Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) plus chemotherapy have become the standard of care for first-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with EGFR/ALK negative. However, there is no clear second-line treatment option after first-line treatment failure. To investigate the efficacy and safety of ICIs alone or in combination rechallenge treatment after first-line ICIs plus chemotherapy progression in advanced NSCLC. We retrospectively analyzed the cases of patients who received ICIs alone or in combination rechallenge treatment after first-line ICIs plus chemotherapy progression in advanced NSCLC at Hunan Cancer Hospital between January 2020 and May 2024. We evaluated the effects of continued immunotherapy on patients’ objective response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR), progression-free survival (PFS), and adverse events after first-line treatment progression, and analyzed the relationship between outcomes and clinical characteristics. A total of 154 patients were included, with 146 patients developing resistance, 8 patients showing no progression. The ORR was 16.44%, the DCR was 68.49%, and the median PFS was 4.6 months. Patients treated with the new immune drug therapy had longer PFS than those treated with the original immunotherapy (5.0 months vs. 3.7 months, p = 0.0438). The PFS in patients receiving ICIs plus targeted therapy was significantly longer than that in patients who receiving ICIs alone, chemo-ICIs plus targeted therapy and ICIs plus chemotherapy (chemo-ICIs) (5.7 months vs. 3.6 months vs3.2 months vs. 2.9 months, p = 0.0086). Multivariate analysis showed that treatment regimen was a risk factor for immune rechallenge PFS, but there was no statistical correlation between gender, age, smoking history, pathological type, intermittent treatment or first-line drug resistance and immune rechallenge PFS. Our findings suggest that selecting ICIs plus targeted therapy may improve PFS in patients with advanced NSCLC after first-line chemo-ICIs progression. while replacement with new BSAb/PD-1 may be more beneficial to patients. However, there is a lack of large sample randomized controlled studies and evidence-based medical evidence, and more clinical studies are needed to further confirm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, immunotherapy has made great progress in the field of cancer, bringing more new survival hopes to cancer patients1. Tumor immunotherapy is to activate immune cells in the body, enhance the anti-tumor immune response, and specifically remove the small residual tumor lesions, inhibit tumor growth, and break immune tolerance2. Chemotherapy can activate immune response by releasing tumor cell antigen, regulating T cell function, reconstructing immune microenvironment and reducing immunosuppressive cells, which has a synergistic effect with immunotherapy3. Multiple clinical studies4,5,6,7,8 (KEYNOTE-189、IMpower150、KEYNOTE-407 ect.) show that chemo-ICIs can significantly improve overall survival and progression-free survival in patients compared with chemotherapy alone9.

Chemo-ICIs have become the standard of care for first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC with EGFR/ALK negative10,11,12. However, there is no clear second-line treatment option after first-line failure9. This study retrospectively analyzed the cases of patients who received ICIs alone or in combination rechallenge treatment after first-line chemo-ICIs progression in advanced non-small cell lung cancer at Hunan Cancer Hospital between January 2020 and May 2024, aiming to analyze the efficacy and safety of ICIs alone or in combination rechallenge treatment after first-line chemo-ICIs progression in advanced NSCLC.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

We retrospectively analyzed the cases of patients who received ICIs alone or in combination therapy after first-line chemo-ICIs progression in advanced non-small cell lung cancer at Hunan Cancer Hospital between January 2020 and May 2024. Research criteria include: (1) Patients ≥ 18 years of age. (2) The pathological diagnosis is advanced NSCLC. (3) Patients with advanced NSCLC who respond to first-line chemo-ICIs and continue to receive ICIs alone or in combination after tumor progression. Chemotherapy, targeted therapy or radiation therapy were allowed between immunotherapies. Exclusion criteria include: unblinded patients in clinical trials who cannot determine whether to use ICIs, and patients whose personal information is incomplete.

In order to better understand the details of the patient’s medication, we collected the information of the patient’s gender, age, smoking history, pathological type and treatment regimen. Subsequently, we divided the patients into four groups according to the treatment regimen that was immunotherapy rechallenged after tumor progression, including chemo-ICIs, ICIs plus targeted therapy, chemo-ICIs plus targeted therapy, and ICIs alone. Among them, the immune drugs include PD-1, PD-L1 and Bispecific monoclonal antibody (BSAb). PD-1 includes sintilimab, camrelizumab, pembrolizumab, tislelizumab, and toripalimab. PD-L1 includes atezolizumab and durvalumab. BSAb included cadonilimab and IBI318 (a recombinant fully human immunoglobulin G1 bispecific antibody directed against PD-1 and PD-L1). Chemotherapy drugs include gemcitabine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, pemetrexed, cisplatin, carboplatin, nedaplatin, Targeted drugs include: anlotinib, lenvatinib and recombinant human endostatin.

The research project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hunan Cancer Hospital, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects or their legal guardians. All patients in the study records adhered to the provisions of 《Declaration of Helsinki》. Patient data collected during follow-up were in compliance with relevant data protection and privacy regulations.

Evaluation index

The main measures include: Objective Response Rate (ORR), Disease Control Rate (DCR), Progress Free Survival (PFS), and Adverse Events (AE). Solid tumor response Evaluation criteria (RECIST, version1.1) were used to evaluate the patient’s treatment effect, including complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and disease progression (PD). ORR was the sum of CR and PR, and DCR was the sum of ORR and SD. PFS is defined as the time from the start of the first treatment to tumor progression or death from any cause. We graded adverse events according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Adverse Events Evaluation Criteria Version 5.0(CTCAE).new immune drugs were ICIs that the patient had not received as part of previous treatment.The last follow-up was on May 31, 2024.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 26.0 software was used for statistical analysis. Patient characteristics were represented by the number of cases (%), patient age was represented by mean ± standard deviation, and comparison between groups was performed by Chi-square test or Fisher exact test. The median PFS was evaluated by Kaplan Meier curve, and the median PFS between subgroups was tested by log-rank. SPSS 26.0 software was used for univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis to determine the odds ratio (OR) of PFS for continued immunotherapy after tumor progression under different exposure factors (gender, age, smoking history, treatment regimen, pathological type, etc.). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

From January 2020 to May 2024, we enrolled 154 patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. In terms of the treatment regimen of ICIs rechallenge after tumor progression, 82 patients received chemo-ICIs, 46 patients received ICIs plus targeted therapy, 15 patients received chemo-ICIs plus targeted therapy, and 11 patients received ICIs alone rechallenge. In the whole study group, the average age of the patients was 60.88 ± 8.14 years, the median age of the patients was 61 years and the proportion of patients under 65 years old (68.18%) was higher. 121 patients (78.57%) were male, 102 patients (66.23%) had a history of smoking, and 85 patients (55.19%) had lung squamous cell carcinoma. In terms of PD-L1 expression (antibody type 22C3), 25 cases were negative (< 1%), 32 cases were low expression (≥ 1%, < 50%), and 17 cases were high expression (≥ 50%). 147 patients (95.45%) had a PS score of 0 or 1 before receiving 2-line therapy. Primary drug resistance occurred in 69 patients (44.81%) and secondary drug resistance occurred in 85 patients (55.19%). The main characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Efficacy analyses

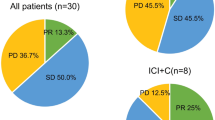

In the treatment regimen of rechallenge immunotherapy, a total of 146 patients developed drug resistance, no patients developed CR, 24 patients developed PR, 76 patients developed SD, and the total ORR was 16.44% and DCR was 68.49%. The ORR of chemo-ICIs plus targeted therapy was the highest (26.67%), and the ORR of ICIs alone was the lowest (10.00%). In terms of DCR, ICIs plus targeted therapy was the highest (88.37%), while chemo-ICIs was the lowest (57.69%), as shown in Table 2. In the entire study group, a total of eight patients showed no progression, with a median PFS of 4.6 months. From the perspective of rechallenge immunotherapy regimens after tumor progression, the median PFS of ICIs plus targeted therapy was the longest (5.7 months), followed by ICIs alone (3.6 months), chemo-ICIs (3.2 months), and the median PFS of chemo-ICIs (2.9 months).

Additionally, we analyzed PFS by different subgroups. In the rechallenge immunotherapy regimen, patients who received new immune drugs had a longer PFS (5.0 months vs. 3.7 months, P = 0.0438) than those who received original immune drugs, indicating that switching immune drugs was beneficial to patients. However, there was no significant correlation between the duration of first-line treatment maintenance and whether intermittent treatment was given before immune therapy rechallenge and PFS. See Fig. 1.

Among the 71 patients treated with new immune drugs, the Chemo-ICIs group had the most ICI switching cases (29 cases), followed by ICIs + Targeted group (27 cases). Chemo-ICIs + Targeted group had the least number of ICI switching cases (5 cases). The details are shown in Fig. 2. we classified the 71 patients who were treated with new immune drugs according to the use of PD-1 and PD-L1 in the first-line treatment regimen. There were 68 patients (95.77%) in the PD-1 combined with chemotherapy group and 3 patients (4.23%) in the PD-L1 combined chemotherapy group. In terms of receiving new immune drugs, 24 patients (35.29%) in the 68 PD-1 combined with chemotherapy group continued to receive PD-1 retreatment, and 14 patients (20.59%) received PD-L1 retreatment, 30 patients (44.12%) were treated with BSAb. Among the 3 patients in the PD-L1 combined with chemotherapy group, no patient continued to receive PD-L1 retreatment, 1 patient (33.33%) received PD-1 retreatment, and 2 patients (66.67) received BSAb retreatment, as shown in Fig. 3. In the PD-1 combined with chemotherapy group, BSAb treatment had the longest PFS (5.8 months), followed by PD-1 treatment (4.9 months), and PD-L1 treatment (2.5 months). In the PD-L1 combined with chemotherapy group, PFS was longer in the BSAb retreatment group than in the PD-1 group (4.3 vs. 1.5 months).

Adverse drug events

In our study, a total of 84 patients experienced adverse events of all grades. The incidence of adverse events was the highest in the ICIs group (58.33%), followed by the Chemo-ICIs group (54.88%) and the ICIs + Targeted group (53.19%). The Chemo-ICIs + Targeted group had the lowest incidence of adverse reactions (43.75%). Among the grade ≥ 3 adverse events, the incidence of myelosuppression (4 cases) and pneumonitis (3 cases) was higher in the Chemo-ICIs group. The incidence of myelosuppression (3 cases), pneumonia (3 cases), hepatitis (3 cases) and severe fatigue (2 cases) was higher in the ICIs + Targeted group. Adverse events in the ICIs group included hepatic injury (1 case), thyroiditis (1 case) and pneumonia (1 case), while adverse events in the Chemo-ICIs + Targeted group included pneumonia (1 case), hypophysitis (1 case) and fatigue (1 case). As shown in Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

The correlation between patient gender, age, smoking history, pathological type, treatment scheme, and first-line resistance in PFS was analyzed in Table 4. Univariate logistic regression analysis suggested that treatment scheme and first-line resistance may be important influencing factors on PFS of patients undergoing rechallenge immunotherapy. In order to better reflect the real situation, two indicators with statistical significance (P < 0.05) were included in the multivariate analysis. The results suggest that the chemo-ICIs scheme has statistically significant impact on PFS of patients undergoing rechallenge immunotherapy (OR = 0.669 [0.119, 0.952], p = 0.040), followed by patients receiving ICIs plus targeted therapy (OR = 0.350 [0.122, 1.000], p = 0.050). However, there is no statistically significant correlation between PFS and patient gender, age, smoking history, pathological type, interval treatment.

Discussion

This study included patients who recieved ICIs rechallenge after progression on first-line chemo-immunotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Compared to the drug regimen of discontinuing immune-related adverse events or completing the prescribed course of treatment and then re-immunotherapy, the clinical data for this group of patients is more limited13. Fortunately, our study can provide certain clinical evidence for the treatment of these patients.

In our study, 154 patients were included, 146 patients showed drug resistance and 8 patients showed no progression, with ORR of 16.44%, DCR of 68.49%, and median PFS of 4.6 months, which was basically consistent with the previously reported clinical trial data on immune rechallenge of NSCLC14,15. When we grouped patients according to the treatment regimen after first-line chemo-ICIs therapy progression, we found significant differences, with a median PFS of 5.7 months for patients in ICIs combined targeted therapy and 2.9 months for patients in chemo-ICIs therapy.

Up to now, there is no clear second-line treatment plan for advanced NSCLC patients after cancer progression with first-line chemo-ICIs therapy. Many patients receive chemotherapy or targeted therapy after progression with first-line chemo-ICIs therapy. A multicenter retrospective study included 124 patients with advanced NSCLC who had progressed through first-line chemo-ICIs therapy and were given second-line chemotherapy rechallenge with platinum, paclitaxel +/− antiangiogenic therapy, or other chemotherapy agents (including gemcitabine, vinorelbine, or pemetrexel)9. The results showed that patients receiving second-line chemotherapy had a DCR of 42.5%, a mOS of 8.1 months, and a median PFS of 2.9 months. This is basically consistent with our findings.

In a multicenter clinical study evaluating cabozantinib combined with atezolizumab in advanced solid tumors16, the ORR of cabozantinib combined with atezolizumab in this study was 19% in patients with advanced NSCLC who had previously received immunotherapy. This has shown encouraging clinical efficacy. This study preliminarily confirmed the feasibility of receiving ICIs plus targeted therapy after progression in advanced NSCLC patients who had previously received immunotherapy. In our study, patients with ICIs plus targeted therapy had the best PFS, which was significantly longer than ICIs alone, chemo-ICIs targeted therapy and chemo-ICIs therapy (5.7 months vs. 3.6 months vs. 3.2 months vs. 2.9 months, p = 0.0086). The results of our study are surprising and provide a new basis for the selection of treatment for advanced NSCLC after immunotherapy resistance.

We found that patients treated with ICIs + Targeted therapy had the best PFS, and this favorable response rate may be due to the combination partners, and the combined targeted drugs are all targeted anti-vascular drugs. The infiltration of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment will affect the effect of immunotherapy. Because the abnormal blood vessels generated by tumors affect the infiltration and function of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment, and then inhibit the immune microenvironment, resulting in easy leakage of blood vessels and reduced adhesion and infiltration of immune cells. Eventually, the function of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes is impaired17. Targeted anti-vascular drugs can improve immune cell infiltration and reverse immunosuppression through a variety of ways, thereby synergistically enhancing the efficacy of ICIs18. At the same time, ICIs can not only inhibit abnormal tumor angiogenesis, but also regulate the immune microenvironment, providing a suitable environment for ICIs therapy19. The combination of targeted anti-vascular drugs and ICIs can form a synergistic effect between vascular normalization and immune remodeling. Therefore, ICIs combined with targeted anti-vascular drugs has a favorable response rate.

In addition to the above treatment options, we also considered interval treatment. interval treatment refers to the interspersed treatment that patients receive between primary immunotherapy and immunotherapy rechallenge, including chemotherapy, targeted therapy or radiotherapy20. Multiple clinical studies21,22,23have shown that interval treatment may bring survival benefits to patients with advanced NSCLC who receive immune rechalleng after resistance to first-line immunotherapy. A multicenter retrospective study conducted by Gobbini15. which included 144 patients with advanced NSCLC who received immunotherapy rechallenge, also showed that patients who received interval treatment between immunotherapy sessions had longer PFS (5.8 vs. 3.0 months). However, in our study, we did not find that interval treatment brought significant benefits to patients, which may be due to the small clinical sample in our study, which led to the difference.

In this study, we also found that patients treated with new immune drugs had a longer PFS (5.0 months vs. 3.7 months, p = 0.0438) than those treated with original immune drugs. When the first-line treatment was PD-1 combined with chemotherapy, patients treated with BSAb benefited the most, followed by PD-1, and PD-L1 benefited the least. The same is true for immune benefit when PD-L1 combined with chemotherapy is used as first-line treatment. This result has not been mentioned in previous studies. Kitagawa24retrospectively studied 17 patients with advanced NSCLC who received different PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, and 10 of them (58.8%) achieved PR or SD. However, Watanabe25 reported that switching to a different PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor did not yield clinical benefits. Theoretically, the immune mechanisms of different immune checkpoint inhibitors are not entirely the same, and using different ICI for rechallenge can reduce irAE to some extent while achieving better efficacy. Our study also supports this result.

The effectiveness of immune retherapy in patients who have discontinued treatment due to immune resistance has not been fully evaluated. there is currently a lack of large sample randomized controlled studies and evidence-based medical evidence, and more clinical data studies are needed to further confirm. Encouragingly, our study provides evidence for this. Our results show that treatment regimen is a risk factor for immunotherapy rechallenge PFS, and there is no statistical correlation between gender, age, smoking history, pathological type, intermittent treatment or first-line drug resistance and immunotherapy rechallenge PFS. For medical staff, the choice of treatment regimen is also the direction of concern for NSCLC patients after immune resistance. Our study provides a new idea and basis for the selection of immunotherapy rechallenge regimen. In the immunotherapy rechallenge regimen, we recommend ICIs plus targeted therapy, which includes anlotinib, lenvatinib and recombinant human endostatin.

Limitations

Our study also has some limitations. First, it is a retrospective, non-randomized analysis, conducted in a single institution, and the study did not explore markers for rechallenging treatment. The number of cases of PD-L1 combined with chemotherapy in the first-line treatment is small. Although patients in the BSAb retreatment group benefit more than those in the PD-1 group, there is a lack of large sample clinical studies. We believe that in the future, more evidence-based medical evidence will further confirm this view. In short, the ICI rechallenge is good for some groups. The choice of treatment plan is the key to prolong PFS, and combined targeted therapy has the advantage of PFS. In the future, it is still necessary to explore the mechanism of immune resistance, different treatment modes, whether immunotherapy can be extended or resensitized, and how to deal with immune resistance individually.

Conclusions

Our study findings suggest that using ICIs plus targeted therapy after progression in patients with advanced NSCLC who have received first-line chemo-ICIs may increase their PFS, while switching to a new BSAb/PD-1 may be more beneficial for patients. This provides new evidence for the choice of treatment regimens for advanced NSCLC after immunotherapy resistance. However, there is a lack of large sample randomized controlled studies and evidence-based medical evidence, and more clinical studies are needed to further confirm.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available in the main text or figures, and others are available from the corresponding author. Individual participant data in the raw data are protected by data privacy laws. To request access, please contact the corresponding author (Fen Liu, E-mail: liufen@hnca.org.cn) and all requests will be responded to within 1 month.

References

Chen, P. et al. Non-small cell lung cancer in China. Cancer Commun. (Lond) 42(10), 937–970 (2022).

Wang, S. J., Dougan, S. K. & Dougan, M. Immune mechanisms of toxicity from checkpoint inhibitors. Trends Cancer. 9(7), 543–553 (2023).

Salas-Benito, D. et al. Paradigms immunotherapy combinations chemotherapy. Cancer Discov. 11(6), 1353–1367. (2021).

Rodriguez-Abreu, D. et al. Pemetrexed plus platinum with or without pembrolizumab in patients with previously untreated metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC: protocol-specified final analysis from KEYNOTE-189. Ann. Oncol. 32(7), 881–895. (2021).

Halmos, B. et al. Pembrolizumab + chemotherapy versus atezolizumab + chemotherapy+/-bevacizumab for the first-line treatment of non-squamous NSCLC: a matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Lung Cancer 155, 175–182 (2021).

Brahmer, J. R. et al. Five-year survival outcomes with nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer in CheckMate 227. J. Clin. Oncol. 41(6), 1200–1212 (2023).

Novello, S. et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in squamous non-small-cell lung cancer: 5-year update of the phase III KEYNOTE-407 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 41(11), 1999–2006 (2023).

Horn, L. et al. First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 379(23), 2220–2229 (2018).

Auclin, E. et al. Second-line treatment outcomes after progression from first-line chemotherapy plus immunotherapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 178, 116–122 (2023).

Ettinger, D. S. et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 3.2022, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 20(5), 497–530 (2022).

Planchard, D. et al. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 29(Suppl 4), v192–v237 (2018).

Gadgeel, S. et al. Updated analysis from KEYNOTE-189: pembrolizumab or placebo plus pemetrexed and platinum for previously untreated metastatic nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 38(14), 1505–1517. (2020).

Atkins, M. B. et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) consensus definitions for resistance to combinations of immune checkpoint inhibitors with targeted therapies. J. Immunother. Cancer 11(3) (2023).

Herbst, R. S. et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled tria. Lancet 387(10027), 1540–1550 (2016).

Gobbini, E. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors rechallenge efficacy in non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Clin. Lung Cancer 21(5), e497–e510 (2020).

Pal, S. K. et al. Cabozantinib in combination with atezolizumab for advanced renal cell carcinoma: results from the COSMIC-021 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 39(33), 3725–3736 (2021).

Chinese expert consensus on evaluation and treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer with negative driver genes after first-line immunotherapy resistance (2024 edition). Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 104(6), 411–426 (2024).

Wang, D. et al. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Med. 8(10), 4709–4721 (2019).

Liang, H. & Wang, M. Prospect of immunotherapy combined with anti-angiogenic agents in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 11, 7707–7719 (2019).

Tian, L. et al. Mutual regulation of tumour vessel normalization and immunostimulatory reprogramming. Nature 544(7649), 250–254 (2017).

Giaj, L. M. et al. Immunotherapy rechallenge after nivolumab treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the real-world setting: a national data base analysis. Lung Cancer 140, 99–106 (2020).

Xu, M. et al. Efficacy of rechallenge immunotherapy after rechallenge immunotherapy resistance in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 149(20), 17987–17995 (2023).

Feng, Y. et al. Efficacy and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorac. Cancer 14(25), 2536–2547 (2023).

Kitagawa, S. et al. Switching administration of anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies as immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge in individuals with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Case series and literature review. Thorac. Cancer 11(7), 1927–1933 (2020).

Watanabe, H. et al. The effect and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge in non-small cell lung cancer. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 49(8), 762–765 (2019).

Funding

This work is supported by the Hunan Provincial Health Commission Project (D202313017815) and Shandong Provincial natural fund project(ZR2022LZY013)and Shandong Provincial Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project (M-2022039) and Binzhou Medical College Traditional Chinese Medicine Discipline Integration Science and Technology Program (4ZYYKJ09).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GSY and XL was responsible for data sorting and manuscript writing, FL was responsible for data processing and manuscript review, ST and XTY was responsible for manuscript review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, G., Liu, X., Yu, X. et al. Analysis of ICIs alone or in combination rechallenged outcomes after progression from first-line ICIs plus chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep 15, 30 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83947-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83947-7