Abstract

Doxorubicin is an anthracycline antibiotic widely used in cancer therapy. However, its cytotoxic properties affect both cancerous and healthy cells. Combining doxorubicin with antioxidants such as ferulic acid reduces its side effects, while simultaneously enhancing therapeutic effectiveness. The low bioavailability of these drugs demonstrate that drug delivery carriers are required to enable the target site to be accessed. The doxorubicin and ferulic acid-loaded liposome composed of HSPC, Cholesterol, and DSPE-mPEG2000 (55:40:5 molar ratio) was prepared by thin film hydration method. The findings indicate that the encapsulation of ferulic acid had an impact on liposome characteristics, i.e., increasing the particle size of Lipo-DOX from 134.5 ± 4.8 nm to 154.1 ± 5.2 nm for Lipo DOX-FA, increasing the zeta potential of Lipo-DOX from − 16.04 ± 2.59 to 0.2 ± 0.0 mV for Lipo DOX-FA, and reducing the entrapment efficiency percentage of Lipo-DOX from 88.30 ± 1.89% to 85.99 ± 3.02% for Lipo DOX-FA. The infrared spectra of Lipo DOX-FA exhibited shifted absorption bands, indicating the interaction between the carboxyl group of ferulic acid and the choline polar head of phospholipid. Moreover, changes to the DSC thermogram were observed following the incorporation of ferulic acid into the liposome, while the Lipo DOX-FA exhibited a relatively rapid drug release compared to Lipo DOX suggesting a slightly shorter period necessary to attain both therapeutic efficacy and the maintenance of a stable drug encapsulation in the systemic circulation. An in vitro study of LLC and HeLa cells showed that the IC50 values of Lipo DOX-FA were 0.70 µg/mL and 1.56 µg/mL, while the CC50 value in normal HEK cells was 6.50 µg/mL. This study suggested that while co-loading FA into Lipo DOX reduced the IC50 value, indicating enhanced cytotoxicity in cancer cells, it had no effect on DOX liposome cytotoxicity in normal HEK cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Doxorubicin (DOX), an anthracycline drug often forming part of anticancer therapy, acts through DNA intercalation and inhibition of the topoisomerase II enzyme which impedes the cell synthesis process and causes apoptosis1. DOX can transform into semiquinones through an oxidation mechanism, producing free radicals that lead to cell death2,3. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that DOX possesses cytotoxic properties which particularly impact myocardial cells. The administration of DOX triggers oxidative stress due to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the depletion of cellular antioxidants4. This oxidative stress-induced myocardial injury manifests itself through the generation of free radicals which stimulate myocyte peroxidation, ultimately resulting in intracellular calcium influx5.

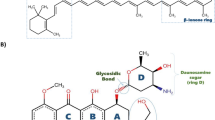

Combining cancer medications with antioxidants may constitute a means of reducing the harmful impact on healthy cells. Certain natural compounds, such as ferulic acid (FA) derived from plants, contain polyphenol groups and possess both anticancer and antioxidant properties, suggesting their potential role in supporting cancer treatments6. Ferulic acid’s capacity to reduce reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby demonstrating antioxidant and anti-inflammatory attributes, inhibits lipid peroxidation and cellular apoptosis in normal cells7. Through its anticancer function, FA induces the expression of Fas Cell Surface Death Receptor Ligand (FASLG) on T47D breast cancer cells, thereby playing a pivotal role in apoptosis signaling8. Furthermore, FA effectively suppresses COX-2 and VEGF-2, pro-angiogenic factors, resulting in reduced inflammation and angiogenesis9. The combination of DOX and FA produces a synergistic effect in reducing free radicals, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the lipid peroxidation marker, malonyl dialdehyde (MDA), ultimately leading to the inhibition of oxidative stress in H9c2 cardiomyocyte cells10. This combination exerted both similar and more profound effects than either free DOX in MCF-7 and MDA-MB 231 cancer cells10. The cytotoxicity assay results relating to DOX with a combination of polyphenol compounds such as Naringenin at a ratio of 1:1 indicated that polyphenol compounds can synergistically increase the cytotoxic effect of DOX in T47D breast cancer cells11. The combination of DOX with FA as an anticancer agent has a synergistic anti-proliferative effect in breast cancer cells, as evidenced by a combination index (CI) value of less than 0.9 and a dose reduction index (DRI) for each drug when used in combination12.

Unfortunately, due to poor pharmacokinetic and physicochemical properties, both drugs have a high clearance in the bloodstream. DOX has a clearance of 30 L/h/m2 and Vd 23 L/kg13. Meanwhile, ferulic acid has low bioavailability, namely ~ 20% and t1/2 1.10 and 1.39 min14,15. Within the context of cancer therapy-related drug delivery systems, it is crucial to devise strategies that prolong a drug’s presence in the bloodstream, while preventing opsonization by the reticuloendothelial system. Liposomes offer several noteworthy advantages as carriers in this regard.

Liposomes constitute a vesicle-shaped delivery system with a water compartment surrounded by a phospholipid bilayer layer, a structure enabling it to deliver both lipophilic and hydrophilic drugs16,17. Liposomes are widely used as delivery systems due to their biocompatibility, greater stability, uncomplicated synthesizing process, and higher drug loading efficiency18. Stealth liposomes have more numerous advantages compared to conventional liposomes. The presence of polyethylene glycol in liposomes prevents their opsonization resulting in a longer circulation time in the bloodstream19,20. Doxil, one of the commercially available stealth liposome products, demonstrates clearance which is five times lower, a smaller distribution volume (Doxil is 4 L while free DOX is 254 L), and higher exposure to tumor cells compared to free DOX13,21. Apart from DOX, FA also penetrates cells more rapidly compared to its free form when delivered in a liposome22. Loading both drugs into liposomes produces beneficial effects such as enhancing anticancer activity and reducing side effects.

In this study, FA was trapped in DOX liposomes with PEGylation. It has been reported that the half-life of free FA at a dose of 10 mg/kg is 1.39 min, and that it is rapidly excreted after 15 min of intravenous administration15. In a previous study, FA was proven to have antioxidants that were more effective than other polyphenols in the lecithin liposomal system and dilute emulsions23. Encapsulation of FA in nanolipid carriers can provide controlled release and lower drug clearance than free FA24. FA demonstrates higher solubility in intraliposomal solution than in the extraliposomal phase resulting from salt gradient. Consequently, the drug can be trapped in the liposome without precipitation22.

This study was conducted to determine FA co-loading’s effects on the physicochemical characterization and cytotoxicity profiles of FA co-loaded PEGylated DOX liposomes.

Results

Particle size and zeta potential of DOX-FA liposomes

The loading of FA and DOX combination into liposomes exhibited an inclination towards an increase in particle size larger than that of DOX liposome. As presented in Fig. 1a, the largest liposome size, characterized by an average diameter of 154.1 ± 5.2 nm, was attained with Lipo DOX-FA. Meanwhile, each liposomal formulation’s polydispersity index (PDI) indicated values < 0.5, signifying a homogenous size distribution. The smallest PDI value was obtained with the Lipo-FA formula, as depicted in Fig. 1b. Regarding zeta potential values, Lipo-DOX exhibited an average zeta potential of −16.04 ± 2.59 mV, while Lipo-FA displayed an average zeta potential value of 0.7 ± 0.3 mV. In the case of Lipo DOX-FA, the zeta potential value was − 0.2 ± 0.0 mV, as observed in Fig. 1c. The encapsulation efficiency (EE) of DOX in liposomes is shown in Fig. 1d. The results indicated no significant difference between the %EE of DOX for both Lipo DOX and Lipo DOX-FA which were 88.30 ± 1.89%, and 85.99 ± 3.02% respectively. However, the %EE value of Liposome DOX-FA showed a slightly lower value. On the other hand, the %EE of FA in Lipo FA differed significantly from Lipo DOX-FA, which decreased from 4.10 ± 0.05% to 1.50 ± 0.11% respectively, as presented in Fig. 1e.

TEM morphology of the liposomes

The liposome’s vesicle morphology was evaluated by TEM analysis, and the results are presented in Fig. 2. As can be seen in the picture, the Lipo-FA had spherical shapes with no aggregate or any solid formation inside the vesicles (Fig. 2A). At the same time, the Lipo-DOX shows an oval vesicle with an aggregate-like formation inside the liposome, as indicated in Fig. 2B. Co-loading FA with DOX into liposomes forming Lipo-DOX-FA produced vesicles without any aggregate formation in the intraliposomal phase region, as shown in Fig. 2C.

FTIR spectra profiles of DOX-FA liposomes

The FTIR spectra of the liposome components can be observed in Fig. 3, while the liposome formulations are depicted in Fig. 4. Based on these results, the Lipo-Blank exhibited bands that were identical to those of the liposome constituents. However, a reduction in the intensity of absorption bands compared to the liposome constituents’ spectra was observed. This was indicated by a broad absorption range of 900–1,004 cm−1 for the N+(CH3)3 functional group (975 cm−1), identical to the absorption band of HSPC. Moreover, there were C = C aromatic stretch groups (1,600–1,700 cm−1) of cholesterol identical to those in the blank liposome, with an absorption peak at 1,667 cm−1. Furthermore, functional groups such as -OH bending (1,330–1,440 cm−1), C-H stretching (2,700–3,000 cm−1), and C-H bending (1,330–1,440 cm−1) were present in the blank liposome spectra. They matched the absorption bands of cholesterol, HSPC, and DSPE-mPEG2000, as can be observed in Fig. 3.

Meanwhile, in the FTIR spectra of the liposome formulations, there were absorption bands corresponding to C-H stretch, C = C stretch, N+(CH3)3, and C = C groups that were present in all liposome formulas, as seen in Fig. 4. Furthermore, the absorption bands of specific functional groups, namely -OH, were observed in Lipo-FA and Lipo-DOX, along with a shift towards lower wavenumbers, while phenolic -OH bending was only found in Lipo-FA and Lipo-DOX-FA. The absorption of -CO-O was detected in both Lipo-FA and Lipo-DOX-FA, but in neither Lipo-Blank nor Lipo-DOX. The symmetric phosphate group at a wavenumber of 1,253 cm−1 was not observable in Lipo-FA or Lipo-DOX. In Lipo-DOX-FA, a sharp absorption band at a wavenumber of 1,068 cm−1 was also observed, indicating an increase in intensity.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) of DOX-FA-loaded liposomes

Thermal analysis was conducted using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) for liposomes and lipid components of the liposome, as depicted in the thermogram contained in Fig. 5. In the lipid components, HSPC, DSPE-mPEG2000, and cholesterol exhibited their respective endothermic peaks at temperatures of 78.6 °C for HSPC, 57.8 °C for DSPE-mPEG2000, and 150.6 °C for cholesterol. Furthermore, when the lipid components were assembled into liposomes, a shift in the endothermic temperatures to higher values occurred, specifically 183.4 °C for Lipo-Blank. After loading with drugs, i.e., DOX and FA, the endothermic temperature decreased to 183.1 °C for Lipo-FA, and 172.2 °C for Lipo-DOX. These endothermic temperatures differed from those of free DOX and FA, i.e., 200.6 °C and 174.8 °C respectively. However, they were similar for Lipo-Blank. When both were combined, five broad thermogram peaks could be observed, as shown in Fig. 5. This may indicate changes in the ordered structures of the liposomal membranes due to the drug loaded inside and possibly interaction between liposomal components that produced different thermal properties in Lipo DOX-FA.

In vitro DOX released from DOX-FA-loaded liposomes

The cumulative percentage of DOX released from both Lipo-DOX and Lipo DOX-FA can be observed in Fig. 6. The cumulative percentage results indicate values that are not significantly different. However, it is noticeable that the release of DOX from Lipo DOX-FA was relatively more rapid than that of Lipo-DOX, suggesting a more permeable or fluid structure of the liposomal membrane. Furthermore, the release flux showed results of 4.62 ± 0.93% cumulative released per hour for Lipo-DOX and 4.96 ± 1.12% cumulative released per hour for Lipo-DOX-FA, as indicated in Table 1.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay of DOX-FA-loaded liposomes

The cytotoxicity of the free drugs, i.e., DOX, FA, and their combination (DOX-FA), the liposomes namely, Lipo DOX, Lipo-FA, and Lipo DOX-FA on LCC, HeLa, and HEK cells was evaluated after the sample exposure of approximately 48 h, as can be seen in Fig. 7. According to the results, DOX showed high cytotoxicity in LLC and HeLa cells, and HEK cells whose IC50 values were 1.41, 1.57, and 0.23 µg/mL as shown in Fig. 7a-c. On the other hand, FA had no anti-cancer or toxic effects on these cells, as can be seen from Fig. 7d-f. Combining free DOX with FA improved its cytotoxicity, resulting in lower IC50 in LLC and HeLa cells. However, it was also toxic for HEK cells. The in vitro assay on LLC, HeLa, and HEK cells indicated that Lipo DOX-FA had higher cytotoxicity with the IC50 values of 0.70, 1.56, and 6.50 µg/mL respectively, than the Lipo-DOX, which had the IC50 values of 1.41, 1.96, and 39.89 µg/mL. In addition, DOX-FA dual loading into liposomes (Lipo-DOX-FA) also resulted in higher cytoxicities than those of Lipo-FA in the cells in question. FA and Lipo-FA generally had no cytotoxic effects on LLC and HeLa cells, or the very high CC50 levels in HEK cells, thereby indicating their lack of threat to normal cells.

Viability of cells after treatment with various concentrations of DOX (0.001; 0.005; 0.05; 0.15; 0.5; and 3 µg/mL) for DOX, Lipo-DOX, DOX-FA 10 µg/mL, DOX-FA, and Lipo DOX-FA, towards (a) LLC cell, (b) HeLa cell and (c) HEK cell; and various concentrations of FA (0.5; 1; 5; 10; 50; and 180 µg/mL) for FA, Lipo-FA, FA + DOX-FA 0.15 µg/mL, DOX-FA, and Lipo-DOX-FA toward (d) LLC cell, (e) HeLa cell and (f) HEK cell. Cells were then incubated for 48 h before the MTT reagent was added. The IC50 and CC50 values in a-c refer to the DOX concentration, while the d-f values relate to FA concentration.

Discussion

In this study, DOX liposomes were combined with FA to reduce the cytotoxicity of the drugs administered to normal cells. while still producing high cytotoxicity in the case of cancer cells. DOX is a chemotherapeutic agent demonstrating both high solubility in water and high permeability25,26. When injected, it targets not only cancer cells but also normal ones, especially cardiomyocytes9,27, causing cardiotoxicity due to the effects of the free radical it contains. As an antioxidant, FA is expected to counteract the mechanisms of DOX that produce ROS, thereby protecting cardiomyocytes and mitigating cardiotoxicity28. Liposomal delivery carrier is intended to stably encapsulate these combined drugs, enabling their high accumulation in cancer tissues and minimal presence in normal tissues. The composition of liposomes can significantly affect the effective delivery of DOX and FA. Therefore, this study evaluated the effects of adding FA to the characteristics and morphology of DOX liposomes.

The combination of FA and DOX increased the particle size of the liposomes. This could be due to molecular conjugation forming new larger molecules which increased the liposome particle size29,30. Moreover, the DOX active loading process resulted in the accumulation of DOX inside the liposomes, which may lead to aggregate formation and further particle size expansion. Irrespective of the greater particle size, both Lipo-DOX and Lipo-DOX-FA remained within the 20–200 nm range, allowing them to accumulate at cancer sites through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect mechanism31.

The addition of FA, which was subsequently combined to form Lipo-DOX-FA, also altered the potential charge of the liposomes. The presence of FA changed the average charge of Lipo-DOX from − 16.04 ± 2.59 mV to −0.2 ± 0.0 mV. The phospholipid component of the liposomes can influence Zeta potential. In the case of Lipo-DOX, this charge can be considered close to neutral as it falls to approximately − 10 mV. Liposomes with a neutral charge typically have zeta potential values ranging from − 10 mV to + 10 mV32. The neutral charge may be attributed to a hidden effect caused by the DSPE-mPEG2000 layer on the liposome’s surface33. With the addition of FA, the zeta potential of the liposomes approached zero. This could result from FA, DOX, and lipid bilayer interactions. One possible hypothesis is the competition between ferulic acid and cholesterol within the lipid bilayer structure, leading to non-uniform molecular distribution34. In previous research, liposomes containing FA alone, without added DOX, exhibited zeta potential values ranging from − 0.4 mV to −1.2 mV35. Generally, a higher zeta potential value suggests stronger electrostatic repulsion between particles, enhancing stability. However, the latter quality can also be influenced by factors such as particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and stabilizing agents such as PEGylated lipids. While the zeta potential of Lipo-FA and Lipo DOX-FA is relatively low-neutral, the study conducted by Nakamura et al. (2012) indicates that liposomes with near-neutral zeta potential can still achieve colloidal stability through steric stabilization provided by PEGylated lipids on the surface of liposome36. The interactions between FA, DOX, and the lipid bilayer probably contribute to this near-neutral charge, resulting in a balance between electrostatic and steric stabilization. The PEG chains create a physical barrier that prevents particle aggregation, thereby enhancing the colloidal stability of the liposome. This effect is significant for formulations with near-neutral zeta potential, as it compensates for the lack of electrostatic repulsion. However, further stability tests are necessary to confirm the stability of Lipo DOX-FA.

The encapsulation efficiency percentage of DOX-FA Liposomes had a slightly lower value than Lipo DOX, which were 85.99 ± 3.02 and 88.30 ± 1.89% respectively. This was probably due to the presence of FA inside the liposome, which reduces the intraliposomal capacity to load DOX by active loading in Lipo-DOX-FA. It has been reported that the hydrophobic part of FA can occupy the space between the lipid bilayer membrane and the hydrophilic core of liposome35, with the result that less DOX enters the liposome as when the DOX alone is loaded in Lipo-DOX. In addition, there was a reduction of FA loaded in Lipo DOX-FA which probably occurred due to leakage during the incubation of liposomes with DOX.

Interactions within the liposomes were also observed in the FTIR spectra and the DSC thermogram profiles, reflecting the rigidity of the liposomal membrane and affecting the physicochemical properties of liposomes37,38. These interactions within the liposomes can be detected through the absorption of specific functional groups such as (R–PO2–R’), ester groups (–CO–O), and N+(CH3)3 from HSPC39,40,41. In liposomes loaded with FA or DOX and their combination, spectral peaks related to the P = O antisymmetric group that were absent from Lipo-FA, Lipo-DOX, and Lipo DOX-FA. Simultaneously, there was a shift towards lower wavenumbers in the symmetric phosphate groups. This indicates the presence of hydrogen bonding between the polar head of the liposome and DOX or FA. The decrease in wavenumbers may suggest strengthening existing hydrogen bonds or the forming of new hydrogen bonds42.

Meanwhile, the loss of the anti-symmetric phosphate group indicates that both FA and DOX are located in the interfacial region of the membrane41. The negatively charged carboxyl group of FA can interact with the positively charged choline head of HSPC35. It has been established that DOX contains NH3+ that can interact with the -OH groups of glycerol in phospholipids, bringing NH3+ closer to the phosphate groups and enhancing their interaction, resulting in a shift to lower wavenumbers43.

The DSC thermogram profiles showed no significant changes in the endothermic temperature among the Lipo-Blank and the liposome components. The slightly higher endothermic temperature observed in the Lipo-Blank thermogram indicates structural changes of crystalline structures of the liposomal membrane composed of various lipids and a more compact or ordered structure44. In Lipo-FA and Lipo-DOX, there was a noticeable decrease in the peak endothermic temperature, suggesting interactions between DOX and the liposome membrane45,46. Meanwhile, Lipo DOX-FA featured more numerous endothermic and exothermic peaks, especially in the thermogram temperatures related to the liposome components. This indicates interactions between DOX and FA, which can bring back peaks from the constituent lipids of the liposome and exhibit exothermic peaks, indicating recrystallization47.

In the DOX release study of Lipo-DOX and Lipo-DOX-FA, no significant difference was observed. However, it was noted that the release of DOX from Lipo-DOX-FA tended to be higher than that from Lipo-DOX, indicating that Lipo-DOX is relatively more rigid37,48. A more rigid membrane typically results in a slower drug release49. The higher release of DOX from Lipo-DOX-FA suggests a more fluid liposome membrane structure. This could be due to interactions with the choline portion of phospholipids which can influence the fluidity of the liposome35.

The results of in vitro cytotoxicity assays of Lipo DOX-FA in LLC and HeLa cells show an increase in cytotoxicity compared to Lipo-FA or Lipo-DOX, indicating that FA improves the cytotoxicity of DOX. However, exposure to normal HEK cells also resulted in higher cytotoxicity. Based on these results, it can be seen that Lipo-FA is not cytotoxic in relation to cancer cells, i.e., LLC and HeLa cells, and this result was also observed for HEK cells. These results predict that FA could improve the toxic effects of DOX since it is known that FA triggers synergistic anti-proliferative activity in cancer cells. FA, as an anti-cancer agent, expresses apoptotic proteins FAS/FASLG, p53, and p21 that inhibit the cancer cell growth50. Furthermore, it can also be extrapolated those certain effects ensued from the addition of FA with regard to liposomal membrane fluidity, thus resulting in higher drug release from those liposomes to be further exposed to the cells37,38,48 However, these results require further clarification to confirm which effects dominate the synergistic effects of the DOX-FA combination in studies of cancer.

Conclusion

Dual loading of FA combined with DOX in the liposomes has been successfully achieved, although it increased the particle size and reduced the potential charge of the liposomes. Furthermore, interactions between FA and DOX and the liposome membrane occurred leading to changes to wave numbers and the absence of peaks associated with particular functional groups, as evidenced by the infrared spectra, as well as modifications to the thermogram profiles of the liposomes. These interactions resulted in changes to the liposome membrane, leading to increased fluidity and a heightened rate of DOX release from the liposome. Research has demonstrated that the inclusion of FA amplifies the cytotoxicity of DOX in cancer cells. Nevertheless, the safety of FA in comparison to DOX liposomes for normal cells has not been substantiated, necessitating additional research to investigate the potential application of FA to chemotherapy.

Materials and methods

Materials

Hydrogenated soya phosphatidylcholine (HSPC) and distearylphospatidyl-ethanolamine-methoxy-(polyethylene-glycol) (DSPE-mPEG2000, the mean molecular weight of PEG is 2000 g/mol) were purchased from NOF Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Cholesterol was obtained from Wako Pure Chemical Industries Inc. (Osaka, Japan). Triethanolamine was obtained from Sigma Aldrich, Co. Ltd. (Darmstadt, Germany). Doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX) was secured from LC Laboratories (Woburn, Massachusetts), and Ferulic Acid (FA) was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan). Phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) comprised 8 g sodium chloride, 0.2 g potassium chloride, 1.15 g disodium hydrogen phosphate, and 0.2 g potassium dihydrogen phosphate per liter (Oxoid Ltd., Hampshire, UK). All other chemicals used in this study were of the highest grade available.

Preparation of liposomes

Blank liposome (Lipo-Blank), FA liposome (Lipo-FA), DOX liposome (Lipo-DOX), and DOX-FA liposome (Lipo DOX-FA) were prepared with HSPC, Chol, and DSPE-mPEG2000 at a molar ratio of 55:45:5, using the thin-film hydration method49. The drugs were then loaded into the combination of DOX and FA at a molar ratio of 1:1. Firstly, all lipid components were dissolved in the appropriate amount of chloroform in a round-bottomed flask. Then, the chloroform was removed completely using a rotary vacuum evaporator in a water bath at 60 °C. After formation of a thin lipid film, it was hydrated with a hydrating solution: 0.65 M TEA solution for preparing Lipo-Blank and Lipo-DOX and 2 mg/mL FA in 0.65 M TEA solution for preparing Lipo-FA and Lipo DOX-FA. The pH of the hydration solution was adjusted to pH 6.3. The suspension was then vortexed for 1–2 min, followed by sonicating in a water bath at 60 °C for five minutes. The liposomes were continuously passed through polycarbonate membranes with pore sizes of 400, 200, and 100 nm with an extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids, USA). The external phase of liposomes was then replaced by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4 using a Sephadex G-50 gel filtration column. DOX was subsequently loaded into Lipo-DOX and Lipo DOX-FA at a drug-to-lipid weight ratio of 1:5, and incubated in a water bath at 60 °C for five minutes. Free DOX was then separated from these liposomes using the Sephadex® G-50 column elution.

For the purposes of encapsulation efficiency evaluation, after loading DOX to the liposome, the free DOX was separated from those liposomes using the Sephadex G-50 column elution. The liposome suspension that had been collected was then added to Triton X-100 (final concentration 5% v/v) as a lysis agent and sonicated for ten minutes. This process was intended to damage the liposome membrane and release the drug from the liposome. The concentration of DOX subsequently entrapped in the Lipo-DOX and Lipo DOX-FA was measured using a Shimadzu RF-6000 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) at λ = 480 nm.

For the measurement of FA, the liposome suspension was mixed with methanol (at a volume ratio of 1:2) as a lysis agent and sonicated for ten minutes. This process was intended to destruct the liposome membrane and release the drug inside. The FA level was determined by adding Folin Ciocalteu reagent (Merck Inc., Darmstadt, Germany). Then, the mixtures were stirred until homogeneous and allowed to stand for three minutes in a darkened room or wrapped in aluminum foil. Furthermore, about 1,380 µl of distilled water and 200 µl of 7.5% Na2CO3 solution were added and incubated for 30 min at 45 °C. The concentration of FA entrapped in the Lipo-FA and Lipo DOX-FA was measured at room temperature with a Shimadzu RF-6000 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) at λ = 780 nm. The percentage of entrapment efficiency of each drug was calculated using the following formula38:

Measurement of particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and ζ potential of liposomes

Particle size and PDI of the liposomes were measured with a dynamic light scattering method using Delsa Nano C Particle Analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, USA). The zeta potential of the liposomes was measured with an electrophoretic light scattering photometer, Zetasizer Nano Zs (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern, UK) at Sepuluh November Institute of Technology (ITS), Surabaya, Indonesia, and Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB), Bandung, Indonesia. To obtain sample measurements, approximately 100 µL liposomes were diluted with 3 mL of demineralized water, put into a cuvette, with particle size, PDI, and zeta potential all being subsequently measured.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis of liposomes

TEM analysis was conducted to evaluate the morphology of liposomes. Liposomes were diluted with aquadest at an appropriate volume ratio, dripped on a TEM’s grid, left for 1 min, and drained by soft wiping with filter paper. Then, UranyLess EM Stain was dripped on the sample as negative staining, left for 1 min, and the remaining staining was wicked away with filter paper. The morphology of vesicles was further observed with Hitachi TEM HT7700 (Hitachi, Japan), which was set at a maximum acceleration voltage of 120 kV with a maximum magnification of 600,000 times and a sample thickness of 100 nm.

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analysis of liposomes

FTIR evaluation was carried out to determine component interaction within the liposome. The FTIR spectra of freeze-dried liposomes were recorded using an Alpha II Infrared Spectrophotometer (Bruker Massachusetts, America). Scanning was carried out at room temperature in the wavenumber range of 600–4,000 cm−1, and the spectra result was recorded in OPUS 8.1.29 application.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) profile analysis of liposomes

DSC was used to evaluate the liposome interaction evident from the endothermic and exothermic peaks. DSC evaluation was performed using the DSC 250 Instrument (TA Instrument, New Castle, Delaware). The liposome containing 7% sucrose was freeze-dried, and the de-hydrated samples were placed on aluminum crucibles and heated from 30 to 300 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/minute.

For DSC analysis, the sample must be in its solid state. Consequently, freeze-drying was carried out. However, this process can precipitate physical changes in the formulation associated with increased liposome size due to phospholipid membrane fusion which can occur during freezing, drying, or rehydration. Cryoprotectants have been added to the liposomal formulation to enhance the products’ functional characteristics and stability following freezing and drying. Carbohydrates are the preferred cryoprotectant for liposome dehydration/rehydration because they can operate as integrity membrane protectants51.

In vitro DOX release from DOX-FA-loaded liposomes

The release assay was conducted by placing a Lipo DOX-FA or Lipo-DOX sample into dialysis tubing Spectra/Por 7 with a Molecular Weight Cut-Off (MWCO) of 3,500 Da (Spectrum Laboratories Inc, America). Liposomes were then immersed in 50 mL of PBS pH 7.4 and continuously stirred in a water bath at 37 ± 1 °C and a stirring speed of 450 rpm. Sampling was conducted at 2, 4, 8, and 24 h, then replaced with fresh PBS pH 7.4. The DOX concentration was analyzed fluorometrically at λex = 475 nm and λem = 580–640 nm with GloMax Explorer NanoLuc Fluorimeter instrument (Promega Corporation, Madison, USA) at the Stem Cell Research and Development Center Laboratory, Airlangga University.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay of liposomes

Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) and Hela cells were obtained from the Stem Cell Research and Development Center, Universitas Airlangga (Surabaya, Indonesia) for this study. In contrast, the HEK cells were obtained from the Photobiology and Aging Lab at IBPS, Sorbonne University, France. LLC and HeLa cells were cultured in Rosewell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1,640 medium, while HEK cells were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM). Each medium was added to 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% amphotericin B. During the study, the cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. For the in vitro assay, each cell was seeded separately at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well in 96-well plates and maintained in the medium for 24 h before treatment. For the cytotoxicity assay, cells were treated with a medium containing various DOX concentrations in Lipo DOX and Lipo DOX-FA and a range of FA concentrations in Lipo FA. Each plate was then incubated for 48 h with cell viability being measured with an MTT assay. About 25 µL of 5 mg/mL 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium-bromide (MTT) reagent in PBS pH 7.4 was added to each well. The plates were then incubated for four hours to allow the formation of purplish water-insoluble molecule formazan. Dimethyl sulfoxide was added to each well to dissolve the formazan. Cell viability was expressed as a relative value of sample or treated cells’ absorbance at 600 nm compared to untreated cells. The inhibiting concentration (IC50) leading to 50% cell viability was calculated.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Mobaraki, M. et al. Molecular mechanisms of cardiotoxicity: A review on the major side-effects of doxorubicin. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 79, 335–344. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.4172/pharmaceutical-sciences.1000235 (2017)

Wang, J. & Yuan, Z. Gambogic acid sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to doxorubicin through ROS-mediated apoptosis. Cell. Biochem. Biophys. 67, 199–206 (2013).

Davies, K. J. A. & Doroshow, J. H. Redox cycling of anthracyclines by cardiac mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 3060–3067 (1986).

Wang, X. et al. Lysophosphatidic acid protects cervical cancer HeLa cells from apoptosis induced by doxorubicin hydrochloride. Oncol. Lett. 24, 267 (2022).

Rahman Syed Wamique Yusuf Michael & Ewer, S. A. M. Anthracycline-Induced Cardiotoxicity and the Cardiac-Sparing Effect of Liposomal Formulation. Int. J. Nanomed. 2, 567–583 (2007).

El-Bassossy, H., Badawy, D., Neamatallah, T. & Fahmy, A. Ferulic acid, a natural polyphenol, alleviates insulin resistance and hypertension in fructose fed rats: Effect on endothelial-dependent relaxation. Chem. Biol. Interact. 254, 191–197 (2016).

ElKhazendar, M. et al. Antiproliferative and proapoptotic activities of ferulic acid in breast and liver cancer cell lines. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 18, 2571–2576 (2019).

Singh Tuli, H. et al. Ferulic Acid: A natural phenol that inhibits neoplastic events through modulation of oncogenic signaling. Molecules 27. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27217653 (2022).

Ekowati, J., Hamid, I. S., Diyah, N. W. & Siswandono, S. Ferulic acid prevents angiogenesis through cyclooxygenase-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor in the chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane model. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 17, 424–431 (2020).

Chegaev, K. et al. Doxorubicin-antioxidant co-drugs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 23, 5307–5310 (2013).

Junedi, S., Susidarti, R. & Meiyanto, E. Naringenin meningkatkan efek sitotoksik doxorubicin pada sel kanker payudara T47D melalui induksi apoptosis. Ind. J. Pharm. Sci. 8, 85–90 (2010).

Guerriero, E. et al. Combining doxorubicin with a phenolic extract from flaxseed oil: evaluation of the effect on two breast cancer cell lines. Int. J. Oncol. 50, 468–476 (2017).

Mross, K. et al. Pharmacokinetics of liposomal doxorubicin (TLC-D99; myocet) in patients with solid tumors: an open-label, single-dose study. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 54, 514–524 (2004).

Kohno, M. et al. Oral administration of ferulic acid or ethyl ferulate attenuates retinal damage in sodium iodate-induced retinal degeneration mice. Sci. Rep. 10, 8688 (2020).

Shin, D. H. et al. HPLC analysis of ferulic acid and its pharmacokinetics after intravenous bolus administration in rats. J. Biomed. Transl. Res. 17, 1–7 (2016).

Laouini, A. et al. Preparation, characterization and applications of liposomes: state of the art. J. Colloid Sci. Biotechnol. 1, 147–168 (2012).

Skupin-Mrugalska, P. Liposome-based drug delivery for Lung Cancer. In Nanotechnology-Based Targeted Drug Delivery Systems for Lung Cancer, 123–160 (Elsevier, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-815720-6.00006-x.

Nsairat, H. et al. Liposomes: structure, composition, types, and clinical applications. Heliyon 8. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09394 (2022).

Gasselhuber, A., Dreher, M. R., Rattay, F., Wood, B. J. & Haemmerich, D. Comparison of conventional chemotherapy, stealth liposomes and temperature-sensitive liposomes in a mathematical model. PLoS One 7, e47453 (2012).

Sercombe, L. et al. Advances and challenges of liposome assisted drug delivery. Front. Pharmacol. 6. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2015.00286 (2015).

Barenholz, Y. Doxil® - The first FDA-approved nano-drug: Lessons learned. J. Controlled Release 160, 117–134. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.03.020 (2012).

Qin, J. et al. Preparation, characterization, and evaluation of liposomal ferulic acid in vitro and in vivo. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 34, 602–608 (2008).

Batista, R. Uses and potential applications of ferulic acid In Ferulic acid: antioxidant properties, uses and potential health benefits (ed. Warren, B.) 39–70 (Nova Science Publishers, 2014)

Hassanzadeh, P., Arbabi, E., Rostami, F., Atyabi, F. & Dinarvand, R. Aerosol delivery of ferulic acid-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers: a promising treatment approach against the respiratory disorders. Physiol. Pharmacol. (Iran). 21, 331–342 (2017).

Yamada, Y. Dimerization of Doxorubicin causes its precipitation. ACS Omega. 5, 33235–33241 (2020).

Aminipour, Z. et al. Passive permeability assay of doxorubicin through model cell membranes under cancerous and normal membrane potential conditions. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 146, 133–142 (2020).

Varela-López, A. et al. An update on the mechanisms related to cell death and toxicity of doxorubicin and the protective role of nutrients. Food Chem. Toxicol. 134. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2019.110834 (2019).

Sahu, R., Dua, T. K., Das, S., De Feo, V. & Dewanjee, S. Wheat phenolics suppress doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via inhibition of oxidative stress, MAP kinase activation, NF-κB pathway, PI3K/Akt/mTOR impairment, and cardiac apoptosis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 125, 503–519 (2019).

Rudra, A., Deepa, R. M., Ghosh, M. K., Ghosh, S. & Mukherjee, B. Doxorubicin-loaded phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated nanoliposomes: in vitro characterization and their accumulation in liver, kidneys, and lungs in rats. Int. J. Nanomed. 5, 811–823 (2010).

Ibrahim, M. et al. Release, and cytotoxicity of doxorubicin loaded in liposomes, micelles, and metal-organic frameworks: A review. Pharmaceutics 14. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14020254 (2022).

Dadpour, S. et al. The role of size in PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin biodistribution and anti-tumour activity. IET Nanobiotechnol. 16, 259–272 (2022).

Smith, L. et al. Long-term velaglucerase alfa treatment in children with gaucher disease type 1 naïve to enzyme replacement therapy or previously treated with imiglucerase. Mol. Genet. Metab. 117, 164–171 (2016).

Garbuzenko, O., Zalipsky, S., Qazen, M. & Barenholz, Y. Electrostatics of PEGylated micelles and liposomes containing charged and neutral lipopolymers. Langmuir 21, 2560–2568 (2005).

Aramaki, K. et al. Charge boosting effect of cholesterol on cationic liposomes. Colloids Surf. Physicochem Eng. Asp. 506, 732–738 (2016).

Andrade, S., Ramalho, M. J., Loureiro, J. A. & Pereira, M. C. The biophysical interaction of ferulic acid with liposomes as biological membrane model: the effect of the lipid bilayer composition. J. Mol. Liq 324, 14689 (2021).

Nakamura, K. et al. Comparative studies of polyethylene glycol-modified liposomes prepared using different PEG-modification methods. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Biomembr. 1818, 2801–2807 (2012).

Miatmoko, A. et al. Interactions of primaquine and chloroquine with PEGylated phosphatidylcholine liposomes. Sci. Rep. 11, 12420 (2021).

Miatmoko, A. et al. Dual loading of Primaquine and Chloroquine Into Liposome. Pharm. J. 66, 18–25 (2019).

Zhao, X. et al. Preparation of a nanoscale dihydromyricetin-phospholipid complex to improve the bioavailability: in vitro and in vivo evaluations. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 138, 104994 (2019).

Tai, K., Rappolt, M., Mao, L., Gao, Y. & Yuan, F. Stability and release performance of curcumin-loaded liposomes with varying content of hydrogenated phospholipids. Food Chem. 326, 126973 (2020).

Mady, M. M., Shafaa, M. W., Abbase, E. R. & Fahium, A. H. Interaction of Doxorubicin and Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine Liposomes. Cell. Biochem. Biophys. 62, 481–486 (2012).

Shafaa Preparation, characterization and evaluation of cytotoxic activity of tamoxifen bound liposomes against breast cancer cell line. Egypt. J. Biomedical Eng. Biophys. 0, 0–0 (2020).

Cong, W., Liu, Q., Liang, Q., Wang, Y. & Luo, G. Investigation on the interactions between pirarubicin and phospholipids. Biophys. Chem. 143, 154–160 (2009).

Demetzos, C. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC): a tool to study the thermal behavior of lipid bilayers and liposomal stability. J. Liposome Res. 18, 159–173 (2008).

Jobin, M. L. & Alves, I. D. The contribution of Differential scanning calorimetry for the study of Peptide/Lipid interactions the contribution of differential scanning calorimetry for the study of peptide/lipid in-teractions. https://doi.org/10.1007/978 (2021).

Das, A., Konyak, P. M., Das, A., Dey, S. K. & Saha, C. Physicochemical characterization of dual action liposomal formulations: anticancer and antimicrobial. Heliyon 5 (2019).

Nugraheni, R. W., Setyawan, D. & Yusuf, H. Physical characteristics of liposomal formulation dispersed in HPMC matrix and freeze-dried using maltodextrin and mannitol as lyoprotectant. Pharm. Sci. 24, 285–292 (2017).

Miatmoko, A., Asmoro, F. H., Azhari, A. A., Rosita, N. & Huang, C. S. The effect of 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium propane (DOTAP) addition on the physical characteristics of β-ionone liposomes. Sci. Rep. 13, 4324 (2023).

Miatmoko, A., Kawano, K., Yoda, H., Yonemochi, E. & Hattori, Y. Tumor delivery of liposomal doxorubicin prepared with poly-L-glutamic acid as a drug-trapping agent. J. Liposome Res. 27, 99–107 (2017).

Gao, J. et al. The anticancer effects of ferulic acid is associated with induction of cell cycle arrest and autophagy in cervical cancer cells. Cancer Cell. Int. 18, 102 (2018).

Guimarães, D., Noro, J., Silva, C., Cavaco-Paulo, A. & Nogueira, E. Protective effect of Saccharides on freeze-dried liposomes encapsulating drugs. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 7, 1–8 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Aristika Dinaryanti, M.Si. and Deya Karsari, M.Si. for kind assistantship in the in vitro cell study.

Funding

This study was financially supported by International Research Collaboration Top 300 Funding between Airlangga University, Indonesia and Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, United Kingdom, with a Grant Number 2564/UN3.LPPM/PT.0 L.03/2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M., P.K.C., A.I., J.E.: conception and design of the work; A.M., P.K.C., B.S.H., D.M.C., A.I., J.E.: Data acquisition; A.M., P.K.C., A.I., B.S.H., D.M.C., M.A., N.W.D., M.F.A., R.K.D., I.S.H., J.E.: Data analysis and interpretation; P.K.C., A.I., B.S.H., D.M.C.: Drafting the article; A.M., J.E.: critically revising the article for important intellectual content; A.M., P.K.C., A.I., B.S.H., D.M.C., M.A., N.W.D., M.F.A., R.K.D., I.S.H., J.E.: Final approval of the version to be published. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miatmoko, A., Christy, P.K., Isnaini, A. et al. Characterization and in vitro anticancer study of PEGylated liposome dually loaded with ferulic acid and doxorubicin. Sci Rep 15, 1236 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82228-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82228-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Optimization of Ferulic Acid-Loaded Transferosomal Gel Using Box-Behnken Design: A Novel Approach for Enhanced Photoprotection

Journal of Pharmaceutical Innovation (2026)

-

Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome with natural products for ischemia–reperfusion injury across organs: mechanisms, structure–activity relationships, and delivery innovations

Inflammopharmacology (2025)

-

Fabrication and Optimization of Chebulinic Acid-Loaded Liposomes Based on Carbopol-gel Employing Box-Behnken Design for Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

Journal of Pharmaceutical Innovation (2025)

-

Novel Squalene Based Nanostructured Lipid Carriers of Ketoconazole for Enhanced Skin Penetration and Better Anti-Fungal Control: An In-Vitro, Ex-Vivo and In-Vivo Evaluation

BioNanoScience (2025)