Abstract

Alcohol use attenuates successful smoking cessation. We examined the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a brief alcohol intervention in smokers. In this two-arm, assessor-blinded randomized controlled trial, we randomized 100 daily smokers (82.0% male, mean age = 43.7 years) with past-year alcohol use in smoking cessation clinics. Both intervention (n = 51) and control (n = 49) groups received conventional smoking cessation treatment, the intervention group additionally received a brief alcohol intervention. Primary outcome was biochemically validated tobacco abstinence at 2 months. Secondary outcomes included Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) scores, self-reported past 7-day alcohol consumption in alcohol units, feasibility, and acceptability scores at 2 months. By intention-to-treat, the intervention group showed higher validated abstinence (11.8% vs. 10.2%, Risk Ratio = 1.15, 95%CI = 0.38–3.53), lower AUDIT score (5.3 vs. 6.5), and lower alcohol consumption (5.6 vs. 7.1) than the control group, but the differences were not significant. Overall, the feasibility was high (4.2/5.0), and the acceptability was modest (5.0/7.0). In all participants, reduction in smoking relapse risk due to alcohol use from baseline to 2-month follow-up was associated with higher biochemically validated abstinence (Adjusted odds ratio: 1.55, 95% CI = 1.05–2.28). Our brief alcohol intervention is feasible, acceptable, and potentially efficacious to promote tobacco abstinence and alcohol reduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alcohol use in smokers is common worldwide. Previous population-based studies from the United States1, Germany2, South Korea3, Mongolia4, and Thailand5 showed that the prevalence of current daily/monthly drinking in current smokers ranged from 6.5 to 22.4%. Alcohol use attenuates smoking cessation (SC) because alcohol (1) increases nicotine rewarding effect, as alcohol enhances satisfaction and pleasantness from nicotine; (2) increases nicotine reinforcement, and hence greater subsequent cigarette consumption for intaking more nicotine; and (3) triggers nicotine craving and increases the risks of smoking lapse and relapse6,7. Urges to smoke could also be triggered by the smell of alcohol8,9 and alcohol-related images10. A recent systematic review showed that smokers or quitters with habitual alcohol use were more likely to experience smoking relapse after tobacco abstinence7.

Several international clinical guidelines for SC recommended clinicians to help smokers reduce or abstain from alcohol use during SC11,12,13. Our searches on PudMed up to Sep 24, 2023, using keywords such as “alcohol”, “drinking”, “tobacco”, “smokers”, “smoking cessation”, “intervention”, and “treatment” found 3 pilot randomized controlled trials (RCTs)14,15,16 and 3 RCTs17,18,19 that examined the effectiveness of non-pharmacological alcohol interventions integrated into SC treatments. These trials showed inconsistent results on the intervention effectiveness. Particularly, one pilot RCT14 and one RCT18 showed the intervention increased tobacco abstinence and reduced alcohol use. One pilot RCT16 and one RCT19 showed improvement on tobacco abstinence only, whereas another RCT17 showed improvement on alcohol reduction only. Another pilot RCT15 showed the intervention did not significantly increase tobacco abstinence nor reduce alcohol use. Besides, all these trials targeted smokers with unhealthy drinking habit including binge drinking14,17, heavy drinking15,16,18 and hazardous drinking19. No previous RCTs targeted smokers with social or moderate alcohol consumption despite their lower tobacco abstinence rate observed in some studies20,21.

In Hong Kong, the overall smoking prevalence was 9.1% in 202322. Notably, about one fourth of adult population reported alcohol use in past year23, whereas approximately 33.6% of current smokers reported alcohol use at least monthly24. A retrospective cohort study in Hong Kong showed that higher Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) scores were associated with lower tobacco abstinence at both week 26 and week 5225. The 10-item AUDIT has been adopted in primary care setting for identifying risky alcohol users and tailoring brief advice on alcohol use26. However, our formative qualitative study with SC service providers in Hong Kong revealed that there is no standard guidelines or intervention protocols for delivering alcohol intervention for smokers during SC27. An alcohol control intervention which fits for all alcohol drinkers is potentially beneficial to many more smokers who have the risk to relapse due to alcohol use. The present RCT aimed to examine the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a brief alcohol intervention during conventional SC treatments.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study was a 2-arm, parallel, pilot RCT conducted in Tung Wah Group of Hospitals Integrated Centre on Smoking Cessation (ICSC) in Hong Kong SAR. ICSC is a government-funded SC service28 which offers free SC treatments including multiple sessions counselling, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), and varenicline. This trial was approved by Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (UW 21–347) and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05430529, first trial registration date 24/06/2022). Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline and the extension to randomized pilot and feasibility trials were followed29.

Participants

All ICSC counsellors as interventionists were proficient in various SC techniques and approaches, including (but not limited to) motivational interviewing techniques, the “5 A’s” (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange), and the “5 R’s” (Relevance, Risks, Rewards, Roadblocks, and Repetition)”. On June 6, 2022, the research team delivered a 2-hour training to 13 counsellors of the ICSC on recruitment procedures and intervention delivery, covering (1) the relationship between tobacco and alcohol use, (2) administration and scoring of Screening Tool for Alcohol Control in Smokers (STACS), (3) brief counseling for alcohol control, (4) harms of alcohol drinking, (5) calculation on alcohol units, and (6) common alcoholic beverages and drinking culture in Hong Kong. From June 17 to September 15, 2022, the trained counsellors conducted the recruitment in all 5 clinics under the ICSC. During the first SC consultation via face-to-face or telephone, the trained counsellors screened smokers’ eligibility. Eligible smokers consented and completed a baseline questionnaire on their smoking and drinking patterns. Participants were randomized to either the intervention group or the control group, and were reimbursed a HK$20 (~ US$2.6) voucher for enrolment.

Inclusion criteria were (1) aged 18 years or above, (2) able to communicate in Cantonese/Mandarin and read Chinese, (3) self-reported daily tobacco use in the past month, (4) past-year alcohol use assessed by AUDIT, (5) STACS scored equal to 1 or above indicating potential risks of smoking lapse and relapse due to alcohol use, and (6) currently using the ICSC SC service. The STACS was a psychometric instrument developed by our team to assess the risks of smoking lapse and relapse due to alcohol use. It contains 5 binary (no = 0, yes = 1) items assessing whether participants (1) had smoking relapse due to alcohol use in previous quit attempts, (2) ever felt the urge to smoke while drinking alcohol or afterwards, (3) ever smoked while drinking alcohol, (4) ever increased tobacco consumption on days of drinking alcohol, compared to days of not drinking alcohol, and (5) perceived alcohol use would reduce their motivation to quit smoking. The total score of STACS ranged from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher risks of smoking relapse due to alcohol use. Exclusion criteria were (1) unstable physical or psychological conditions advised by doctors or counsellors, (2) illicit drug (e.g. heroin) use, or (3) being pregnant.

Randomization, allocation concealment and blinding

Participants were individually randomized (1:1) to the intervention or control group by the randomizer function of an online survey tool “Qualtrics” set up by the investigators who were not involved in the participant recruitment. The “Evenly Present Elements” function was used to recruit similar number of participants in both groups. For allocation concealment, the counsellors applied the randomizer after the participant provided the study consent. The counsellors were not able to modify randomisation results. Both counsellors and participants were not blinded to the intervention. Outcome assessors and data analysts who were not involved in the recruitment and intervention delivery were blinded to the group allocation.

Interventions

Brief alcohol intervention

We conducted a formative qualitative study with 14 health care professionals and 20 smokers to explore their perceptions, attitudes, and preferences regarding alcohol control during SC treatment27. Results showed that health care professionals lacked standardized guidelines and intervention protocols to help smokers reduce alcohol consumption and the smoking relapse risk due to alcohol use. Additionally, smokers did not prioritize alcohol control as they perceived their drinking level was low. Therefore, we developed a brief alcohol intervention for smokers based on these findings. The content of the intervention was based on 2 principles: (1) brief counselling and personalized advice that were embedded in the SC service and delivered by the same counsellors who also delivered the SC treatments; and (2) emphasized on self-determination30, meaning that the counsellors and the participants agree on a treatment goal of alcohol control. The brief alcohol intervention comprised (1) a 3-minute short video or health advice about alcohol control specifically for smokers, (2) a 5-minute counselling on goal setting for alcohol control embedded in the SC counselling session (which usually took about 30 min), (3) an education leaflet, (4) 4-week personalized WhatsApp messages (3 messages per week), and (5) AUDIT-based brief advice which was developed by World Health Organisation (WHO)31 and has been adopted in primary care setting in Hong Kong26. For example, if participant’s AUDIT score range between 1 and 7 (lower-risk drinking), counsellors would advise participant to (1) drink less or totally abstain from alcohol for preventing cancer and diseases, and (2) try to limit the maximum alcohol consumption to 2 alcohol units (for men) or 1 unit (for women) a day. The video (Appendix A) and the leaflet (Appendix B) covered knowledge on (1) harms of alcohol, (2) the relationship between alcohol use and SC, (3) alcohol control skills (e.g. setting a maximum alcohol consumption in each drinking episode, substitute with non-alcoholic beverages when attending drinking occasions such as in bar and nightclub), and (4) clarification of misconceptions of alcohol.

The counsellors first played the short video to participants who enrolled face-to-face during the first SC treatment after randomisation. For the participants enrolled by phone, counsellors delivered a health advice which included the same contents as the short video, and they would send the short video clip via WhatsApp. During the brief counselling, participants were invited to describe their drinking patterns and were encouraged to pursue one of the following alcohol control goals (1) abstain from alcohol, (2) abstain from alcohol for 2 weeks, (3) reduce alcohol consumption, or (4) no change. Based on participants’ choices, the counsellors delivered personalized advice. For example, for participants who chose to abstain from alcohol or abstain for 2 weeks, they were encouraged to avoid purchasing or storing any alcoholic beverages at home; for participants who chose to reduce alcohol consumption, they were encouraged to set up a maximum alcohol consumption target and self-monitor in each drinking episode. For participants who chose no change, counsellors reminded them that alcohol use may lead to poorer SC outcomes. Furthermore, counsellors invited participants to receive the personalized WhatsApp messages (3 messages per week, 4 weeks in total), delivered the educational leaflet and the AUDIT-based brief advice. The content of the WhatsApp messages was similar to the personalized advice in the brief counselling, which was based on participants’ alcohol control goals and covered more skills in avoiding or reusing drinking, reminders on high-risk social occasions, reviewing the past-week alcohol consumption, and clarification on misconceptions of alcohol.

Control

The control group received a general advice on limiting their daily alcohol consumption to 2 alcohol units for males and 1 alcohol unit for females per the local guideline for the general adult population26 during the conventional SC treatment.

Measures

Participants’ data were collected by a self-administered survey at baseline, and telephone survey at 2 months after randomization. The baseline survey covered sociodemographic characteristics, intention to quit smoking, nicotine dependence measured by the Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI)32, and alcohol dependence measured by AUDIT31. HSI comprises 2 items: (1) time to smoke the first cigarette after waking and (2) daily cigarette consumption. The total score of HSI is the sum of these 2 items, ranging from 0 to 6, with higher score indicating higher level of nicotine dependence. Participants were given HK$50 (~ US$6.4) for the completion of the 2-month follow-up. Primary outcome was biochemically validated tobacco abstinence at 2-month follow-up, defined by an exhaled carbon monoxide level of 3 parts per million or below, confirmed by Smokerlyzer33. Participants who reported tobacco abstinence in the past 7-day were invited to participate in the test.

Secondary outcomes included point prevalence of self-reported 7-day tobacco abstinence (PPA), AUDIT score, self-reported past 7-day alcohol consumption in standard alcohol units (1 alcohol unit = 10-gram pure alcohol), the STACS score, and feasibility and acceptability outcomes. Feasibility outcomes included (1) the recruitment rate (number of subjects enrolled and randomized / number of eligible subjects), (2) retention rate (number of subjects completed the follow-up / number of subjects enrolled and randomized). Three additional feasibility outcomes were assessed by counsellors at the end of the baseline counselling session, which include (1) the time required to deliver the brief alcohol intervention, (2) counsellors’ compliance of the intervention, and (3) an 8-item (5 items for participants and 3 items for counsellors) 5-point Likert scale on the feasibility, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). For example, the participants rated “The brief advice on alcohol control suits my needs”. The counsellors rated “The participant is willing to follow my alcohol control advice”. Furthermore, we also assessed the utilization and perceived satisfaction of the WhatsApp messages by an 8-item scale at 2-month follow-up. For example, “Do you think the frequency of the WhatsApp messages was appropriate?”. Acceptability was measured by a 5-item 7-point Likert scale at 2-month follow-up, including 3 items from The Treatment Acceptability/ Adherence Scale (TAAS)34, each on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). For example, participants rated “The brief alcohol intervention provided practical suggestions and advice to help me cope with my alcohol use in daily life”.

Sample size

As this study was a pilot RCT to generate preliminary estimates for the efficacy of alcohol intervention and inform the sample size of a definitive trial, we recruited and randomized 100 participants (1:1) to each trial group.

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted in SPSS version 25.0 and STATA version 15.1. Descriptive statistics were used to describe sample characteristics, tobacco abstinence rate, reduction of alcohol use, smoking and drinking characteristics, feasibility and acceptability. Comparisons of baseline imbalance were not applicable for pilot trials29. Intention-to-treat analysis was used to include all participants who were randomised in the final analysis. Participants who were lost or refused the follow-up were assumed to have no changes in daily cigarette consumption, alcohol consumption, AUDIT and STACS scores. Log-binominal regression was used to generate risk ratios and estimate the intervention effect on biochemically validated abstinence. Linear regression was used to analyse the intervention effect with standardised regression coefficients (β) on self-reported 7-day alcohol consumption. Sex, age, and baseline daily cigarette consumption were adjusted in these models. We identified 7 participants reported extremely large quantity of alcohol consumption at 2-month follow-up, so we ran another analysis excluding these participants as a sensitivity analysis. Linear mixed model was used to analyze the main and interaction effect between time and group allocation on AUDIT and STACS with crude regression coefficients (β) and Cohen’s F, with and without adjustments for baseline characteristics (sex, age, baseline daily cigarette consumption). Linear mixed model conducted in a small sample from a pilot study was considered feasible and adequate35. To analyze the association between alcohol consumption and SC outcomes, logistic regression analysis not specified in the protocol was done to examine the association between reduction in AUDIT and STACS from baseline to 2-month follow-up (predictors), and biochemically validated and self-reported 7-day PPA of tobacco (outcomes) with odds ratios (OR) with and without adjustment for sex, age, baseline daily cigarette consumption.

Results

Recruitment and baseline demographic

From June 17 to September 15, 2022, 212 of 418 (50.7%) smokers were approached and screened eligible, 100 out of 212 (47.2%) eligible smokers consented and were randomized into either the intervention group (n = 51) or control group (n = 49) (Fig. 1). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the participants were mostly recruited via phone call (87.0%). Table 1 shows that the intervention group had higher proportion of high category in HSI, but all differences were due to chance. The retention rate at 2-month follow-up was 90.0%.

Efficacy of the intervention

Table 2 shows that, by intention-to-treat, the intervention group showed a slightly higher prevalence of biochemically validated tobacco abstinence rate (primary outcome) (12% versus 10%; RR = 1.15, 95% CI 0.38, 3.53, P = 0.725), and slightly lower self-reported 7-day PPA of tobacco (51.0% vs. 59.2%, RR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.60, 1.23, P = 0.245) than the control group at 2-month follow-up, but the differences were not significant. For the self-reported 7-day alcohol consumption at 2-month follow-up, we identified 7 outliers (ranged from 26.0 units to 213.0 units) as these values were not included in the interquartile range (-14.6–25.3) when compared to all participants. After removing the 7 outliers, the intervention group still showed lower self-reported 7-day alcohol consumption (Mean: 5.6 units vs. 7.1 units) but the difference was not significant (β = 1.49, 95% CI=-0.71, 3.69, P = 0.183). Similar results were observed in the adjusted models.

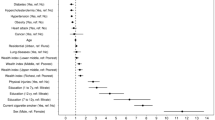

Figure 2 shows the main effect of group allocation and measurement time points and their interaction effect on AUDIT and STACS scores. Both AUDIT (β=-1.08, SE = 0.48, P = 0.024) and STACS (β=-1.25, SE = 0.19, P < 0.001) showed significant decline from baseline to 2-month follow-up. No significant main effect of group allocation on AUDIT (P = 0.718) and STACS (P = 0.609) was found. The interaction effect between time and group allocation on AUDIT scores was moderate but not significant (β=-1.76, SE = 0.94, P = 0.062, f2 = 0.03), and no significant interaction was found on STACS scores, β=-0.21, SE = 0.39, P = 0.587, f2 = 0.002). Hence, we further compared AUDIT scores at baseline and 2-month follow-up for each trial arms with posteriori paired t-tests. In the intervention group, there was a significant difference between baseline (M = 7.2, SD = 6.8) and 2-month follow-up (M = 5.3, SD = 5.5), t(50) = 2.71, P = 0.009. No significant difference was found in the control group (P = 0.769).

Table 3 shows that in all participants, reduction in AUDIT was not significantly associated with biochemically validated tobacco abstinence (OR = 0.98, 95% CI = 0.84, 1.12, P = 0.646) and self-reported 7-day PPA of tobacco (OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.95, 1.13, P = 0.417) at 2-month follow-up. In contrast, reduction in STACS was significantly associated with both biochemically validated tobacco abstinence (OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.00, 1.98, P = 0.049) and self-reported 7-day PPA of tobacco (OR = 2.46, 95% CI = 1.68, 3.74, P < 0.001) at 2-month follow-up. Similar results were also observed in the adjusted models.

Feasibility and acceptability of the intervention

The recruitment rate was 47.2% (100/212) and the retention rate at 2 months was 90.0% (90/100). The average time for delivering the brief alcohol intervention was 8.4 min (SD = 2.6). Counsellors either played the short video (n = 7, 14%) or delivered the health advice via telephone (n = 44, 86%) to all participants in the intervention group. Counsellors delivered the brief counselling of alcohol control (n = 51, 100%), the education leaflet (n = 51, 100%) and the personalized WhatsApp messages (n = 51, 100%) to all participants in the intervention group. The counsellors delivered the AUDIT-based advice to one third of participants in the intervention group (n = 16, 31%). Supplementary table S1 shows that the overall mean score of feasibility was 4.2 (SD = 0.8) out of 5, ranged from 3.8 to 4.6 in each of the 8 items. The overall mean score of acceptability was 5.0 (SD = 1.7) out of 7, ranged from 4.1 to 6.3 in each of the 5 items.

Supplementary table S2 shows that in the intervention group, 47% (24/51) participants read the messages every time they received them. About 27% (14/51) read all contents in the messages, and 22% (11/51) participants read most content in the messages. Moreover, 57% (29/51) participants agreed that the frequency of the messages was appropriate, 51% (26/51) participants would recommend this brief alcohol intervention to other smokers. The mean score of participants’ perceived usefulness, understanding of harms of alcohol, application of the alcohol control advice in daily life from the WhatsApp messages was 3.3 (SD = 1.1), 3.6 (SD = 1.0), 3.1 (SD = 1.1) out of 5, respectively. The overall satisfaction of receiving WhatsApp messages for alcohol control was 3.4 out of 5 (SD = 0.9).

Discussion

We have reported a pilot RCT of integrating a brief alcohol intervention during conventional SC treatment in smokers. The intervention group showed slightly higher biochemically validated tobacco abstinence, lower AUDIT score and past 7-day alcohol consumption than the control group at 2-month follow-up, but the differences were not significant. Only 8.4 min on average was used for the brief alcohol intervention. Our findings also showed high intervention compliance and high feasibility, but the acceptability was modest. Considering the small sample size and the pilot trial design in this study, the findings were preliminary but promising. Notably, 82% of our participants were males, which was consistent with the general population in Hong Kong, where males comprise 85.9% of daily cigarette smokers22. Such findings enhance the generalizability of our results.

We unexpectedly found the majority of our participants (92%) had lower-risk or increasing risk of alcohol dependence in AUDIT. While alcohol use attenuates SC, previous similar trials only focused smokers with heavy alcohol use14,15,16,17,18,19. Our study showed the preliminary evidence of brief alcohol intervention in reducing alcohol use and slightly increasing abstinence among smokers, including most with low or moderate alcohol consumption. Three reasons could explain the small effect in increasing tobacco abstinence in the present study. First, our literature review indicated that 4 previous similar RCTs in heavy drinkers showed the effectiveness of alcohol control intervention for greater abstinence14,16,17,18,19. The counselling approach in reducing alcohol use for smokers with heavy drinking may not show the similar effect on smoking cessation outcomes in smokers with social or moderate drinking. Second, although the intervention group showed lower AUDIT scores and alcohol consumption at follow-up, our posteriori logistic regression analysis shows that only the reduction in STACS, but not reduction in AUDIT, was associated with higher tobacco abstinence. These findings suggest that rather than focusing on alcohol consumption or dependence, future studies should address the drinking problems and high-risk drinking behaviors mentioned in STACS (e.g. coping with the urge to smoke and craving for cigarettes that are triggered by alcohol). Third, as we recruited service users from ICSC, all participants were receiving conventional and multiple sessions of SC counselling. Our previous evaluation study showed that ICSC’s usual SC treatment led to a high tobacco abstinence in both short-term and long-term27. Therefore, the brief alcohol intervention might only have a small additional effect, if any, on further increase in tobacco abstinence. Further studies in comparing the intervention effect between smokers with and without conventional SC intervention are warranted. Moreover, considering health behaviour change is challenging36, especially we aimed to change both tobacco and alcohol use, participants in the intervention group might feel more difficulty to cope with 2 behaviours than the control group. Our findings showed that, although the intervention group received the additional brief alcohol intervention, the brief alcohol intervention did not compromise tobacco abstinence.

Our results showed that our brief alcohol intervention is potentially effective in reducing both AUDIT score and alcohol consumption. Also, the intervention group shows lower alcohol consumption than the control group at the 2-month follow-up, with similar effect size (mean difference 1.5 alcohol units/week, equivalent to 15 gram of alcohol/week) to general brief intervention for people with hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption shown in the recent Cochrane review (mean difference by 20 gram/week)37. One possible explanation for these findings is our intervention integrated both person-delivered and mobile health (mHealth) intervention components while previous studies examined person-delivered interventions (e.g. counselling)14,16,17,18,19 or mHealth interventions (e.g. website, text messages)15 separately. By setting achievable alcohol control goals during the brief counseling and reminding participants through text-messages, we facilitated greater commitment to these goals, which may enhance the efficacy of the intervention. In our study, the brief alcohol intervention could have increased smokers’ awareness of their alcohol use and then further motivated them to pursue alcohol reduction or abstinence. More evidence in supporting the effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions from full trials on smokers with low or moderate alcohol consumption are needed.

Our pilot RCT showed that our integrated brief alcohol intervention was highly feasible in several areas. First, our recruitment rate of 47.2% was higher than 2 previous pilot RCTs14,16 which were 39.1% and 36.1%, respectively. Similarly, our retention rate of 90.0% was higher than 2 previous pilot RCTs14,15 and 2 RCTs17,19, ranging from 41.1 to 79.2%. Second, the required time for intervention delivery was short, thereby allow counsellors to embed the brief alcohol intervention in the conventional SC treatment. Third, high compliance (100%) was found across 4 (short video or health advice, brief counselling, education leaflet, personalized WhatsApp messages) out of the 5 intervention components, indicating that counsellors were able to deliver most of them during the conventional SC treatment. Counsellors can deliver the health advice flexibly via a short video or brief counselling, depending on participants’ enrolment method. However, low compliance (31.3%) in delivering the brief advice based on AUDIT was found, probably because this standard alcohol advice may not fit in a SC treatment and did not address the diversified goals of alcohol control (e.g. abstain from alcohol or reduce alcohol). Moreover, all participants in the intervention group agreed to receive the WhatsApp messages. Half (49.0%) of them read most to all contents of the WhatsApp messages and half (56.9%) of them agreed the frequency of the WhatsApp messages was appropriate. These results support the feasibility of using WhatsApp messages as one of the intervention components in alcohol control. However, the modest acceptability reflected that the personalized advice was not practical nor suitable for changing their alcohol use as we proposed. Also, some might not have high intention or motivation to change their alcohol use during SC. Future trials need to better address the alcohol-related smoking relapse risk and improve the text-messages. For example, counsellors can send the text messages at weekends when most people consume alcohol and attend drinking occasions, or track participants’ tobacco and alcohol consumption through m-health tools and provide more personalized text messages.

Our trial had some limitations. First, the participation of biochemically validated tobacco abstinence was low (11/55 = 20%) at 2-month follow-up. The whole intervention period coincided with the 5th wave of COVID-19 outbreak in Hong Kong. Some participants refused biochemical validation because of hygiene concerns. Second, infection control measures, including mandatory closures of bars and nightclubs, were implemented throughout the whole study period, which might have also influenced alcohol use in the participants. Third, low compliance (7/51 = 13.7%) was found for delivering the short video. Many participants preferred remote enrollment in this study remotely due to hygiene concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, counsellors were only able to play the short video to 7 participants in the intervention group who enrolled in person. Although we sent the short video to all participants in the intervention group via WhatsApp messages, we did not assess whether participants watched the video during the designated intervention period. Future studies should assess whether participants watch the video on their own when receiving the intervention remotely. Fourth, we did not measure the intention to reduce alcohol use nor use of NRT and other SC medications which could potentially influence the treatment outcomes. Future trials should assess participants’ intention on both smoking cessation and alcohol control, perceived importance and difficulty to reduce alcohol use, and the use of SC pharmacotherapy. Furthermore, given the limited personnel and resources in this pilot study, counsellors performed both subject recruitment and intervention delivery roles which may have potentially introduced bias. Future studies should assign separate personnel for recruitment and intervention delivery. Moreover, conducting the posteriori t-tests after the mixed model may increase the chance of Type I error. Last, we developed STACS based on our qualitative interview findings, but its validity in assessing the risk of smoking relapse due to alcohol use is not certain.

Conclusions

We have shown the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary evidence of efficacy of a brief alcohol intervention during conventional SC treatment to increase tobacco abstinence and reduce alcohol use. Future studies should modify the intervention by addressing the drinking problems and behaviors that lead to smoking lapse and relapse. Evaluation of the intervention in a full trial is warranted.

Data availability

The data in this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

U.S. Centers for disease control and prevention. Behav. Risk Factor Surveill. Syst. Web Enabled Anal. Tool.

Höhne, B., Pabst, A., Hannemann, T. V. & Kraus, L. Patterns of concurrent alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis use in Germany: Prevalence and correlates. Drugs Educ. Prev. Polic. 21, 102–109. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2013.812614 (2014).

Noh, J. W., Kim, K. B., Cheon, J., Lee, Y. & Yoo, K. B. Factors associated with single-use and co-use of tobacco and alcohol: A multinomial modeling approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 3506. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193506 (2019).

Pengpid, S. & Peltzer, K. Trends in concurrent tobacco use and heavy drinking among individuals 15 years and older in Mongolia. Sci. Rep. 12, 16639. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21094-7 (2022).

Witvorapong, N. & Vichitkunakorn, P. Investigation of tobacco and alcohol co-consumption in Thailand: A joint estimation approach. Drug Alcohol Rev. 40, 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13128 (2021).

Frie, J. A., Nolan, C. J., Murray, J. E. & Khokhar, J. Y. Addiction-related outcomes of nicotine and alcohol co-use: New insights following the rise in Vaping. Nicotine Tob. Res. 24, 1141–1149. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntab231 (2022).

Van Amsterdam, J. & Van Den Brink, W. The effect of alcohol use on smoking cessation: A systematic review. Alcohol 109, 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2022.12.003 (2023).

Gulliver, S. B. et al. Interrelationship of smoking and alcohol dependence, use and urges to use. J. Stud. Alcohol 56, 202–206. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1995.56.202 (1995).

Rohsenow, D. J. et al. Effects of alcohol cues on smoking urges and topography among alcoholic men. Alcoholism Clin. Exp. Res. 21, 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.1997.tb03735.x (1997).

Drobes, D. J. Cue reactivity in alcohol and tobacco dependence. Alcoholism Clin. Exp. Res. 26, 1928–1929. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000374-200212000-00026 (2002).

Cunningham, M. et al. Smoking cessation guidelines for Australian general practice. Aus. Fam. Phys. 34 https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.368194179866187 (2020).

Clinical practice guideline treating tobacco use and dependence 2008 update panel, liaisons, and staff. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Am. J. Prev. Med. 35, 158–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009 (2008).

Optimal therapy initiative, department of family and community medicine. University of Toronto. Smok. Cessat. Guidelines https://www.smoke-free.ca/pdf_1/smoking_guide_en.pdf (2000).

Ames, S. C., Pokorny, S. B., Schroeder, D. R., Tan, W. & Werch, C. E. Integrated smoking cessation and binge drinking intervention for young adults: A pilot efficacy trial. Addict. Behav. 39, 848–853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.001 (2014).

Kahler, C. W. et al. A digital smoking cessation program for heavy drinkers: Pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Form. Res. 4, e7570. https://doi.org/10.2196/formative.7570 (2020).

Lim, A. C. et al. A brief smoking cessation intervention for heavy drinking smokers: Treatment feasibility and acceptability. Front. Psychiatry 9, 362. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00362 (2018).

Correa-Fernández, V. et al. Combined treatment for at-risk drinking and smoking cessation among Puerto Ricans: A randomized clinical trial. Addict. Behav. 65, 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.10.009 (2017).

Kahler, C. W. et al. Addressing heavy drinking in smoking cessation treatment: A randomized clinical trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 76, 852–862. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012717 (2008).

Toll, B. A. et al. A randomized trial for hazardous drinking and smoking cessation for callers to a quitline. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 83, 445–454. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038183 (2015).

Lynch, K. L., Twesten, J. E., Stern, A. & Augustson, E. M. Level of alcohol consumption and successful smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob. Res. 21, 1058–1064. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nty142 (2019).

Shariati, H. et al. Changes in smoking status among a longitudinal cohort of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Vancouver, Canada. Drug Alcohol Depend. 179, 370–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.07.025 (2017).

Tobacco and alcohol control office. Info-Station. https://www.taco.gov.hk/t/english/infostation/infostation_sta_01.html (2024).

Centre for health protection, & department of health, the government of the Hong Kong special administrative region. Report of Population Health Survey 2020-22 (Part I). https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/dh_phs_2020-22_part_1_report_eng_rectified.pdf (2023).

Wu, S. Y. et al. Tobacco control policy-related survey 2020. https://www.smokefree.hk/uploadedFile/COSHRN_E29.pdf (2021).

Ho, R., Fok, P. & Chan, H. Pattern and determinants of alcohol and tobacco co-use and its relationship with smoking cessation in Hong Kong. Tob. Prev. Cessat. 7, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.18332/tpc/132288 (2021).

Centre for health protection & department of health, the government of the Hong Kong special administrative region. Alcohol screening and brief intervention – A guide for use in primary care. https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/dh_audit_2017_alcohol_guideline_en.pdf (2017).

Mak, T. S. T. et al. Development of a brief alcohol intervention for smoking cessation services: A qualitative study on drinking smokers and health care professionals. Society For Research On Nicotine & Tobacco 29th Annual Meeting. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.srnt.org/resource/resmgr/conferences/2023_annual_meeting/documents/SRNT23_Rapid_Abstracts__1_.pdf (2023).

Chan, S. S. C., Leung, D. Y. P., Chan, H. C. H. & Lam, T. H. An evaluative study of the integrated smoking cessation services of Tung Wah group of hospitals. https://icsc.tungwahcsd.org/files/file/20180326/20180326095249_10948.pdf (2011).

Eldridge, S. M. et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ i5239. (2016).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. (eds) Handbook of Self-Determination Research (University Rochester, 2004).

Babor, T. F., Higgins-Biddle, J. C., Saunders, J. B. & Monteiro, M. G. AUDIT: the alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary health care. (2001).

Borland, R., Yong, H. H., O’Connor, R. J., Hyland, A. & Thompson, M. E. The reliability and predictive validity of the heaviness of smoking index and its two components: Findings from the international tobacco control four country study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 12, S45–S50. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntq038 (2010).

Cropsey, K. L. et al. How low should you go? Determining the optimal cutoff for exhaled carbon monoxide to confirm smoking abstinence when using cotinine as reference. Nicotine Tob. Res. 16, 1348–1355. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntu085 (2014).

Milosevic, I., Levy, H. C., Alcolado, G. M. & Radomsky, A. S. The treatment acceptability/adherence scale: Moving beyond the assessment of treatment effectiveness. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 44, 456–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2015.1053407 (2015).

Xiang, X., Kayser, J., Turner, S., Ash, S. & Himle, J. A. Layperson-supported, web-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in older adults: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e53001 (2024).

Heckman, B. W., Mathew, A. R. & Carpenter, M. J. Treatment burden and treatment fatigue as barriers to health. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 5, 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.004 (2015).

Kaner, E. F. et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD004148. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub4 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express our appreciation to all participants in the trial, and the staff from Tung Wah Group of Hospitals Integrated Centre on Smoking Cessation for their assistance. The authors would also like to thank the research staff from the Smoking Cessation Research Team and the Gerontechnology Team, School of Nursing, The University of Hong Kong, for their contributions and support to this project.

Funding

This work was supported by Health and Medical Research Fund (HMRF), Health Bureau, Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (ref no. 04190388). The funding body has no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis and interpretation, writing of the report or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yee Tak Derek Cheung: Conceptualisation; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing - review & editingTin Shun Titan Mak: Conceptualisation; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Validation; Visualization; Writong - original draft; Writing - review & editingTzu Tsun Luk: Conceptualisation; Resources; Writing - review & editingKam Wing Joe Ching: Conceptualisation; Data curation; Investigation; Project administration; Resources; SupervisionNga Ting Grace Wong: Conceptualisation; Data curation; Investigation; Project administration; Resources; SupervisionHelen Ching Han Chan: Conceptualisation; Data curation; Investigation; Project administration; Resources; SupervisionMan Ping Wang: Conceptualisation; Resources; Writing - review & editingTai Hing Lam: Conceptualisation; Resources; Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and informed consent

This study was approved by Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (reference number: UW 21–347). All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheung, Y.T.D., Mak, T.S.T., Luk, T.T. et al. A brief alcohol intervention during smoking cessation treatment in daily cigarette smokers: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 14, 31912 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83405-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83405-4