Abstract

Hereditary spherocytosis (HS) is the most prevalent form of congenital hemolytic anemia, being caused by genetic mutations in genes encoding red blood cell cytoskeletal proteins. Mutations in the ANK1 and SPTB genes are the most common causes of HS.; however, pathogenicity analyses of these mutations remain limited. This study identified three novel heterozygous mutations in 3 HS patients: c.1994 C > A in ANK1, c.5692 C > T, and c.3823delG in SPTB by whole-exome sequencing (WES) and validated by Sanger sequencing. To investigate the functional consequences of these mutations, we studied their pathogenicity using in vitro culture erythroblast derived from CD34 + stem cells. All three mutations lead to the generation of a premature stop codon. Real-time PCR assay revealed that the two SPTB mutations resulted in reduced SPTB mRNA expression, suggesting a potential role for the nonsense-mediated mRNA degradation pathway. For the ANK1 mutation, gene expression was not reduced but was predicted to produce a truncated version of the ANK1 protein. Flow cytometry analysis of red blood cell-derived microparticles (MPs) revealed that HS patients had higher MP levels compared to normal subjects. This study contributes to the current understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying mutations in the ANK1 and SPTB genes in HS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hereditary spherocytosis (HS) is a common inherited red blood cell (RBC) membrane disorder characterized by wide heterogeneity in the severity of both clinical symptoms and genetic patterns1,2,3. It is caused by a deficiency or dysfunction of the RBC membrane cytoskeleton proteins ankyrin, α-spectrin, β-spectrin, protein 4.2, and band 3 protein. These proteins are encoded by the ANK1, SPTA1, SPTB, EPB42 and SLC4A1genes4,5. Defects in one or more of these membrane proteins disrupt the linkage between the phospholipid bilayer and cytoskeleton, altering the red blood cells’ surface area-to-volume ratio, and ultimately leading to spherocytosis with decreased membrane mechanical stability and cellular deformability6,7. These spherocytes are prone to hemolysis in capillaries and are selectively trapped and destroyed by splenic macrophages, resulting in hemolytic anemia5. Weakened vertical linkages between the cytoskeletal proteins and the lipid bilayer, detected in the red blood cell membrane of HS patients, may contribute to the release of microparticles (MPs)8,9. MPs are small extracellular vesicles, released from various blood cell types upon exposure to conditions like oxidative stress, activation, or apoptosis10.

HS is a genetically heterogeneous disorder with diverse presentations. This heterogeneity arises from mutations in ANK1, SPTA1, SPTB, EPB42, and SLC4A1genes, which can differ in frequency and mutation type between populations11,12. Defects in membrane components of HS patients are primarily caused by gene mutations, most commonly following an autosomal dominant pattern12. Mutations in the ANK1 and SPTB genes are the major contributors to HS, followed by mutations in SLC4A111,12. Mutations in SPTA1 and EPB42 are rare globally, with reports in Japanese13and Korean populations12.

The β-spectrin protein is encoded by the SPTB gene, which is located on chromosome 14q23.3. Mutations in the SPTBgene are commonly detected in Korean12,14, northern European15, Chinese16 and Brazilian populations17, which account for 15–30% of HS cases. The SPTBmutations lead to the production of non-functional spectrin or β-spectrin deficiency18. This consequently weakens the linkage between membrane skeleton proteins, a critical factor for erythrocyte integrity, and causes hemolytic anemia in HS patients6.

Ankyrin is encoded by the ANK1gene, which is found on chromosome 8p11.2. The ankyrin protein consists of an N-terminal binding site for band-3, known as a membrane-binding domain, a central region containing spectrin binding domain, and a C-terminal regulatory domain containing a death domain19. ANK1 is one of the major erythrocyte proteins stabilizing the membrane by the high-affinity vertical linkage between the plasma membrane and the underlying spectrin cytoskeleton via band-320,21. The ANK1 mutations appear to be the common cause of HS in Northern European22,23, Japanese24,25, Korean14, Indian26, Italian27 Chinese16,28 populations. ANK1 mutations are mainly autosomal dominant, but some are inherited in an autosomal recessive de novomutational pattern27. The mutation types are primarily frameshift, nonsense, and splice site mutations14. Previous studies have found that the ANK1 mutations increased the osmotic fragility of cells, reduced the stabilities of ANK1 proteins, prevented the protein from localizing to the plasma membrane, and disrupted interaction with SPTB and SLC4A1 28.

Diagnosis of HS relies on a combination of positive family history, clinical features, and the presence of spherocytes in peripheral blood smear29. Additional confirmatory tests may include the osmotic fragility test, autohemolysis test, flow cytometric-based eosin-5-maleimide (EMA) binding test, and protein analysis using gel electrophoresis or mass spectrometry29. Genetic testing analysis of RBC membrane protein genes is emerging as a supportive tool for diagnosis alongside conventional tests3,29,30. Conventional molecular methods for analyzing mutations in the five large RBC membrane protein genes (spanning 40–50 exons) are costly and time-consuming. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology offers a significant advantage by enabling a comprehensive analysis of mutations across all these genes simultaneously30,31. The development of a high-efficiency genome sequencing method such as NGS makes it possible to determine a causative gene in HS. This study aimed to identify mutations in HS patients by focusing on the targeted regions encoding RBC membrane proteins using whole-exome sequencing (WES). We identified three novel disease-causing mutations in SPTB and ANK1. To validate their functional impact, we performed in vitro studies using cultured erythroblast, analyzing cDNA sequences and gene expression levels. Molecular genetic analysis of HS is a crucial tool for confirming diagnosis and elucidating the pathogenesis mechanisms underlying mutations in HS patients.

Results

Clinical features and laboratory findings in HS patients

Three unrelated Thai HS patients were recruited for the study. Their clinical, hematological, and biochemical data are summarized in Table 1. Consistent with HS, prominent laboratory findings included reticulocytosis and hyperbilirubinemia. Blood smears revealed spherocytes and microspherocytes in approximately 50% of RBCs. Two patients (HS01 and HS02) with a history of cholelithiasis had undergone cholecystectomy. All three patients presented with jaundice. None reported a history of splenomegaly or blood transfusion. To rule out other hemolytic conditions, all patients underwent screening for Thalassemia, autoimmune hemolysis, and G6PD deficiency. Hb typing, direct antiglobulin test, and G6PD enzyme activity were all within normal ranges.

RBC red blood cell, HGB hemoglobin, Hct hematocrit, MCV Mean corpuscular volume, MCH Mean corpuscular hemoglobin, MCHC Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, RDW Red cell distribution width, WBC white blood cell, Plt platelet, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase.

Increased RBC-derived MPs in HS patients

The level of circulating RBC-derived MPs was quantified by flow cytometry using binding to phosphatidylserine and the erythroid-specific marker CD235a (Glycophorin A). RBC-derived MPs were identified within the double-positive cell population for CD235a and Annexin V (Fig. 1). HS patients displayed elevated levels of MPs compared to healthy subjects (6,378.62 ± 1,157.81 vs. 3,291.09 ± 432.59 /µL; p = 0.012).

Levels of red blood cell (RBC)-derived microparticles (MPs). (A) Gating strategy for MPs based on forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) properties, with a size range of 80 nm–1.32 μm (the red rectangle in (A). The gated MPs were analyzed using Annexin V (y-axis) and CD235a-PE (x-axis), where double positivity identifies RBC-derived MPs (the upper right quadrant in (B) and (C). Representative data of RBC-derived MPs for normal subjects (0.3%) and HS patients (14.1%) are shown in figure B and C, respectively. As shown in (D), the absolute number of RBC-derived MPs was significantly higher in HS patients than in healthy subjects.

Increased expansion of cultured erythroblasts from HS patients

Erythroblast expansion in cultured cells isolated from three normal controls and three HS patients was determined by calculating the fold change in total cell number between day 8 and day 14 (Fig. 2). Erythroblasts from HS patients exhibited a significantly higher expansion rate compared to normal controls (10.6 ± 0.74 vs. 4.03 ± 0.52 fold, p = 0.0002).

WES

WES yielded a high mapping rate (> 99.8%) of DNA sequences to targeted regions. Subsequent analysis focused on the five HS-associated genes (ANK1, SPTB, SPTA1, SLC4A1, and EPB42). WES identified 69, 71, and 74 potential mutations in HS01, HS02 and HS03, respectively. Variant annotation and effect prediction using the SnpEff tool identified 3 causative variants (one in each patient), namely c.5692 C > T and c.3823delG in the SPTB gene and c.1994 C > A in the ANK1 gene. All three novel variants with high predicted impact were assessed for pathogenicity using established criteria (Table 2). Following Clinvar analysis, we excluded all benign/likely benign variants. This analysis identified novel variants for HS patients, including two in the SPTB gene and another in the ANK1 gene. None of these three variants were found in Clinvar or the existing literature.

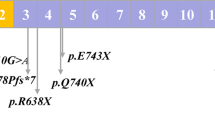

Table 2 details the molecular characterization and predicted pathogenicity of the three novel variants analyzed using bioinformatic tools. We identified two nonsense mutations: c.5692 C > T in exon 26 of the SPTB gene and c.1994 C > A in exon 17 of the ANK1 gene. Additionally, a frameshift mutation caused by a single base pair deletion (c.3823delG) was detected in exon 17 of the SPTB gene. All these variants were inherited in a heterozygous pattern and predicted to be pathogenic as they are likely to lead to protein truncation due to a premature stop codon.

Sanger sequencing analysis of novel SPTB and ANK1 mutations in gDNA and cDNA

To confirm the accuracy of the three potentially significant variants identified by WES, Sanger sequencing was performed on both genomic DNA (gDNA) and cDNA (Fig. 3). gDNA was extracted from whole blood EDTA samples collected from the patients. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA isolated from cultured erythroblasts derived from CD34 + cells. Consistent with the gDNA sequencing results, Sanger sequencing of the SPTB and ANK1 genes revealed heterozygous peaks for the two nonsense mutations in both gDNA and cDNA sequences. Moreover, Sanger sequencing of both gDNA and cDNA from the patient with the c.3823delG variant revealed a single base pair deletion of Guanine (G), resulting in a frameshift mutation.

Sanger sequencing analysis of gDNA and cDNA for mutations in ANK1 (c.1994 C > A) and SPTB (c.5692 C > T and c.3823delG). Consistent heterozygous nucleotide substitutions causing nonsense mutations were observed in both gDNA and cDNA sequences for ANK1 (c.1994 C > A) and SPTB (c.5692 C > T). The variant c.3823delG exhibits a frameshift mutation pattern in both gDNA and cDNA sequences.

Decreased SPTB mRNA expression in HS patients

qRT-PCR was used to measure the mRNA expression levels of the ANK1 and SPTB genes in cultured erythroblasts and then compared to mRNA expression in normal erythroblasts. The c.5692 C > T and c.3823delG variants in the SPTB gene displayed a significant reduction in mRNA expression (over 80%) compared to normal erythroblasts (Fig. 4). In contrast, the c.1994 C > A mutation did not correlate with the mRNA expression level of the ANK1 gene.

Discussion

WES in combination with bioinformatic analysis enabled the identification of a genetic basis for HS in three patients. We report three novel heterozygous mutations: c.1994 C > A in ANK1, c.5692 C > T, and c.3823delG in SPTB. Sanger sequencing confirmed the presence of these mutations. A further bioinformatic analysis revealed that all identified mutations were classified as pathogenic. To further explore their functional impact, we investigated mRNA expression levels using qRT-PCR. Mature erythrocytes lack mRNA, making them unsuitable for studying gene expression. Therefore, this study employed cultured erythroblasts derived from peripheral blood CD34 + cells to investigate the effect of these novel mutations on gene expression. Total RNA extracted from these cultured erythroblasts was used for cDNA synthesis and subsequent analysis by Sanger sequencing and qRT-PCR. The mRNA sequences corresponding to the three novel mutations were found to be identical to the gDNA sequences.

Spectrin, a major structural protein, forms the underlying cytoskeletal network of the erythrocyte plasma membrane11,32. It associates with band 4.1 and actin to create this essential structure, which maintains the erythrocyte’s characteristic shape and deformability. SPTB consists of an N-terminal actin-binding domain and 17 spectrin repeats containing a dimerization domain, partial spectrin repeats, an ankyrin-binding domain, and a tetramerization domain5. Mutations in SPTB are frequently associated with HS, but the underlying pathogenic mechanisms are not fully understood. This study identified two novel SPTB mutations (c.5692 C > T and c.3823delG). qRT-PCR analysis revealed a significant reduction (> 80%) in SPTB gene expression in cultured erythroblasts derived from CD34 + cells of patients harboring these mutations compared to healthy controls. This finding is consistent with the low peak intensity observed for the mutant allele observed in Sanger sequencing of cDNA. These results suggest that the SPTB mRNA transcript containing these mutations is likely targeted for degradation by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, potentially resulting in β-spectrin deficiency in the erythrocyte membrane. The patient harboring the c.5692 C > T nonsense mutation exhibited a more pronounced clinical presentation (cholelithiasis requiring cholecystectomy) compared to the patient with the c.3823delG frameshift mutation who did not suffer cholelithiasis.

In contrast to the SPTB mutations, the ANK1 c.1994 C > A variant did not show evidence of altered mRNA expression by qRT-PCR, nor did Sanger sequencing of cDNA reveal a lower mutant allele peak. However, SWISS-MODEL analysis (Fig. 5) predicted this variant could generate a truncated ANK1 protein, suggesting a potential functional consequence despite unaltered mRNA expression levels. Ankyrin 1 (ANK1), a critical erythrocyte membrane protein, plays a vital role in stabilizing the RBC structure33. It interacts with spectrin, protein 4.2, and band 3. The identified nonsense mutation in ANK1introduces a PTC within exon 17, predicted to result in a truncated protein lacking the spectrin-binding domain, regulatory domain, and a portion of the membrane-binding domain. The predicted truncation of ANK1 disrupts its interaction with spectrin, a major cytoskeletal protein crucial for erythrocyte membrane stability. Spectrin assembly on the red cell membrane is known to be proportionally reduced when ankyrin-spectrin linkage is abolished. Interestingly, a mouse model harboring truncated ANK lacking the spectrin-binding and C‐terminal regulatory domains recapitulates severe HS34, supporting the functional relevance of this mutation in humans.

Our findings demonstrate elevated levels of red blood cell-derived MPs in HS patients compared to controls, consistent with previous reports9. This suggests that mutations in ANK1 or SPTB, leading to cytoskeletal deficiencies, may create areas of membrane instability, promoting RBC vesiculation and MP release. However, further investigation is needed to elucidate the potential deleterious effects of these MPs, such as activation of the coagulation pathway or thrombosis.

Analysis of erythroblast cultures revealed a significantly higher expansion rate of HS erythroblasts compared to controls. This suggests a potential dysregulation in erythroblast proliferation detected in HS patients. Further studies are needed to validate these findings and clarify the underlying mechanism that may potential link to the observed increased expansion rate of HS erythroid cells.

In conclusion, this study identified novel mutations in the SPTB and ANK1 genes of Thai HS patients. Functional analysis provided evidence supporting the potential pathogenicity of these mutations at the mRNA level. Furthermore, the study demonstrates the utility of cultured erythroblasts derived from peripheral blood CD34 + stem cells as a valuable tool to investigate the mRNA level effects of novel mutations in HS patients.

This study’s limitations of whole-exome sequencing include the inability to detect etiologic mutations in noncoding regions, such as regulatory or deep intronic areas. Additionally, this study’s correlation between phenotypes and gene mutations was heterogeneous. Increasing the sample size could provide further clarity.

Predicted structural models of wild-type and mutant proteins for SPTB (A) and ANK1 (B). The identified ANK1 c.1994 C > A mutation lies within the N-terminal membrane-binding domain. This mutation is predicted to lead to a truncated protein lacking the spectrin-binding and C-terminal regulatory domains, potentially affecting interactions with β-spectrin and other regulatory functions.

Methods

Patient characteristics and laboratory testing

Three patients previously diagnosed with HS and three healthy control subjects were recruited for this study. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine Vajira Hospital, Navamindradhiraj University (COA 134/2565). All subjects provided written informed consent. Inclusion criteria included patients diagnosed with HS based on complete blood count findings and a positive serial dilution osmotic fragility test. Additionally, the included patients and normal subjects were aged between 18 and 60 years old and had not received a blood transfusion in the previous three months before blood donation. The exclusion criteria included HS patients who had co-inheritance of thalassemia, G6PD deficiency, iron deficiency anemia, and other hemolytic anemia, which were confirmed by CBC, hemoglobin typing, iron profile, G6PD enzyme activity, and direct antiglobulin test (DAT).

The results of routinely biochemistry laboratory tests including serum bilirubin, BUN, creatinine and Liver function test were documented. All normal controls were screened to be normal for CBC, hemoglobin typing, iron profile and G6PD enzyme activity.

Flow cytometry analysis of RBC-derived MPs

Red blood cell-derived MP levels were quantified by flow cytometry. Annexin V-staining was used for MPs capture, followed by incubation with anti-Glycophorin A antibodies to specifically detect erythrocyte-derived MPs. Citrate blood samples were collected from three HS patients and three healthy controls. Platelet-free plasma (PFP) was isolated by centrifugation at 2,500 ×g for 15 min. The supernatant (PFP) was then transferred to a new tube and centrifuged again at 2,500 g for 15 min.

For RBC-derived MPs measurement, 5 µL of each PFP sample was incubated with a mixture of 2 µL PE-conjugated anti-CD235 (Glycophorin A) antibody (Thermo Scientific, CA, USA), 3 µL Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated Annexin V (Fluor 488 Annexin V, (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 20 µL of 1 × Annexin V binding buffer at room temperature for 15 min. Following incubation, the stained mixtures were added to preloaded containing fluorescent Trucount™ beads (BD, San Jose, CA, USA) with a known concentration. The samples were then diluted with 300 µl of binding buffer and analyzed using a BD AccuriTM C6 Plus Flow Cytometer (BD, San Jose, CA, USA). All samples were run in duplicate. Events positive for both PE-conjugated anti-CD235 (Glycophorin A) and FITC-conjugated Annexin V were counted as RBC-derived MPs. The absolute number of MPs was calculated using a formula described previously35.

WES andin silico prediction of pathogenicity

Genomic DNA isolated from EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood samples using the PureLink™ Genomic DNA Kit (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) was subjected to WES on a next-generation sequencing Illumina platform (Macrogen, Seoul, Republic of Korea) to screen for mutations in the exons of ANK1, SLC4A1, SPTA1, SPTB, and EPB42 genes. Sequencing library preparation was performed using the SureSelect V7-Post library kit (Illumina). WES data analysis involved a comparison to the reference human genome assembly GRCh38 (hg38) from the UCSC Genome Browser (original GRCh38 from NCBI, Dec. 2013).

Variant calling and filtering were performed using GATK v.44.0.5.1, BWA v.0.7.17, and Picard v.2.18. (SNAPSHOT). SnpEff v.5.0e (2021-03-09) was used for variant annotation against reference genome GRCh38 (hg38 assembly, UCSC Genome Browser) and public databases including dbSNP database (v.138, 154), 1,000 genome project (phase 3), Clinvar (July 2021), Exome Sequencing Project (ESP6500SI_V2) and dbNSFP v.4.2c. In silico prediction of variant pathogenicity was additionally performed using Mutation Taster software. Mutations predicted to result in truncated or structurally abnormal proteins, or those affecting splice sites, were prioritized as potential causative factors for HS.

Validation of mutations by Sanger sequencing

Sanger sequencing was employed to validate potentially pathogenic variants identified by WES. Primers were designed using Primer3plus software (https://primer3plus.com/) and their sequences are provided in Supplementary Table 1. PCR amplification was performed with PCRBIO HS Taq DNA Polymerase (PCR Biosystems, London, UK) on an Eppendorf Mastercycler EP Thermal Cycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). PCR amplification was performed using the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 56°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 20 s. A final extension step at 72°C for 5 min was included. Sanger sequencing, performed by Macrogen service, was used to confirm the identified variants. The sequencing results were compared to reference sequences and those obtained from normal controls.

Isolation of CD34 + hematopoietic stem cells and erythroblast culture

CD34 + hematopoietic stem cells were isolated from peripheral blood following a previously described protocol36. Briefly, 24 mL EDTA-anticoagulant whole blood samples from HS patients and healthy controls were centrifuged at 600 x g for 8 min. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated using Lymphoprep™ (Stem Cell Technologies Inc, Vancouver, BC, Canada) gradient density medium (density 1.077 g/mL). Positive selection with anti-CD34 + magnetic microbeads (MACS™ isolation system; Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA, USA) was then used to enrich for CD34 + cells from the PBMC fraction. To induce erythroid differentiation, isolated CD34 + cells were cultured in a basal medium consisting of Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (GIBCO-Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO-Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 300 ng/mL human holotransferrin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 37 ºC and 5% CO2 for 14 days. The basal medium was further supplemented with 2U/mL erythropoietin (EPO; CILAG GmbH, Zug, Switzerland), 10 ng/mL interleukin-3 (IL-3; Promokine, Heidelberg, Germany) and 50 ng/mL stem cell factor (SCF; GIBCO-Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA ) during days 0–4. Fresh complete medium supplemented with 10 ng/mL SCF and 2 U/mL erythropoietin (EPO; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Beerse, Belgium) replaced the culture medium on days 4 and 8. The expansion rate of cultured erythroblasts from both normal controls and HS subjects was then determined by direct cell counting following Trypan Blue staining during the late differentiation stage (days 8–14).

Analysis of cDNA sequences for the selected SPTB and ANK1 mutations

Total RNA was isolated from day-8 cultured erythroblasts using the TRIzol isolation reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was then performed using the qPCRBIO cDNA Synthesis kit (PCR Biosystems, London, UK). Following the protocol described in the gDNA sequencing section, specific primers for SPTB and ANK1 genes (sequences provided in Supplementary Table 1) were used for PCR amplification.

SPTB and ANK1 gene expression analysis

To quantify the effects of SPTB and ANK1 mutations on gene expression, the mRNA levels of ANK1 and SPTB were measured by reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). Briefly, 1 ul of synthesized cDNA was added to the PCRBIO HS Taq DNA Polymerase master mix (PCR Biosystems, London, UK) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

GAPDH mRNA expression was used for normalization. Primers specific for ANK1, SPTB, and GAPDH (sequences provided in Supplementary Table 2) were used for PCR amplification. The relative quantification of gene expression was performed using the 2−ΔΔCT method. Melting curve analysis after amplification was performed to ensure specific product amplification and minimize the risk of nonspecific products and primer dimers.

In silico prediction of protein pathogenicity

The SWISS-MODEL online server (http://swissmodel.expasy.org) was used to predict and analyze the potential structural changes in SPTB and ANK1 proteins caused by the identified mutations.

Data availability

The raw WES data sets analyzed in the current study are uploaded to The European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA) under accession number PRJEB76254. (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/PRJEB76254).

References

Eber, S. & Lux, S. E. Hereditary spherocytosis–defects in proteins that connect the membrane skeleton to the lipid bilayer. Semin Hematol. 41, 118–141. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminhematol.2004.01.002 (2004).

Risinger, M. & Kalfa, T. A. Red cell membrane disorders: Structure meets function. Blood 136, 1250–1261. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019000946 (2020).

Kalfa, T. A. Diagnosis and clinical management of red cell membrane disorders. Hematology 2021, 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1182/hematology.2021000265 (2021).

Delaunay, J. The molecular basis of hereditary red cell membrane disorders. Blood Rev. 21, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.blre.2006.03.005 (2007).

Iolascon, A., Andolfo, I. & Russo, R. Advances in understanding the pathogenesis of red cell membrane disorders. Br. J. Haematol. 187, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.16126 (2019).

Perrotta, S., Gallagher, P. G. & Mohandas, N. Hereditary spherocytosis. Lancet. 372, 1411–1426. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61588-3 (2008).

Barcellini, W. et al. Hereditary red cell membrane defects: Diagnostic and clinical aspects. Blood Transfus. 9, 274–277. https://doi.org/10.2450/2011.0086-10 (2011).

Mullier, F. et al. Usefulness of microparticles’s release to improve diagnosis of hereditary spherocytosis: Results of a multicentre study. Blood. 116, 2041. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V116.21.2041.2041 (2010).

Basu, S., Banerjee, D., Chandra, S. & Chakrabarti, A. Eryptosis in hereditary spherocytosis and thalassemia: Role of glycoconjugates. Glycoconj. J. 27, 717–722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10719-009-9257-6 (2010).

Leal, J. K. F., Adjobo-Hermans, M. J. W. & Bosman, G. Red blood cell homeostasis: Mechanisms and effects of microvesicle generation in health and disease. Front. Physiol. 9, 703. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00703 (2018).

He, B. J. et al. Molecular genetic mechanisms of hereditary spherocytosis: Current perspectives. Acta Haematol. 139, 60–66. https://doi.org/10.1159/000486229 (2018).

Choi, H. S. et al. Molecular diagnosis of hereditary spherocytosis by multi-gene target sequencing in Korea: Matching with osmotic fragility test and presence of spherocyte. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 14, 114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-019-1070-0 (2019).

Bolton-Maggs, P. H., Langer, J. C., Iolascon, A., Tittensor, P. & King, M. J. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hereditary spherocytosis–2011 update. Br. J. Haematol. 156, 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08921.x (2012).

Park, J. et al. Mutational characteristics of ANK1 and SPTB genes in hereditary spherocytosis. Clin. Genet. 90, 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/cge.12749 (2016).

Glenthoj, A. et al. Facilitating EMA binding test performance using fluorescent beads combined with next-generation sequencing. EJHaem. 2, 716–728. https://doi.org/10.1002/jha2.277 (2021).

Wang, R. et al. Exome sequencing confirms molecular diagnoses in 38 Chinese families with hereditary spherocytosis. Sci. China Life Sci. 61, 947–953. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-017-9232-6 (2018).

Svidnicki, M., Zanetta, G. K., Congrains-Castillo, A., Costa, F. F. & Saad, S. T. O. Targeted next-generation sequencing identified novel mutations associated with hereditary anemias in Brazil. Ann. Hematol. 99, 955–962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-020-03986-8 (2020).

Li, S. et al. A novel SPTB mutation causes hereditary spherocytosis via loss-of-function of beta-spectrin. Ann. Hematol. 101, 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-022-04773-3 (2022).

Peters, L. L. & Lux, S. E. Ankyrins: Structure and function in normal cells and hereditary spherocytes. Semin Hematol. 30, 85–118 (1993).

Iolascon, A. & Avvisati, R. A. Genotype/phenotype correlation in hereditary spherocytosis. Haematologica. 93, 1283–1288. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.13344 (2008).

Bennett, V. & Healy, J. Membrane domains based on ankyrin and spectrin associated with cell-cell interactions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 1, a003012. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a003012 (2009).

Ayhan, A. C. et al. Erythrocyte membrane protein defects in hereditary spherocytosis patients in Turkish population. Hematology. 17, 232–236. https://doi.org/10.1179/1607845412Y.0000000001 (2012).

Agarwal, A. M. Ankyrin mutations in hereditary spherocytosis. Acta Haematol. 141, 63–64. https://doi.org/10.1159/000495339 (2019).

Nakanishi, H., Kanzaki, A., Yawata, A., Yamada, O. & Yawata, Y. Ankyrin gene mutations in Japanese patients with hereditary spherocytosis. Int. J. Hematol. 73, 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02981903 (2001).

Yamamoto, K. S. et al. Clinical and genetic diagnosis of thirteen Japanese patients with hereditary spherocytosis. Hum. Genome Var. 9, 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41439-021-00179-1 (2022).

More, T. A., Devendra, R., Dongerdiye, R., Warang, P. & Kedar, P. Targeted next-generation sequencing identifies novel deleterious variants in ANK1 gene causing severe hereditary spherocytosis in Indian patients: Expanding the molecular and clinical spectrum. Mol. Genet. Genomics 298, 427–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00438-022-01984-1 (2023).

del Miraglia, E. et al. Clinical and molecular evaluation of non-dominant hereditary spherocytosis. Br. J. Haematol. 112, 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02501.x (2001).

Hao, L. et al. Two novel ANK1 loss-of-function mutations in Chinese families with hereditary spherocytosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 23, 4454–4463. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.14343 (2019).

Wu, Y., Liao, L. & Lin, F. The diagnostic protocol for hereditary spherocytosis-2021 update. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 35, e24034. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.24034 (2021).

Kim, Y., Park, J. & Kim, M. Diagnostic approaches for inherited hemolytic anemia in the genetic era. Blood Res. 52, 84–94. https://doi.org/10.5045/br.2017.52.2.84 (2017).

Agarwal, A. M. et al. Clinical utility of next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of hereditary haemolytic anaemias. Br. J. Haematol. 174, 806–814. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14131 (2016).

Mohandas, N. & Gallagher, P. G. Red cell membrane: Past, present, and future. Blood 112, 3939–3948. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2008-07-161166 (2008).

Sun, Q. et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing identified a novel ANK1 mutation associated with hereditary spherocytosis in a Chinese family. Hematology. 24, 583–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078454.2019.1650873 (2019).

Hughes, M. R. et al. A novel ENU-generated truncation mutation lacking the spectrin-binding and C-terminal regulatory domains of Ank1 models severe hemolytic hereditary spherocytosis. Exp. Hematol. 39, 305–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exphem.2010.12.009 (2011). 320.e301302.

Nantakomol, D. et al. The absolute counting of red cell-derived microparticles with red cell bead by flow rate based assay. Cytometry B Clin. Cytom. 76, 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/cyto.b.20465 (2009).

Leecharoenkiat, A. et al. Increased oxidative metabolism is associated with erythroid precursor expansion in β0-thalassaemia/Hb E disease. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 47, 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcmd.2011.06.005 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This Research is funded by Thailand Science research and Innovation Fund Chulalongkorn University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.P. collected samples, performed experiments, analyzed data, organized the figures and drafted the manuscript. C.N. performed experiments. I.N. participated in designing the research study, interpreted the data and editing of this manuscript. K.L. designed the research study, performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, writing and editing of this manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Panarach, C., Netsawang, C., Nuchprayoon, I. et al. Identification and functional analysis of novel SPTB and ANK1 mutations in hereditary spherocytosis patients. Sci Rep 14, 27362 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78622-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78622-w