Abstract

Education for patients with type 2 diabetes is an essential part of the treatment and control process. This study aimed to determine the effect of education based on health literacy strategies on adherence to treatment and quality of life in type 2 diabetic patients. This classic experimental study was performed on 94 patients with type 2 diabetes selected by convenient sampling method and then randomly allocated to intervention and control groups. The research instruments were a demographic information questionnaire, a Diabetes Quality of Life Brief Clinical Inventory, and an adherence to treatment questionnaire in patients with chronic disease. The educational intervention was five sessions of the virtual class of 80–90 min. All respondents completed the tools again two months after the intervention. Independent t-tests and paired t-tests were used for data analysis. The difference in the mean score of quality of life in the intervention group between the time before (53.21 ± 7.6) the intervention and two months after (55.28 ± 6.87) was statistically significant (p˂0.05). Comparison of the mean score of quality of life between the control and intervention groups, before the intervention (p > 0.05) and two months after (p > 0.05), neither showed a statistically significant difference. A comparison of the mean scores of adherence to treatment before (69.31 ± 5.32) and after the intervention (70.59 ± 5.21) showed that there was a statistically significant difference in the intervention group (p˂0.001). Comparison of the mean scores of adherence two months after the intervention revealed that, there is a significant statistical difference between the scores of the two groups (p˂ 0.001). Based on the findings of this study, it seems that providing training sessions based on health literacy strategies can improve the quality of life and adherence to treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes constitutes nearly 90% of the roughly 537 million diabetes cases globally1. In 2018, around 5.3 million individuals in Iran were diagnosed with diabetes. Projections indicate that by 2030, this number will rise to 9.2 million2. Patients with type 2 diabetes have to shoulder the heavy burden of treatment or complications of diabetes, leading to a considerable reduction in their quality of life compared to individuals without the disease3. Quality of life is a multidimensional concept that involves various areas of individuals’ lives, including physical status, environmental factors, psychological status, and social ties. According to the definition of the World Health Organization (WHO), quality of life is an individual’s personal perception of their life condition given the culture and value system of the community in which they live, as well as its relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and needs4. The findings of a study showed that all areas of quality of life, including psychological and physical dimensions, were negatively affected by diabetes5.

Constant participation in self-care and self-management in patients with diabetes is related to achieving desirable health consequences through proper blood glucose control, decreasing probable complications, decreasing the risk of death due to diabetes, and finally, improving quality of life. Diabetes self-management proceedings include engaging in behavioral activities suggested by healthcare providers, such as having a healthy diet, adherence to pharmacological treatment, regular physical activity, and blood glucose self-monitoring6.

Based on the WHO, the definition of adherence to treatment in diabetic patients includes compliance with the treatment regimen, including home blood glucose monitoring, food consumption regulation, taking medicine, regular physical activity, foot care, visiting the doctor regularly for periodical examination, and other self-care behaviors such as dental care, wearing appropriate clothes, etc7. The results of studies have shown that compliance with the healthcare team’s recommendations in diabetes treatment accompanies improved treatment outcomes and reduced costs of diabetes8. However, considering the importance of this issue, research has indicated that adherence to treatment in diabetic patients is not well performed9,10,11, which is associated with a high hospitalization rate, increased complications and death and increased healthcare expenses12.

Although the treatment team is responsible for regulating and directing the treatment process, it is the patient who is encountering the problems and complexities of the treatment methods, specifying the importance of the patient’s adherence to treatment; therefore, patient training is considered a substantial part in the treatment of diabetes so that it can be said that training plays a role as important as other parts of treatment13,14.

Health literacy is associated with health outcomes in chronic diseases, including diabetes15. According to the WHO definition, health literacy refers to achieving a level of knowledge, personal skills, and self-confidence to proceed to improve personal and social health along with changing lifestyle and living conditions16,17. Health literacy is positively associated with adherence to treatment18. Insufficient health literacy accompanies the deterioration of health-related quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes, particularly in the mental health field19.

Training patients is taken into account as an important strategy in order to improve patients’ participation in treatment, and it has been recommended to apply various educational strategies to empower diabetic patients to manage their disease20. Electronic health (eHealth) technologies offer a promising solution for aiding in diabetes self-management21. eHealth programs connect individuals to support from peers and friends, especially those with similar chronic conditions or concerns, and to providers who can provide timely access to evidence-based information22. Using health literacy strategies while designing training interventions allows the nurses to express their statements in such a way that patients understand the received information better and attain more ability to take action based on their recommendations23,24. Health literacy strategies consist of using simple and straightforward language, limiting the information provided in each training session and repeating them, using the frequent feedback technique, using images and encouraging patients to ask their questions, and finally, using simple and straightforward media25,26.

Although the effectiveness of interventions based on health literacy strategies on patients with chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes have been examined in studies, limited studies have investigated the impact of this training on the quality of life and treatment compliance of patients with type 2 diabetes. It seems that more studies are needed to strengthen the body of knowledge related to this field. Therefore, since not paying attention to the quality of life and adherence to the treatment regimen in patients with type 2 diabetes has irreparable consequences and is associated with an increase in treatment costs, this study aims to determine the effect of educational intervention based on health literacy strategies on the quality of life and adherence The treatment was carried out in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Materials and methods

Study type

The present classic experimental research was conducted to determine the effect of training based on health literacy strategies on the quality of life and adherence to treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes, with two intervention and control groups and a pretest-posttest in 2020–2021 in the new city of Hashtgerd, Iran.

Research community and sampling method

The target population of this research consisted of patients with type 2 diabetes under the coverage of a health center in the new city of Hashtgerd. Sampling was performed by a convenient method, in such a way that after contacting the patients registered in the list of the national integrated health system by phone, providing information regarding the study, and obtaining the initial consent from the patients to participate in the study, the patients’ information was received to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria or not, and the eligible and inclined individuals were included in the study. The random allocation method for two intervention and control groups in this study was the block-balanced randomization method. This method was administered this way: First, in order to form blocks of four, all states of placement of letters A and B, including AABB-ABBA-ABAB-BAAB-BBAA-BABA, were written together in which A was the intervention and B was the control group conventionally. Then these six states were numbered from one to six. In order to specify the number of required blocks, the sample volume was divided by the type of block (4 blocks), obtaining 24 blocks. From the random number table, 24 random numbers were selected from one to six, and accordingly, among the blocks, the block appropriate to the random number table was selected. After completing the order of the blocks, patients’ random assignment was implemented based on their entrance time (priority was given to phone calls) and also based on the order of the blocks between the two control and intervention groups. The sample size was obtained using the following formula:

α = 0.05 ⇒ zα/2 = 1.96, β = 0.10 ⇒ zβ = 1.28, 1−β = 0.90, (μ1−μ2)/σ = 0.7.

(µ1-µ2) and σ denote the score difference and the standard deviation of adherence to treatment of the intervention and control groups, respectively, obtained from Negarandeh et al.’s27. Taking into consideration almost 10% sample loss, at least 47 samples were estimated in each group.

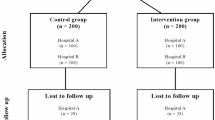

The inclusion criteria were the ability to read and write, having passed at least six months since the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, having no learning and mental disorder (according to the respondents themselves), the ability to communicate, not participating in similar research or training simultaneously with the present study, not having debilitating complications of diabetes such as severe visual defect or blindness, kidney failure, and diabetic foot, and having access to a smartphone and the WhatsApp software and being able to work with it. The exclusion criteria were not attending at least one session of the training class for the patient, contracting acute diseases during the study, and the patient’s refusal to continue participating in the research. The CONSORT flow chart is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Data collection tools

The demographic information researcher-made questionnaire

This questionnaire consists of 15 questions, including age, gender, marital status, education level and disease related and training history questions.

The diabetes quality of life-brief clinical inventory (DQOL-BCI)

The items of this inventory encompass two aspects of care behaviors and satisfaction with disease control. This tool has 15 items with no subscale or domain classification; the items have been provided in two general formats. The total score ranges from 15 to 75. Higher scores denote an improved quality of life28. In this study, the Persian version of this inventory, which was prepared and its validity and reliability assessed by Nasihatkon and colleagues, was used29. The reliability of this tool was assessed by calculating the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α = 0.831) in the present study.

Modanloo’s questionnaire of adherence to treatment

This tool was designed and psychometrically assessed by Modanloo in 2013 (the original version of the questionnaire is in Persian language). This questionnaire contains 40 items in 7 areas: Diligence in treatment, willingness to participate in treatment, adaptability, integration of treatment with life, adherence to treatment, commitment to treatment, and strategy in treatment implementation. To calculate the score of each subscale, the scores of all items of that subscale are added together. The primary scores are turned into scores between zero and 100 (in percent). A score of 75–100% was taken into account as very good adherence to treatment, a score of 50–74% as good adherence to treatment, a 26–49% score as moderate adherence to treatment, and a 0–25% score as poor adherence to treatment30. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of all subscales were above 0.7 in this study.

Intervention and procedure

Ninety-four patients who met the inclusion criteria and were inclined to participate in the research were selected and were randomly assigned to the intervention and control groups using the block-balanced method. Then the online questionnaires were sent to the patients on the WhatsApp platform. After that the patients completed the questionnaires, the respondents of the intervention group attended online classes on the WhatsApp platform in four groups of 10 people and one group of seven people in five 80-90-minute sessions for five weeks. The educational content of these training sessions was designed based on health literacy strategies, i.e., using a simple language or, in other words, not using specialized medical words, decreasing speaking speed, prioritizing and decreasing the number of critical points provided in each training session, using print media with a readability level was designed appropriate to five literacy classes or less, using images, using the teach-back training method, providing a convenient and shame-free environment, and using transparent communication techniques. In order to formulate this educational content, valid scientific texts on diabetes, including books and other sources, were used, the content validity of which was investigated and confirmed by a faculty member, two diabetes nurses, and a diabetes specialist doctor considering the study objectives. Holding the classes was this way: A specific weekday was chosen as a training session, and all the respondents went online at the appointed time. The content of each session was provided to the respondents as a video file one week before beginning each session, and they were supposed to watch the video and make their questions ready to ask in the session on the day of online training. When holding the online training session, first, one of the researchers provided a summary of the training content of that session along with the most critical points as audio files and used related training images and short videos. After providing the training materials, group question-answering was carried out regarding the questions. In order to achieve the teach-back method goal, in each session, two to three respondents were randomly asked to express their impression of the material after each educational material and put it as an audio file in the group. Moreover, after each training session, all respondents were asked to send their opinions along with the points most beneficial to them in a one-two-minute audio file. It is necessary to mention that health literacy strategies and their tools were used to prepare videos, images, and printed media, such as pamphlets provided to the respondents at the end of the training intervention. To prevent potential biases, the intervention group was emphasized not to share the educational content provided to them with others until the end of the study. The control group received routine conventional education. The control group was assured that upon completion of the study, they could receive all the online content if they wished. Two months after finishing the last training session, questionnaires were sent online through WhatsApp software to the respondents of both intervention and control groups. During the research conducting period, eight people from the control group and five people from the intervention group were excluded from the study because of withdrawing from the research and not participating in the post-test; finally, 42 respondents from the intervention group and 39 from the control group completed the study.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 23 software was used for data analysis in this research. Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare the qualitative variables between the two intervention and control groups. Furthermore, the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test and Wilcoxon test, as well as the parametric independent-sample t-test and paired-sample t-test, were used to compare the mean of quantitative variables between the intervention and control groups. The normality of the data distribution was examined and confirmed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. A significance level of less than 0.05 was considered for evaluation.

Results

The respondents’ mean (standard deviation (SD)) age was 49.66 (± 7.58) in the intervention group and 47.53 (± 8.64) in the control group. Other demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1.

The mean (± SD) score of quality of life in the intervention group before the intervention was 53.21 (± 7.60), which reached 55.28 (± 6.87) after the intervention. Examinations revealed that the difference in the mean score of quality of life in the intervention group in the time interval before the intervention implementation and two months after its completion was statistically significant (p = 0.017). Also, an increased score of quality of life was observed in the control group, i.e., the mean (± SD) score reached from 51.87 (± 9.47) before the intervention to 54.41 (± 8.89) two months after the end of the intervention, but the mean difference before and after the intervention is not statistically significant in this group (p = 0.73). The comparison of the mean quality of life scores between the control and intervention groups neither before implementing the intervention (p = 0.57) nor two months after its completion (p = 0.71) showed a statistically significant difference (Table 2).

The mean (± SD) score of adherence to treatment in the respondents before the intervention was 69.59 (± 5.39). The mean (± SD) score of adherence to treatment before implementing the intervention was 69.31 (± 5.32) in the intervention group, which two months after the intervention reached 75.95 (± 7.68). Investigating the results of comparing the mean scores of adherence to treatment in this time interval in the intervention group indicated a statistically significant difference (p˂0.001). The mean (± SD) score of adherence to treatment before the intervention in the control group was 69.86 (± 5.51). Re-measurement of adherence to treatment two months after the intervention showed the mean (± SD) score of 70.59 (± 5.21) in the control group. The difference in mean scores of adherence to treatment before the intervention in the intervention and control groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.62), but two months after finishing the intervention, a statistically significant difference was observed between the scores of the two groups (p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Discussion

The present research was conducted to determine the impact of training based on health literacy strategies on quality of life and adherence to treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Quality of life

Overall, the results of this research indicate an increased total quality of life score in the intervention group and the control group over time. However, after the intervention, the process of increased quality of life score in the intervention group was more than in the control group. The result of this research is in line with Mohammadi et al.’s study (2018) on measuring the effect of self-care education on the quality of life of patients with type 1 diabetes. The findings of this study also revealed no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups before and after the intervention; however, the quality of life improved in the intervention group after the intervention31. The data collection tools and the procedure of implementing the training intervention were similar in these two studies, but the research samples were different in terms of the type of diabetes. In addition, the findings of Saghaee et al.’s study indicated that both “face-to-face” and “booklet use” educational methods resulted in increased quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes, which is not consistent with the results of the current research. The reasons for different results can be attributed to the material, content, and the number of training sessions and also the training method provided as virtual in the present study and in-person in the mentioned study32. The results of another study indicated the positive impact of the used training program on the quality of life of diabetic patients33, which is not in line with the current research results. Some of the possible reasons for this discrepancy include the different number of research samples and the respondents’ age difference. Moreover, in the educational content of this study, there are things such as training compatibility and healthy adaptation to diabetes, somehow interfering with the respondents’ emotional, psychological, and cognitive dimensions, and according to the researchers’ opinions, these dimensions directly or indirectly influence the quality of life; therefore, it may be another reason for the difference in the results of these two studies.

The results of another study regarding assessing the effect of the self-management training program on the quality of life of patients with type 2 diabetes indicated that self-management training in diabetes led to increasing the quality of life of patients with type 2 diabetes34. The results of this study are not in line with the present research. This discrepancy may be due to the different training methods used, which in-person problem-solving method was used in the mentioned study.

Given the results of the current study and other investigated studies, it can be said that holding training sessions for patients with type 2 diabetes is effective in promoting their quality of life. Determining the impact of training intervention based on health literacy strategies on the quality of life of patients with type 2 diabetes and the factors influencing it needs conducting more research on the population of patients with type 2 diabetes in different regions. Maybe it is required to use more samples with different follow-up time intervals in the subsequent studies to assess the effect of this training intervention.

Adherence to treatment

Overall, the results of the present research indicated a high total score of adherence to treatment both in the intervention group and in the control group over time. However, after the intervention, the process of increasing the adherence to treatment score in the intervention group was higher than in the control group. The findings of the current research are consistent with Najafpour et al.’s study on determining the effect of a training intervention based on the social marketing model on adherence to medication among patients with type 2 diabetes35. Considering that this study has been designed as a part of the training content of the present research aiming at affecting adherence to treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes in terms of the number of samples, the number and duration of training sessions, and the training content, it can be concluded that designing and implementing types of training aiming to affect adherence to treatment, whether pharmacological treatment or other treatments prescribed in type 2 diabetes, can take a positive step to improve adherence to treatment by patients.

The findings of Supachaipanichpong et al.’s study showed that the intervention group significantly changed the level of adherence to medication after the pharmacological training intervention compared to the control group36. Although only adherence to medication was considered by the researchers in the mentioned study, while both adherence to medication and the importance of adherence to all aspects of type 2 diabetes treatment was emphasized in the present research, the importance of providing training regarding adherence to treatment to patients with type 2 diabetes can be understood through the similarity of the results of the two studies. Also, the findings of Mohammed et al.’s study, one of the objectives of which was to determine the effectiveness of a structured training program on improving adherence to treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes, just like the results of the present study, indicated considerable progress in the level of adherence to treatment in the first and second follow-up than before implementing the training program31. Given the results of the present research and other similar studies, it can be concluded that holding virtual and in-person training sessions for patients with type 2 diabetes leads to improving their adherence to treatment, so that some studies, such as Sartori et al.’s study, on the adherence to pharmacological treatment of patients with diabetes and high blood pressure following a training intervention using WhatsApp software indicated a considerable clinical effect (15% increase) after the training intervention on adherence to medication37. Therefore, it can be concluded that training interventions are effective in adherence to treatment, and training interventions can effectively improve adherence to treatment in different populations with different characteristics by controlling the interventional variables reported in previous studies. Finally, it should be acknowledged that adherence to treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes is among the determinant factors influencing the treatment process, satisfaction with treatment, and, consequently, desirable control of blood glucose levels. Given the importance of this variable, the result of the current research revealed that in the current study population, similar to other studies in various regions of Iran and the world, these two variables had not reached an acceptable level yet, which can culminate in the failure to achieve therapeutic goals.

Patients with type 2 diabetes who did not have access to smartphones or WhatsApp software were not able to participate in the research. Another limitation of this research, which held classes online, was the limited use of the strategy of establishing obvious relationship methods in-person with the intervention group respondents. In order to eliminate this limitation, the researcher was continuously in contact with the respondents by using the features of WhatsApp software (such as sending audio or video files) and even by phone when necessary to resolve their ambiguities and questions.

Implications

The results of this study can help other researchers in mapping out future studies on the quality of life and treatment adherence of patients with type 2 diabetes. By addressing the limitations present in this study, further research can be conducted on the application of this training method to improve the quality of life and treatment adherence in other chronic diseases, such as hypertension, heart disease, and more.

Additionally, the results of this research can assist managers and planners of nursing and nursing education in deciding to incorporate health literacy strategies into the community health nursing curriculum, particularly in discussions related to health promotion. Also, the findings of this study can help clinical nurses to make decisions and choose effective teaching methods for patients with type 2 diabetes to improve their quality of life and accept the treatment regimen.

Conclusion

According to the study aim, the findings of this research indicated that holding training sessions based on health literacy strategies could affect the improvement of quality of life and adherence to treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes. It is suggested that in future research, the effectiveness of educational intervention based on health literacy, which is held virtually, should be investigated in studies with a longer period and more frequent evaluations.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- HbA1C:

-

Hemoglobin A1C

- DQOL-BCI:

-

The Diabetes Quality of Life-Brief Clinical Inventory

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Ahmad, E., Lim, S., Lamptey, R., Webb, D. R. & Davies, M. J. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 400(10365), 1803–1820 (2022).

Jalilian, H. et al. Economic burden of type 2 diabetes in Iran: a cost-of-illness study. Health Sci. Rep. 6(2), e1120 (2023).

Pham, T. B. et al. Effects of Diabetic complications on Health-Related Quality of Life Impairment in Vietnamese patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 4360804 (2020).

Al-Taie, N., Maftei, D., Kautzky-Willer, A., Krebs, M. & Stingl, H. Assessing the quality of life among patients with diabetes in Austria and the correlation between glycemic control and the quality of life. PCDE 14(2), 133–138 (2020).

Asaad, Y. A., Othman, S. M., Ismail, S. A. & Al-Hadithi, T. S. Quality of life of type 2 diabetic patients in Erbil city. Zanco J. Med. Sci. (Zanco J. Med. Sci) 23(1), 35–42 (2019).

Adu, M. D., Malabu, U. H., Malau-Aduli, A. E. & Malau-Aduli, B. S. Enablers and barriers to effective diabetes self-management: a multi-national investigation. PLoS ONE 14(6), e0217771 (2019).

Hashemi, S. M. & Bouya, S. Treatment adherence in Diabetic patients: an important but forgotten issue. J. Diabetes Nurs. 6(1), 341–351 (2018).

Paquot, N. Deleterious effects of lack of compliance to lifestyle and medication in diabetic patients. Rev. Med. Liege 65(5–6), 326–331 (2010).

Alshehri, K. A., Altuwaylie, T. M., Alqhtani, A., Albawab, A. A. & Almalki, A. H. Type 2 diabetic patients adherence towards their medications. Cureus 12(2) (2020).

Kumar, H., Abdulla, R. A. & Lalwani, H. Medication adherence among type 2 diabetes Mellitus patients: A Cross Sectional Study in Rural Karnataka (India). Athens J. Health Med. Sci. 8(2), 107–118 (2021).

Polonsky, W. H. & Henry, R. R. Poor medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: recognizing the scope of the problem and its key contributors. Patient Prefer. Adher. 10, 1299–1307 (2016).

Barasa Masaba, B. & Mmusi-Phetoe, R. M. Determinants of non-adherence to treatment among patients with type 2 diabetes in Kenya: a systematic review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 13, 2069–2076 (2021).

Hinkle, J. L. & Cheever, K. H. Brunner and Suddarth’s Textbook of medical-surgical Nursing (Wolters kluwer India Pvt Ltd, 2018).

Karkashian, C. & Schlundt, D. Diabetes. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies—Evidence for Action (World Health Organization, 2003).

Protheroe, J., Rowlands, G., Bartlam, B. & Levin-Zamir, D. Health literacy, diabetes prevention, and self-management. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 1298315 (2017).

Kickbusch, I., Pelikan, J. M., Apfel, F. & Tsouros, A. Health literacy: WHO Regional Office for Europe (2013).

Sørensen, K. et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public. Health 12(1), 1–13 (2012).

Miller, T. A. Health literacy and adherence to medical treatment in chronic and acute illness: a meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 99(7), 1079–1086 (2016).

Al Sayah, F., Qiu, W. & Johnson, J. A. Health literacy and health-related quality of life in adults with type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Qual. Life Res. 25(6), 1487–1494 (2016).

Reisi, M. et al. Effects of an educational intervention on self-care and metabolic control in patients with type II diabetes. J. Client-Center. Nurs. Care 3(3), 205–214 (2017).

Rollo, M. E. et al. The feasibility and preliminary efficacy of an eHealth Lifestyle Program in Women with recent gestational diabetes Mellitus: a pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 17, 19 (2020).

Johnson, C. M. et al. Learning in a virtual environment to improve type 2 diabetes outcomes: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Form. Res. 7, e40359 (2023).

Javadzade, S. H., Mostafavi, F., Sharifirad, G. & Reisi, M. Investigating the effect of education on improving nurses’ skills to apply health literacy strategies in patient education. Fourth National Conference on Strategies for Improving the Quality of Nursing and Midwifery Services (Yazd Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, 2014).

Javadzade, S. H., Mostafavi, F., Sharifirad, G. & Reisi, M. Perceived behavioral control: The best predictor of nurses’ intent and behavior in applying health literacy strategies to patient education. Fourth National Conference on Research in the Development of New Health-Care (Birjand University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, 2015).

Sudore, R. L. & Schillinger, D. Interventions to improve care for patients with limited health literacy. J. Clin. Outcomes Manag. JCOM 16(1), 20–29 (2009).

Wittink, H. & Oosterhaven, J. Patient education and health literacy. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 38, 120–127 (2018).

Negarandeh, R., Mahmoodi, H., Noktehdan, H., Heshmat, R. & Shakibazadeh, E. Teach back and pictorial image educational strategies on knowledge about diabetes and medication/dietary adherence among low health literate patients with type 2 diabetes. Prim. Care Diabetes 7(2), 111–118 (2013).

Burroughs, T. E., Desikan, R., Waterman, B. M., Gilin, D. & McGill, J. Development and validation of the diabetes quality of life brief clinical inventory. Diabetes Spectr. 17(1), 41–49 (2004).

Nasihatkon, A. A. et al. Determining the reliability and validity of the clinical quality of life questionnaire for diabetic patients (DQOL) in Persian. IJDM 11(5), 483–487 (2012).

Tanharo, D. et al. Adherence to treatment in diabetic patients and its affecting factors. psj 17(1), 37–44 (2018).

Mohammed, E. R., Ahmed, N. M. & Abd Elkhalik, E. F. Effectiveness of structured teaching program on improvement of diabetic patient’s health information, treatment adherence and glycemic control. Int. J. Nurs. Didactics 10(05), 01–14 (2020).

Alamdari, A., Taheri, R., Afrasiabifar, A. & Rastian, M. Comparison of the Impact of Face-to-face education and Educational Booklet methods on Health-related quality of life in patient with type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Care Skills 1(2), 75–80 (2020).

Saghaee, A. et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of persian diabetes self-management education in older adults with type 2 diabetes at a diabetes outpatient clinic in Tehran: a pilot randomized control trial. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 19(2), 1491–1504 (2020).

Ghiyasvandian, S., Salimi, A., Navidhamidi, M. & Ebrahimi, H. Assessing the effect of self-management education on quality of life of patients with diabetes mellitus type 2. J. Knowl. Health. 12(1), 50–56 (2017).

Najafpour, Z., Zeidi, I. M. & Kalhor, R. The effect of educational intervention on medication adherence behavior in patients with type 2 diabetes: application of social marketing model. Clin. Diabetol. 10(4), 359–369 (2021).

Supachaipanichpong, P., Vatanasomboon, P., Tansakul, S. & Chumchuen, P. An education intervention for medication adherence in uncontrolled diabetes in Thailand. Pac. Rim Int. J. Nurs. Res. 22(2), 144–155 (2018).

Sartori, A. C., Rodrigues Lucena, T. F., Lopes, C. T., Picinin Bernuci, M. & Yamaguchi, M. U. Educational intervention using WhatsApp on medication adherence in hypertension and diabetes patients: a randomized clinical trial. Telemed. e-Health 26(12), 1526–1532 (2020).

Funding

This study was supported by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. The funder had no role in the design and writing of the manuscript and will have not in data collection and analysis of data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MR-N and MH designed the study; MR-N collected the data; and MH, MR-N, and MN analyzed the data. As well, MR-N, MH and SH authored the manuscript, and PV and MN reviewed, edited, and approved the manuscript prior to its submission for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The respondents were assured that their data would remain confidential. Oral (by phone) and written (by creating a specific option in the online questionnaire for this purpose) informed consent was obtained from the respondents to participate in this research. Also, it has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1399.036). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roshan-Nejad, M., Hosseini, M., Vasli, P. et al. Effect of health literacy-based teach-back training on quality of life and treatment adherence in type 2 diabetes: an experimental study. Sci Rep 15, 551 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84399-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84399-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Multidimensional assessment of large language model responses to patient questions on gestational diabetes mellitus

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Unmasking mental distress: exploring the spectrum of cognitive distortions associated with symptoms of anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation

Cognitive Processing (2025)

-

Postoperative feedback-oriented health education in ambulatory robot-assisted adrenalectomy: a single-center nursing intervention cohort study

Journal of Robotic Surgery (2025)