Abstract

Climate change-induced precipitation extremes are a pressing global concern. This study investigates the predictability of precipitation patterns and extremes across North Indian states from 1984 to 2023 using NASA’s Prediction of Worldwide Energy Resources (POWER) datasets and machine learning (ML) models. The current ML model builds on the relationship between rainfall and key climatic parameters such as dew point temperature and relative humidity, showing a strong positive correlation (CC = 0.4) significant at the 0.05 level. In simulating precipitation, Random Forest Classifier (RFC) achieved the highest accuracy (~ 83%) for Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, while Support Vector Classifier (SVC) performed best (79–83% accuracy) in other states. However, ML models exhibited approximately 5% lower skill in higher elevated stations as compared to lower ones, due to differing atmospheric mechanisms. For extreme precipitation events (10th and 95th percentiles of intensity), RFC consistently outperformed SVC across all states showing superior ability to distinguish extreme from non-extreme events (Area Under Curve ~ 0.90) and better model calibration (Brier Scores ~ 0.01). The developed ML models effectively simulated precipitation and extreme patterns, with RFC excelling at classifying extreme events. These findings can aid disaster preparedness and water resource management in regions with varied topography and complex terrain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extreme precipitation events, intensified by global warming, have become significant challenges for both society and the environment. These events, characterized by intense precipitation, can inflict severe damage on agriculture, ecosystems, and human communities1,2,3,4,5. As atmospheric moisture content rises due to climate change, these events are projected to become more frequent and intense. Observational data since the 1950s indicate a noticeable increase in the occurrence of heavy precipitation events in many regions, a trend expected to continue, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change6. The sixth assessment report (AR6) also underscores that local communities, particularly those with limited adaptive capacity, are disproportionately vulnerable to these impacts7.

The mechanisms associated with the extreme precipitation events during the monsoon season, mostly triggered by the interactions between westward-moving monsoon systems, eastward-moving mid-tropospheric westerly troughs, and the rugged Himalayan topography, have had devastating consequences in various parts of Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and Jammu & Kashmir. Notable incidents include the Kedarnath tragedy (2013)8,9 and Uttarakhand cloudburst (2022, 2017, 2012)10,11,12, Lahaul-Spiti (July 2021), Mandi (July 2015)13,14, Leh cloudburst (2015, 2010)15,16, and the Jammu & Kashmir floods (2015, Sonmarg, Pahalgam, Ganderbal and Baltal)16 and many more reported in detail in a study conducted by Dimri et al., (2017). These events, often caused by the interaction of multiple atmospheric dynamics, lead to excessive precipitation, casualties, and significant infrastructural damage.

In North India, extreme precipitation events result from complex dynamics involving both large-scale atmospheric influences and localized factors. The unique topography of North India, particularly the Himalayas, plays a crucial role in shaping the Indian monsoon17,18,19,20,21. The interplay between the mountainous terrain and atmospheric disturbances, coupled with cold air intrusion from northern latitudes, creates conditions conducive to extreme precipitation events, as seen in Jammu and Kashmir during January 2017 22. Western disturbances, embedded in the eastward-moving upper tropospheric Rossby wave train, contribute significantly to heavy precipitation in the Western Himalayas, especially during winter23,24,25. The high temperatures over the mountains and neighbouring areas contribute to the formation of low-pressure systems, which extend southward across the plains of South Asia, facilitating the northward progression of the monsoon26,27,28. The 2013 Uttarakhand disaster, which involved rapid monsoon progression and heavy precipitation, resulted from a combination of these large-scale circulations, orographic lifting, and intense convective activity29. These extreme precipitation events are known to exacerbate due to climate change with increased frequency and intensity16,30.

Traditional modeling approaches struggle to capture the complex interplay of factors shaping precipitation patterns, including climate change, topography, and atmospheric dynamics31,32,33. In response, integrating machine learning (ML) techniques has emerged as a promising avenue for understanding precipitation34,35,36,37 and extreme precipitation38,39,40,41 variability and enhancing forecasting accuracy leveraging large meteorological datasets and computational power to improve predictive capabilities amid climate change uncertainties34,35,36.

For India, a few literatures are available for extreme precipitation analysis30,42,43,44, however relatively fewer for extreme precipitation modelling using machine learning37,45,46. The limited availability of high-quality and comprehensive meteorological data in India and complexity of the regional topography and climate are also prominent contributing factor for limited number of research. A study by Ray et al. (2022) suggest that machine learning techniques, can effectively predict precipitation by correlating meteorological parameters with precipitation events47.

In light of aforesaid reasons, our study aims to explore key atmospheric variables affecting precipitation patterns and extreme events in North India and studies link between these variables and precipitation intensity across regions. This analysis provides a solid foundation for understanding the complex interplay between these variables and precipitation patterns.

Building upon this foundation, the study employs machine learning models to tackle the challenge of classifying precipitation events at different thresholds. These models are trained and evaluated on different data splits, with a primary objective of accurately determining whether precipitation will occur or not within a given timeframe and geographic area. The performance of these models is meticulously assessed using accuracy as a metric for decision making, ensuring model’s reliability and robustness. Recognizing the significance of extreme precipitation events, the study takes a step further by defining thresholds based on the 10th and 95th percentiles of precipitation intensity. These thresholds serve as benchmarks for identifying extreme event occurrences, both in terms of low and high precipitation levels. The machine learning models are then evaluated on their ability to accurately classify events falling within these extreme percentile ranges. Ultimately, the goal is to harness ML to improve the accuracy and reliability of precipitation forecasts, helping policymakers and communities prepare for and mitigate the impact of extreme weather events in the context of climate change.

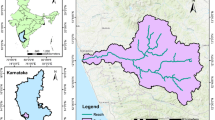

Study area

Encompassing a vast region in North India, this study area covers seven states: Himachal Pradesh (HP), Jammu and Kashmir (JK), Punjab and Haryana (PH) (considered together), Rajasthan (RJ), Uttarakhand (UK), and Uttar Pradesh (UP) (Fig. 1). The dramatic elevation range stretches from a low point of 60 m in Uttar Pradesh to a staggering 8,611 meters at K2 Peak in Jammu and Kashmir. This translates to significant temperature variations across the region. The plains experience scorching summers with highs reaching 45 °C, particularly in the Rajasthan’s Thar Desert, while winters can be mild with lows around 0 °C. In contrast, the hilly regions offer cooler summers with highs of 25 °C, but winters can be harsh with temperatures dipping as low as -30 °C in Jammu and Kashmir48,49.

Each state within this diverse landscape faces distinct environmental challenges50. The Himalayan states like Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and Jammu and Kashmir grapple with issues like forest fires, biodiversity loss, glacial retreat leading to water scarcity, and soil erosion. Meanwhile, the plains states of Uttar Pradesh, Punjab & Haryana, and Rajasthan battle water scarcity, soil degradation, and air pollution. Additionally, all states face challenges related to the impact of climate change on agriculture51,52. Understanding this interplay between natural processes and human activities across this vast region with its varying elevations and temperatures is crucial for developing effective management strategies and sustainable development practices30,51.

Climatic condition and regional characteristics of precipitation in North India

North India’s climate is diverse due to its varied topography, which includes the Himalayas, the Thar Desert, and the Indo-Gangetic Plain49,53,54,55. The Himalayan region, encompassing Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Jammu & Kashmir, and Ladakh, experiences an alpine and subtropical climate with cold winters, mild summers, and heavy snowfall in higher altitudes56,57. The Indo-Gangetic Plain, which covers states like Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh, has a subtropical monsoon climate characterized by hot summers, cold winters, and a distinct monsoon season from June to September53,58,59. The Thar Desert in Rajasthan features an arid climate with extreme temperatures and scanty rainfall60,61. These regions are influenced by the monsoon winds that bring significant rainfall to the plains and southern slopes of the Himalayas while creating a rain shadow effect in the desert areas54,62.

Seasonal variations play a significant role in shaping the climate across North India. Summers (April to June) are marked by extreme heat, particularly in the plains and desert areas, with temperatures often exceeding 45 °C48. The southwest monsoon season (June to September) brings heavy rains essential for agriculture but also poses risks of flooding and landslides in the Himalayan region63.

Autumn (October to November) is a transition period with receding monsoon rains and cooling temperatures. Winters (December to February) are cold, with western disturbances bringing rain and occasional snowfall to the plains and mountains. Spring (March to April) sees gradual warming and blooming flowers, marking the end of winter and the onset of the hot season. The Himalayas significantly influence these patterns by acting as a barrier to cold winds and affecting monsoon rainfall distribution48.

The precipitation characteristics across the North Indian states exhibit significant variations, as evident from the analysis of annual maximum precipitation (Fig. 2), and threshold values corresponding to the 10th and 95th percentiles (Table 1).

Uttarakhand (UK) experienced the highest maximum precipitation of 158.40 mm, followed by Punjab (PH) with 136.26 mm and Uttar Pradesh (UP) with 142.43 mm, representing regions with relatively higher precipitation levels. In contrast, Rajasthan (RJ) and Jammu and Kashmir (JK) recorded lower maximum precipitation values of 91.75 mm and 100.79 mm respectively, indicating drier conditions. Uttarakhand exhibited the highest standard deviation of 8.30 mm, suggesting greater variability in precipitation values around the maximum, while Rajasthan had the lowest standard deviation of 4.77 mm, indicating a more consistent pattern.

The 10th percentile thresholds, representing low precipitation events, ranged from 0.03 mm in Himachal Pradesh (HP), Jammu and Kashmir (JK), and Rajasthan (RJ) to 0.05 mm in Punjab (PH). The 95th percentile thresholds, indicating extreme high precipitation events, varied from 17.71 mm in Jammu and Kashmir to 27.58 mm in Uttarakhand. Jammu and Kashmir experienced the highest number of events (7104) below the 10th percentile threshold, while Himachal Pradesh recorded the highest (363) above the 95th percentile.

Overall, regional disparities exist, with higher maximum precipitation in Uttarakhand, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh indicating wetter conditions, contrasted by drier conditions in Rajasthan and Jammu and Kashmir. The state of Uttarakhand exhibited greater precipitation variability, while Rajasthan had a more consistent pattern for precipitation during the study period. The state of Jammu and Kashmir had the highest frequency of low precipitation events, while Himachal Pradesh experienced more extreme high precipitation events. Meanwhile, the region-specific analysis and modeling approaches are crucial to capture the unique precipitation dynamics across the diverse North Indian states.

Results

State specific inter-variable analysis

Understanding the intricate relationships between atmospheric variables is crucial for accurate classification of precipitation events39. In this section these intricacies are explored by examining state-specific inter-variable interactions. For each state’s capital included in the study, correlation matrices were generated (Fig. 3). These matrices provide a valuable tool to explore the strength and direction of linear associations between the chosen atmospheric variables (temperature, humidity, pressure, etc.). By analyzing these correlations, we aim to identify recurring patterns, potential dependencies between variables within each state, and any instances of multicollinearity.

Examining these state-specific relationships allows for a more nuanced understanding of how atmospheric variables interact and influence precipitation patterns across diverse geographical regions within North India64.

Across all states, a consistent theme emerges: Dew Point Temperature, Surface Pressure and Relative Humidity tend to be the strongest allies of precipitation. Strong Positive correlations of Dew Point Temperature, Surface Pressure (~ 0.4) and Strong negative correlations (~ -0.3) of Relative Humidity highlights their potential role as significant contributors to increased precipitation, when compared to all variables considered in this study. For states like HP and UK, precipitation exhibit positive correlations (0.013, 0.04) with temperature, while PH, JK, and UP show weaker negative (-0.0028 to -0.04) associations, pointing towards a more precise observation, while considering only temperature as a variable affecting precipitation over the state.

In almost all states, solar irradiance and surface pressure acts as a counterpoint to precipitation, exhibiting negative correlations ranging from − 0.18 in PH (Solar irradiance) to a more pronounced − 0.3 in HP, RJ, UK and UP (Surface pressure). The impact of wind on precipitation varies across states. While RJ, UP and JK show modest positive correlations (0.04, 0.11 and 0.24), other states like HP, PH and UK exhibit weakly negative associations (-0.072, -0.054 and 0.037) respectively with wind (Fig. 3).

Overall precipitation patterns across the study region are influenced by a complex interplay of various atmospheric factors, both directly and indirectly. In the direct category, elevated levels of dew point temperature, relative humidity and surface pressure emerge as significant contributors to increased precipitation in the study locations. These states consistently exhibit strong correlations between Dew Point Temperature, Surface Pressure, Relative Humidity, and precipitation, underscoring the direct impact of these meteorological variables on precipitation. Additionally, surface pressure and solar irradiance displays a notable indirect relationship, with lower level of the events associated with higher precipitation events across the study location, however correlation with surface pressure was only statistically significant at significance level of 0.05. Conversely, temperature and wind demonstrate a varied impact, with both positive and negative correlations observed in different states, indicating that warmer and windier conditions may contribute to precipitation in some regions while having the opposite effect in others (Fig. 3).

ML model performance in precipitation classification

Taking these variables under consideration, four machine learning models, namely – Support Vector Classifier (SVC), Random Forest Classifier (RFC), XGBoost, and K Nearest Neighbors (KNN) – were developed to analyze precipitation and its extreme patterns over the study locations. The models were trained over the pre-processed dataset to achieve the highest possible accuracies. The developed model was trained to predict not only simple precipitation events, but extreme precipitation events at different threshold levels also. The developed model was trained and tested at different data split ratios and were evaluated based on their accuracy for classifying precipitation events across all states. Figure 4. illustrates the accuracy achieved by various machine learning algorithms across different states for different train test split ratios.

Himachal Pradesh

The analysis revealed that SVC consistently achieved the highest accuracy scores across all train-test split ratios in Himachal Pradesh, ranging from 83.35% to 83.50%. This suggests the effectiveness of SVC in capturing the complex interplay between various atmospheric variables and precipitation patterns in this state. The mountainous terrain and diverse climate of Himachal Pradesh necessitate a robust model capable of handling intricate relationships. RFC followed closely with accuracy scores ranging from 82.84 to 82.94%, demonstrating strong and reliable performance. This indicates the suitability of both SVC and RFC for classifying precipitation in Himachal Pradesh. XGBoost maintained competitive accuracy (82.28−82.75%), while KNN also achieved a reliable score (81.62−81.74%) (Fig. 4). Here, the consistent high accuracy of SVC and RFC suggests their ability to effectively model precipitation patterns in Himachal Pradesh’s diverse topography and climatic zones.

Jammu and Kashmir

Similar to Himachal Pradesh, SVC emerged as the most effective algorithm for precipitation classification in Jammu and Kashmir (Fig. 4). The average accuracy across all split ratios for SVC was 79.79%, closely followed by RFC with an average accuracy of 79.61%. This indicates the suitability of both algorithms for capturing precipitation patterns in this state characterized by the Himalayas and Kashmir Valley with its unique weather systems. XGBoost and KNN achieved average accuracies of 78.69% and 77.64%, respectively.

The effectiveness of SVC and RFC in Jammu and Kashmir underscores their ability to handle the complex interactions between atmospheric variables in a region with significant topographic variations.

Punjab and Haryana

The analysis revealed SVC as the most effective algorithm across all split ratios for classifying precipitation in Punjab and Haryana (Fig. 4). The average accuracy for SVC was 82.06%, followed closely by XGBoost with an average accuracy of 81.77%. RFC and KNN achieved slightly lower average accuracies of 80.65% and 81.03%, respectively. Interestingly, SVC exhibited superior performance, particularly at higher split ratios, showcasing its robustness in handling varying data distributions. This highlights its suitability for capturing precipitation patterns influenced by diverse factors such as the proximity to the Himalayas and the Indus River basin. The strong performance of SVC in Punjab and Haryana suggests its effectiveness in modeling precipitation patterns in the region’s predominantly flat plains.

Rajasthan

In contrast to other states, RFC emerged as the top performer for precipitation classification in Rajasthan. The consistently high accuracy scores achieved by RFC, ranging from 83.55% to 83.71%, indicate its effectiveness in capturing precipitation patterns in this arid state. SVC displayed competitive performance with accuracy scores ranging from 82.34% to 82.79%. XGBoost also showcased consistent performance with accuracy scores between 82.78% and 83.22%. While KNN achieved lower scores (82.00−82.06%), it still offers reasonable predictive capabilities.

Uttarakhand

Similar to Himachal Pradesh, SVC emerged as the leader for precipitation classification in Uttarakhand. Its accuracy scores ranged from a high of 84.47% to a low of 84.16% across different split ratios. This consistency suggests SVC’s effectiveness in capturing the intricate relationships between atmospheric variables and precipitation patterns in this state characterized by the Himalayan foothills and diverse microclimates. RFC followed closely with accuracy scores ranging from 83.84 to 83.96%, demonstrating strong performance. XGBoost displayed competitive accuracy (83.33−83.76%), while KNN achieved moderate scores (82.93−83.25%) compared to other ML models.

Uttar Pradesh

In Uttar Pradesh, the analysis revealed RFC as the dominant algorithm for precipitation classification. It achieved the highest accuracy scores across all splits, ranging from 84.70% to 85.05%. XGBoost followed closely with accuracy scores ranging from 83.93% to 84.50%. SVC maintained competitive scores (83.78%−84.16%). KNN achieved moderate accuracy (83.57%−83.73%). The dominance of RFC in Uttar Pradesh, the most populous state in India, can be attributed to its ability to effectively model precipitation patterns influenced by diverse factors such as the Gangetic Plain’s topography and proximity to the Himalayas. The strong performance of both RFC and XGBoost suggests promising avenues for further exploration and potential implementation in operational forecasting systems.

Overall, SVM and RF emerged as strong contenders in our analysis of mapping precipitation patterns across various states in North India (Fig. 5). Notably, SVM consistently outperformed RF in the majority of states, showcasing its effectiveness in accurately classifying precipitation patterns. Interestingly, the RF model exhibited superior performance in Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh state for precipitation event classification when compared to all the models under consideration. The RF model achieved the highest accuracy scores among all algorithms tested. This observation underscores the nuanced nature of regional climatic patterns and highlights RF’s capability to excel in certain geographical contexts. Upon aggregating the results from multiple iterations and train-test split ratios, we constructed line plot (Fig. 5.) for each state individually, providing a comprehensive overview of algorithm performance.

These plots affirmed the dominance of SVM across most states, but both SVM and RF demonstrated comparable performance, indicating a close competition between the two algorithms. Additionally, the study revealed an inverse correlation between elevation and the performance of machine learning algorithms in simulating precipitation and its extremes over the capital cities in North Indian states. Specifically, in regions with lower elevations, the models exhibited higher skill (accuracy) in simulating precipitation, while in areas with higher elevations, the model skill was relatively lower, with a skill difference of approximately 5%. This observation highlights the influence of topographic features and associated meteorological complexities on the models’ ability to accurately capture precipitation patterns.

Evaluation of model performance for extreme precipitation

Building on our previous model evaluation, which demonstrated competitive performance between RFC and SVC models for general precipitation patterns across most states, we ought to specifically evaluate their effectiveness in classifying extreme precipitation events. For this we implemented a two-pronged evaluation for this purpose. First, both models were evaluated using all initial variables (Fig. 6) and then only for statistically significant variables (Fig. 7) across different states. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were generated for each scenario to visualize model discrimination between extreme events below 10th and above 95th percentiles (Figs. 6 and 7). While AUC of an ROC curve provides a good overview of model performance, it’s valuable to consider additional metrics for a more comprehensive evaluation and robustness check of the build models. Here, we considered Brier Score in order to assesses the overall calibration of the model’s classification probabilities with respect to actual outcomes (Fig. 8).

Illustration of ROC curves when all variables are taken into consideration. The illustration showcasing AUC achieved for the 10th percentiles (Class 1) and 95th percentiles (Class 2) in each state. The figures are labelled according to the state initials followed by the model’s name. For instance, HP-RF denotes the Random Forest Model applied to Himachal Pradesh.

Illustration of ROC curves when statistically significant variables are taken into consideration. The illustration showcasing AUC achieved for the 10th percentiles (Class 1) and 95th percentiles (Class 2) in each state. The figures are labelled according to the state initials followed by the model’s name. For instance, HP-RF denotes the Random Forest Model applied to Himachal Pradesh.

By comparing ROC values and Brier Scores across models and variable selection approaches, we aimed to identify the most effective model for extreme precipitation classification.

-

Overall Performance: Both models (RFC and SVC) exhibit good skill in classifying extreme precipitation events, with AUC values generally exceeding 0.85 across states and scenarios (Figs. 6 and 7). This indicates a strong ability to discriminate between extreme and non-extreme events.

-

Model Comparison: While there are some variations, the performance of RFC and SVM models is often comparable, with neither model consistently outperforming the other across all states and scenarios.

-

Impact of Variable Selection: Focusing on statistically significant variables sometimes results in slightly improved AUC values for the SVM model (e.g., state JK at the 95th percentile threshold) (Fig. 7). However, the differences are generally small, suggesting that the additional variables included in the “all variables” scenario might not significantly impact model performance for extreme event classification.

-

State-Specific Variations: There is some variation in model performance across states for the period 1984 to 2023. States like RJ and UP show consistently high AUC values (> 0.90) for both models in both scenarios, indicating exceptional skill in classifying extreme events. Conversely, states like HP and PH show slightly lower but still good performance (AUC around 0.87–0.90). This might be due to topographic differences in extreme precipitation patterns or require further investigation into specific factors or regional dynamics influencing precipitation in those states.

-

Threshold Dependence: As expected, AUC values are generally higher for the 95th percentile threshold compared to the 10th percentile threshold. This is because the 95th percentile represents a more extreme precipitation event, which might be easier for the models to predict accurately.

The presented Brier Scores provide additional insights into the performance of Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) models for classifying extreme precipitation events across different states. Brier Score measures the mean squared difference between the predicted probability of an extreme event and the actual outcome (0 or 1). A lower Brier Scores indicate better model performance, signifying classification results closer to actual occurrences (Fig. 8).

-

Overall Brier Score: The Brier Scores range from approximately 0.07 to 0.12 across states and models. These are generally considered good scores, indicating the models are providing reasonably accurate probability estimates for extreme precipitation events.

-

Model Comparison: Similar to the AUC results, there are no significant differences between RF and SVM models in terms of Brier Scores for most states. Both models achieve comparable performance.

-

Impact of Variable Selection: Focusing on statistically significant variables (often including humidity and surface pressure) sometimes leads to slightly higher Brier Scores (worse performance) compared to inclusion of all variables. This suggests that while some variables might not be statistically significant, they could still contribute to the model’s ability to calibrate its classification result.

-

State-Specific Variations: Brier Scores also show some variation across states. States like RJ and UP consistently have lower Brier Scores (better performance) compared to states like HP and JK. This aligns with the observations from AUC values, suggesting these states might have more predictable extreme precipitation patterns or benefit from the additional information captured by all initial variables.

Discussion

Extreme precipitation classification using supervised machine learning involves leveraging advanced algorithms to identify and categorize precipitation events based on their intensity and impact. This approach is crucial for improving the prediction and management of extreme weather events, which are becoming more frequent due to climate change. In agreement with previous research, our results demonstrate the efficacy of SVM and RF algorithms in precipitation classification.

Our results on RF’s effectiveness in simulating precipitation extremes in North India are consistent with international studies. Research across the United States39 and China65 has similarly demonstrated RF’s high accuracy in extreme event classification and forecasting. This global consistency suggests RF possesses inherent advantages for this specific task, possibly due to its capacity to handle high dimensionality and non-linearity efficiently39,65,66,67.

The superior performance of SVM across most states aligns with Nayak’s68and vijayakumar’s study69 and, who reported its effectiveness in short-term predictions and weather pattern identification. Similarly, RF’s exceptional accuracy in Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh corroborates39 findings on RF’s suitability for regions with distinct seasonal patterns. These consistencies suggest that both algorithms possess inherent advantages in handling the complex, non-linear relationships characteristic of meteorological data.

However, our research diverges from some previous studies in terms of relative algorithm performance. While Shin70found RF superior in classifying precipitation types using dual-polarization radar and thermodynamic data, our results indicate SVM superiority in comparison to RF across most of the states, although RF model was concluded as superior model among the two as it depicted low briers score for overall study area. This alignment and discrepancy highlights the importance of considering regional variations and specific data types in algorithm selection for precipitation classification.

The findings partially align with a study conducted in the Pangani River Basin, Northern Tanzania, which similarly identified Random Forest as a top-performing algorithm for extreme rainfall classification. However, while our study found Support Vector Machines (SVM) to outperform Random Forest in most North Indian states, the Tanzanian study reported XGBoost as another top performer, highlighting potential regional variations in algorithm efficacy71. Other similar case is with the study over Western Ghats region in India72 that showcases the effectiveness of XGBoost and RF models in multi-model ensembles for capturing the behaviour of climate change on precipitation patterns and the success of the improved K-Nearest Neighbor model in simulating such events in New Delhi, India73.

Our study’s high accuracy rates, particularly in extreme rainfall classifications, concur with Zhang’ research74 who reported true positive rates around 99%. This consistency across diverse geographical contexts underscores the robustness of machine learning approaches in extreme precipitation classification. Furthermore, our findings align with the growing trend of machine learning applications in meteorology, as noted by Abed & Coppola75and Hammami & Elasmi76, reinforcing the potential of these techniques for improving extreme weather event prediction and climate adaptation strategies.

A novel aspect of our study is the identification of an inverse correlation between elevation and model performance. Models achieved 84% accuracy in lower elevation regions like Uttar Pradesh (123 m), compared to 79% in higher elevation areas such as Jammu and Kashmir (average 1585 m). This 5% discrepancy, attributed to complex orographic effects and potential data scarcity in remote, high-elevation areas, introduces a new dimension to the discourse on extreme precipitation classification. While this finding lacks direct precedent in the literature, it aligns with broader research emphasizing the impact of topographical features on precipitation patterns72,73.

Overall, our study largely aligns with existing literature on the efficacy of machine learning in extreme precipitation classification, it also reveals important distinctions in regional algorithm performance and introduces novel considerations regarding elevation’s impact on model accuracy. These findings underscore the need for tailored approaches in different geographical contexts and open new avenues for future research, including the exploration of multi-model ensembles and the integration of temporal modeling techniques such as Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTMs) to capture sequential patterns in precipitation data.

Conclusion

In this work, a comprehensive study was conducted to investigate the intricate interplay between atmospheric variables and extreme precipitation events across the seven states in North India. The study leverages combination of data from NASA’s POWER project spanning from 1984 to 2023 and employed four machine learning models (Support Vector Classifier (SVC), Random Forest Classifier (RFC), XGBoost, and K Nearest Neighbors (KNN)) for precipitation classification, specifically for observed extreme event.

The analysis revealed insightful correlations between key predictor variables and extreme precipitation intensity for each region. Dew Point Temperature and Relative Humidity exhibited strong positive correlations (~ 0.4) with precipitation across all states, while Temperature exhibited regional variations with positive correlations in Himachal Pradesh, Punjab and Haryana, and Uttarakhand (~ 0.2), and weaker negative associations in Jammu and Kashmir, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh (− 0.1 to − 0.2). Solar irradiance and Surface Pressure often depicts counterpoints to precipitation, with negative correlations ranging from − 0.18 to − 0.3. The significance of these variables was taken into account while performing probabilistic classification in case of extreme precipitation pattern detection. The predictive classification aspect, employed machine learning algorithms across all states which depicted competitive performance among algorithms.

SVC and RFC emerged as powerful tools for precipitation classification in a changing climate, with SVC dominating in Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Uttarakhand, and Punjab and Haryana, while RFC excelled in Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. The models exhibited higher skill in simulating precipitation over lower elevation regions compared to higher elevation areas, with a skill difference of around 5%, potentially due to the influence of topographic complexity on meteorological phenomena. Furthermore, the analysis of extreme precipitation events revealed that Random Forest models consistently outperformed Support Vector Machines, achieving higher Area Under the Curve (AUC) values (~ 0.90), and lower Brier Scores (~ 0.01), across all states and precipitation thresholds. Despite the promising results, the study acknowledges limitations such as reliance on reanalysis data, limited atmospheric variables, coarse spatial and temporal resolutions and significant effects of climate changes as anthropogenic emission, human induced changes, that were not considered in the present study.

The study’s success with Random Forest models for simulating precipitation extremes among all the models considered in this study, paves the way for further advancements. Future research should explore more advance algorithms like LSTMs and ensemble learning approaches, as well data augmentation strategies and include climate changes factors into consideration. Integrating high-resolution data, climate change projections, and atmospheric processes into the models can enhance their accuracy and robustness. Ultimately, these advancements should be translated into practical tools for real-time flood and drought forecasting, optimizing agricultural practices, and informing adaptation strategies. By considering both atmospheric processes and anthropogenic influences, we can develop comprehensive and holistic models for understanding and both classification and prediction of precipitation extremes, leading to a more sustainable future in the face of climate change.

Data

The study utilized data from NASA’s Prediction of Worldwide Energy Resources (POWER) project spanning from 1984 to 2023 77 with a daily temporal resolution. The data collection process was centred around obtaining meteorological observations from the capital cities of each state in North India, strategically chosen as representative locations to assess and characterize the atmospheric conditions prevalent across their respective states. This approach aimed to capture the regional variations in climate and weather patterns that influence precipitation dynamics in the region. The study encompassed a comprehensive set of seven atmospheric variables, which were meticulously recorded and analyzed. The atmospheric variables were maximum temperature, relative humidity, surface pressure, wind speed, dew point temperature, precipitation and solar irradiance.

The POWER project provides Meteorological data from Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, version 2 (MERRA-2)77 and Solar Irradiance data from Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System Project (CERES). Thus the data was a combination of MERRA-2 78,79,80,81,82 and CERES SYN83,84,85,86 and has been widely used by researchers for various climate and atmospheric studies. The comprehensive coverage of atmospheric and climate variables, alongside its high spatial and temporal resolution, is underscored by its assimilation of a wide range of satellite observations and other data sources, making it a valuable asset for climate and atmospheric research. MERRA-2 served a grid resolution of 0.5*0.625 degrees and demonstrates advancements in addressing known deficiencies, such as reducing spurious trends and jumps associated with changes in the observing system, as well as mitigating biases and imbalances in aspects of the water cycle77. CERES-SYN served a grid resolution of 1*1 degrees. This product provides accurate satellite-retrieved estimates of Earth’s radiation budget components, including downwelling longwave radiation at the surface and other atmospheric levels from 2000 to the present. It utilizes radiation transfer model along with improved cloud property retrievals and consistent temperature/humidity data to estimate radiative fluxes more accurately. As a representative global satellite product covering various timescales, CERES-SYN serves as a valuable data source for evaluating reanalysis radiation estimates over regions lacking sufficient ground observations.

Methodology

The dataset utilized in this study, has been employed for evaluation of hydrological performance of precipitation products different locations and over Basins87,88, for analysis of the diurnal cycle of summer precipitation and associated land-atmosphere interactions89, drought estimations90 and other hydrometeorological application91,92,93.

The authors used standard setting while performing model simulations to ensure the comparability and replicability of the obtained results (Table 2). We performed feature engineering over the dataset, which include steps as data cleaning, normalization, scaling dropping of any null values present in the dataset.

After the preprocessing, our primary step was to find the intricate relationships between various atmospheric variables. For this, Pearson standard correlations were performed and analyzed94,95,96,97. The correlation coefficient is a statistical measure often used in studies to represent an association between variables or to evaluate the agreement between two methods. Here, we used it to determine the association between meteorological variables and the target variable ‘precipitation’. The most common measure of correlation can take on values from − 1.0 to 1.0. A value of 1.0 indicates a perfect positive correlation, − 1.0 indicates a perfect negative correlation, and 0.0 indicates no correlation. Generally, Pearson’s correlation between − 0.5 and 0.5 indicates a weak or no association between two variables, while a correlation between 0.5 and 1.0 indicates a strong positive association. In accordance to our data, a value of 0.304 was obtained to be statistically significant at 0.05 significance level. This provided an added insight into the most and least influential parameters affecting precipitation patterns at the selected location.

The next crucial step was the selection and application of machine learning (ML) models to the dataset for precipitation event classification based on atmospheric variables. We employed well-established algorithms like Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), XGBoost (XGB), and k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN). These models are specifically choosen as they models have consistently demonstrated strong performance in various classification tasks across domains and can capture complex, nonlinear relationships between input features and target variables, which is often the case with environmental and meteorological data. Models like RF and XGBoost are robust to noise, handle high-dimensional feature spaces effectively, and provide feature importance analysis for interpretability102,103,104,105,106,107.

By including tree-based (RF, XGBoost), kernel-based (SVM), and instance-based (kNN) models, we aimed to leverage diverse modeling approaches and capture different perspectives on the underlying relationships between atmospheric variables and precipitation events. Additionally, Table 2 presents an overview of these model working, workflow the model follows and some specific setting for simulations.

The authors employed a comprehensive approach to train models for predicting extreme precipitation events across the North Indian region. The process began with careful consideration of data categorization into two distinct classes to focus specifically on extreme events. Class 1 represented low precipitation or drought conditions (≤ 10th percentile), Class 2 represented extreme high precipitation (≥ 95th percentile), This classification enabled the model to concentrate on both low and high extremes, allowing for a more accurate understanding of the patterns associated with extreme precipitation.

Data splitting strategies was the next step followed after fixing the data classes. Multiple data split ratios were systematically tested to find the most suitable one for balancing training data sufficiency and model generalization. These split ratios included 80 − 20 (80% training, 20% testing), 70 − 30, 60 − 40, and 50–50 splits. The thorough testing of these splits ensured that the selected model could effectively generalize from the training data to unseen testing data, resulting in more reliable predictions.

Model training involved a rigorous process of multiple iterations to optimize performance. Each machine learning model underwent 25 to 30 iterations, with a seed number or random state of 42 used to ensure reproducibility of results. This iterative approach helped fine-tune the models, ensuring better accuracy and efficiency in predicting extreme precipitation events. The combination of well-structured data splits, classification schemes, and iterative training led to the development of robust models capable of effectively identifying and predicting extreme precipitation events in the North Indian region.

For evaluating our models, we used several metrics as accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, recall, F1-score, and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) and Briers Score. Each metric provides different insights into the model’s performance94,96,108,109,110 and are depicted with their mathematical formulas and definition in Table 3. The calculations are done on the basis of confusion matrix obtained after each iteration. A confusion matrix is a tabular representation that summarizes the performance of a classification model by comparing the predicted class labels with the true class labels (Fig. 9). It provides a comprehensive overview of the model’s accuracy, as well as its tendencies to make different types of errors, such as false positives and false negatives. The rows of the confusion matrix represent the true classes, while the columns represent the predicted classes, and the values in each cell indicate the number of instances that fall into each combination of true and predicted classes. However, we emphasized the selection of ‘accuracy’ as a parameter for forming comparison.

In order to thoroughly evaluate the performance of each algorithm, with a particular emphasis on their ability to accurately capture extreme precipitation patterns over the North Indian States, we employed a 70:30 train-test split for our data. This specific split ratio was chosen based on established practices in the literature, which suggest that it yields optimal results111,112 and also on the comparative performance observed among all splits at the time of accuracy evaluation in the previous segment. To assess model performance across different precipitation intensity levels, we generated Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves using the 10th and 95th percentile thresholds. These curves not only allowed us to assess sensitivity and specificity but also provided a comprehensive understanding of the Area Under the Curve (AUC), which serves as a valuable metric for quantifying the overall performance of each algorithm in distinguishing between positive and negative precipitation events. The AUC offers a nuanced perspective on the discriminatory power of the models, aiding in the identification of the most adept algorithm for capturing extreme precipitation occurrences in the North Indian region.

In addition to AUC, we also analysed Brier’s Score (Table 3). The Brier score provides a quantitative measure of the accuracy and calibration of probabilistic predictions108,113. It is widely used in various fields, including weather forecasting, risk assessment, and machine learning, to evaluate and compare the performance of models that generate probability predictions. A lower Brier Scores indicate better model performance, signifying classification results closer to actual occurrences.

Data availability

All the data utilized in this study are openly accessible and can be obtained by contacting the first author, Aayushi Tandon, via email at tdn2408aayushi@gmail.com, or directly from the source: NASA’s POWER Data Access Viewer at https://power.larc.nasa.gov.

References

Bhattacharyya, S., Sreekesh, S. & King, A. Characteristics of extreme rainfall in different gridded datasets over India during 1983–2015. Atmos. Res. 267, 105930 (2022).

Fowler, H. J. et al. Anthropogenic intensification of short-duration rainfall extremes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 107–122 (2021).

Mishra, V., Aadhar, S. & Mahto, S. S. Anthropogenic warming and intraseasonal summer monsoon variability amplify the risk of future flash droughts in India. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 4, 1–10 (2021).

Suman, M. & Maity, R. Southward shift of precipitation extremes over south Asia: Evidences from CORDEX data. Sci. Rep. 10, 6452 (2020).

Mukherjee, S., Aadhar, S., Stone, D. & Mishra, V. Increase in extreme precipitation events under anthropogenic warming in India. Weather Clim. Extremes. 20, 45–53 (2018).

Annex IX: Contributors to the IPCC Working Group I Sixth Assessment Report. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2267–2286 (eds Masson-Delmotte, V.) (Cambridge University Press, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.001

Pörtner, H. O. et al. IPCC, 2022: Summary for policymakers. in (eds. Pörtner, H. O. et al.) 3–33 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, US, 2022).

Sikka, D. R., Ray, K., Chakravarthy, K., Bhan, S. C. & Tyagi, A. Heavy rainfall in the Kedarnath valley of Uttarakhand during the advancing monsoon phase in June 2013. Curr. Sci. 109, 353–361 (2015).

Anoop Kumar, M. & J Srinivasan. Did a cloud burst occur in Kedarnath during 16 and 17 June 2013 (2013).

Rawat, K. S., Sahu, S. R., Singh, S. K. & Mishra, A. K. Cloudburst analysis in the Nainital district, Himalayan region, 2021. Discov Water. 2, 12 (2022).

Singh, B., Thapliyal, R. & IMD, M. Cloudburst events observed over Uttarakhand during monsoon season 2017 and their analysis. MAUSAM 73, 91–104 (2022).

Chevuturi, A. & Dimri, A. P. Investigation of Uttarakhand (India) disaster-2013 using weather research and forecasting model. Nat. Hazards 82, 1703–1726 (2016).

DNA. Cloudburst in Himachal Pradesh’s Mandi district kills 5 (2015). https://www.dnaindia.com/india/report-cloudburst-in-himachal-pradesh-s-mandi-district-kills-5-2112258

TOI. Himachal Pradesh cloudburst: 178 stranded people rescued from Lahaul-Spiti - India Today. (2021). https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/himachal-pradesh-cloudburst-178-stranded-people-rescued-from-lahaul-spiti-1835222-2021-07-31

Bhan, S., Devrani, A. & Sinha, V. An analysis of monthly rainfall and the meteorological conditions associated with cloudburst over the dry region of Leh (Ladakh), India. Mausam 66578540, 107–122 (2015).

Dimri, A. P. et al. Cloudbursts in Indian Himalayas: A review. Earth Sci. Rev. 168, 1–23 (2017).

Yadav, M., Dimri, A. P., Mal, S. & Maharana, P. Elevation-dependent precipitation in the Indian Himalayan region. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 155, 815–828 (2024).

Adhikari, P. & Mejia, J. F. Influence of aerosols on clouds, precipitation and freezing level height over the foothills of the Himalayas during the Indian summer monsoon. Clim. Dyn. 57, 395–413 (2021).

Mal, S. et al. Determining the quasi monsoon front in the Indian Himalayas. Quat. Int. 599–600, 4–14 (2021).

Rangwala, I., Palazzi, E. & Miller, J. R. Projected climate change in the Himalayas during the twenty-first century. in Himalayan Weather and Climate and Their Impact on the Environment (eds Dimri, A. P., Bookhagen, B., Stoffel, M. & Yasunari, T.) 51–71 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29684-1_4.

Acosta, R. P. & Huber, M. Competing topographic mechanisms for the summer indo-Asian monsoon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL085112 (2020).

Para, J. A. et al. Large-scale dynamics of western disturbances caused extreme precipitation on 24–27 January 2017 over Jammu and Kashmir, India. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 6, 99–107 (2020).

Aggarwal, D., Chakraborty, R. & Attada, R. Investigating bi-decadal precipitation changes over the northwest Himalayas during the pre-monsoon: role of pacific decadal oscillations. Clim. Dyn. 62, 1203–1218 (2024).

Hunt, K. M. R., Turner, A. G. & Schiemann, R. K. H. How interactions between tropical depressions and western disturbances affect heavy precipitation in South Asia. Mon. Weather Rev. 149, 1801–1825 (2021).

Kumar, P. V., Naidu, C. V. & Prasanna, K. Recent unprecedented weakening of Indian summer monsoon in warming environment. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 140, 467–486 (2020).

Singh, R., Jaiswal, N. & Kishtawal, C. M. Rising surface pressure over Tibetan Plateau strengthens Indian summer monsoon rainfall over northwestern India. Sci. Rep. 12, 8621 (2022).

Gupta, A. K., Prakasam, M., Dutt, S., Clift, P. D. & Yadav, R. R. Evolution and development of the Indian Monsoon. in Geodynamics of the Indian Plate: Evolutionary Perspectives (eds Gupta, N. & Tandon, S. K.) 499–535 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15989-4_14 (2020).

Hahn, D. G. & Manabe, S. The role of mountains in the south Asian monsoon circulation. J. Atmos. Sci. 32, 1515–1541 (1975).

Anu Xavier, M. G., Manoj & Mohankumar, K. On the dynamics of an extreme rainfall event in northern India in 2013. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 127, 30 (2018).

Pattnayak, K. C., Awasthi, A., Sharma, K. & Pattnayak, B. B. Fate of rainfall over the North Indian states in the 1.5 and 2 °C warming scenarios. Earth Space Sci. 10, e2022EA002671 (2023).

Alizadeh, O. Advances and challenges in climate modeling. Clim. Change 170, 18 (2022).

Morrison, H. et al. Confronting the challenge of modeling cloud and precipitation microphysics. J. Adv. Modeli. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS001689 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Predicting climate anomalies: A real challenge. Atmospheric Ocean. Sci. Lett. 15, 100115 (2022).

Yakubu, A. T., Abayomi, A. & Chetty, N. Machine learning-based precipitation prediction using cloud properties. in Hybrid Intelligent Systems (eds Abraham, A. et al.) 243–252 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96305-7_23.

Gibson, P. B. et al. Training machine learning models on climate model output yields skillful interpretable seasonal precipitation forecasts. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 1–13 (2021).

Mansfield, L. A. et al. Predicting global patterns of long-term climate change from short-term simulations using machine learning. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 3, 1–9 (2020).

Tandon, A., Awasthi, A. & Pattnayak, K. C. Comparison of different machine learning methods on precipitation dataset for Uttarakhand. in 2023 2nd International Conference on Ambient Intelligence in Health Care (ICAIHC) 1–6 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICAIHC59020.2023.10431402 (2023).

Wang, B., Wei, W., Yin, Z. & Xu, L. Using machine learning to analyze the changes in extreme precipitation in southern China. Atmos. Res. 302, 107307 (2024).

Lin, X., Fan, J., Hou, Z. J. & Wang, J. Machine learning of key variables impacting extreme precipitation in various regions of the contiguous United States. J. Adv. Modeli. Earth Syst. 15, e2022MS003334 (2023).

Vitanza, E., Dimitri, G. M. & Mocenni, C. A multi-modal machine learning approach to detect extreme rainfall events in Sicily. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–15 (2023).

Hu, H. & Ayyub, B. M. Machine learning for projecting extreme precipitation intensity for short durations in a changing climate. Geosciences 9, 209 (2019).

Chauhan, A. S., Singh, S., Maurya, R. K. S., Rani, A. & Danodia, A. Spatio-temporal trend analysis and future projections of precipitation at regional scale: A case study of Haryana, India. J. Water Clim. Change 13, 2143–2170 (2022).

Malik, A. & Kumar, A. Spatio-temporal trend analysis of rainfall using parametric and non-parametric tests: Case study in Uttarakhand, India. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 140, 183–207 (2020).

Jaswal, A., Bhan, S., Karandikar, A. & Gujar, M. Seasonal and annual rainfall trends in Himachal Pradesh during 1951–2005. Mausam 66, 247–264 (2015).

Agarwal, S., Mukherjee, D. & Debbarma, N. Analysis of extreme annual rainfall in North-Eastern India using machine learning techniques. AQUA - Water Infrastruct. Ecosyst. Soc. 72, 2201–2215 (2023).

Praveen, B. et al. Analyzing trend and forecasting of rainfall changes in India using non-parametrical and machine learning approaches. Sci. Rep. 10, 10342 (2020).

Ray, R., Chakraborty, S. A. & Discussion on machine learning approach of rainfall prediction. in URSI Regional Conference on Radio Science (USRI-RCRS) 1–4 ((2022). https://doi.org/10.23919/URSI-RCRS56822.2022.10118437

D. Attri, S. & Tyagi, A. Climate profile of India. Contribution Indian Netw. Clim. Change Assess. (Natl. Commun. II). 1, 1–129 (2010).

Nag, P. & Sengupta, S. Geography of India (Concept Publishing Company, 1992).

Lighthill, J. & Pearce, R. P. Monsoon Dynamics (Cambridge University Press, 1981).

Awasthi, A., Pattnayak, K. C., Tandon, A., Sarkar, A. & Chakraborty, M. Implications of climate change on surface temperature in north Indian states: Evidence from CMIP6 model ensembles. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, (2023).

Climate-Know India, I. Profile - Climate - Know India: National Portal of India. https://knowindia.india.gov.in/profile/climate.php (2024).

Rattan, M., Sidhu, G. S. & Singh, S. History of land use in the indo gangetic plains, India and its impact on population: A review. Plant. Arch. 21, 532–537 (2021).

Das, L. & Meher, J. K. Drivers of climate over the western himalayan region of India: A review. Earth Sci. Rev. 198, 102935 (2019).

Jain, S. K., Agarwal, P. K. & Singh, V. P. Physical environment of India. in Hydrology and Water Resources of India (eds Jain, S. K., Agarwal, P. K. & Singh, V. P.) 3–62 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2007) https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-5180-8_1.

Negi, S. S. Discovering the Himalaya (Indus Publishing, 1998).

Verma, O. Climate change and its impacts with special reference to India. in Water, Cryosphere, and Climate Change in the Himalayas: A Geospatial Approach (eds Taloor, A. K., Kotlia, B. S. & Kumar, K.) 39–55 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67932-3_3.

Ramakrishna, Y. S. Current status of agrometeorological services in South Asia, with special emphasis on the Indo-Gangetic Plains (2013).

Singh, N. & Sontakke, N. A. On climatic fluctuations and environmental changes of the Indo-Gangetic Plains, India. Clim. Change 52, 287–313 (2002).

Verma, D. S. K. Environmental Crisis and Conservation (Lulu.com, 2015).

Sikka, D. R. Desert climate and its dynamics. Curr. Sci. 72, 35–46 (1997).

Chopra, V. L. Climate Change and Its Ecological Implications for the Western Himalaya (Scientific, 2013).

Yadav, M. South Asian monsoon extremes and climate change. in Extremes in Atmospheric Processes and Phenomenon: Assessment, Impacts and Mitigation (eds Saxena, P., Shukla, A. & Gupta, A. K.) 59–86 (Springer Nature, Singapore, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-7727-4_4.

Senthilnathan, S. Usefulness of correlation analysis. SSRN Electron. J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3416918 (2019).

Wei, W. et al. Seasonal prediction of summer extreme precipitation over the Yangtze river based on random forest. Weather Clim. Extremes 37, 100477 (2022).

Grazzini, F., Grams, C. & Craig, G. Classification and prediction of days with extreme rainfall using random forest approach. EGU22-11954 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu22-11954 (2022).

Li, K., Huang, G., Wang, S., Razavi, S. & Zhang, X. Development of a joint probabilistic rainfall-runoff model for high-to-extreme flow projections under changing climatic conditions. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2021WR031557 (2022).

Nayak, M. A. & Ghosh, S. Prediction of extreme rainfall event using weather pattern recognition and support vector machine classifier. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 114, 583–603 (2013).

Kalaivani, K., Vijayakumar, N. C., Poovizhi, P., & Selvapandian, D. An efficient rainfall forecasting system using machine learning methods. in Second International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Information and Communication Technologies (ICEEICT) 01–06. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEEICT56924.2023.10157395 (2023).

Shin, K., Kim, K., Song, J. J. & Lee, G. Classification of precipitation types based on machine learning using dual-polarization radar measurements and thermodynamic fields. Remote Sens. 14, 3820 (2022).

Mdegela, L. et al. Extreme rainfall event classification using machine learning for Kikuletwa river floods. Water 15, 1021 (2023).

Shetty, S., Umesh, P. & Shetty, A. The effectiveness of machine learning-based multi-model ensemble predictions of CMIP6 in western ghats of India. Int. J. Climatol. 43, 5029–5054 (2023).

Sharif, M. Simulation of extreme precipitation events using an improved K-nearest neighbor model 389 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784484852.036

Ray, R. & Chakraborty, S. Categorization and prediction of rainfall by machine learning algorithms over Indian landmass. in Advances in Communication, Devices and Networking (eds Dhar, S., Do, D. T., Sur, S. N. & Liu, C. M.) 361–373 (Springer Nature, Singapore, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1983-3_34.

Abed, W. H. A. Detection of high convective precipitation events using advanced machine learning methods (2024).

Hammami, H. & Elasmi, S. Spatial mapping of extreme precipitation events using artificial neural networks. in International Conference on Cyberworlds (CW) 494–495 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/CW58918.2023.00083

Gelaro, R. et al. The modern-era retrospective analysis for research and applications, version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 30, 5419–5454 (2017).

Agarwal, P., Stevenson, D. S. & Heal, M. R. Evaluation of WRF-Chem-simulated meteorology and aerosols over northern India during the severe pollution episode of 2016. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 2239–2266 (2024).

Dai, Z. et al. Long-term MERRA-2 reanalysis data indicate atmospheric environmental changes for three major concentrating-solar-power-plant project areas in Xinjiang, China. Atmosphere 14, 1700 (2023).

Wen, A. et al. Evaluation of MERRA-2 land surface temperature dataset and its application in permafrost mapping over China. Atmos. Res. 279, 106373 (2022).

Rajeev, A., Singh, C., Singh, S. K. & Chauhan, P. Assessment of WRF-CHEM simulated dust using reanalysis, satellite data and ground-based observations. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 49, 1545–1559 (2021).

Gupta, P. et al. Validation of surface temperature derived from MERRA-2 reanalysis against IMD gridded data set over India. Earth Space Sci. 7, e2019EA000910 (2020).

Feng, C. et al. Comprehensive assessment of global atmospheric downward longwave radiation in the state-of-the-art reanalysis using satellite and flux tower observations. Clim. Dyn. 60, 1495–1521 (2023).

Schmeisser, L., Hinkelman, L. M. & Ackerman, T. P. Evaluation of radiation and clouds from five reanalysis products in the Northeast Pacific Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 7238–7253 (2018).

Doelling, D. R. et al. Advances in geostationary-derived longwave fluxes for the CERES synoptic (SYN1deg) product. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 33, 503–521 (2016).

Kato, S. et al. Surface irradiances consistent with CERES-derived top-of-atmosphere shortwave and longwave irradiances. J. Clim. 26, 2719–2740 (2013).

Hamal, K. et al. Evaluation of MERRA-2 precipitation products using Gauge observation in Nepal. Hydrology 7, 40 (2020).

Xu, X., Frey, S. K. & Ma, D. Hydrological performance of ERA5 and MERRA-2 precipitation products over the Great Lakes Basin. J. Hydrology: Reg. Stud. 39, 100982 (2022).

Song, Y. & Wei, J. Diurnal cycle of summer precipitation over the North China Plain and associated land–atmosphere interactions: Evaluation of ERA5 and MERRA-2. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 6031–6046 (2021).

Le, M. H. et al. Assessment of drought conditions over Vietnam using standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index, MERRA-2 re-analysis, and dynamic land cover. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 32, 100767 (2020).

Igbawua, T., Zhang, J., Yao, F. & Zhang, D. Assessment of moisture budget over West Africa using MERRA-2’s aerological model and satellite data. Clim. Dyn. 52, 83–106 (2019).

Cuo, L. & Zhang, Y. Spatial patterns of wet season precipitation vertical gradients on the Tibetan Plateau and the surroundings. Sci. Rep. 7, 5057 (2017).

Wei, J., Dirmeyer, P. A., Wisser, D., Bosilovich, M. G. & Mocko, D. M. Where does the Irrigation Water go? An estimate of the contribution of irrigation to precipitation using MERRA. J. Hydrometeorol. 14, 275–289 (2013).

Rainio, O., Jarmo, T. & Riku, K. Evaluation metrics and statistical tests for machine learning | Scientific Reports (2024). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-56706-x

Vujovic, Z. Classification model evaluation Metrics. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 12, 599–606 (2021).

Hossin, M. Review on evaluation metrics for data classification evaluations. Int. J. Data Min. Knowl. Manage. Process. 5, 01–11 (2015).

Guan, L., Yang, J. & Bell, J. M. Cross-correlations between weather variables in Australia. Build. Environ. 42, 1054–1070 (2007).

Parmar, A., Katariya, R. & Patel, V. A. Review on random forest: An ensemble classifier. in International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (ICICI) 2018 (eds. Hemanth, J., Fernando, X., Lafata, P. & Baig, Z.) 758–763Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03146-6_86

Suthaharan, S. Support vector machine. in Machine Learning Models and Algorithms for Big Data Classification: Thinking with Examples for Effective Learning (ed Suthaharan, S.) 207–235 (Springer US, Boston, MA, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-7641-3_9

Su, W. et al. An XGBoost-based knowledge tracing model. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 16, 13 (2023).

Guo, G., Wang, H., Bell, D., Bi, Y. & Greer, K. KNN model-based approach in classification. in On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems 2003: CoopIS, DOA, and ODBASE (eds Meersman, R., Tari, Z. & Schmidt, D. C.) 986–996 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-39964-3_62.

Manish Lad, A., Mani Bharathi, K., Akash Saravanan, B. & Karthik, R. Factors affecting agriculture and estimation of crop yield using supervised learning algorithms. Mater. Today: Proc. 62, 4629–4634 (2022).

Chowdhury, A., Rosenthal, J., Waring, J. & Umeton, R. Applying self-supervised learning to medicine: Review of the state of the art and medical implementations. Informatics 8, 59 (2021).

Suhaimi, N. A. D., Abas, H., A systematic literature review on supervised machine learning algorithms. PERINTIS Ejournal 10, 1–24 (2020).

Saravanan, R., Sujatha, P. A. & A State of art techniques on machine learning algorithms: A perspective of supervised learning approaches in data classification. in : Second International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS) 945–949 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCONS.2018.8663155.

Tzahor, S. et al. A supervised learning approach for taxonomic classification of core-photosystem-II genes and transcripts in the marine environment. BMC Genom. 10, 229 (2009).

Keuchel, J., Naumann, S., Heiler, M. & Siegmund, A. Automatic land cover analysis for Tenerife by supervised classification using remotely sensed data. Remote Sens. Environ. 86, 530–541 (2003).

Gayan, D., Anca, H. & Andrew, P. R. Frontiers | Improving the Computation of Brier Scores for Evaluating Expert-Elicited Judgements (2021). https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/applied-mathematics-and-statistics/articles/10.3389/fams.2021.669546/full.

Rufibach, K. Use of brier score to assess binary predictions. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 63, 938–939 (2010).

MA, J. et al. (10) (PDF) Analyzing the leading causes of traffic fatalities using XGBoost and grid-based analysis: A city management perspective (2019). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336402347_Analyzing_the_Leading_Causes_of_Traffic_Fatalities_Using_XGBoost_and_Grid-Based_Analysis_A_City_Management_Perspective.

Bichri, H., Chergui, A. & Hain, M. Investigating the impact of train/test Split ratio on the performance of Pre-trained models with Custom datasets. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 15, 331 (2024). https://doi.org/10.14569/ijacsa.2024.0150235.

Vrigazova, B. The proportion for splitting data into training and test set for the bootstrap in classification problems. Bus. Syst. Res. Int. J. Soc. Adv. Innov. Res. Econ. 12, 228–242 (2021).

Mason, S. J. On using climatology as a reference strategy in the brier and ranked probability skill scores. Mon. Weather Rev. 132(7), (2004). https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/mwre/132/7/1520-0493_2004_132_1891_oucaar_2.0.co_2.xml?tab_body=abstract-display.

Acknowledgements

All the authors acknowledge NASA’s POWER Data Access Viewer for providing the climate data. KCP acknowledge the support from the NERC (UK Natural Environment Research Council) AMAZONICA and Amazon Hydrological Cycle grants (NE/F005806/1 and NE/K01353X/1). AT and AA thankful to the University of Petroleum and Energy Studies, Dehradun for providing research facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AT and KCP conceived the study. AT performed the analyses and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results, discussion of the associated mechanisms, and refinement of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tandon, A., Awasthi, A. & Pattnayak, K.C. Efficacy of machine learning in simulating precipitation and its extremes over the capital cities in North Indian states. Sci Rep 15, 10345 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84360-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84360-w