Abstract

Social adjustment is critical to preschool children’s overall development and well-being. Household chaos and emotion regulation are important influencing factors that affect young children’s social adjustment. Our study examines the interplay between household chaos and social adjustment among preschool children and investigates the mediating function of emotion regulation. Three parent report scales with sufficient reliability and validity were completed by parents from six kindergartens: the Confusion, Hubbub and Order Scale (CHAOS), Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC), and Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation (SCBE-30). The results showed that household chaos can directly and indirectly predict social adjustment via the intermediary effect of emotion regulation. Understanding and addressing household chaos, as well as supporting children in developing emotion regulation skills, can play a significant role in promoting social adjustment and mental health in preschool children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Social adjustment is critical to children’s overall development and well-being. A socially well-adjusted child is more likely to be happy, have better self-esteem, and form strong relationships with others1,2. Additionally, child social adjustment is associated with improved academic performance and fewer behavioral problems3. Household chaos is an important environmental factor that influences children’s social development4. Chaotic households can have a negative impact on children’s development, including health issues5, behavioral issues6, poor academic performance, and a lack of social skills7. Another determinant related to the social adjustment of young children is children’s emotion regulation. Emotion regulation in children is crucial for their social adjustment3, mental health8, and academic success9. When children are able to manage their emotions effectively, they are more likely to form positive relationships with others and cope with social challenges.

Household chaos and emotion regulation are important factors that affect children’s social adjustment. Our study seeks to investigate the association between household chaos and the social adjustment of preschool children. Moreover, the effect of household chaos on social adjustment is explored by testing emotion regulation as a potential mediating variable. The meditating role of emotion regulation is underpinned by the presumption that developing children’s emotion regulation is typically optimized in home environments that are calm, predictable, and supportive. Our study adds to the body of literature concerning the link between household chaos and the social adjustment of young children and attempts to pinpoint the mediating function of emotion regulation, which has been overlooked by other studies. Furthermore, our study can shed light on prevention efforts and intervention programs designed to enhance the mental health, well-being and success of children facing challenging home environments.

Literature review

Household chaos and child development

Household chaos is an important factor of the family environment that can significantly affect children’s development and well-being. Chaotic households are characterized by noise, crowding, and a lack of routine and order10. Studies have shown that household chaos is associated with a range of negative outcomes for children. Children who grow up in chaotic homes may experience heightened levels of stress and anxiety, making it difficult for them to regulate their emotions and behaviors effectively and leading to problems in school and social settings, as well as poorer outcomes in terms of mental health and well-being7. Chaotic households have been linked with a diverse range of negative childhood outcomes, including poorer social and emotional development, executive functions11, and behavior problems6; even when controlling for socioeconomic status, adverse outcomes remain12. Studies have shown that children living in chaotic households exhibit more externalizing behaviors, which, when presented as early as the toddler and preschool years, are a risk factor for later maladjustment6.

Research has also shown that household chaos is associated with adverse effects on children’s physical development, such as increased weight status, poor sleep, and poor dietary behaviors. A study of 385 parents of children aged 2–5 years old revealed that household chaos can increase screen usage and behaviors that interfere with sleep at night, suggesting that it may be a risk factor for obesity in preschoolers13.

In addition to the direct effect of household chaos on children’s development, other studies have shown that household chaos mediates the associations between different variables and children’s development. For example, prior studies have revealed that household chaos can serve as a mediator between child behavioral issues and bedtime resistance14, as well as poverty and socioemotional adjustment difficulties15.

Emotion regulation and child development

The preschool period is a dynamic stage during which emotion regulation skills develop. Social and emotional competencies are becoming increasingly recognized and valued as essential for children’s school and life success. The growing body of literature on children’s emotion regulation concludes that emotion regulation is a sufficient factor for predicting child outcomes. Emotion regulation is crucial for fostering 2–6-year-old children’s adaptability to the novel demands of school environments16.

Research has demonstrated that emotion regulation is strongly associated with positive developmental outcomes, such as social competence17and plays a pivotal role in clinical conditions, such as externalizing problems and anxiety18. A study of 331 preschool children attending Head Start revealed that preschool children with lower emotion regulation exhibited difficulties in peer play19. A longitudinal study demonstrated that after controlling for depression, age, and gender, emotion dysregulation may serve as a potential risk factor for the development of anxiety among children20.

Emotion regulation refers to how individuals react to, handle, and adjust their emotional experiences to attain personal objectives and adapt to environmental demands21. The ability to effectively self-regulate emotional impulses and behaviors becomes increasingly important throughout preschool children’s development, facilitating adaptive psychological functioning throughout the lifespan22. The ability of children to regulate their emotions plays a crucial role in maintaining and even enhancing their psychological well-being.

Household chaos, emotion regulation, and social adjustment of children

Definitions of social adjustment have differed among various studies and researchers. In the current literature, social adjustment is typically characterized by the extent to which children successfully interact with their peers, demonstrate adaptive and competent social behaviors, and refrain from exhibiting aversive or incompetent conduct23. Children’s development is widely understood to result from interpersonal and intrapersonal factors. Among interpersonal factors, household chaos is an important factor in explaining children’s social development.

Household chaos is characterized by high levels of background stimulation, a lack of family routines, and an absence of predictability and structure in daily activities9. Wachs and Evans described household chaos as an environment with high levels of noise, crowding, and instability, along with an absence of temporal and physical structuring (e.g., limited regularities, routines, or rituals), resulting in a lack of defined times or places for activities15.

Well-developed emotion regulation is crucial for children’s school readiness and success later in life. Emotion regulation is an important component of emotional intelligence. Ulrich and Petermann defined emotion regulation as “a person’s ability to influence his or her own emotions in terms of quality, intensity, frequency, and their timing and expression, according to his or her own goals”24.

Based on the above relevant research, our study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1

Household chaos is closely negatively related to the social adjustment of preschool children.

H2

Emotion regulation is a positive predictor of social adjustment in preschool children.

H3

Emotion regulation serves as a mediator in the correlation between household chaos and social adjustment in preschool children.

Methodology

Sample

All four- to six-year-old children and their families were recruited from six kindergartens in Jinzhou, China. The researchers contacted the principals of nine public kindergartens that have established cooperative relationships with our college in Jinzhou and explained the aims of our research, and six of them agreed to participate in our study. The parents and children who participated in our study were all from these six kindergartens. The researchers used a simple random sampling method to select individuals from all six kindergartens. All population members have an equal probability of being selected, which tends to produce representative, unbiased samples25. The researchers took a multichannel approach to distribute the questionnaires online and in person, depending on the preferences and accessibility of our target respondents, to ensure the validity and reliability of our findings. For the offline questionnaires, the researchers asked parents to complete the questionnaires in person while waiting to pick up their children. For the online questionnaires, we requested the assistance of teachers to email the questionnaire to parents, and the available primary caregivers were asked to complete the questionnaires.

Out of the 800 participants, 673 completed the entire questionnaire, which is 84.13% of the total. The respondents consisted of 332 boys (49.33%) and 341 girls (50.67%) distributed among three-year-olds (31.65%), four-year-olds (33.58%), and five-year-olds (34.77%). With respect to family role, 69.99% of respondents were mothers, and 30.01% were fathers. Descriptive statistics for categorical data are shown in Table 1.

Procedure

The study was conducted from September 2023 to December 2023. Before participation, we explicitly outlined the purpose of the questionnaire to all participants and reassured them of the confidentiality of their responses by providing them with a detailed verbal explanation of the research objectives and relevant information to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the project. Parental informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from parents or legal guardians prior to the study. All the respondents participated in the study voluntarily and provided written consent to their voluntary agreement to participate. The study adherence to ethical regulations in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and subsequent amendments.

The participants were asked to complete three scales: CHAOS designed by Matheny26, ERC developed by Shields and Cicchetti27, and SCBE-30 scales designed by Lafreniere and Dumas28. They were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time if they were uncomfortable. Furthermore, they were advised that they had the right to decline to answer any specific question and that their anonymity would be strictly maintained in any ensuring publication. Stringent measures were taken to safeguard their identity. After completing the questionnaire, the participants provided their email address if they desired to receive a summary of the study’s findings. These procedures ensured the validity and reliability of the collected data and upheld the participants’ privacy and rights.

Measures

Confusion, Hubbub and Order Scale (CHAOS): Zhao and Liu developed the Chinese version of CHAOS, which was designed by Matheny, and tested its applicability to Chinese culture. The scale comprises three dimensions: confusion (5 items, e.g., “My family is very noisy”), hubbub (5 items, e.g., “It seems that my family members are always in a hurry”), and order (5 items, e.g., “From early morning on, our life is very regular”). It consists of 15 items, including measurements of environmental confusion and disorganization in the family. The respondents were instructed to respond to a 5-point Likert scale, with numbers 1–5 indicating “not true at all” to “true all the time.” The higher the score is, the quieter, more orderly, and less chaotic the family is. The internal consistency coefficient for the CHAOS scale was 0.86. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to test the model fit, and the fit indices met the criteria (RMSEA = 0.036, GFI = 0.96, IFI = 0.95, CFI = 0.96, RFI = 0.95, NFI = 0.96). The average variance extracted (AVE) values for confusion, hubbub, and order were 0.55, 0.63 and 0.51, respectively, and the composite reliability (CR) values for confusion, hubbub, and order were 0.86, 0.89, and 0.84, respectively. CR values of 0.7 or higher denote good reliability, and the AVE should not be lower than 0.5 to demonstrate an acceptable level of convergent validity29. According to Fornell and Larcker’s study30, the scale exhibits adequate discriminant validity because the absolute value of the correlation coefficient is less than 0.5 and is less than the square root of the corresponding AVE. As shown in Table 2, the CHAOS scale has adequate discriminant validity.

Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC): ERC which was developed by Shields and Cicchetti, is a scale often used to assess children’s emotion regulation ability. It has been widely adopted by scholars from various countries. In our study, the revised Chinese version by Zhu Jingjing et al. was employed. The revised ERC better aligns with the actual situation of young Chinese children. The original scale had 24 items, and confirmatory factor analysis revealed three items with factor loadings less than 0.3. The Chinese version of the ERC has 21 items with two dimensions: emotion regulation (8 items, e.g., “When adults show a neutral or friendly attitude toward my child, he or she respond positively”) and emotional lability/negativity (13 items, e.g., “My child is prone to becoming angry or losing his or her temper easily”). The questionnaire uses a four-point scoring system ranging from 1 to 4, representing “completely disagree” to “completely agree,” respectively. The higher the score on the scale is, the better the ability to regulate emotions. The overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of REC is 0.91, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for emotion regulation and emotional lability/negativity are 0.89 and 0.94, respectively. Confirmatory factor analysis revealed that the fit indices of the questionnaire are relatively ideal, with χ²/df = 2.23, CFI = 0.91, GFI = 0.91, IFI = 0.88, and RMSEA = 0.05. The composite reliability (CR) values for emotion regulation and emotional lability/negativity were 0.51 and 0.54 respectively, and the average variance extracted (AVE) values for emotion regulation and emotional lability/negativity were 0.89 and 0.93, respectively. As demonstrated in Table 3, the two dimensions of the ERC scale are significantly correlated with each other, and the absolute value of the correlation coefficient is much less than the square root of the corresponding AVE, indicating adequate discriminant validity.

Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation (SCBE-30): This scale was designed by Lafreniere and Dumas, and the Chinese version was revised by Liang Zongbao et al. The revised scale consists of 30 items with three dimensions: anxiety–shyness, anger–aggression, and sensitivity–cooperation. The scale uses a 6-point Likert scoring method, with 1 representing “never” and 6 representing “always.” The higher the score on the scale is, the better the degree of social adjustment. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the subscales range from 0.91 to 0.93, indicating good internal consistency reliability. The fit indices are χ2/df = 2.48, NFI = 0.87, GFI = 0.88, CFI = 0.92, and RMSEA = 0.06. Overall, the questionnaire demonstrates good reliability and validity. The composite reliability (CR) values for anxiety–shyness, anger–aggression, and sensitivity–cooperation were 0.92, 0.91, and 0.93, respectively, and the average variance extracted (AVE) values for anxiety–shyness, anger–aggression, and sensitivity–cooperation were 0.54, 0.53 and 0.59, respectively. As presented in Table 4, the three dimensions of the Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation scale are significantly correlated; however, the absolute value of the correlation coefficient is substantially lower than the square root of the respective AVE, demonstrating adequate discriminant validity.

Data analyses

Because the data in our study were self-reported by fathers and mothers separately, common method bias may exist. Our study used Harman’s single-factor test to detect common method bias31,32. Despite discussions about the effectiveness of Harman’s single factor test33,34, it is currently the most commonly used method for verifying the common bias problem35. The results revealed that 12 factors had eigenvalues greater than 1 for all the items, and the first factor explained 20.38% of the variance, which is far less than the critical value of 40%31. Thus, there was no significant common method bias in our study.

The associations between household chaos (Confusion, Hubbub and Order), emotion regulation (emotion regulation and emotional lability/negativity), and social adjustment (anxiety–shyness, anger–aggression, and sensitivity–cooperation) were tested via correlation analysis. However, to gain a deeper understanding, we conducted a bootstrap mediation analysis to determine whether emotion regulation acts as a mediator in the association between household chaos and social adjustment.

Results

Correlation analyses

The means and standard deviations of all the variables are shown in Table 5, along with the correlation coefficients of all the variables. As shown in Table 5, the results of the correlation analyses revealed a significant association between household chaos, emotion regulation, and social adjustment in the preschool child population. The correlation coefficients between household chaos, emotion regulation, and social adjustment are − 0.44 (p < 0.01) and − 0.57 (p < 0.01), respectively. Additionally, the correlation coefficient between emotion regulation and social adjustment is 0.49 (p < 0.01). To gain a deeper understanding of the relationship between household chaos and social adjustment, further investigations into the mediating role of emotion regulation are advised.

Mediation analyses

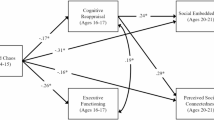

To further investigate the mediating effect of emotion regulation in various dimensions of household chaos on young children’s social adaptation, the bootstrap method proposed by Preacher and Hayes was utilized36. The Preacher and Hayes approach for assessing mediation suggests a two-step process using the bootstrapping method. First, the indirect effect (or total effect) of the mediating variable (emotion regulation) on the dependent variable (social adjustment) via the independent variable (household chaos) is estimated through bootstrapping. The association between household chaos and social adjustment through emotion regulation should be significant, typically indicated by a p value less than 0.05. Second, the lower level (LL) and upper level (UL) of the bootstrapping confidence interval are determined. The confidence interval provides an estimation of the range of plausible values for the mediating effect. Our study constructed a structural equation for measuring the household chaos, emotion regulation, and social adjustment of preschool children. The fit indices are χ2/df = 1.98, NFI = 0.97, GFI = 0.98, CFI = 0.96, and RMSEA = 0.04, indicating that the model has good adaptability.

Table 6 shows the relationships among the household chaos, emotion regulation, and social adjustment in preschool children. According to the regression weight results, household chaos has a significant effect on the social adjustment of preschool children, and the standardized regression coefficient indicates that household chaos has a negative effect on social adjustment (β=−0.64, p < 0.01). Similarly, it can be concluded that household chaos negatively impacts emotion regulation (β=−0.67, p < 0.01). However, regression analysis revealed that emotion regulation has a positive effect on the social adjustment of preschool children (β = 0.27, p < 0.01).

The direct effect of household chaos on the social adjustment of preschool children was − 0.64, with a confidence interval of −0.82 to −0.45 (77.92% of the total effect), indicating a significant negative direct effect, as shown in Table 7. Regarding the indirect effect, the significance of the indirect effect of household chaos through emotion regulation was confirmed by the results of the nonparametric bootstrapping method (95% bootstrap CI=−0.32, −0.05), which accounted for 22.19% of the total effect. Simultaneously, the total effect of household chaos on social adjustment was − 0.82, with a confidence interval of −0.89 to −0.75, indicating a significant total effect. These results indicate that household chaos not only significantly negatively impacts social adjustment but also affects it indirectly through the mediation of emotion regulation (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Our study examines the interplay between household chaos and social adjustment among preschool children and the mediating function of emotion regulation. Correlational analysis revealed a noteworthy association between household chaos, emotion regulation, and social adjustment. Furthermore, the results of the mediation analysis indicate that emotion regulation has direct and indirect mediating effects on the effect of household chaos on preschool children’s social adjustment. The findings of our research support Hypotheses H1, H2, and H3.

First, the findings of our study showed that household chaos can significantly predict young children’s social adjustment, confirming H1. Household chaos, which is characterized by disorganization, overcrowding, excessive noise, a lack of routine, and unpredictable daily activities, has been associated with various physical, emotional, and functional issues in children. In chaotic households, caregivers may be preoccupied with managing the chaos, leaving less time and energy for nurturing and bonding with children, making it difficult for them to build secure attachments with parents and others14. Similarly, a chaotic household disrupt children’s ability to focus and communicate with others, impeding social development37. Household chaos has a detrimental effect on children’s social adjustment.

Second, the findings of our study supported H2 by showing that emotion regulation had a favorable effect on preschool children’s social adjustment, which is consistent with earlier studies16,20. In preschool-aged children, effective emotion regulation skills are crucial for successful social adjustment. Research has shown that children with better emotion regulation skills tend to make more social adjustments22. When children can regulate their emotions, they are better equipped to handle challenging social situations, enabling them to respond more appropriately to social cues, resolve conflicts, and maintain positive relationships with peers and teachers38. They are more likely to engage in positive social behaviors, such as sharing, cooperating, and helping others. They are also more likely to have stronger social skills, such as communication, perspective taking, and empathy39. These skills are essential for successful social interactions and relationships. Emotion regulation plays a vital role in preschool children’s social adjustment and lays the foundation for successful social functioning throughout childhood and beyond.

Finally, the findings of our study support H3 by demonstrating that emotion regulation serves as a significant mediating factor between household chaos and the social adjustment of preschool children. A chaotic household often increases stress levels for both parents and children, impairing children’s ability to regulate their emotions effectively4. Chaotic households can disrupt children’s sleep patterns, further impacting their emotion regulation abilities due to fatigue and irritability14. Good emotion regulation is protective against mental health issues such as anxiety and depression, which can interfere with social adjustment40. Effective emotion regulation enhances social adjustment, allowing children to navigate social situations confidently and adaptively.

In summary, household chaos negatively impacts the emotion regulation abilities of preschool children by increasing stress7, limiting emotional support11, and disturbing sleep patterns14. In turn, emotion regulation plays a crucial role in shaping children’s social adjustment, as it influences their interpersonal relationships19, social competence17, and mental health20. By addressing household chaos and fostering healthy emotion regulation skills, parents and educators can help children develop adaptability, which they need to thrive socially.

Implications

This study contributes to the literature concerning the multifaceted factors of preschool children’s social development. While previous research has focused primarily on factors such as parenting styles, family socioeconomic status, and preschool education, the current study explores the nexus between household chaos and children’s social adjustment, with emotion regulation serving as a mediator. The theoretical implications of our research underscore the complexity of early childhood development and the need for comprehensive, multifaceted approaches to support children’s social adjustment. By illuminating the mechanisms linking household chaos, emotion regulation, and social adjustment, our research provides a valuable framework for future research and intervention efforts to facilitate positive outcomes for all children. Our research underscores the interconnectedness of different areas of development and the need for holistic approaches to intervention and support.

Additionally, our study provides practical implications for parents and educators concerning the potential impact of household chaos on children’s social adjustment, encouraging efforts to reduce household chaos, and creating more conducive environments for child development. Moreover, emotion regulation mediates the relationship between household chaos and social adjustment, suggesting that interventions aimed at enhancing emotion regulation skills may be effective in reducing the negative effects of household noise. Educational programs can incorporate strategies for enhancing emotion regulation skills to help children better adapt to a chaotic family environment24. Early childhood is a pivotal phase in the development of children’s emotion regulation, during which they transition from relying heavily on external regulation from caregivers to gradually gaining the ability to exert more deliberate control over their emotional experiences41. Caregivers play a key role in cultivating the development of emotion regulation through the processes by which they provide external support or scaffolding as children navigate their emotional experiences42.

Limitations and future directions

Our study provides valuable guidance for both educational theory and practice, yet it is not without its limitations or shortcomings. First, the participants in our study were exclusively from six kindergartens in China. Although this has little influence on the study results, it may limit the generalizability of the research findings to other countries and regions. It would be intriguing to explore the validity of the findings in further studies in other kindergartens or population groups. Second, our study utilized a cross-sectional approach to establish the relationship between household chaos, emotion regulation, and social adjustment in preschool children. Although we used a standard approach for conducting an initial assessment of novel associations6, a cross-sectional study cannot establish causation, as all the data were collected at a single time via self-report questionnaires. As a consequence, longitudinal research is encouraged to strengthen the understanding of the causal relationships among household chaos, emotion regulation, and social adjustment among preschool children. In addition to household chaos and emotion regulation, the social adjustment of preschool children is the result of the combined effects of various personal and social factors. These factors include personal factors such as personality43, social-emotional competencies44and social factors such as teacher–child relationships45and economic status46. Discussing all these factors in a single study is challenging because of their diverse theoretical constructs and methodologies. It is necessary to explore these factors in greater depth and provide a more thorough understanding of the associations among household chaos, emotion regulation, and social adjustment in preschool children. Notably, our study relied on parental reports, which are subjective, to gather data on young children’s social development. Future research should incorporate teachers’ evaluations as an additional means of objectively assessing young children’s social development.

Conclusion

Our study investigated how household chaos influences social adjustment and the mediating effect of emotion regulation. Early childhood is a critical period for children’s social development. However, some children exhibit social incompetence or behavioral issues that hinder healthy social interactions47. We expect that our study will highlight the need to consider the importance of household chaos in child well-being research, particularly in families where children may be more vulnerable to the adverse effects of household chaos. Emotion regulation is pivotal for achieving success in social interactions and academic pursuits, particularly in school24. Household chaos can negatively impact emotion regulation, which then hinders social adjustment. Understanding and addressing household chaos, as well as supporting children in developing emotion regulation skills, can play a significant role in promoting the social adjustment and mental health of preschool children.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Omoponle, A. Social adjustment, a necessity among students with negative body-image: the roles of parenting processes and self esteem. J. Cult. Values Educ. 6 (3), 62–80. https://doi.org/10.46303/jcve.2023.20 (2023).

Wu, Q., Zhao, J., Zhao, G., Du, H. F. & Chi, P. L. Affective profiles and psychosocial qdjustment among Chinese adolescents and adults with adverse childhood experiences: a person-centered approach. J. Happiness Stud. 23, 3909–3927. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00566-7 (2022).

DeRosier, M. E. & Lloyd, S. W. The impact of children’s social adjustment on academic outcomes. Read. Writ. Q. 7 (1–2), 25–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2011.532710 (2010).

Martin, A., Razza, R. A. & Brooks-Gunn, J. S. Specifying the links between household chaos and preschool children’s development. Early Child. Dev. Care. 182 (10), 1247–1263. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2011.605522 (2012).

Wirth, A. et al. Examining the relationship between children’s ADHD symptomatology and inadequate parenting: the role of household chaos. J. Atten. Disord. 23 (5), 451–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054717692881 (2019).

Larsen, K. L. & Jordan, S. S. Organized chaos: Daily routines Link household chaos and child behavior problems. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 29, 1094–1107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01645-9 (2020).

Marsh, S., Dobson, R. & Maddison, R. The relationship between household chaos and child, parent, and family outcomes: a systematic scoping review. BMC Public. Health. 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08587-8 (2020).

Lennarz, H. K., Hollenstein, T., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., Kuntsche, E. & Granic, I. Emotion regulation in action: use, selection, and success of emotion regulation in adolescents’ daily lives. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 43 (1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025418755540 (2019).

Edossa, A. K., Schroeders, U., Weinert, S. & Artelt, C. The development of emotional and behavioral self-regulation and their effects on academic achievement in childhood. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 42 (2), 192–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025416687412 (2018).

Wachs, T. D. & Evans, G. W. Chaos in context. In Evans, G. W. & Wachs, T. D. Chaos and its influence on children’s development: An ecological perspective. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/12057-001 (2010).

Andrews, K., Atkinson, L., Harris, M. & Gonzalez, A. Examining the effects of household chaos on child executive functions: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 147 (1), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000311 (2021).

Dumas, J. E. et al. Home chaos: sociodemographic, parenting, interactional, and child correlates. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 34 (1), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_9 (2005).

Emond, J. A., Tantum, L. K. & Gilbert-Diamond, D. Household chaos and screen media use among preschool-aged children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 18, 1210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6113-2 (2018).

Boles, R. E. et al. Family chaos and child functioning in relation to sleep problems among children at risk for obesity. Behav. Sleep. Med. 15 (2), 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2015.1104687(2017).

Evans, G. & Wachs, T. Chaos and its influence on children’s development: An ecological perspective. American Psychological Association. 448. https://doi.org/10.1037/12057-000 (2010).

Ellie, M., Harrington, S. D., Trevino, S. L. & Nicole, R. G. Emotion regulation in early childhood: implications for socioemotional and academic components of school readiness. Emotion. 20 (1), 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000667 (2020).

Contreras, J. M., Kerns, K. A., Weimer, B. L., Gentzler, A. L. & Tomich, P. L. Emotion regulation as a mediator of associations between mother–child attachment and peer relationships in middle childhood. J. Fam. Psychol. 14, 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.14.1.111 (2020).

Brumariu, L. E., Kerns, K. A. & Seibert, A. C. Mother–child attachment, emotion regulation, and anxiety symptoms in middle childhood. Pers. Relatsh. 19, 569–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01379.x (2012).

Cohen, J. S., & Mendez, L. J. Emotion regulation language ability, and the stability of preschool children’s peer play behavior. Early Educ. Dev. 20 (6), 1016–1037. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280903305716 (2009).

Schneider, R. L., Arch, J. J., Landy, L. N. & Hankin, B. N. The longitudinal effect of emotion regulation strategies on anxiety levels in children and adolescents. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. 47 (6), 978–991. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1157757 (2018).

Thompson, R. A. Emotion regulation: a theme in search of definition. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child. Dev. 59 (2/3), 25–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/1166137 (1994).

Morrish, L., Rickard, N., Chin, T. C. & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. Emotion regulation in adolescent well-being and positive education. J. Happiness Stud. 19 (5), 1543–1564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9881-y (2017).

Spinrad, T. L. & Gal, D. E. Fostering prosocial behavior and empathy in young children. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 20, 40–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.08.004 (2018).

Thümmler, R., Engel, E. M. & Bartz, J. Strengthening emotional development and emotion regulation in childhood-As a key task in early childhood education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 (7), 3978. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073978 (2022).

Mitra, S. K. & Pathak, P. K. The nature of simple random sampling. Ann. Statist. 12 (4), 1536–1542. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176346810 (1984).

Adam, P. M., Theodore, D. W., Jennifer, L. L. & Kay, P. Bringing order out of chaos: psychometric characteristics of the confusion, hubbub, and order scale. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 3, 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/0193-3973(95)90028-4 (1995).

Shields, A. & Cicchetti, D. Emotion regulation among school age children: the development and validation of a new criterion q-sort scale. Dev. Psychol. 33 (6), 906–916. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.906 (1997).

Laferniere, P. J. & Dumas, J. E. Social competence and behavior evaluation in children ages 3 to 6 years: the short form (SCBE-30). Psychol. Assess. 8 (4), 369–377. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.8.4.369 (1996).

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J. & Anderson, R. E. Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice-Hall. 619 (2009).

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312 (1981).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88 (5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 (2003).

Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y. & Babin, B. J. Common methods variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 69 (8), 3192–3198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008 (2016).

Aguirre-Urreta, M. I. & Hu, J. Detecting common Mmthod Bbas: performance of the Harman’s single-factor test. ACM SIGMIS Database: DATABASE Adv. Inform. Syst. 50 (2), 45–70. https://doi.org/10.1145/3330472.3330477 (2019).

Howard, M. C., Boudreaux, M. & Oglesby, M. Can Harman’s single-factor test reliably distinguish between research designs? Not in published management studies. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psy August. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2024.2393462 (2024).

Kock, F., Berbekova, A. & Assaf, A. G. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: detection, prevention and control. Tour Manag. 86, 104330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104330 (2021).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. (2013).

Bobbitt, K. C. & Gershoff, E. T. Chaotic experiences and low-income children’s social-emotional development. Child. Youth Serv. Re. 70, 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.006 (2016).

Kirk, G. & Jay, J. Supporting kindergarten children’s social and emotional development: examining the synergetic role of environments, play, and relationships. J. Res. Child. Educ. 32 (4), 472–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2018.1495671 (2018).

Domitrovich, C. E., Durlak, J. A., Staley, K. C. & Weissberg, R. P. Social-emotional competence: an essential factor for promoting positive adjustment and reducing risk in school children. Child. Dev. 88 (2), 408–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12739 (2018).

Menefee, D. S., Ledoux, T. & Johnston, C. A. The importance of emotional regulation in mental health. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 16 (1), 28–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/15598276211049771 (2022).

Grabell, A. S. et al. Neural correlates of early deliberate emotion regulation: Young children’s responses to interpersonal scaffolding. Dev. Cogn. Neuros-Neth. 40, 100708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2019.100708 (2019).

Paley, B. & Hajal, N. J. Conceptualizing emotion regulation and coregulation as family-level phenomena. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 25, 19–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-022-00378-4 (2022).

Zhu, J., Fu, R., Li, Y., Wu, M. & Yang, T. Shyness and adjustment in early childhood in southeast China: The moderating role of conflict resolution skills. Front. Psychol. 12, 644652. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.644652 (2021).

Nakamichi, K., Nakamichi, N. & Nakazawa, J. Preschool social-emotional competencies predict school adjustment in Grade 1. Early Child. Dev. Care. 191 (2), 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2019.1608978 (2019).

Dong, Y., Wang, H., Luan, F., Li, Z. & Cheng, L. How children feel matters: teacher–student relationship as an indirect role between Interpersonal trust and social adjustment. Front. Psychol. 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.581235 (2021).

Henry, D. A., Betancur Cortés, L. & Votruba-Drzal, E. Black–white achievement gaps differ by family socioeconomic status from early childhood through early adolescence. J. Educ. Psychol. 112 (8), 1471–1489. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000439 (2020).

Colonnesi, C., Zeegers, M. A. J. & Majdandžić, M. Fathers’ and mothers’ early mind-mindedness predicts social competence and behavior problems in childhood. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 47, 1421–1435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-019-00537-2 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to show our great appreciation to the participants for their support and assistance in data collection.

Funding

This study is supported by the project “The Study on ‘Culture Education’ in Chinese Universities” (No. DIA220371) sponsored by National Office for Education Sciences Planning.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and writing, Qian Meng; formal analysis and data curation, Zimo Cai. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by Ethical Review Committees of Bohai University (No. BHU-2023-122). We certify that the study was performed in accordance with the 1964 declaration of HELSINKI and later amendments.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all the parents or legal guardians prior to the enrolment of this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, Z., Meng, Q. Household chaos, emotion regulation and social adjustment in preschool children. Sci Rep 14, 28875 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80383-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80383-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Cortisol Reactivity as a Moderator in the Relationship Between Home Chaos and Conduct Problems: Gender-Specific Evidence from Chinese Preschoolers

Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback (2025)