Abstract

This study aimed to assess the reliability and validity of a novel clinical tool for distributing rehabilitation patients (DRP) for measuring a population of rehabilitation patients based on first-hand data from the field survey in China. A multi-stage sampling scheme was used to select 2512 rehabilitation outpatients from 21 medical institutions in seven cities in China. The evaluation indicators of the DRP tool consisted of five clinical indexes on multiple dysfunctions, self-care ability, vital signs, disease status, and disease course. The evaluation of rehabilitation ways of the DRP tool mainly included outpatient rehabilitation treatment, admission to primary healthcare, admission to secondary hospitals, and admission to tertiary hospitals. The mean age of participants was 54.22 years (SD:17.91), and nearly half (48.68%) were male. The majority (70.15%) were diagnosed with orthopaedic disorders. The Cronbach’s alpha (0.66), the Kendall test (Kendall coefficient = 0.86; P < 0.001), and the Kappa test (Kappa = 0.83; Agreement: 90.48%; P < 0.001) reflected acceptable consistency reliability for the indexes on multiple dysfunctions, self-care ability, vital signs, disease status, and disease course in DRP tool. The modified confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) showed the indexes of multiple dysfunctions (β = 0.31; 95%CI = 0.20–0.43), self-care ability (β = 0.99; 95%CI = 0.65–1.33), disease status (β = 0.11; 95%CI = 0.06–0.16), disease course (β = 0.15; 95%CI = 0.09–0.21), and vital signs (β = 0.15; 95%CI = 0.08–0.21) had significantly factor loadings on the rehabilitation ways. The modified CFA exhibited a satisfactory model fit (RMSEA = 0.03; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.95; SRMR = 0.01; AIC = 8268.51; BIC = 8373.43). This is the first study to develop a DRP tool using a relatively large sample from seven cities in China. The DRP tool had acceptable reliability and validity in measuring the rehabilitation ways of patients. Our findings provide a starting point for developing a practical tool in rehabilitation clinical practices and could provide advice on building more effective strategies and tools for other low-and middle-income countries that struggle with integrated healthcare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Faced with the increase of rehabilitation demands due to shifting demographics and health conditions1,2,3, promoting integrated healthcare delivery systems is a promising approach for allocating healthcare resources efficiently for rehabilitation patients. In high-income countries, such as England, the USA, and Germany, rehabilitation delivery systems form interconnected environments4,5,6,7,8,9. In low-and middle-income countries, despite substantial government investment in integrated healthcare delivery systems, disparities in medical resources for rehabilitation patients persist. Similar to other low-and middle-income countries, China has been dedicated to building integrated healthcare delivery systems since 200910. To date, various official policies have advocated for these systems in primary healthcare, secondary, and tertiary hospitals11,12,13. While substantial efforts have been devoted to advancing integrated health delivery systems in China, progress has been suboptimal14,15.

In the pursuit of integrated healthcare delivery systems in rehabilitation, various studies have created tools for this purpose16,17,18. For example, Chinese experts have focused on distribution guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation16and exercise rehabilitation in patients with chronic coronary syndrome17. The USA experts have developed an exercise therapy referral clinical support tool for patients with osteoporosis at risk for falls18. These previous studies could contribute evidence in developing tools for integrated healthcare delivery systems in rehabilitation. However, previous studies have been constrained to individual ailments and have faced challenges in practical rehabilitation settings, especially in primary healthcare. Although the official department in China has published guidance for the referral of rehabilitation patients, the guidance is limited to being used among inpatients, which ignores the needs of outpatients19. To the best of our knowledge, no published evidence exists of a rehabilitation tool capable of effectively and efficiently guiding doctors in patient distribution across medical facilities. The absence of such a tool impedes the development of integrated healthcare delivery systems in rehabilitation.

Within the integrated healthcare delivery systems in rehabilitation, the rehabilitation doctor plays a key role and should be able to clarify the patients’ rehabilitation service needs20,21,22,23. To achieve an effective and efficient distribution of rehabilitation patients, we developed a novel clinical tool for distributing rehabilitation patients (DRP) that can recognize different types of patients (Fig. 1); the details of developing the DRP tool are provided in Supplementary Materials Appendix 2. The function of DRP is to clarify the “4 W”, specifically, when a rehabilitation doctor serves a patient, he or she needs to clarify the following four questions: (1) Who is a rehabilitated patient? (2) What types of rehabilitation services are available? Outpatient service or inpatient service? (3) When refer the patients to the respective hospitals? (4) Where should the patients be referred? Primary healthcare, secondary hospital, or tertiary hospital? The DRP tool consists of five clinical indexes: the level of dysfunction, self-care ability24,25,26, vital signs, disease status, and disease course. The guideline of the DRP tool was provided in Supplementary Materials Appendix 1. We intended to develop a novel clinical tool for DRP and promote integrated healthcare delivery systems for rehabilitation.

The novel clinical tool for distributing rehabilitation patients in China developed by our research group. * Note: The tool was developed by our research group. Figure 1a was the tool, Fig. 1b was the diagram and logic path of the tool. a The Longshi-scale was an evaluation method of self-care ability among disabled people, which was approved by the National Standards Commission of China in 2018 (GB/T37103-2018). b The patient should be referred if his/her functional status did not change for over one month. c The disease course could be different in different cities. d Multiple dysfunctions indicated patients who had conscious impairments, or in addition to motor impairment, they also had any one or more cognitive impairment, speech impairment, swallowing impairment, or cardio-pulmonary impairment.

The reliability and validity of the DRP tool are the basis for further research. In this study, we aimed to assess the reliability and validity of the DRP tool for measuring a population of rehabilitation patients based on first-hand data from the field survey in China.

Methods

Design

We conducted a multicenter, cross-sectional, population-based study from September 12 to December 20, 2023, in 7 cities from 7 provinces in China. The inclusion criteria of participants were (1) he/she had dysfunctional problems; (2) he/she had visited rehabilitation doctors; (3) he/she was an outpatient; and (4) he/she would complete all evaluation procedures. The exclusion criteria of participants were that he/she had visited rehabilitation doctors to help other family members take medicine.

Sampling

As detailed in Fig. 2, a 4-step multistage method was used to select the study’s sample. First, 7 cities in China were selected as sample cities. Second, we randomly selected 1 primary healthcare, 1 secondary hospital, and 1 tertiary hospital within each sampled city. A total of 21 medical institutions were enrolled from 7 cities. Third, all doctors from each sampled medical institution who served outpatient rehabilitation were invited, and doctors would use the DRP tool to evaluate patients’ distribution. A total of 105 doctors were enrolled from 21 medical institutions. Finally, all rehabilitation patients who visited sampled doctors and met the inclusion criteria were enrolled. A total of 2887 participants were invited. Out of 2887 participants, 143 (4.95%) outpatient participants who did not the rehabilitation needs were deleted. 232 (8.03%) outpatient participants were further deleted since they had normal function (had not the rehabilitation needs actually). Therefore, the final analytical sample included 2512 participants.

Procedure

To collect the data on DRP, three programmers from our research group developed the online version of the DRP tool via the WeChat application (the common application and widely used in health projects in China14,24). We invited the doctors from the rehabilitation departments in the sampled medical institutions to use the DRP tool. All invited doctors were trained to grasp the knowledge of each index and the usage of the DRP tool. Trained doctors would serve the sampled patients first, then use the online DRP tool to collect data via the WeChat application. Doctors continually were invited to fill in the questions from the online DRP tool through face-to-face contact with patients in the clinic room or clinic waiting area. After filling all questions according to the patient’s status, the distribution results of rehabilitation ways (including outpatient rehabilitation treatment, visiting other clinical departments, admission to primary healthcare, admission to secondary hospitals, admission to tertiary hospitals, and admission to nursing homes or long-term care institutions) would be displayed automatically in the DRP tool. During training, doctors were informed that the tool was in the validation phase, and they were only required to complete the assessment and not triage based on the DRP tool results. Thus, we believe the distribution results would not impact or disturb doctors’ clinical judgement and practices. All doctors were invited to use the DRP tool independently after serving patients. Then, 20% of participants from each institution were randomly selected to evaluate the interrater reliability; two doctors from the same institution used the DRP tool to evaluate the same patients.

Measurement

The evaluation indicators of the DRP tool

The indicators of the DRP tool consisted of patients’ basic characteristics on age and sex, and the five clinical indexes on the level of dysfunction, self-care ability, vital signs, disease status, and disease course. The five clinical indexes of the DRP tool were selected based on the literature review, several rounds of expert consultation, and research group discussion. The details of developing the DRP tool and the selection of five clinical indexes are provided in Supplementary Materials Appendix 2. Doctors were invited to evaluate according to these five clinical indexes.

(1) Level of dysfunction: included ‘dysfunction’, ‘multiple dysfunctions’, and ‘without dysfunction’. ‘Dysfunction’ indicates that the patients had any of the following conditions: ①Cognitive impairment: patients had cognitive impairments that affect his/her judgment of people, time, and place; ②Speech disorders: patients had speech impairments that affect his/her communication; ③Dysphagia: patients had swallow impairments that affect his/her oral intake; ④Cardiopulmonary disorders: patients had heart and/or lung function impairments that affect his/her limb mobility; ⑤Movement disorders: patients had motor impairments that affect his/her trunk, upper limb, or lower limb mobility; ⑥Other disorders: patients had experiencing functional impairments other than the five disorders mentioned above. ‘Multiple dysfunctions’ indicated patients who had conscious impairments, or in addition to motor impairment, they also had any one or more cognitive impairment, speech impairment, swallowing impairment, or cardio-pulmonary impairment. If none of the above conditions applied, it was considered ‘without dysfunction’. In our study, we used the variable of multiple dysfunctions in the final analysis, multiple dysfunctions were dummy variables in our study (1 = yes; 0 = no).

(2) Self-care ability: our research group developed a method for assessing self-care ability in daily life using a scenario diagram (the Longshi-scale), which was approved by the National Standards Commission of China in 2016 as an evaluation method of self-care ability concerning Activities of Daily Living among disabled people (20162587-T-314)25,26,27. According to the Longshi-scale, the patient could be divided into three types of groups, ‘community group’, ‘domestic group’, and ‘bedridden group’. ①Community group: referred to the person who can actively move outdoors (including the use of assistive devices and the impact of the environment); ②Domestic group: referred to the person who can take the initiative to get out of bed, cannot take the initiative to move outdoors, and the scope of activity is limited to the family environment (including the use of assistive devices and the impact of the environment); ③Bedridden group: referred to a person who cannot voluntarily get out of bed and whose scope of activity is limited to bed (including the use of assistive devices and environmental influences). Self-care ability was a category variable in our study (1 = community group; 2 = domestic group; 3 = bedridden group).

(3) Vital signs: included patients’ temperature, pulse, heart rate, and respiration. ‘Stable vital signs’ referred to these indicators being within the normal range. ‘Unstable vital signs’ mean that these indicators are beyond the normal range and are possible to threaten patients’ lives. The vital signs were dummy variables in our study (1 = unstable; 0 = stable).

(4) Disease status: encompassed the patient’s basic disease, underlying conditions, complications, and comorbidities. ‘Disease had not been controlled’ refers to any of the following situations: ①Failing to achieve clinical ideal parameters; ②Developing new clinical symptoms; ③Requiring the use of new medications. If none of the above situations happened, it was considered ‘Disease had been controlled’. The disease status was a dummy variable in our study (1 = uncontrolled; 0 = controlled).

(5) Disease course: doctors were asked to fill in the questions about the disease course of patients. According to medical insurance policies, medical insurance does not cover patients’ hospitalization expenses whose course of disease was longer than the duration limitation28,29,30,31,32. The duration limitations were diverse in different sampled cities (the duration limitation was 12 months in Shenzhen, Changzhou, Chengdu, Haikou, and Linyi; the duration limitation was 6 months in Hangzhou; the duration limitation was 3 months in Mile)28,29,30,31,32. The duration limitation from medical insurance policies would impact the doctors’ decision or referred service and the DRP tool’s triage results. So, the actual disease duration was designed into the logical judgement condition in our study. Specifically, if the input of actual disease duration exceeds the limitation of medical insurance, the DRP tool would provide the results of “more than duration limitation”; otherwise, the DRP tool would provide the results of “within duration limitation.” The dummy variable of disease duration (1 = more than duration limitation; 0 = within duration limitation) was used in the analysis.

The evaluation of rehabilitation ways

Rehabilitation ways were regarded as the distribution results of the DRP tool in our study. The evaluation of rehabilitation ways was based on doctors’ clinical experience and the DRP tool. ‘Evaluation of rehabilitation ways based on clinical experience’ in our study indicated that after rehabilitation patients visited sampled doctors, doctors evaluated the distribution of patients (rehabilitation ways) based on their own clinical experience. ‘Evaluation of rehabilitation ways based on DRP tool’ in our study indicated that after rehabilitation patients visited sampled doctors, doctors used the DRP tool in the WeChat application to evaluate the distribution of patients (rehabilitation ways). The rehabilitation ways consisted of outpatient rehabilitation treatment, visiting other clinical departments, inpatient rehabilitation treatment, and admission to nursing homes or long-term care institutions. Regarding inpatient rehabilitation treatment, the results included different levels of medical institutions, that is admission to primary healthcare, admission to secondary hospitals, and admission to tertiary hospitals.

(1) Outpatient rehabilitation treatment: outpatient rehabilitation treatment indicates that the treatment needs of patients could be met in outpatient rehabilitation, other than seeking hospitalization services.

(2) Visiting other clinical departments: if patients visited rehabilitation doctors, but he/she had no rehabilitation needs in fact, these types of patients could be recommended to visit other clinical departments.

(3) Admission to primary healthcare: primary healthcare indicates that primary hospitals and health institutions directly provide prevention, medical treatment, health care and rehabilitation services to the community of a certain population.

(4) Admission to secondary hospitals: secondary hospitals indicated that regional hospitals provide comprehensive medical and health services to multiple communities and undertake certain teaching and scientific research tasks.

(5) Admission to tertiary hospitals: tertiary hospitals indicated that regional and above hospitals provide high-level specialized medical and health services to several regions and perform higher teaching and scientific research tasks.

(6) Admission to nursing homes or long-term care institutions: if the disease course of patients was more than the duration limitation, in this case, the medical insurance did not cover patients’ hospitalization expenses. These types of patients could be recommended to visit nursing homes or long-term care institutions.

In our study, the rehabilitation ways (either the evaluation based on doctors’ clinical experience or based on the DRP tool) were firstly coded as category variables (1 = outpatient rehabilitation treatment; 2 = visiting other clinical departments; 3 = admission to primary healthcare; 4 = admission to secondary hospitals; 5 = admission to tertiary hospitals; 6 = admission to nursing homes or long-term care institutions). Since the DRP tool we developed was mainly focused on the rehabilitation department and public medical institutions, ‘visiting other clinical departments’ and ‘admission to nursing homes or long-term care institutions’ were out of the scope of the DRP tool, the reliability analysis was carried out in four types of rehabilitation ways. In special, when the reliability analysis was carried out in all rehabilitation ways, the category variables of rehabilitation ways (from 1 outpatient rehabilitation treatment to 4 visits to admission to tertiary hospitals) were used in analysis; when the reliability analysis was carried out in different rehabilitation way, the rehabilitation ways of ‘outpatient rehabilitation treatment’, ‘admission to primary healthcare’, ‘admission to secondary hospitals’, and ‘admission to tertiary hospitals’ would be coded as the dummy variables (1 = yes; 0 = no).

Statistical analysis

The empirical strategy included 3 parts. First, descriptive analyses were used to assess the statistical values of the variables that measured the characteristics of the DRP tool. Continuous variables were expressed as mean and SD, and categorical variables as numbers and percentages. Second, to examine the reliability of the DRP tool, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to indicate the internal consistency reliability, where Cronbach’s alpha ≥ 0.70 was considered satisfactory33,34. The Kendall test and Kappa test were carried out to examine the consistency and reliability between two doctors. Third, to examine the validity of the DRP tool, we first conducted the construction validity via exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Bartlett’s test of sphericity was used for testing the possibility of performing factor analysis. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) statistic varied between 0 and 1 in EFA. A value close to 1 indicated relatively compact patterns of correlations. Then, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to verify the identified factor structure and determine the goodness-of-fit of the extracted factor model. CFA was conducted using latent variables (not directly observed but estimated from directly measured variables) and measured variables (directly observed variables). In our study, the latent variable is the rehabilitation ways, the measured variables were five clinical indexes on the multiple dysfunctions, self-care ability, vital signs, disease status, and disease course. The comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) were regarded as testing the fit of the model to the covariance matrix in CFA35,36,37. The CFI and TLI values ranged from 0 to 1, and a value of > 0.90 represented a satisfactory model fit35,36,37. RMSEA and SRMR of < 0.05 were suggested as an indicator of close fit35,36,37. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA Statistical Software Release 14.1 (https://www.stata-press.com). The descriptive analyses were conducted in a total sample of 2512 participants. Since the DRP tool was mainly focused on the patient’s distribution between public medical institutions and in the rehabilitation department. Thus, the reliability and validity of the DRP tool were examined among 2115 participants with the rehabilitation ways on outpatient rehabilitation treatment, admission to primary healthcare, admission to secondary hospitals, and admission to tertiary hospitals.

Ethic approval

Our studies were approved by the Second People’s Hospital of Shenzhen Ethical Review Board (approval number of studies: 2023-226-02PJ). All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were informed of the nature and purpose of the study before providing written consent. All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study. For the children, informed consent for the children’s involvement would be obtained from their caregivers.

Results

Characteristic of evaluation indicators of the DRP tool

The characteristics of the DRP tool indexes are shown in Table 1. A total of 2512 participants were enrolled in the analysis, the mean age of participants was 54.22 years (SD:17.91), and nearly half (48.68%) were male. The majority (70.15%) were diagnosed with orthopaedic disorders. In terms of the five clinical indexes of the DRP tool, the majority (98.00%) of participants had movement disorders, and part of the participants (40.41%) had multiple dysfunctions. Regarding self-care ability, most were evaluated as a community group (69.03%). The disease status of some participants had been controlled (12.15%). Regarding the disease course, some participants (24.01%) reported that their disease course was more than the duration limitation of local medical insurance coverage on hospitalisation expenses. A few participants diagnosed that their vital signs were unstable (0.82%). The median evaluation time was 96.02 s (IOR: 76.01, 140.05).

The evaluation of rehabilitation ways

Regarding the evaluation of rehabilitation ways, as shown in Fig. 3, we first collected the data on the evaluation of rehabilitation ways based on the doctor’s clinical experience. More than one-third were evaluated as ‘outpatient rehabilitation treatment’ (36.01%), few were evaluated as ‘visiting other clinical departments’ (0.71%) and ‘admission to nursing homes or long-term care institutions’ (3.10%), some others were evaluated as ‘admission to primary healthcare’ (17.05%), ‘admission to secondary hospitals’ (21.62%), and ‘admission to tertiary hospitals’ (21.51%), respectively. We secondly collected the data on the evaluation of rehabilitation ways based on the DRP tool. More than half were evaluated as ‘outpatient rehabilitation treatment’ (60.71%), few were evaluated as ‘visiting other clinical departments’ (2.31%) and ‘admission to nursing homes homes or long-term care institutions’ (13.52%), some others were evaluated as ‘admission to primary healthcare’ (8.25%), ‘admission to secondary hospitals’ (11.10%), and ‘admission to tertiary hospitals’ (4.11%), respectively.

Evaluation of rehabilitation ways based on clinical experience and DRP tool (N = 2512). Notes: ‘Evaluation of rehabilitation ways based on clinical experience’ in our study indicated that after rehabilitation patients visited sampled doctors, doctors evaluated the distribution of patients (rehabilitation ways) based on their own clinical experience. ‘Evaluation of rehabilitation ways based on DRP tool’ in our study indicated that after rehabilitation patients visited sampled doctors, doctors used the DRP tool in the WeChat application to evaluate the distribution of patients (rehabilitation ways).

Reliability of the DRP tool

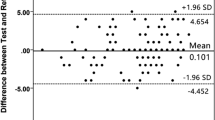

The reliability of the DRP tool was examined among participants with the rehabilitation ways on outpatient rehabilitation treatment, admission to primary healthcare, admission to secondary hospitals, and admission to tertiary hospitals (N = 2115). As shown in Table 2, the reliability of the DRP tool was analyzed. In terms of internal consistency reliability, the overall Cronbach’s alpha was 0.66 for the evaluation results of all rehabilitation ways through five clinical indexes on multiple dysfunctions, self-care ability, vital signs, disease status, and disease course. The Cronbach’s alpha was moderate (α > 0.5) for the evaluation results of ‘outpatient rehabilitation treatment’ and ‘admission to a secondary hospital’. In contrast, the Cronbach’s alpha was lower (α < 0.5) for the evaluation results of ‘admission to primary healthcare’ and ‘admission to tertiary hospitals’. In terms of consistency reliability between two doctors, the results show good consistency for the evaluation results of all rehabilitation ways (Kendall coefficient = 0.86; Kappa = 0.83; Agreement: 90.48%), outpatient rehabilitation treatment (Kendall coefficient = 0.89; Kappa = 0.89; Agreement: 94.76%), admission to primary healthcare (Kendall coefficient = 0.89; Kappa = 0.88; Agreement: 97.62%), admission to secondary hospitals (Kendall coefficient = 0.79; Kappa = 0.79; Agreement: 97.62%), and admission to tertiary hospitals (Kendall coefficient = 0.66; Kappa = 0.66; Agreement: 98.10%).

Construct validity of the DRP tool

The construct validity was examined among participants with the rehabilitation ways on outpatient rehabilitation treatment, admission to primary healthcare, admission to secondary hospitals, and admission to tertiary hospitals (N = 2115). We first summarized results from the KMO and Bartlett test in Appendix Table 1. The results showed that the data were acceptable for factor analysis, the KMO value of each index from the DRP tool was higher than 0.50, and the overall KMO was 0.56 (Bartlett test \(\:{\:}^{2}\)= 549.35; P < 0.001).

We secondly performed a 1-factor CFA model of DRP tool indexes. In the CFA model, the observed variable was five clinical indexes of the DRP tool, the unobserved variable which is a single latent construct was considered as the rehabilitation ways (outpatient rehabilitation treatment, admission to primary healthcare, admission to secondary hospitals, and admission to tertiary hospitals). We first fitted the unmodified model, the results of the unmodified model are shown in Table 3 (columns 2–4) and Fig. 4 (panel A). We then modified the CFA model based on modification indices. In the modified model, we added the paths between multiple dysfunctions and disease course, the path between disease status and disease course, and the path between disease course and vital signs. The results of the modified model are shown in Table 3 (columns 5–7) and Fig. 4 (panel B). The results indicated that the indexes of multiple dysfunctions (β = 0.31; 95%CI = 0.20–0.43), self-care ability (β = 0.99; 95%CI = 0.65–1.33), disease status (β = 0.11; 95%CI = 0.06–0.16), disease course (β = 0.15; 95%CI = 0.09–0.21), and vital signs (β = 0.15; 95%CI = 0.08–0.21) had significantly factor loadings on the rehabilitation ways. The modified CFA model exhibited a satisfactory model fit (RMSEA = 0.03; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.95; SRMR = 0.01; AIC = 8268.51; BIC = 8373.43). We visualized the unmodified and modified models in Fig. 4. All paths in Fig. 4 were significant.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the DRP tool (N = 2115). Notes: The arrow indicated the standardized paths, all paths were significant. The rectangle indicated measured variables (directly observed variables). The oval indicated latent variables (not directly observed but estimated from directly measured variables). ‘Rehabilitation ways’ indicated the DRP tool evaluation results of rehabilitation ways on outpatient rehabilitation treatment, admission to primary healthcare, admission to secondary hospitals, and admission to tertiary hospitals. The circles indicated errors in each measured variable.

Discussion

Promoting integrated healthcare is essential to allocate health service resources and alleviate the medical burden of patients. In the rehabilitation clinical practice, how to distribute rehabilitation patients effectively and efficiently remains an important issue. However, there was no evidence to develop a practical DRP tool for medical doctors in rehabilitation. In this study, we aimed to assess the reliability and validity of the DRP tool, a newly developed tool designed to evaluate the distribution of rehabilitation patients. The reliability analysis evaluated the clinical indexes on multiple dysfunctions, self-care ability, vital signs, disease status, and disease course in the DRP tool. Results showed acceptable internal consistency and good consistency between different evaluators towards the DRP tool. An examination of the construct validity indicated that the DRP tool was moderately related to the rehabilitation ways of patients (outpatient rehabilitation treatment, admission to primary healthcare, admission to secondary hospitals, and admission to tertiary hospitals).

The item internal consistency reliability analysis indicated that internal consistency for all rehabilitation ways and rehabilitation ways on ‘outpatient rehabilitation treatment’ were acceptable38. Although Cronbach’s alpha exceeded the 0.70 level indicating high reliability of scale, some other evidence also indicated that Cronbach’s alpha exceeded the 0.60 indicating acceptable39. Unfortunately, the results of the item internal consistency reliability analysis for the rehabilitation ways on ‘admission to primary health’, ‘admission to secondary hospitals’, and ‘admission to tertiary hospitals’ were relatively low38. The lower item internal consistency reliability is similar to a previous similar study. One study in France developed the infantile hemangioma referral score, a clinical tool for physicians. The results indicated that the internal consistency was 0.5140. The item heterogeneity might be explained the low Cronbach’s alpha values. Regarding the item internal consistency reliability, it is a statistical measure that assesses the consistency of the items within a scale. It is used to evaluate whether the items that are supposed to measure the same construct are indeed related to one another. In our study, the DRP tool is not a traditional scale; the items of the DRP tool were reflected in the real world in the clinic, and patients’ service needs and doctors’ decision-making on triage should be evaluated by the comprehensive and multi-dimension indexes. Therefore, the items in the DRP tool were reflected in different dimensions, including the level of dysfunction, self-care ability, vital signs, disease status, and disease course. For the ‘outpatient rehabilitation treatment,’ it mainly used one item of the level of dysfunction to decide the results. For the ‘admission to primary healthcare,’ ‘admission to secondary hospitals,’ and ‘admission to tertiary hospitals,’ it used all items of the level of dysfunction, self-care ability, vital signs, disease status, and disease course. The item heterogeneity could impact the item internal consistency when evaluating the service needs of hospitalization.

We further invited two doctors to evaluate the same patients using the DRP tool. The consistency reliability analysis showed a high consistency between different doctors. Generally, the enrolled rehabilitation patients in our study were evaluated consistently to the indexes in the DRP tool, which indicated the DRP had acceptable reliability. We found three implications for clinical practice from the results of high consistency. Firstly, high consistency reliability implies that the DRP tool can be standardized across different health practitioners, ensuring that patients receive consistent and reliable evaluations regardless of who administers the tool. Secondly, the high consistency reliability suggests that the DRP tool requires minimal specialized training, making it more accessible to a wider range of healthcare providers. Thirdly, this consistency ensures that the quality of patient care is maintained across different practitioners, which is crucial for maintaining standards in healthcare delivery. Overall, this finding is significant as it suggests that the assessment tool is reliable and can be consistently applied by different healthcare professionals.

Regarding the validity of the DRP tool, to the best of our knowledge, no evidence developed the DRP tool before, and no ‘golden criterion’ for distributing rehabilitation patients can be used to examine the criterion validity of the DRP tool in the study. To examine the validity of the DRP tool, we conducted a factor analysis to verify the construct validity of the DRP tool. The results showed that the KMO value was higher than 0.5 in EFA results, which indicated the indexes of the DRP tool were moderate to conduct factor analysis. Moreover, we conducted CFA and got a CFA model with a satisfactory model fit. Among all indexes of the DRP tool, the index of self-care ability performed the biggest loading on the rehabilitation ways. Self-care ability is a measure that evaluates an individual’s ability to manage their own healthcare needs. Regarding rehabilitation patients, self-care ability can significantly determine the form of rehabilitation services they need. Several reasons could be explained the greatest contribution of self-care ability. Patients with higher self-care ability usually had robust physical and mental support; they may require less intensive care or medical interventions, they were able to manage outpatient or home-based rehabilitation services independently and effectively41,42,43. Conversely, patients with lower self-care ability usually lack robust physical and mental support; they might need more comprehensive and specialized care, which is typically available at higher-level medical institutions with more resources dedicated to patient care, including staff, equipment, and specialized programs42,44,45,46. In general, self-care ability helps healthcare providers make informed decisions about the most appropriate level of medical care and the specific form of rehabilitation services needed47. It ensures that patients receive care that matches their abilities and needs, potentially leading to better outcomes and satisfaction47. Although the indexes of medical conditions, disease course, and vital signs had relatively smaller loading on the rehabilitation ways, these three indexes showed significant contributions to the decision of rehabilitation ways. Overall, the indexes of the DRP tool had acceptable construct validity.

The Chinese government has published guidance for the referral of rehabilitation patients19, specifically addressing stroke patients as one of the most common cases seen in rehabilitation clinical practice. According to this guidance, stroke patients admitted to primary healthcare and secondary hospitals should be referred to tertiary hospitals under certain circumstances: (1) present with intracranial active haemorrhage or progressive cerebral oedema, severe lung infection, urinary tract infection, sepsis, or severe pressure ulcer; (2) the dysfunction is worse; (3) the failure of multiple organs, (4) present the severe mental disorders19. For the stroke patients admitted to the tertiary hospital, he/she would be suggested to be referred to the community or home rehabilitation if present the following scenarios: (1) vital signs become stable, the clinical laboratory examination indexes of stroke were generally normal; (2) disease had been controlled; (3) had mild dysfunction, there is no need for hospitalization rehabilitation19. One study in Pittsburgh developed a triage and referral system to make exercise and rehabilitation referrals standard of care in oncology. The system has questions on difficulty completing daily activities, recent falls, recent cancer treatments, and recent symptoms, about catheters, current exercise, and confidence with exercise48. The rehabilitation and primary care treatment guidelines in South Africa indicated that patients are only able to access rehabilitation by referral from a primary healthcare nurse or medical officer49. A systematic review was conducted to examine referral criteria for palliative care among patients with dementia. The review identified several categories of referral criteria including disease-based referral criteria (dementia stage, medical complications of dementia, prognosis, etc.), needs-based referral criteria (physical symptoms, poor nutrition status, functional decline, etc.), and other referral criteria (enteral feeding/feeding tube, no verbal communication)50. Both the DRP tool and the guidance from previous evidence prioritize patient safety and optimal care. However, our DRP tool provides specific criteria for distributing rehabilitation outpatients, which is currently not addressed by the existing evidence. This includes assessing factors such as self-care ability, severity of disability, and dysfunction level, which are crucial for determining the appropriate level of care and type of service. Distributing rehabilitation outpatients is the first and essential step to deciding the distribution direction of rehabilitation patients. The DRP tool builds upon the existing government guidance by providing a systematic approach to triage rehabilitation outpatients. Using a standardized DRP tool can help reduce variability in referral decisions and improve the efficiency of the referral process. Therefore, developing the DRP tool and verifying its reliability and validity was an innovative and meaningful effort in clinical rehabilitation settings.

Noteworthily, in our study, several invited doctors reported that they had a ‘ruler’ in their mind (such as the results in the bar of “Evaluation of rehabilitation ways based on clinical experience” in Fig. 3). The ‘ruler’ was used to measure the distribution of rehabilitation patients. They also reported that the ‘ruler’ may be different among doctors due to the diversity of backgrounds and clinical experience. We further analyzed the consistency between the evaluation of rehabilitation ways based on ‘clinical experience of doctors” and ‘DRP tool’. Further analysis showed the inconsistency between the two types of evaluation (Appendix Table 2). We believe the supplementary findings strengthened the importance of our research. Our study helps to make the ‘ruler’ (distribution criteria in doctors’ minds) a practical tool. The novel DRP tool we developed matches clinical practice in rehabilitation and meets health reform requirements. Also, the reliability and validity of the DRP tool were proved acceptable in our study. Furthermore, we proved the feasibility of the DRP tool in a clinical setting. On the one hand, findings in our study showed that the average evaluation time was about one and half minutes. The time is less than that of other similar medical assessment tests. The results from the above study in Pittsburgh developed a triage and referral system that showed it took 2–5 min per patient to use the system48. One study conducted in Sweden developed a new pediatric triage system based primarily on vital parameters. They showed it takes 6 minutes to use the tool51. On the other side, the DRP tool was developed and used in WeChat (the common application and widely used in health projects in China14,24), and we achieved the visualization of the DRP tool. This can promote the generalization of DRP tools in clinical settings in the future.

Our study has several limitations. First, this study used cross-sectional measurements. Therefore, the DRP tool was only administered on a single occasion. We were unable to evaluate some of the potentially important psychometric properties such as test-retest reliability or sensitivity to change. Secondly, there was no ‘golden criterion’ about the distribution of rehabilitation patients from previous evidence, so we could not conduct a criterion validity analysis. Thirdly, the fact that a large percentage of the sample comprised orthopaedic disease patients might affect the generalization of our findings. Our findings can only represent the fact of outpatient rehabilitation in sampled cities in China. Additionally, the DRP tool was applied in the public medical institution, “visiting nursing homes or long-term care institutions” was also out of the scope of the DRP tool, so it was not included in the reliability and validity analysis, which may also impact the generalization of the findings. Fourthly, since the trained doctors already know the indexes of the DRP tool, or some doctors recognize the DRP tool results can guide their clinic work. Using the DRP tool may interfere with a doctor’s clinical judgment. To prevent interference, we already emphasized that the DRP tool was in the validation phase and doctors were not required to triage based on the DRP tool. Notwithstanding these limitations, our findings provide support for the utility of the DRP tool, as well as highlight its potential in clinical settings.

Conclusion

Distributing rehabilitation patients effectively and efficiently is meaningful to promoting integrated healthcare in rehabilitation. The use of the DRP tool should be encouraged during this pace. However, no studies have developed a reliable and valid DRP tool to apply in rehabilitation clinic practice. To bridge this research gap, we developed a novel clinical tool for distributing rehabilitation patients and investigated the reliability and validity of the tool. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to develop a DRP tool using a relatively large sample from seven cities in China. We have shown that the DRP tool is reliable, valid, and feasible in rehabilitation departments from different levels of medical institutions in sampled cities in China. More future studies are needed to evaluate the reliability and validity of the DRP tool in clinical settings in China. The findings of this study support the use of the DRP tool for assessing the rehabilitation ways among sampled rehabilitation patients and provide a starting point for developing a practical tool in rehabilitation clinical practices. Furthermore, our findings could provide advice on building more effective strategies and tools for other low-and middle-income countries that struggle with integrated healthcare.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed for the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions related to the consent given by participants at the time of study commencement. An ethically compliant dataset may be made available by the corresponding author on reasonable request and upon approval by the Second People’s Hospital of Shenzhen Ethical Review Board. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to ylwang668@163.com.

References

World Health Organization. Rehabilitation. (2022). https://covid19.who.int/. [Accessed 2023-12-01].

Cieza, A., Causey, K. & Kamenov, K. et sl. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 396, 2006–2017 (2020).

Bickenbach, J., Stucki, G., van Ginneken, E. & Busse, R. Strengthening Rehabilitation in Europe. Health Policy (Amsterdam Netherlands). 126, 151 (2022).

Du, X. et al. Comparing the model of developing medical treatment combination and integrated healthcare system in different countries. Chin. Hosp. 21, 40–42. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-0592.2017.12.014 (2017).

Zhang, X. & Zhuang, Y. Experience in developing integrated healthcare system from western countries. Journal of Translation From Foreign Literatures of Economics. 14–23 (2018).

Asaria, M. et al. How a universal health system reduces inequalities: lessons from England. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 70, 637–643 (2016).

Shevchuk, V. I. et al. Wiad Lek 73, 2040–2043 (2020).

Kwakkel, G. et al. Motor rehabilitation after stroke: European Stroke Organisation (ESO) consensus-based definition and guiding framework. Eur. Stroke J. 8, 880–894. https://doi.org/10.1177/23969873231191304 (2023).

Cao, Y. J., Nie, J. & Noyes, K. Inpatient rehabilitation service utilization and outcomes under US ACA Medicaid expansion. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21, 258. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06256-z (2021).

National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Guidance of further reforming the medical and healthcare system https://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2009-04/06/content_1278721.htm. (2009). [Accessed 2023-12-01].

Ekirapa-Kiracho, E. et al. Maternal and neonatal implementation for equitable systems. A study design paper. Glob Health Action. 10, 1346925. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2017.1346925 (2017).

Government of the People’s Republic of China. Notice on the issuance of opinions on accelerating the development of Rehabilitation Medicine. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2021-06/17/content_5618767.htm(2021). [Accessed 2023-12-01].

Government of the People’s Republic of China. Notice on the Issuance of the Key Tasks for Deepening the Reform of the Medical and Health System in 2024. (2024). https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/202406/content_6955904.htm

Xiao, Y., Husain, L. & Bloom, G. Evaluation and learning in complex, rapidly changing health systems: China’s management of health sector reform. Globalization Health. 14, 112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-018-0429-7 (2018).

Liang, D., Mays, V. M. & Hwang, W. C. Integrated mental health services in China: challenges and planning for the future. Health Policy Plann. 33, 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx137 (2018).

Chinese Hospital Association Cardiac Rehabilitation Management Specialized Committee. Guidance consensus on graded diagnosis and treatment of cardiac rehabilitation in China. Chin. J. Interventional Cardiol. 30, 561–572 (2022).

Branch, C. M. D. A. C. Guidance on graded diagnosis and treatment in exercise rehabilitation of patients with chronic coronary syndrome in China. Chin. J. Interventional Cardiol. 29, 361–370 (2021).

Bullock, G. S. et al. Development of an exercise therapy referral clinical support tool for patients with osteoporosis at risk for falls. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 72, 1810–1816. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.18796 (2024).

National Health and Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Two-way referral standard of rehabilitation medical treatment for 8 common diseases or surgery. Chin. J. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation. 35, 446 (2013).

World Health Organization. Rehabilitation in health systems. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549974. [Accessed 2023-12-01].

Park, S., Xu, J., Manes, M. R., Carrier, A. & Osborne, R. What determinants affect inpatient satisfaction in a Post-acute Care Rehabilitation Hospital? Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 104, 270–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2022.08.008 (2023).

Hoff, A. et al. Integrated mental healthcare and vocational rehabilitation for people on sick leave with stress-related disorders: 24-month follow-up of the randomized IBBIS trial. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health. 49, 303–308. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.4084 (2023).

Scerri, A., Innes, A. & Scerri, C. Healthcare professionals’ perceived challenges and solutions when providing rehabilitation to persons living with dementia-A scoping review. J. Clin. Nurs. 32, 5493–5513. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16635 (2023).

Xue, K., Lv, X. & Wang, Y. Reliability and validity test and application value of hierarchical diagnosis and treatment rating scale in rehabilitation medicine in stroke patients. Chin. J. Gen. Pract. 21, 1215–1219. https://doi.org/10.16766/j.cnki.issn.1674-4152.003087 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Evaluation of the disability assessment Longshi scale: a multicenter study. J. Int. Med. Res. 48, 0300060520934299. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060520934299 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Reliability of Longshi scale with remote assessment of smartphone video calls for stroke patients’ activities of daily living. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 32, 106950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2022.106950 (2023).

Xue, K., Lv, X. & Yulong, W. Reliability and validity test and application value of hierarchical diagnosis and treatment rating scale in rehabilitation medicine in stroke patients. Chin. J. Gen. Pract. 21, 1215–1219. https://doi.org/10.16766/j.cnki.issn.1674-4152.003087 (2023).

Yunnan Provincial Medical Security Bureau. Notice on the Standardization of Limited Payment Conditions for Basic Medical Insurance Rehabilitation Programs. https://ylbz.yn.gov.cn/index.php?c=show&id=1547. (2020). [Accessed 2024-08-20].

Shandong Province Government. Notice on Implementing the Inclusion of New Partial Medical Rehabilitation Programs in the Basic Medical Security Payment Scope in Our Province. http://www.shandong.gov.cn/art/2016/9/14/art_305280_10331752.html. (2016). [Accessed 2024-08-20].

Hangzhou Medical Security Bureau. Notice on Further Strengthening the Management of Medical Insurance for Partial Diagnosis and Treatment Service Items of Designated Medical Institutions. https://www.hangzhou.gov.cn/art/2021/11/26/art_1229063383_1804953.html (2021). [Accessed 2024-08-20].

Hainan Provincial Department of Human Resources and Social Security and Seven Other Departments Issue. Notice on Several Measures to Further Promote Work Injury Rehabilitation in the Province. (2024). http://hrss.hainan.gov.cn/hrss/0503/202405/322c69c36c6b4af3a644aada4350bb1c.shtml. [Accessed 2024-08-20].

Shenzhen Medical Security Bureau Shenzhen Municipal Health Commission. Notice on Further Standardizing Rehabilitation Medical Services Related Work. http://hsa.sz.gov.cn/zwgk/zcfgjzcjd/gfxwj/content/post_9498864.html. (2022). [Accessed 2024-08-20].

Nunnally, J. C. Psychometric Theory 2nd edn (McGraw-Hill, 1978).

Neiri Santos, J. P. A. S. et al. J Ramalho-Santos. Cronbach’s alpha: a tool for assessing the reliability of scales. Exten J. 37, 1 (1999).

Hoyle, R. H. in In Handbook of Applied Multivariate Statistics and Mathematical Modeling. 465–497 (eds Howard, E. A., Tinsley, Steven, D. & Brown) (Academic, 2000).

PrudonP Confirmatory Factor Analysis as a Tool in Research using questionnaires: a critique. Compr. Psychol. 4, 03CP0410. https://doi.org/10.2466/03.CP.4.10 (2015).

Xia, Y., Yang, Y. R. M. S. E. A., CFI & TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: the story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behav. Res. Methods. 51, 409–428. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1055-2 (2019).

Gallais, B., Gagnon, C., Forgues, G., Côté, I. & Laberge, L. Further evidence for the reliability and validity of the fatigue and daytime sleepiness scale. J. Neurol. Sci. 375, 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2017.01.032 (2017).

Roberts, P., Priest, H. & Traynor, M. Reliability and validity in research. Nurs. Standard. 20, 41–45 (2006).

Léauté-Labrèze, C. et al. The infantile Hemangioma Referral score: a validated Tool for Physicians. Pediatrics. 145 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-1628 (2020).

Ejtehadi, M., Amrein, S., Hoogland, I. E., Riener, R. & Paez-Granados, D. Learning activities of Daily living from unobtrusive Multimodal wearables: towards Monitoring Outpatient Rehabilitation. IEEE Int. Conf. Rehabil Robot. 2023, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/icorr58425.2023.10304743 (2023).

Ribeiro, R. et al. The effectiveness of nursing Rehabilitation interventions on Self-Care for older adults with respiratory disorders: a systematic review with Meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 20 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146422 (2023).

Pelletier, R., Purcell-Levesque, L., Girard, M. C., Roy, P. M. & Leonard, G. Pain Intensity and functional outcomes for activities of Daily Living, Gait and Balance in older adults accessing Outpatient Rehabilitation services: a retrospective study. J. Pain Res. 13, 2013–2021. https://doi.org/10.2147/jpr.S256700 (2020).

Miller, D., Mugridge, S., Elder, M., Holt, M. & Liu, K. P. Y. Student-led activities of daily living group program in a hospital inpatient rehabilitation setting. Aust Occup. Ther. J. 71, 486–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12937 (2024).

Natsume, K. et al. Factors influencing the improvement of activities of Daily Living during Inpatient Rehabilitation in newly diagnosed patients with Glioblastoma Multiforme. J. Clin. Med. 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11020417 (2022).

Ikeda, T. & Tsuboya, T. Intensive In-hospital Rehabilitation after hip fracture surgery and activities of Daily living in patients with dementia: retrospective analysis of a Nationwide Inpatient database. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 101, 171–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2019.08.487 (2020).

World Health Organization, WHO Guideline on Self-Care Interventions for Health and Well-Being (World Health Organization © World Health Organization. ISBN-13: 978-92-4-003090-9. (2021) (2021).

Schmitz, K. H. et al. An initiative to implement a triage and referral system to make exercise and rehabilitation referrals standard of care in oncology. Support Care Cancer. 32, 259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08457-8 (2024).

Conradie, T., Charumbira, M., Bezuidenhout, M., Leong, T. & Louw, Q. Rehabilitation and primary care treatment guidelines, South Africa. Bull. World Health Organ. 100, 689–698. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.22.288337 (2022).

Mo, L. et al. Referral criteria to specialist palliative care for patients with dementia: a systematic review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 69, 1659–1669. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17070 (2021).

Karjala, J. & Eriksson, S. Inter-rater reliability between nurses for a new paediatric triage system based primarily on vital parameters: the Paediatric Triage Instrument (PETI). BMJ Open. 7, e012748. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012748 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the individuals from each medical institution for their support and advice in provision of data.

Funding

This research was supported by Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (No. SZSM202111010), Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline Construction Fund (No. SZXK048), Shenzhen Portion of Shenzhen-Hong Kong Science and Technology Innovation Cooperation Zone, project No.HTHZQSWS- KCCYB-2023060.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ruixue Ye: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing- Original draft preparation, Investigation. Yan Gao: Visualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation. Kaiwen Xue: Data curation, Investigation. Zeyu Zhang: Visualization, Investigation.Jianjun Long: Visualization, Investigation.Yawei Li: Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Validation.Guo Dan: Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Validation.Yongjun Jiang: Supervision, Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Resources.Yulong Wang: Supervision, Validation, Project administration, Resources, Funding acquisition.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Our studies were approved by the Second People’s Hospital of Shenzhen Ethical Review Board (approval number of studies: 2023-226-02PJ). Participants were informed of the nature and purpose of the study before providing written consent. All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, R., Gao, Y., Xue, K. et al. The reliability and validity of a novel clinical tool for distributing rehabilitation patients: a multicenter cross-sectional study in China. Sci Rep 14, 27456 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79113-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79113-8