Abstract

Quantum computing is on the cusp of transforming the way we tackle complex problems, and the Grover search algorithm exemplifying its potential to revolutionize the search for unstructured large datasets, offering remarkable speedups over classical methods. Here, we report results for the implementation and characterization of a three-qubit Grover search algorithm using the state-of-the-art scalable quantum computing technology of superconducting quantum architectures. To delve into the algorithm’s scalability and performance metrics, our investigation spans the execution of the algorithm across all eight conceivable single-result oracles, alongside nine two-result oracles, employing IBM Quantum’s 127-qubit quantum computers. Moreover, we conduct five quantum state tomography experiments to precisely gauge the behavior and efficiency of our implemented algorithm under diverse conditions – ranging from noisy, noise-free environments to the complexities of real-world quantum hardware. By connecting theoretical concepts with real-world experiments, this study not only shed light on the potential of Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum Computers in facilitating large-scale database searches but also offer valuable insights into the practical application of the Grover search algorithm in real-world quantum computing applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum computing has emerged as a transformative field with the potential to revolutionize various domains, including quantum machine learning (QML)1, cryptography2, combinatorial optimization3, quantum chemistry4, drug discovery5, and long distance quantum communications6,7. At the heart of quantum computing lies the promise of harnessing quantum phenomena to perform computations at unprecedented speeds, surpassing the capabilities of classical computers8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16.

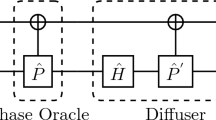

A schematic circuit representation illustrating the key stages of GSA. The process includes initialization, where the qubits are prepared in a superposition state; marking, where the target item (items) in the database are identified and marked by the oracle; amplification, where the amplitude(s) of the marked item(s) are increased; and measurement, where the final result is obtained. Here, \(\left| 0\right\rangle\), H, and X represent the initialization of the qubit to the \(\left| 0\right\rangle\) state, the Hadamard gate, and Pauli’s X gate, respectively.

Searching through extensive databases is a crucial challenge with far-reaching applications. Among the plethora of quantum algorithms developed thus far, Grover’s search algorithm (GSA) stands out as a powerful technique for searching unsorted databases17,18. Proposed by Lov Grover in 1996, this algorithm offers a quadratic speedup over classical algorithms, making it particularly attractive for a wide range of applications17.

Grover’s algorithm occupies a central position within the realm of quantum computing, heralded for its versatility and utility across numerous disciplines. It stands as the optimal search algorithm for quantum architectures19, finding utility as a foundational component for quantum algorithms20,21. Its applicability extends to facilitating string matching tasks22, addressing minimum search challenges23, tackling computational geometry problems24. and enabling quantum dynamic programming25. Successful demonstrations of searches employing two qubits have been achieved across different quantum platforms26,27,28,29,30,31,32. However, efforts to expand these capabilities to larger search spaces have primarily been demonstrated on non-scalable NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) systems33. Additionally, a three-qubit GSA using programmable trapped atomic ion systems was implemented in34.

Recent advancements in implementing GSA on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices and superconducting quantum platforms have significantly progressed. Notably, prior implementations have demonstrated varying levels of success probabilities, with some achieving better-than-classical performance across various quantum computing platforms34,35,36,37,38,39. However, these implementations have generally been limited to relatively small values of S. For instance, better-than-classical success rates were achieved for \(n = 3\)34,36 and \(n = 4\) qubits38. The most extensive implementation to date involves \(n = 8\) qubits, but this has not yet surpassed classical success probabilities35. The study in39 demonstrated improved success probabilities for \(n = 5\) with a single marked state (\(\left| 01011\right\rangle\)); however, averaging over multiple marked states (\(2^5\)) may decrease these probabilities. More recent advancements, such as those reported in40, utilized IBM Quantum’s two 7-qubit systems to achieve superior average success probabilities for \(n \le 5\) through error suppression techniques. Additional progress in Grover’s algorithm on NISQ devices can be found in38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45, reflecting ongoing improvements and innovative approaches. Recently, significant progress towards practical quantum computing using a 127-qubit superconducting quantum processor is demonstrated in46, achieving meaningful computational results despite the challenges of noise and lack of fault tolerance. Encouraged by these advancements, our research leverage similar cutting-edge technology, exploring the potential for scalable and efficient GSA implementations in such quantum hardware.

The motivation behind our research lies in the growing interest in practical quantum computing and the necessity to comprehend the experimental feasibility and performance of implementing quantum algorithms on real quantum hardware, especially within the NISQ era. This paper presents a comprehensive study focusing on the experimental implementation and characterization of the GSA on large-scale superconducting quantum computers. Leveraging state-of-the-art quantum hardware, we aim to explore the scalability, performance, and practical challenges associated with deploying Grover’s algorithm in real-world settings.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 begins with an overview of the experimental setup and implementation details, detailing the procedures and methodologies employed to realize the GSA on the real quantum hardware. In Section 2, we delve into the intricacies of quantum circuit design, oracle construction, and quantum state preparation, laying the groundwork for our experimental investigations. Subsequently, in Section 3, we conduct a thorough characterization of the implemented algorithm, employing \({\mathcal {QST}}\) (quantum state tomography). We design and perform \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments, allowing us to assess the algorithm’s performance across different configurations and environmental conditions, including noise-free, noisy, and real quantum hardware. To our knowledge, similar QST experiments have not been conducted on comparable architectures. We analyze key metrics such as algorithm success probability (\({\mathcal {ASP}}\)), squared statistical overlap (\({\mathcal {SSO}}\)), and state fidelity (\(\mathcal {F}_S\)), providing insights into the algorithm’s behavior and its suitability for practical applications. Furthermore, Section 4 includes a detailed analysis and discussions, where we interpret our experimental findings, compare them with theoretical expectations, and explore implications for future research and development in quantum computing. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper with a summary of our findings and suggestions for future research directions.

Experimental setup and implementations

Problem statement

Grover’s algorithm addresses the problem of unstructured search. In this context, an unstructured search problem entails having a set of S elements forming a set \(\Upsilon = \{\gamma _1, \gamma _2, \dots , \gamma _S\}\), along with a boolean function \(f :\Upsilon \rightarrow \{0, 1\}\). The objective is to identify an element \(\gamma ^*\) in \(\Upsilon\) for which \(f(\gamma ^*) = 1\).

For instance, consider a scenario where we are searching for a specific phone number in a directory. The function \(f(\gamma )\) evaluates whether a given phone number matches the desired one. The essence of the problem lies in its abstraction, such that any search task can be distilled into an evaluation of a function \(f(\gamma )\), where \(\gamma\) represents potential search items. Should a particular item \(\gamma\) hold the solution, the function returns 1; otherwise, it returns 0. Thus, the fundamental challenge (search problem) is to uncover any such \(\gamma ^*\) that yields a result of 1.

Grover’s algorithm embarks on this quest by tackling a classical function (\(f(\gamma ): \{0,1\}^n \rightarrow \{0,1\}\)), where n denotes the bit-size of the search space. In the classical realm, the algorithm’s complexity hinges on the sheer number of times the function \(f(\gamma )\) must be interrogated. In the most unfavorable scenario, this involves an exhaustive search through \(S-1\) iterations, where \(S=2^n\), exhaustively exploring every conceivable option. However, GSA offers a profound departure from this laborious approach, promising a remarkable quadratic acceleration. Specifically, this signifies that the algorithm can ascertain the sought-after solution with a mere \(\mathcal {O}(\sqrt{S})\) evaluations, a stark contrast to the linear S evaluations demanded by classical methods17.

Methodology

Grover’s algorithm not only revolutionizes the speed at which search tasks are accomplished but also epitomizes the transformative potential of quantum computing in navigating complex computational landscapes with unprecedented efficiency. Its methodology comprises several pivotal stages: initialization, marking, amplification, and measurement, as depicted in Figure 1. The algorithm initiates with an input state \(\left| \zeta _0\right\rangle = \sum _{\chi =0}^{S-1} \left| \chi \right\rangle \rightarrow \left| 0\right\rangle ^{\otimes n}\), where it establishes a superposition of all potential search states, \(H^{\otimes n} \left| \zeta _0\right\rangle \rightarrow \left| \zeta _1\right\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{S}}\sum _{\chi =0}^{S-1} \left| \chi \right\rangle\), laying the groundwork for quantum parallelism. Subsequently, during the marking phase, an oracle function (\(\mho _f:\left| \chi \right\rangle \rightarrow (-1)^{f(\chi )} \left| \chi \right\rangle\)) is employed to identify and mark the target state \(\left| \chi ^*\right\rangle\) or states within the superposition. These oracle functions alter the sign of the amplitude of the marked state(s). Mathematically, for a single-search result scenario, it can be represented as \(\left| \zeta _2\right\rangle = -\frac{1}{\sqrt{S}} \left| \chi ^*\right\rangle + \frac{1}{\sqrt{S}} \sum _{\chi =0,\chi \ne \chi ^*}^{S-1} \left| \chi \right\rangle\). This marking process is crucial as it enables the algorithm to concentrate computational resources on the desired outcome.

The heart of Grover’s algorithm lies in the amplification phase (see Figure 1), where a Grover operator (\(\mathcal{G}\mathcal{O}\)) is iteratively applied to boost the probability amplitude of the marked state(s) while simultaneously diminishing the amplitudes of non-marked states. The \(\mathcal{G}\mathcal{O}\) involves reflections about the mean (\(\mu _G = \frac{1}{S} \sum _{\chi =0}^{S-1} \varpi _{\chi }\)) so that \(\left| \zeta _3\right\rangle = -\varpi _{\chi ^*} \left| \chi ^*\right\rangle + \varpi _{\chi } \sum _{\chi =0,\chi \ne \chi ^*}^{S-1} \left| \chi \right\rangle\), and inversions about the marked state, \(\left| \zeta _4\right\rangle = (2 \mu _G + \varpi _{\chi ^*}) \left| \chi ^*\right\rangle + (2 \mu _G - \varpi _{\chi }) \sum _{\chi =0,\chi \ne {\chi ^*} }^{S-1} \left| \chi \right\rangle\), where \(\varpi _{\chi }\) denotes the amplitude for the basis state \(\left| \chi \right\rangle\). This iterative process is pivotal in achieving the algorithm’s remarkable time complexity of \(\mathcal {O}(\sqrt{S})\), representing a quadratic speedup over classical search algorithms. Finally, the algorithm concludes with a measurement stage, wherein the quantum state is measured, yielding the marked item(s) with high probability. The correctness of the algorithm is validated by assessing the probability of measuring the marked state.

Design and execution of quantum oracles

Here, we implement the GSA using state-of-the-art scalable superconducting quantum computers, utilizing \(n = 3\) qubits, which corresponds to a search database of size \(S = 2^n = 8\). Table 1 illustrates the phase oracles alongside their corresponding boolean oracles for all eight single-marked states employed in the 3-qubit GSA. These marked states are: \(\left| 000\right\rangle , \, \left| 001\right\rangle\), \(\left| 010\right\rangle , \, \left| 011\right\rangle\), \(\left| 100\right\rangle , \, \left| 101\right\rangle\), \(\left| 110\right\rangle , \, \text {and} \left| 111\right\rangle\). Additionally, we scrutinize the performance of the GSA with nine distinct two-search phase oracles (as depicted in Table 2), each uniquely designed to mark two states within the search space. The marked states include: \(\left| 000\right\rangle -\, \left| 111\right\rangle\), \(\left| 001\right\rangle -\, \left| 100\right\rangle\), \(\left| 011\right\rangle -\, \left| 100\right\rangle\), \(\left| 010\right\rangle -\, \left| 111\right\rangle\), \(\left| 000\right\rangle -\, \left| 110\right\rangle\), \(\left| 010\right\rangle -\, \left| 101\right\rangle\), \(\left| 101\right\rangle -\, \left| 110\right\rangle\), \(\left| 101\right\rangle -\, \left| 111\right\rangle\), and \(\left| 100\right\rangle -\, \left| 111\right\rangle\). In our experimental setups, we employ the GSA with phase oracles, a technique previously verified in other experimental configurations. It is noteworthy that both phase and boolean oracles exhibit mathematical equivalence47.

The likelihood of detecting the designated state following k iterations of the \(\mathcal{G}\mathcal{O}\) is a crucial metric for evaluating the algorithm’s efficiency. This likelihood is articulated by the expression:

This formulation arises from the amplitude amplification process18, delineating the probability amplitude alterations occurring at each iteration.

In the case of a single-solution algorithm with \(k = 1\) iteration in GSA, the algorithmic probability of measuring the correct state after one iteration results in approximately \(78.125\%\). This probability is significantly higher than the probability achieved by the optimal classical search strategy, which consists of a single query followed by a random guess in case of failure. In the classical strategy, the probability is calculated as:

For this case, it equals \(25\%\), where k represents the number of correct answers (1 in this case) and \(\pounds\) represents the total number of possible answers34. This comparison highlights the quantum advantage of GSA over classical search strategies, demonstrating its superior efficiency in finding solutions with fewer queries, especially in scenarios with a single correct answer.

Quantum circuits construction

The complexity of circuit transpilation increases with problem size, particularly due to the need for decomposing multi-qubit gates. Implementing the n-qubit GSA necessitates the use of the n-qubit controlled-phase gate, denoted \(\Gamma _{n-1}(Z)\). This multi-qubit gate is critical for both the oracle and the amplitude amplification steps of the algorithm40. The \(\Gamma _{n-1}(Z)\) gate can be realized through the decomposition of the n-qubit Toffoli gate, denoted \(\Gamma _{n-1}(X)\). This decomposition is resource-intensive. Consequently, circuits with multiple Toffoli gates tend to have significant depth, which can increase their susceptibility to noise and gate errors.

In practical quantum devices, such as NISQ superconducting devices, the challenge of implementing multi-controlled NOT gates is compounded by limited qubit connectivity, making such decomposition’s into two-qubit gates more complex. For instance, each three-qubit Toffoli gate (\(\Gamma _{2}(X)\) or CCX) in a quantum circuit can require up to six CNOT gates in addition to several single-qubit gates47. However, this decomposition assumes a fully connected quantum architecture, which is not always available in practical quantum devices. Alternative circuit decomposition, for linear connected three qubits, such as the decomposition of the three-qubit \(\Gamma _{2}(Z)\) gate into eight CNOT gates have been explored in38,39,40. This scheme, utilizing specific relative phase Toffoli gates48 can be generalized to implement the n-qubit GSA40.

In our experiments, the quantum hardware leveraged a two-qubit gate, known as the ECR (Echoed Cross-Resonance) gate, rather than using the conventional CNOT gate. In our implementations, the CCX gate is decomposed into nine ECR gates49, see Eq. (3). Leveraging the ECR gate’s advanced capabilities, including enhanced entanglement and error mitigation, which are particularly well-suited for the specific needs of our experiments.

The ECR gate is a maximally entangling gate, functions similarly to the CNOT gate through a distinct mechanism that is optimized for the specific architecture of the hardware50. In particular, the \(ECR^{q_0}_{q_1}\) gate implements the operation \((IX-XY)/\sqrt{2}\), where I is the identity matrix, X and Y are Pauli matrices, with \(R_z\) are single-qubit rotations about the z axis. This echoing process improves the gate’s performance in practical experiments by mitigating errors and preserving the fidelity of the quantum state. See Eq. (4) for ECR’s matrix representations.

Results overview

The \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) encapsulates the probability of successfully identifying the marked state as the conclusive result of an experiment. In the case of a two-solution algorithm, \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) is determined by aggregating the probabilities associated with observing each of the two marked states. Meanwhile, the \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) offers a quantitative measure of the extent to which observed and expected populations overlap across all states. The \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) is calculated as follows:

Here, \(\xi _m\) represents the expected population for each state m, while \(\mathcal {M}_m\) signifies the measured population for each state m, and M denotes the total number of states. This formulation of \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) is often used in various fields, including population studies, where it quantifies the similarity or overlap between observed and expected population distributions across different categories or states51.

In our investigation, we delved into executions of the GSA for both single-solution and two-solution scenarios on a 3-qubit database, exploring diverse environmental conditions such as noisy environments and leveraging real quantum computers provided by IBM Quantum52. Specifically, we employed three of IBM’s 127-qubit superconducting quantum computers: ibm_sherbrook. ibm_osaka, and ibm_kyoto. These quantum machines are equipped with Eagle r3 quantum processors, boasting capabilities of executing a maximum of 300 circuits and 100,000 shots. For further insights, the key specifications and qubit characteristics of these 127-qubit quantum computers, including error rates for individual gates and readout, as well as their basis gates, are meticulously outlined in Section 5.

While acknowledging the theoretical optimality of GSA, which suggests a runtime of \(\mathcal {O}(\sqrt{S})\) iterations to locate the marked state within a search space of size S, our experimental implementations were tailored to address the practical realities of quantum hardware, while still showcasing the algorithm’s effectiveness. Thus, we iterate the \(\mathcal{G}\mathcal{O}\) ten times for each oracle, guided by the prevalent challenges posed by errors and noise in real-world quantum hardware, particularly in the NISQ era.

For the single-solution scenarios, we observed intriguing outcomes (see Figure 2). In the presence of noise, our analysis revealed an average \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) of \(78.39\%\), indicating the algorithm’s capability to consistently identify the correct solution amidst environmental disturbances. However, when executed on IBM Quantum’s real quantum computers, the \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) decreased to \(51.19\%\), underscoring the challenges encountered in practical quantum computing environments. Furthermore, our investigation into the \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) metrics provided deeper insights. In noisy environments, we recorded an average \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) of \(82.358\%\), reflecting the algorithm’s ability to closely approximate the target state despite environmental noise. Conversely, on real IBM quantum computers, the average \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) decreased to \(73.12\%\), indicating the degree of deviation from the expected state.

Transitioning to the two-solution scenarios, our findings revealed notable trends (see Figure 3). In noisy executions, the algorithm displayed a robust performance, achieving an average \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) of \(84.44\%\). However, on IBM Quantum’s real quantum computers, the \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) reduced to \(64.44\%\), suggesting the impact of practical constraints on algorithmic efficacy. Examining the \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) values in these scenarios provided additional insights. In noisy environments, the average \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) was \(84.03\%\), indicating a satisfactory overlap with the expected state despite noise. Conversely, on real IBM quantum computers, the average \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) decreased to \(63.10\%\), highlighting the challenges encountered in achieving precise outcomes in practical quantum computing in the NISQ era.

Results obtained from executing the GSA for single-solution scenarios on a 3-qubit database (000, 001, 010, 011, 100, 101, 110, 111) in various environments. The left side presents data from algorithm execution in a noisy environment, while the right side displays data from execution on IBM Quantum’s real quantum computers. The graphs illustrate the probability distribution for each output state. We observed a median \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) of 76.79% in the noisy execution and 44.80% on the IBM quantum computers. Additionally, we obtained a median \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) of 82.49% in the noisy environment and 72.63% on real IBM quantum computers. All percentages are calculated relative to the expected state \(\left| \psi _E\right\rangle _\text {Single}\), defined as \(\left| \psi _E\right\rangle _\text {Single} = \frac{5}{4\sqrt{2}} \left| \chi ^*\right\rangle +\frac{1}{4\sqrt{2}} \sum _{\chi \ne \chi ^*} \left| \chi \right\rangle\), where \(\left| \chi ^*\right\rangle\) represents the single marked state. The \(\left| \,\right\rangle\) notation was omitted from the figures for simplicity.

Results derived from executing the GSA for nine two-solution scenarios in various environments on a 3-qubit database. The data from algorithm execution in a noisy environment is presented on the left, while data from execution on IBM Quantum’s real quantum computers is displayed on the right. The graphs depict the probability distribution for each output state. We observed an average \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) of 84.44% in the noisy execution and 64.44% on the IBM quantum computers. Additionally, we obtained an average \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) of 84.03% in the noisy environment and 63.10%, on real IBM quantum computers. All percentages are calculated relative to the expected state \(\left| \psi _E\right\rangle _\text {Multi}\), defined as \(\left| \psi _E\right\rangle _\text {Multi} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left| \chi ^*_1\right\rangle +\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left| \chi ^*_2\right\rangle\), where \(\left| \chi ^*_1\right\rangle\) and \(\left| \chi ^*_2\right\rangle\) represents the two marked states.

Experimental characterization of the Grover search algorithm

\({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments

\({\mathcal {QST}}\) plays a pivotal role in the development and validation of quantum technologies by providing a comprehensive characterization of quantum states53,54,55. It allows extracting essential information about the state of a quantum system, enabling precise assessment of quantum operations’ fidelity and performance53,54,56,57,58,59,60. By reconstructing quantum states experimentally, \({\mathcal {QST}}\) helps identify and quantify sources of errors, assess the effectiveness of error mitigation techniques, and verify the fidelity of quantum gates and algorithms61,62,63,64. Moreover, it serves as a crucial tool for benchmarking and calibrating quantum devices, facilitating progress towards achieving reliable and scalable quantum computation and communication protocols65,66.

Here, we undertake a comprehensive exploration through five \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments to meticulously evaluate the behavior and efficiency of our implemented algorithm under varied conditions. Specifically, we conduct two \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments for the GSA employing single search oracles-\(\left| 010\right\rangle\) and \(\left| 101\right\rangle\). Moreover, three additional \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments are meticulously performed for the GSA utilizing two search oracles–\(\left| 000\right\rangle -\left| 111\right\rangle\), \(\left| 101\right\rangle -\left| 110\right\rangle\), and \(\left| 101\right\rangle -\left| 111\right\rangle\). These experiments are meticulously executed across three distinct environments: a pristine noise-free setting, a simulated noisy environment, and on IBM Quantum’s tangible quantum computers. For each setting, we measured the state fidelity of the output states produced by the algorithm. The state fidelity represents the similarity between the output states and the desired target states, \(0 \le {\mathcal {F}}_{\mathcal {S}} \le 1\), with higher fidelity values indicating better performance47,67.

In the pursuit of authenticity, when executing our experiments on genuine quantum computers, we meticulously perform \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments for the GSA with single-marked states \(\left| 010\right\rangle\) and \(\left| 101\right\rangle\), employing 1024 and 7779 shots, respectively. The resultant state fidelities \({\mathcal {F}}_{\mathcal {S}}\) are found to be 49.23291% and 53.88754%, respectively. Additionally, for \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments involving two-marked states (two search oracles)–\(\left| 000\right\rangle -\left| 111\right\rangle\), \(\left| 101\right\rangle -\left| 110\right\rangle\), and \(\left| 101\right\rangle -\left| 111\right\rangle\)–we replicate the experiments using 7779, 1024, and 1024 shots, respectively. The corresponding state fidelities are observed to be 57.21854%, 49.23291%, and 68.94187%, respectively. The choice of varying numbers of shots for the \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments was employed to ensure sufficient statistical sampling and improve the reliability of the results. The outcomes gleaned from \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments of the GSA on real quantum computers, utilizing both single-search oracles and two-search oracles, are meticulously presented in Figures 4 and 5, respectively.

Upon examining the results across the three distinct environments, a notable degradation in performance is observed as we transition from the noise-free setting (mean \({\mathcal {F}}_{\mathcal {S}} = 99.38 \%\)) to the noisy setting (mean \({\mathcal {F}}_{\mathcal {S}} = 78.13 \%\)), and further to the real quantum computer setting (mean \({\mathcal {F}}_{\mathcal {S}} = 54.32 \%\)). In our \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments conducted on a real superconducting quantum computer for the GSA with different oracles, with a mean \({\mathcal {F}}_{\mathcal {S}}\) of \(54.32 \%\) and a standard deviation of 0.099, the algorithm demonstrates a moderate level of consistency in generating quantum states resembling the target state. These findings suggest that while the GSA shows promise in surpassing classical random search strategies, there remains room for improvement to achieve higher and more consistent fidelity. Further experimental investigation could elucidate potential avenues for refinement, ultimately advancing the algorithm’s efficacy in quantum search applications.

Results from \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments on the GSA with single-search oracles in different environments. (a) Real (Re.\((\rho )\)) and imaginary (Im.\((\rho )\)) parts of the density matrix obtained from \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments for the single-search marked state \(\left| 010\right\rangle\), executed with 7797 repeated shots in a noisy environment, (b) and 1024 repeated shots on IBM Quantum’s 127-qubit superconducting quantum computer ibm_osaka, yielding state fidelities (\(\mathcal {F}_S\)) of 73.9426% and 49.2329%, respectively. (c) Re.\((\rho )\) and Im.\((\rho )\) parts of the density matrix obtained from \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments for the single-search marked state \(\left| 101\right\rangle\), executed with 7797 repeated shots in a noisy environment, (d) and 7797 repeated shots on ibm_osaka, yielding \(\mathcal {F}_S\) of 73.8057% and 53.8875%, respectively.

Results from \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments of the GSA employing two-search oracles in different environments. (a) Real (Re.\((\rho )\)) and imaginary (Im.\((\rho )\)) parts of the density matrix obtained from \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments for the two-search marked states \(\left| 000\right\rangle\) and \(\left| 111\right\rangle\), executed with 7797 repeated shots in a noisy environment, (b) and 7797 repeated shots on IBM Quantum’s 127-qubit superconducting quantum computer ibm_osaka, yielding state fidelities (\(\mathcal {F}_S\)) of 78.2769% and 57.2185%, respectively. (c) Re.\((\rho )\) and Im.\((\rho )\) parts of the density matrix obtained from \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments for the two-search marked states \(\left| 101\right\rangle\) and \(\left| 110\right\rangle\), executed with 7797 repeated shots in a noisy environment, (d) and 1024 repeated shots on ibm_osaka, yielding \(\mathcal {F}_S\) of 80.8501% and 49.2329%, respectively. (d) Re.\((\rho )\) and Im.\((\rho )\) parts of the density matrix obtained from \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments for the two-search marked states \(\left| 111\right\rangle\) and \(\left| 101\right\rangle\), executed with 7797 repeated shots in a noisy environment, (e) and 1024 repeated shots on ibm_osaka, yielding \(\mathcal {F}_S\) of 83.7605% and 68.9419%, respectively.

Analysis and discussions

In this section, following the collection of experimental data, we performed a comprehensive statistical analysis. Our aim was to derive meaningful conclusions regarding the performance of the GSA across various settings, focusing on aspects such as \({\mathcal {ASP}}\), \({\mathcal {SSO}}\), state fidelity \(\mathcal {F}_S\), and to assess the influence of noise and other factors on its effectiveness.

\({\mathcal {ASP}}\) analysis

The statistical tests conducted offer critical insights into the \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) of a 3-qubit GSA executed on IBM Quantum’s real quantum computers, particularly in estimating the population of all 2-marked states oracles within the 3-qubit space (see Tables 3 and 4). The mean \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) of 64.44% provides a central measure of the algorithm’s performance in identifying desired states within the quantum system, while the standard deviation of 16.67 offers an indication of the variability in \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) values around the mean. The subsequent one-sample t-test comparing the observed mean \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) against a hypothesized population mean yields a non-significant p-value of 0.99, indicating that the observed mean \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) is likely representative of the population mean. This suggests that the algorithm’s performance, as observed on IBM Quantum’s real quantum computers, aligns closely with theoretical expectations or benchmark values. Similarly, the hypothesis test for variance, with a p-value of 0.868, suggests no significant difference in the variability of \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) between the observed sample and the hypothetical population. Thus, the variability in \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) observed in the sample is deemed consistent with that of the population. Overall, these results underscore the reliability and validity of the observed \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) values in estimating the population of 2-marked states within the 3-qubit space.

\({\mathcal {SSO}}\) analysis

The statistical tests conducted on the \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) for a 3-qubit GSA executed on IBM Quantum’s real quantum computers provide reliable insights into estimating population parameters for all 2-marked states oracles within the 3-qubit space (see Table 3 and 4). The mean \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) value of 63.10 represents the average squared statistical overlap between observed two-search result oracles, with a standard deviation of 17.07 indicating variability around this mean. A one-sample t-test with a 95% confidence interval (CI), yielding a non-significant p-value of 0.99, suggests that the observed mean \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) is representative of the population mean. Additionally, the 95% confidence intervals for variance offer insights into the precision of estimated variability within the population. The hypothesis test for variance, with a p-value of 0.867, indicates no significant difference in variability between the observed sample and the hypothetical population. These results underscore the accuracy and reliability of the observed \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) values in estimating population parameters.

Evaluation of state fidelity

We conducted a statistical analysis to assessing the reliability of the state fidelity measurement and providing insights into the variability of the fidelity of the GSA with different marked states and to examine the differences in algorithm performance across the three settings (as presented in Table 5), aiming to understand the fidelity of the population of all 3-qubit marked states.

The statistical tests on the state fidelity of a 3-qubit GSA executed on real quantum computers provide valuable insights into the fidelity of all 3-qubit marked states. The mean fidelity of 0.5432, with a standard deviation of 0.099, reflects both the average fidelity and its variability across experiments. The one-sample t-test with a 95% CI (0.4205, 0.6661) compares the observed mean fidelity against a hypothesized population mean. The resulting p-value of 1.00 indicates that there is insufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis, implying that the observed mean fidelity is not significantly different from the hypothesized population mean. This suggests that the observed mean fidelity is likely representative of the population. Similarly, the hypothesis test for variance, yielding a p-value of 0.812, suggests no significant difference in variability between the observed sample and the hypothetical population.

This reinforces the reliability of the observed sample’s representation of the population and underscores the consistency in fidelity across different experiments. These tests provide confidence in the accuracy and reliability of the observed \(\mathcal {F}_S\) values, aiding in understanding the fidelity of the population of all 3-qubit marked states.

Quantum hardware

Algorithm performance

The performance of the GSA across different environments is depicted in Figure 6 and Figure 7. Figure 6 illustrates the performance of the GSA across all 3-qubit single-marked states (\(\left| 000\right\rangle , \, \left| 001\right\rangle\), \(\left| 010\right\rangle , \, \left| 011\right\rangle\), \(\left| 100\right\rangle , \, \left| 101\right\rangle\), \(\left| 110\right\rangle , \, \text {and} \left| 111\right\rangle\)) across different environments: noise-free, noisy, and IBM Quantum’s quantum hardware. While Figure 7 showcases the performance for the nine 3-qubit two-marked states ( \(\left| 000\right\rangle -\, \left| 111\right\rangle\), \(\left| 001\right\rangle -\, \left| 100\right\rangle\), \(\left| 011\right\rangle -\, \left| 100\right\rangle\), \(\left| 010\right\rangle -\, \left| 111\right\rangle\), \(\left| 000\right\rangle -\, \left| 110\right\rangle\), \(\left| 010\right\rangle -\, \left| 101\right\rangle\), \(\left| 101\right\rangle -\, \left| 110\right\rangle\), \(\left| 101\right\rangle -\, \left| 111\right\rangle\), and \(\left| 100\right\rangle -\, \left| 111\right\rangle\)), evaluating their performance across different environments: noise-free, noisy, and real quantum hardware.

GSA performance across all 3-qubit single-marked states (\(\left| 000\right\rangle , \, \left| 001\right\rangle\), \(\left| 010\right\rangle , \, \left| 011\right\rangle\), \(\left| 100\right\rangle , \, \left| 101\right\rangle\), \(\left| 110\right\rangle , \, \text {and} \left| 111\right\rangle\)) across different environments: noise-free, noisy environment, and IBM Quantum’s quantum hardware.

GSA performance for the nine 3-qubit two-marked states (\(\left| 000\right\rangle -\, \left| 111\right\rangle\), \(\left| 001\right\rangle -\, \left| 100\right\rangle\), \(\left| 011\right\rangle -\, \left| 100\right\rangle\), \(\left| 010\right\rangle -\, \left| 111\right\rangle\), \(\left| 000\right\rangle -\, \left| 110\right\rangle\), \(\left| 010\right\rangle -\, \left| 101\right\rangle\), \(\left| 101\right\rangle -\, \left| 110\right\rangle\), \(\left| 101\right\rangle -\, \left| 111\right\rangle\), and \(\left| 100\right\rangle -\, \left| 111\right\rangle\)) across different environments: noise-free, noisy environment, and IBM Quantum’s quantum hardware.

Hardware specifications

In this section, we provide a summary of key specifications and qubit characteristics for three state-of-the-art 127-qubit superconducting quantum computers utilized in our experimental endeavors within this research. These cutting-edge quantum machines, developed by IBM Quantum, namely: ibm_sherbrook, ibm_osaka, and ibm_kyoto. Table 6 presents the specifications of ibm_sherbrook, including its model, basis gates, processor type, median ECR error, and CLOPS. The processor type is Eagle r3, and the quantum system exhibits a median ECR error of \(7.565 \times 10^{-3}\), with 5000 CLOPS. While Table 7 and 8 provide a detailed summary of the essential specifications and qubit characteristics for the 127-qubit quantum computers. ibm_osaka and ibm_kyoto, respectively. Readout error map and layout of the ibm_sherbrooke quantum computer is shown in Figure 8.

Readout error map, qubit mapping, and layout of the ibm_sherbrooke quantum computer. This system is built on the Eagle r3 quantum processor, which comprises 127 superconducting transmon qubits. For detailed performance metrics, refer to Table 6.

It is important to emphasize that in Qiskit68,69, qubits are arranged in little-endian order, where the qubit with the smallest index corresponds to the least significant bit. For instance, in a three-qubit system, it is represented as \(|q_2q_1q_0\rangle\). Due to this convention, in practical implementations on IBM Quantum’s hardware, the circuits displayed will appear horizontally flipped compared to their usual depiction.

Conclusion

Quantum computers are poised at the cutting edge of technological progress, unlocking exponential computational speedups that push the boundaries of what classical computing can achieve. As quantum computing continues to evolve, Grover search algorithm stands as a pivotal advancement in the field of quantum computing, offering a revolutionary approach to solving unstructured search problems. This algorithm addresses a fundamental challenge in computing–finding a desired item in an unsorted database significantly faster than classical methods allow. Its importance cannot be overstated, as it promises exponential speedup over classical algorithms for a wide range of applications, from cryptography to database search and optimization.

Our comprehensive study sheds light on the practical implementation and performance evaluation of GSA on a state-of-the-art 127-qubits superconducting quantum computers. Through our exploration of single-solution and two-solution scenarios, we have uncovered both promising capabilities and significant challenges. Despite the presence of noise, the algorithm demonstrated a remarkable ability to maintain a high \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) and \({\mathcal {SSO}}\). For instance, in single-solution scenarios, we observed an average \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) of 78.39% and an average \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) of 82.358%, and in two-solution scenarios, an average \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) of 84.44% and an average \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) of 84.03%. However, executing the algorithm on real superconducting quantum computers revealed practical constraints, leading to decreased \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) and \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) metrics. Specifically, we noted an average \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) of 51.19% and an average \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) of 73.12% in single-solution scenarios, and an average \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) of 64.44% and an average \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) of 63.10% in two-solution scenarios.

Furthermore, our statistical analyses, which included one-sample t-tests and 95% confidence intervals, provided robust insights into the consistency and reliability of the performance metrics we observed. The one-sample t-tests comparing the observed mean \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) and \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) against hypothesized population means yielded non-significant p-values, indicating that the observed means of \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) and \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) are statistically representative of the population means in both scenarios. Similarly, hypothesis tests for variance produced p-values of 0.868 and 0.867, suggesting that there is no significant difference in the variability of \({\mathcal {ASP}}\) and \({\mathcal {SSO}}\) between our observed sample and the hypothetical population.

Additionally, we conducted five \({\mathcal {QST}}\) experiments on IBM Quantum’s 127-qubits superconducting quantum computer, ibm_osaka, to assess the fidelity of output states in both single-search and two-search scenarios of the GSA. Our experiments using \({\mathcal {QST}}\) provided strong confidence in the fidelity of output states. Statistical tests on the state fidelity (\(\mathcal {F}_S\)) of a 3-qubit GSA executed on real quantum computers revealed a mean \({\mathcal {F}}_{\mathcal {S}}\) of 0.5432. A one-sample t-test with a 95% confidence interval (0.4205, 0.6661) comparing the observed mean state fidelity against a hypothesized population mean yielded a non-significant p-value, indicating the observed state fidelity is likely representative of the population, with no significant variance observed, suggesting no significant difference in variability between the observed sample and the hypothetical population, reinforcing the reliability and consistency of fidelity across experiments.

Grover’s algorithm represents a monumental breakthrough in quantum computing, redefining our ability to solve unstructured search problems with unparalleled efficiency. By enabling faster discovery of a target within an unsorted database, it not only challenges the classical limits but also opens the door to transformative advancements in fields like cryptography, optimization, and large-scale data analysis. By addressing practical challenges such as noise and environmental disturbances, we can further enhance the scalability and applicability of quantum algorithms in real-world settings. Our research endeavored to contribute to the ongoing efforts to bridge the gap between theoretical developments and practical implementations, paving the way for transformative applications across various domains.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are included within this article.

References

Huang, H. Y. et al. Quantum advantage in learning from experiments. Science 376, 6598 (2022).

Yin, J. et al. Entanglement-based secure quantum cryptography over 1,120 kilometres. Nature 582, 501–505 (2020).

Ebadi, S. et al. Quantum Optimization of Maximum Independent Set using Rydberg Atom Arrays. Science 376, 1209 (2022).

Alvarez-Rodriguez, U. et al. Quantum Artificial Life in an IBM Quantum Computer. Sci. Rep. 8, 14793 (2018).

Gircha, A. I. et al. Hybrid quantum-classical machine learning for generative chemistry and drug design. Sci. Rep. 13, 8250 (2023).

Chen, Y. A. et al. An integrated space-to-ground quantum communication network over 4,600 kilometres. Nature 589, 214–219 (2021).

AbuGhanem, M. Photonic quantum computers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.08229 (2024).

AbuGhanem, M. & Eleuch, H. NISQ computers: A path to quantum supremacy. IEEE Access 12, 102941–102961 (2024).

Bernstein, E., Vazirani, U. Quantum complexity theory, in: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC’93), pp 11-20 (1993).

Simon, D. R. On the power of quantum computation. SIAM J. Comput. 26, 1411–1473 (1997).

Shor, P. W. Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring, in: Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, IEEE, pp 124-134 (1994).

Harrow, A. W., Hassidim, A. & Lloyd, S. Quantum algorithm for linear systems of equations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103(15), 150502 (2009).

Cerezo, M. et al. Variational quantum algorithms. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3(9), 625–644 (2021).

Peruzzo, A. et al. A variational eigenvalue solver on a photonic quantum processor. Nat. Commun. 5(1), 4213 (2014).

Farhi, E., Goldstone, J. & Gutmann, S. A quantum approximate optimization algorithm. arXiv 1411, 4028 (2014).

AbuGhanem, M. Information processing at the speed of light. Front. Optoelectron. 17, 33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12200-024-00133-3 (2024).

Grover, L. K. Quantum mechanics helps in searching for a needle in a haystack. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 325–328 (1997).

Boyer, M., Brassard, G., Høyer, P. & Tapp, A. Tight bounds on quantum searching. Fortschr. Phys. 46, 493–505 (1998).

Bennett, C., Bernstein, E., Brassard, G. & Vazirani, U. Strengths and weaknesses of quantum computing. SIAM J. Comput. 26, 1510–1523 (1997).

Magniez, F., Santha, M. & Szeged, M. Quantum algorithms for the triangle problem. SIAM J. Comput. 37, 413–424 (2007).

Durr, C., Heiligman, M., Høyer, P. & Mhalla, M. Quantum query complexity of some graph problems. SIAM J. Comput. 35, 1310–1328 (2006).

Ramesh, H. & Vinay, V. String matching in \({\tilde{O}}(\sqrt{n}+\sqrt{m})\) quantum time. J. Discrete Algorithms 1(1), 103–110 (2003).

Christoph, D., & Peter, H. A quantum algorithm for finding the minimum. arXiv: quant-ph/9607014 (1996).

Andris, A., & Nikita, L. Quantum algorithms for computational geometry problems. In: 15th Conference on the Theory of Quantum Computation, Communication and Cryptography. 9: 1-10 (2020).

Ambainis, A., Balodis, K., Iraids, J., et al. Quantum speedups for exponential-time dynamic programming algorithms, in: Proceedings of the 13th Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms. San Diego: SIAM, pp 1783-1793 (2019).

Chuang, I. L., Gershenfeld, N. & Kubinec, M. Experimental implementation of fast quantum searching. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 3408–3411 (1998).

Bhattacharya, N., van Linden van den Heuvell, H. B., & Spreeuw, R. J. C. Implementation of quantum search algorithmusing classical Fourier optics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 137901 (2002).

Brickman, K.-A. et al. Implementation of Grover’s quantum search algorithm in a scalable system. Phys. Rev. A 72, 050306(R) (2005).

Walther, P. et al. Experimental one-way quantum computing. Nature 434, 169–176 (2005).

DiCarlo, L. et al. Demonstration of two-qubit algorithms with a superconducting quantum processor. Nature 460, 240–244 (2009).

Barz, S. et al. Demonstration of blind quantum computing. Science 335, 303–308 (2012).

Mølmer, K., Isenhower, L. & Saffman, M. Efficient Grover search with Rydberg blockade. J. Phys. B: Atomic, Mol. Opt. Phys. 44(18), 184016 (2011).

Vandersypen, L. M. K. et al. Implementation of a three-quantum-bit search algorithm. Appl. Phys. Lett. 76, 646–648 (2000).

Figgatt, C. et al. Complete 3-Qubit Grover search on a programmable quantum computer. Nat. Commun. 8, 1918 (2017).

Lubinski, T. et al. Application-oriented performance benchmarks for quantum computing (IEEE Trans, Quantum Eng, 2023).

Roy, T. et al. Programmable superconducting processor with native three-qubit gates. Phys. Rev. Appl. 14, 014072 (2020).

Park, G., Zhang, K., Yu, K. & Korepin, V. Quantum multi-programming for Grover’s search. Quant. Inf. Proc. 22, 54 (2023).

Zhang, K. et al. Implementation of efficient quantum search algorithms on NISQ computers. Quant. Inf. Proc. 20, 1–27 (2021).

Zhang, K., Yu, K. & Korepin, V. Quantum search on noisy intermediate-scale quantum devices. Europhys. Lett. 140(1), 18002 (2022).

Pokharel, B. & Lidar, D. A. Better-than-classical Grover search via quantum error detection and suppression. Quant. Inf. 10(1), 23 (2024).

Wang, Y. & Krstic, P. S. Prospect of using Grover’s search in the noisy-intermediate-scale quantum-computer era. Phys. Rev. A 102(4), 042609 (2020).

Rao, P. et al. Quantum amplitude estimation algorithms on IBM quantum devices. Quantum Communications and Quantum Imaging XVIII. 11507. SPIE, (2020).

Rao, P., Yu, K., Lim, H., Jin, D. & Choi, D. Quantum multi-programming for Grover’s search. Quant. Inf. Proc. 22(1), 54 (2023).

Mandviwalla, A., Ohshiro, K., & Ji, B. Implementing Grover’s algorithm on the IBM quantum computers. 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data). IEEE, (2018).

Coles, P. J. et al. Quantum algorithm implementations for beginners. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.03719, (2018).

Kim, V. et al. Evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault tolerance. Nature 618, 500–505 (2023).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum computation and quantum information. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, \(10^{th}\) anniversary ed., (2011).

Maslov, D. Advantages of using relative-phase Toffoli gates with an application to multiple control Toffoli optimization. Phys. Rev. A 93, 022311 (2016).

AbuGhanem, M., A Toffoli gate decomposition via echoed cross-resonance gates. In preparation (2024).

ECR Gtae, IBM Quantum Documentation, https://docs.quantum.ibm.com/api/qiskit/qiskit.circuit.library.ECRGateIBM Quantum, accessed September (2024).

Chiaverini, J. et al. Implementation of the semiclassical quantum fourier transform in a scalable system. Science 308, 997–1000 (2005).

IBM Quantum, https://quantum.ibm.com/, accessed June (2024).

AbuGhanem, M. & Eleuch, H. Full quantum tomography study of Google’s Sycamore gate on IBM’s quantum computers. EPJ Quant. Technol. 11(1), 36 (2024).

AbuGhanem, M., & Eleuch, H. Experimental characterization of Google’s Sycamore quantum AI on an IBM’s quantum computer, Elsevier. SSRN 4299338 (2023).

Ivanova-Rohling, V. N., Rohling, N. & Burkard, G. Optimal quantum state tomography with noisy gates. EPJ Quant. Technol. 10, 25 (2023).

James, D. F., Kwiat, P. G., Munro, W. J. & White, A. G. On the measurement of qubits. Phys. Rev. A 64, 052312 (2001).

Teo, Y. S. et al. Quantum-state reconstruction by maximizing likelihood and entropy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 020404 (2011).

Smolin, J. A., Gambetta, J. M. & Smith, G. Efficient method for computing the maximum-likelihood quantum state from measurements with additive Gaussian noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 070502 (2012).

Qi, B. et al. Adaptive quantum state tomography via linear regression estimation: Theory and two-qubit experiment. Quant. Inf. 3(1), 19 (2017).

Bolduc, E., Knee, G. C., Gauger, E. M. & Leach, J. Projected gradient descent algorithms for quantum state tomography. Quant. Inf. 3(1), 44 (2017).

AbuGhanem, M. & Eleuch, H. Two-qubit entangling gates for superconducting quantum computers. Results Phys. 56, 107236 (2024).

Volya, D., Nikitin, A., & Mishra, P. Fast quantum process tomography via Riemannian gradient descent. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.18840 (2024).

AbuGhanem, M., et al. Fast universal entangling gate for superconducting quantum computers, Elsevier. SSRN, 4726035 (2024). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4726035.

AbuGhanem, M. Full quantum process tomography of a universal entangling gate on an IBM’s quantum computer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.06946 (2024).

Zhukov, A. A. et al. Quantum communication protocols as a benchmark for programmable quantum computers. Quant. Inf. Process. 18, 31 (2019).

Liao, C. T., Bahrani, S., da Silva, F. F. & Kashefi, E. Benchmarking of quantum protocols. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 5298 (2022).

Jozsa, R. Fidelity for Mixed Quantum States. J. Mod. Opt. 41, 2315–2323 (1994).

Javadi-Abhari, A. et al. Quantum computing with Qiskit. arXive preprint arXiv:2405.08810 (2024).

AbuGhanem, M. IBM quantum computers: Evolution, performance, and future directions, arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.00916 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the use of IBM Quantum’s superconducting quantum computers in this research. Nevertheless, the perspectives and findings presented in this paper are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of IBM Quantum. M. AbuGhanem extends special thanks to Prof. Diego Emilio Serrano (Panasonic Massachusetts Laboratory) and Frank Harkins (IBM Quantum developer advocacy) for providing assistance in questioning regarding retrieving extensive experimental results.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). Open access publishing under the agreement between Springer Nature and STDF in cooperation with Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). The author declares that no funding, grants, or other forms of support were received at any point throughout this research work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. AbuGhanem: conceptualization, methodology, quantum programming, experimental implementations on IBM Quantum’s quantum computers, data curation, formal analysis, statistical analysis, visualization, investigation, validation, writing, reviewing and editing. The author has approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval and Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

AbuGhanem, M. Characterizing Grover search algorithm on large-scale superconducting quantum computers. Sci Rep 15, 1281 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80188-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80188-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Demonstration of measurement-free universal logical quantum computation

Nature Communications (2026)

-

Efficient implementation of a quantum algorithm with a trapped ion qudit

Nature Communications (2026)

-

Toward scalable fault-tolerant photonic quantum computers

The Journal of Supercomputing (2026)

-

IBM quantum computers: evolution, performance, and future directions

The Journal of Supercomputing (2025)

-

Coherent wave-particle quantum walks

Quantum Information Processing (2025)