Abstract

Premature dropout from psychotherapy can harm patients and increase mental health costs. This study identified predictors of dropout in brief online psychotherapy for essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was a secondary analysis of a randomized trial on 4-week CBT or IPT protocols. Participants provided sociodemographic data and completed the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System and Burnout Assessment Tool Short-Form. Predictors were analyzed in three blocks: sociodemographic, clinical, and therapist characteristics using bivariable and multivariable analyses. The sample included 804 individuals who attended at least the first session of either CBT (n = 403) or IPT (n = 401). A total of 17.2% (n = 138) of the participants dropped out during the protocol. Significant predictors of dropout included having children (IRR = 1.48; 95% CI: 1.07–2.05; p = 0.016), residing in specific regions of Brazil (Northeast IRR = 1.44; 95% CI:1.04–2.00; p = 0.02 and Midwest IRR = 1.73; 95%CI: 1.13–2.64; p = 0.01), therapist male sex (IRR = 2.04; 95% CI: 1.47–2.83; p = < 0.001), second wave of Covid-19 (IRR = 1.54; 95% CI: 1.01–2.34; p = 0.04) and low life satisfaction (IRR = 1.63; 95% CI: 1.06–2.50; p = 0.02). Our findings underscore the necessity for culturally tailored strategies, support for those with children, and targeted therapy for individuals with low life satisfaction. Implementation of these strategies may reduce dropout rates and improve treatment outcomes for essential workers in crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infection caused by the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has evolved into a global public health crisis, profoundly affecting various segments of our society, including healthcare professionals (HCPs). Several studies conducted worldwide have highlighted an increase in mental distress among HCPs, characterized by high levels of anxiety, traumatic stress, sleep disturbances, and depression1,2,3. It is important to emphasize that deterioration in the mental health of healthcare professionals has been observed in other health emergencies, such as SARS and MERS infections4. These findings underscore the pressing need for interventions aimed at alleviating psychological distress, a concern that extends beyond frontline workers to encompass all facets of the healthcare system and other essential professionals1,3,5,6. Factors such as resource shortages, challenges in crisis management by authorities, and the proliferation of misinformation about the pandemic have compounded emotional distress, contributed to stigmatization, and heightened the risk of psychiatric disorders, particularly among healthcare professionals in low- and middle-income countries7.

In response to the mental health challenges faced by essential professionals during the pandemic, numerous remote psychological treatment programs have been developed8, such as the TECHS Program in the USA9, the TELEPSI in Brazil10, and the REST in France11. Additionally, Spain developed PsyCovidApp12, and there were online mindfulness programs in Canada13 and Japan14. These programs aim to address specific emotional problems and to bolster coping mechanisms among healthcare professionals. Digital interventions have become a viable option for mental health treatment due to their cost-effectiveness, with face-to-face and online therapies appearing equally effective in improving patient outcomes15. However, data on dropout rates are mixed; some studies show no difference between face-to-face and online therapy dropout rates16,17, while others indicate greater dropout in online therapy18,19. The main challenges with online therapy include individual preferences, symptom severity, and technological difficulties16. During the COVID-19 pandemic, online interventions became essential due to social isolation. A study assessing the attitudes of patients, students, and healthcare professionals toward digital health found that all groups had positive attitudes toward the use of eHealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the presence of depressive symptoms did not influence these attitudes20. Although certain symptoms are typically associated with higher dropout rates16, these data suggest an opposite trend in the context of online care. Understanding the reasons for dropout in this context is crucial, as the challenges encountered are not always the cause of abandonment. Therefore, it is essential to explore the factors influencing dropout rates to improve these interventions or to develop more effective interventions and support mechanisms, particularly in times of crisis.

Psychotherapy dropout occurs when a patient decides to end treatment before it is recommended or before experiencing improvement in their symptoms or the issue that led them to seek therapy21. While dropout is quite prevalent, with approximately one in five individuals abandoning psychotherapy before its conclusion21, some studies suggest that it can also occur due to symptom improvement, which is not necessarily a negative outcome22,23. Dropout can have far-reaching consequences, including the exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms, allocation challenges for clinical resources, and increased healthcare system costs24,25. A comprehensive meta-analysis with over 80,000 patients revealed a dropout rate of 19.7% across different therapeutic approaches21. Factors such as younger age, receiving treatment at a university-based clinic, having a personality disorder, severity of symptoms, and lower education levels were associated with higher rates of treatment discontinuation21,26,27. Among these, age has been strongly associated with treatment dropout. Both, younger and older age has been identified as a predictor of dropout in digital interventions for individuals with depressive symptoms and chronic pain28. Therefore, age may serve as a meaningful marker for enhancing engagement in mental health interventions21. Furthermore, the literature reveals mixed findings concerning between psychiatric symptoms and dropout; while some studies indicate that dropout may occur as symptoms improve22,23, others link dropout to lack of improvement or even symptom worsening21,22. Thus, contradictory results on the associations of dropouts of the studied factors need to be understood for their implications on treatment retention.

While many studies assessing interventions for healthcare professionals have focused on efficacy, effectiveness, applicability, symptom improvement, or comparisons between face-to-face and online psychotherapy11,29,30, none have specifically investigated the predictors of dropout from brief treatment within a sample of professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overburdened healthcare professionals, beyond facing significant impacts on their mental health and the healthcare system, may experience low work motivation and reduced productivity, leading to suboptimal patient care31. Studies evaluating longer psychotherapy protocols via telepsychotherapy compared to face-to-face treatment have shown that patient characteristics, treatment credibility, and therapeutic alliances can influence dropout rates21,28,32.

The present study highlights the need to understand the factors linked to dropout in a brief psychotherapy protocol adapted for a time of crisis, which is usually associated with increased rates of mental illness. Given the significant mental distress experienced by professionals during this period, it is crucial to understand the underlying reasons for therapy abandonment beyond the therapeutic approach itself.

Therefore, our objective was to analyze which factors are associated with dropout during an online 4-week brief psychotherapy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or interpersonal therapy (IPT) delivered to essential professionals within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on previously described findings18,21,22,26,33,34, our hypothesis is that symptom severity, such as higher levels of depression, anxiety, and irritability, increases the likelihood of dropout. Additionally, we hypothesize that younger patient age is associated with a higher risk of dropout, and we do not expect differences in dropout rates between the two treatment modalities (CBT and IPT).

Method

Design

In this paper, we conducted a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical35 trial that aimed to evaluate the efficacy of telepsychotherapy (CBT or IPT) for the treatment of emotional problems in essential professionals during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, with a specific focus on identifying predictors of treatment dropout. We considered dropout when a participant was absent on the scheduled day and time and did not respond to three contact attempts made by the team (via email or telephone), or when they informed the team spontaneously that they would no longer participate before completing the protocol after having attended at least the first session.

Participants were individuals who contacted the Audible Response Unit (URA) of the Brazilian Ministry of Health or accessed the website (https://telepsi.hcpa.edu.br/) seeking psychological support for mental health issues related to the emotional stress of the pandemic between May 2020 and December 2021. The TELEPSI35 project was promoted through the internet, television, and institutional emails (from health services in the public assistance network). The project was advertised as a free mental health telecare service for essential professionals working during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the aim of helping these individuals cope with stress, anxiety, depression, and irritability caused by the stressful crisis, with different modalities of psychotherapy. The present study evaluated data from participants who received at least one session of brief cognitive-behavioral therapy or brief interpersonal therapy. We did not include individuals who did not attend the first session (non-attendance) because (a) we aimed to study factors related to the therapist or to the patient dyad that can influence dropout; and (b) we understood that dropout and non-attendance are different concepts26.

Ethics statement

This study is in accordance with the Guidelines and Norms Regulating Research Involving Human Beings (Resolution No. 466/12), following the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital de Clinicas de Porto Alegre (2020 − 0213), and the trial was registered in (CAAE: 30608420.5.0000.5327) and ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04635618; November 17, 2020)]. All individuals included in the study read and signed the informed consent form before the start.

Sample

Our sample comprises a total of 804 individuals who attended at least the first session of the CBT or the IPT protocol. The eligibility criteria for participants in this sample were as follows: (a) adults, who were essential service professionals, such as healthcare professionals and teachers (this second category received treatment for a shorter period than the total duration of the study), (b) expressed interest in receiving mental health care through the project’s website or phone, (c) signed the informed consent form, and (d) had a T-score of 70 or higher on the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) subscales of anxiety, depression, or irritability, and d) attended at least the first session of the 4-week IPT or CBT protocol. The exclusion criteria were (a) inability to respond to questionnaires, (b) risk of suicide requiring immediate evaluation in an emergency service, and (c) scheduled for treatment, but not attending the first session. All individuals who expressed their interest in the project were contacted and provided with the informed consent form, which they signed prior to proceeding. Following the consent process, participants were asked to complete online questionnaires. Participants knew that they would be treated for their emotional problems with an online psychotherapy for 4 weeks, but they did not know, at any point during enrollment, what type of intervention they would receive; therefore, there was no patient preference for one or another treatment modality.

In the present study, because our aim was to evaluate dropout rates and our inclusion criterion was participation in at least one session, we included only those individuals who were randomly assigned to receive either IPT or CBT. Other treatment arms (the control group) that did not include weekly telepsychotherapy sessions were not included in our sample.

Measures

We used the following instruments to evaluate the clinical characteristics of the sample and the severity of symptoms:

-

Sociodemographic Data Questionnaire: This instrument was developed by researchers to collect comprehensive sociodemographic information. It includes questions about sex, age, occupation, workplace, presence of children, alcohol and drug use, physical activity, and COVID-19-related information. The questionnaire was designed to collect relevant demographic and behavioral data relevant to study objectives.

-

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)36,37: We utilized the depression, anxiety, irritability, quality of sleep and life satisfaction subscales of the PROMIS scale. The PROMIS is a self-administered scale developed by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), consisting of 8 screening items for depressive symptoms, 8 screening items for anxiety symptoms, 5 screening items for irritability, 8 screening items for sleep quality, and 5 screening items for life satisfaction. Participants responded to these items using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. The higher the score is, the greater the presence of symptoms. These scales are indicated for individuals aged 18 years or older. The psychometric properties of the adapted version showed adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha coefficients: 0.70–0.80), validity and reliability, providing their applicability to the Brazilian context.

To evaluate burnout, we used the following:

-

The Burnout Assessment Tool Short-Form (BAT): This is a self-administered scale consisting of 12 items. It was created to measure burnout and its primary symptoms of exhaustion, decline in emotional self-regulation, decline in cognitive self-regulation and mental detachment. Participants responded to these items using a Likert scale ranging from “never” to “always,” with response options assigned values ranging from 1 to 5. We used the translated and adapted BAT-12 version to the Brazilian38,39. Its validity and measurement invariance were investigated and were globally satisfactory with good psychometric properties.

Intervention

All interventions were conducted online in the TELEPSI project35. The CBT protocol consisted of weekly CBT sessions over a period of 4 weeks. The first session focused on establishing a therapeutic alliance, identifying mental health problems, and reviewing the results of the forms completed by the participants in the application. The second session addressed psychoeducation on the cognitive model and emotions and introduced mindfulness and diaphragmatic breathing techniques. The third session focused on cognitive flexibility and addressed the stigma experienced by healthcare professionals during the pandemic. The final session involved reviewing self-regulation strategies, promoting behavioral activation, working on problem solving and acceptance, and discussing relapse prevention.

The IPT protocol also consisted of weekly sessions over a period of four weeks. The first session focused on establishing a therapeutic alliance, preparing the interpersonal inventory and defining the problem area. Sessions 2 and 3 focused on addressing the specific problem area identified in the first session, with an emphasis on strategies related to role transition, grief, and interpersonal disputes. The final session aimed to manage feelings associated with ending therapy, review the progress made, and discuss relapse prevention.

In both protocols, psychoeducation videos related to the specific topics discussed in the sessions were sent to the participants between each session. All sessions were conducted individually, lasted 50 min and were recorded with the participant’s consent. These sessions were held by videoconferencing software and were accessed through individual passwords.

Psychotherapists

Psychotherapists were trained psychologists or psychiatrists selected through a competitive process based on their experience with mental health assistance, involvement in research projects related to IPT or CBT treatment, and hours of technical training in these psychotherapy modalities Fourteen selected therapists underwent protocol training and were assigned to either CBT or IPT groups based on their area of expertise. The imminent emergency caused by COVID-19 required quick and efficient training for these professionals by the research team to meet the demand. After completing the training, all the therapists underwent an evaluation before starting the treatment sessions. Additionally, some sessions were observed and evaluated by the group supervisor to ensure adherence to treatment protocols. Throughout the entire duration of the project, all the therapists had weekly supervision with senior psychotherapists to discuss the cases.

Procedures

The participants were contacted after completing the online questionnaires and were randomly assigned to either the CBT or IPT treatment group. The allocation of therapists was also random. Therapists had a maximum of one week to schedule the session after receiving the patient’s referral. The psychotherapeutic team then contacted the participants through phone or email and scheduled the therapy sessions based on their availability.

The protocol was designed to be completed within 4 weeks. If a participant missed a session and contacted the assigned therapist, the session was rescheduled. However, the protocol could not be extended beyond 6 weeks. When the therapist had difficulty scheduling appointments with the participant, they were transferred to another professional with a better schedule availability. If the individual became infected with COVID-19 and was unable to carry out the sessions, they resumed as soon as they recovered. As described before, dropout was defined after attending the first session as follows: when a participant was absent on the scheduled day and time and did not respond to three contact attempts made by the team (via email or telephone), or when they informed the team spontaneously that they would no longer participate before completing the protocol. Participants who needed to interrupt the therapy protocol due to the severity of their symptoms were referred to telepsychiatry and were excluded from the analyses.

It is important to note that participants did not register for a specific type of therapy, but rather for brief therapy sessions via video calls aimed at alleviating emotional distress or preventing mental health problems among frontline healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. They were also informed that the therapy would consist of four sessions. All these details were included in the informed consent form.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the statistical software SPSS version 29. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample. Group comparisons were conducted using chi-square tests and Student’s t tests. The normality of the sample was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

The assessment of predictors of dropout was conducted using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEEs) with a Poisson distribution and robust variances to estimate the incidence rate ratio and a 95% confidence interval. We first performed our analysis using continuous measures and then categorized age and PROMIS scores into tertiles to standardize the measures across variables for the final model. The analysis with age and PROMIS scores as continuous variables provides the same consistent results, confirming that categorization into tertiles did not affect the final interpretation of our findings (see Table S1 in Supplementary Material). The dependent variable was treatment dropout, defined as the participant unilaterally giving up participation before completing the protocol. The selection of potential dropout predictor variables was based on meta-analysis studies by Gersh et al., (2017), Cooper & Conklin, (2015) and Fernandez et al., (2015). The independent variables, representing the potential predictive factors, were categorized into blocks:

-

1.

Sociodemographic data included sex (male or female), age, presence of children (yes or no), region of residence (South, North, Northeast, Southeast, Midwest), professional category (administrative, nurses, doctors, technicians, multidisciplinary or education), therapy group (CBT or IPT) and wave of COVID-19 (first wave or second wave). These professionals were classified into six groups: nurses (including nurses, nursing technicians, and assistants), doctors, multidisciplinary (professionals who work together to ensure integrated and personalized patient care - including psychologists, nutritionists, physiotherapists, social workers, biomedics, speech therapists, and dentists), technicians and other groups (including nutrition technicians, radiology technicians, laboratory technicians, students, paramedics, health drivers, and health agents), administrative teams (individuals working in the administrative area of hospitals), and education professionals (including teachers and school directors).

-

2.

Clinical characteristics included suicide risk, subscales of depression, anxiety, irritability, sleep disturbance, burnout, and life satisfaction.

-

3.

Therapist characteristics included the sex of the therapist, age of the therapist and number of training hours before engaging in the TELEPSI project.

The analysis was conducted in two stages. First, a bivariable analysis was performed for each block individually to identify the variables that were statistically associated with treatment dropout. A significance level of p < 0.1 was adopted for this stage. Only the variables that met this criterion were included in the subsequent hierarchical analysis.

We selected specific reference categories based on their representation within the sample, including the South region, the second wave of COVID-19, age 45 or older, nursing team profession, CBT as the treatment type, and the lowest-scoring categories on the PROMIS scale. We categorized the COVID-19 wave periods based on the number of infections and deaths provided by the Brazilian government register (https://covid.saude.gov.br/). The first wave was identified as occurring from May to November 2020, followed by a stabilization period. The second wave started in December 202039. This second wave period was associated with the new variants and continued until the end of the project in December 2021, although most participants in this wave were included in the first semester of the year 2021.These variables are denoted with a value of 1 in the tables. The only scale with an inverted interpretation, where a higher score indicated better outcomes, was the PROMIS life satisfaction scale.

Afterward, we performed a multivariable analysis and considered only the variables that had a significant level of p < 0.05 at the final level of the model as relevant dropouts. Values of > 1 in the incidence rate ratio (IRR) indicated a greater likelihood of treatment dropout.

The sample size calculation was originally performed for the clinical trial itself. In the clinical trial, an alpha of 0.017 (comparisons between the three groups, 0.05 / 3), power of 90%, with 1:1:1 randomization and differences in response rate of more than 15% between groups, required 279 individuals per group35. With a 20% loss to follow-up, approximately 1,000 subjects would need to be randomized for the original trial35.

Results

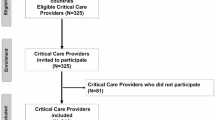

The whole sample consisted of 804 healthcare professionals, teachers, and essential service workers who attended at least the first session of CBT or IPT from the treatment protocol. Most of the participants were females with children, who were employed by the nursing team, aged between 26 and 35 years, and residing in the Southeastern region of the country. We had a total of 17.2% (n = 138) dropout. The flowchart (Fig. 1) illustrates the dropout numbers during the psychotherapy sessions in each group. Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of the sample characteristics, comparing those who dropped out and those who completed treatment. We also present sample characteristics according to the treatment group (CBT and IPT) in Table S2 in the Supplementary Material. These columns reported the percentage of individuals in each characteristic. In addition, the table includes a “Comparisons between concluded X dropout” column that provides the results of chi-squared tests for categorical variables and Student’s t-tests for continuous variables characteristics. This initial analysis of factors associated with dropout and completion rates in different treatment modalities highlights significant differences and provides preliminary insights into characteristics that may influence treatment outcomes (see Supplementary Table S2).

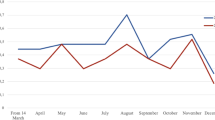

The greatest number of psychotherapeutic sessions occurred during the second wave of the pandemic in Brazil, from November 2020 to November 2021. When comparing those who dropped out with those who completed the protocol, we identified statistically significant differences in variables such as age (being young), having children, and professional status as described in Table 1. Additionally, differences in clinical and therapist characteristics between the groups are presented in Table 1. Each therapist treated an average of 57 participants, with those treating fewer than 20 participants not remaining in the project for more than a few months. The number of sessions conducted by each therapist is detailed in Supplementary Table S4.

We first performed a bivariable analysis to identify the different variables (sociodemographic, therapist and clinical characteristics) associated with dropout in the whole sample followed by a multivariable analysis.

Bivariable analysis

The statistically significant variables for dropout in the initial bivariable analysis were: having children and region of residence, with the Northeast and Midwest indicating a greater likelihood of treatment interruption compared to the South. The second wave of the pandemic also contributed to a greater risk of dropout. On the other hand, being a medical doctor was associated with a lower likelihood of dropout. Patient’s age and sex, and type of treatment were not significantly associated with dropout. This data is available in Table 2. Separate analyses by treatment group are available in Table S3 in the Supplementary Material.

There was no statistically significant association with the presence or severity of depressive or anxious symptoms, irritability, or burnout. However, individuals with a score above 33 points on the PROMIS scale of sleep were more prone to dropout at any point in the protocol. Lower scores on the life satisfaction scale (< 20) were associated with a greater likelihood of dropping out than were scores greater than 21 (see Table 2).

Of the 14 therapists who participated in the study, the majority were female (n = 11) and had an average age between 30 and 40 years. The only characteristic associated with dropout among therapists was sex, with male therapists (n = 3) having a greater likelihood of dropping out than to female therapists. The results of the entire bivariable analysis can be seen in Table 2.

Multivariable analysis

At the first level, we included the sociodemographic variables that were significant (p < 0.10) in the bivariable analysis and found that receiving sessions during the second wave of COVID-19, having children and region were significantly associated with a greater likelihood of dropout. The professional category lost its significance at the first level of analysis and did not enter the subsequent level of analysis (Administrative: IRR = 0.77, CI95%(0.47–1.26), p = 0.30; Multidisciplinary: IRR = 0.98, CI95% (0.67–1.43), p = 0.91; Technicians: IRR = 0.89, CI95%(0.70–1.15), p = 0.39; Doctors: IRR = 0.36, CI95%(0.09–1.39), p = 0.13; Education: IRR = 0.73, CI95%(0.37–1.44), p = 0.37).

At the second level, we retained these sociodemographic variables and included the variables from the block of clinical characteristics that were statistically significant in the bivariable analysis (life satisfaction and sleep disturbance). As described in the Method section, here we considered variables with p < 0.05. The sleep scale was excluded, as it did not remain significant (Scores 28–32: IRR = 1.17, CI95%(0.81–1.70), p = 0.39; Scores of 33 or more: IRR = 1.21, CI95%(0.90–1.62), p = 0.19). The third block included therapist characteristics, in this analysis gender remained significant for treatment dropout.

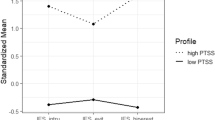

The final model with factors related to dropout is presented in Table 2. These differences are also illustrated in Fig. 2.

Discussion

Our study aimed to evaluate the factors associated with dropout in a sample of essential professionals (teachers and healthcare workers) who received brief online therapy (CBT or IPT) during the COVID-19 pandemic. The main results showed that: (1) having children, (2) living in certain regions of Brazil, (3) having sessions during the second wave of COVID-19, (4) being treated by a male therapist, and (5) having lower scores on the life satisfaction scale were associated with dropout.

Approximately 17.2% (n = 138) of our sample dropped out of the treatment, which is consistent with the literature, indicating a range of variation between 17% and 41% 21,25,33,40,41,42. When examining studies that focus exclusively on online psychotherapies, the dropout rates remain within the same range16,18. A previous Brazilian study evaluated dropout rates in a brief therapy protocol for individuals with major depressive disorder and reported a high dropout rate (41.9%), associated with factors such as socioeconomic class, race, having children, poor social support and depressive symptoms40. It is important to note that their intervention consisted of 14-face-to-face sessions, whereas ours consisted of only 4-online sessions. It should be noted that our protocol for crisis management was ultra-brief and, although the dropout rate is in line with most studies, we expected an even lower rate for the short period of time and for the mental health crisis that followed the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dropout is not always negative, as it can sometimes occur due to symptom improvement22,23. Our analysis did not show an association between baseline symptom scores and dropout, which was our initial hypothesis. Different studies on dropout have shown that the severity of symptoms can be a determining factor for abandonment16,21,26. However, a study on digital health also found that depressive symptoms did not influence attitudes toward using this resource during the COVID-19 pandemic, in agreement to our findings20. In addition, because we evaluated symptom scores only at baseline and not post intervention, we cannot definitively determine whether dropout was associated with symptom improvement.

The type of therapy was not significant in the bivariable analysis and was not included in our final model. Although the type of therapy is sometimes considered a factor influencing outcomes27, some studies suggest that it is not decisive for dropout33,34. Our findings align with this finding, as neither CBT or IPT were related to dropout rates; therefore, our data support the recent findings in the literature that a specific therapeutic approach does not significantly impact dropout21,27,33,34. Since participants were unaware of the type of intervention they would receive at registration, it is unlikely that they had preference, and thus, treatment modality did not affect dropout. These data highlight the debate between specific and nonspecific factors influencing psychotherapy outcomes43,44. We found no difference in technique, i.e., specific factors, but some unevaluated nonspecific factors, such as therapeutic alliance and empathy, might help us understand dropout in this context.

Our analysis revealed that having children increased the likelihood of treatment dropout by 1.48 times compared to those without children, which can be explained by factors such as task accumulation and lack of social support. Previous studies have shown that multitasking and lack of social support are significant stressors, particularly during periods of pandemic isolation40,45. Despite a recent meta-analysis finding that being young and female were risk factors for experiencing a wide range of psychiatric symptoms during the pandemic, these characteristics are also associated with dropout46. This suggests that the combined stressors of childcare responsibilities, social isolation, being young, and being female can contribute to a greater likelihood of treatment dropout due to increased psychological burden and fewer resources available to cope with these demands. Our sample was predominantly composed of females, who could be especially affected by these characteristics and multiple task activities could explain our findings.

An interesting and relevant finding from our study is the influence of the country’s region as a predictive factor for treatment dropout. We found a greater likelihood of abandonment in the Northeast (1.44 times more) and Midwest (1.73 times more) Regions in comparison to Southern, whereas most therapists were from the Southern Region of the country. Brazil has a rich cultural diversity resulting from different colonizations and immigration that are part of the country’s history, despite everyone speaking the same language. The Northeast and Midwest regions of Brazil have unique historical and cultural backgrounds, influenced by different patterns of colonization and different climates. For example, the Northeast, characterized by a semi-arid climate, has a higher prevalence of socioeconomic challenges, while the South benefits from a more temperate climate and a European-influenced cultural heritage, which may contribute to different levels of access to mental health resources and support systems. Data from the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted these differences. The evolution of the pandemic was different, starting in the north, followed by the northeast and the southern region was the last to progress with an increase in cases. In the same line, vaccination was faster in the South and Southeast, which also contributed to the reduction in mortality47. Regarding economic backgrounds, there are big disparities of the Gross Domestic Product (GPD) among regions. For instance: Rio Grande do Sul (South) reported a GDP of 581,284 million BRL, far surpassing that of Paraíba (Northeast) at 77,470 million BRL and Mato Grosso do Sul (Midwest) at 142,204 million BRL48. These economic differences may influence access to education, health and mental health services and support systems across regions. Besides that, working in psychotherapy with individuals from different cultures can be challenging, as it requires considering accents, expressions, religion, and the social context in which the individual is situated. Several studies emphasize the importance of considering the patient’s cultural background context during the psychotherapy process and the need for technical adaptations that take culture into account to achieve treatment success49,50,51,52. Therapists with multicultural competencies tend to have more engaged patients and achieve better outcomes53. Consequently, we believe that cultural factors may have impacted the risk of treatment abandonment. In addition, the hospital that hosted the website and the project is an outstanding institution but is known mainly to our local region (south). Thus, knowing the institution’s background might also contribute to treatment compliance in the southern region.

Lower levels of life satisfaction (≤ 14) were associated with a 1.63 times greater likelihood of dropout compared to those who scored 21 or higher on the scale (see Table 2). During the pandemic, lower life satisfaction levels were linked to increased mental health problems54. Life satisfaction is often a key factor influencing an individual’s psychological resilience, which is their ability to cope with stressful situations55. Higher resilience in HCPs during the pandemic was associated with better management of the mental burden, resulting in lower levels of burnout, anxiety, and depression45. Studies indicate that healthcare professionals, regardless of whether they were on the frontline, reported lower life satisfaction and higher levels of stress, burnout, and demotivation due to stressful working conditions56,57,58. Additionally, many HCPs were often reluctant to seek mental health services during the pandemic due to the associated stigma, viewing mental health services as a sign of weakness and worrying about colleagues’ and supervisors’ perceptions59. These factors may help explain why lower levels of life satisfaction were associated with higher dropout rates.

Healthcare professionals in low and middle-income countries, such as Brazil, faced greater challenges during the pandemic due to a lack of protective equipment, limited access to COVID-19 tests and vaccines, and difficulties in population adherence to distancing measures7. These factors worsened their mental health1,7,45. A cohort study in Brazil found that essential professionals experienced elevated levels of anxiety, burnout, insomnia, and post-traumatic stress from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, largely due to uncertainty related to the virus. Anxiety levels initially decreased by the end of the first wave, which the authors attributed to an increased adaptation to the situation60. However, the second wave, beginning in December 2020 and continuing through January 2021 with the emergence of a new COVID-19 variant and preceding vaccine availability47, led to a resurgence of symptoms, with anxiety returning to initial high levels. This period saw a dramatic increase in cases and deaths, contributing to significant pressure on the healthcare system, which may have increased the demand for psychotherapy60. Nonetheless, the resulting workload likely made it difficult for these professionals to attend sessions regularly. Our study further revealed that during this second wave, health professionals were 1.54 times more likely to drop out of psychotherapy compared to the first wave, potentially due to heightened work demands, reduced social support, and, possibly, stigma associated with seeking mental health support.

Concerning therapist characteristics, we found that being male was associated with a greater likelihood of dropout (2.04 times more). Although these data may seem relevant, as they were statistically significant for dropout, we had only 3 male therapists, and most of the participants who were enrolled in the study were also female. Therefore, it is not possible to differentiate whether the predictor of dropout is related to sex, the matching of female patients with male therapists or to nonspecific factors of the therapist.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The first limitation is that this is a secondary analysis of an RCT that was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions, not the predictors of dropout. Although we selected predictor variables according to the literature, many studies have discussed the role of the nonspecific factors associated with therapeutic relationship in dropout25,61, however, unfortunately, our study lacks data on these measures. In addition, the baseline measurements were assessed before the first session within one week, but we did not have data on the exact number of days between the patient’s contact and the scheduling of the first session. Furthermore, we were unable to assess the reason for the dropout. The study did not analyze in detail the personal characteristics of therapists due to their homogeneous age distribution, and predominant regional origin. Notably, the disproportionately low representation of male therapists within the sample may introduce bias and constrain the generalizability of findings concerning therapist gender dynamics. Additionally, the level of education of the professionals was not evaluated, which has been reported in different research studies to potentially influence dropout21,41. Other factors such as race and social class which are relevant in low-and-middle income countries such as Brazil were not evaluated. Although our sample consisted of professionals in essential services, their backgrounds were diverse, with significantly different salaries. Furthermore, considering financial aspects, the pandemic varied across states. Unfortunately, we were unable to collect these data for inclusion in our analysis.

Strengths

This is the first study that examines predictors of dropout in a brief remote therapy protocol designed for a crisis, specifically targeting professionals in essential services. This aspect is particularly important mainly because therapy, even in the online format, still has barriers to overcome. Even studies on brief psychotherapy often involve a greater number of sessions than ours. Understanding dropout in this context of 4 sessions, considering dose-response, seems relevant given the impact of health emergencies on the mental health of essential services professionals4,62.

Our study has a large sample size and includes two different treatment modalities which allows us to study different predictors of dropout. One of the major contributions of this manuscript is the identification of regions as a predictor of dropout. Brazil is a continental country, with many economic disparities and differences in accessing mental health services among regions. Surprisingly, participants from less developed regions dropped out more frequently. This finding highlights the potential role of cultural influences, even within the same country, in therapeutic relationships. In brief psychotherapy processes, there may not be enough time to develop a solid therapeutic alliance. Therefore, this work sheds light on the relevance of cultural backgrounds in psychotherapies, considering not only the region in which people live, but also cultural diversity in a broader sense.

Conclusions

Our study also showed that the rates of dropout from online therapy were similar to those previously reported for in-person treatment. Thus, it could be more cost-effective and reach remote regions where there are few trained therapists available since it works for most patients. We identified several specific and important factors associated with dropout, such as: having children, having different cultural backgrounds, and having different types of therapist sex. On the other hand, higher scores on the life satisfaction scale were associated with a lower likelihood of discontinuing treatment. These findings are crucial for improving the delivery of online brief therapy during health crises, especially considering the unique challenges faced by essential service providers whose work can be impacted by mental health issues. Understanding and addressing dropouts in this context is essential for supporting professionals who play a vital role in maintaining societal functioning. As future perspectives, it is important to evaluate therapist factors, therapeutic alliances, patient beliefs and expectations, and sociocultural contexts to understand the phenomenon of psychotherapeutic dropout. Evaluating these data can be important for understanding their impact on developing future strategies for essential workers during crises.

Data availability

Data availability statement The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The primary study is currently under review for publication in the Lancet Regional Health.

References

García-Iglesias, J. J. et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) on the mental health of healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica. 94, e202007088 (2020).

Lee, B. E. C., Ling, M., Boyd, L., Olsson, C. & Sheen, J. The prevalence of probable mental health disorders among hospital healthcare workers during COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 330, 329–345 (2023).

Thatrimontrichai, A., Weber, D. J. & Apisarnthanarak, A. Mental health among healthcare personnel during COVID-19 in Asia: a systematic review. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 120, 1296–1304 (2021).

De Brier, N., Stroobants, S., Vandekerckhove, P. & De Buck, E. Factors affecting mental health of health care workers during coronavirus disease outbreaks (SARS, MERS & COVID-19): a rapid systematic review. PloS One. 15, e0244052 (2020).

Søvold, L. E. et al. Prioritizing the Mental Health and Well-Being of Healthcare Workers: an Urgent Global Public Health Priority. Front. Public. Health 9, (2021).

Vanhaecht, K. et al. COVID-19 is having a destructive impact on health-care workers’ mental well-being. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 33, mzaa158 (2021).

Deng, D. & Naslund, J. A. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Frontline Health Workers in low- and Middle-Income Countries. Harv. Public. Health Rev. Camb. Mass. 28, (2020). http://harvardpublichealthreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Deng-and-Naslund-2020-28.pdf

Kazantzis, N., Carper, M. M., McLean, C. P., Sprich, S. E. & Editorial Applications of cognitive and behavioural therapy in response to COVID-19. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 28, 455–458 (2021).

Price, J., Kassam-Adams, N. & Kazak, A. E. Toolkit for Emotional coping for Healthcare Staff (TECHS): Helping Healthcare workers cope with the demands of COVID-19. Del. J. Public. Health. 6, 10–13 (2020).

Salum, G. A. et al. Letter to the editor: training mental health professionals to provide support in brief telepsychotherapy and telepsychiatry for health workers in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J. Psychiatr Res. 131, 269–270 (2020).

Weiner, L. et al. Efficacy of an online cognitive behavioral therapy program developed for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: the REduction of STress (REST) study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 21, 870 (2020).

Serrano-Ripoll, M. J. et al. Effect of a mobile-based intervention on mental health in frontline healthcare workers against COVID-19: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. J. Adv. Nurs. 77, 2898–2907 (2021).

Kim, S., Crawford, J. & Hunter, S. Role of an online skill-based mindfulness program for Healthcare Worker’s Resiliency during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-method study. Front. Public. Health 10, (2022).

Miyoshi, T., Ida, H., Nishimura, Y., Ako, S. & Otsuka, F. Effects of yoga and Mindfulness Programs on Self-Compassion in Medical professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: an intervention study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 12523 (2022).

Etzelmueller, A. et al. Effects of Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in routine care for adults in treatment for depression and anxiety: systematic review and Meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e18100 (2020).

Lippke, S., Gao, L., Keller, F. M., Becker, P. & Dahmen, A. Adherence with Online Therapy vs Face-to-face Therapy and with online therapy vs Care as Usual: secondary analysis of two randomized controlled trials. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e31274 (2021).

Watson, H. J. et al. Predictors of dropout in face-to-face and internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa in a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 50, 569–577 (2017).

Fernandez, E., Salem, D., Swift, J. K. & Ramtahal, N. Meta-analysis of dropout from cognitive behavioral therapy: magnitude, timing, and moderators. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 83, 1108–1122 (2015).

Waller, R. & Gilbody, S. Barriers to the uptake of computerized cognitive behavioural therapy: a systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative evidence. Psychol. Med. 39, 705–712 (2009).

Giannouli, V. E-health before-and-during covid-19: does depressive symptomatology influence attitudes of cad patients, healthcare students and professionals? Psychiatr Danub. 35, 245–249 (2023).

Swift, J. K. & Greenberg, R. P. Premature discontinuation in adult psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 80, 547–559 (2012).

Larsen, S. E. et al. Symptom change prior to treatment discontinuation (dropout) from a naturalistic Veterans affairs evidence-based psychotherapy clinic for PTSD and depression. Psychol. Serv. 20, 831–838 (2023).

Simon, G. E., Imel, Z. E., Ludman, E. J. & Steinfeld, B. J. Is Dropout after a first psychotherapy visit always a bad outcome? Psychiatr Serv. Wash. DC. 63, 705–707 (2012).

Altmann, U. et al. Outpatient psychotherapy improves symptoms and reduces Health Care costs in regularly and prematurely terminated therapies. Front. Psychol. 9, (2018).

Gmeinwieser, S., Schneider, K. S., Bardo, M., Brockmeyer, T. & Hagmayer, Y. Risk for psychotherapy drop-out in survival analysis: the influence of general change mechanisms and symptom severity. J. Couns. Psychol. 67, 712–722 (2020).

Fenger, M., Mortensen, E. L., Poulsen, S. & Lau, M. No-shows, drop-outs and completers in psychotherapeutic treatment: demographic and clinical predictors in a large sample of non-psychotic patients. Nord J. Psychiatry. 65, 183–191 (2011).

Swift, J. K. & Greenberg, R. P. A treatment by disorder meta-analysis of dropout from psychotherapy. J. Psychother. Integr. 24, 193–207 (2014).

Moshe, I. et al. Predictors of Dropout in a Digital intervention for the Prevention and Treatment of Depression in patients with Chronic Back Pain: secondary analysis of two randomized controlled trials. J. Med. Internet Res. 24, e38261 (2022).

Amsalem, D. et al. Video intervention to increase treatment-seeking by healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry. 220, 14–20 (2022).

Hedman-Lagerlöf, E. et al. Therapist-supported internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy yields similar effects as face-to-face therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 22, 305–314 (2023).

Amsalem, D. et al. Brief video intervention to Increase Treatment-Seeking Intention among U.S. Health Care Workers: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychiatr Serv. Wash. DC. 74, 119–126 (2023).

Alfonsson, S., Olsson, E. & Hursti, T. Motivation and treatment credibility predicts Dropout, Treatment Adherence, and clinical outcomes in an internet-based cognitive behavioral relaxation program: a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 18, e5352 (2016).

Gersh, E. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of dropout rates in individual psychotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 52, 25–33 (2017).

Cooper, A. A. & Conklin, L. R. Dropout from individual psychotherapy for major depression: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 40, 57–65 (2015).

Salum, G. A. et al. Brief remote psychological treatments for healthcare workers with emotional distress during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: a randomized clinical trial. 09.04.24313084 Preprint at (2024). https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.04.24313084 (2024).

de Castro, N. F. C., de Melo Costa Pinto, R., da Silva Mendonça, T. M. & da Silva, C. H. M. Psychometric validation of PROMIS® anxiety and depression item banks for the Brazilian population. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp Treat. Care Rehabil. 29, 201–211 (2020).

Pilkonis, P. A. et al. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the patient-reported outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment18, 263–283 (2011).

Schaufeli, W. B., Desart, S. & De Witte, H. Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT)—Development, validity, and reliability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17, 9495 (2020).

Sinval, J., Vazquez, A. C. S., Hutz, C. S., Schaufeli, W. B. & Silva, S. Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT): Validity evidence from Brazil and Portugal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 1344 (2022).

da Silva Machado, R. et al. Dropout in brief psychotherapy for major depressive disorder: randomized clinical trial. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 29, 1080–1088 (2022).

Hanevik, E., Røvik, F. M. G., Bøe, T., Knapstad, M. & Smith, O. R. F. Client predictors of therapy dropout in a primary care setting: a prospective cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 23, 358 (2023).

Linardon, J., Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., Brennan, L., Barillaro, M. & Wilfley, D. E. Dropout from interpersonal psychotherapy for mental health disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychother. Res. 29, 870–881 (2019).

Mulder, R., Murray, G. & Rucklidge, J. Common versus specific factors in psychotherapy: opening the black box. Lancet Psychiatry. 4, 953–962 (2017).

Cuijpers, P., Reijnders, M. & Huibers, M. J. H. The role of common factors in psychotherapy outcomes. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 15, 207–231 (2019).

Labrague, L. J. Psychological resilience, coping behaviours and social support among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J. Nurs. Manag. 29, 1893–1905 (2021).

Chigwedere, O. C., Sadath, A., Kabir, Z. & Arensman, E. The impact of epidemics and pandemics on the Mental Health of Healthcare Workers: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 6695 (2021).

Moura, E. C. et al. Covid-19: evolução temporal e imunização nas três ondas epidemiológicas, Brasil, 2020–2022. Rev. Saúde Pública. 56, 105 (2022).

Produto Interno Bruto - PIB | IBGE. https://www.ibge.gov.br/explica/pib.php

Khazaie, H., Rezaie, L., Shahdipour, N. & Weaver, P. Exploration of the reasons for dropping out of psychotherapy: a qualitative study. Eval Program. Plann. 56, 23–30 (2016).

Koç, V. & Kafa, G. Cross-cultural research on psychotherapy: the need for a change. J. Cross-Cult Psychol. 50, 100–115 (2019).

Sue, S. & Zane, N. The role of culture and cultural techniques in psychotherapy: a critique and reformulation. Am. Psychol. 42, 37–45 (1987).

Jacob, K. S. Employing psychotherapy across cultures and contexts. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 35, 323–325 (2013).

Soto, A., Smith, T. B., Griner, D., Domenech Rodríguez, M. & Bernal, G. Cultural adaptations and therapist multicultural competence: two meta-analytic reviews. J. Clin. Psychol. 74, 1907–1923 (2018).

Lucas, J. J. & Moore, K. A. Psychological flexibility: positive implications for mental health and life satisfaction. Health Promot Int. 35, 312–320 (2020).

Haider, S. I. et al. Life satisfaction, resilience and coping mechanisms among medical students during COVID-19. PloS One. 17, e0275319 (2022).

El-Monshed, A. H. et al. Satisfaction with life and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: an Egyptian online cross-sectional study. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam Med. 14, 6 (2022).

Stefanowicz-Bielska, A., Słomion, M. & Rąpała, M. Life satisfaction of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 16789 (2022).

Trumello, C. et al. Psychological Adjustment of Healthcare Workers in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic: differences in stress, anxiety, Depression, Burnout, secondary trauma, and Compassion satisfaction between Frontline and Non-frontline professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17, 8358 (2020).

Clement, S. et al. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol. Med. 45, 11–27 (2015).

de Osório, L. F. et al. Mental health trajectories of Brazilian health workers during two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021). Front. Psychiatry 14, (2023).

Kegel, A. F. & Flückiger, C. Predicting Psychotherapy dropouts: a Multilevel Approach. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 22, 377–386 (2015).

Robinson, L., Delgadillo, J. & Kellett, S. The dose-response effect in routinely delivered psychological therapies: a systematic review. Psychother. Res. 30, 79–96 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Vania Naomi Hirakata for her support in statistical analysis. To researchers Christian Kristensen and Lucas Spanemberg for their assistance in protocol development. To Malu Macedo and Lívia Hartmann for their supervision activities with the therapists. We would also like to thank all the psychotherapists responsible for the care of the patients.

Funding

This study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Health (TED no. 16/2020) and sponsored in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S.M.: conception and planning of the study; data collection; elaboration and writing of the manuscript; intellectual participation in therapeutic conduct of the cases studied; statistical analysis; critical review of the literature; critical review of the manuscript, approval of the final version of the manuscript.M.B.B.: approval of the final version of the manuscript; elaboration and writing of the manuscript.M.deA.C.: critical review of the manuscript, approval of the final version of the manuscript.M.PA.F.: intellectual participation and critical review of the manuscript and approval of the final version of the manuscript.G.A.S.: approval of the final version of the manuscript; effective participation in research orientation; intellectual participation and critical review of the manuscript.C.B.D.: approval of the final version of the manuscript; conception and planning of the study; intellectual participation, statistics analysis and critical review of the manuscript.G.G.M.: Statistical analysis; approval of the final version of the manuscript; conception and planning of the study; elaboration and writing of the manuscript; effective participation in research orientation; intellectual participation and critical review of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martins, D.S., Bermudez, M.B., de Abreu Costa, M. et al. Predictors of dropout in cognitive behavior and interpersonal online brief psychotherapies for essential professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep 14, 30316 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81327-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81327-9