Abstract

Channel encroachment intensifies competition among channels and changes the relationships within the supply chain. This study examines the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment decision and its impact when it has already operated a platform reselling channel and a retailer channel on the platform. Equilibrium results reveal that the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment triggers a competition effect, leading to a reduction in market demand for both the platform’s reselling channel and the retailer’s channel, as a larger share of the market shifts toward the manufacturer’s agency channel. To compensate for the losses in sales experienced by the platform and retailer, the manufacturer lowers the wholesale price. The manufacturer consistently benefits from channel encroachment and a Pareto improvement region exists, allowing all supply chain participants to improve their profits. The model is extended to consider sequential decision-making and asymmetric substitution. In comparison, under sequential decision-making, the manufacturer tends to focus more on the competitive effects of channel encroachment, leading to a reduction in channel sales. However, this approach only enhances the manufacturer’s agency profit when the retailer’s substitution capability is relatively strong. The manufacturer faces greater competitive pressure from the retailer under asymmetric channel substitution. Although the manufacturer increases the wholesale price and adjusts sales across channels according to the competitive situation, its profits are always lower than in the symmetric substitution case. The presence of a Pareto improvement region in the extended model confirms the robustness of our findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The choice of channel structure is a pivotal decision in manufacturers’ operational strategies, directly influencing product sales, market penetration, brand recognition, and consumer satisfaction. With the rise of platform retail, manufacturers can engage directly with consumers through platforms, reducing sales costs and enhancing transaction convenience. Manufacturers frequently adopt dual or multi-channel strategies on the same platform. For example, on JD.com, companies like Huawei and Apple adopt a dual-channel model consisting of platform reselling and retailer channels, while Xiaomi and OPPO introduce a manufacturer agency channel based on the above-mentioned dual channels. Figure 1 shows Xiaomi’s three typical channels on JD.com. From the timeline of channel activation, it can be seen that Xiaomi added a manufacturer agency channel on top of the existing platform reselling channel and retailer channel.

In online retailing, platforms not only function as traditional retailers but also serve as marketplaces for third-party sellers. According to Marketplace Pulse1, third-party sellers comprise 60% of the overall units sold on Amazon and account for an even higher share of GMV, underscoring the significant role of third-party sellers in 2023. Similarly, JD.com’s 2023 Annual Report highlighted an annual revenue of 1.0847 trillion yuan, with a 188% year-on-year increase in the number of third-party merchants and a 4.3-fold rise in new merchant additions 2. For the platform, sellers other than itself are third-party sellers, including manufacturers and their retailers. When they sell through the platform’s agency channel, they must pay a commission fee, which contributes to the platform’s primary source of profits.

Manufacturer encroachment, as discussed by Arya et al.3 and Huang et al.4, refers to a manufacturer establishing a direct channel within an existing distribution network. A direct channel typically refers to an online sales channel established by the manufacturer3,3,4,6. A key feature of the direct channel is its ability to streamline the supply chain while fostering competition between the manufacturer and the retailer. In platform retail, the manufacturer’s agency channel mimics direct sales with lower setup costs, creating a relationship with the platform that is both competitive and cooperative through commission agreements. To some extent, a manufacturer selling products directly through a platform can be considered a particular form of channel encroachment. In this article, this phenomenon is referred to as manufacturer agency channel encroachment. Reconsidering Xiaomi’s channel strategy raises an important question: Should manufacturers like Huawei and Apple, which already operate dual channels on JD.com, engage in manufacturer agency channel encroachment?

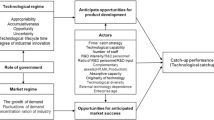

In this paper, we examine the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment decision and its impact in a multi-channel retail environment, where the manufacturer simultaneously operates a platform reselling channel and a retailer channel on the same platform. Our analysis highlights that the stability of the channel structure is contingent on the platform’s commission rate and the retailer’s substitution capability. Agency channel encroachment introduces a competition effect, reducing demand for both the platform’s reselling and retailer channels while shifting market share toward the manufacturer’s agency channel. Although this results in declining reselling sales for the platform, its overall revenue may increase due to the commission revenue effect. Conversely, the retailer faces greater challenges as its market share and profitability decrease. To counteract the losses of the platform and retailer, the manufacturer lowers the wholesale price, redistributing market demand and ultimately strengthening its position. We identify a Pareto improvement region where all supply chain participants can enhance their profits. Furthermore, the research extends the model by considering sequential decision-making and asymmetric channel substitution. Under sequential decision-making, the manufacturer focuses more on the competition effect of channel encroachment. The manufacturer always reduces the agency channel sales and also lowers wholesale price when the retailer’s substitution ability is strong. Still, such adjustments only result in higher profit for the manufacturer when the retailer’s substitution ability is strong. In contrast to the symmetric channel substitution scenario, the manufacturer faces greater competitive pressure from the retailer under asymmetric channel substitution. Although the manufacturer increases the wholesale price and adjusts sales across channels according to the competitive situation, its profits are always lower than in the symmetric substitution case.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section “Related literature” reviews the relevant literature. Section “Model setup” outlines the model, including the assumptions and notations. Section “Model analysis” presents our central findings. Section “Model extensions” extends the model to consider sequential decision-making and asymmetric channel substitutability. Section “Conclusions and future research directions” summarizes the main results and managerial insights and proposes some future research directions.

Related literature

Sales mode selection

In platform retail, reselling and agency selling are the two predominant modes. Early research on platform retail primarily focused on what types of sales modes platforms offer to manufacturers. A stream of studies has focused on the platform’s sales mode selection in the context of manufacturer competition, platform competition, or product difference7,7,8,9,10,12. Under the reselling mode, the platform first purchases goods from the manufacturer before selling them, whereas, in the agency mode, the manufacturer sells products directly through agreements with the platform. Abhishek et al.7 highlighted that the key difference between these two modes lies in the decision-making authority over product sales prices. Tian et al.13 argued that the reselling mode can mitigate competition, while the agency sales mode can reduce double marginalization. Wei and Dong14 and Mantin et al.15 examined the strategic role of platform open market strategies, providing support for the platform’s adoption of hybrid sales models. Liu et al.16 and Song et al.17 further studied the manufacturer’s sales mode choice on hybrid platforms.

Early research usually assumes that a manufacturer sells the same product through either platform reselling or agency channel, but not both. However, in practice, many manufacturers sell the same products through both channels of the same online platform. Ha et al.18 studied a manufacturer’s channel structures on one platform. A dual channel with both reselling and agency channels is considered. It revealed that a wholesale price effect and a channel flexibility effect in a dual channel can mitigate the inefficiency caused by double marginalization. Li et al.19 explored the platform’s information-sharing strategy when the manufacturer has both agency and retailer channels on the same platform. It is common in practice for manufacturers to establish multiple sales channels on the same platform. This paper extends the work of Ha et al.18 and Li et al.19 by examining the manufacturer’s sales through three channels on the same platform. It analyzes the conditions for multi-channel strategies and their impact on supply chain partners.

Manufacturer’s channel strategy

Another stream of literature relevant to this study focuses on manufacturers’ channel strategies. Balasubramanian20 and Ferrer and Swaminathan21 focused on the competitive effects of encroachment. Chiang et al.22, Tsay and Agrawal6, Cattani et al.5, Arya et al.3, Cai23, Cai et al.24 explored the impact of manufacturer’s introducing online direct channel on a traditional offline channel. These studies found that direct channels may not necessarily harm retailer profits and can even be beneficial to both parties under certain conditions. Abhishek et al.7, Shen et al.25, Chen et al.26, and Yan et al.27 studied the competition and cooperation between the offline channel and the platform channel. They considered the impact of channel spillover effects, platform entry costs, and channel competition on manufacturer strategies. Ryan et al.28, Wang et al. 29, and Yi et al.30 studied decision-making in the context of competition between the direct channel and the platform channel. Pu et al.31 and Zhen et al.32 examined the competition among offline, direct, or/and platform channels.

In the studies above, the direct channel refers to the manufacturer’s self-established online channel, while the platform channel only considers a single contract between the manufacturer and the platform. Ha et al.18,33 and Luo et al.34 viewed the platform reselling channel and agency channel as two distinct channels, studying whether a manufacturer should adopt a single-channel or dual-channel strategy, highlighting the wholesale price effect and channel transfer effect under the dual-channel mode. Besides, research has gradually shifted from traditional offline channels to platform channels, moving from dual-channel structures to triple-channel structures. To the best of our knowledge, only Ha et al.33 considered the case when the manufacturer encroaches by selling through the agency channel in addition to the existing platform reselling channel. Only Ryan et al.28, Zhen et al.32, and Zhang et al.35 considered scenarios where a manufacturer simultaneously operates in three distribution channels, providing a theoretical basis for competition and coordination under the triple-channel structure. Similar to18,33 and Luo et al.34, we treat different contracts between a manufacturer and the same platform as distinct distribution channels. This perspective adds complexity to the relationships among the manufacturer, platform, and retailer. This paper examines the impact of manufacturer agency channel encroachment, which results in a triple-channel structure that is widely observed in practice. However, existing research has not addressed this issue.

Coopetition relationship among supply chain members

This paper also relates to research on cooperative relationships among supply chain members. Existing studies on supply chain coopetition structures primarily focus on the relationships between Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) and Contract Manufacturers (CMs)36,35,38. This paper also relates to research on coopetition relationships among supply chain members. Existing studies on supply chain coopetition structures primarily focus on the relationships between Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) and Contract Manufacturers (CMs)36,35,38. In hybrid platforms, coopetition manifests in multiple ways. A significant body of literature has examined issues related to logistics sharing39,40,41 information sharing4,18,19,42,43 between platform and manufacturer. Research findings indicate that, as a strategic decision, sharing behavior among supply chain members can enhance overall performance under certain conditions.

Additionally, manufacturer agency channel encroachment creates a unique coopetition relationship. Recent literature, such as Shen et al.25, Tan et al.44, Tian et al.13, and Zhang et al.45, consider the commission rate as a revenue-sharing contract between the platform and the manufacturer. Manufacturer agency channel encroachment not only introduces competition between the manufacturer and the platform but also enables the platform to benefit from a revenue-sharing mechanism established through commission rates. Building on the previous research, we consider the equilibrium decision changes for the manufacturer and the platform in the context of manufacturer agency channel encroachment, particularly focusing on how variations in commission rate influence decisions.

Model setup

On an online platform, a manufacturer distributes products through both a platform reselling channel and a retailer channel. For the manufacturer, platform, and retailer are its resellers. For the platform, the retailer is not only a competitor but also a profit source. The retailer is required to pay a commission rate \(r\) to the platform for the reach of the marketplace. In this paper, \(r\) is treated as an exogenous variable, constrained within \(0<r<0.5.\) This range reflects typical industry practices where platforms impose uniform commission rates for product categories before manufacturers finalize their channel strategies. For instance, in 2020, Amazon applied an 8% commission rate for personal computer products and 15% for books, with most categories ranging from 6 to 17%. Similarly, JD.com’s rates typically vary from 2 to 10%, while Tmall sets rates at 5% for shoes and 2% for books and audio-visual products.

One strategic decision the manufacturer faced is whether to introduce an agency channel on the platform. Manufacturer agency channel encroachment has multiple impacts on the supply chain and market dynamics. First, by selling directly to consumers, the manufacturer gains greater control over pricing and broader market demand, thereby increasing competitive advantage. Second, the platform benefits from the additional commission fee channel but faces the challenge of competing with the manufacturer, creating a complex coopetition relationship. The retailer, however, experiences significant competition, with consumers often opting for a lower price or service convenience. Overall, agency channel encroachment intensifies channel conflict, complicates supply chain relationships, and prompts shifts in market structure and decisions.

Singh and Vives46 proposed using a quadratic utility function to derive a linear demand-price relationship. In this study, we employ an inverse demand function to model this relationship. Specifically, assuming a monopolistic manufacturer selling products through both the platform reselling channel and the retailer channel, there exists a quantity competition dynamic between these channels. Let \({q}_{1}^{N}\) and \({q}_{3}^{N}\) represent the quantities ordered through the platform and retailer, respectively. The inverse demand functions for these channels are formulated as follows:

According to Liu et al.16, we assume a market size of 1 to simplify model calculations, considering that both the platform and retailer target the same customer base. Additionally, as highlighted by He et al. (2020), platforms generally exhibit higher quality and trustworthiness compared to retailers. Building on this, we assume that the platform reselling channel can fully substitute the retailer channel, whereas the retailer’s channel can only partially substitute the platform reselling channel. To quantify this substitution relationship, we introduce a substitution rate \(\beta\), where \(0<\beta <1\). The parameter \(\beta\) represents the substitution capability of the retailer channel for the platform reselling channel, reflecting the competitive dynamics between the channels. This demand function is a common feature in the literature on manufacturer encroachment, as explored in studies by Arya et al.3, Ha et al.42, and Li et al.47,48. For simplicity and without loss of generality, we assume that the manufacturer’s product production costs and channel operation costs are both zero. This assumption does not compromise the main conclusions drawn in this paper. Table 1 lists the relevant symbols used in our model.

This study employs the Stackelberg game to simulate the strategic interactions among the manufacturer, the platform, and the retailer. The decision-making process unfolds across three stages:

-

Stage 1 As the market leader, the manufacturer decides whether to engage in agency channel encroachment.

-

Stage 2 Acting as the Stackelberg leader, the manufacturer sets the wholesale price offered to both the platform and the retailer.

-

Stage 3 The platform and the retailer, as followers, simultaneously determine the quantity of products to sell at the given wholesale price. If the manufacturer opts for encroachment, it also decides the sales quantity through its channel in this stage.

The timeline of the game is depicted in Fig. 2.

Based on the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment decision, two potential market structures may emerge. In Scenario N, the manufacturer sells products with two established channels, while in Scenario E, three channels are utilized. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the solid lines indicate the flow of the product, while dotted lines represent the implicit transmission of commissions.

Next, this study employs backward induction to ascertain the profit-maximizing decisions of supply chain members across different channel structures. Specifically, we analyze the impact of the retailer channel’s substitution capability and commission rate on these decisions. Subsequently, we compare the equilibrium decisions and profits under different channel structures to examine the existence of the Pareto region resulting from manufacturer channel encroachment.

Model analysis

No channel encroachment case

When the manufacturer refrains from agency channel encroachment, products are distributed to customers through the platform reselling channel and the retailer channel. In this scenario, given the wholesale price, the platform and the retailer determine their sales quantities \({q}_{1}^{N}\) and \({q}_{3}^{N}\) to maximize their profits. The profit functions for the platform, the retailer, and the manufacturer are respectively:

The platform’s profit consists of revenue from reselling and commission from the agency channel. After deducting the procurement costs, the platform’s profit is determined. The retailer’s profit is formed from sales through the agency channel, considering the wholesale price and commission cost. The manufacturer’s profit primarily arises from product wholesale. To ensure the stability of the channel structure, both \({q}_{1}^{N}>0\) and \({q}_{3}^{N}>0\) must hold. The profits from reselling products for both the platform and the retailer must be greater than zero. The implicit constraint condition is \(1-{q}_{1}^{N}-\beta {q}_{3}^{N}-{w}^{N}>0\) and \(\left(1-r\right)\left(1-{q}_{3}^{N}-{q}_{1}^{N}\right)-{w}^{N}>0\). Based on the assumptions regarding \(r\) and \(\beta\), the constraint conditions can be combined as \(0<{w}^{N}<\left(1-r\right)\left(1-{q}_{3}^{N}-{q}_{1}^{N}\right)\) and \({q}_{1}^{N}+{q}_{3}^{N}<1\). Using the backward induction method, we solve this model to obtain the equilibrium solution.

Lemma 1

Scenario N exists when \(0<r\le \frac{1}{2}\left(5-\sqrt{17}\right)\) and \(0<\beta <1\) or \(\frac{1}{2}\left(5-\sqrt{17}\right)<r<\frac{1}{2}\) and \(0<\beta <\frac{3-6r+{r}^{2}}{1-r}\). The equilibrium decisions in the absence of agency channel encroachment are \({w}^{N*}=\frac{(1-r)(3-r-\beta )}{2(3-2r-\beta )}\), \({q}_{1}^{N*}=\frac{6+{r}^{2}-r(3-2\beta )-5\beta +{\beta }^{2}}{2(4-r-\beta )(3-2r-\beta )}\), \({q}_{3}^{N*}=\frac{3+{r}^{2}-r(6-\beta )-\beta }{2(4-r-\beta )(3-2r-\beta )}\).

Lemma 1 illustrates Scenario N only exists when either the commission rate is low or when the commission is high, but channel competition is relatively weak. Under these conditions, the retailer can achieve profit, ensuring the stability of the channel structure. Under the assumption that the retailer channel only partially substitutes the platform reselling channel, the retailer has to compete with a lower price. Next, we analyze the impact of commission rate and the retailer channel’s substitution capability on the decisions of supply chain entities.

Define \({q}^{N*}={q}_{1}^{N*}+{q}_{3}^{N*}\) to denote the overall sales in Scenario N. By taking the first-order derivative of total sales concerning the commission rate, we obtain \(\frac{\partial {q}^{N*}}{\partial r}=-\frac{1}{2{\left(4-r-\beta \right)}^{2}}<0\), which always holds. Additionally, differentiating individual sales decisions concerning the commission rate reveals that \(\frac{\partial {q}_{1}^{N*}}{\partial r}>0\), \(\frac{\partial {q}_{3}^{N*}}{\partial r}<0\), and \(\frac{\partial {w}^{N*}}{\partial r}<0\). That is, as the commission rate increases, the platform’s sales rise, while the retailer’s and overall sales decrease, and the manufacturer lowers the wholesale price. This is driven by two effects: the cost effect on the retailer and the revenue effect on the platform. A higher commission rate squeezes the retailer’s profit margins, discouraging sales and thereby reducing demand in the retailer channel. On the platform side, the platform adjusts its strategy to balance product sales revenue against commission income. To mitigate the negative impact of higher commissions on the retailer, the manufacturer lowers the wholesale price. This action encourages the platform to increase its sales, leading to a shift in market demand from the retailer channel to the platform reselling channel.

Moreover, the wholesale price set by the manufacturer increases with \(\beta\) (i.e., \(\frac{\partial {w}^{N*}}{\partial \beta }>0\)) , and overall sales decrease (i.e., \(\frac{\partial {q}^{N*}}{\partial \beta }=-\frac{1}{2{\left(4-r-\beta \right)}^{2}}<0\)). It is noteworthy that as the retailer’s substitution capability strengthens, which intensifies channel competition, the manufacturer’s total product sales do not decrease. The distribution of sales between the platform reselling channel and the retailer channel depends on the commission rate. If the commission rate is high, more demand shifts to the platform reselling channel due to the high cost in the retailer channel. Conversely, if the commission rate is low, more demand moves to the retailer channel as the platform prefers to increase commission revenue. This dynamic reflects the balancing act of both the retailer, which weighs commission costs against sales revenue and the platform, which balances commission income and product sales. In response, the manufacturer raises the wholesale price to sustain its profitability. Finally, defining \({t}_{1}^{N}=\frac{{q}_{1}^{N*}}{{q}_{1}^{N*}+{q}_{3}^{N*}}\) as the sales contribution of the platform reselling channel, we find that \({t}_{1}^{N}=\frac{6-3r+{r}^{2}-5\beta +2r\beta +{\beta }^{2}}{\left(3-r-\beta \right)\left(3-2r-\beta \right)}>\frac{1}{2}\). This indicates that the platform reselling channel consistently dominates in terms of sales contribution in Scenario N.

The encroachment case

When the manufacturer engages in channel encroachment through an agency channel, the substitution effects between the platform reselling channel and the agency channels become more complex. To quantify this, we introduce a parameter \(\eta\) to represent the substitution rate of the retail channel for the manufacturer agency channel, and we assume \(0<\beta \le \eta <1,\) which means the retailer channel is no more effective than the manufacturer agency channel. Additionally, the manufacturer agency channel is assumed to be as efficient as the platform reselling channel, and both can fully replace the retailer channel. The inverse demand function can be expressed as:

To simplify calculations, we assume \(\eta = \beta\), indicating that the retailer channel has the same substitution capability for both the platform reselling and the manufacturer’s agency channels. From the demand function, it can be observed that when both channel sales are non-negative, the retailer channel has the lowest price. The profits for the platform, the manufacturer, and the retailer are defined as follows:

The platform’s revenue is primarily derived from product sales and commissions earned from the agency channel, whereas the retailer’s profit only originates from product sales. The manufacturer’s profit, however, comes from both wholesale and direct sales of the product. To ensure channel structure stability, the potential constraints are as follows: (1) \({p}_{3}^{E}>0\), which guarantees that the sales prices across all channels are positive. (2) \(\left(1-r\right){p}_{3}^{E}-{w}^{E}>0\), which ensures the retailer’s profit remains positive, and consequently, the platform’s reselling profit is also positive. Additionally, the product sales for all channels must remain greater than zero. Employing backward induction to solve this model provides equilibrium sales quantities for each channel and determines the wholesale price.

Lemma 2

Equilibrium decisions when the manufacturer engages in agency channel encroachment are as follows:

Next, analyzing the effect of commission rate changes on equilibrium decisions, we find \(\frac{\partial {\text{w}}^{\text{E}*}}{\partial \text{r}}<0\), \(\frac{\partial {\text{q}}_{1}^{\text{E}*}}{\partial \text{r}}<0\) and \(\frac{\partial {\text{q}}_{3}^{\text{E}*}}{\partial \text{r}}>0.\) This indicates that the optimal wholesale price decreases with increasing commission rate, similar to Scenario N. However, unlike the no-encroachment case, the sales decisions for the platform reselling channel and the retailer channel exhibit opposite trends. As the commission rate rises, platform reselling channel sales decrease, suggesting that the income effect of the commission outweighs the competitive effect of agency channel encroachment. Despite the retailer’s lower channel efficiency, encroachment leads to increased sales in the retailer’s channel as commission rates increase. This may be due to the decreasing willingness of both the platform and manufacturer to sell through their respective channels, leading to a shift in demand towards the retailer’s channel. There exists a critical value given by \({\beta }_{1}^{E}=\frac{6+2r-3{r}^{2}}{4-{r}^{2}}-2\sqrt{\frac{5-6r+2{r}^{2}}{{\left(4-{r}^{2}\right)}^{2}}}\). If \(0<\beta \le {\beta }_{1}^{E}\), the quantity sold through the manufacturer channel \(\frac{\partial {q}_{2}^{E*}}{\partial r}\ge 0\). Otherwise, \(\frac{\partial {q}_{2}^{E*}}{\partial r}<0\). This reveals that the sales in the manufacturer channel do not vary monotonically with the commission rate. When the retailer’s substitution capability is weak, the manufacturer may increase sales through the agency channel due to its superior efficiency. Conversely, when the retailer’s substitution capability is strong, the manufacturer reduces agency channel sales to manage channel conflict more effectively.

Similarly, we analyze the effect of changes in \(\beta\) on the equilibrium decisions. We can find \(\frac{\partial {w}^{E*}}{\partial \beta }>0,\) \(\frac{\partial {q}_{1}^{E*}}{\partial \beta }<0,\) and \(\frac{\partial {q}_{3}^{E*}}{\partial \beta }<0.\) This indicates that as the substitution capability of the retailer improves, the manufacturer increases the wholesale price when engaging in encroachment while both the sales in the platform reselling channel and the retailer channel decrease, reversing the trend observed in Scenario N. This reflects the model’s assumption that the manufacturer’s agency channel fully substitutes for both the platform and the retailer channels, while the retailer channel only partially substitutes for the others. As the retailer’s substitution capability increases, the manufacturer’s strategy of raising the wholesale price reduces unit profits for both the platform and the retailer due to heightened competition, thereby diminishing their sales incentives. Additionally, there exist critical values \({\beta }_{2}^{E}\) and \({r}_{1}^{E}\) such that when \(0<\beta \le {\beta }_{2}^{E}\) and \(0<r<{r}_{1}^{E},\) or \({\beta }_{2}^{E}<\beta <1,\) the sales quantity in the manufacturer channel increases with \(\beta,\) \(\frac{\partial {q}_{2}^{E*}}{\partial \beta }>0.\) Otherwise, \(\frac{\partial {q}_{2}^{E*}}{\partial \beta }<0,\) where \({\beta }_{2}^{E}=\frac{1}{19}\left(29-4\sqrt{30}\right),\) \({r}_{1}^{E}=\frac{5-\beta }{3-\beta }-\sqrt{\frac{17-18\beta +5{\beta }^{2}}{{\left(3-\beta \right)}^{2}}}.\) This illustrates that while sales quantities for the platform and retailer decrease as the substitution rate increases, market demand does not uniformly shift toward the manufacturer agency channel. In cases where the channel substitution capability is relatively weak or the commission rate is excessively high, the manufacturer may strategically reduce agency channel sales to mitigate potential conflicts.

Similarly, Define \({t}_{1}^{E}=\frac{{q}_{1}^{E*}}{{q}_{1}^{E*}+{q}_{2}^{E*}+{q}_{3}^{E*}}\) and \({t}_{2}^{E}=\frac{{q}_{2}^{E*}}{{q}_{1}^{E*}+{q}_{2}^{E*}+{q}_{3}^{E*}}\) to represent the sales contribution rate of the platform reselling channel and the manufacturer agency channel to overall sales. We find \(\frac{\partial {t}_{1}^{E}}{\partial r}<0,\) \(\frac{\partial {t}_{1}^{E}}{\partial \beta }<,0\) \(\frac{\partial {t}_{2}^{E}}{\partial r}<,0\) and \(\frac{\partial {t}_{2}^{E}}{\partial \beta }>0.\) As \(r\) and \(\beta\) increase, \({t}_{1}^{E}\) decreases, and solving it gives \({t}_{1}^{E}<\frac{1}{9}\), which is significantly lower than Scenario N. \({t}_{2}^{E}\) decreases with rising \(r\) but increases with \(\upbeta\) β, and solving it gives \({t}_{2}^{E}>\frac{17}{21}\), indicating that the manufacturer agency channel consistently contributes a large share of sales. This indicates that in Case E, more demand is captured by the manufacturer agency channel, thereby strengthening the manufacturer’s market power.

Equilibrium analysis

To analyze the effects of the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment, we compared the optimal decisions under scenarios N and E. By contrasting the profits in these two modes, we examined the manufacturer’s equilibrium decisions and identified the Pareto improvement regions for the supply chain.

Proposition 1

Comparison of equilibrium decisions between Case N and Case E:

-

(i)

The equilibrium wholesale price in Case E is no more than that under Case N: \({{\varvec{w}}}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}\le {{\varvec{w}}}^{{\varvec{N}}\boldsymbol{*}}.\) Furthermore,\(\frac{\partial {{\varvec{w}}}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}}{\partial {\varvec{r}}}<\frac{\partial {{\varvec{w}}}^{{\varvec{N}}\boldsymbol{*}}}{\partial {\varvec{r}}}<0,\frac{\partial {{\varvec{w}}}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}}{\partial{\varvec{\beta}}}>\frac{\partial {{\varvec{w}}}^{{\varvec{N}}\boldsymbol{*}}}{\partial{\varvec{\beta}}}>0\), indicating that changes in commission rate and substitution ability have a more substantial positive effect on the wholesale price under Case E.

-

(ii)

The sales quantity through the platform reselling channel under case E is no more than that under case N: \({{\varvec{q}}}_{1}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}\le {{\varvec{q}}}_{1}^{{\varvec{N}}\boldsymbol{*}}\). There exists a critical value \({{\varvec{r}}}_{1}\) such that if \(0<{\varvec{r}}\le {{\varvec{r}}}_{1}\), the sales quantity through the retailer channel in case E is no more than case N,\({{\varvec{q}}}_{3}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}\le {{\varvec{q}}}_{3}^{{\varvec{N}}\boldsymbol{*}}\); otherwise, \({{\varvec{q}}}_{3}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}>{{\varvec{q}}}_{3}^{{\varvec{N}}\boldsymbol{*}}\).

-

(iii)

The total sales quantity under case E is greater than case N, \({{\varvec{q}}}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}\ge {{\varvec{q}}}^{{\varvec{N}}\boldsymbol{*}}\). However, the sales in platform reselling and the retailer channels in case E is less than that in case N, \({{\varvec{q}}}_{1}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}+{{\varvec{q}}}_{3}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}<{{\varvec{q}}}^{{\varvec{N}}\boldsymbol{*}}\).

To analyze Proposition 1, we can break down the results by looking at the underlying factors affecting wholesale prices, sales quantities, and the effect of the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment.

Proposition 1(i) demonstrates the equilibrium wholesale price in Case E is lower than or equal to Case N. Previous studies3,18 have shown that the introduction of a direct channel alongside an existing resale channel tends to decrease the wholesale price in the resale channel. Proposition 1(i) extends this theory by illustrating that similar price effects persist even when a manufacturer operates through both platform reselling and retailer channels simultaneously. Due to the competition effect introduced by agency channel encroachment, the manufacturer lowers the wholesale price to incentivize the platform and retailer to continue selling despite increased competition from the manufacturer’s direct channel. The commission rate has a negative effect on the wholesale price in both cases. However, the impact is stronger in Case E, as the manufacturer must adjust more aggressively to balance the competition between channels. Conversely, the substitution ability has a positive effect on wholesale prices, but again, the manufacturer is more responsive in Case E, where there is a greater need to maintain balance between the channels.

Proposition 1(ii) asserts that manufacturer agency channel encroachment consistently reduces the sales volume of the platform reselling channel. This result is driven by two key factors: first, the manufacturer’s agency channel mitigates the double marginalization effect, diverting some of the sales that would have otherwise gone through the platform. Second, the platform earns increased commission revenue from agency channels, making it less reliant on product reselling. Conversely, the sales volume of the retailer channel decreases when the commission rate is relatively low and increases when it is relatively high. This pattern emerges because the manufacturer agency channel operates more efficiently than the retailer channel under lower commission rates. However, higher commission rates increase costs for the manufacturer channel, reducing its attractiveness and thereby shifting demand towards the retailer channel.

Proposition 1(iii) clarifies that following manufacturer agency channel encroachment, total product sales increase, indicating a demand expansion effect. However, the sales volumes of both the platform reselling channel and the retailer channel declined. This redistribution of sales among channels also reflects the competitive impact of agency channel encroachment and the higher efficiency of the manufacturer channel. Specifically, the increase in total sales primarily results from the demand expansion facilitated by channel encroachment. In contrast, the decline in channel sales is driven by intensified competition and the superior efficiency of the manufacturer agency channel.

Proposition 1 provides essential insights into the impact of manufacturer agency channel encroachment, highlighting several strategic considerations for businesses. First, the manufacturer can benefit by lowering wholesale prices to sustain sales in both platform reselling and retailer channels. This demonstrates that manufacturers can leverage pricing strategies to enhance channel competitiveness and increase market share. Second, the commission rate is the critical factor for the platform to balance revenue across different channels. Although sales in the platform’s reselling channel may decline, increased commission revenue from the agency channel can offset this loss. Lastly, while manufacturer agency channel encroachment introduces competition that affects both platform and retailer sales volumes, overall market demand expands. The manufacturer can capitalize on this demand expansion to enhance their multi-channel sales strategy and drive total sales.

Proposition 2

If \(0<r\le \frac{1}{2}\left(5-\sqrt{17}\right)\) and \(0<\beta <1\) or \(\frac{1}{2}\left(5-\sqrt{17}\right)<r<\frac{1}{2}\) and \(0<\beta <\frac{3-6r+{r}^{2}}{1-r}\), the manufacturer always benefits from agency channel encroachment, \({\pi }_{M}^{E}\ge {\pi }_{M}^{N}\).

Proposition 2 asserts that agency channel encroachment consistently leads to an increase in the manufacturer’s profit. This proposition is based on the assumption of zero encroachment costs. In practical scenarios where there are fixed costs associated with encroachment, manufacturers would only engage in channel encroachment if these costs are below a certain threshold relative to \(r\) and \(\beta\). The benefits stem from diversifying distribution avenues, thereby enabling the manufacturer to reach a broader customer base. Direct engagement with customers also enhances operational efficiency compared to managing dual channels. Importantly, regardless of the substitutability of the retailer channel, agency channel encroachment remains advantageous for the manufacturer when the commission rate is relatively low. The findings from Proposition 2 offer key managerial insights for the manufacturer considering agency channel encroachment. Encroachment can be highly profitable, particularly when the commission rate is low. By diversifying distribution channels and engaging directly with customers, the manufacturer can increase operational efficiency and expand their market reach.

Proposition 3

There exists a threshold \({r}_{P}^{1}\) such that when \({r}_{P}^{1}\le r\le \frac{1}{2}\left(5-\sqrt{17}\right)\) and \(0<\beta <1\) or \(\frac{1}{2}\left(5-\sqrt{17}\right)<r<\frac{1}{2}\) and \(0<\beta <\frac{3-6r+{r}^{2}}{1-r}\), the platform benefits from the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment, \({\pi }_{P}^{E}\ge {\pi }_{P}^{N}\).Otherwise \({\pi }_{P}^{E}<{\pi }_{P}^{N}\).

Proposition 3 identifies a threshold \({r}_{P}^{1}\) which defines conditions under which the platform benefits from the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment. When \(r\) and \(\upbeta\) fall within certain ranges, the platform’s profit under agency channel encroachment is greater than or equal to its profit without encroachment. This conclusion can be explained by the balance between the platform’s two main revenue sources: commission income from the agency channel and profit from reselling. When \(r\) is relatively low, the platform’s revenue from commissions is insufficient to offset the decline in product reselling. In such cases, the platform’s overall profit is negatively impacted. Higher commission rates make agency channel encroachment more beneficial to the platform. However, competition should not be too intense; severe competition may still lead to losses for the platform due to the high commission costs associated with agency channels, which ultimately reduces total sales. Proposition 3 provides valuable guidance for platform managers. To benefit from manufacturer agency channel encroachment, the commission rate is a crucial factor. When the commission rate is low, the platform’s profit may suffer due to reduced reselling revenue, but a higher commission rate can compensate by boosting commission income. However, the platform must also manage competition levels, as excessive competition could lead to a decrease in total sales. The key is to strike a balance between commission income and competition intensity to maximize profitability while sustaining healthy channel dynamics.

Proposition 4

There exists a critical value \({\beta }_{T}^{1}\) and \({r}_{T}^{1}\). When \({r}_{T}^{1}\le r<\frac{1}{2}\left(5-\sqrt{17}\right)\) and \(0<\beta \le {\beta }_{T}^{1}\) or \(\frac{1}{2}(5-\sqrt{17})\le r<\frac{1}{2}\) and \(0<\beta <\frac{3-6r+{r}^{2}}{1-r}\), the retailer benefits from manufacturer channel encroachment,\({\pi }_{T}^{E}\ge {\pi }_{T}^{N}\). Otherwise \({\pi }_{T}^{E}<{\pi }_{T}^{N}\).

Proposition 4 highlights that when the commission rate is low or the substitution rate is high, the retailer’s profit is harmed by the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment. This is because, at a lower commission rate, the manufacturer’s agency channel operates more efficiently, attracting a larger share of market demand and intensifying competition with the retailer. In addition, the platform’s reselling channel remains competitive, and the revenue gained by the platform from its reselling operations outweighs the commission from agency channels. However, when the commission rate exceeds a certain critical value, the platform is incentivized to reduce its reselling channel volume and depend more on commission income from agency channels. In response to higher commission rates, the manufacturer reduces the wholesale price to offset the higher costs imposed by the commission on the retailer. This is done to maintain retailer participation and balance sales between the channels. Despite the higher commission costs, the retailer can still profit because the platform’s reselling volume declines. The retailer becomes a relatively more attractive channel due to the manufacturer’s wholesale price adjustments and reduced competition from the platform. When the retailer has a strong substitution capability, its profit is more vulnerable to manufacturer agency channel encroachment. The intensified competition, combined with downward pressure on prices and shifting consumer demand, means that the retailer’s profit margins shrink, even if the manufacturer attempts to mitigate the situation by lowering wholesale prices. In summary, the retailer can only profit from the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment when the commission rate is relatively high and the retailer’s substitution capability is relatively weak. Proposition 4 suggests that the retailer should closely monitor both the platform’s commission rate and its substitution capability when facing the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment. When the commission rate is low, the retailer faces heightened competition and reduced market share, making it challenging to maintain profitability. However, when the commission rate increases, the retailer can benefit from the manufacturer’s lowered wholesale price and reduced competition from the platform’s reselling channel. A retailer with weak substitution capability is better positioned to profit, as it faces less intense competition and benefits from the manufacturer’s price adjustments.

Proposition 5

A Pareto region exists, as determined by the commission rate and channel substitution capability, where the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment benefits all the supply chain members.

The existence of a Pareto region is grounded in the balance of several key effects caused by the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment: Competition Effect, Commission Revenue Effect, Commission Cost Effect, and Demand Allocation Effect. Together, these effects define the conditions under which all parties might benefit or lose from the manufacturer’s channel encroachment.

When the manufacturer enters the agency channel, a competitive force is introduced, directly affecting the platform’s reselling channel and the retailer’s channel. Propositions 1 and 2 show that while total market demand increases under agency channel encroachment, the sales in the traditional platform and retailer channels decrease. The manufacturer agency channel captures a growing share of demand, reinforcing the manufacturer’s dominance in the market. The shifting of demand depends on \(\beta\). When \(\beta\) is low, demand transfers relatively smoothly, allowing all players to benefit. As \(\beta\) rises, however, the encroachment intensifies competition, with the manufacturer capturing more market share and the platform and retailer losing ground.

As seen in Propositions 1 and 3, the commission rate plays a dual role for the platform. On one hand, higher commissions directly raise the platform’s income from agency sales. The platform’s ability to compete through reselling is weakened, reducing direct competition with the retailer. When the commission rate is not too low, the platform can benefit from encroachment, as the income effect dominates the competitive pressure. Additionally, commission rate \(r\) also has a cost effect on the agency channels. In response to higher commission rates, the manufacturer reduces the wholesale price to keep both channels active. The retailer becomes a relatively more attractive channel due to the manufacturer’s wholesale price adjustments and sales decline in the platform reselling channel.

The retailer, manufacturer, and platform must carefully consider the commission rate and market competition when facing agency channel encroachment. Higher commission rates can benefit the platform by increasing commission revenue while encouraging the manufacturer to lower the wholesale price, making the retailer more competitive. However, intense competition driven by a high substitution rate may harm both the retailer and platform as market share shifts to the manufacturer’s agency channel. Businesses should aim to optimize commission structure and balance competitive forces to ensure all parties can benefit from encroachment within a Pareto region.

Figure 4 visually presents a comparative analysis of the profits for supply chain members before and after the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment across varying levels of commission rate and channel substitutability. The profit enhancement regions for the manufacturer are labelled as A, B, C, and D; for the platform as A and D; and for the retailer as A and B. Notably, Region A is designated as the Pareto improvement region, where all supply chain members simultaneously benefit from the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment. The boundaries of Region A are defined by the conditions that simultaneously improve the profits of both the platform and the retailer.

Model extensions

Sequential decision-making

In the foundational model, the platform, manufacturer, and retailer simultaneously determine their respective channel sales, implying that the decision-making process is synchronized and all parties possess symmetrical information at the time of making their decisions. However, the extended model introduces a sequential decision-making framework, where the manufacturer observes the platform and retailer’s sales decisions before determining its agency channel sales. This sequential decision-making framework does not imply a traditional form of market information asymmetry, such as unequal access to demand information. Instead, it reflects a dynamic information advantage created by the timing of decisions. In this structure, the manufacturer, acting after the platform and retailer, can leverage the observed decisions of the other parties to optimize its strategy. This timing-based advantage allows the manufacturer to respond more effectively to competitive behaviors from the other channels. By utilizing backward induction, this four-stage Stackelberg game can be systematically analyzed to clarify the manufacturer’s decision-making process after encroaching into the agency channel.

Lemma 3

Equilibrium decisions in sequential quantity decision-making are as follows.

Proposition 6

Comparison of optimal decisions between Case E and sequential decision-making:

-

(i)

The manufacturer tends to reduce its channel sales under sequential quantity decision-making, \({q}_{2s}^{E*}<{q}_{2}^{E*}\). There exists a critical value \({\beta }_{s}^{1}\), such that when \({\beta }_{s}^{1}\le \beta <1\), the total product sales are higher under sequential decision-making compared to Case E, \({q}_{s}^{E*}\ge {q}^{E*}\). Otherwise, \({q}_{s}^{E*}<{q}^{E*}\).

-

(ii)

There exists a critical value \({\beta }_{s}^{2}\) such that when \({\beta }_{s}^{2}\le \beta <1\), the wholesale price under sequential decision-making is lower than in Case E, \({w}_{s}^{E*}\le {w}^{E*}\). Otherwise, \({w}_{s}^{E*}>{w}^{E*}\).

-

(iii)

There exists a critical value \({\beta }_{s}^{3}\) such that when \({\beta }_{s}^{3}\le \beta <1\), the manufacturer’s profit under sequential quantity decision-making is higher than in Case E, \({\uppi }_{Ms}^{E*}\ge {\uppi }_{M}^{E*}\). Otherwise, \({\uppi }_{Ms}^{E*}<{\uppi }_{M}^{E*}\).Where \({\beta }_{s}^{1}<{\beta }_{s}^{2}<{\beta }_{s}^{3}=\frac{29-12r}{2(11-4r)}-\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{\frac{137-88r+16{r}^{2}}{{(11-4r)}^{2}}}\).

Proposition 6(i) suggests that the manufacturer reduces its channel sales in sequential decision-making. This occurs because, by making decisions sequentially, the manufacturer can observe the sales actions of both the platform and retailer before committing to its agency channel sales. This observational advantage allows the manufacturer to strategically reduce agency channel sales to prevent overly intense competition between channels. By reducing its agency sales, the manufacturer aims to maintain balance and minimize cannibalization of sales across different channels. Despite sales declines through the manufacturer agent channel, the overall sales may be higher under sequential decision-making when the channel substitutability is high. The manufacturer’s strategic reduction of agency sales allows for more efficient use of both the platform and retailer channels, avoiding market saturation and allowing for better product allocation across channels, which can lead to higher overall sales.

Proposition 6(ii) shows that in a highly competitive market, the wholesale price under sequential decision-making is lower than in Case E. In contrast, in a less competitive market, the wholesale price is higher. This is because, in a more competitive environment, the manufacturer anticipates aggressive strategies from the platform and retailer. By lowering the wholesale price, the manufacturer incentivizes both the platform and retailer to sell more, thereby potentially compensating for the reduced profit margin per unit through higher volumes. Conversely, in less competitive markets, where there is less pressure to drive up volumes, a higher wholesale price allows the manufacturer to enhance its profit margin while keeping its agency channel competitive.

Proposition 6(iii) demonstrates that sequential decision-making offers an advantage in a competitive market by allowing the manufacturer to respond to market signals more effectively. When competition is intense, reducing agency channel sales proves beneficial as it weakens the competition between channels and leads to improved profitability. By limiting agency sales, the manufacturer alleviates channel conflict, ensuring that the platform and retailer channels can function more effectively without oversaturation. This strategic reduction improves the overall efficiency of channel management and enhances the manufacturer’s profitability. However, in less competitive markets, this cautious approach of reducing agency channel sales can become counterproductive. In such cases, the conservative strategy may lead to missed opportunities as demand is not fully met, resulting in reduced profitability. Essentially, while sequential decision-making grants the manufacturer more information, the approach may be too conservative in less competitive environments, leading to a decrease in potential profits.

In competitive markets, sequential decision-making allows the manufacturer to optimize channel performance by reducing agency sales and strategically lowering wholesale prices. This approach helps prevent market oversaturation, mitigates intense competition, and ensures that all channels—platform, retailer, and agency—can coexist effectively. The manufacturer can benefit from higher overall sales and improved profitability by responding to the platform and retailer’s strategies. However, in less competitive markets, this cautious approach may lead to missed opportunities, as reduced agency sales might limit the ability to capitalize on available demand fully. Managers should carefully assess market competition levels before adopting sequential decision-making to balance competition and channel efficiency.

Proposition 7

In the context of sequential decision-making, a Pareto improvement region determined by the commission rate and channel substitutability still exists. Within this region, the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment can enhance profits for all supply chain members.

Proposition 7 explores the existence of a Pareto improvement region within the sequential decision-making framework. The manufacturer’s information advantage in sequential decision-making increases its ability to optimize profits at the expense of other supply chain members, particularly the retailer. By observing the retailer and platform’s actions, the manufacturer can anticipate how its decisions will influence downstream activities. This creates a power imbalance, leading to a reduction in the potential gains for other parties, especially the retailer. The retailer’s profit improvement conditions set the boundaries of this Pareto improvement region, meaning that if the retailer’s profit does not improve, the Pareto region shrinks further. As shown in Fig. 5, in Region A, all supply chain members benefit from the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment, creating a Pareto improvement. Within Region B, both the manufacturer and the platform can achieve profit improvements, but the retailer does not. Within Region C, only the manufacturer experiences profit enhancement.

Asymmetric channel substitution

In the basic model, we simplified calculations by assuming that the retailer has the same substitution rate for both the platform reselling channel and the manufacturer’s agency sales channel. Now, we consider the scenario of asymmetric channel substitution. Generally, it is believed that the platform reselling channel provides the best service to customers, followed by the manufacturer’s agency sales channel, with the retailer agency channel being the least favorable. When considering channel substitution capabilities, we assume that the retailer’s ability to substitute the manufacturer’s agency channel is higher than its ability to substitute the platform reselling channel, i.e., \(0<\beta <\eta <1\). Under these conditions, the product sales prices across the three channels have the following relationship: \({p}_{1a}^{E}>{p}_{2a}^{E}>{p}_{3a}^{E}\). Similarly, by using backward induction, we can determine the profit-maximizing decisions for the supply chain members.

Lemma 8

Equilibrium decisions under asymmetric channel substitution are as follows.

Proposition 8

Comparison of optimal decisions between case E and asymmetric channel substitution:

-

(i)

The total sales under asymmetric channel substitution are always lower than in case E, \({{\varvec{q}}}_{{\varvec{a}}}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}<{{\varvec{q}}}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}\).There exist critical values \({{\varvec{\beta}}}_{{\varvec{a}}}^{1},\boldsymbol{ }{\boldsymbol{ }{\varvec{r}}}_{{\varvec{a}}}^{1}\) and \({{\varvec{\eta}}}_{{\varvec{a}}}^{1}\), such that when \(0<{\varvec{\beta}}<{{\varvec{\beta}}}_{{\varvec{a}}}^{1}\) and \({{\varvec{r}}}_{{\varvec{a}}}^{1}<{\varvec{r}}<\frac{1}{2}\) and \({\varvec{\beta}}<{\varvec{\eta}}\le {{\varvec{\eta}}}_{{\varvec{a}}}^{1}\), the sales quantity of the manufacturer channel under asymmetric channel substation is lower than in case E, \({{\varvec{q}}}_{2{\varvec{a}}}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}\le {{\varvec{q}}}_{2}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}.\) Otherwise, \({{\varvec{q}}}_{2{\varvec{a}}}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}>{{\varvec{q}}}_{2}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}\).

-

(ii)

The equilibrium wholesale price under asymmetric channel substitution is always lower than in case E, \({{\varvec{w}}}_{{\varvec{a}}}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}>{{\varvec{w}}}^{{\varvec{E}}\boldsymbol{*}}\).

-

(iii)

The manufacturer’s profit under asymmetric channel substitution is always lower than in case E, \({\pi }_{Ma}^{E*}<{\pi }_{M}^{E*}.\)

Firstly, overall sales are lower under asymmetric channel substitution. When the retailer substitutes more for the manufacturer’s agency channel over the platform’s reselling channel, it leads to inefficient channel utilization. This imbalance reduces total sales as the manufacturer is forced to cut back on agency sales to avoid market saturation and price conflicts. High substitution ability or commission costs intensify competition, prompting the manufacturer to reduce agency channel sales to balance demand across channels. Conversely, if the substitution ability is weaker but the commission rate is high, agency sales still drop to control costs.

Secondly, the wholesale price is always lower under asymmetric substitution. With the retailer substituting more through the manufacturer’s agency channel, the manufacturer faces pressure to keep the retailer engaged while also maintaining demand through other channels. By lowering the wholesale price, the manufacturer encourages continued use of the platform and retail channels to balance competition, leading to a lower equilibrium wholesale price compared to the symmetric substitution scenario.

Thirdly, the manufacturer’s profit is always lower under asymmetric substitution. With asymmetric substitution, the manufacturer cannot leverage its agency channel as effectively because the retailer’s increased substitution doesn’t fully compensate for the competitive losses from other channels. The downward pressure on the wholesale price, combined with decreased sales volumes, forced the manufacturer to reduce both sales quantity and prices, leading to diminished profit and market position.

Proposition 9

In the scenario of asymmetric channel substitution, a Pareto improvement region persists, determined by the commission rate and channel substitutability, resulting in enhanced profits for all supply chain members. However, the Pareto region gradually diminishes as \(\eta\) increases.

Proposition 9 demonstrates that despite the higher substitutability of the retail channel for the manufacturer’s agency channel, the manufacturer can benefit from encroachment. Even in highly competitive environments, where the retail channel acts as a strong substitute for the manufacturer’s agency channel, the manufacturer can still realize profit gains by leveraging its control over pricing. This underscores the importance of pricing strategies in multichannel environments, where effective control over one’s channel can offset competitive pressures from other channels. Despite intensified competition, manufacturer agency channel encroachment creates a Pareto improvement region where, under optimal commission rates and channel substitution rates, profits increase for all entities involved. Businesses must carefully consider commission rate and channel substitution effects to maintain a Pareto improvement region, ensuring all supply chain members benefit. By optimizing these factors, companies can enhance overall supply chain profitability.

Figure 6 illustrates these dynamics across different values of \(\eta\), where \(\eta =1.5\beta , \eta = 5\beta\) and \(\eta =10\beta\). Region A represents the Pareto region, constrained by both values not exceeding 1. The size of the Pareto improvement region is heavily influenced by the relative substitution rates \(\eta\) and \(\beta\). As \(\eta\) increases relative to \(\beta\), the Pareto region shrinks due to the increasing advantage of the platform reselling channel, which weakens the retailer’s profit potential. Since the retailer’s profit improvement condition defines the boundary of the Pareto region, this effect leads to a smaller space where all parties can benefit, emphasizing the critical role that competitive balance between channels plays in sustaining supply chain profitability. Regions A and C denote profit improvements for the platform, while regions A and B denote profit improvements for the retailer. This underscores the importance of balancing cooperation and competition among supply chain members in multi-channel market environments to sustain market stability and foster growth.

Conclusions and future research directions

This study examines the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment decision and its impact when it has already operated a platform reselling channel and a retailer channel on the platform. Firstly, the analysis indicates that the stability of the channel structure exists only when the platform’s commission rate is relatively low, or when it is high but the retailer’s substitution ability is relatively weak. Secondly, the manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment triggers a competition effect, leading to a reduction in market demand for both the platform’s reselling channel and the retailer’s channel as a larger share of the market shifts toward the manufacturer’s agency channel. For the platform, although sales in its reselling channel decline, the commission revenue effect brought by the manufacturer’s agency channel compensates for this loss, allowing for the potential increase in the platform’s overall revenue. Compared to the platform, the retailer is in a more challenging position. The manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment directly impacts the retailer’s market share and profits, as consumers increasingly prefer purchasing through the agency channel, thereby weakening the retailer’s sales and profitability. To compensate for the losses in sales experienced by the platform and retailer, the manufacturer lowers the wholesale price in equilibrium. This reduced wholesale price improves the total market sales despite the decrease in the combined sales of the platform and retailer. However, market demand is redistributed among the channels, further strengthening the manufacturer’s market position. Under equilibrium decisions, the manufacturer always benefits from agency channel encroachment, and a Pareto improvement region exists, allowing all supply chain participants to improve their profits.

This research extends the model to explore the effects of sequential decision-making and asymmetric channel substitution on game equilibrium. Compared to simultaneous decision-making, the manufacturer always reduces the sales volume of the agency channel products under sequential decision-making and lowers the wholesale price when the retailer’s substitution ability is strong. This indicates that the manufacturer focuses more on the competition effects of channel encroachment under sequential decision-making. However, such adjustments in the manufacturer’s decisions only result in higher profits for the manufacturer when the retailer’s substitution ability is strong. At the same time, the retailer’s profits are further compressed under sequential decision-making, as reflected by the shrinking of the Pareto improvement region. In contrast to the symmetric channel substitution scenario, the manufacturer faces greater competitive pressure from the retailer under asymmetric channel substitution. Although the manufacturer increases the wholesale price and adjusts sales across channels according to the competitive situation, its profits are always lower than in the symmetric substitution case.

The conclusions of this study offer significant managerial insights, particularly in the context of multi-channel retail environments where the manufacturer’s platform reselling and retailer channels coexist. A real-world example can be seen in the dynamics of e-commerce giants like Amazon or JD.com. In these platforms, the manufacturers often establish their own direct sales channel (agency channel) while competing against the platform’s reselling model and third-party retailers. The study reveals that manufacturers must carefully consider the competitive effects of agency channel encroachment. Our results show that where the retailer’s substitution ability is strong, manufacturers can benefit from lowering wholesale prices and reducing agency sales volumes to avoid over-saturating the market and diminishing overall channel efficiency. Platforms should strategically set commission rates; lower rates may attract more manufacturers to encroach, thereby increasing commission revenue. However, caution is needed to prevent excessive channel expansion and conflicts stemming from overly low commissions. Retailers must recognize the dual effects of profitability from commission rates and channel substitution capabilities. Managers should prioritize the Pareto improvement region, aiming for strategies and measures that balance profitability and mitigate conflicts, thereby promoting overall supply chain improvement.

Despite these contributions, this study has limitations. We treated channel sales quantities as decision variables without considering consumer preferences for different channels and their channel selection behaviors. Future research could explore these aspects to deepen insights into how channel attributes—such as convenience, price, and service quality—affect consumer choices and channel profitability. Additionally, investigating how platforms’ superior access to market data and enhanced marketing capabilities affect manufacturers’ strategic decisions, including channel selection, product positioning, and competitive responses, would provide valuable insights into shaping industry standards and driving supply chain efficiencies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Marketplace Pulse. (2023). Year in review 2023. Retrieved from https://www.marketplacepulse.com/year-in-review-2023#ecommerce (accessed Jun 14, 2024).

JD.com, Inc. (2023). Annual report 2023. Retrieved from https://ir.jd.com/static-files/8d40e85a-72ec-4796-8bbc-eb5edd09c78a (accessed Jun 14, 2024).

Arya, A., Mittendorf, B. & Sappington, D. E. M. The bright side of supplier encroachment. Market. Sci. 26(5), 651–659. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1070.0280 (2007).

Huang, S., Guan, X. & Chen, Y.-J. Retailer information sharing with supplier encroachment. Prod. Oper. Manag. 27(6), 1133–1147. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12860 (2018).

Cattani, K., Gilland, W., Heese, H. S. & Swaminathan, J. Boiling frogs: Pricing strategies for a manufacturer adding a direct channel that competes with the traditional channel. Prod. Oper. Manag. 15(1), 40–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.2006.tb00002.x (2006).

Tsay, A. A. & Agrawal, N. Channel conflict and coordination in the E-commerce age. Prod. Oper. Manag. 13(1), 93–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.2004.tb00147.x (2004).

Abhishek, V., Jerath, K. & Zhang, Z. J. Agency selling or reselling? Channel structures in electronic retailing. Manag. Sci. 62(8), 2259–2280. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2230 (2016).

Hagiu, A. & Wright, J. Marketplace or reseller?. Manag. Sci. 61(1), 184–203. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.2042 (2015).

Jerath, K. & Zhang, Z. J. Store within a store. J. Market. Res. 47(4), 748–763. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.47.4.748 (2010).

Kwark, Y., Chen, J. & Raghunathan, S. Platform or wholesale? A strategic tool for online retailers to benefit from third-party information. Mis Q. 41(3), 763-A17 (2017).

Chen, L., Nan, G. & Li, M. Wholesale pricing or agency pricing on online retail platforms: The effects of customer loyalty. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 22(4), 576–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/10864415.2018.1485086 (2018).

Zennyo, Y. Strategic contracting and hybrid use of agency and wholesale contracts in e-commerce platforms. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 281(1), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2019.08.026 (2020).

Tian, L., Vakharia, A. J., Tan, Y. R. & Xu, Y. Marketplace, reseller, or hybrid: strategic analysis of an emerging E-commerce model. Prod. Oper. Manag. 27(8), 1595–1610. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12885 (2018).

Wei, Y. & Dong, Y. Product distribution strategy in response to the platform retailer’s marketplace introduction. Eur. J. Oper. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2022.03.021 (2022).

Mantin, B., Krishnan, H. & Dhar, T. The strategic role of third-party marketplaces in retailing. Prod. Oper. Manag. 23(11), 1937–1949. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12203 (2014).

Liu, B., Guo, X., Yu, Y. & Tian, L. Manufacturer’s contract choice facing competing downstream online retail platforms. Int. J. Prod. Res. 59(10), 3017–3041. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1744767 (2020).

Song, W., Chen, J. & Li, W. Spillover effect of consumer awareness on third parties’ selling strategies and retailers’ platform openness. Inf. Syst. Res. 32(1), 172–193. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2020.0952 (2021).

Ha, A. Y., Tong, S. & Wang, Y. Channel structures of online retail platforms. Manuf. Ser. Oper. Manag. 24(3), 1547–1561. https://doi.org/10.1287/msom.2021.1011 (2022).

Li, G., Tian, L. & Zheng, H. Information sharing in an online marketplace with co-opetitive sellers. Prod. Oper. Manag. 30(10), 3713–3734. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.13460 (2021).

Balasubramanian, S. Mail versus mall: a strategic analysis of competition between direct marketers and conventional retailers. Market. Sci. 17(3), 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.17.3.181 (1998).

Ferrer, G. & Swaminathan, J. M. Managing new and differentiated remanufactured products. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 203(2), 370–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2009.08.007 (2010).

Chiang, W. Y., Chhajed, D. & Hess, J. D. Direct marketing, indirect profits: A strategic analysis of dual-channel supply-chain design. Manag. Sci. 49(1), 1–20 (2003).

Cai, G. Channel selection and coordination in dual-channel supply chains. J. Retail. 86(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2009.11.002 (2010).

Cai, G., Dai, Y. & Zhou, S. X. Exclusive channels and revenue sharing in a complementary goods market. Market. Sci. 31(1), 172–187. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1110.0688 (2012).

Shen, Y., Willems, S. P. & Dai, Y. Channel selection and contracting in the presence of a retail platform. Prod. Oper. Manag. 28(5), 1173–1185. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12977 (2019).

Chen, C., Zhuo, X. & Li, Y. Online channel introduction under contract negotiation: Reselling versus agency selling. Manag. Decis. Econ. 43(1), 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.3364 (2022).

Yan, Y., Zhao, R. & Liu, Z. Strategic introduction of the marketplace channel under spillovers from online to offline sales. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 267(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2017.11.011 (2018).

Ryan, J. K., Sun, D. & Zhao, X. Competition and coordination in online marketplaces. Prod. Oper. Manag. 21(6), 997–1014. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.2012.01332.x (2012).

Wang, L., Chen, J., & Song, H. Marketplace or reseller? Platform strategy in the presence of customer returns. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev, 153, 102452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2021.102452 (2021).

Yi, Z., Wang, Y., Liu, Y. & Chen, Y.-J. The impact of consumer fairness seeking on distribution channel selection: direct selling vs. agent selling. Prod. Oper. Manag. 27(6), 1148–1167. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12861 (2018).

Pu, X., Sun, S. & Shao, J. Direct selling, reselling, or agency selling? manufacturer’s online distribution strategies and their impact. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 24(2), 232–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/10864415.2020.1715530 (2020).

Zhen, X., Xu, S., Li, Y. & Shi, D. When and how should a retailer use third-party platform channels? The Impact of spillover effects. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 301(2), 624–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2021.11.008 (2022).

Ha, A. Y., Luo, H. & Shang, W. Supplier encroachment, information sharing, and channel structure in online retail platforms. Prod. Oper. Manag. 31(3), 1235–1251. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.13607 (2021).

Luo, H., Zhong, L. & Nie, J. Quality and distribution channel selection on a hybrid platform. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 163, 102750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2022.102750 (2022).

Zhang, T., Tang, Z. & Han, Z. Optimal online channel structure for multinational firms considering live streaming shopping. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2022.101198 (2022).

Chen, X., Wang, X. & Xia, Y. Production coopetition strategies for competing manufacturers that produce partially substitutable products. Prod. Oper. Manag. 28(6), 1446–1464. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12998 (2019).

Chen, Y.-J., Shum, S. & Xiao, W. Should an OEM retain component procurement when the CM produces competing products?. Prod. Oper. Manag. 21(5), 907–922. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.2012.01325.x (2012).

Wang, Y., Niu, B. & Guo, P. On the advantage of quantity leadership when outsourcing production to a competitive contract manufacturer. Prod. Oper. Manage. 22(1), 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.2012.01336.x (2013).

Qin, X., Liu, Z. & Tian, L. The strategic analysis of logistics service sharing in an e-commerce platform. Omega 92, 102153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2019.102153 (2020).

He, P., He, Y., Tang, X., Ma, S. & Xu, H. Channel encroachment and logistics integration strategies in an e-commerce platform service supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 244, 108368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108368 (2022).

Sun, L., Lyu, G., Yu, Y. & Teo, C. P. Cross-border e-commerce data set: Choosing the right fulfillment option. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 23(5), 1297–1313. https://doi.org/10.1287/msom.2020.0887 (2021).

Ha, A. Y., Tian, Q. & Tong, S. Information sharing in competing supply chains with production cost reduction. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 19(2), 246–262. https://doi.org/10.1287/msom.2016.0607 (2017).

Zhang, S. & Zhang, J. Agency selling or reselling: E-tailer information sharing with supplier offline entry. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 280(1), 134–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2019.07.003 (2020).

Tan, Y., Carrillo, J. E. & Cheng, H. K. The agency model for digital goods. Decis. Sci. 47(4), 628–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12173 (2016).

Zhang, J., Cao, Q. & He, X. Contract and product quality in platform selling. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 272(3), 928–944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2018.07.023 (2019).

Singh, N. & Vives, X. Price and quantity competition in a differentiated duopoly. Rand J. Econ. 15(4), 546–554 (1984).

Li, Z., Gilbert, S. M. & Lai, G. Supplier encroachment under asymmetric information. Manag. Sci. 60(2), 449–462. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2013.1780 (2014).

Li, Z., Gilbert, S. M. & Lai, G. Supplier encroachment as an enhancement or a hindrance to nonlinear pricing. Prod. Oper. Manag. 24(1), 89–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12210 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G. and S.Y.; methodology M.G. and Y.L.; software, M.G. and Y.L.; validation, S.Y. and C.S.; formal analysis, S.Y. and C.S; investigation, M.G. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, all authors participated; supervision, S.Y. and C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, M., Yang, S., Shi, C. et al. Manufacturer’s agency channel encroachment on an online retail platform. Sci Rep 14, 29037 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79834-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79834-w