Abstract

This study employs Conversation Analysis to create a recursive model that improves the quality of human-robot interaction. Our research goal is to create a dialogue robot that offers pleasant experiences for users, so they are willing to engage in repeated interactions in daily lives. While there has been dramatic progress in the performance of dialogue robots, there has been less attention to the importance of users’ interactional experience compared to the “specs” of the dialogue system. Employing Goffmanian insights and using research in Conversation Analysis (CA), the present study develops a dialogue closing system to exit the interaction. We then experimentally verified that the robot with the dialogue closing system performs better in the user’s perception of the robot (i.e. likeability, politeness, and dialogue satisfaction) than the control group. Further, by analyzing the dialogue between the human and the robot through CA, we propose to build a recursive, reflective model to improve the dialogue model design. A constructive approach urges us to reproduce complicated social phenomena in human-robot interaction so that we can investigate the underlying cognitive mechanisms of humans and create robots that can convey human-like cognition functions and coexist with humans. Taking such a constructive approach, we posit that our recursive model for dialogue systems that uses CA insights and then qualitatively analyzes conversational data can enhance the quality of dialogue systems because the model elucidates which properties of a conversation humans need to experience a conversational robot as human-like. Our study suggests that interactional morality - particularly conversational closings - is one property of human interactions that humans likely require social robots to adhere to.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As more robots are supporting and enhancing our everyday lives, improving the quality of robot-human conversations has been a central research agenda for the past 40 years. As a result, the quality of conversations robots can engage with a human has improved drastically. Robots can competently understand the meaning of human utterance1,2, gauge human emotions3as well as the intentions of their human conversational partner4, identify their conversation partner and recall past conversation3, and consider users’ preferences5,6. In sum, advances in dialogue systems improved the quality of the contentsof human-robot conversations quite drastically. Robots are therefore starting to appear in our everyday lives in more situations such as home7, museum8, hotels9, shopping malls3,10, airports11, and schools12.

Compared to such advances in the dialogue systems in terms of the contents of the conversation, there is less attention to conversational forms. This is probably due to assumptions in the Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) community that successful task accomplishment would lead the user satisfaction. We argue that a complementary focus on interactional experience is needed: especially given that with robots entering into everyday human settings, we interact with them in a repeated manner, and given that there are more and more companion robots that are non-task based. For these robots, sociality is ever more important because users do not simply expect particular tasks to be accomplished by the robot (e.g. telling the weather) but continuous and repeated pleasant interactions. The interaction is, in itself, a core part of the task.

In this paper, we focus on one particular conversational form, the closing. There are a few good reasons to focus on the closing. First, there has been scant attention to how a robot should exit the engagement with its human counterpart. Even in state-of-the-art non-task-oriented dialogue systems (e.g13.) with deep learning technologies, the focus is on how to continue the conversation with its user. The recent call for a design process for exit put forward by Björling and Riek14 makes clear that the lack of robust design for the robot’s smooth exit makes users vulnerable because they cannot control their engagement effectively. Second, as the proverb “All’s Well That Ends Well”suggests, the ending has a vast potential for improving the users’ perception of the robot and reassessing the entirety of the conversation, and behavioral economics similarly suggests that people’s memory of the experience is skewed toward the peak experience and the end15. Third, as sociologist Erving Goffman16 famously posited, exiting an interaction is a moral affair. Goffman notes that the closing of a conversation is particularly difficult because it risks the relationship the conversationalists have established. The persons - or a human and a robot, in our case - must close the conversation while “saving face” for their conversation partner, and helping them maintain their reputation, dignity, and identity. Robots then need to possess interactional sensitivities similar to humans to exit the conversation without breaching social norms to be ethical as well as useful.

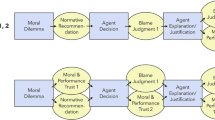

Drawing on such insights, we employ CA and implement a dialogue closing system that accounts for the interactional moral rules for dialogue closing. Ishiguro17has proposed a constructive approach for social robots. A constructive approach aims at reproducing “complicated social phenomena, whose underlying principles are unknown, with robots to investigate the underlying mechanisms”17. By aiming to realize a robot that behaves and interacts like a human, we not only learn the necessary and sufficient conditions for a robot to engage with a human-like a human, but we also gain insights on human meta-level cognitive functions which then can help us design better robots. In this paper, we show one implementation of such a constructive method - we use a dialog system that was inspired by human conversation closing sequences and analyze the interaction between an android and a human. Our results show that the dialogue closing system significantly improves users’ evaluation of the conversational experience and enhances their motivation to engage with the robot in future interactions. We also showcase a recursive model of dialogue system development where we further analyze the sequences of the human-robot interactions through CA to gain insights for continuously improving the dialogue system as well as deciphering which conversational properties humans are likely to expect of a social robot.

Motivation

As Kahneman et al15. famously observed, people evaluate their experience primarily by their peak experience and by its ending. Yet, if that is the case, experiences of human-robot interactions can be vastly improved by paying attention to interactional endings. While researchers on conversational systems have focused on how to help robots sustain conversations, they paid scant attention to how to end them. The assumption is that when the task is accomplished, the conversation can end. This research fills the lacuna and focuses on the closing of the conversation. We argue that a smooth and amicable closing is essential for realizing a conversational robot that could establish long-term relationships with humans: as is the case for human-to-human conversations, a positive conversational closing experience would induce users to enter future interactions with the robot.

These conversational closings, as interactionist research has suggested, are crucial in human interactions. As Erving Goffman16 put it, the closingof a conversation effectively summarizes the relationship the conversationalists established, and also is a potential threat to their “face” - the positive social value a person effectively claims for himself by the line others assume he has taken during a particular contact”16. Leaving a conversation is a delicate interactional accomplishment. Drawing on insights initiated by Goffman and subsequently developed Conversation Analysis (CA) methods of analyzing human interactions, we propose a dialogue closing strategy that creates smooth, polite, and well-prepared conclusions to robot-human conversations that mimic human-human conversation closings. Whereas such closing strategy may look simply “polite”, we posit that politeness is not simply a matter of mannerism, but it undergirds the basic morality of social interaction16; farewells are of particular import because such interaction rituals cement the successful end to the interaction, assuring that the social relationship is intact and can be continued. We hypothesize that people employ similar interactional rules for human-robot interaction to human-human interactions, and thus the closing is an important part of the interactional experience. As the quality of the conversation a robot can have with humans improves in complexity as well as its human-likeness, it is essential that a robot can end conversations without being abrupt or, worse, rude. In human social interactions, the closing cements the social relationships between the conversationalists, preparing the ground for their next encounter with each other. We, therefore, test whether a robot that can end the interaction on a good note would elicit better satisfaction about the interaction and willingness to engage with the robot continuously.

To accomplish our research goals of creating a dialogue robot that users experience the interaction as smooth and pleasant, we start with Goffman’s16original insight that exiting an interaction requires an interaction ritual because closing a conversation constitutes double threats, as (1) it may damage the relationship fostered during the interaction, and (2) it may pose negative face threat, where interacting parties may feel disrespected16,18. Goffman notes that to avoid an abrupt and uncalled for departure, people often strive to predict whether their interactional counterparts are indeed intending to end the interaction - and initiate the closing only when they are fairly certain that their counterpart is ready for it to end16. Literature in conversation analysis (CA) shares the same insights; closing an interaction is a coordinated interactional accomplishment that both conversationalists must orient to19. Conversation analysts found that humans give multiple signals before initiating closing through both bodily movements - such as stepping away slightly, or angling of the body to signal an upcoming disengagement20,21, and turn-taking. For turn-taking, conversationalists look for a potential topic closing - and they only initiate pre-closing upon establishing the last conversational topic was closed, and a single conversation can potentially come to an end19,22,23.

In most human-robot interactions, unfortunately, this kind of detailed attention for every turn is precisely what the robot lacks - they either end interaction quickly when their intended purpose is fulfilled in cases of purposeful social robots (e.g. information guide robots) or strive to engage the user as long as possible by asking follow up questions and making comments without a long pause. Both strategies create an awkward experience for users. In this paper, we focus on improving the dialogue model (and not on sensory information retrieval or robots’ movements). Because CA research shows that humans initiate multi-step closing interactions to avoid potential breach of interactional morality, our strategy for closing is designed to give the user multiple signals that the interaction is coming to an amicable end. Following the CA literature on conversation closings18,19,22, we identified four strategies that people use to close conversational sequences in a natural, smooth, and respectful way. (1) Goal/Summary - an utterance that summarizes the interaction as a way to start the closing interactions (2) Positive comment - an utterance that posits that the interaction was a positive experience for the conversationalists; (3) General wish - an utterance that preemptively repairs the solidarity threatened by leaving, and lastly; (4) Thanks - expressing appreciation for the conversation. While in human-to-human conversations the order in which these four strategies are used by a person who wants to conclude the conversation is variable, we simplified the closing method to be able to implement it as a dialogue model. Thus, in our study, we implement the four strategies in one sequence of Goal/Summary-Positive comment- General wish- Thanks. According to the literature, this order of the four strategies is most frequently used by those who want to initiate and complete the closing of the conversation among humans18.

This study hypothesizes that the dialogue robot with the closing strategy performs better in the user’s perception of the robot. Specifically, we suppose that they can feel (H1) its politeness and (H2) satisfaction and continued motivation to engage with it for the next time. Here, politeness indicates that the robot can follow interactional moral rules, thus keeping people’s social selves and dignity intact. As we explained in Motivation, we argue such a successful ending will lead to more user satisfaction and their willingness to continuously engage with the robot. The contributions of this study are as below:

-

We propose a dialogue closing strategy that can be easily implemented in conversational robots

-

We show clear evidence that such a strategy elicits greater user satisfaction and willingness to engage with the robot for repeat interactions

-

We explore a new research paradigm of a recursive and reflexive design cycle for a more user-friendly dialogue system utilizing Interaction and Conversation Analysis

In the following sections, we describe related works and then explain a dialogue robot system equipped with the proposed method. We also report and discuss the results of a validation experiment to verify the above hypotheses.

Related work

The goal of this study is to develop a dialogue strategy that can be implemented in a robot and enable a smoother, respectful, and amicable closing to the human-robot conversation. To satisfy this requirement, we implement insights from Conversation Analysis on the ways humans manage to close the conversation. In this section, we describe the novelty of our approach by comparing it with previous HRI studies that have either focused on conversational endings or employed interactional and conversational-analytic research strategies and insights.

To estimate users’ wish to terminate the conversation with a robot, Ogawa et al.24. developed a model to estimate the user’s willingness to continue the conversation through the analysis of the vocal information such as pitch, the length of the utterance, and its interval. Maruyama et al.25. employed verbal and non-verbal information to estimate the willingness of the user to continue the conversation. Other methods estimate user’s engagements by combining these information26,27. While these studies are useful in their attempt to know when the robot should terminate the interaction, they do not offer the dialogue strategy for exit itself. The current research thus offers a concrete dialogue strategy that can be easily implemented in conversational robots.

Some research has also attempted to leverage Goffmanian Interaction Analysis and Conversation Analysis to design the opening strategies for human-robot interactions, and to help sustain human-robot interactions. Most of such work focus on the opening where the robot is tasked with starting an engaged interaction. For example, whether passersby intend to talk to a robot can be gauged and facilitated when the robot understands the bodily posture of that person and focuses their gaze as a sign of interactional invitation28. Pitsch et al.29. used insights from Interaction Analysis to elicit the user’s commitment to the engagement with a robot by using pauses and restarts. Arend and Sunnen30similarly showcased the usefulness of Interaction analysis to analyze breakdowns of human-robot interactions. Funakoshi and Komuro31and Komuro and Funakoshi32analyzed human-robot interactions through Conversation Analysis to accumulate insights on how human operators may compensate for the robot’s interactional awkwardness, and how users attend to the lag in conversations during human-robot interaction. While these studies have extensively exemplified the utility of Interactional Analysis and Conversation Analysis in HRI research, they have not implemented the insights gained by the method directly, except for Gehle et al.33. showing how robots with a stepwise coordinated strategy for opening can elicit a more focused encounter. In our research, we create a dialogue strategy for closing based on works in Conversation Analysis, test its effectiveness in a controlled experimental setting, and analyze the results through Conversation Analysis as well as quantitative analysis. By doing so we aim to start a recursive and reflexive design cycle for a more user-friendly dialogue system utilizing Interaction and Conversation Analysis.

System

Dialogue system

In this study, we developed a dialogue system with a strategy for the closing. The flowchart of the dialogue is shown in Fig. 1. Summary/Goal, Positive Comment, General Wish, and Thanks phases are related to the closing. For the dialogue before closing, we applied the modeling dialogue system that estimates the user’s preference6. The reason for this is to avoid the possibility that the content of the dialogue differs from the user to the user when we verify the effect in an experiment. To perfectly control the closing utterances, the dialogue system in this study is built by a rule-based style. It is possible to change the modeling module to another dialogue system.

The details of the modeling phase can be found in prior work6, but here we provide an overview of it. The goal of the module is to efficiently learn a user’s preferences through natural dialogue interactions. The system represents user preferences using a preference table and similarities between items using a similarity table. The tables store numeric values indicating like/dislike and similar/dissimilar. It estimates missing values in the tables using complementation rules, like inferring user preferences for one item based on their preferences for a similar item. It generates two types of utterances: data acquisition to directly ask users their preferences/similarities, and data confirmation to verify its estimated values. To efficiently build a model of the user’s preferences, the system calculates an expected complementation amount (ECA) to select which missing value to ask the user about. This aims to maximize table completion through dialogue.

When the modeling is over, the system generates utterances of the Summary/Goal phase (e.g., “Today, I am glad to know where you want to go.”). Its next behavior depends on whether the user agrees or disagrees with it. If agrees, the phase shifts to Positive Comment (e.g., “It’s fun to talk about travel, isn’t it?”). If disagrees, since Positive Comment cannot be uttered as the next phase, the system makes an utterance of Backchannel (e.g., “I see...”) and General Wish Comment (e.g., “Well, good luck with the rest of your day.”). If the user agrees with the utterance of Positive Comment, it performs the utterance of General Wish. If the user disagrees to the comment, the backchannel is performed, and the phase shifts to the General Wish phase. After that, it generates an utterance of Thanks (e.g., “Thank you very much for coming today.”), and the dialogue is terminated. The full text of the candidate utterances for each phase in this study is listed in the section of Supplementary Material ??. The system randomly selects one of them for each phase.

Dialogue Robot

We adopted an android (Geminoid F: Fig. 2) as a dialogue robot, which has 12 Degrees of Freedom (DoF). The key point made by Ishiguro’s 2006 research is that a robot exhibiting human-like behaviors allows people to better comprehend its human-resembling capabilities from a design perspective. When robots act in human-like ways, we can construct an understanding of their lifelike attributes. This constructive understanding is facilitated by androids with human appearance and mannerisms. Their humanoid interface enables users to more readily grasp the robot’s human-likeness. In contrast, this type of conceptual understanding is more difficult with machine-like robots that do not display human qualities. Therefore, the ability to promote constructive understanding of an android’s human-likeness is a major reason we argue it is highly beneficial to incorporate humanoid robots in conversational systems. The human-resembling android provides critical scaffolding for people to meaningfully build mental models of the robot’s human attributes based on its anthropomorphic appearance and behaviors.

The recognition and generation basically followed the system of Glas et al34.. We used the Wizard of Oz (WoZ) method35for speech recognition. It is widely used in the field of human-robot interaction (HRI) to avoid misrecognition of user utterances which affect the evaluation of dialogue strategies. For speech synthesis, we used VOICE TEXT ERICA36. Regarding motion generation, we used the system of Higashinaka et al37.. The android displays human-like body language and gestures while speaking. Its lip, head, and body movements are synchronized with its voice. These natural motions are generated automatically based on the voice output, using systems developed in prior research. In addition to the synchronized gestures, it randomly blinks its eyes while talking, adding further naturalness to the conversation.

Experiment

In this section, we describe an experiment for verifying the effectiveness of the proposed dialogue robot system. Two experimental conditions were prepared: a proposed condition and a control condition. The former is a condition that generates dialogues according to the method described in section 4. In the control condition, the flowchart in Figure 1 was set to transition to “Thanks” after Modeling was completed. The number of turns of the dialogue was controlled in both conditions (3 turns is the difference of Closing). Each participant experienced the dialogue in both conditions and answered a questionnaire in a within-participants design. The current study adopted it since individual differences between participants could affect the evaluation and this effect could be counteracted by it. The participants were instructed not to ask the android any questions, but only to respond to what they were asked. In the second dialogue condition, they were further instructed to speak as if they were a different interlocutor than previous dialogue. The order of the conditions was counterbalanced. The dialogue scene in the experiment is shown in Figure 3. The participants are instructed to sit in front of the android for each condition. After each condition of interaction, they are directed to another room to complete questionnaires.

This study used two types of questionnaires: one pre-experimental questionnaire answered before the experiment and the evaluative survey after each condition. The same modeling module is used in both conditions, and that module requires that the items subject to preferences and similarities be registered in advance. In the pre-experimental questionnaire, following the method of Uchida et al.6, we asked the participants to choose the domestic (Japanese) sightseeing spots that they know, so that the robot would pick up the sightseeing spots that the participants knew from among 30 items as the topics of the modeling. After answering the pre-experimental questionnaire, the participant sat in front of the android over a table. The conversation about sightseeing was then initiated by the android. There are two main questionnaires which are answered after each condition. The first is an impression evaluation of the robot by using factors of Anthropomorphism, Animacy, Likeability, and Perceived Intelligence of Godspeed38. The second is a questionnaire about the dialogue, with the following items.

-

Listening: This robot was listening to me very well

-

Understanding: This robot understood what I said

-

Friendliness: I felt this robot’s friendliness

-

Satisfaction: I enjoyed talking with this robot

-

Motivation: I would like to talk with this robot again

-

Politeness: This robot was polite

We referred to previous studies6 regarding Understanding, Satisfaction, and Motivation. The participants were asked to answer these questions on a Likert scale of 7 (1. not at all agree—7. strongly agree) after completing each condition. The present study was approved by the Osaka University Ethics Committee. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. We took informed consent from the participant in Figs. 3 and 7 for publication of identifying information/images.

Results

27 Japanese people (18 male, 9 female, average age 23.07, standard deviation 7.22) participated in this experiment.

Quantitative analysis

The results of Godspeed38 are shown in Figure 4. A paired t-tests were conducted on the means of the participants for each item. It revealed a significant difference in Likeability (\(p = 0.04\)) and no significant differences for Anthropomorphism (\(p = 0.47\)), Animacy (\(p = 0.96\)), and Perceived Intelligence (\(p = 0.20\)).

The mean scores for each item in Godspeed38. The error bars mean standard errors (*\(p < 0.05\)).

Figure 5 shows the results of the impressions of the dialogues. A paired t-test was conducted for each item, and no significant differences were found for, Understanding (\(p = 0.79\)), Affinity (\(p = 0.60\)), and Motivation (\(p = 0.39\)). On the other hand, significant differences were found for Satisfaction (\(p = 0.02\)) and Politeness (\(p = 0.04\)).

These results indicate that dialogue androids with the dialogue strategy of closing significantly improve their likeability, politeness, and dialogue satisfaction. This means that H1 was supported while H2 was partially supported.

Qualitative analysis

To complement the quantitative analysis, we also employed Conversation Analysis (CA) to analyze dialogues recorded during the experiment. Our analysis shows that the dialogue strategy with closing sequences elicits smoother and more amicable endings to the conversation compared to the control. In Figure 6, we show the sequences of the conversation during the experiment. We chose this particular example as it is representative of all recorded closing interactions using the proposed dialogue model.

Line 1 marks the last sequence of the modeling part of our experiment. In Line 1, the robot asks the subject whether they liked another sightseeing location, estimated by our preference estimation model. After the confirmation of their approval (“I like it.”), the robot acknowledges the receipt of the answer (“I see.”) and then initiates the first part of the closing sequence - Summary. Note, most dialogue systems would transition to an end at Line 3 by saying something like “Thank you for coming today.” (We do not show the sequences from the Control condition due to the lack of space here.) Summary suggests that the preceding conversation was successful and therefore complete, and sets the ground for the end of the interaction. The subject takes this invitation up and verbally affirms the Summary in Line 4. Thus, in Line 5 the robot moves on to the next sequence, Positive Comment - which directly works to disaffirm the possibility that the conversation or the conversation partner was problematic in any way. The subject clearly understood this as an invitation to closing, evident by their remark “Thank you” and the bowing in Line 8 - a clear signal of the end of the encounter. The robot is still engaged with the closing sequence, which is designed to give ample opportunities for the closing even if the subject did not take the Summary - Positive comment sequences as a part of the closing sequences. Thus, Lines 9–10 are slightly redundant for the subject - the robot at last clearly marks the end of the conversation by Thank you, to which the subject does not respond verbally but acknowledges the closing with the nod and the last bow.

The qualitative analysis presented here shows how the closing of this dialogue system performs in real time. The interaction is smooth because the participant is well aware of the end of the conversation, and can leave on a positive note. We also propose that this could lay the groundwork for a recursive model of dialogue development—we implemented dialogue sequences based on CA, took a video recording of the interaction between a human and a robot during their conversation, and then analyzed the interaction between the human and the robot using the dialogue model again.

While we are only in the early stages of the development of such a model, we can already derive a few important insights on dialogue systems and show the utility of our recursive model for developing a dialogue system through CA insights. There are some properties of conversational rules - that the literature in CA has documented - that humans seem to expect a conversing robot to adhere to. For example, humans can tolerate the delays in response by a robot - and speak with more intervals as they orient themselves to speaking to an entity with a human-like, but not human, cognition. However, it seems that people are less adaptable to other properties of conversation that carry moral significance such as the closing. The abrupt closing of interaction is a breach in human-to-human interaction, and our quantitative and qualitative analysis of the recorded conversations shows that this is one thing that we must design better.

Discussion

In this study, we implemented a dialogue strategy of the closing, which was constructed based on CA, in a dialogue android. Its effectiveness was verified quantitatively and qualitatively through an experiment. The experimental results show that the proposed method improves the android’s likeability, politeness, and dialogue satisfaction. The post-analysis of the recorded interaction in CA also shows the smoothness of the closing of this dialogue system. Further, we proposed a recursive, reflective, model to improve dialogue strategy by having a dialogue model that is inspired by CA, implementing the model in real-time with users, and analyzing the conversations between the user and the robot through CA. Such a feedback loop for developing a dialogue system is advantageous because we can gain direct user feedback on the quality of interaction and implement the insight in a dialogue system in systematic ways (Fig. 7). We showcased the recursive model of dialogue system development where we further analyze the sequences of the human-robot interactions through CA to gain insights for continuously improving the dialogue system as well as deciphering which conversational properties humans are likely to expect of a social robot.

While the proposed method significantly improved the users’ satisfaction with the conversation, it did not significantly improve their motivation for repeated interactions. This result corresponds to that of Uchida et al6.. One possible reason for this is that the present dialogue was conducted in a laboratory setting, and it was not imaginable for the participants to conduct a continuous interaction aside from an experimental setting. Future studies that allow repeated voluntary interactions, such as robots that give recommendations for food in a food court, are needed to verify whether the robot with a better exit strategy motivates users to have repeated interactions.

In this experiment, to control the number of turns in the dialogue, the proposed condition has seven turns of utterances of the Modeling phase whereas the control condition has ten turns. Given these utterances are considered to give the impression that the robot is listening to the user, understanding them, and having intelligence, we could expect the proposed system to score below the control condition. Nevertheless, we did not observe significant differences in the Listening, Understanding, and Perceived Intelligence items, suggesting that the proposed method maintains these impressions while improving likeability, politeness, and dialogue satisfaction. While the proposed method was effective in terms of sociality such as politeness, it did not affect users’ perceptions of the robots’ anthropomorphism and animacy.

In this study, we conducted our experiment using an android that closely resembles humans in appearance. Using a media that resembles humans in appearance and communicates in a human-like manner is essential for testing how the conversational rules upheld by human conversationalists can be employed by robots for smooth interaction. We took a Constructive approach17 and tried to reproduce conversations between humans with a human and an android to gain insights on improving the dialogue system as well as human cognition. Namely, we found that the proposed method with dialogue closing strategy performs better than the control because humans prefer an android that ends conversations with interactional morality to the alternative. One of our future tasks is to verify the effectiveness of the proposed method with robots other than androids, as it is possible that people are more lenient with sudden interactional endings when interacting with other types of robots.

We verified the effectiveness of a closing strategy in which the android initiates the closing of the conversation unilaterally after the predetermined number of turns. To create a more comprehensive strategy for exit, however, the robot needs to perform an exit strategy when the task is complete or whenever the user desires to leave. Furthermore, the user might require a faster closing in some contexts, especially in a real setting. Also, the optimal number might differ depending on whether the dialogue is task-oriented or non-task-oriented. Thus, further studies are needed to develop a model that takes users’ signals for the exit, as well as formulate a strategy that combines the estimation of the user’s willingness for continued engagement that had been done in previous research.

Lastly, we note that Japanese people participated in this experiment. Goffmanian interaction analysis and CA are by no means culture-specific - the interactional morality on exiting the interaction, and the properties of the conversational rules are considered to be universal. Nevertheless, we recognize the possibility that some aspects of what was tested in this study could be culturally dependent, as Japanese culture is known to place importance on politeness. Future works need to be conducted to verify whether the proposed method is generally effective in diverse cultures.

Conclusion

Employing Goffmanian insights and using research in Conversation Analysis (CA), the present study develops a dialogue closing system to exit the interaction. We then experimentally verified that the robot with the dialogue closing system performs better in the user’s perception of the robot (i.e. likeability, politeness, and dialogue satisfaction) than the control group. Further, by analyzing the dialogue between humans and robots through Conversation Analysis we propose to build a recursive, reflective model to improve the dialogue model design. We showcase the recursive model of dialogue system development where we further analyze the sequences of the human-robot interactions through CA to gain insights for continuously improving the dialogue system as well as deciphering which conversational properties humans are likely to expect of a social robot. Our study suggests that interactional morality—particularly conversational closings—is one property of human interactions that humans likely require social robots to adhere to.

Additional information

The authors took informed consent from all the participants. The participants signed informed consent regarding publishing their data.

Data availability

The data in this study is provided within the manuscript.

References

Jokinen, K. & Wilcock, G. Multimodal open-domain conversations with the nao robot. In Natural Interaction with Robots, Knowbots and Smartphones, 213–224 (Springer (eds Mariani, J. et al.) (New York, NY, New York, 2014).

Nakano, M. et al. A two-layer model for behavior and dialogue planning in conversational service robots. In 2005 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 3329–3335 (IEEE, 2005).

Kanda, T., Shiomi, M., Miyashita, Z., Ishiguro, H. & Hagita, N. An affective guide robot in a shopping mall. In Proceedings of the 4th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human Robot Interaction, HRI ’09, 173–180, https://doi.org/10.1145/1514095.1514127 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2009).

Uchida, T., Minato, T. & Ishiguro, H. Embodiment in dialogue: Daily dialogue android based on multimodal information. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 1261, 012016 (IOP Publishing, 2022).

Kobayashi, S. & Hagiwara, M. Non-task-oriented dialogue system considering user’s preference and human relations. Transactions of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence : AI 31, DSF–A_1 (2016). (in Japanese).

Uchida, T., Minato, T., Nakamura, Y., Yoshikawa, Y. & Ishiguro, H. Female-type android’s drive to quickly understand a user’s concept of preferences stimulates dialogue satisfaction: Dialogue strategies for modeling user’s concept of preferences. International Journal of Social Robotics 13, 1499–1516 (2021).

Gates, B. A robot in every home. Scientific American 296, 58–65 (2007).

Shiomi, M., Kanda, T., Ishiguro, H. & Hagita, N. Interactive humanoid robots for a science museum. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM SIGCHI/SIGART Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, HRI ’06, 305–312, https://doi.org/10.1145/1121241.1121293 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2006).

Nakanishi, J. et al. Can a humanoid robot engage in heartwarming interaction service at a hotel? In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Human-Agent Interaction, 45–53 (2018).

Sakamoto, Y., Uchida, T. & Ishiguro, H. An autonomous conversational android that acquires human–item co-occurrence in the real world. In 2022 31st IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 743–748 (IEEE, 2022).

Tonkin, M. et al. Design methodology for the ux of hri: A field study of a commercial social robot at an airport. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 407–415 (2018).

Kanda, T., Sato, R., Saiwaki, N. & Ishiguro, H. A two-month field trial in an elementary school for long-term human-robot interaction. IEEE Transactions on robotics 23, 962–971 (2007).

Xu, J., Szlam, A. & Weston, J. Beyond goldfish memory: Long-term open-domain conversation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.07567 (2021).

Björling, E. & Riek, L. Designing for exit: How to let robots go. Proceedings of We Robot (2022).

Kahneman, D., Fredrickson, B. L., Schreiber, C. A. & Redelmeier, D. A. When more pain is preferred to less: Adding a better end. Psychological Science 4, 401–405 (1993).

Goffman, E. Interaction ritual: essays on face-to-face behavior (Pantheon, New York, 1967).

Ishiguro, H. Constructive approach for interactive robots and the fundamental issues. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 1–2 (2021).

Coppock, L. Politeness strategies in conversation closings. Unpublished manuscript: Stanford University (2005).

Raymond, G. & Zimmerman, D. H. Closing matters: Alignment and misalignment in sequence and call closings in institutional interaction. Discourse Studies 18, 716–736 (2016).

Broth, M. & Mondada, L. Walking away: The embodied achievement of activity closings in mobile interaction. Journal of Pragmatics 47, 41–58 (2013).

Tuncer, S. Walking away: An embodied resource to close informal encounters in offices. Journal of Pragmatics 76, 101–116 (2015).

Schegloff, E. & Sacks, H. Opening up closings, semiotica, viii (4), 289-327 (1973).

Robinson, J. D. Closing medical encounters: two physician practices and their implications for the expression of patients’ unstated concerns. Social science & medicine 53, 639–656 (2001).

Ogawa, Y., Murakami, M. & Shirai, K. Construction of decision model for the spoken dialogue system to close communication. SIG Technical Reports (HCI) 2011, 1–8 (2011) ((in Japanese)).

Maruyama, K., Yamato, J. & Sugiyama, H. Analysis of how motivation to conversation varies depending on the number of dialogue robots and presence/absence of gestures. The IEICE transactions on information and systems 104, 30–41 (2021) ((in Japanese)).

Inoue, K., Lala, D., Takanashi, K. & Kawahara, T. Latent character model for engagement recognition based on multimodal behaviors. In International Workshop Spoken Dialogue Systems (2018).

Yu, Z., Ramanarayanan, V., Lange, P. & Suendermann-Oeft, D. An open-source dialog system with real-time engagement tracking for job interview training applications. In Advanced social interaction with agents, 199–207 (Springer, 2019).

Mutlu, B., Shiwa, T., Kanda, T., Ishiguro, H. & Hagita, N. Footing in human-robot conversations: How robots might shape participant roles using gaze cues. In Proceedings of the 4th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human Robot Interaction, HRI ’09, 61–68, https://doi.org/10.1145/1514095.1514109 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2009).

Pitsch, K. et al. “the first five seconds”: Contingent stepwise entry into an interaction as a means to secure sustained engagement in hri. In RO-MAN 2009-The 18th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, 985–991 (IEEE, 2009).

Arend, B. & Sunnen, P. Coping with turn-taking: investigating breakdowns in human-robot interaction from a conversation analysis (ca) perspective. In Proceedings: The 8th International Conference on Society and Information Technologies, 149–154 (2017).

Funakoshi, K. & Komuro, M. Toward mindful machines: A wizard-of-oz dialogue study. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Humanized Computing and Communication (HCC), 94–99 (IEEE, 2019).

Komuro, M. & Funakoshi, K. Attitude towards dialogue robot as interactional practice. Transactions of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence 37, A–L61 (2022).

Gehle, R., Pitsch, K., Dankert, T. & Wrede, S. How to open an interaction between robot and museum visitor? strategies to establish a focused encounter in hri. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 187–195 (2017).

Glas, D. F., Minato, T., Ishi, C. T., Kawahara, T. & Ishiguro, H. Erica: The erato intelligent conversational android. In 2016 25th IEEE International symposium on robot and human interactive communication (RO-MAN), 22–29 (IEEE, 2016).

Fraser, N. M. & Gilbert, G. N. Simulating speech systems. Computer Speech & Language 5, 81–99 (1991).

ReadSpeaker, https://readspeaker.jp/ (5/6/2024).

Higashinaka, R. et al. Spoken dialogue system development at the dialogue robot competition. THE JOURNAL OF THE ACOUSTICAL SOCIETY OF JAPAN 77, 512–520 (2021) (in Japanese).

Bartneck, C., Kulić, D., Croft, E. & Zoghbi, S. Measurement instruments for the anthropomorphism, animacy, likeability, perceived intelligence, and perceived safety of robots. International journal of social robotics 1, 71–81 (2009).

Jefferson, G. Glossary of transcript symbols. Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation 24–31 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by JST Moonshot R&D Grant Number JPMJMS2011 (conceptualization, system development, and experiment), JST PRESTO Grant Number JPMJPR23I2 (summarizing and discussing experimental result), and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 19H05693 (system development and experiment) and 22K17949 (summarizing and discussing experimental result).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (T.U., N.K. and H.I.) contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, and data collection were performed by T.U. and N.K. T.U. analyzed the results. All authors (T.U., N.K. and H.I.) approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Uchida, T., Kameo, N. & Ishiguro, H. Improving the closing sequences of interaction between human and robot through conversation analysis. Sci Rep 14, 29554 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81353-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81353-7