Abstract

This numerical investigation examines the performance and exergy analysis of parabolic trough solar collectors, focusing on the substitution of the conventional circular absorber with a rhombus-shaped absorber. By evaluating the thermal and fluid dynamics properties, this study aims to identify improvements in overall system performance and efficiency. This numerical study conducts a comprehensive thermal analysis of parabolic trough solar collectors by comparing a rhombus-shaped absorber with a conventional circular absorber. The analysis considers two rim angles of the parabolic trough, specifically 80° and 90°. Fluid flow rates ranging from 200 to 600 L per minute and inlet fluid temperatures spanning from 400 to 650 K are evaluated for each configuration. The objective is to determine the impact of absorber shape, rim angle, flow rate, and inlet temperature on the thermal performance and exergy efficiency of the system. Additionally, a slope error range of 0 to 2.5 mrad is incorporated into the study. The optical efficiency, thermal efficiency, exergy efficiency, and overall efficiency of the parabolic trough solar collector are estimated and compared for both absorber shapes. Results indicate that the thermal performance of the collector improves significantly with the rhombus-shaped absorber, showing maximum increases of 2.88% in thermal efficiency, 1.45% in exergy efficiency, and 1.4% in overall efficiency compared to the conventional circular absorber. These findings provide valuable insights for optimizing the design of parabolic trough solar collectors to enhance their overall efficiency and energy conversion effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parabolic trough collectors (PTCs) are among the most advanced and extensively utilized technologies for capturing solar thermal energy. Their ability to concentrate solar radiation onto a receiver tube, where a heat transfer fluid (HTF) circulates, makes them highly effective for generating high-temperature thermal energy. This energy can be utilized in various applications, including electricity generation, industrial process heat, and desalination. As the global demand for sustainable and renewable energy sources escalates, there is a pressing need for innovations that can enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of solar thermal systems. Solar energy is an abundant and clean source of energy. Solar radiation offers a viable alternative to conventional fossil fuels, which are a major contributor to global warming and environmental degradation. As the global demand for sustainable and renewable energy sources escalates, harnessing solar energy efficiently is crucial for fulfilling energy needs and combating climate change1,2,3,4. Traditionally, PTCs employ a circular absorber tube to capture and transfer concentrated solar energy. While this design has proven effective, there is ongoing interest in exploring alternative shapes that could potentially provide better heat transfer and thermal performance. Concentrated solar thermal technology is commercially utilized to harness thermal energy from sunlight. This technology employs mirrors to concentrate a large number of sun rays onto a small absorber, capturing heat at higher temperatures. The PTC technology stands as a well-demonstrated form of concentrated solar thermal technology, increasingly gaining competitiveness within the global power generation industry5,6,7,8,9,10. Numerous PTC power plants are operational worldwide6. In addition to electricity generation, the PTC is also utilized in various industrial process heat applications6. In PTC based power plants, solar energy is harnessed from sunlight and transferred to a HTF. The thermal energy from the HTF is then utilized in a Rankine cycle to produce electricity11,12.

In PTC based power plants, the heat energy from the sun rays is extracted and transferred to the HTF. Thermal energy from HTF is extracted in the Rankine cycle to generate electricity11,12. To effectively compete with more cost-effective conventional electricity generation technologies, it is crucial to enhance the efficiency of PTCs to achieve higher Rankine cycle efficiency. The Rankine efficiency can be enhanced by operating at higher temperatures, achieved through a higher concentration ratio (CR) of the PTC13. Enhancing the CR of PTC remains one of the key challenges in advancing PTC technology14. In the present study, the CR is defined based on the geometry as the ratio of the aperture area of the concentrator to the surface area of the absorber, as presented in Eq. (1). From Eq. (1), it is evident that for given trough dimensions, the CR of the PTC can be enhanced by reducing the size of the absorber, provided the optical performance remains unaffected.

But the size of absorber cannot be decreased beyond a certain limit on account of optical losses. Due to finite apparent size of the sun, even in a perfect collector, the reflected rays from a particular point of the mirror diverge and spread over some portion at the focal line15,16. The absorber should be of such size so as to intercept all the deviated rays. In collectors with errors ( optical and geometrical), the reflected rays may diverge more and may not be intercepted by the absorber17,18,19,20,21. Therefore, to minimize optical losses, the size of the absorber must be bigger enough so that all the reflected rays are intercepted. Hence the CR of a PTC cannot be increased beyond a certain limit without affecting the optical performance of the PTC. The maximum possible theoretical value of the CR is around 70 for the PTC with the tubular absorber22. But due to the presence of errors, the maximum value of CR for the commercially available parabolic trough is around 2722. From the above discussion, it is clear that the size of the absorber must be bigger enough to have better optical performance of the PTC system. But thermal performance of the PTC improves with absorber of smaller size as radiation and convection heat transfer to the atmosphere are reduced22.

In the past, many designs have been suggested to increase the CR by decreasing the absorber size22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. These studies have suggested secondary mirrors for the second stage concentration for improving the CR of the PTC. McIntire27 has proposed a concept of using second stage concentration for the linear parabolic collectors. Collares-Pereira et al.32 have presented a two-stage concentration for PTCs by using asymmetric non-imaging concentrators of the compound parabolic collector type at the second stage. It has been reported that the improvement in the CR is about 2.5 times compared to a conventional PTC. Omer and Infield33 have presented the design procedure for the two-stage concentration of the PTC. The primary-stage involves the parabolic trough concentrator, and secondary-stage involves the compound parabolic concentrator. A thermoelectric device is placed at the focus of the secondary reflector to produce electricity from heat. A significant improvement in the overall collector performance with a second-stage concentrator has been reported. Bakos et al.23 have used two flat secondary mirrors and insulation to improve the concentration of the PTC and reported a significant improvement in the collector efficiency with reduction in size of the absorber. Gee et al.25 analyzed the performance of the PTC by employing the secondary reflectors on the upper inner surface of the glass cover to reflect the escaping rays on to the absorber. LS2 collector with an absorber diameter of 55 to 70 mm and slope error of up to five mrad has been considered in their study. It has been reported that the improvement in the optical efficiency is 1%, the reduction in heat loss is 4%, and the maximum increase in the overall performance of the PTC is 1.4%. Wirz et al.24 have used different designs of secondary mirror, including insulation in the vacuum space, to improve the performance of the PTC. The authors reported an improvement of 1.6% in the thermal efficiency. Rodriguez-Sanchez and Rosengarten22 have used a single flat mirror for second stage concentration. The edge ray principle has been used to determine the size of the secondary mirror for different commercially available troughs. The authors have reported up to 80% improvement in the CR of the PTC. In all these studies mentioned above, secondary mirrors have been used to improve the CR of the PTC. However, the secondary mirrors create shadow on the collector, thus reducing the solar radiation collection capacity of the PTC. For example, in the study of Rodriguez-Sanchez and Rosengarten22, it has been found that the CR increases by up to 53.1% for Solar Kinetics T-700 collector with secondary mirror but with a loss of 23.5% energy on account of shadow effect due to secondary mirror.

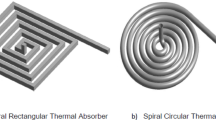

Donga and Kumar34 have proposed a new design to improve the CR of the PTC without using secondary mirrors. The conventional tubular absorber has been replaced with the new linear rhombus-shaped absorber. It has been observed that there is improvement in the CR up to 31.5% with 13.85% decrease in the absorber surface area. Donga and Kumar34 have studied only the optical performance of the PTC with the proposed absorber. For a given flow rate of HTF, pressure drop increases with reduction in size of absorber, thus increasing pumping power requirements. Therefore, it is vital to analyze the overall collector performance by estimating the thermal performance and pumping power requirement.

This study investigates the thermal performance of a PTC equipped with a rhombus-shaped absorber (RTA). A thermal analysis of the same PTC equipped with a circular tube absorber (CTA) has also been conducted. The thermal performance results of the PTC for both absorber types have been compared. The Euro trough collector with a focal length of 1.71 m has been considered for the study. Two rim angles of 80° and 90° have been taken. Slope error has been considered with a range 0 to 2.5 mrad. The analysis has been performed for different flow rates and inlet temperatures with range 200 to 600 l/min and 400 K to 650 K respectively. The study presents results on the variation in optical efficiency, temperature gradients in the absorber, pressure drop, thermal efficiency, exergy efficiency, and overall efficiency of the PTC, as influenced by inlet temperature and flow rate. The thermal analysis of the heat collection element (HCE) was performed using the finite volume method, while the optical analysis of the PTC was conducted using SolTrace software.

PTC Desing with rhombus tube absorber

The schematic of cross-section of the PTC has been presented in Fig. 1. As shown, the rays reflected from any given point on the mirror diverge due to finite sun angle and various errors present in the PTC system. The absorber size should take care of diverged rays by intercepting those over whole surface of the absorber. The distance between the mirror and its focal point is not constant in PTCs; it is minimum at the mirror’s vertex and maximum at the rim. Therefore, the absorber aperture should be lower when viewed from the vertex and higher when viewed from the rim in order to intercept diverged rays over the whole surface. Rhombus shape can meet these requirements, as shown in Fig. 2.

The cross-sectional view of the heat collection element (HCE) with CTA and RTA is shown in Fig. 3. The methodology presented in the study of Donga and Kumar34 has been used to calculate the dimensions of the RTA. The dimensions of the RTA have been calculated for two different troughs having rim angles, ψ = 80° and 90°, by keeping the acceptance angle (θ = 0.69°) constant34. The values obtained for various design parameters are presented in Table 1. Trough length is taken as 4 m. The CR of the PTC with CTA and RTA are calculated by using Eqs. (2) and (3), respectively.

Methodology

In this work, a numerical study has been performed to explore possibility of improving overall performance of the PTC system by employing rhombus tube absorber. Methodology and analysis carried out are presented in subsequent sections.

Optical analysis

SolTrace software has been used to carry out the optical analysis of the PTC. Monte Carlo ray tracing technique has been used35. The ray-tracing simulations have been performed for the PTC with CTA and RTA for the parameters specified in Table 1. The optical properties considered in the simulations are presented in Table 2. The sun angle of 2.6 mrad has been considered with Gaussian distribution, and the direct normal irradiation has been taken as 1000 W/m236,37. A total of 107 rays have been traced by doing a simple sensitivity analysis. The results obtained from ray-tracing have been validated with analytical results of the Jeter38, and results were found in good agreement as shown in Fig. 4.

Thermal analysis

The heat flux distributions derived from ray-tracing simulations were utilized for the thermal analysis of the heat collection element (HCE). Additionally, the useful heat gained by the heat transfer fluid (HTF) and the fluid flow pressure drop, as determined from numerical simulations of the HCE, were used to calculate thermal efficiency, exergy efficiency, and overall collector efficiency. The simulations also provided the temperature gradients in the absorber tube. The numerical simulations of the heat collection element (HCE) were conducted using the finite volume method, a technique known for its accuracy and widely utilized in previous research5,18,36.

Governing equations

The study employed the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations to analyze turbulent flow using the finite volume method. These equations capture the time-averaged conservation of mass, momentum, and energy, as detailed in Eqs. (4) to (6). For the simulations, the Realizable k-ε turbulent model with enhanced wall treatment was utilized to accurately represent turbulence effects18. The Realizable k-ϵ turbulent model was selected for simulation due to its demonstrated capability to accurately predict complex turbulent flows, including those characterized by strong boundary layer effects and heat transfer phenomena. Enhanced wall treatment improves accuracy in near-wall regions, rendering it appropriate for this application as the wall heat transfer is critical in this investigation. The model strikes a good balance between accuracy and computational efficiency.

Continuity equation:

Momentum equation:

Energy equation:

In the above equation, the Reynolds stresses, represented by \(- \rho \overline{{u_{i}{\prime} u_{j}{\prime} }}\) (Reynolds stresses) are computed using the eddy viscosity model, which applies the Boussinesq hypothesis to relate Reynolds stress to mean velocity gradients. Alongside the conservation equations for mass, momentum, and energy, radiative heat transfer is modeled using the discrete ordinates (DO) method.

Simulation framework and assumptions

The finite volume method (FVM) analysis is based on the following assumptions: (i) the flow is steady, (ii) material properties are isotropic and homogeneous, (iii) turbulence is present, (iv) all surfaces are treated as gray and diffusive, (v) buoyancy-induced turbulent kinetic energy is negligible, (vi) the fluid is incompressible, and (vii) heat exchange occurs solely through radiation between the absorber tube and the inner surface of the glass tube40. Syltherm800 has been selected as the heat transfer fluid40. Its physical properties—density (ρ), specific heat capacity (cp), thermal conductivity (λ), and viscosity (k)—are represented as polynomial functions of temperature, as detailed in Eqs. (7) through (10)36,40. Additionally, the thermal conductivity of the absorber material is specified as 54 W m⁻1 K⁻141.

\(\text{for} 283.15\le T\le 673.15\) K

\(\text{for} 283.15\le T\le 673.15\) K.

Boundary conditions

At the inlet mass flow rate and temperature of HTF have been specified, with values in the range from 2.13 to 7.02 kg/s and 400 to 650 K respectively. The pressure outlet is applied at the outlet of the HTF. No-slip boundary condition has been considered at the inner surface of the absorber. The heat flux distributions obtained from the SolTrace has been applied on the outer surface of the absorber using user-defined functions. Temperature-dependent emissivity, given by Eq. (11), has been considered on the outer absorber surface42,43.

The Mixed (radiation and convection) boundary condition has been considered for the outer surface of the glass cover5,17,36. Radiative heat loss was calculated using the Stefan-Boltzmann law, with the sky modeled as a vast enclosure. The sky temperature was determined using Eq. (12)44.

Convective heat loss is estimated using Newton’s law of convection. The heat transfer coefficient is derived from Eq. (13)45. The ambient temperature is considered as 298 K, and wind velocity is assumed as 2 m s-1.

The adiabatic wall boundary condition has been applied for the end surfaces of the glass cover, vacuum space, and absorber tube40.

Numerical simulation

Two separate meshes of HCE with RTA and CTA have been developed for each case, as given in Fig. 5 to perform the thermal analysis of the PTC. The meshes are structured meshes with hexahedral elements to attain accurate results with quicker convergence. To accurately resolve the high temperature and velocity gradients of the heat transfer fluid (HTF), a highly refined mesh was employed in the vicinity of the wall46. In all simulations, the value of y + is maintained below one in this region to ensure precise results.

For improved convergence and stability, a coupled algorithm was employed to integrate pressure and velocity. The second-order upwind scheme was used for discretizing the energy and momentum equations, while the PRESTO scheme was applied for pressure discretization. Turbulent kinetic energy, turbulent dissipation, and discrete ordinates were discretized using the first-order upwind scheme. All simulations were conducted with a convergence criterion for scaled residuals set to below 10–6.

Thermal, exergy and overall efficiency calculation

The thermal efficiency of a PTC is defined as the ratio of the useful heat gained by the heat transfer fluid (HTF) in the absorber to the solar irradiation incident on the aperture47. It is calculated by using Eq. (14).

The useful heat gain (Qu) has been calculated by using Eq. (15).

Since the cross-sectional area of the RTA is low, the pressure drop in the RTA is higher compared to CTA. Therefore, pumping power is an important parameter to be studied. The pumping power (Wp) is calculated using Eq. (16)48.

The exergy efficiency (ηe) is defined as the ratio of useful exergy production (Exu) to the exergy flow associated with solar irradiation (Exs), as described in Eq. (17)49. Useful exergy production is calculated using Eq. (18)47 while the exergy flow of solar irradiation (Exs) is determined using Eq. (20)50. The temperature of the sun (Tsun) is taken as 5770 K47.

The overall efficiency of the PTC has been calculated by using Eq. (21)51. The electrical efficiency (ηel) is taken as 32.7%52.

Mesh independent test and validation

To evaluate the sensitivity of the results, a mesh independence test was performed for the heat collection element (HCE) using both rhombus-shaped absorber (RTA) and circular tube absorber (CTA). The analysis identified that grids with 1,310,720 elements for the RTA and 1,351,680 elements for the CTA provided optimal results. The results of the present study have been validated by comparing them with the experimental data provided by Dudley et al.43. The numerical results are in close agreement with the experimental data, as reported in the authors’ earlier work by Donga and Kumar36.

Results and discussions

Heat flux distributions and Optical efficiency

The distribution of circumferential heat flux has been studied for both absorbers, CTA and RTA. The effect of slope error on the circumferential heat flux distribution at two rim angles (ψ = 80° and 90°) has been analyzed and results are presented in Fig. 6. (a) and (b). It is observed that distribution of circumferential heat flux is symmetrical in case of RTA and CTA. With slope error, peak heat flux decreases irrespective of the shape of absorber. But the peak heat flux obtained in RTA is higher in comparison to CTA even in presence of slope error. In absence of slope error for ψ = 80°, the value of peak flux obtained is 90,129.54 W/m2 for RTA and it is 64,530.6 W/m2 for CTA. With ψ = 90° and σ = 0 mrad, the value of peak flux is 100,477.6 W/m2 for RTA and it is 62,372.7 W/m2 for CTA. The higher peak flux observed on the RTA in comparison to the CTA, even in the presence of slope error, is primarily attributable to its flat surface and low surface area. As the rim angle increases, a slight increase in peak flux is observed in the case of RTA. The RTA’s elevated peak fluxes will generate steeper temperature gradients, resulting in increased thermal stresses. These heightened stresses have the potential to cause damage to the HCE. Therefore, the safe operating temperature range in both the absorbers have also been studied and presented in Sect. 4.2.

The average heat flux over the surface of the absorber has been estimated for both the absorbers and results are presented in Fig. 7. It is observed that average heat flux is not affected by slope error. However, higher values of average heat flux are obtained with RTA for both rim angles. It is due to improvement in the concentration of solar radiation when PTC is employed with RTA. With RTA, higher values of average heat flux are obtained at trough rim angle of 90° in comparison to rim angle of 80°. Higher average heat fluxes and peak fluxes on the RTA may result in increased thermal stress within the material. Over time, this phenomenon can induce thermal fatigue, micro-cracking, or accelerated degradation, potentially reducing the lifespan of the absorber and increasing the necessity for maintenance. Although increased average heat flux may enhance immediate performance, it could potentially compromise the long-term durability, efficiency, and maintenance requirements of the absorbers, thereby affecting their overall lifecycle cost and practical efficiency, which is beyond the scope of the current investigation.

In this study, the optical efficiencies of PTC with RTA and CTA have been estimated and compared. Optical efficiency is defined as the ratio of the energy absorbed by the absorber to the energy incident on the aperture of the PTC. The results computed have been presented in Fig. 8. It has been observed that optical efficiency is nearly the same in the case of both absorbers. However, optical efficiency decreases in the presence of slope error with both the absorbers. It can be stated that CR of PTC improves by employing RTA without affecting the optical performance. In the utilization of secondary mirrors, the improvement in CR is 73.4%; however, the energy losses due to shadow effects are approximately 6.7% for the same trough employed in this study22. The proposed rhombus-shaped design enhances the CR by 16.1% without incurring energy losses attributable to the shadow of secondary mirrors, as this design does not incorporate secondary mirrors.

Temperature gradients and pressure drop

Temperature gradients (ΔT), defined as the difference between the maximum and minimum temperatures on the absorber surface, are a crucial parameter to study for ensuring the safe operation of a PTC. The higher temperature gradients in the absorber may lead to higher thermal stresses induced in the absorber can cause deflection in the absorber. Excessive deflection in the absorber, beyond permissible limits, can damage the glass tube. Therefore, maintaining lower temperature gradients in the absorber is essential for safe operation.

The temperature gradients at middle cross-section of the RTA and CTA have been computed for rim angle of 90°. Inlet fluid temperature and volumetric flow rates have been taken as 650 K and 30 m3/h18,42 respectively. Temperature contours are illustrated in Fig. 9. The analysis reveals that temperature gradients in the rhombus-shaped absorber (RTA) are lower compared to those in the circular tube absorber (CTA). Despite RTA exhibiting a higher peak flux (as shown in Fig. 6), the temperature gradients are reduced due to higher fluid velocities resulting from the smaller cross-sectional area36. Temperature gradients are not affected at all in the presence of slope error. At σ = 0 mrad, the temperature gradients (ΔT) obtained for RTA and CTA are 19.9 K and 30 K respectively. The values of ΔT for RTA and CTA are 19.4 K and 29 K, respectively when σ = 2.5 mrad. It can be interpreted that RTA will have lower induced thermal stresses hence smaller deflections. RTA can be safer in operation in comparison to CTA. However, the range of thermal stress for safe operation needs to be worked upon for RTA and CTA by conducting Finite Element Analysis, which is not in the scope of present work.

The temperature gradient (ΔT) variation with the volumetric flow rate of the fluid for both absorbers has been analyzed, considering slope error, as illustrated in Fig. 10a and b. The plots correspond to rim angles of 80° and 90°, respectively. Inlet fluid temperature has been taken equal to 600 K. It has been observed that the value of ΔT for RTA is lower than CTA for the range of flow rate considered in this study. The value of ΔT decreases for both absorbers as the flow rate increases, attributed to the enhanced heat transfer associated with higher fluid velocities. The plots reveal that temperature gradients remain unchanged in the presence of slope error for the rhombus-shaped absorber (RTA). However, for CTA, the temperature gradients are slightly higher with zero slope error. It is because of higher peak flux in CTA in absence of slope error as presented in Fig. 6.

Pressure drop in the fluid flow is an important parameter to be studied in PTC for pumping power requirement. Figure 11 illustrates the variation of pressure drop with volumetric flow rate for both the rhombus-shaped absorber (RTA) and the circular tube absorber (CTA). It is observed that the pressure drop increases with flow rate and is higher in the RTA compared to the CTA. The smaller cross-sectional area gives higher fluid velocities for a given flow rate hence higher pressure drop is in RTA. For CTA, the pressure drop is higher when rim angle is 800. With ψ = 80°, the pressure drops in RTA are higher than CTA by 445% and 468.7% for the flow rates of 200 l/min and 600 l/min, respectively. When ψ = 90°, the pressure drops in RTA are higher by 954% and 1114.5% for the flow rates of 200 l/min and 600 l/min, respectively.

Collector efficiencies

Thermal efficiency

Thermal efficiency for both absorbers was computed across a range of inlet temperature by considering slope error. Inlet temperature is varied in range 400 to 650 K, while the flow rate was maintained constant at 30 m3/hr18,36,42. Computations has been done for PTC with rim angles of 80° and 90° respectively. The values obtained for thermal efficiency have been plotted in Figs. 12(a) and (b). It is shown that thermal efficiency of PTC decreases with increase in inlet fluid temperature in both absorbers. And thermal efficiency also decreases in presence of slope error for CTA and RTA. However, higher values of thermal efficiency of PTC are obtained in case of RTA for all the cases examined in present study. It is because of the greater average heat flux obtained over the surface of the RTA and reduced heat losses from the surface of the RTA due to its smaller size. Also, higher fluid velocities in the RTA due to its lower cross-sectional area lead to an improvement in the heat transfer between the absorber surface and HTF. All these factors cumulatively aid to enhancement of the thermal efficiency of the PTC with RTA. It has been observed that at inlet fluid temperature of 400 K, Fig. 12 (a), The thermal efficiency of the PTC equipped with a rhombus-shaped absorber (RTA) with a rim angle of 80° shows an improvement of up to 0.28% in the absence of slope error and up to 0.52% with a slope error of 2.5 mrad. At an inlet temperature of 650 K, the thermal efficiency of the PTC with RTA exceeds that of the circular tube absorber (CTA) by up to 1.73% and 2.28% for slope errors of 0 and 2.5 mrad, respectively. With rim angle of 90°, improvement in thermal efficiency of PTC with RTA in reference to CTA is almost same as obtained when rim angle is 80°. The results indicate a significant performance enhancement of the PTC with the rhombus-shaped absorber (RTA) when the fluid inlet temperature is set to 650 K, which closely approximates the operating temperature of a typical PTC power plant.

Exergy efficiency

Exergy efficiency of a thermodynamic system indicates the amount of available energy converted into useful work. In present work, exergy efficiency of PTC with CTA and RTA has been calculated. Figures 13a and b illustrate the variation in exergy efficiency (ηe) of the PTC with inlet fluid temperature for both absorbers, with rim angles of 80° and 90°, respectively. Slope error has also been considered. It can be seen from Fig. 13a and b that exergy efficiency of PTC increases with increase in inlet fluid temperature in case of CTA and RTA. The impact of slope error on exergy efficiency is minimal for both the circular tube absorber (CTA) and the rhombus-shaped absorber (RTA). Exergy efficiency is dependent not only on optical concentration but also on thermal losses, fluid properties, and heat transfer, as delineated in Eqs. (18) to (20). Minor optical losses resulting from slope error are frequently less significant in their impact on exergy efficiency compared to more substantial thermal losses within the system, particularly at elevated operating temperatures. Additionally, the exergy efficiency of the PTC with RTA shows consistent improvement compared to that of the CTA across all cases examined in this study. It can be stated that the exergetic performance of the PTC improves with RTA despite of higher pressure drop in RTA. With ψ = 80° (Fig. 13a), and Tin = 650 K, the improvement in the exergy efficiency of the PTC with RTA (in reference to the CTA) in presence of slope error (σ = 2.5 mrad) is found to be 1.33%. For the case of ψ = 90° (Fig. 13b), at Tin = 650 K, the improvement in the exergy efficiency of PTC with RTA is 2.84% and 1.64% with σ = 0 and σ = 2.5 mrad, respectively.

Overall efficiency

Figures 14a and b present a comparison of overall collector efficiency (ηo) for (RTA) and (CTA), with rim angles of 80° and 90°, respectively. A significant improvement in the overall efficiency has been observed with RTA at Tin = 650 K (typical operating temperature of PTC power plant). In absence of slope error, with ψ = 80° and Tin = 650 K, the useful heat gain obtained with RTA is 846.25 W higher than that obtained with CTA. However, the pumping work requirement with RTA is 61.86 W (total power is 189.17 W at electrical efficiency of 32.7% of pump) higher than the power requirement with CTA. It indicates improvement in the overall thermal performance of the PTC with RTA. As observed from Fig. 14a, for the case of ψ = 80°, Tin = 650 K, the improvement in the overall efficiency of the PTC with RTA in comparison to CTA is found to be 1.41% and 1.81% in absence and presence of slope error respectively. In the case of ψ = 90° (Fig. 14 b), at Tin = 650 K, the overall efficiency of the collector with the rhombus-shaped absorber (RTA) is observed to increase by 2.46% in the absence of slope error and by 1.49% with a slope error of 2.5 mrad.

Conclusions

This study investigates the potential for enhancing the overall performance of a PTC by using a rhombus-shaped absorber instead of the traditional circular tube absorber. The performance of the PTC was assessed with both the circular tube absorber (CTA) and the rhombus-shaped absorber (RTA) to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of these designs. The optical analysis using ray-tracing simulations and thermal analysis employing the finite volume method. The performance of the PTC with both circular tube absorber (CTA) and rhombus-shaped absorber (RTA) was compared by evaluating thermal efficiency, exergy efficiency, and overall efficiency. The results are presented for rim angles of 80° and 90°, with fluid flow rates ranging from 200 to 600 L/min, inlet temperatures varying from 400 to 650 K, and slope errors considered from 0 to 2.5 mrad.

The analysis reveals that the rhombus-shaped absorber (RTA) achieves a higher average heat flux due to its greater CR. However, peak flux decreases with increasing slope error for both types of absorbers. Additionally, the change in optical efficiency is minimal when the circular tube absorber (CTA) is replaced by the RTA. Consequently, it can be concluded that the CR of the PTC is enhanced without compromising optical efficiency when using the RTA.

Results have shown that temperature gradients obtained on the surface of RTA are lower than those obtained on surface of CTA. Hence, RTA may be safer in operation than CTA due to lower induced thermal stresses. It was found that the thermal efficiency of the PTC significantly improves with the rhombus-shaped absorber (RTA). Specifically, the thermal efficiency increased by up to 2.88% at an inlet temperature of 650 K and a rim angle of 80°, compared to the conventional tubular absorber, even in the presence of slope error.

From the results presented, a significant rise in the pressure drop and subsequently more pumping work requirement has been found with RTA. But there is improvement in exergy efficiency and overall efficiency of the PTC with RTA in comparison to CTA for same operating conditions. It has been found that improvement in the exergy efficiency of PTC with RTA having rim angle of 800 is up to by 1.45% and improvement in overall efficiency is up to by 1.40% at same operating conditions of inlet fluid temperature 650 K, in presence of slope error (conditions approximating field conditions). However, the values of efficiencies increase marginally in absence of slope error. The overall efficiency indicates net conversion of incident solar radiation into useful heat by taking care of thermal energy equivalent to pump work. It can be concluded that the overall thermal performance of the PTC improves by employing rhombus shaped absorber.

Rhombus shaped absorber can be employed with PTC without any change in the trough shape and size. It can be fixed in the evacuated glass tube with slight modifications of end seals. The practical challenges regarding manufacturing of rhombus tube absorber and its installation into the PTC are yet to be explored.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are included in the article. Additional data can be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- Am :

-

Area of the mirror (mm2)

- Aa :

-

Area of the absorber surface (mm2)

- cp :

-

Specific heat of HTF (J kg-1 K-1)

- CRc:

-

Concentration ratio of PTC with circular tube absorber

- CRr:

-

Concentration ratio of PTC with rhombus tube absorber

- dato :

-

Outer diameter of absorber tube (mm)

- dgti :

-

Inner diameter of glass tube (mm)

- dgto :

-

Outer diameter of glass tube (mm)

- Exu :

-

Useful exergy production

- Exs :

-

Exergy flow of the solar irradiation

- F:

-

Focal length (m)

- h:

-

Heat transfer coefficient (W m-2 K-1)

- L:

-

Length of the receiver (m)

- \(\dot{m}\) :

-

Mass flow rate of HTF (kg s-1)

- ΔP:

-

Pressure drop (Pa)

- q:

-

Average heat flux over the absorber tube (W m-2)

- r:

-

Radius of the circular absorber (mm)

- S:

-

Side length of the rhombus (mm)

- Ta :

-

Ambient air temperature (K)

- Tao :

-

Surface temperature of absorber (K)

- Tfm :

-

Mean fluid temperature (K)

- Tin :

-

Average inlet temperature of HTF (K)

- Tout :

-

Average outlet temperature of HTF (K)

- Tsky :

-

Sky temperature (K)

- Tsun :

-

Temperature of the sun (K)

- ΔT:

-

Peripheral temperature difference in the absorber (K)

- Vw :

-

Wind velocity (m s-1)

- Qu :

-

Useful heat gain by HTF (W)

- w:

-

Aperture width (m)

- Wp :

-

Pumping power (W)

- αat :

-

Absorber absorbance

- εao :

-

Absorber emittance

- ρm :

-

Concentrator reflectance

- ρ:

-

Density of the HTF (kg/m3)

- ρfm :

-

Mean density (kg/m3)

- σ:

-

Slope error (mrad)

- θ:

-

Half acceptance angle (o)

- ψ:

-

Rim angle (o)

- τgt :

-

Glass cover transmittance

- ηe :

-

Exergy efficiency

- ηel :

-

Electrical efficiency

- ηo :

-

Overall efficiency

- ηt :

-

Thermal efficiency

- CR:

-

Concentration ratio

- CTA:

-

Circular tube absorber

- DNI:

-

Direct normal irradiation

- HTF:

-

Heat transfer fluid

- HCE:

-

Heat collection element

- PTC:

-

Parabolic trough collector

- RTA:

-

Rhombus tube absorber

References

Ilyas, S. U., Pendyala, R., Narahari, M. & Susin, L. Stability, rheology and thermal analysis of functionalized alumina- thermal oil-based nanofluids for advanced cooling systems. Energy Convers. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2017.01.079 (2017).

Yazdanifard, F., Ebrahimnia-Bajestan, E. & Ameri, M. Performance of a parabolic trough concentrating photovoltaic/thermal system: Effects of flow regime, design parameters, and using nanofluids. Energy Convers Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2017.06.075 (2017).

Abdulhamed, A. J., Adam, N. M., Ab-Kadir, M. Z. A. & Hairuddin, A. A. Review of solar parabolic-trough collector geometrical and thermal analyses, performance, and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.04.085 (2018).

Emani, S. et al. Effects of wavy structure, ambient conditions and solar intensities on flow and temperature distributions in a mini solar flat plate collector using computational fluid dynamics. Engineering Applications of Computational Fluid Mechanics https://doi.org/10.1080/19942060.2023.2236179 (2023).

Ghomrassi, A., Mhiri, H. & Bournot, P. Numerical study and optimization of parabolic trough solar collector receiver tube. J. Solar Energy Eng. Trans. ASME https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4030849 (2015).

Jebasingh, V. K. & Herbert, G. M. J. A review of solar parabolic trough collector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.043 (2016).

Hafez, A. Z. et al. Design analysis of solar parabolic trough thermal collectors. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.09.010 (2018).

Price H, Lu¨pfert E, Kearney D, Zarza E, Cohen G, Gee R, et al. Advances in Parabolic Trough Solar Power Technology. J. Sol Energy Eng., https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1467922. (2002).

Jha, P., Das, B. & Gupta, R. Energy matrices evaluation of a conventional and modified partially covered photovoltaic thermal collector. Sustain. Energy Technologies and Assessments https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2022.102610 (2022).

Jha, P., Das, B., Gupta, R., Mondol, J. D. & Ehyaei, M. A. Review of recent research on photovoltaic thermal solar collectors. Solar Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2023.04.004 (2023).

Tzivanidis, C., Bellos, E. & Antonopoulos, K. A. Energetic and financial investigation of a stand-alone solar-thermal Organic Rankine Cycle power plant. Energy Convers Manag https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2016.08.033 (2016).

Loni, R., Kasaeian, A. B., Mahian, O. & Sahin, A. Z. Thermodynamic analysis of an organic rankine cycle using a tubular solar cavity receiver. Energy Convers Manag https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2016.09.007 (2016).

Mwesigye, A., Huan, Z. & Meyer, J. P. Thermal performance and entropy generation analysis of a high concentration ratio parabolic trough solar collector with Cu-Therminol®VP-1 nanofluid. Energy Convers Manag https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2016.04.106 (2016).

Hoseinzadeh, H., Kasaeian, A. & Behshad, S. M. Geometric optimization of parabolic trough solar collector based on the local concentration ratio using the Monte Carlo method. Energy Convers Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2018.09.001 (2018).

Khanna, S. & Sharma, V. Explicit Analytical Expression for Solar Flux Distribution on an Undeflected Absorber Tube of Parabolic Trough Concentrator Considering Sun-Shape and Optical Errors. J. Solar Energy Eng. Trans. ASME https://doi.org/10.1115/14032122 (2016).

Khanna, S., Kedare, S. B. & Singh, S. Analytical expression for circumferential and axial distribution of absorbed flux on a bent absorber tube of solar parabolic trough concentrator. Solar Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2013.02.020 (2013).

Zhao, D. et al. Influences of installation and tracking errors on the optical performance of a solar parabolic trough collector. Renew. Energy 94, 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2016.03.036 (2016).

Mwesigye, A., Huan, Z., Bello-Ochende, T. & Meyer, J. P. Influence of optical errors on the thermal and thermodynamic performance of a solar parabolic trough receiver. Solar Energy 135, 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2016.06.045 (2016).

Güven, H. M. & Bannerot, R. B. Derivation of universal error parameters for comprehensive optical analysis of parabolic troughs. J. Solar Energy Eng. Trans. ASME 108, 275–281. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3268106 (1986).

Meiser, S., Schneider, S., Lüpfert, E., Schiricke, B. & Pitz-Paal, R. Evaluation and assessment of gravity load on mirror shape and focusing quality of parabolic trough solar mirrors using finite-element analysis. Appl. Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.04.045 (2017).

Donga, R. K., Kumar, S. & Kumar, A. Performance Evaluation of Parabolic Trough Collector with Receiver Position Error. J. Thermal Eng. https://doi.org/10.18186/THERMAL.849869 (2021).

Rodriguez-Sanchez, D. & Rosengarten, G. Improving the concentration ratio of parabolic troughs using a second-stage flat mirror. Appl. Energy 159, 620–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.08.106 (2015).

Bakos, G. C., Ioannidis, I., Tsagas, N. F. & Seftelis, I. Design, optimisation and conversion-efficiency determination of a line-focus parabolic-trough solar-collector (PTC). Appl. Energy 68, 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-2619(00)00034-9 (2000).

Wirz, M., Petit, J., Haselbacher, A. & Steinfeld, A. Potential improvements in the optical and thermal efficiencies of parabolic trough concentrators. Solar Energy 107, 398–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2014.05.002 (2014).

Gee R, Cohen G, Winston R. A Nonimaging Receiver for Parabolic Trough Concentrating Collectors 269–76. https://doi.org/10.1115/sed2002-1062. (2009).

Highlands, N. Applied Optics Letters to the Editor. Appl. Opt. 21, 571–572 (1982).

McIntire, W. R. Secondary concentration for linear focusing systems: a novel approach. Appl. Opt 19, 3036–3037. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.19.003036 (1980).

Canavarro, D., Chaves, J. & Collares-Pereira, M. New second-stage concentrators (XX SMS) for parabolic primaries; Comparison with conventional parabolic trough concentrators. Solar Energy 92, 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOLENER.2013.02.011 (2013).

Canavarro, D., Chaves, J. & Collares-Pereira, M. New Optical Designs for Large Parabolic Troughs. Energy Proc. 49, 1279–1287. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EGYPRO.2014.03.137 (2014).

Gordon, J. M. & Feuermann, D. Optical performance at the thermodynamic limit with tailored imaging designs. Appl. Opt. 44, 2327–2331. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.44.002327 (2005).

Ostroumov, N., Gordon, J. M. & Feuermann, D. Panorama of dual-mirror aplanats for maximum concentration. Appl. Opt. 48, 4926–4931. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.48.004926 (2009).

Collares-Pereira, M., Gordon, J. M., Rabl, A. & Winston, R. High concentration two-stage optics for parabolic trough solar collectors with tubular absorber and large rim angle. Solar Energy 47, 457–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-092X(91)90114-C (1991).

Omer, S. A. & Infield, D. G. Design and thermal analysis of a two stage solar concentrator for combined heat and thermoelectric power generation. Energy Convers Manag. 41, 737–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-8904(99)00134-X (2000).

Donga, R. K. & Kumar, S. Parabolic trough collector with rhombus tube absorber for higher concentration ratio. Energy Sources Part A: Recovery Util. Environ. Effects 40, 2620–2631. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2018.1505981 (2018).

Wendelin, T. SolTRACE: a new optical modeling tool for concentrating solar optics. Solar Energy. https://doi.org/10.1115/isec2003-44090. (2003).

Donga, R. K. & Kumar, S. Thermal performance of parabolic trough collector with absorber tube misalignment and slope error. Solar Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2019.04.007 (2019).

Donga, R. K. Heat transfer enhancement in absorber tube of parabolic trough solar collector using longitudinal curved fins. JP J. Heat Mass Transfer. https://doi.org/10.17654/HM022010021 (2021).

Jeter, S. M. Calculation of the concentrated flux density distribution in parabolic trough collectors by a semifinite formulation. Solar Energy 37, 335–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-092X(86)90130-1 (1986).

Bellos, E., Tzivanidis, C. & Tsimpoukis, D. Thermal, hydraulic and exergetic evaluation of a parabolic trough collector operating with thermal oil and molten salt based nanofluids. Energy Convers. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2017.11.051 (2018).

Cheng, Z. D., He, Y. L., Cui, F. Q., Xu, R. J. & Tao, Y. B. Numerical simulation of a parabolic trough solar collector with nonuniform solar flux conditions by coupling FVM and MCRT method. Solar Energy 86, 1770–1784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2012.02.039 (2012).

He, Y. L., Xiao, J., Cheng, Z. D. & Tao, Y. B. A MCRT and FVM coupled simulation method for energy conversion process in parabolic trough solar collector. Renew Energy 36, 976–985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2010.07.017 (2011).

Forristall R. Heat Transfer Analysis and Modeling of a Parabolic Trough Solar Receiver Implemented in Engineering Equation Solver. United States, (2003).

Dudley Albuquerque, NM (United States)] VE [EG&G SP, Kolb GJ, Mahoney AR, Mancini TR, Matthews Albuquerque, NM (United States)] CW [Sandia NLabs, Sloan Austin, TX (United States)] M [Sloan SE, et al. Test results: SEGS LS-2 solar collector. United States: https://doi.org/10.2172/70756. (1994).

Swinbank, W. C. Long-wave radiation from clear skies. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 89, 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.49708938105 (1963).

Mullick, S. C. & Nanda, S. K. An improved technique for computing the heat loss factor of a tubular absorber. Solar Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-092X(89)90124-2 (1989).

Jha, V., Velidi, G. & Emani, S. Optimization of flame stabilization methods in the premixed microcombustion of hydrogen–air mixture. Heat Transfer https://doi.org/10.1002/htj.22574 (2022).

Bellos, E. & Tzivanidis, C. A detailed exergetic analysis of parabolic trough collectors. Energy Convers Manag. 149, 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENCONMAN.2017.07.035 (2017).

Bellos, E. & Tzivanidis, C. Investigation of a star flow insert in a parabolic trough solar collector. Appl. Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.04.099 (2018).

Bellos, E., Tzivanidis, C., Daniil, I. & Antonopoulos, K. A. The impact of internal longitudinal fins in parabolic trough collectors operating with gases. Energy Convers. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2016.12.057 (2017).

Petela, R. Exergy of undiluted thermal radiation. Solar Energy 74, 469–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-092X(03)00226-3 (2003).

Bellos, E. & Tzivanidis, C. Investigation of a star flow insert in a parabolic trough solar collector. Appl. Energy 224, 86–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.04.099 (2018).

Mwesigye, A., Huan, Z. & Meyer, J. P. Thermodynamic optimisation of the performance of a parabolic trough receiver using synthetic oil-Al2O3 nanofluid. Appl. Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.07.035 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of UPES for this research and providing access to campus facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.K.D. contributed to methodology, software development, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing the original draft, and project administration. S. K. conceptualization, review and editing. G.V. was responsible for conceptualization, validation, and writing – review and editing. Both authors wrote the main manuscript text and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of generative AI in scientific writing

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used Chat GPT 3.5 in order to correct grammar and language editing. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Donga, R.K., Kumar, S. & Velidi, G. Numerical investigation of performance and exergy analysis in parabolic trough solar collectors. Sci Rep 14, 31908 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83219-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83219-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Heat transfer enhancement in a parabolic trough collector using finned tubular absorber

Scientific Reports (2025)