Abstract

The emergence of self-propelling magnetic nanobots represents a significant advancement in the field of drug delivery. These magneto-nanobots offer precise control over drug targeting and possess the capability to navigate deep into tumor tissues, thereby addressing multiple challenges associated with conventional cancer therapies. Here, Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox, a novel self-propelling magnetic nanobot conjugated with a biocompatible protein surface and loaded with doxorubicin for the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), is reported. The self-propulsion of magnetic nanobots occurs due to a catalytic interaction between Fe3O4 nanoparticles and hydrogen peroxide. This interaction results in generation of O2 bubbles and high-speed propulsion in blood serum. Cell entry kinetic studies confirmed higher internalization of the drug into TNBC cells with Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots, resulting in a lower observed IC50 and higher potential to kill cancer cells compared to free doxorubicin. Moreover, fluorescence imaging studies confirmed an increase in the production of reactive oxygen species, leading to maximum cellular damage. Endocytosis studies elucidate the mechanism of cellular internalization, revealing clathrin-mediated endocytosis, while the cell cycle study demonstrates significant cell cycle arrest in the G2-M phase. Thus, the designed protein-conjugated self-propelling magnetic nanobots have the potential to develop into a novel drug delivery platform for clinical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past decade, significant advancements have been achieved in the field of micro-nano motors, particularly in improving drug delivery, diagnostics, and other biomedical applications1,2. In contrast to conventional nanoparticles, self-propelled nano drug delivery systems effectively address numerous challenges arising from motion and viscosity in biological fluids345. Moreover, these systems provide several advantages, including their remarkable ability to traverse biological membranes and penetrate deeply into tissues or tumors6, functionalization facilitating high drug loading with a controlled and responsive drug release profile7,8, and navigation of speed and direction through external fields, such as magnets9, ultrasound10, or temperature gradients, among others11. The integration of micro-nano motors with complementary strategies, such as photothermal12, ultrasound13, photodynamic14, and oxidative stress15, demonstrates a synergistic effect, imparting further benefits in therapeutics and thereby opening up new avenues for effective treatment.

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) stands out as one of the most aggressive types of breast cancer16,17, distinguished by an elevated risk of relapse18and brain metastasis19, resulting in notably short survival periods20(typically 3 to 4 months). Moreover, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) presents a significant challenge due to drug resistance, including efflux-mediated reductions in intracellular drug concentrations, which consequently diminish therapeutic efficacy21. This represents an unmet and urgent need for a promising drug delivery system for TNBC.

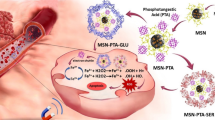

We design novel magnetic nanobots by conjugating plasma proteins with Fe3O4 nanoparticles for the efficient delivery of anticancer drugs. The chemical bonding of plasma proteins establishes a biocompatible surface, providing an expansive chemical space for drug loading and conjugation. This functionalized surface also facilitates accessibility to various biomacromolecules, such as albumin and transferrin, enhancing tumor-targeting capabilities and receptor-mediated drug entry. Fe3O4-based nanobots autonomously propel in biologically relevant media, including human blood serum, due to the O2 bubbles produced from the reaction between Fe3O4 nanoparticles and H2O2(Fenton reaction)22, imparting dynamic functionality to this nano-system. Additionally, the elevated levels of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) produced by cancer cells (approximately 0.5 nmol/104 cells/h)23contribute to increase in oxidative stress, leading to cancer cell death24.

In this study, novel Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots are synthesized through sequential conjugation reactions involving glutathione (GSH), plasma proteins, and doxorubicin onto Fe3O4 nanoparticles via EDC/NHS coupling reactions. These functionalized nanobots demonstrate controlled and pH-responsive release of doxorubicin that can effectively reduce nonspecific drug release and associated toxicities. The nanobots exhibit faster propulsion speeds, resulting in higher forces for deeper penetration into tumor tissues. Moreover, the designed system shows remarkable cellular uptake, leading to rapid and increased nuclear accumulation of doxorubicin compared to free drug, offering a significant advantage in overcoming drug resistance and demonstrating efficient cytotoxicity. The cellular internalization mechanism of nanobots is further elucidated using internalization receptor inhibitors to confirm clathrin-mediated endocytosis.

Moreover, a study using the DCFH-DA fluorescent probe to analyse reactive oxygen species demonstrates the potential of nanobots to generate substantial ROS species, ultimately leading to cancer cell death. While the cell cycle analysis reveals that the nanobots induce maximum cell arrest in the G2-M phase, aligning with the mechanism of action of doxorubicin. Therefore, the proposed self-propelling, protein-conjugated, magnetic nanobots demonstrate a promising anticancer activity, presenting a potential drug delivery system for TNBC.

Results and discussion

Design and synthesis of protein bound magnetic nanobots and characterization

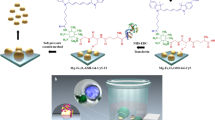

The multicomponent Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots were designed and synthesized through a systematic stepwise process (Fig. 1). Initially, Fe3O4 nanoparticles were prepared via the coprecipitation of ferric and ferrous ions using an aqueous ammonia solution. Subsequently, glutathione (GSH) was conjugated onto the surface of Fe3O4 to introduce amino and carboxyl functional groups, followed by binding with serum proteins, resulting in protein-decorated Fe3O4nanoparticles. Finally, Doxorubicin (DOX) was coupled with the activated carboxyl groups of proteins to yield Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots (Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (C)). Unconjugated DOX was presumed to be entrapped within the protein matrix via non-covalent interactions25, denoted as Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A). It is hypothesized that the conjugation of proteins not only provides a larger chemical surface to increase drug loading but also enables proteins such as albumin and transferrin to serve as targeting moieties26. Furthermore, the Fe3O4nanoparticles plays pivotal role in magnetic navigation27, self-propulsion6, and the generation of reactive cytotoxic oxidative radicals28. The morphology of the Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots was studied using Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), revealing their spherical nature with an average diameter of approximately 20 nm (Fig. 2A). High-Resolution TEM (HRTEM) images indicated a magnetic crystalline nature, displaying lattice fringes with a plane-to-plane separation of 0.29 nm corresponds to 220 planes. (Fig. 2B), representing the structure of magnetite planes29. The Selected Area Electron Diffraction (SAED) pattern exhibited crystalline quality, with spotty diffraction rings and well-resolved spots (Fig. 2C), confirming the structural features of Fe3O4 in the Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of Fe3O4 (a), Fe-GSH (b), Fe-GSH-Protein (c), and Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (d) were analysed to characterize the conjugation reactions with GSH, protein, and DOX (Fig. 2D). Spectrum (a) of Fe3O4 exhibited a characteristic peak at 574 cm−1corresponding to Fe-O stretching30, while spectrum (b) of Fe-GSH displayed an additional peak at 1654 cm−1 corresponding to C = O stretching of amides, confirming the conjugation of GSH with Fe3O4. Spectrum (c) of Fe-GSH-Protein showed peak at 3275 cm−1 corresponding to N-H stretching of primary NH2groups. Furthermore, spectrum (d) of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox showed all the peaks observed in spectra6 (a), (b), and (c), along with additional peaks of primary NH2 at 3696 cm−1 and characteristic amide C = O stretching at 1654 cm−1. These sequential changes in the spectrum pattern of IR indicate the successful conjugation of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox. Zeta potential studies also support the characterization of these reactions, as evidenced by the changes observed in the zeta potential values obtained after each reaction step. The mean zeta potential values obtained were − 1.1 for Fe3O4, −28.1 for Fe-GSH, −42.4 for Fe-GSH-Protein, and − 44.1 for Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (Fig. 2E). The conjugation/loading of DOX in Fe-GSH-Protein was confirmed using UV-visible spectrophotometry. The UV spectra of Fe, Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox, and DOX were analysed, revealing a characteristic λmax of 480 nm for Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots, confirming the presence of DOX31 (Fig. 2F). The conjugation of protein with Fe-GSH nanobots was confirmed using the Biuret test (Fig. 2G). This colorimetric test demonstrated the presence of protein in the Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox sample by changing the color of the solution to a deep purple, that matching with the color of standard protein sample. In contrast, the sample containing only Fe3O4 nanoparticles showed a negative reading with a faint blue color.

(A) Schematic representation of the mechanism behind the O2 bubble-induced autonomous propulsion of the protein bound nanobot, followed by (B)an illustration showing the targeting of the nanobot to the endocytosis receptor and its entry into the cancer cell. Finally, the mechanism of triggered drug release under intracellular endo/lysosomal conditions. (C) Schematic illustration representing the step-by-step synthesis of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox.

Characterization of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox: (A) TEM images of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox, (B) showing the Fe3O4 structure, and (C) the crystalline nature of the nanoparticles. (D) FTIR spectra of Fe3O4 (a), Fe-GSH (b), Fe-GSH-Protein (c), and Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (d).(E) Changes in surface charge of nanomaterials due to the conjugation reactions of Fe3O4, Fe-GSH, Fe-GSH-Protein, and Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox. (F) UV-visible spectra of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox matching the standard DOX (λmax = 484 nm). (G) Colorimetric test (Biuret test) demonstrating the presence of protein in the Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox sample by changing the solution color to deep purple, matching the color of the standard protein sample (HSP).

Drug release profiles of the nanobots

To evaluate the impact of pH on the release profile of DOX from Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox, we conducted a drug release study at pH 7.4 (blood pH) and pH 5 (lysosomal pH). The results illustrated a pH-responsive controlled release of DOX (Fig S1), showing an increase in both rate and quantity of drug release under acidic conditions, approximately ~ 61% at pH 5 after 48 h compared to around ~ 38% at pH 7.4. Furthermore, maximum drug release of approximately 88% and 52% was observed after 120 h for pH 5 and pH 7.4, respectively. The higher drug release at acidic pH is attributed to the degradation of amide linkages between DOX and Fe-GSH-Protein (Fig. 1B). This controlled and pH-responsive drug release profile of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots holds particular significance for cancer treatment, aiming to prevent burst release of cytotoxic drugs into the systemic circulation while achieving controlled release within the cancer microenvironment or lysosomes. This approach can thereby reduce toxicity and enhance the potency of anticancer drugs32.

Motion and position-kinetic analysis of nanobots

The propulsion mechanism involves the generation of O2 bubbles through a reaction between Fe3O4 and H2O2 (Fenton reaction). The tumor microenvironment contains H2O2with an approximate concentration23of 0.5 nmol/104 cells/h, which after reacting with Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots, can make it active and dynamic. To analyse the effect of H2O2 on O2 bubble generation, and consequently on propulsion speed and force, we examined the propulsion of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots in various concentrations of H2O2 (0%, 0.1%, 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%) in both PBS and blood serum. The results demonstrated that the vertical speed of the nanobots increases in PBS and blood serum with an increase in H2O2 concentrations, generating significant upward driving force. These studies helped us understand the propulsion behaviour, kinetics, and force of the nanobots. The propulsion pattern of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots demonstrated vertical motion in an almost straight direction followed by a downward movement (Video S1 and S2). This up-and-down motion occurs multiple times depending on their catalytic reaction with H2O2 (Fig. 3A and B). Additionally, the nanobots were evaluated for their magnetic properties, demonstrating efficient magnetic effects for controlling the position and direction of these propelling system (Fig. S2 A & B, Video S3). The average speed for upward propulsion of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots at concentrations of 0.1%, 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8% of H2O2 in PBS were 3.16, 3.30, 3.56, 6.82, 10.74, 11.14 and 12.84 mm/s respectively. While in serum, the corresponding speeds were 4.98, 8.19, 13.55, 16.73, 17.68, 20.08 and 22.22 mm/s respectively (Fig. 3A, B and C). These studies revealed that the nanobots propelled significantly faster in serum than in PBS, with speeds 2–3 times higher, as shown in Fig. 3C and Video S1 and S2. This enhanced speed is likely due to the reaction between H₂O₂ and adsorbed catalase enzymes in the serum, which increases O₂ bubble generation and oxidation processes. These reactions promote protein aggregation, setting off a cascading effect that facilitates the binding of other serum proteins, including catalase, to the surface of the protein-coated nanoparticles. This synergistic interaction further accelerates the nanobots’ propulsion in serum compared to PBS6. Similarly, the driving force of nanobots was significantly higher in serum (9.02, 24.55, and 31.9 nN) compared to PBS (5.72, 12.35, and 19.46 nN for 0.1%, 2%, and 4% H2O2 respectively) (Fig. 3D). The drag force F = 6πµrv, where v is the speed, r is the radius of the nanobot, and µ is the viscosity of the medium. Thus, the excellent speed and force of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots provide an added advantage for rapid propulsion and deep tumor penetration6.

Time-lapse images of the nanobot driven by oxygen bubble propulsion at time intervals of 0, 0.6, 1.2, and 1.8 s in PBS (A) and 0, 0.3, 0.6, and 0.9 s in serum (B) with 4% H2O2. Speed of the nanobot in the presence of different concentrations of H2O2 (0.1–8 w/v %) in PBS and serum (C). Analysis of the force of the nanobot in PBS and serum in the presence of different concentrations of H2O2 (0.1–8 w/v %) (D).

Cytotoxicity assay

Both the MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cell lines chosen for these studies represent highly invasive human breast cancer cell lines and serve as optimal models for late-stage triple-negative breast cancer33. The MTT assay revealed a decrease in cell viability in both the MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cell lines, with effects dependent on time and concentration for Fe, Fe-GSH, Fe-GSH-Protein, Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A), Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (C), and free DOX, as detailed in Supplementary Table 1. The cytotoxicity of Fe, Fe-GSH, and Fe-GSH-Protein was notably low. However, Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) exhibited the most significant cytotoxic impact, followed by Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (C), in comparison to free DOX. Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) demonstrated an IC50 of 6.30 µg/mL after 24 h of treatment on MDA-MB-231 cell lines, whereas free DOX and Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (C) showed IC50 values of 9.63 µg/mL and 8.52 µg/mL, respectively, under the same conditions. Similarly, after 48 h of treatment on MDA-MB-231 cell lines, the IC50 for Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) was 4.2 µg/mL, while free DOX and Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (C) exhibited IC50 values of 7.90 µg/mL and 6.23 µg/mL, respectively (Fig. 4C and D). For 4T1 cell lines, Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) displayed IC50 values of 7.63 µg/mL and 5.20 µg/mL after 24 h and 48 h of treatment, respectively, as depicted in Fig. 4A and B. The increased internalization of the drug and longer accumulation time resulted in lower IC50 for Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) and Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (C) compared to free drug.

Anticancer activity of Fe, Fe-GSH, Fe-GSH-Protein, Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A), Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (C), and Dox by MTT assay. MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cells were treated with Dox at a concentration range of 3.5 to 200 µg/mL (n = 3). The IC50 value of Fe, Fe-GSH, Fe-GSH-Protein, Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A), Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (C), and Dox for cultured 4T1 (A, B) and MDA-MB-231 (C, D) cells at 24 h and 48 h.

Cellular uptake study

To evaluate the cellular internalization of free DOX and Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) in MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cells, confocal fluorescence imaging and flow cytometry techniques were used. Over the course of 1 to 4 h, the red fluorescence intensity for both free Dox and Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) were increased, indicating time-dependent cellular absorption of drug in both the cell lines (4T1 and MDA-MB-231) (Figs. 5A and 6A). Notably, in cells targeted with Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A), a distinct, bright red fluorescence was observed in the cytoplasm and nuclei, suggesting rapid internalization of the nanobots. Flow cytometry studies further confirmed this trend, showing a time-dependent increase in fluorescence in both cell lines, as evidenced by the shift in the peak and increment in mean fluorescence intensity (Figs. 5B and 6B). The flow cytometry findings indicated that after 1 h, Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) nanobots demonstrated higher internalization compared to free Dox. Moreover, after 4 h, a higher amount of Dox was internalized in the nucleus by the nanobots compared to free Dox. This finding underscores the potential of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) nanobots for targeting and facilitating nuclear accumulation of the drug. While the lower accumulation of free Dox in the nucleus after 4 h could be attributed to cellular efflux mechanisms, leading to drug resistance34. Thus, the proposed Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) nanobots not only have the capability to enhance drug internalization but also hold promise for overcoming efflux-mediated drug resistance.

Cellular internalization study of free Dox and Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) in 4T1 cells and the results were observed after 1 and 4 h of incubation (A).The histogram and a bar graph were used to demonstrate the amount of NPs taken up by 4T1 cell lines using flow cytometry, with a statistical significance of p < 0.01 (B).

Cellular internalization study of free Dox and Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) in MDA-MB-231 cells, and the results were observed after 1 and 4 h of incubation (A).The histogram and a bar graph were used to demonstrate the amount of NPs taken up by MDA-MB-231 cell lines using flow cytometry, with a statistical significance of p < 0.01 (B).

Cellular internalization mechanism

To understand the internalization mechanism of the nanobots, various endocytosis inhibitors35 were used such as chlorpromazine (inhibitor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis), Nystatin (inhibitor of caveolae/lipid-mediad endocytosis) and Amiloride (inhibitor of macropinocytosis, and Na+/H+ exchange). Figure 7A and B shows that treatment with these inhibitors effects on the fluorescence intensity compared to the no inhibitor treatment for both MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cell lines. Notably, the use of chlorpromazine exhibited the lowest fluorescence, while treatment with amiloride displayed the highest fluorescence in both the cell lines. This evidence indicated that the Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) nanobots was internalized into the cells through the endocytosis with the clathrin-mediated mechanism being the most prominent and the caveolae-mediated endocytosis mechanism being the least significant.

Internalization mechanism of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A). Cellular uptake of the Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) was checked following treatment with endocytosis inhibitors. After 4 h treatment with Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A), MDA-MB-231 cells and 4T1 cells were observed for fluorescence using confocal microscopy (A) and (B). Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A)with Chlorpromazine, Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) with Nystatin, and Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) with Amiloride.

Reactive oxygen species generation

Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) is used as a fluorescent probe for the detection of intracellular reactive oxygen species36 (ROS). DCFH-DA lacks inherent fluorescence and can readily traverse cell membranes. Upon entering the cell, intracellular esterases hydrolyze DCFH-DA to generate Dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCFH). Subsequently, ROS oxidize DCFH to yield the fluorescent compound 2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescein (DCF). The fluorescence intensity of DCF is used to quantify the level of ROS. Figure 8A and C illustrate the fluorescence observed via confocal microscope imaging, while Fig. 8B and D depict flow cytometry analysis of cells treated with free drug and Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) nanobots in MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cell lines. The spectral shift and Mean Fluorescent Intensity from Fig. 8B and D demonstrated a significant increase in fluorescence intensity for Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) in both cell lines (MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cell lines), indicating a substantial generation of ROS within the treated cells. The generation of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (·OH) by Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) is attributed to the fenton reaction occurring between Fe3+ and H2O2. These hydroxyl radicals exhibit potent oxidative properties, capable of causing damage to DNA and other biomolecules, ultimately leading to the destruction of cancer cells37.

Cell cycle analysis

The cell cycle analysis on MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cell lines (Fig. 9A and B) indicates maximum arrest in the G2-M phase for the Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) nanobots, aligning with the mechanism of Dox, which involves mitotic apoptosis through the disruption of cell division stages by inhibiting the ability of microtubules to rearrange38. Thus, the cell cycle analysis study guides about the mechanism of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) nanobots for cytotoxicity by demonstrating cell division inhibition in the early anaphasic stage (M-phase).

Methods

Reagents

Ferric chloride tetrahydrate, ferrous chloride hexahydrate, glutathione (GSH) and N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC.HCl) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX) was received as a gift from Naprod Life Sciences, India. Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), Penicillin-streptomycin antibiotic, MTT, and trypsin-EDTA were purchased from Himedia, Mumbai.

Synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4)

Ferric chloride tetrahydrate and ferrous chloride hexahydrate were dissolved in distilled water at a 2:1 ratio. The co-precipitation of ferric and ferrous ions was achieved by adding an aqueous ammonia solution (pH 9). The mixture was then heated to 80 °C for 30 min. The precipitated iron oxide nanoparticles were separated magnetically and washed with distilled water until the solution reached a pH of 7. Subsequently, the iron oxide nanoparticles were isolated and dried at 60–70°C39.

Synthesis of glutathione (GSH) functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe-GSH)

In a solution consisting of 150 µl of distilled water and 50 µl of methanol, 50 mg of Fe3O4nanoparticles were added and sonicated for 15 min. A separate solution containing 5 mg of GSH in 50 µl of distilled water was prepared. Both solutions were mixed and sonicated intermittently for a period of 2 h. The GSH-functionalized nanoparticles were separated magnetically and washed with distilled water40.

Conjugation of plasma proteins with Fe3O4-GSH nanoparticles (Fe-GSH-Protein)

10 mg of Fe-GSH nanoparticles were mixed with a solution consisting of 250 µl of NHS (1 mg/mL) and 250 µl of EDC (1 mg/mL), and vortexed for 30 min. Subsequently, this mixture was combined with 1 mL of whole plasma and vortexed intermittently for a period of 4 h. The protein-conjugated nanoparticles were then magnetically separated and washed with distilled water.

Synthesis of DOX loaded Fe-GSH-Protein nanoparticles (Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox)

10 mg of Fe-GSH-Protein nanoparticles were mixed with a solution containing 250 µl of NHS (1 mg/mL) and 250 µl of EDC (1 mg/mL) and vortexed for 30 min. Then, 1 mL of DOX solution (10 mg/mL) was added to it and vortexed intermittently for a period of 4 h. The DOX-conjugated nanoparticles were then magnetically separated and washed with distilled water 2–3 times to remove the unconjugated doxorubicin (Fe-GSH-Protein-DOX (C)). Similarly, the magnetically separated nanoparticles were dried without washing to obtain doxorubicin-conjugated and adsorbed nanoparticles (Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A)).

Characterization

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis was conducted using the FEI Tecnai G2, F30 instrument at an accelerating potential of 300 kV. Samples of the Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox suspension in deionized water were prepared, and droplets were deposited onto a Formvar-coated copper grid. Subsequently, the water evaporated at room temperature before imaging. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectral studies were performed using a Shimadzu (8400 S) FTIR spectrometer, covering the range from 4000 to 400 cm − 1. UV-Vis absorption spectra were recorded using a Shimadzu UV-1900 UV spectrophotometer.

Study of velocity and motion behaviour of nanobots

The autonomous propulsion of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanoparticles was evaluated in in PBS and plasma containing 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8% H2O2. The motion of nanoparticles was recorded using a camera with high magnification capacity. All recorded videos were converted into AVI format using Format Factory, and the best video clips were selected using VirtualDub 1.10.4 (http://www.virtualdub.org/). The motion and speed of nanoparticles were tracked and measured using the MTrackJ plugin from ImageJ 1.8.0_112 (https://imagej.net/MTrackJ).

Drug release profiles of the nanobots

The drug release profile of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanoparticles was evaluated in phosphate buffers of pH 7.4 and pH 5. 5 mg of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanoparticles were suspended in 10 mL of buffer solution and continuously stirred at room temperature. 1mL aliquot was withdrawn after each time interval, centrifuged, and subsequently analyzed using a UV-Visible spectrophotometer at a λmax of 484 nm. The same aliquot was then transferred back into dissolution media. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Cell culture

The human epithelial breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231) and mouse epithelial breast cancer cell line (4T1) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA). A complete DMEM medium was utilized to sustain the cell lines, consisting of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin antibiotic solution. The cell cultures were diligently maintained in an incubator set at 37 °C with a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxic potential of the developed formulation was evaluated by MTT assay. The MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cells at a density of 10 × 103 in DMEM complete growth media were added to each well of 96 well plates and kept in incubation for 24 h 41. After incubation, the cells were exposed to serial dilutions of Fe, Fe-GSH, Fe-GSH-Protein, Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A), Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (C), and Dox solutions (concentrations ranging from 3.125 to 200 µg/mL) and further incubated for 24 h. Then, the culture medium was removed and 50 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h to form formazan crystals by the viable cells. The supernatant was carefully removed, and the formazan crystals were dissolved with 150 µL of DMSO. After another 30 min of incubation, the absorbance of the solution was recorded using a microplate reader (Spectramax™, Molecular Devices, USA) at 590 nm (reference wavelength 620 nm) at 590–620 nm. The cells in the control well were not treated with the formulation. Triplicates of each sample were analyzed and expressed as mean ± SD. The equation used to calculate cell viability is given below:

Cell viability = (A samples – A blank)/(A control –A blank) × 100%.

A sample is an average absorbance in wells containing cells treated with a defined concentration of the sample; A blank is an absorbance of blank (DMSO), and A control is the absorbance of the untreated cells used as a negative control.

Cellular uptake in monolayer

To visualize the internalization of formulation into the monolayer of cells, a Confocal microscopic study was used. In brief, the MDA-MB-231 and 4T1cells were seeded onto a coverslip placed in a 12-well plate at a density of 50,000 cells/well and kept in incubation overnight to confluence42. After reaching 80% confluence, the cells were treated with 100 µL of Dox, Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) at Dox concentration 6 µg/mL and kept incubating for 1 and 4 h. After incubation, media was removed, and the cells were washed twice with PBS (300 µL), and 100 µL DAPI (6 µg/mL) was added and kept aside for 5 min, followed by fixation of cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. The coverslips were placed on glass slides with the aid of fluoromount-G and observed under a confocal microscope.

Flow cytometry

The study’s objective was to assess Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) cellular uptake using flow cytometry. For this, 0.2 × 106 cells/well were plated in a 12-well plate and incubated overnight. Following incubation for 1 h and 4 h, the cells were carefully washed with PBS, detached using trypsin, and then centrifuged. Subsequently, the cells were resuspended in PBS. To measure the internalization of the formulation within the cells, a flow cytometer (FACS ARIA III, BD Life Sciences) was employed. Each group underwent analysis of 10,000 cells to obtain statistically significant results.

Cellular internalization mechanism

Confocal microscopy investigated the cellular internalization mechanism (endocytosis mechanism)43. The experimental procedure involved seeding both cell lines into 12-well tissue culture plates at a density of 50,000 cells per well. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were exposed to specific inhibitors: 20 µg/mL of chlorpromazine (clathrin-mediated endocytosis inhibitor), nystatin (caveolae-mediated endocytosis inhibitor), and Amiloride (macropinocytosis-mediated endocytosis inhibitor) for 1 h. Following the inhibitor treatment, the media was removed, and the cells were treated with the Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A). The uptake of the nanobots was then observed for duration of 4 h. Once the required incubation time with the treatment was completed, the cells underwent processing according to the procedure mentioned above and were subsequently examined under the confocal microscope.

Reactive oxygen species

The two cell lines were seeded and allowed to grow overnight in 12-well culture plates at a cell density of 5 × 104cells per well44. Subsequently, the cells were treated with Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) (with a Dox concentration of 6 µg/mL) for 24 h. After the treatment period, the cells were fixed using the previously described method, and DCHFDA (at a concentration of 5 µM with excitation/emission wavelengths of 504/529 nm) was introduced. Following a 20-minute incubation with DCHFDA, the cells were washed, and confocal microscope images were taken for further analysis.

Cell cycle analysis

One million cells were utilized for cell cycle analysis after 24-hour exposure to free Dox and Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A). The cells were collected and fixed by incubating in 70% cold ethanol for 30 min at 4°C45. The cells were washed with PBS and treated with 50 µL of RNase to ensure specific DNA staining. Subsequently, 200 µL of PI was added to the samples, and flow cytometry was employed to measure the fluorescence intensity. Forward and side scatters were measured to locate the single cells with an emission wavelength of 610 nm. The data for one million (n = 1 × 106) cells were analyzed using Phoenix Flow Systems’ Multi Cycle AV for Windows software.

Conclusion

We have designed and developed Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox as self-propelling, magnetic nanobots with surface-functionalized plasma proteins to establish a dynamic and targeted drug delivery platform. The magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles were conjugated to plasma proteins using a GSH linker, resulting in a biocompatible and chemically functionalized surface that offers a larger chemical space for drug conjugation/loading. Herein, Fe3O4 nanoparticles play multiple roles, providing magnetic navigation, autonomous propulsion and surface for chemical conjugation. Moreover, Fe3O4 reacts with the elevated levels of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to produce highly reactive hydroxyl radicals that have the potential to damage DNA and other biomacromolecules within cancer cells. This nanosystem demonstrated a controlled and pH-responsive drug release profile, where maximum drug release occurs at acidic pH (lysosomal pH) to reduces the burst release of cytotoxic drugs in the systemic circulation. The Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots exhibited notably faster propulsion in plasma compared to PBS, attributed to the interaction between hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and adsorbed catalase enzymes. Additionally, the propulsive force exerted by the nanobots was significantly higher in serum (9.02, 24.55, and 31.9 nN) compared to PBS (5.72, 12.35, and 19.46 nN for 0.1%, 2%, and 4% H2O2 respectively). Consequently, these enhanced speed and force capabilities of the nanobots confer a significant advantage for enhanced propulsion and deep tumor penetration. The confocal imaging and flow cytometry data from the cellular uptake study clearly demonstrated faster internalization and higher nuclear accumulation of the drug when using Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) nanobots, highlighting their potential for superior cellular uptake compared to free doxorubicin. This distinct uptake profile may be attributed to the enhanced targeting, cell penetration, and pH-responsive drug release kinetics of the nanobots. The experiments with endocytosis inhibitors helped to elucidate cellular internalization mechanism of nanobots, wherein low fluroscence intensity with the use of chlorpromazine indicated clarithrin-mediated endocytosis. The superior internalization kinetics of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) and (C) compared to free DOX resulted in lower IC50 values. Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) demonstrated IC50 values of 6.30 µg/mL and 4.2 µg/mL after 24 and 48 h of treatment on MDA-MB-231 cell lines, respectively. Similarly, for 4T1 cell lines, Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) displayed IC50 values of 7.63 µg/mL and 5.20 µg/mL after 24 and 48 h of treatment, respectively. The DCFH-DA fluorescent probe-based study for the analysis of ROS generation demonstrated a significant increase in fluorescence and thus ROS with Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) in both cell lines (MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cell lines). ROS causes damage to DNA and other biomolecules, ultimately leading to the destruction of cancer cells. Additionally, cell cycle analysis revealed that Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox (A) nanobots induce maximum cell arrest in the G2-M phase, inhibiting cell division in the early anaphase stage (M-Phase), which abiding with the mechanism of action of doxorubicin. Overall, Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots, proposed as a biocompatible system, demonstrate a self-propelling mechanism powered by oxygen bubbles, aiding in deep tumor penetration and enhancing drug delivery precision. Furthermore, the nanobots exhibit pH-responsive controlled drug release and higher nuclear accumulation of doxorubicin in TNBC cells. This innovation holds the potential to significantly improve TNBC treatment by providing safer, targeted chemotherapy and addressing current therapeutic limitations. However, In-vivo studies are required to confirm the efficacy and safety of Fe-GSH-Protein-Dox nanobots in animal models. Additionally, the heterogeneity of TNBC presents challenges in generalizing the results across all subtypes.

Data availability

The data generated during this study are included in the published article and the Supplementary Information.

References

Patra, Debabrata, Samudra Sengupta, Wentao Duan, Hua Zhang, Ryan Pavlick, and Ayusman Sen. “Intelligent, self-powered, drug delivery systems.” Nanoscale 5, no. 4 (2013): 1273–1283.

Gao, Wei, and Joseph Wang. “Synthetic micro/nanomotors in drug delivery.” Nanoscale 6, no. 18 (2014): 10486–10494.

Zhang, Shuhao, Chaoran Zhu, Wanting Huang, Hua Liu, Mingzhu Yang, Xuejiao Zeng, Zhenzhong Zhang et al. “Recent progress of micro/nanomotors to overcome physiological barriers in the gastrointestinal tract.” Journal of Controlled Release 360 (2023): 514–527.

Peng, Fei, Yingfeng Tu, and Daniela A. Wilson. “Micro/nanomotors towards in vivo application: cell, tissue and biofluid.” Chemical Society Reviews 46, no. 17 (2017): 5289–5310.

Baylis, James R., Ju Hun Yeon, Max H. Thomson, Amir Kazerooni, Xu Wang, Alex E. St. John, Esther B. Lim et al. “Self-propelled particles that transport cargo through flowing blood and halt hemorrhage.” Science advances 1, no. 9 (2015): e1500379.

Andhari, Saloni S., Ravindra D. Wavhale, Kshama D. Dhobale, Bhausaheb V. Tawade, Govind P. Chate, Yuvraj N. Patil, Jayant J. Khandare, and Shashwat S. Banerjee. “Self-propelling targeted magneto-nanobots for deep tumor penetration and pH-responsive intracellular drug delivery.” Scientific reports 10, no. 1 (2020): 4703.

Villa, Katherine, Ludmila Krejčová, Filip Novotný, Zbynek Heger, Zdeněk Sofer, and Martin Pumera. “Cooperative multifunctional self-propelled paramagnetic microrobots with chemical handles for cell manipulation and drug delivery.” Advanced Functional Materials 28, no. 43 (2018): 1804343.

Wu, Zhiguang, Yingjie Wu, Wenping He, Xiankun Lin, Jianmin Sun, and Qiang He. “Self-propelled polymer‐based multilayer nanorockets for transportation and drug release.” Angewandte Chemie International Edition 52, no. 27 (2013): 7000–7003.

Han, Koohee, C. Wyatt Shields IV, and Orlin D. Velev. “Engineering of self-propelling microbots and microdevices powered by magnetic and electric fields.” Advanced Functional Materials 28, no. 25 (2018): 1705953.

Xu, Tailin, Li-Ping Xu, and Xueji Zhang. “Ultrasound propulsion of micro-/nanomotors.” Applied Materials Today 9 (2017): 493–503.

Tu, Yingfeng, Fei Peng, Xiaofeng Sui, Yongjun Men, Paul B. White, Jan CM van Hest, and Daniela A. Wilson. “Self-propelled supramolecular nanomotors with temperature-responsive speed regulation.” Nature chemistry 9, no. 5 (2017): 480–486.

Tang, Minglu, Jiatong Ni, Zhengya Yue, Tiedong Sun, Chunxia Chen, Xing Ma, and Lei Wang. “Polyoxometalate-Nanozyme‐Integrated Nanomotors (POMotors) for Self‐Propulsion‐Promoted Synergistic Photothermal‐Catalytic Tumor Therapy.” Angewandte Chemie 136, no. 6 (2024): e202315031.

Al-Bataineh, Osama, Jürgen Jenne, and Peter Huber. “Clinical and future applications of high intensity focused ultrasound in cancer.” Cancer treatment reviews 38, no. 5 (2012): 346–353.

Peng, Xia, Mario Urso, Jan Balvan, Michal Masarik, and Martin Pumera. “Self-Propelled Magnetic Dendrite‐Shaped Microrobots for Photodynamic Prostate Cancer Therapy.” AngewandteChemie International Edition 61, no. 48 (2022): e202213505.

Khan, Mohd Imran, Akbar Mohammad, Govil Patil, S. A. H. Naqvi, L. K. S. Chauhan, and Iqbal Ahmad. “Induction of ROS, mitochondrial damage and autophagy in lung epithelial cancer cells by iron oxide nanoparticles.” Biomaterials 33, no. 5 (2012): 1477–1488.

Bianchini, Giampaolo, Justin M. Balko, Ingrid A. Mayer, Melinda E. Sanders, and Luca Gianni. “Triple-negative breast cancer: challenges and opportunities of a heterogeneous disease.” Nature reviews Clinical oncology 13, no. 11 (2016): 674–690.

Ensenyat-Mendez, Miquel, Pere Llinàs-Arias, Javier IJ Orozco, Sandra Íñiguez-Muñoz, Matthew P. Salomon, Borja Sesé, Maggie L. DiNome, and Diego M. Marzese. “Current triple-negative breast cancer subtypes: dissecting the most aggressive form of breast cancer.” Frontiers in oncology 11 (2021): 681476.

Dent, Rebecca, Maureen Trudeau, Kathleen I. Pritchard, Wedad M. Hanna, Harriet K. Kahn, Carol A. Sawka, Lavina A. Lickley, Ellen Rawlinson, Ping Sun, and Steven A. Narod. “Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence.” Clinical cancer research 13, no. 15 (2007): 4429–4434.

Lv, Yan, Xiao Ma, Yuxin Du, and Jifeng Feng. “Understanding patterns of brain metastasis in triple-negative breast cancer and exploring potential therapeutic targets.” OncoTargets and therapy (2021): 589–607.

Lin, Nancy U., Ann Vanderplas, Melissa E. Hughes, Richard L. Theriault, Stephen B. Edge, Yu-Ning Wong, Douglas W. Blayney, Joyce C. Niland, Eric P. Winer, and Jane C. Weeks. “Clinicopathologic features, patterns of recurrence, and survival among women with triple‐negative breast cancer in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.” Cancer 118, no. 22 (2012): 5463–5472.

Marra, Antonio, Dario Trapani, Giulia Viale, Carmen Criscitiello, and Giuseppe Curigliano. “Practical classification of triple-negative breast cancer: intratumoral heterogeneity, mechanisms of drug resistance, and novel therapies.” NPJ breast cancer 6, no. 1 (2020): 54.

Wavhale, Ravindra D., Kshama D. Dhobale, Shraddha Patil, Govind P. Chate, Bhausaheb V. Tawade, Yuvraj N. Patil, and Shashwat S. Banerjee. “Self-Propelled Catalytically Powered Dual‐Engine Magnetic Nanobots for Rapid and Highly Efficient Capture of Circulating Fetal Trophoblasts.” Advanced Materials Interfaces 9, no. 22 (2022): 2200522.

Szatrowski, Ted P., and Carl F. Nathan. “Production of large amounts of hydrogen peroxide by human tumor cells.” Cancer research 51, no. 3 (1991): 794–798.

Zheng, Jingtao, Yanyan Pan, Yubin Chen, Junyan Li, and Weishuo Li. “Hypoxic tumor therapy based on free radicals.” Materials Chemistry Frontiers (2023).

Mollazadeh, Shirin, Saeed Babaei, Mehdi Ostadhassan, and RezvanYazdian-Robati. “Concentration-dependent assembly of Bovine serum albumin molecules in the doxorubicin loading process: Molecular dynamics simulation.” Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 640 (2022): 128429.

Kratz, Felix, and Bakheet Elsadek. “Clinical impact of serum proteins on drug delivery.” Journal of Controlled Release 161, no. 2 (2012): 429–445.

Zhang, Xingming, Tuan-Anh Le, Ali Kafash Hoshiar, and Jungwon Yoon. “A soft magnetic core can enhance navigation performance of magnetic nanoparticles in targeted drug delivery.” IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 23, no. 4 (2018): 1573–1584.

Wu, Huanhuan, Keman Cheng, Yuan He, Ziyang Li, Huiling Su, Xiuming Zhang, Yanan Sun, Wei Shi, and Dongtao Ge. “Fe3O4-based multifunctional nanospheres for amplified magnetic targeting photothermal therapy and Fenton reaction.” ACS biomaterials science & engineering 5, no. 2 (2018): 1045–1056.

Liang, Chaolun, Teng Zhai, Wang Wang, Jian Chen, Wenxia Zhao, Xihong Lu, and Yexiang Tong. “Fe 3 O 4/reduced graphene oxide with enhanced electrochemical performance towards lithium storage.” Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2, no. 20 (2014): 7214–7220.

Sun, Conroy, Kim Du, Chen Fang, Narayan Bhattarai, Omid Veiseh, Forrest Kievit, Zachary Stephen et al. “PEG-mediated synthesis of highly dispersive multifunctional superparamagnetic nanoparticles: their physicochemical properties and function in vivo.” ACS nano 4, no. 4 (2010): 2402–2410.

Fytory, Mostafa, Amira Mansour, Waleed MA El Rouby, Ahmed A. Farghali, Xiaorong Zhang, Frank Bier, Mahmoud Abdel-Hafiez, and Ibrahim M. El-Sherbiny. “Core–Shell Nanostructured Drug Delivery Platform Based on Biocompatible Metal–Organic Framework-Ligated Polyethyleneimine for Targeted Hepatocellular Carcinoma Therapy.” ACS omega 8, no. 23 (2023): 20779–20791.

She, Wenchuan, Ning Li, Kui Luo, Chunhua Guo, Gang Wang, Yanyan Geng, and Zhongwei Gu. “Dendronized heparin − doxorubicin conjugate-based nanoparticle as pH-responsive drug delivery system for cancer therapy.” Biomaterials 34, no. 9 (2013): 2252–2264.

Arroyo-Crespo, Juan J., Ana Armiñán, David Charbonnier, Coralie Deladriere, Martina Palomino‐Schätzlein, Rubén Lamas‐Domingo, Jeronimo Forteza, Antonio Pineda‐Lucena, and Maria J. Vicent. “Characterization of triple‐negative breast cancer preclinical models provides functional evidence of metastatic progression.” International journal of cancer 145, no. 8 (2019): 2267–2281.

Goren, Dorit, Aviva T. Horowitz, Dina Tzemach, Mark Tarshish, Samuel Zalipsky, and Alberto Gabizon. “Nuclear delivery of doxorubicin via folate-targeted liposomes with bypass of multidrug-resistance efflux pump.” Clinical Cancer Research 6, no. 5 (2000): 1949–1957.

Francia, Valentina, Catharina Reker-Smit, Guido Boel, and Anna Salvati. “Limits and challenges in using transport inhibitors to characterize how nano-sized drug carriers enter cells.” Nanomedicine 14, no. 12 (2019): 1533–1549.

Gomes, Ana, Eduarda Fernandes, and José LFC Lima. “Fluorescence probes used for detection of reactive oxygen species.” Journal of biochemical and biophysical methods 65, no. 2–3 (2005): 45–80.

Ranji-Burachaloo, Hadi, Paul A. Gurr, Dave E. Dunstan, and Greg G. Qiao. “Cancer treatment through nanoparticle-facilitated fenton reaction.” ACS nano 12, no. 12 (2018): 11819–11837.

Tacar, Oktay, Pornsak Sriamornsak, and Crispin R. Dass. “Doxorubicin: an update on anticancer molecular action, toxicity and novel drug delivery systems.” Journal of pharmacy and pharmacology 65, no. 2 (2013): 157–170.

Banerjee, S. S. & Chen, D.-H. Magnetic Nanoparticles Grafed with Cyclodextrin for Hydrophobic Drug Delivery. Chem. Mater. 19, 6345–6349 (2007).

Polshettiwar, V., Baruwati, B. & Varma, R. S. Magnetic nanoparticle-supported glutathione: A conceptually sustainable organocatalyst. Chem. Commun. 14, 1837–1839 (2009).

Vysyaraju NR, Paul M, Ch S, Ghosh B, Biswas S. Olaparib@ human serum albumin nanoparticles as sustained drug-releasing tumour-targeting nanomedicine to inhibit growth and metastasis in the mouse model of triple-negative breast cancer. Journal of Drug Targeting. 2022 Nov 21;30(10):1088 − 105.

Kumari P, Paul M, Bhatt H, Rompicharla SV, Sarkar D, Ghosh B, Biswas S. Chlorin e6 conjugated methoxy-poly (ethylene glycol)-poly (d, l-lactide) glutathione sensitive micelles for photodynamic therapy. Pharmaceutical Research. 2020 Feb;37:1–7.

Itoo AM, Paul M, Ghosh B, Biswas S. Oxaliplatin delivery via chitosan/vitamin E conjugate micelles for improved efficacy and MDR-reversal in breast cancer. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2022 Apr 15;282:119108.

Itoo AM, Paul M, Ghosh B, Biswas S. Polymeric graphene oxide nanoparticles loaded with doxorubicin for combined photothermal and chemotherapy in triple negative breast cancer. Biomaterials Advances. 2023 Jul 5:213550.

Kumbham S, Paul M, Itoo A, Ghosh B, Biswas S. Oleanolic acid-conjugated human serum albumin nanoparticles encapsulating doxorubicin as synergistic combination chemotherapy in oropharyngeal carcinoma and melanoma. International journal of pharmaceutics. 2022 Feb 25;614:121479.

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge the DST-FIST research facility, supported by the Government of India, at Dr. D. Y. Patil Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, Pimpri, Pune.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R. W. conceived the idea. R. W and S. B. designed the experiments. R. W., S. C., and S. B. analysed the experimental and calculated data. N. N., M. P., R. W., and S. B. contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. N. N. prepared the nanobots and conducted the motion experiments. M. P. carried out the In-vitro cellular studies. R. W. and S. B. directed the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 2

Supplementary Material 3

Supplementary Material 4

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naikwadi, N., Paul, M., Biswas, S. et al. Self-propelling, protein-bound magnetic nanobots for efficient in vitro drug delivery in triple negative breast cancer cells. Sci Rep 14, 31547 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83393-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83393-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Dual-source powered sea urchin-like nanomotors for intravesical photothermal therapy of bladder cancer

Journal of Nanobiotechnology (2025)