Abstract

Annual outbreaks of Lassa fever have resulted in a public health threat in Nigeria and other endemic countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. While the Lassa Virus (LASV) is endemic in rodent populations, zoonotic spillover to humans causes annual outbreaks. This study reviewed the burden of Lassa fever (LF) in Nigeria between 2020 and 2023 and conducted a cross-sectional survey of Nigerians to evaluate their risk perceptions of LF. During the period under review, 28,780 suspected and 4,036 confirmed cases of LF were reported from 34 of the 37 states of Nigeria. These cases resulted in 762 deaths (a CFR of 18.9%). The overall case positivity rate was 14% (4,036/28,780), with more positive cases in 2020 (17.5%, n = 1,189/6,791). A total of 2,150 study participants were enrolled in the prospective cross-sectional study, with most of them (87.5%, n = 1,881/2,150) having previously heard of Lassa fever (LF). The numerical scoring system revealed that 35.43% (n = 762/1,881) of those aware of LF have poor knowledge of its preventive measures, route of transmission, and control measures. Approximately 6.84% (n = 147/2,150) of them were at a high risk of contracting LF, with 27.6% (n = 584/2,150) of study participants feeling concerned about contracting LF because of the presence of rodents in their immediate vicinity, occupational exposure to healthcare workers, and the probability of contamination of food by infected rodents without necessary food safety measures. Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that tertiary education was associated with an increased likelihood of better LF knowledge (OR: 17.32; 95% CI: 10.62, 28.26; p < 0.01) and a lower risk of contracting LF when compared to respondents with no formal education. In addition, study participants who reside in low-burden states have lower LF perception than those residents in high-LF-burden states (OR: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.38–0.91; p = 0.049). On the other hand, study participants with poor risk perception (knowledge) of LF had a higher likelihood (RR: 0.33; 95% CI: 0.20, 0.53; p < 0.01) of contracting LF when compared to those with good knowledge of LF. Similarly, those residents in low LF burden states were less likely (OR: 0.09; 95% CI: 0.05,0.17; p < 0.01) to contract LF when compared to those residents in high burden states. There is a need to improve LF diagnostics capacity, infection prevention and control measures, and implementation of the One Health approach to controlling LASV from animal reservoirs. In addition, public enlightenment campaigns to address fundamental knowledge gaps are crucial to mitigating the ongoing and future impact of LF in Nigeria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lassa fever (LF), a disease endemic to West Africa but with the potential to spread further, presents a serious threat to global health. This is due to its status as the most commonly exported viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF) compared to others like Ebola1,2. It is a severe viral infection caused by a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the family Arenaviridae which has a zoonotic origin3,4.

The animal reservoir of the Lassa Fever Virus (LASV) is the multimammate mouse (Mastomys natalensis), a rodent species that is widespread in these endemic countries5,6. Recently, non-rodent hosts such as birds, lizards, and domestic mammals (dogs, pigs, cattle, and goats) were shown to carry the LASV with the lizards having the highest positivity rate by PCR7. The study also reported that seropositivity was highest among cattle and lowest in pigs, although it is unclear the specific impact these additional hosts may have on pathogen diversity, evolution, and transmission7.

The predisposing factors have been reported to include contact with surfaces or food contaminated with rodent urine or feces often during the post-harvest drying of grains in the open or handling of infected rats for consumption8,9. The annual LF epidemic in Nigeria is usually through exposure to virus-infected fluids or excreta from rodents while close contact with infected individuals’ body fluids is usually responsible for human-to-human transmission8,10.

Clinically, most LF cases are asymptomatic, mild, or severe. The severe form of LF could affect multiple organs and tissues and present as facial swelling (edema), bleeding, severe anemia, low blood pressure, confusion, kidney failure, and even coma with death occurring within 14–20 days of experiencing symptoms11,12,13.

In West Africa, Nigeria has the highest burden of LF with the disease outbreak exhibiting a seasonal trend, occurring frequently and reaching its peak during the dry season (November - April)8,14. Over the last 4 years, Nigeria has already recorded Lassa fever outbreaks in 34 of the 37 states including the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) with over 4,036 confirmed cases15. In Nigeria, LF has assumed an endemic and public health emergency status with the case fatality rate getting as high as 71.4% in some states (Table S1). Epidemiologically, LF may be shifting its prevalence from rural areas to major urban centers and sub-urban slums16,17.

Generally, it is believed that improving public awareness of an infectious disease is more likely to increase adherence to preventive practices, improve recognition of symptoms, and improve health-seeking behaviours that could result in early diagnosis, leading to prompt and effective treatment, ultimately helping to combat the disease spread and reduce associated mortality. Empowering communities with information on Lassa fever and its preventive measures is believed to be a key factor in reducing infection rates and the spread of the Lassa fever virus18,19. Therefore, this study reviewed the epidemiology of LF over four years (2020–2023) and assessed the risk perception and risk of contracting LF by conducting a cross-sectional survey of Nigerians.

Methods

Ethical clearance

The ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the Kwara State Ministry of Health, Ilorin, Nigeria with reference number: MOH/KS/24/017. Before the commencement of data collection, the participants were informed about the study objectives and given an overview of the survey instrument. Subsequently, a written and signed informed consent was obtained from each participant by ticking the consent box in the e-questionnaire. The study was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. No further questions were posed to participants that did not consent. No personal identifying information was obtained from the participants, participation in this survey was voluntary, without prejudice, and participants could withdraw at any point.

Study participants and survey methodology

This study presented the findings from a multi-state study that was conducted as a cross-sectional online survey of the populace between the 1st of April and the 5th of May 2024. The inclusion criteria were study participants that were consenting adults (18 years and above), of either gender, all educational background, or social status. All non-consenting and under-aged respondents were not included in the study. The study was designed to collect data from one-third (n = 12) of all states in Nigeria (n = 36) but due to the lack of sufficient data from the Northwest, that region was excluded (Fig. 1). Based on previous prevalence reports16, we calculated at least 100 respondents were required from each of the regions with a minimum of 50 respondents per state. Hence, states with less than 50 respondents were not included in the analysis. Luckily, we recruited some 2,150 study participants from 13 states due to the vast personal connections of some of the collaborators. The study area was targeted to include both high-burden and low-burden states, from each of the five regions. The questionnaire was designed and administered using Microsoft Forms and distributed via online social media platforms.

Questionnaire design

This study evaluated two main self-reported variables among the respondents. These were: the risk perception of LF and the risk of contracting LF. The awareness, perception, and risk of contracting LF was assessed using a semi-structured pre-validated questionnaire. Before its deployment, the survey instrument was initially validated by three independent academic examiners to ascertain the content and face validity of the adapted questionnaire as well as observe for any technical glitches. In addition, the reliability of the survey instrument was assessed using the Cronbach Alpha test (with a score of 0.7) based on 10 purposefully selected questions (5 for risk perception and another 5 for risk of contracting LF). Finally, the questionnaire was pre-tested among 20 individuals from the study states before the deployment of the final version for data collection. The results of the pre-test were not included in the final analysis. The form can be accessed here: https://forms.office.com/e/7yXL8cRqGR.

Data sources and analysis

We obtained data on LF burden from the NCDC disease situation reports. We extracted open-access data for 2020–2023 (4-year period) and were interested in the following parameters: suspected cases, confirmed cases, deaths, and the case fatality rate (CFR). Both the epidemiological data and those obtained from the survey were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). We conducted descriptive statistics and summarized the variables as frequency and percentages. For the primary data obtained from the respondents, we graded each respondent’s selected responses to enable categorization of responses to identify those with good perceptions against others. The risk perception was based on 5 questions (awareness of LF, knowledge of its transmission, symptoms, what increases risk, and prevention). With a cut-off of 60%, respondents with at least three correct scores were graded to have a good perception of LF. Similarly, the risk of contracting LF was also based on five questions (recent travel to high-burden states, recent travel to LF endemic countries, presence of rodents in households, contact with rodents, and availability of good sanitation facilities). We used a cut-off of 80% to determine the proportion of respondents who were at high risk of contracting LF.

Chi-square analysis was used to test for association between the sociodemographic variables and the two outcome variables independently. Finally, the significant variables at p-value < 0.05 were entered into a logistic regression model (univariable and multivariable) to determine the association between the socio-demographic variables (age, gender, level of education, state of residence, religion, tribe, and LF burden) and the outcome variables (LF risk perception and Risk of contracting LF). The odds ratios generated from the multivariable logistic regression analysis were used for all the inferences in this study.

Results

Epidemiology of LF, 2020–2023

During the four years under review, a total of 28,780 suspected cases of LF were reported from all 37 states of Nigeria with at least 1 confirmed case in all states except Akwa Ibom, Yobe, and Kwara State which are yet to have the index case of LF (Fig. 2). Positive laboratory confirmation of LF was done for 4,036 cases which resulted in the death of 762 persons resulting in a CFR of 18.9%. The overall case positivity rate was 14% (4,036/28,780) with more positive cases in early 2020 (before national COVID-19 cases) of 17.5% (1189/6,791). Less LF cases were reported in 2021 (n = 510/4,633) when compared to 2022 (13.0%, n = 1,067/8,201) and 2023 (13.9%, n = 1,270/9,155) when the pandemic was declared over. More cases were reported in high burden states of Edo (1,219 cases; CFR-11%), and Ondo (1,379 cases; CFR-17%). Other high-burden states include Bauchi (432 cases; CFR- 21.3%), Taraba (219 cases; CFR – 37%), and Ebonyi state (202 cases; CFR-41.1%). During the four-year period, the CFR ranged from 0% (Jigawa, Niger, and Osun state) to 71.4% (Cross River State) with an overall national CFR of 18.9% (Table S1).

Demographics of study participants

A total of 2,382 responses were received. Of this, 2,347 respondents consented to participate in the study (response rate is 98.6%). Of those consenting, 2,150 responses were included in this study which represented at least 50 responses from 13 different states. The states represented those with a high burden of LF (Ondo, Benue, Ebonyi, Bauchi, and Taraba) and those with a low burden (Abia, Adamawa, Akwa Ibom, Kwara, Nasarawa, Osun, Kogi, and Imo). The respondents included all age groups, both genders, the two main religions, and the three most common tribes were all represented (Table 1). In terms of geopolitical distribution, five of the six geopolitical regions were well represented in the survey. As with most online surveys, most of the study participants had tertiary education (68.37%, n = 1470/2150).

Awareness and perception of lassa fever among study participants

As an endemic disease with high CFR, most of the study participants (87.5%, n = 1881/2150) have previously heard of Lassa fever. Most of the study participants heard about Lassa fever from multiple sources such as healthcare workers, radio/TV, as well as from social media networks. More than half of the study participants (57.04%, n = 1073/1881) knew that contact with rodents was one of the most common routes of transmission of Lassa. Similarly, participants knew that Lassa could also be transmitted through food/household items that were contaminated with rodent urine/faeces (50.07%, n = 902/1881) and through contact with bodily fluids of infected persons (31.79%, n = 597/1881).

Study participants also knew that Lassa fever could present with symptoms such as fever and fatigue (55.76%, n = 104/1881), gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhoea, and abdominal pain (44.71%, n = 841/1881), headache (36.74%, n = 691/1881) and muscle ache (45.77%, n = 861/1881) (Table 2.). Some of the study participants also knew that the risk of contracting Lassa fever increases when they store food to be consumed in rodent-infested areas (54.01%, n = 1016/1881), did not practice hand hygiene after handling rodents and other rodent-contaminated items (63.79%, n = 1200/1881). Furthermore, they also knew that poor environmental sanitation (15.31%, n = 288/1881) and travelling to high-burden Lassa fever areas (12.38%, n = 233/1881) could increase the risk of contracting Lassa fever. Of the preventive measures, our study participants knew that rodent control, good sanitation practices, and hand hygiene are key to controlling and preventing the spread of Lassa fever. (Table 3.).

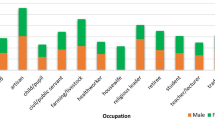

Risk factors for contracting lassa fever

Analysis of our data revealed that 46.75% (n = 1005/2150) of the respondents live or recently traveled to an LF high-burden state. Some 296 persons (n = 13.84%) have also recently travelled to other West African countries that have endemic LF cases. Because rodents are commonplace in most settlements across the country, approximately 69% (n = 1481/2150) of the study participants have rodents in their immediate vicinity and employed several approaches to rodent control (Table 3.). About a quarter of our study participants (n = 565) had contact with rodents either for disposal, consumption, or other purposes, and another quarter of them (n = 550/2150) live in an environment that has poor sanitation, is rural, or has waste disposal challenges, probably increasing the risk of rodent proliferation. While 33% (n = 708/2150) of the study participants were not concerned about contracting LF, 584 of them (27.55%) felt concerned and reported they were at high risk of contracting LF because of the presence of rodents in their immediate vicinity, occupational exposure for healthcare workers, and the probability of contamination of food by infected rodents without necessary food safety measures.

Within the last year, approximately 60% (n = 1113/1881) of the respondents have heard a public enlightenment campaign targeted at increasing awareness on preventive measures of Lassa fever. Most of the participants reported that implementation of Lassa fever preventive measures was very easy. For example, 70% of the respondents found it easy to practice hand hygiene while 23% found it averagely difficult and 7% found it very difficult to practice hand hygiene. Also, while 59.2% found it easy to properly dispose off refuse in closed bins to deter rodents from entering their vicinity, 30.1% found it averagely difficult, and 10.7% found it very difficult to access closed bins and other standard waste disposal facilities near their household (Fig. 3).

The biggest challenges to the attainment of Lassa fever preventive measures as reported by the participants included: lack of access to clean water (25.4%, n = 478/1881), lack of waste disposal and collection facility (15.2%, n = 286/1881), and presence of rodents in the household which is difficult to control (12.2%, n = 230/1881) (Fig. 4).

Predictors of Lassa Fever risk perception and risk of contracting Lassa Fever

Based on a 60% perception cut-off, one-third of our study participants (35.43%, n = 762) were categorized as having poor knowledge and perception of LF. Using a slightly higher cut-off of 80% risk, we believe that 6.84% (n = 147) of our study participants stand a high risk of contracting LF whereas 93.16% (n = 2003/2150) have a low or negligible risk of contracting the disease. The analysis revealed that tertiary education was associated with an increased likelihood of having a better knowledge of LF when compared to respondents with no formal education (OR: 17.32; 95% CI: 10.62,28.26; p < 0.01). Similarly, there was a significant likelihood that study participants who reside in states with low LF burden would have lower LF perception than those resident in high LF burden states (OR: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.38;0.91; p = 0.049). Finally, study participants resident in Ebonyi state (OR: 3.28; 95% CI: 1.82,5.92, p < 0.01) and Kogi state (OR: 2.50; 95% CI: 1.00,6.25; p < 0.01) were more likely to have better LF perception than others (Table 4).

On the other hand, Chi-square revealed that the level of education and state of residence was significantly associated with the risk of contracting LF. Two other variables (risk perception and residence in high or low LF burden states) were significantly associated with a higher risk of contracting Lassa fever. Our data revealed that study participants with poor (sub-optimal) risk perception (knowledge) of LF had a higher likelihood (RR: 0.33; 95% CI: 0.20, 0.53; p < 0.01) of contracting LF when compared to those with good knowledge of LF. Similarly, those residents in low LF burden states were less likely (RR: 0.09; 95% CI: 0.05,0.17; p < 0.01) to contract LF when compared to those residents in high burden states (Table 5).

Discussion

Lassa fever continues to be an important public health problem causing annual epidemics and sporadic outbreaks across various regions of Nigeria. The high burden and CFR of LF have a profound impact on Nigeria’s healthcare system and public health infrastructure. With 28,780 suspected cases, 4,036 confirmed cases, and 762 deaths, LF has highlighted the need for epidemic preparedness, investment in diagnostics, and regional disparities in the quality of healthcare delivery. While there were approximately 6,800 cases in 2020, the reported LF burden dropped in 2021 and peaked in 2022 and 2023. These differences in burden between 2020 and 2023 could be attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic and the impact it had on the reportage and diagnostics of other high-priority infectious diseases such as LF20. In addition, these differences could be attributed to improved disease surveillance and disease reporting systems in Nigeria. Despite these, factors such as the impact of poor sanitation, insufficient healthcare infrastructure, limited access to diagnostics, inadequate infection prevention and control practices, and low levels of awareness among the general population could have influenced the LF burden among states9,21. The differences in the sub-national burden of LF could also be attributed to substantial rural populations in some states that engage in activities like farming and hunting making states such as Ondo, Edo, Taraba, and Bauchi face an elevated risk of LF due to continuous exposure to LASV9.

The data further suggested a higher CFR of 20.5% during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020 and 2021) as against the post-pandemic years of 17.7% (2022 and 2023) (Table S1). The varying prevalence between the high-burden states like Edo, Ondo, and Ebonyi, with CFRs reaching up to 41.1%, necessitates improvements in case management, provision of more diagnostic facilities, upgrading medical infrastructures, and funding active disease surveillance activities to curb the spread of the LASV. The varied CFR across states, from 0 to 71.4%, calls for urgent targeted training for clinicians especially those working in low-burden states such as Cross River, Imo, Bayelsa, and Kaduna as these states have higher CFR. Finally, mass advocacy on LF risk factors, food safety, environmental sanitation, and predisposing socio-cultural practices could help reduce the burden of LF in Nigeria. These awareness campaigns in conjunction with the provision of early diagnostic facilities, training on infection Prevention and control measures among health workers, and annual pre-outbreak preparedness plans could reduce LF burden and prevent these outbreaks8.

The findings of the multi-state survey highlighted key factors associated with the awareness, perception, and risk of contracting Lassa fever in the 13 states of Nigeria. Our study revealed that 87.5% of participants were aware of LF, given there have been frequent outbreaks of Lassa fever and recent awareness campaigns by government and non-governmental organizations in the states across Nigeria16,22,23. Most of the respondents primarily got information from healthcare workers, radio/TV broadcasts, and social media networks. This is similar to a study that reported that most respondents got information about LF through the mass media over time24.

Despite the high awareness rate, one-third of the participants had poor knowledge and perception of LF. This was similar to the knowledge level among 2167 residents of the lower Bambara chiefdom of Sierra Leone25but lower than the knowledge level reported among 858 residents of endemic and non-endemic regions of Liberia26. Most participants understood that transmission commonly occurs through contact with rodents and contaminated items, as well as through the bodily fluids of infected persons24. However, the Lassa fever virus has been found in non-rodent hosts, such as goats, cattle, and lizards, although their roles in the potential transmission and maintenance of the virus have not been fully elucidated7. This calls for more education/awareness on the risks of contracting LF and emphasizes the need for hand hygiene after contact with rodents and wildlife. This further highlights the need for the one health approach in the control and prevention of zoonoses. The One Health approach could help examine the molecular epidemiology in domestic animals, characterize the burden and pathogenicity in domestic animals, and evaluate the risk of direct zoonotic transmission to humans. In addition, the One Health approach could help establish critical control points that could help limit the spread from animal reservoirs to humans8.

The majority of the participants identified the most common presenting symptoms of LF and were aware that storing food in rodent-infested areas and poor hand hygiene increased the risk of contracting Lassa fever. This is in agreement with the report of Dalhat et al8., and Cadmus et al9.,.

While the majority of the study participants correctly identified the most important LF preventive measures, the poor awareness and misconceptions among others could contribute to its continued spread as these individuals lacking proper knowledge about transmission routes, symptoms, and preventive measures might unknowingly engage in high-risk behaviours. This, in turn, could fuel outbreaks and increase the number of infected individuals.

The positive predictors of good knowledge of LF among the study participants were tertiary education and residence in higher-burden states. Studies from Liberia and Sierra Leone had earlier reported higher educational background to be significantly associated with good knowledge of LF25,26. Hence, mass advocacy campaigns should be intensified among the general populace and translated into the local languages to ease the understanding of those without tertiary education. In the same vein, more public enlightenment campaigns are needed in low-burden states to ensure the citizenry is provided with the requisite knowledge to ensure they desist from LF-predisposing risk factors. Across identified hotspots in the country, emphasis should be placed on risk reduction while being involved in predisposing factors such as game animal hunting, which is responsible for sporadic outbreaks in some high-burden states such as Ondo and Taraba state9.

Participants from Bauchi, Ebonyi, Ondo, and Taraba reported practices that increased the likelihood of contracting LF when compared to other states. The risk ratio significantly increases when participants come in regular contact with rodents, either lived in or recently traveled to high-burden states, and visited other West African countries where the disease is endemic. This aligns with the findings of Mari Saez et al27., who reported that Lassa Fever is endemic in West African countries, including Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, southern Mali, northern Côte d’Ivoire, and Nigeria. Around 70% of participants had rodents in their immediate vicinity, and a quarter had direct contact with them. Additionally, a quarter lived in areas with poor sanitation, potentially facilitating rodent proliferation. The NCDC report recommends eliminating rodents in homes and communities through methods such as setting rat traps and maintaining good personal hygiene, like frequent hand washing with soap and water or using hand sanitizers28. In terms of the perceived risk of contracting LF, a third of the participants were not concerned about contracting LF while others expressed concern due to factors such as occupational exposure among healthcare workers, hunting, the risk of food contamination with rodent droppings, and living in a high-burden state29. Across the 13 states, participants reported that the biggest hindrance to practicing preventive measures included a lack of potable water, inadequate waste disposal facilities, and difficulties in controlling rodent populations. Hence, LF preparedness plans using the OH approach, especially at the sub-national level should prioritize waste disposal8,9,29,30,31,32,33.

Multivariate analysis revealed that three main factors (tertiary education, LF risk perception, and residence in a high-burden state) were associated with increased risk of contracting LF. This finding is similar to a study in Ebonyi state that reported very high proportions of the respondents had a high perception of the severity of LF infection, a high perception of susceptibility to LF infection if they don’t carry out preventive practices, and a high perception of self-efficacy towards Lassa fever preventive practices16. The study further reported that those with poor knowledge (low perception) of LF were more likely to contract LF. The importance of public enlightenment campaigns in controlling LF cannot be over-emphasized as our findings showed that participants with tertiary education were more likely to have good knowledge of LF, have higher risk perception, and lower risk of contracting LF. In addition, public education should be directed at states with lower risk perception such as Kwara and Nasarawa.

Clinical diagnosis and laboratory confirmation remain crucial to effective case management and control of LF in endemic regions of West African countries34. To reduce the burden of LF in Nigeria, it is essential to invest in diagnostic capabilities including point-of-care diagnostics. Hence, improving the availability of diagnostic facilities, controlling exposure to the LASV, and LF vaccines are key public health tools that could help control epidemics of LF and reduce the mortality associated with the disease. While there have been several candidate vaccines in clinical trials, no vaccine has currently been approved for LF35,36,37. A scoping review of LF vaccine candidates revealed that four LF vaccine candidates (INO-4500, MV-LASV, rVSV∆G-LASV-GPC, and EBS-LASV) have entered the clinical stage of assessment38. The study further reported that five phase 1 trials and one phase 2 trial evaluating one of these four vaccine candidates have been registered to date. Recently, Kabore et al38., reported that infectious disease experts strongly favored the use of a mass, proactive campaign strategy to immunize a wide age range of people in high-risk areas, including pregnant women and healthcare workers when the vaccine becomes available38. The study further estimated an initial demand of 1 to 100 million doses of LF vaccine, with most demand coming from Nigeria.

This work has certain limitations. Firstly, the use of secondary data may have limited the scope of interpretation of the results and the analyzed dataset may have missed many cases. Secondly, the online cross-sectional survey always limits respondents to people with internet access, limiting the interpretation of the research findings. In addition, we could not get responses from the Northwest due to the shortcomings of the snow-balling approach. Finally, the small sample size in some states might mean that the research findings might not be representative of the whole state. Despite these limitations, this study provides vital information on the epidemiology of LF between 2020 and 2023 and identifies risk factors associated with increased risk of contracting LF across 13 states.

Conclusion

Lassa fever remains a critical public health issue in Nigeria, demanding urgent and sustained attention. The significant disparities in case fatality rates across different states highlight the need for tailored public health interventions and improved healthcare infrastructure. Enhanced awareness campaigns and education about transmission, symptoms, and prevention are essential to reduce the disease spread. Addressing environmental issues, especially rodents, and other pest control and sanitation, will also play a crucial role in mitigating outbreaks. Comprehensive strategies combining medical, educational, and environmental approaches are vital for effectively controlling Lassa fever and reducing its impact on affected communities.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Lehmann, C. et al. Control measures following a case of imported lassa fever from Togo, North Rhine Westphalia, Germany, 2016. Eurosurveillance. 22 (39), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.39.17-00088 (2017).

Choi, M. J. et al. A case of lassa fever diagnosed at a community hospital-Minnesota 2014. Open. Forum Infect. Dis. 5 (7), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofy131 (2018).

Grace, J. U. A., Egoh, I. J. & Udensi, N. Epidemiological trends of Lassa fever in Nigeria from 2015–2021: a review. Therapeutic Adv. Infect. Disease. 8 (X), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/20499361211058252 (2021).

Happi, A. N. et al. Increased prevalence of Lassa Fever Virus-positive rodents and diversity of infected species found during human lassa fever epidemics in Nigeria. Microbiol. Spectr. 10 (4). https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.00366-22 (2022).

Smither, A. R. & Bell-Kareem, A. R. Ecology of Lassa Virus. In: (ed Garry, R.) Lassa Fever: Epidemiology, Immunology, Diagnostics, and Therapeutics. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology, vol 440. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/82_2020_231 (2020).

Wozniak, D. M. et al. Inoculation route-dependent Lassa virus dissemination and shedding dynamics in the natural reservoir–Mastomys natalensis. Emerg. Microbes Infections. 10 (1), 2313–2325. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2021.2008773 (2021).

Happi, A. N. et al. Lassa virus in novel hosts: insights into the epidemiology of Lassa virus infections in southern Nigeria. Emerg. Microbes Infections. 13 (1), 2294859 (2024).

Dalhat, M. M. et al. Epidemiological trends of Lassa fever in Nigeria, 2018–2021. PLoS ONE. 17 (12 December), 2018–2021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279467 (2022).

Cadmus, S. et al. Ecological correlates and predictors of Lassa fever incidence in Ondo State, Nigeria 2017–2021: an emerging urban trend. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47820-3 (2023).

Ilori, E. A. et al. Increase in lassa fever cases in Nigeria, January–March 2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 25 (5), 1026–1027. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2505.181247 (2019).

Dolopei, D. et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) regarding Lassa fever disease among adults in endemic and non-endemic counties of Liberia, 2018: a cross-sectional study. J. Interventional Epidemiol. Public. Health. 4 (2). https://doi.org/10.37432/jieph.supp.2021.4.2.01.9 (2021).

Ojo, M. M. & Goufo, E. F. D. Modeling, analyzing and simulating the dynamics of Lassa fever in Nigeria. J. Egypt. Math. Soc. 30 (1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42787-022-00138-x (2022).

Garry, R. F. Lassa fever — the road ahead. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21 (2), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-022-00789-8 (2023).

McKendrick, J. Q., Tennant, W. S. D. & Tildesley, M. J. Modelling seasonality of Lassa fever incidences and vector dynamics in Nigeria. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 17 (11 November), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0011543 (2023).

NCDC. Lassa Fever Situation Report. (2024). https://ncdc.gov.ng/themes/common/files/sitreps/791c808243b0838371d6917f12c5d565.pdf. Accessed 13 July 2024.

Usuwa, I. S. et al. Knowledge and risk perception towards Lassa fever infection among residents of affected communities in Ebonyi State, Nigeria: implications for risk communication. BMC Public. Health. 20 (1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8299-3 (2020).

Gomerep, S. et al. Epidemiological review of confirmed Lassa fever cases during 2016–2018, in Plateau State, North Central Nigeria. PLOS Global Public. Health. 2 (6), e0000290. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000290 (2022).

Areji, S. C. et al. Knowledge, attitude and Prevention of Lassa fever transmission among women in Nnewi North Lga, Anambra State, Nigeria. Int. J. Trop. Disease Health. 44 (11), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.9734/ijtdh/2023/v44i111439 (2023).

Aloke, C. et al. Combating Lassa fever in west African sub-region: Progress, challenges, and future perspectives. Viruses. 15 (1), 146 (2023).

Uwishema, O. et al. Lassa fever amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: a rising concern, efforts, challenges, and future recommendations. J. Med. Virol. 93 (12), 6433–6436 (2021).

Balogun, O. O., Akande, O. W. & Hamer, D. H. Lassa fever: an evolving emergency in West Africa. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 104 (2), 466 (2021).

Ighedosa, S. U. et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of Lassa fever prevention by students of the University of Benin. J. Sci. Pract. Pharm. 3, 75–83 (2016).

Ossai, E. N. et al. Knowledge and preventive practices against Lassa fever among heads of households in Abakaliki metropolis, Southeast Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. Proceedings of singapore healthcare. ;29(2):73–80. (2020).

Aromolaran, O., Samson, T. K. & Falodun, O. I. Knowledge and practices associated with Lassa fever in rural Nigeria: implications for prevention and control. J. Public. Health Afr. 14 (9). https://doi.org/10.4081/jphia.2023.2001 (2023).

Kamara, A. B. et al. Analysing the association between perceived knowledge, and attitudes on Lassa Fever infections and mortality risk factors in lower Bambara Chiefdom. BMC Public. Health. 24 (1), 1684 (2024).

Dolopei, D. et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) regarding Lassa fever disease among adults in endemic and non-endemic counties of Liberia, 2018: a cross-sectional study. J. Interventional Epidemiol. Public. Health ;4(9). (2021).

Mari Saez, A. et al. Rodent control to fight Lassa fever: evaluation and lessons learned from a 4-year study in Upper Guinea. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12 (11), e0006829 (2018).

Omojuyigbe, J. O., Sokunbi, T. O. & Ogodo, E. C. Multiple crises: Anthrax outbreak amidst Lassa fever and diphtheria endemicity in Nigeria. J. Med. Surg. Public. Health. 1, 100021 (2023).

Abdullahi, I. N. et al. Need for preventive and control measures for Lassa fever through the One Health strategic approach. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare, 29(3), 190–194. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/2010105820932616

Akhmetzhanov, A. R., Asai, Y. & Nishiura, H. Quantifying the seasonal drivers of transmission for Lassa fever in Nigeria. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 374 (1775). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2018.0268 (2019).

Naeem, A. et al. Re-emergence of Lassa fever in Nigeria: a new challenge for public health authorities. Health Sci. Rep. 6 (10), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.1628 (2023).

Wada, Y. H. et al. Knowledge of Lassa fever, its prevention and control practices and their predictors among healthcare workers during an outbreak in Northern Nigeria: a multi-centre cross-sectional assessment. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 16 (3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010259 (2022).

Yaro, C. A. et al. Infection pattern, case fatality rate and spread of Lassa virus in Nigeria. BMC Infect. Dis. 21 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-05837-x (2021).

Boisen, M. L. et al. Field validation of recombinant antigen immunoassays for diagnosis of Lassa fever. Sci. Rep. 8 (1), 5939 (2018).

Ronk, A. J. et al. A Lassa virus mRNA vaccine confers protection but does not require neutralizing antibody in a guinea pig model of infection. Nat. Commun. 14 (1), 5603 (2023).

Tschismarov, R., Van Damme, P., Germain, C., De Coster, I., Mateo, M., Reynard, S.,… Baize, S. (2023). Immunogenicity, safety, and tolerability of a recombinant measles-vectored Lassa fever vaccine: a randomised, placebo-controlled, first-in-human trial. The Lancet,401(10384), 1267–1276.

Sulis, G., Peebles, A. & Basta, N. E. Lassa fever vaccine candidates: a scoping review of vaccine clinical trials. Tropical Med. Int. Health. 28 (6), 420–431 (2023).

Kaboré, L., Pecenka, C. & Hausdorff, W. P. Lassa fever vaccine use cases and demand: perspectives from select west African experts. Vaccine. 42 (8), 1873–1877 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of Musa Gomina Muhammed, Mustapha Ashiru Muhammad, and Ahmad Muhammad Aliyu for their support during the field data collection screening of the isolates. The Helsinki University Library supported the open access publication of the article.

Funding

This work did not receive any funding. The Helsinki University Library provided open access publication for this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IMA, TGO, NAL, OEN, LO, KMU, LO, MO, SMO, EOA, HJJ, AOA, and NRC were involved in the collection of online responses. AIA, OAO, IMA, and TGO wrote the draft manuscript. AIA, ATA, and EA conducted the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This ethical approval for this study was received from the Kwara State Ministry of Health, Ilorin, Kwara State (Reference No: MOH/KS/24/017).

Consent for publication

Not Applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Mustapha, A.I., Adesiyan, I.M., Orum, T.G. et al. Lassa fever in Nigeria: epidemiology and risk perception. Sci Rep 14, 27669 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78726-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78726-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Lassa fever in West Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of attack rates, case fatality rates and risk factors

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

Trends, public health implications, and emerging concerns of Lassa fever in Ondo state, Nigeria

Discover Public Health (2025)

-

Modelling the effects of climate and human factor on Lassa fever distribution in Ondo State Nigeria

International Journal of Biometeorology (2025)