Abstract

In patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) whose symptoms improve with acid-suppression therapy, on-demand treatment could constitute maintenance therapy. This study investigated the comparative efficacy and safety of on-demand tegoprazan and proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy in GERD. From six university hospitals in the Daejeon-Chungcheong region, we enrolled patients with GERD who had experienced symptomatic improvement with acid-suppressive therapy and, using a randomization table, randomly allocated these participants to two groups: to receive either tegoprazan 50 mg + esomeprazole placebo or tegoprazan placebo + esomeprazole 20 mg, respectively. The primary endpoint of this study was the intergroup difference in patient satisfaction with on-demand therapy. Among the 69 participants who completed 8 weeks of on-demand therapy and rated patient satisfaction on a 5-point Likert scale, the tegoprazan and esomeprazole groups scored an average of 4.31 and 4.15 points, respectively, without any significant intergroup difference. In the tegoprazan group, 26.2% (182/694) of those with episodes experienced symptom improvement within 30 min, which is a significantly higher proportion compared to 16.1% (104/646) in the esomeprazole group. Compared to the esomeprazole group, the tegoprazan group had a significantly shorter time to symptom improvement overall and a significantly higher proportion of patients who improved within 30 min. No serious treatment-emergent adverse events were reported. Tegoprazan is effective as on-demand therapy for GERD and offers the expectation of faster symptom improvement than with PPIs. Clinical trial KCT0009296, registered at cris.nih.go.kr.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Montreal Global Consensus definition of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) encompasses symptoms caused by the reflux of gastric contents, including acid1. Though it is a common condition worldwide, epidemiological studies have revealed an increasing frequency of GERD in Asia2. The suppression of gastric acid secretion, primarily by using proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), is the cornerstone of GERD treatment. Following symptom improvement with 4- to 8-week PPI therapy, maintenance therapy with either half-dose or on-demand PPI therapy can be implemented3. In a meta-analysis that compared on-demand and half-dose PPI maintenance therapy, equivalent therapeutic efficacy was identified in patients with non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) or mild erosive esophagitis. Furthermore, the on-demand approach permits reduction of the PPI dosage4, which is advisable because long-term PPI use is associated with issues such as an increased risk of mineral and vitamin deficiencies, anemia, fractures, liver and kidney disease, infections (including enteric infection and pneumonia), dementia, and hypergastrinaemia5, and recent reports indicate a potentially increased incidence of various cancers, particularly gastric cancer6,7. Therefore, PPI dosage reduction, if feasible, is beneficial for patients.

On-demand therapy, a treatment approach where medication is administered based on symptom onset, can be highly effective when utilizing drugs that demonstrate rapid onset of action and prolonged efficacy. Potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CABs) can act on resting proton pumps, which eliminates the need for pre-meal dosing; moreover, they are characterized by the rapid increase of their plasma concentration, which ensures rapid onset of drug action, and have prolonged efficacy8,11,12. Thus, compared to PPIs, P-CABs may be more advantageous for on-demand therapy8. In patients with NERD, vonoprazan, a P-CAB, demonstrated superior efficacy than the placebo when used as on-demand therapy, and showed therapeutic efficacy equivalent to PPI maintenance therapy9,10. Since medication is administered after the onset of symptoms, patient satisfaction is likely to vary depending on the speed of symptom relief. Therefore, in on-demand therapy, the time to onset of the drug’s effect is the most critical factor. Tegoprazan, a P-CAB, is characterized by its particularly rapid onset of action (approximately 30 min)8, which is faster than that of other P-CABs and PPIs; this characteristic may be advantageous in on-demand therapy11,12. However, no study has validated the effectiveness of tegoprazan as on-demand therapy for patients with NERD or mild esophagitis.

The potency of P-CABs surpasses that of PPIs, and their rapid clinical efficacy has led to an increasing role for P-CABs in the treatment of GERD. Unlike a curable disease, GERD is a condition that requires ongoing management, and the potential long-term adverse effects of P-CABs remain a significant concern. P-CABs are relatively new drugs, and thus, research and investigation into their long-term safety is limited. However, as most of the long-term side effects of PPIs occur due to the suppression of gastric acid production, P-CABs may induce long-term adverse effects that are similar to that of PPIs. Thus, the demonstration of the usefulness of on-demand P-CAB therapy in GERD could present an excellent opportunity to reduce medication usage and enhance patient convenience. Therefore, to demonstrate the efficacy of tegoprazan as on-demand therapy for patients with NERD or mild esophagitis, this clinical trial was undertaken as an exploratory study that aimed to compare the therapeutic effects of tegoprazan and PPIs administered as on-demand therapy to patients with GERD who have responded to PPI treatment.

Materials and methods

Study population

In Republic of Korea, six university hospitals in the Daejeon-Chungcheong region enrolled patients with GERD who were at least 19 years old and had a history of heartburn and regurgitation for which they had received acid-suppressive therapy for at least 4 and 8 weeks for NERD and erosive reflux disease (ERD), respectively, and had experienced symptom improvement. All participants in this study had undergone upper gastrointestinal endoscopy within the past six months and were either diagnosed with erosive esophagitis or confirmed to have no organic diseases that could explain their symptoms. Owing to the lack of reference literature on the degree of symptom improvement following on-demand therapy, no specific calculation formula was applied. However, considering the patient pool of the participating institution and the standard recommendation for pilot studies to include an appropriate sample size of 10–30 participants per group, we initially planned to include 30 participants per group, and factoring in an anticipated dropout rate of 20%, we aimed to enrol a total of 76 participants.

The exclusion criteria for this clinical trial included: (1) inability to undergo upper gastrointestinal endoscopy; (2) inability to self-maintain clinical trial diaries; (3) the presence of oesophageal stricture, ulcer stricture, esophagogastric varices, Barrett’s oesophagus exceeding to ≥ 3 cm, eosinophilic esophagitis, active peptic ulcer, or gastrointestinal bleeding, as determined by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy; (4) history of surgery of the oesophagus, stomach, or duodenum; (5) history of, or scheduled to undergo, surgeries that affect gastric acid secretion, such as surgical upper gastrointestinal resection or vagotomy, though individuals who had undergone endoscopic simple perforation repair, appendectomy, cholecystectomy, or benign tumour resection were eligible to participate; (6) current treatment with atazanavir-, nelfinavir-, or rilpivirine-containing regimens; (7) history of hypersensitivity to PPIs, P-CABs, or benzimidazole derivatives; (8) history of malignancy within the past 5 years, though those in complete remission for more than 5 years without recurrence and those who had been tumour-free for more than 3 years following endoscopic resection were eligible; (9) those on continuous treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), antithrombotic agent during the trial period, though the pre-trial use of low-dose aspirin prophylaxis (< 100 mg per day) was allowed; (10) those with clinically significant disorders of the liver, kidney, cardiovascular, respiratory, endocrine, or central nervous systems; (11) those with abnormal laboratory test values at screening (blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine level, > 1.5 upper limit of normal [ULN]; total bilirubin levels and serum levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase and gamma glutamyltransferase, > 2 ULN); (12) pregnant or breastfeeding individuals, or those intending to conceive; (13) those requiring hospitalization for surgery or surgical treatment during the clinical trial period; and (14) those who could not provide informed consent for study participation.

Participants were discontinued and withdrawn from the clinical trial if they: (1) withdrew consent; (2) received treatments or medications that could affect the study outcomes without the directive of the attending physician during the clinical trial period; (3) were non-compliant with the physician’s instructions; (4) experienced adverse events that rendered further participation in the trial unfeasible; (5) were deemed unable to undergo follow-up assessments during the research period; (6) experienced change in conditions whereby continued participation in the trial was deemed unsafe or unethical by the researcher; (7) were deemed, by the researcher, to lack feasibility for continuation of the clinical trial.

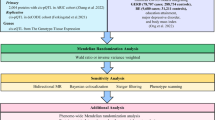

Study protocol and evaluation

Using a randomization table, the participants were randomly allocated to two groups to receive either tegoprazan 50 mg + esomeprazole placebo or tegoprazan placebo + esomeprazole 20 mg. The study participants received full dose of acid-suppressive therapy up until the point of enrollment. The study participants were instructed to discontinue the medication and use it only when symptoms occurred. Participants who experienced symptoms took the medication up to once per day. The primary endpoint of this study was the intergroup difference in patient satisfaction with on-demand therapy. Following the commencement of the study, the participants visited the hospital at weeks 4 and 8, and underwent assessments to evaluate the degree of symptom improvement and the occurrence of any adverse events (AEs; Fig. 1). The primary efficacy endpoint of patient satisfaction after 8 weeks of on-demand therapy was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale, and categorized as follows: very satisfied (5), satisfied (4), neither satisfied nor dissatisfied (3), dissatisfied (2), and very dissatisfied (1).

Secondary efficacy endpoints were evaluated as follows: (1) time until symptom improvement after medication administration, (2) the number of medications taken during on-demand therapy, (3) severity (intensity) and frequency of heartburn and acid reflux symptoms, assessed using a 5-point Likert scale to determine inter- and intragroup differences. Patients were instructed to record the time to symptom improvement after taking the medication in a diary that was to be submitted during outpatient visits. The dosage of the medication was verified by having patients submit any remaining medication during outpatient visits. The severity of heartburn and regurgitation was categorized based on the 5-point scale as: none (0); mild (minor symptoms are present, but can be ignored with effort: (1); moderate (symptoms cannot be ignored, but do not interfere with daily activities: (2); moderately severe (symptoms cause discomfort and interfere with daily activities: (3); and very severe (symptoms are so severe that daily activities are difficult to perform: (4). The frequency of heartburn and regurgitation was categorized according to the 5-point scale as: none (0), more than 1 day but less than 2 days per week (1), more than 2 days but less than 3 days per week (2), more than 3 days but less than 5 days per week (3), and more than 5 days per week (4).

Though tegoprazan 50 mg has been approved for the treatment of ERD and NERD, the appropriate on-demand dosage has not been ascertained. Esomeprazole is available in 20-mg and 40-mg formulations, both of which the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved for the treatment of GERD, whereas the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has designated only 20 mg as the standard dose. Additionally, a study published in 2004 that compared on-demand 20-mg esomeprazole treatment with 15-mg lansoprazole continuous treatment was referenced to establish the treatment dosage of esomeprazole at 20 mg13. During the clinical trial period, the following medications were prohibited: antacids including PPI, H2 antagonists, and P-CAB, antibiotics, probiotics, gastrointestinal motility regulators, gastrointestinal mucosal protectants, lower oesophageal sphincter relaxants, cholinergic agents, anticholinergic drugs, antispasmodic agents, psychoactive drugs, and systemic glucocorticoids.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 8.3 (SAS Institution Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Intergroup differences in proportions for categorical variables were analysed using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, whereas those in mean values for continuous variables were assessed using the t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. The statistical methods and results were validated in consultation with a statistician. The results were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Ethics statement

This clinical trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board (approval no. CNUH 2020-11-038) of the study institution, and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Korean Good Clinical Practice (KGCP), and other relevant regulations. The clinical trial was registered at cris.nih.go.kr (Registered date:2024/03/29, KCT0009296). The objectives of the trial and the characteristics of the investigational medicinal products was explained to potential participants in a private setting via an informed consent form. Only participants who understand the purpose and risks of the clinical trial and provided written consent were eligible to participate in the trial. Participants were informed that they may withdraw their consent to participate in the clinical trial at any time during the study. Furthermore, information regarding compensation for trial participants was provided. Data collected during the clinical trial were recorded in the Case Report Forms, and the confidentiality of all patient-related information was maintained.

Results

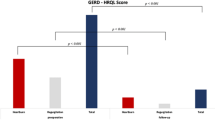

A total of 85 patients intended to participate in the study, and among them, 76 were enrolled in the study. Seven patients were excluded during screening as they did not meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and two patients subsequently requested that they be dropped from the study. Of the 40 and 36 participants who were allocated to the tegoprazan and esomeprazole groups, respectively, three in the tegoprazan group (no symptoms) and one in the esomeprazole group (safety was not evaluated) were excluded. Additionally, the efficacy evaluation was not possible for one and two participants in the tegoprazan and esomeprazole groups, respectively. Consequently, the final analysis included results from 36 and 33 participants (Fig. 2), and the mean ages were 56.6 and 61.2 years, respectively. There was no significant intergroup difference in the BMI, endoscopic grade of esophagitis, alcohol consumption status, symptom severity, or the type of PPI that was previously used. However, participants in the tegoprazan group were taller, heavier, and comprised a greater number of those who consumed alcohol (Table 1). At weeks 4 and 8, there was no significant intergroup difference in the overall satisfaction, assessed using a 5-point Likert scale (Table 2), and in changes in the frequency and severity of heartburn and regurgitation (Table 3). Despite no significant intergroup difference in overall satisfaction and symptom improvement, those in the tegoprazan group tended to experience faster symptom improvement. The proportion of episodes with symptomatic improvement within 30 min that was maintained for 24 h was significantly higher with tegoprazan. An episode was defined as any day on which heartburn or regurgitation occurred. There were a total of 694 and 646 episodes in participants in the tegoprazan and esomeprazole groups, respectively. In the tegoprazan group, 26.2% (182/694) of those with episodes experienced symptom improvement within 30 min, which is a significantly higher proportion compared to 16.1%(104/646) in the esomeprazole group. This trend of faster symptom improvement in the tegoprazan group remained significant when assessed at 30-minute intervals for up to 3 h (Fig. 3). No intergroup difference in study drug use was detected (Table 4). Adverse events were analysed in the safety set. No AEs occurred in the tegoprazan group, whereas 6 AEs occurred in the esomeprazole group, of which 5 patients who experienced mild AEs. The AEs in the esomeprazole group were considered irrelevant to the study drug. There was no serious AE or death during the study (Table 5).

Flowchart depicting patient enrolment and disposition in the study. Of the 85 patients who were screened, 76 were enrolled after excluding those who did not take any medication owing to the absence of symptoms, those who could not be monitored for adverse events, or in whom efficacy could not be evaluated. The final analysis included 69 participants.

Discussion

On-demand therapy for GERD has proven usefulness as a long-term maintenance strategy. However, in actual clinical practice, some patients prefer to take their medication continuously. This preference is often due to the considerable delay between symptom onset and symptom improvement after medication intake. Therefore, the success of on-demand therapy critically depends on the rapid improvement of symptoms. P-CABs are novel acid-suppressing drugs that can act on resting proton pumps. Unlike PPIs, P-CABs can be taken without regard to meals, which makes them advantageous for on-demand therapy where medication needs to be taken after the onset of symptoms. Particularly, tegoprazan, with the fastest pharmacological action among the P-CAB class, is highly suitable for on-demand therapy8. However, to date, no studies have demonstrated the efficacy of tegoprazan in on-demand therapy. Considering this, the authors designed the present study to evaluate the effectiveness of tegoprazan in on-demand therapy for patients with GERD.

Regarding the primary endpoint of this study to ascertain the difference between P-CAB and PPI on-demand therapy, the authors hypothesized that P-CAB would yield higher patient satisfaction. However, the actual study results showed no significant difference between the two groups. Several explanations for these findings are possible. First, when used in adequate dosages over a sufficient period, the difference between P-CAB and PPI may not be substantial. Previous studies that compared esomeprazole and tegoprazan in erosive esophagitis did not report significant differences in the healing rate of erosive esophagitis or intergroup differences in symptom improvement14. In comparative studies of the treatment of peptic ulcers with various types of PPIs, no significant differences in ulcer healing rates among the PPIs have been reported15. Therefore, it can be anticipated that when both P-CAB and PPI are used in sufficient dosages for an adequate period, and patient satisfaction is subsequently assessed, no significant intergroup differences would be observed. Secondly, it is possible that no significant difference was observed because on-demand therapy was implemented as maintenance therapy in patients whose symptoms had already improved significantly. In fact, three patients assigned to the tegoprazan group experienced no symptom during the clinical trial period and were consequently excluded from the final analysis. The actual clinical symptoms were not severe, as evidenced by study drug use during the first 4 weeks. The mean (SD) number of used study drug is 10.64 (7.96) in the tegoprazan group and 10.15 (10.52) in the esomeprazole group, with median values of 10 and 7, respectively. During the subsequent 4 weeks, the mean (SD) consumption was 9.47 (7.92) tablets for the tegoprazan group and 10.67 (9.23) tablets for the esomeprazole group, with median values of 7 and 8, respectively (Table 4).

If the acid-suppressive effects of PPI and P-CAB show minimal differences in patients with mild symptoms or after a sufficient period, the primary factor distinguishing the therapeutic efficacy in on-demand therapy would likely be the difference in the onset of action between the medications. The proportion of patients whose symptoms improved within 30 min of medication intake was significantly higher in the tegoprazan group as compared to that in the esomeprazole group. This difference persisted and was consistently observed up to 3 h post-medication intake. Fock et al. argued that differences in pharmacokinetics can translate into differences in clinical outcomes16. Furthermore, this study confirmed that the group treated with tegoprazan, which has a rapid onset of action and convenient administration irrespective of meals, demonstrated faster clinical improvement. Though this study did not demonstrate a substantial difference in symptom improvement or satisfaction between the esomeprazole group and the tegoprazan group, it is evident that the rapid symptom improvement observed with tegoprazan can ultimately lead to improved quality of life and increased patient satisfaction.

A limitation of this study is that it was a relatively small-scale pilot study. Owing to the lack of reference data to determine the appropriate study group size for demonstrating differences between tegoprazan and esomeprazole, we adhered to the typical sample size for pilot studies. This study design might have contributed to the inability to demonstrate differences in satisfaction or symptom improvement at week 4, 8 between the two groups. However, this study is significant as it is the first multicentre, prospective study to demonstrate the efficacy of tegoprazan in on-demand therapy, and provides key evidence that tegoprazan ensures a faster clinical improvement effect compared to PPIs. We anticipate that future large-scale studies with a larger sample will further substantiate the superiority of P-CAB in on-demand therapy.

In conclusion, tegoprazan is effective as on-demand therapy for GERD. Tegoprazan, when used as an on-demand regimen, improves patient symptoms more rapidly when compared to esomeprazole.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Vakil, N., van Zanten, S. V., Kahrilas, P., Dent, J. & Jones, R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 101, 1900–1920 (2006). quiz 1943.

Jung, H. K. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia: a systematic review. J. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 17, 14–27 (2011).

Jung, H. K. et al. 2020 Seoul Consensus on the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 27, 453–481 (2021).

Kang, S. J., Jung, H. K., Tae, C. H., Kim, S. Y. & Lee, K. J. On-demand versus continuous maintenance treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease with proton pump inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 28, 5–14 (2022).

Haastrup, P. F., Thompson, W., Søndergaard, J. & Jarbøl, D. E. Side effects of long-term proton pump inhibitor use: a review. Basic. Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 123, 114–121 (2018).

Sawaid, I. O. & Samson, A. O. Proton pump inhibitors and cancer risk: a comprehensive review of epidemiological and mechanistic evidence. J. Clin. Med. 13, 1970 (2024).

Poly, T. N. et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of gastric cancer: current evidence from epidemiological studies and critical appraisal. Cancers (Basel). 14, 3052 (2022).

Han, S. et al. Randomised clinical trial: safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of single and multiple oral doses of tegoprazan (CJ-12420), a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, in healthy male subjects. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 50, 751–759 (2019).

Fass, R. et al. Randomised clinical trial: efficacy and safety of on-demand vonoprazan versus placebo for non-erosive reflux disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 58, 1016–1027 (2023).

Hoshikawa, Y. et al. Efficacy of on-demand therapy using 20-mg vonoprazan for non-erosive reflux disease. Esophagus 16, 201–206 (2019).

Jenkins, H. et al. Randomised clinical trial: safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of repeated doses of TAK-438 (vonoprazan), a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, in healthy male subjects. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 41, 636–648 (2015).

Sunwoo, J. et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of DWP14012, a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, in healthy male subjects. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 48, 206–218 (2018).

Tsai, H. H. et al. Esomeprazole 20 mg on-demand is more acceptable to patients than continuous lansoprazole 15 mg in the long-term maintenance of endoscopy-negative gastro-oesophageal reflux patients: the COMMAND Study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 20, 657–665 (2004).

Lee, K. J. et al. Randomised phase 3 trial: tegoprazan, a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, vs. esomeprazole in patients with erosive oesophagitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 49, 864–872 (2019).

Thomson, A. B. Are the orally administered proton pump inhibitors equivalent? A comparison of lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2, 482–493 (2000).

Fock, K. M., Ang, T. L., Bee, L. C. & Lee, E. J. Proton pump inhibitors: do differences in pharmacokinetics translate into differences in clinical outcomes. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 47, 1–6 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by HK inno.N Corp, whereby HK inno.N provided financial support and the study drug.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: S.H.K., K.H.S., S.M.K. Data acquisition: S.H.K., H.S.M., J.K.S., S.M.K., K.B.K., S.W.L., Y.S.C., K.B.B., K.H.S. Data analysis and interpretation: S.H.K. Drafting of the manuscript: S.H.K. and S.M.K. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: H.S.M, J.K.S., K.B.K., S.W.L., Y.S.C., K.B.B., K.H.S. Statistical analysis: S.H.K. Obtained funding: S.M.K Study supervision: S.M.K, K.H.S. All authors approved the final version of the article, including the authorship list.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

This study was supported by HK inno.N Corp., Seoul, Republic of Korea, whereby HK inno.N sponsored the study and provided the study drug. The sponsor had no role in the study design, study conduct, data analysis, and interpretation of the data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, S.H., Moon, H.S., Sung, J.K. et al. Assessment of the efficacy of on-demand tegoprazan therapy in gastroesophageal reflux disease through a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 168 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84065-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84065-0