Abstract

In patients with HIV-diabetes mellitus (DM) comorbidity, invasive blood glucose testing can increase the risk of HIV-related blood contamination and discourage regular glucose monitoring. Digital continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems may allow real-time glucose monitoring without the need for blood specimens. However, in high-burden HIV-DM countries, current glucose monitoring practices and their challenges are insufficiently explored to guide digital CGM research and developments. This study sought to explore the lived experiences of patients with HIV-DM comorbidity and their healthcare providers regarding glucose monitoring practices, and their openness to CGM and other digital technologies, to provide formative insights for a planned implementation trial of digital CGM in Ethiopia. A phenomenological qualitative study was conducted among patients with HIV-DM and their providers at the two largest public hospitals in Ethiopia. Both groups were interviewed face-to-face about DM clinic workflows, blood glucose monitoring and self-testing practices, and potential benefits and limitations of digital CGM systems. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed thematically. A total of 37 participants were interviewed, consisting of 18 patients with HIV-DM comorbidity and 19 healthcare providers. Patients had an average (min-max) duration of living with HIV and DM of 14 (8–31) and 6.6 (1–16) years, respectively, with 61% taking insulin—33% alone and 28% alongside oral hypoglycemic agents—and 79% having comorbid hypertension. The thematic analysis identified five main themes: “Diabetes routine clinical care and follow-up”, “Blood glucose monitoring practices”, “Perceptions about digital CGMs”, “Technology adoption”, and “Financial coverage”. Home self-testing was deemed beneficial, but the need for regular follow-ups, result cross-referencing, and glucometer reliability were emphasized. Patients performed fingerstick themselves or with family members, expressing concerns about waste disposal and the risk of HIV transmission. They rely mainly on health insurance for DM care. Patients and providers are happy with the quality of DM services but note a lack of integrated HIV-DM care. Very few providers and patients possessed background information about digital CGMs, and all have not yet utilized them in practice, but expressed keen interest in trying them, representing an important step for upcoming CGM clinical trials in these settings. Given the crucial role of regular glucose testing in managing HIV-DM comorbidity, it is essential to explore testing options that align with patient preferences and minimize the risk of HIV transmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

HIV-diabetes mellitus (HIV-DM) comorbidity presents a significant health challenge, particularly in countries with a high HIV prevalence1,2. Current standard-of-care practices for managing diabetes often involve invasive blood pricking techniques. These methods include self-testing with capillary blood glucometers, point-of-care testing devices for capillary or venous glucose at health facilities, and analyzers for venous blood glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels. Unfortunately, the painful and invasive nature of these procedures leads to two-thirds of patients with DM avoiding regular monitoring of their glycemic levels due to tissue damage caused by repeated blood collection3,4. For patients with HIV-DM comorbidity, household members may be at risk of HIV transmission as patients often involve family members in glucose testing, during fingerstick, testing, or disposal, when they are unable to perform these tasks themselves or are unwell.

In recent years, new digital continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems have emerged to enhance glycemic control and monitor treatment outcomes with minimally invasive procedures. The systems are based on the principle of optical (photoacoustic detection), electromagnetic (nanomaterial-based sensing and electromagnetic sensing), or acoustic (spectroscopy) methods5,6. Real-time CGM (rtCGM) devices, such as the Freestyle Libre 2 flash rtCGM (Abbot Laboratories, Alpharetta, Georgia, US)7 and the Dexcom G6 rtCGM (Dexcom, Inc., San Diego, CA, US)8 have notably gained prominence. These devices enable patients to monitor their glucose levels without needing fingerstick or blood specimens. The devices are equipped with a small electrode sensor that is inserted into the skin of the patient’s arm to measure glucose in the interstitial space, and continuously read glucose levels in real-time and provide alerts for hyper- or hypoglycemia anytime and anywhere. Additionally, they feature systems for directly sharing results with clinicians and linking results to smartphone applications7,8. Current developments in digital health for DM extend beyond CGM, which include support for healthy nutrition and weight control, guidance on medication dosing, patient training, maintenance of lifestyle modifications, and ultimately, reducing disease complications9. However, limited randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohorts, and case-control studies have been conducted to inform the benefits, challenges, and recommendations concerning diabetes digital App technologies10.

In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where three-fourths of people with DM reside and access to management and care is limited11, there is an urgent need for evidence on how these individuals can benefit from emerging diabetes technologies such as CGM. This is especially crucial in countries such as Ethiopia that have demonstrated a commitment to the digitalization of their health care systems. In Ethiopia, approximately 2 million people aged 20 to 79 live with DM, having an estimated annual mortality of 26,44812. The country has a high number of people with pre-diabetes, including impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose, indicating a future rise in diabetes cases that the country’s health system must prepare for. The country’s diabetes healthcare expenditure remains among the lowest, affecting access and quality of diabetes care and management. Similarly, in Ethiopia, 610,000 people have been diagnosed with HIV, 480,264 (78%) were on antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 12,000 died due to HIV in 202113. Facility and population-based studies reveal varying rates of diabetes prevalence among people living with HIV (PWH), ranging from 7.1 to 80.6%14,15,16,17. However, innovative models that integrate diabetes care into HIV clinics are lacking. Digital health solutions hold promise in the country18,19,20,21, and national efforts are underway to implement this technology effectively22,23.

Qualitative studies from African and developed countries reveal that while DM patients and healthcare providers generally find CGM acceptable and appropriate, they express concerns regarding health education, financial burdens, limited services, device improvements, consumer support, insurance coverage, device accuracy and reliability, and challenges related to device insertion, adhesion, and removal24,25,26,27,28. Although such studies from Ethiopia have not been documented, qualitative researches on patients with HIV-DM comorbidity in the country highlight several barriers at the individual, healthcare, and community levels that hinder their access to diabetes care, including a lack of integrated services, long waiting times, costs, and experiences of stigma and discrimination29,30. Negligent and irregular blood glucose testing, limited access to home blood glucose monitors, and infrequent diabetes follow-up visits at healthcare facilities are significantly associated with poor glycemic control in the country31,32,33.

Therefore, this study aimed to explore the lived experiences of patients with HIV-DM comorbidity and their healthcare providers regarding glucose monitoring practices, and their openness to CGM and other digital technologies, to provide formative insights for a planned implementation trial of digital CGM in Ethiopia.

Methods

Design

This was a qualitative phenomenological, facility-based study. The study adhered to the COREQ (COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative studies) guidelines. The analysis was guided by key exploratory research questions arising from the WHO’s digital health implementation considerations, addressing areas such as services and applications, standards and interoperability, workforce, and infrastructure34. The exploratory research questions included:

-

What glucose monitoring methods are currently used, and how do patients and healthcare providers perceive the effectiveness and reliability of the methods?

-

What are patients’ experiences and feelings about fingerstick and glucose self-testing?

-

How do patients and providers perceive digital CGM systems?

-

How is healthcare services delivered to patients with HIV-DM comorbidity, and how can this care be integrated with CGM systems?

Setting

The study took place in Ethiopia, which has 523 public hospitals. Among these hospitals, five operate at the national level under federal government leadership, while the remaining 518 public hospitals provide services at the regional or zonal level, overseen by Regional Health Bureaus. From the five federal hospitals, two were purposively selected for this study due to their significant role as primary facilities for HIV and diabetes care, serving larger populations that come from all corners of the country. These selected hospitals are Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital and St. Paul’s Referral Teaching Hospital.

Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital stands as Ethiopia’s largest tertiary-level specialized and teaching hospital. It operates as a public teaching hospital affiliated with the Addis Ababa University College of Health Sciences, comprising four multitiered Schools. With a workforce of approximately 1,245 clinical and 1,200 administrative staff, the hospital hosts over 20 departments, offering a wide range of medical, surgical, obstetrics and gynecology, radiology and imaging, clinical laboratory, and pharmacy services35,36. The hospital houses two separate HIV clinics for adults and children, where over 4,000 PWH receive ART. The hospital operates a diabetes clinic, serving close to 1,000 diabetes patients on an outpatient basis each month.

St. Paul’s Referral Teaching Hospital ranks as the second largest tertiary-level referral teaching hospital in Ethiopia. It serves approximately 1,200 clients daily and employs around 3,000 clinical, academic, and administrative staff who offer specialized medical services to patients referred from across Ethiopia37. The hospital holds 13 departments providing comprehensive clinical care and treatment. It has separate dedicated clinics for diabetes and HIV, with the HIV clinic alone providing ART services to over 5,080 PWH38.

Participants

This study was based on the lived experiences of patients with HIV-DM comorbidity and their healthcare providers. Within the broader population of patients with DM, the study specifically targeted those with HIV-DM comorbidity for their heightened risk of in-house blood contamination during self-testing, which carries a risk of HIV transmission among family members and increases the burden of fingerstick procedures among patients.

Patient participant recruitment

The study’s patient population included adults aged ≥ 18 years with HIV-DM comorbidity who were receiving diabetes care at the diabetes clinics within the two study hospitals. To be eligible for participation, a patient needed to have HIV-DM comorbidity, possess a formal diabetes identification (ID) number registered in the electronic health records (EHR) of the diabetes clinics, attend the diabetes clinic at the time of data collection, and demonstrate the ability and willingness to provide informed consent. “Attending the diabetes clinic” was defined as having visited the DM clinic within the last six months for either a diabetes medication refill or clinical follow-up. The participants were recruited using the EMR database in each facility as the sample frame. In each diabetes clinic, the EMR data were reviewed, and individuals with HIV-diabetes comorbidity were identified using purposive sampling. Among these, those who had visited the facility recently within the last six months were identified by the study team, and their upcoming follow-up visit or medication refill appointment dates were recorded. Those with very recent follow-up visits were selected for interviews, targeting a prespecified sample size of 20 patients—10 from each study site—to achieve thematic saturation.

Healthcare provider participant recruitment

The healthcare providers involved in this study included medical doctors, nurses, and medical laboratory technologists directly involved in the diagnosis, care, and treatment of patients with HIV-DM comorbidity. To be eligible, these participants were required to be full-time staff members at the study hospitals, primarily engaged in providing diabetes and HIV services for a minimum of three months to ensure a good understanding of patients with HIV-DM comorbidity and demonstrate the ability and willingness to provide informed consent. Using purposive sampling, providers who met all required criteria were selected from the study sites, with a targeted sample size of 20 providers—10 from each study site—prespecified to achieve thematic saturation.

Recruitment stopped upon reaching thematic saturation, indicating a full understanding of the participants’ perspectives during the interviews, with no new data emerging, The planned maximum was set at 40 total participants, including both patients and providers.

Face-to-face interviews

Interview guides for both participant groups were developed in line with the objectives of the study and following reviews of existing literature. The interview guides, initially developed in English, were translated into Amharic, the national language of Ethiopia and the language used for formal communication in the study settings. Consequently, the interviews were conducted in Amharic. Trained study staff conducted face-to-face interviews using open-ended guides, with each session lasting between 45 and 60 min. Reflexivity was integrated throughout the study process to encourage the investigators’ self-reflection and peer debriefing on personal assumptions or experiences that could impact data collection and analysis. The socio-demographic characteristics of the patients and providers were also recorded. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Patient participants were interviewed during their regular appointment dates at the diabetes clinics, with a first-come first-served approach, in a separate quiet room once they had completed their follow-up visit. The interview guide covered various topics, including the participants’ history of receiving care at the diabetes clinic, any integrated HIV-diabetes services they received, whether they had ever missed routine diabetes appointments and reasons for doing so, the workflow during their follow-up visits, the glucose testing mechanisms they used to monitor their glucose levels regularly, the benefits and challenges associated with current glucose monitoring practices, their views on self-testing blood glucose levels using glucometers, their experiences and feelings regarding fingerstick, how their diabetes diagnosis and treatment costs were covered, their knowledge about digital CGM systems, their opinions on the feasibility of such devices being introduced, and their evaluation of their capacity to handle electronic devices.

Provider participants were interviewed at a mutually convenient time and location. The interview focused on several key areas, including their role in managing patients with HIV-DM comorbidity, the current workflow and management systems for diabetes care, any specialized services or integrated HIV-DM models of care provided, the glucose testing methods employed for regular monitoring of diabetic patients, the advantages and challenges associated with current glucose monitoring practices for patients with HIV-diabetes comorbidity, their perspectives on patients self-testing their blood glucose levels using personal glucometers, their familiarity with digital glucose monitoring devices, and their opinions on the feasibility of implementing such devices, both for patients and in terms of integration with the current EMR system.

Interview measures

The interview guide included 16 questions for both patient and provider participants, organized into four key domains. The questions addressed the following topics:

-

What glucose testing mechanisms are currently utilized to regularly monitor glucose levels of patients with DM?

-

How do patients and their providers perceive self-testing blood glucose levels using patients’ own glucometer?

-

What are the benefits and challenges of the current standard of care glucose monitoring practices, and how trustworthy are blood glucose results obtained from glucometer self-testing and facility laboratories?

-

What are patients’ experiences and feelings about fingerstick?

-

What is the workflow in DM clinics for the management of patients with DM in their regular follow-up?

-

What special services or HIV-DM integrated models of care exist for patients with HIV-diabetes comorbidity? Are they getting the services separately for the two diseases or at a time as integrated care?

-

Do patients ever miss their routine diabetes appointments? If so, why?

-

How are the costs for diabetes diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up covered?

-

Are patients and their providers aware of digital glucose monitoring systems?

-

How do patients and clinicians perceive digital CGMs as they learn about them from study staff?

-

How do patients and providers view the feasibility of digital CGM being brought to them? Do they think they will be able to adapt and handle them with optimum training and guidance?

-

How do healthcare providers evaluate the current EHR systems in the hospital to link with and support the digital CGM?

-

How do patients and providers evaluate their capacity to handle such new digital systems, including their prior experience using glucometers, smartphones for health and lifestyle monitoring, or laptops or desktop computers?

-

Do patients and providers believe that technology in general makes their lives easier or more difficult?

The exploratory questions included the operational aspects of diabetes management, exploring how diabetes clinic workflows, HIV-DM integrated care, appointment, and the costs of care and diagnosis are handled. The goal was to gain insights from participants’ lived experiences regarding these operational factors and to investigate their potential direct and indirect impacts on the implementation of CGM systems. Additionally, demographic information was collected from participants during the interview.

Data analysis

The verbatim transcripts were produced involving the translation of transcripts from the local (Amharic) language into English and read by the research team. The translated transcripts were then thoroughly read to facilitate familiarity and initial theme through phenomenological method. Each interview translation was structured by interview question and response, with open coding applied to each. Initial coding was performed by TM, MJ, and study staff members, with a subset of interviews independently coded by a second researcher to ensure result validity. The research team reviewed and revised the coding, resolving discrepancies through group discussions. Once saturation was achieved, codes were organized into distinct themes. One team assigned meaningful text to the identified domains, while another ensured the codes aligned with those domains. The teams then narrowed down the translations to segments relevant to the study objectives and reached consensus on the selected quotes. Participant quotations were presented in tables to illustrate each theme. The sociodemographic characteristics of participants were analyzed descriptively.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval

has been granted by the Institutional Review Board of the College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia, and the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of St. Paul’s Hospital Millenium Medical College, Ethiopia. Following the IRB approvals, permission has been obtained from the study sites to commence the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The study adhered to the principles of trustworthiness in qualitative research to ensure credibility, transferability, conformability, and dependability. Direct and indirect identifiers were minimized during data collection and replaced with codes, and the collected audio and written data were protected against unauthorized access. Potential study participants were provided with a comprehensive study information sheet and were required to sign a consent form. All documentation leaving the study sites was anonymized.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

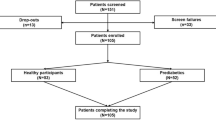

We interviewed a total of 37 participants, consisting of 18 patients with HIV-DM comorbidity and 19 healthcare professionals responsible for providing diabetes care and treatment to PWH. The mean ages of the patients and providers were 54.2 and 34.9, respectively, with age ranges spanning from 42 to 71 for patients and 26 to 50 for clinicians. Patients had an average duration of living with HIV of 14 years (ranging from 8 to 31 years) and with DM of 6.6 years (ranging from 1 to 16 years). Among them, 61% were on insulin therapy—33% using it alone and 28% in combination with oral hypoglycemic agents. Additionally, 79% of the patients had comorbid hypertension. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of study participants.

Study themes

The thematic analysis generated five primary themes with 16 subthemes. These main themes included “Diabetes routine clinical care and follow-up”, “Blood glucose monitoring practices”, “Perceptions about digital CGMs”, “Technology adoption”, and “Financial coverage”. Figure 1 illustrates the themes and sub-themes.

Theme 1: diabetes routine clinical care and follow-up

Theme 1 focused on the regular clinical care and ongoing monitoring of diabetes, leading to the identification of four subthemes: workflow, patient engagement, patient satisfaction with clinical care, and DM-HIV integrated care. Table 2 illustrates some of the major quotes highlighting what participants emphasized in each subtheme under this theme.

According to the interviewees, DM clinics adhere to a first-come, first-served system. The procedural flow involves providing health education, collecting patient cards, recording vital signs, assigning patients to physicians, reviewing glucose and other lab results, conducting essential examinations and treatments, and setting up the next appointment. Clinicians order laboratory tests, which patients need to received and bring with the test results to their next appointment. New patients undergo initial investigations, and subsequent appointments are tailored to their clinical requirements. Most patients have been under diabetes care in hospitals for an average of around six years. They maintained a regular visit schedule, usually every three months, although clinic appointments may be adjusted based on their health condition. Clinicians emphasized the importance of health education in patient care, focusing on diabetes management. The clinics offer education sessions thrice weekly on medication, injections, nutrition, exercise, and glucose control.

The patients underscored their dedication to attending appointments consistently, demonstrating a strong sense of engagement regarding their diabetes care. They adhered to scheduled follow-up visits and recognize the significance of regular monitoring and medication adjustments. However, it is worth noting that according to clinicians, some patients, especially those facing transportation obstacles or significant social obligations (e.g., social determinants of health), may occasionally miss follow-up appointments or visit another nearby health center. The patients expressed satisfaction with the level and quality of care provided, including their interactions with nurses, doctors, and pharmacy staff. However, they did acknowledge occasional challenges, such as longer appointment times, prolonged wait times arising from high patient volume, limited availability of diabetes medications, and obstacles in accessing specialists in the field.

Both patients and clinicians highlighted the lack of integrated services for patients with HIV-DM comorbidity. Patients care journey involve managing diabetes and HIV separately, requiring separate appointments at different clinics-DM clinic and ART clinic. Patients expressed dissatisfaction with this gap. The patients perceived the integrated appointments as beneficial in terms of time-saving and convenience. Clinicians acknowledged that patients with HIV-DM comorbidity were managed alongside other patients with either comorbidity, with similar appointment scheduling and clinical workflows, as there was no dedicated clinic for patients with HIV-DM comorbidity.

Theme 2: blood glucose monitoring practices

Theme two illustrates the systems and practices utilized for monitoring blood glucose levels, resulting in six subthemes: devices and techniques, patient self-testing, fingerstick, results reliability, and access to supplies. Table 3 consolidates the major quotes provided by study participants for each subtheme.

The glucose monitoring technique primarily revolves around Fasting Blood Sugar (FBS) and HbA1c tests. FBS entails a combination of self-testing at home using glucometers and laboratory-based testing either within or outside the hospital setting. As per interviews with medical laboratory technologists, the hospital laboratories are equipped with automated COBAS and/or Beckman Coulter clinical chemistry analyzers for FBS and related testing. Patients who provide blood samples during clinical visits can expect results to be available the following day, which puts an additional burden on both the patients and clinicians. Runners, tasked with maintaining log books of sample collections, retrieve these results from the laboratory and input them into the patient charts for review by clinicians. To help complete the visit on the same day, patients were encouraged to undergo FBS testing either through self-testing at home or in laboratories prior to their visits and to bring the results with them. In emergency situations involving hypoglycemic patients, nurses conduct random blood sugar (RBS) testing in the clinic or at the triage using point-of-care glucometers available on-site, avoiding the need to send patients to the laboratory.

Patient self-testing at home was widely recognized as advantageous. Clinicians recognized that self-monitoring of glucose levels empowers patients to manage hypo/hyperglycemia, seek timely medical assistance, and provide valuable data. According to the clinicians, some patients preferred self-monitoring of their blood glucose levels and present their records during follow-up appointments. These patients exhibit disciplined adherence to treatment and take proactive measures to manage their condition. Patient interviewees also found self-testing helpful for adjusting their diet and lifestyle based on blood glucose levels, enhancing awareness and management of their health. However, both clinicians and patients emphasized the importance of providing proper guidance on glucometer handling and suggested cross-referencing results with laboratory results or HbA1c to ensure accuracy. They also cautioned against glucometer malfunction. While generally trusting the results, patients acknowledged occasions where doctors could request repeat tests, indicating some skepticism in certain situations. Clinicians, in general, note that a considerable number of patients do not have a glucometer at home, though they are interested in having one, but often check their glucose levels at nearby health facilities or pharmacies, beyond their routine clinic visits. They typically record these results in a notebook provided by healthcare professionals.

Clinicians note that patient experiences with finger pricking can differ, with pediatric patients and their families often reporting more discomfort. However, patients typically recognize the importance of finger-stick blood sampling for their health and are willing to tolerate the procedure despite some initial discomfort. Over time, patients tend to become more accustomed to the process. Clinicians trust the reliability of test results obtained from the clinic’s laboratory and self-testing but may verify results against clinical findings and prompt retesting if doubts arise. While they generally trust lab accuracy, they recognize the importance of clinical assessment for validation. Laboratory technologists also express confidence in their results, emphasizing calibration and quality control measures. They stress the importance of maintaining standards through internal quality control, external assessments, and rigorous verification processes for equipment and reagents. Similarly, patients trust both self-testing devices and laboratory results, especially when their own feelings align with measurements. However, they acknowledge instances where clinicians may request repeat tests, indicating some skepticism in certain situations. In addition, stockouts and interruptions in the supply chain, notably of glucometer test strips for patient self-testing and reagents and calibration standards in hospital laboratories, pose challenges to the glucose monitoring system. Clinicians note that supply interruptions and equipment malfunctions in the laboratory may necessitate patients’ referrals to external laboratory facilities for testing.

Theme 3: perceptions about digital continuous glucose monitoring device

Theme three explores the perceptions of patients and clinicians regarding digital CGMs, yielding three subthemes: acceptability, prerequisites, and integration into facility EHR systems. Table 4 consolidates the key quotes provided by study participants in each subtheme.

All patients, except one, were unfamiliar with digital CGMs and relied on study interviewers’ information when providing feedback about CGMs. They warmly welcomed the opportunity to learn about them and expressed enthusiastic interest in trying them at home. They believed that digital CGMs would offer practical and benefits if introduced, referring to advantages such as real-time monitoring, user-friendliness, elimination of blood samples, reduced discomfort from frequent testing, integration with cellphone applications, and potential stress alleviation in managing glucose levels. They expressed discomfort and stress related to the disposal of wastes associated with fingerpicking at home that the CGM may alleviate. However, the patients also voiced concerns about the reliability, functionality, affordability, required supplies and replacements, and training and guidance. One patient had learned about CGMs from a family member with DM residing permanently outside Ethiopia who uses the device, perceiving it feasible, despite the cost.

Clinicians acknowledge the potential advantages of digital CGMs for real-time monitoring and reducing needle burden, particularly for patients prone to recurrent hypoglycemia or resistant to traditional blood sampling methods. Some clinicians possess background information about digital CGMs, although they have not yet utilized them in practice. They express a keen interest in integrating these devices into practice and they have optimism regarding their potential to improve glucose management. Nonetheless, concerns exist about training needs for both patients and clinicians, their adoption in local contexts, and affordability, particularly among economically disadvantaged patient populations. They perceive that patient acceptance may hinge on training and familiarity with the technology.

There is a positive outlook regarding the feasibility and advantages of integrating digital CGMs into patient care systems. They recognize the potential of an EHR to streamline digital CGM processes, improve communication, and enhance data management. The DM clinic utilizes EMR systems, resulting in notable efficiency, limited paperwork hurdles, and convenient access to patient histories and investigation outcomes. Nonetheless, challenges exist, such as data entry inaccuracies, prescription editing limitations, errors stemming from transferring information, difficulty in locating specific data, and lack of confidentiality. These issues are compounded by infrastructure constraints, training needs, and reliance on internet connectivity. The challenges need to be resolved to ensure successful integration of digital CGMs into existing EHR systems.

Theme 4: technology adoption

Theme four explored the perspectives of patients and clinicians concerning their adoption of technology, revealing two subthemes: exposure, and benefits and challenges. Table 5 compiles the major quotes shared by study participants in each subtheme.

Despite differences in exposure or use levels, the majority of patients have been adept at using some digital technologies like smartphones and computers. They hold a positive view of such technologies, finding them easy to use and advantageous for accessing information and services. Patients recognize the potential benefits of integrating technology into their healthcare, believing that with proper education and training, it can effectively manage health conditions. Although some patients rely on family members for digital tasks, revealing limited personal exposure to digital devices, they are open to integrating new technologies into their routines. Additionally, patients acknowledge the potential drawbacks of technology, especially when used for non-essential purposes. Clinicians generally view technology as a beneficial factor in healthcare, as it improves efficiency and enhances patient outcomes. While transitioning from paper-based to electronic systems in hospitals has posed challenges, it has ultimately proven advantageous, building greater trust and acceptance among healthcare providers and patients. Its impact is seen as positive, although it requires adaptation and staff training to fully harness its potential.

Theme 5: Financial coverage

Theme five explores patients’ and clinicians’ experiences regarding the coverage of financial expenses for their DM and HIV routine care and treatment, finding two subthemes: health insurance and out-of-pocket expenses. Table 6 summarizes the key quotes provided by study participants in each subtheme.

The majority of patients reported that their diabetes care and treatment at the hospitals were covered by health insurance, highlighting the vital role of insurance in healthcare access. This was validated by their clinicians, who noted that more than 85% of their patients with DM have insurance coverage. Additionally, patients noted that HIV-related medical expenses, including laboratory tests and medications, were covered by the hospitals, with government support facilitating this. However, patients noted that they incurred out-of-pocket expenses for private clinic laboratory tests and services not covered by their insurance, or those that are not consistently available in the hospitals. There were a few patients who had employer-sponsored health coverage, where they initially paid for medical costs and later receive reimbursement from their employer. However, they expressed frustration with the longer reimbursement process. Apart from that, the AIDS Healthcare Foundation (AHF), an international non-governmental organization, supported ART clinics by providing opportunistic infection medications and covering the expenses for diagnostic imaging like MRI and CT scans. This assistance has been part of their agreement with the private sector, specifically tailored to benefit economically disadvantaged patients. There were also a few patients who lacked these benefits and relied entirely on out-of-pocket payments.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the lived experiences of patients with HIV-DM comorbidity and their healthcare providers regarding glucose monitoring practices, as well as their receptiveness to CGM and other digital technologies, exploring the landscape for implementing digital CGM systems in a lower income country context. The findings offered formative insights for a planned implementation trial of digital CGM in Ethiopia. They describe the benefits and challenges of the current blood glucose monitoring systems, as well as the potential benefits and barriers associated with the proposed digital CGM systems, while also addressing the financial implications inherent in adopting new technologies. The thematic analysis revealed that patients with HIV-DM comorbidity were actively engaged in their DM management, and both patients and providers were open to digital CGM systems and other technological solutions while recognizing the importance of affordability and training in implementing new technologies. Previous studies conducted in African settings have underscored the significant demand for innovative strategies to manage HIV-DM comorbidity effectively39,40,41,42. To mitigate complications in patients with HIV-DM comorbidity attending care in such settings, several strategies could be deployed, with regular glucose testing being paramount. Whether it is for monitoring diabetes risk factors, promoting healthy lifestyle and behavioral changes, or monitoring treatment effectiveness, access to quality-assured, portable, and affordable glucose monitoring systems is crucial. Future practice in such settings should adopt integrated HIV-DM care in a one-stop shop model. This approach will enable comorbid patients receive timely care for both diseases at a time without the hassle of visiting multiple clinics, reduce out-of-pocket costs, and minimize redundant blood draws for laboratory tests. It allows clinicians to effectively follow-up and treat co-morbid patients, assess and manage potential drug-drug interactions and treatment side effects, and provide coordinated adherence counseling and psychosocial support.

Patients and providers in the interviews emphasize the reliance on health insurance for DM care and treatment in the clinics. The acquisition of health insurance has resolved some financial burdens, underscoring the significance of insurance coverage in healthcare access. However, patients still encounter out-of-pocket costs for tests not covered by insurance. This underscores the importance of considering cost-effectiveness when implementing digital CGM systems in such settings, especially if broader accessibility is the goal. While some studies have demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of digital CGMs compared to traditional blood glucose self-testing43,44,45, there remains limited evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Even in developed countries where CGMs are common, technical and administrative challenges, such as frequent scanning, composite metrics, data management, behavioral fitness, and equitable access, are still being addressed by developers46,47,48,49,50. Similarly, in the present study, the consistent availability of glucose testing supplies emerged as a significant challenge. This underscores the need to establish resilient systems in advance to ensure that such challenges do not persist following the introduction of digital CGMs. Some CGM systems are becoming less expensive, given their limited uptake and sustainability in underserved regions51,52, and global partnerships are exploring their potential use in these regions while seeking rebates or discounts53,54. For practical purposes, education around the benefits and use of CGMs can be offered to patients in Ethiopia to encourage its adoption and use.

In this study, both patients and clinicians expressed assurance that introducing digital CGMs would be both feasible and beneficial. They highlighted several advantages, including real-time monitoring, ease of use, elimination of the need for blood samples, reduced discomfort associated with frequent testing, integration with smartphone applications, and the potential to reduce stress associated with glucose management. In fact, all except one patient and many clinicians had not been previously informed about digital CGMs and learned about the devices during study interviewers. However, they welcomed and expressed keen interest in utilizing these devices and were open to trying them out. This finding is considered a critical milestone for any upcoming CGM RCTs in these settings, given that previous studies on CGMs in LMICs have shown several limitations and efforts remain limited to move them into LMICs24,55. Meanwhile, evidence suggests that proper familiarity and a better understanding of the systems are crucial for enhancing usability and acceptability56,57.

The findings of this study contribute to the successful implementation and evaluation of digital CGMs by offering baseline information on current glucose monitoring systems and the road ahead for digital CGMs. However, the study has some limitations. The study’s hospitals were urban and public, potentially overlooking the views of patients and providers in rural hospitals and private sectors. As well, data based on self-selected sample of patients and providers may not represent these populations in this country. However, including hospitals that serve patients from all over Ethiopia helped mitigate these limitations. Future research could explore these topics with more patients and providers and possibly investigate uptake of CGMs and their facilitators. Conducting interviews in healthcare facilities where the patients receive care may have introduced agreement bias, with participants adjusting their answers to align with what they believed the researchers wanted. This bias was minimized by using open-ended questions that promoted deeper reflection and elaboration instead of just agreement or disagreement.

Conclusion

This qualitative phenomenological study explored the lived experiences of patients with HIV-DM comorbidity and their healthcare providers, providing formative insights for a planned implementation trial of digital CGM in Ethiopia. The thematic analysis identified five main themes: “Diabetes routine clinical care and follow-up”, “Blood glucose monitoring practices”, “Perceptions about digital CGMs”, “Technology adoption”, and “Financial coverage”. In this study, the lived experience of the participants demonstrate that many of them had not been previously informed about digital CGMs, but they welcomed and expressed keen interest in trying them out and utilizing, a development seen as a critical milestone for any upcoming CGM clinical trials in these settings. Participants were open to digital CGM systems and other technological solutions while recognizing the importance of affordability and training in implementing new technologies. They emphasize the reliance on health insurance for DM care and treatment in the clinics but encounter out-of-pocket costs for tests not covered by insurance, underscoring the importance of considering cost-effectiveness when implementing digital CGM systems in such settings. The findings can serve as a foundation for future implementation research aimed at investigating the effectiveness of CGM systems in the context of developing countries, as well as exploring the associated implementation barriers and opportunities.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Teufel, F., Bulstra, C. A., Davies, J. I. & Ali, M. K. Enhancing global access to diabetes medicines: policy lessons from the HIV response. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 12, 88–90 (2024).

Daultrey, H., Levett, T., Oliver, N. & Vera, J. Chakera, A. HIV and type 2 diabetes: an evolving story. HIV Med. 25, 409–423 (2024).

Tysoe, O. A novel system for non-invasive measurement of blood levels of glucose. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 20, 320 (2024).

Moses, J. C. et al. Non-invasive blood glucose monitoring technology in diabetes management: review. Mhealth. 10, 9 (2023).

Laha, S., Rajput, A., S Laha, S. & Jadhav, R. A concise and systematic review on non-invasive glucose monitoring for potential diabetes management. Biosens. (Basel). 12, 965 (2022).

Tang, L., Chang, S. J., Chen, C. J. & Liu, J. T. Non-invasive blood glucose monitoring technology: a review. Sens. (Basel). 20, 6925 (2020).

Abbott Laboratories Ltd. FreeStile Libre. Alpharetta, Georgia, US. https://www.freestyle.abbott/us-en/home.html

Dexcom Inc. Dxcom G6. San Diego, CA, US. https://www.dexcom.com/en-us

Mita, T. Do digital health technologies hold promise for preventing progression to type 2 diabetes? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 109, e1667–e1668 (2024).

Fleming, G. A. Diabetes Digital App Technology: benefits, challenges, and recommendations. A Consensus Report by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) Diabetes Technology Working Group. Diabetes Care. 43, 250–260 (2020).

Manyazewal, T. et al. Mapping digital health ecosystems in Africa in the context of endemic infectious and non-communicable diseases. NPJ Digit. Med. 6, 97 (2023).

International Diabetes Federation (IDF). IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th Edn (Brussels, 2021). https://diabetesatlas.org/data/en/country/67/et.htmlBelgium; IDF 2021.

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Global HIV & AIDS statistics, 2022. Geneva, Switzerland; UNAIDS 2022. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet

Getahun, Z., Azage, M., Abuhay, T. & Abebe, F. Comorbidity of HIV, hypertension, and diabetes and associated factors among people receiving antiretroviral therapy in Bahir Dar City, Ethiopia. J. Comorb. 10, 2235042X19899319 (2020).

Faurholt-Jepsen, D. et al. Hyperglycemia and insulin function in antiretroviral treatment-naive HIV patients in Ethiopia: a potential new entity of diabetes in HIV? AIDS 33, 1595–1602 (2019).

Ataro, Z., Ashenafi, W., Fayera, J. & Abdosh, T. Magnitude and associated factors of diabetes mellitus and hypertension among adult HIV-positive individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy at Jugal Hospital, Harar, Ethiopia. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 10, 181–192 (2018).

Abebe, S. M. et al. Diabetes mellitus among HIV-infected individuals in follow-up care at University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMJ Open. 6, e011175 (2016).

Manyazewal, T., Woldeamanuel, Y., Blumberg, H. M., Fekadu, A. & Marconi, V. C. The potential use of digital health technologies in the African context: a systematic review of evidence from Ethiopia. NPJ Digit. Med. 4, 125 (2021).

Manyazewal, T., Woldeamanuel, Y., Fekadu, A., Holland, D. P. & Marconi, V. C. Effect of Digital Medication event reminder and monitor-observed therapy vs Standard Directly Observed Therapy on Health-Related Quality of Life and Catastrophic costs in patients with tuberculosis: a secondary analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 5, e2230509 (2022).

Manyazewal, T., Woldeamanuel, Y., Holland, D. P., Fekadu, A. & Marconi, V. C. Effectiveness of a digital medication event reminder and monitor device for patients with tuberculosis (SELFTB): a multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 20, 310 (2022).

Manyazewal, T. et al. Patient-reported usability and satisfaction with electronic medication event reminder and monitor device for tuberculosis: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. EClinicalMedicine 56, 101820 (2023).

Ethiopian Ministry of Health (MoH). Standards for electronic health record (HER) system in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; MoH (2021). https://e-library.moh.gov.et/library/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Standard-for-Electronic-Health-Record-System-EHR-in-Ethiopia.pdf

Ethiopian Ministry of Health (MoH). Digital Health Blueprint. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; MoH 2021. https://e-library.moh.gov.et/library/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Ethiopian-Digital-Health-Blueprint.pdf

Thapa, A. et al. Appropriateness and acceptability of continuous glucose monitoring in people with type 1 diabetes at rural first-level hospitals in Malawi: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 14, e075559 (2024).

Kang, H. S., Park, H. R., Kim, C. J. & Singh-Carlson, S. Experiences of using Wearable continuous glucose monitors in adults with diabetes: a qualitative descriptive study. Sci. Diabetes Self Manag Care. 48, 362–371 (2022).

Sergel-Stringer, O. T. et al. Acceptability and experiences of real-time continuous glucose monitoring in adults with type 2 diabetes using insulin: a qualitative study. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 23, 1163–1171 (2024).

Sehgal, S. et al. Do-it-yourself continuous glucose monitoring in people aged 16 to 69 years with type 1 diabetes: a qualitative study. Diabet. Med. 41, e15168 (2024).

Karakuş, K. E. et al. Benefits and drawbacks of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) use in Young Children with type 1 diabetes: a qualitative study from a Country where the CGM is not reimbursed. J. Patient Exp. 8, 23743735211056523 (2021).

Badacho, A. S. & Mahomed, O. H. Lived experiences of people living with HIV and hypertension or diabetes access to care in Ethiopia: a phenomenological study. BMJ Open. 14, e078036 (2024).

Muhammed, O. S. et al. Treatment burden and regimen fatigue among patients with HIV and Diabetes attending clinics of Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital. Sci. Rep. 14, 5221 (2024).

Oluma, A., Abadiga, M., Mosisa, G. & Etafa, W. Magnitude and predictors of poor glycemic control among patients with diabetes attending public hospitals of Western Ethiopia. PLoS One. 16, e0247634 (2021).

Gobena, M. G. & Kassie, M. Z. Determinants of blood sugar level among type I diabetic patients in Debre Tabor General Hospital, Ethiopia: a longitudinal study. Sci. Rep. 12, 9035 (2022).

Oluma, A. et al. Predictors of adherence to Self-Care Behavior among patients with diabetes at Public Hospitals in West Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 13, 3277–3288 (2020).

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Guideline Recommendations on Digital Interventions for Health System Strengthening (WHO, 2019). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550505

Ali, H. A., Abebe, B., Moges, A. & Deyessa, N. Behavioural abnormalities among school-age children living with HIV at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 20, 307–313 (2021).

Yazie, T. S. Dyslipidemia and Associated Factors in Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate-based Regimen among Human Immunodeficiency Virus-infected Ethiopian patients: a hospital-based observational prospective cohort study. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 12, 245–255 (2020).

St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College (SPHMMC). SPHMMC at a GlanceSPHMMC (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2022). https://sphmmc.edu.et/about/

Andarge, D. E., Hailu, H. E. & Menna, T. Incidence, survival time and associated factors of virological failure among adult HIV/AIDS patients on first line antiretroviral therapy in St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College-A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 17, e0275204 (2022).

Bam, N. E. et al. Lifestyle determinants of diabetes mellitus amongst people living with HIV in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam Med. 14, e1–e7 (2022).

Birungi, J. et al. Integrating health services for HIV infection, diabetes and hypertension in sub-saharan Africa: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 11, e053412 (2021).

Tamuhla, T., Dave, J. A., Raubenheimer, P. & Tiffin, N. Diabetes in a TB and HIV-endemic South African population: analysis of a virtual cohort using routine health data. PLoS One. 16, e0251303 (2021).

Bosire, E. N. Patients’ experiences of Comorbid HIV/AIDS and Diabetes Care and Management in Soweto, South Africa. Qual. Health Res. 31, 373–384 (2021).

Isitt, J. J. et al. Cost-effectiveness of a real-time continuous glucose monitoring system Versus Self-Monitoring of blood glucose in people with type 2 diabetes on insulin therapy in the UK. Diabetes Ther. 13, 1875–1890 (2022).

Roze, S., Isitt, J., Smith-Palmer, J., Javanbakht, M. & Lynch, P. Long-term cost-effectiveness of Dexcom G6 Real-time continuous glucose monitoring Versus Self-Monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 1 diabetes in the U.K. Diabetes Care. 43, 2411–2417 (2020).

Jendle, J. et al. Cost-effectiveness of the FreeStyle Libre® System Versus blood glucose self-monitoring in individuals with type 2 diabetes on insulin treatment in Sweden. Diabetes Ther.12, 3137–3152 (2021).

ISCHIA Study Group. Predictors of the effectiveness of isCGM usage in adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus: post-hoc analysis of the ISCHIA study. Diabetol. Int. 15, 400–405 (2024).

Gómez-Peralta, F. et al. Impact of continuous glucose monitoring and its glucometrics in clinical practice in Spain and Future perspectives: a narrative review. Adv. Ther. 41, 3471–3488 (2024).

den Braber, N. et al. Consequences of data loss on clinical decision-making in continuous glucose monitoring: Retrospective Cohort Study. Interact. J. Med. Res. 13, e50849 (2024).

Ni, K., Tampe, C. A., Sol, K., Cervantes, L. & Pereira, R. I. Continuous glucose monitor: reclaiming type 2 diabetes self-efficacy and mitigating disparities. J. Endocr. Soc. 8, bvae125 (2024).

Lin, Y. K. et al. You have to use everything and come to some equilibrium’: a qualitative study on hypoglycemia self-management in users of continuous glucose monitor with diverse hypoglycemia experiences. BMJ Open. Diabetes Res. Care. 11, e003415 (2023).

Ballard, L., York, A. L., Skelley, J. W. & Sims, M. Clinical and financial outcomes of a pilot pharmacist-led continuous glucose monitoring clinic. Innov. Pharm. 15 https://doi.org/10.24926/iip.v15i1.6081 (2024).

Natale, P. et al. Patient experiences of continuous glucose monitoring and sensor-augmented insulin pump therapy for diabetes: a systematic review of qualitative studies. J. Diabetes. 15, 1048–1069 (2023).

McClure Yauch, L. et al. Continuous glucose monitoring assessment of metabolic control in east African children and young adults with type 1 diabetes: a pilot and feasibility study. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 3, e00135 (2020).

Karachaliou, F., Simatos, G. & Simatou, A. The challenges in the Development of Diabetes Prevention and Care models in low-income settings. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 11, 518 (2020).

Bernabe-Ortiz, A., Carrillo-Larco, R. M., Safary, E., Vetter, B. & Lazo-Porras, M. Use of continuous glucose monitors in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Diabet. Med. 40, e15089 (2023).

Hirsch, I. B. & Miller, E. Integrating continuous glucose monitoring into clinical practices and patients’ lives. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 23, S72–S80 (2021).

Søholm, U. et al. Assessing the content validity, acceptability, and feasibility of the Hypo-METRICS app: survey and interview study. JMIR Diabetes. 8, e42100 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the US National Institutes of Health (D43TW011404) and the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30AI050409). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US National Institutes of Health or the Emory Center for AIDS Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: T.M., M.K.A., V.C.M, T.K; Methodology: T.M., M.K.A., V.C.M, T.K. S.A.P., C.E., Data curation: T.M., S.S., T.G., M.J., T.K.; Analysis and validation: T.M., V.C.M., M.K.A., T.K., S.S., D.H., S.A.P., C.E., Y.W., F.M., M.J., T.G., W.A., A.F. Funding acquisition: T.M., M.K.A., A.F., V.C.M., D.H. Draft the manuscript: T.M.; Reviewed and revised the manuscript: T.M., V.C.M., M.K.A., T.K., S.S., D.H., S.A.P., C.E., Y.W., F.M., M.J., T.G., W.A., A.F. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

V.C.M. has received investigator-initiated research grants (to the institution) and consultation fees (both unrelated to the current work) from Eli Lilly, Bayer, Gilead Sciences, Merck, and ViiV. M.K.A. has received investigator-initiated research grants to the institution from Merck and consultation fees (both unrelated to the current work) from Eli Lilly and Bayer. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Manyazewal, T., Ali, M.K., Kebede, T. et al. Digital continuous glucose monitoring systems for patients with HIV-diabetes comorbidity in Ethiopia: a situational analysis. Sci Rep 14, 28862 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79967-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79967-y