The Amundsen Sea low: Variability, change, and impact on Antarctic climate. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 97, 111–121 (2016).

Turner, J., Hosking, J. S., Marshall, G. J., Phillips, T. & Bracegirdle, T. J. Antarctic sea ice increase consistent with intrinsic variability of the Amundsen Sea Low. Clim. Dyn. 46, 2391–2402 (2016).

Eayrs, C., Li, X., Raphael, M. N. & Holland, D. M. Rapid decline in Antarctic sea ice in recent years hints at future change. Nat. Geosci. 14, 460–464 (2021).

CCAMLR. Conservation Measure 91-05. Ross Sea region marine protected area. CCAMLR Conserv. Meas 5, 1–17 (2016).

Holmes, C., Bracegirdle, T. & Holland, P. Antarctic sea ice projections constrained by historical ice cover and future global temperature change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097413 (2022).

Roach, L. A. et al. Antarctic sea ice area in CMIP6. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086729 (2020).

Madec, G. and the NEMO System Team. NEMO Ocean Engine Reference Manual, Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8167700 (2023).

Hunke, E. C. et al. CICE: The Los Alamos Sea ice model documentation and software user’s manual version 5.1 LA-CC-06-012. T-3 Fluid Dynamics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory, 675, 15 (2017).

Storkey, D. et al. UK Global Ocean GO6 and GO7: A traceable hierarchy of model resolutions. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 3187–3213. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-3187-2018 (2018).

Kobayashi, S. et al. The JRA-55 reanalysis: General specifications and basic characteristics. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 93, 5–48. https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.2015-001 (2015).

Tsujino, H. et al. JRA-55 based surface dataset for driving ocean–sea-ice models (JRA55-do). Ocean Model. 130, 79–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocemod.2018.07.002 (2018).

Good, S. A., Martin, M. J. & Rayner, N. A. EN4: Quality controlled ocean temperature and salinity profiles and monthly objective analyses with uncertainty estimates. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 118, 6704–6716. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013JC009067 (2013).

Grüss, A., Dunn, A. & Parker, S. Assessment model for Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) in the Ross Sea region to 2020/21. WG-FSA-2021/26. CCAMLR, Hobart, Australia. 20 p. (2021).

Bull, B. et al. CASAL (C++ algorithmic stock assessment laboratory)–User Manual. (Technical Report 127, NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Kilbirnie, Wellington, 2005).

Dunn, A. Assessment models for Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) in the Ross Sea region to 2018/19. WG-FSA-2019/08. CCAMLR, Hobart, Australia, p. 30 (2019).

Grüss, A., Dunn, A. & Parker, S. Updated stock assessment model for the Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) population of the Ross Sea region for 2021. WG-SAM-2021/13 CCAMLR, Hobart, Australia, p. 17 (2021).

Tschudi, M., Meier, W., Stewart, J., Fowler, C. & Maslanik, J. Polar pathfinder daily 25 km EASE-grid sea ice motion vectors, version 4. Boulder: NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center 10 (2019).

Roemmich, D. & Gilson, J. The 2004–2008 mean and annual cycle of temperature, salinity, and steric height in the global ocean from the Argo Program. Progr. Oceanogr. 82, 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.POCEAN.2009.03.004 (2009).

Delandmeter, P. & van Sebille, E. The Parcels v2.0 Lagrangian framework: New field interpolation schemes. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 3571–3584. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-3571-2019 (2019).

Amante, C. & Eakins, B. W. ETOPO1 arc-minute global relief model: Procedures, data sources and analysis. https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/1163 (2009).

Chu, P. C. & Fan, C. An inverse model for calculation of global volume transport from wind and hydrographic data. J. Mar. Syst. 65, 376–399 (2007).

Mazloff, M. R., Heimbach, P. & Wunsch, C. An eddy-permitting Southern Ocean state estimate. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 40, 880–899 (2010).

Nakayama, Y., Timmermann, R., Rodehacke, C. B., Schröder, M. & Hellmer, H. H. Modeling the spreading of glacial meltwater from the Amundsen and Bellingshausen Seas. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 7942–7949 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This project obtained funding from Ministry for Business Innovation and Employment via C01X1710 Ross Ramp, New Zealand Ministry for Primary Industries under project ANT2019/01, C01X1902 Deep South National Science Challenge and ANTA1801 Antarctic Science Platform. We acknowledge the support of NeSI High Performance Computing Facility team, Fisheries New Zealand and from the UK MetOffice collaboration team. We thank very much Ocean Environmental for letting us use their computing resources to estimate Antarctic toothfish recruitment for the present study. We acknowledge the constructive feedback from all three reviewers to help use strengthen our study and increase its impact.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B., S.P., and A.G; methodology, E.B., S.P., and G.R.; investigation, E.B., S.P., A.G., and G.R., writing—original draft preparation, E.B., S.P., A.G., G.R, M.P. and C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Behrens, E., Grüss, A., Pinkerton, M. et al. Tropical teleconnections through the Amundsen Sea Low impact Antarctic toothfish recruitment within the Ross Gyre. Sci Rep 14, 26715 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78248-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78248-y