Abstract

We investigated subjective symptoms during driving in 227 glaucoma patients at a driving assessment clinic. Patients underwent testing with the Humphrey Field Analyzer 24–2 (HFA 24–2) and a driving simulator (DS) with eye tracking. Patients reported whether they experienced symptoms during daily driving, such as fear or difficulty seeing under certain conditions. The integrated visual field (IVF) was calculated from HFA 24–2 data. The number of collisions in DS scenarios and eye movements during DS testing was recorded, and factors related to the presence of subjective symptom during driving were analyzed using multivariate logistic regression, with subjective symptoms as the dependent variable. Overall, 145 patients (63.9%) did not report subjective symptoms during driving. Rates of these symptoms were 22.9%, 36.6%, and 41.7% for mild, moderate, and severe glaucoma, respectively (P = 0.030). Patients with symptoms had worse better-eye mean deviation (MD) (P = 0.012) and lower IVF sensitivity in the superior hemifield (P < 0.002). Logistic regression revealed a significant association between symptoms and decreased superior IVF sensitivity from 0° to 12° (P = 0.0029; OR: 1.07). Our study highlights that many glaucoma patients, even with severe disease, may not be aware of visual symptoms during driving, though superior IVF mean sensitivity contributed to subjective symptoms during driving.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glaucoma is known to have few subjective symptoms, progressing without causing symptoms until the disease is advanced and there is substantial neural damage1. Epidemiological studies in many different populations have repeatedly documented that 50% to 90% of persons with open-angle glaucoma are unaware of their condition2,3,4, possibly due to the lack of subjective symptoms.

Crabb et al. found that glaucoma patients frequently experienced a combination of blurred vision and missing areas of the visual field, which appear to be the primary visual indicators of the condition. Twenty-six percent of patients were unaware of their visual field loss. 5 Hu et al. reported that the most common symptoms reported by glaucoma patients were needing more light and blurry vision. 6 Recently, Shah et al. showed that a subset of specific patient-reported symptoms explained 62% of the variance in the severity of visual field damage.7 However, no previous studies have examined the presence or absence of subjective symptoms during driving.

The relationship between motor vehicle collisions (MVCs) and visual field impairment is still poorly understood. We established the first driving assessment clinic at a Japanese eye hospital to educate drivers with visual field impairment, using a driving simulator (DS), on scenarios that pose MVC risks specific to them with the goal of reducing MVCs caused by visual field impairment.8,9 At this driving assessment clinic, we experienced that many patients were surprised to find out for the first time that they had visual field defects after they overlooked a traffic light or caused an accident when a car suddenly rushed out from the left or right. Therefore, we thought it would be meaningful to investigate what kind of visual field impairment patterns affect the presence or absence of subjective symptoms during driving to teach patients with glaucoma how to drive safely. Thus, in the present study, we investigated subjective symptoms during driving among patients with glaucoma, as well as their clinical characteristics, at a driving assessment clinic.

Results

A total of 227 patients (147 men, 80 women) were included. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) age was 63.2 ± 12.4 years (range 26–87 years), the better-eye MD was -11.83 ± 6.70 dB (range -28.34 to + 5.30 dB), and the mean worse eye MD was -19.51 ± 6.45 dB (range -31.85 to + 0.78 dB), respectively. There were no significant differences in age, sex, or MD between patients from the Nishikasai Inouye Eye Hospital and the Niigata University Hospital. In this study, no patients were suspected of having dementia based on the MMSE assessment for cognitive impairment.

The figure shows an example of results from a glaucoma patient who missed a traffic signal in the DS, causing a motor vehicle collision, due to a superior visual defect (Fig. 1). The patient had no subjective symptoms during daily driving. After learning at our clinic that she had missed the signal due to this superior visual defect (Fig. 2), the patient continued to drive while being careful at traffic signals and had no accidents or violations for two years.

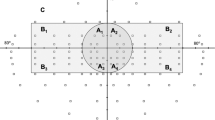

Results from a glaucoma patient who missed a traffic signal in the driving simulator, causing a motor vehicle collision. She had no subjective symptom during driving. (a) The subject was a 77-year-old woman who had no subjective symptom during driving. She had primary open-angle glaucoma with best-corrected visual acuity in the better eye of 20/20. The top left and top right show grayscale plots and visual field values obtained with the Humphrey Field Analyzer 24-2 (HFA 24-2) for the left and right eyes, respectively. The mean deviation of her visual field was -24.69 dB in the right eye and -11.07 dB in the left eye. The integrated visual field (IVF) (lower left) and the Esterman visual field test (lower right) show that this patient’s corresponding monocular visual field damage resulted in a binocular defect in the upper hemifield of the central field of view.

Screenshots of the simulations and IVF subfield maps. Left: In the screenshots, the red points (indicated with yellow arrows) show the gaze point. The driver’s vehicle had a simulated speed of 50 km/hour. The signal changed from yellow to red. Right: IVF superimposed over a recording of the DS test, centered over the gaze point (red point), to compare it with the area of visual field impairment. The signal is within the area of the visual field defect, suggesting that the patient’s superior visual field defect made it difficult to notice the signal changing from yellow to red, causing her to miss the signal and collide with a vehicle that came from the left.

Of the 227 patients, 145 (63.9%) did not report subjective symptoms during daily driving.There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients with subjective symptoms by geographical location: 65 of 109 patients (59.6%) lived in Tokyo and 80 of 118 (67.8%) patients lived in Niigata (P = 0.2; Chi-squared test).

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics and vision characteristics of the study subjects with or without subjective symptoms during daily driving. The glaucoma patients with subjective symptoms during driving had worse better-eye MD than those who without subjective symptoms (P = 0.012). The mean sensitivity of the superior IVF0-12, superior IVF13-24, and inferior IVF13-24 was also significantly lower in the glaucoma patients with subjective symptoms during driving (P = 0.0002, P = 0.0013, and P = 0.0008, respectively). There were no differences between the groups with and without subjective symptoms during driving in age, gender, MMSE score, driving exposure time, number of MVAs in the previous five years, worse-eye visual acuity, worse-eye MD, Esterman score, or inferior hemifield IVF0-12. The self-reported prevalence of MVAs was 29.3% (24/82) in the group with subjective symptoms during driving and 18.6% (27/145) in the group without subjective symptoms.

Table 2 shows the results in DS. Data were not available for 34 cases (14 cases with subjective symptoms during driving and 20 cases without subjective symptoms during driving) due to two reasons: (1) experiencing simulator sickness during the main test, and (2) patients were excluded from the analysis because of poor eye-tracking data (more than 50% of data missing) in video clip recordings. One or more collisions in the DS were observed in 80.9% (55/68) of the group with subjective symptoms during driving and in 72.0% (90/125) in the group without subjective symptoms (P = 0.53). There were no significant differences in the number of collisions in the DS or horizontal and vertical spread of search between the two groups (P = 0.63, 0.93, and 0.18).

Of the 227 patients with glaucoma, 48 were classified as mild, 71 as moderate, and 108 as severe. There was a statistically significant association between glaucoma severity and the rate of subjective symptoms during daily driving: 22.9% of the mild group, 36.6% of the moderate group, and 41.7% of the severe group had subjective symptoms during driving. The presence of subjective symptoms during driving was higher in the severe glaucoma group (P = 0.030, Cochran-Armitage trend test) (Table 3).

We performed two separate logistic regression analyses of the study participants for different areas of the IVF. Analysis 1 showed that the presence of subjective symptoms was significantly associated with mean sensitivity in the superior IVF0-12 (P = 0.0029; OR: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.12) (Table 4). Analysis 2 showed that presence of subjective symptoms was not significantly associated with mean sensitivity in the superior and inferior IVF13-24 (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, we attempted to investigate subjective symptoms during daily driving by glaucoma patients at a driving assessment clinic. We found that 145 of 227 patients (63.9%) did not report subjective symptoms during daily driving. In a previous study, Shono et al. examined 250 newly diagnosed glaucoma patients in Tajimi Municipal Hospital (Gifu, Japan), of whom 233 (93.2%) reported being unaware of any visual abnormalities.10 Furthermore, they reported that 140 of 149 patients (94.0%) in the mild stage, 51 of 56 patients (91.1%) in the moderate stage, and 41 of 45 patients (91.1%) in the severe stage were previously undiagnosed because they were unaware of the disease. This rate of subjective symptoms is lower than in our study; a difference that may be attributable to the fact that the report by Shono et al. was based on “subjective symptoms,” while our study focused on “subjective symptoms during daily driving.” We specifically investigated the presence or absence of visibility difficulties limited to driving situations. When driving, there are many situations in which people feel danger and need to pay attention, such as checking traffic signals, looking at signs, and watching out for cars and people running out from the left or right, which may explain why people noticed the “difficulty in seeing” in more situations than in daily life.

We also found that as the stage of glaucoma progressed from mild to moderate to severe, the percentage of patients with subjective symptoms increased to 22.9%, 36.6%, and 41.7%, respectively. Sabapathypillai et al11 investigated the relationship between self-perceived driving difficulty, driving avoidance, and negative emotions regarding driving and performance during an on-road driving test. They found that 26 of 109 glaucoma patients (23.8%) self-reported negative emotions, and that the proportion increased with worsening glaucoma severity: 11.3% in mild, 33.3% in moderate, and 42.8% in advanced glaucoma. The proportion of glaucoma patients who had difficulty seeing when driving increased as the disease progressed from early to middle to late stages, a result that is similar to our study. This should be taken into consideration in daily clinical practice by general ophthalmologists.

The patients’ driving ability was assessed using a driving simulator. There was no significant difference in the number of collisions in the DS or the horizontal and vertical spread of search between patients with and without subjective symptoms during driving. Horizontal spread of search has been noted to be reduced in novice drivers compared to experienced drivers.12 Glaucoma patients can observe hazardous events by increasing their visual search activity to compensate for visual field impairment, thereby avoiding collisions, as suggested by some studies.13,14,15,16 Our results imply that being aware of glaucomatous change, i.e., having subjective symptoms during driving, does not lead to safer driving, and that detailed explanations are necessary when teaching safe driving.

In the group with subjective symptoms, the mean retinal sensitivity of the superior IVF was decreased. Our results indicate that lower mean sensitivity in the superior IVF hemifield contributes significantly to subjective symptoms during driving. Yamasaki et al. 17investigated the association between driving self-regulation and glaucomatous visual field defect patterns. They reported that only IVF deterioration in the superior area was associated with driving avoidance at night, in rain, and in fog. This finding is consistent with our study. Since there are many objects in high locations that must be observed while driving, such as traffic signals and signs, a worsening superior IVF will lead to subjective symptoms during driving.

We previously reported that the inferior hemifield was associated with the incidence of MVCs with oncoming cars in patients with advanced glaucoma.9 However, the current findings suggest that many of these patients are unaware of their increased risk. In order to ensure safe driving for patients with visual field impairment, it is crucial to identify the specific areas of the visual field in which defects are associated with MVC involvement, considering that “few people have subjective symptoms while driving.”

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to study “subjective symptoms during driving.” We found that subjective driving symptoms in patients are associated with decreased superior IVF0-12 mean sensitivity. Since subjective symptoms play an important role in the management of glaucoma, we believe that our study will be useful in providing lifestyle guidance to glaucoma patients.

Our study has several limitations. First, it is based on self-reported “subjective symptoms during driving,” and lacks granularity as to which specific visual symptoms were associated with vision characteristics. In thinking about how this study may shape clinical practice and/or invite further study, we consider that it would be more useful to understand which specific symptoms are correlated with worsening clinical parameters, such as the mean retinal sensitivity of the superior IVF. However, it has been said that asking patients about their symptoms may optimize patient-physician communication, 7 so we believe that it is significant to focus on the “presence or absence of subjective symptoms during driving.” Second, because only patients at a driving assessment clinic were included, there is a potential of bias. The driving assessment clinic deals with patients with severe glaucoma, and better-eye MD in our patients was -11.83 ± 6.70 dB (range, -28.34–5.30 dB). Therefore, it is possible that our patients had more subjective symptoms during driving than glaucoma patients in general clinics. However, it is notable that only 41.7% of patients with severe glaucoma had subjective symptoms during driving. We should guide our patients with the understanding that few patients have subjective symptoms, even when driving.

In Japan, conditions such as epilepsy, dementia, and stroke are explicitly listed as “specified diseases that may impede safe driving and can be grounds for the revocation or suspension of a driver’s license.” However, eye diseases such as glaucoma or retinitis pigmentosa are not included in this category. Therefore, it is not mandatory for an ophthalmologist to report to the authorities if a patient seems unable to drive a car safely. Furthermore, it is likely that, as in other countries, many individuals with glaucoma may not be aware of their visual field impairment due to the lack of symptoms. This emphasizes that the issue of driving with undiagnosed glaucoma is not unique to Japan but may be a global concern.

In conclusion, we believe that our study is a valuable first step toward future, more precise investigations of patterns of visual field impairment that affect the ability to drive safely. An improved understanding of the subjective symptoms of glaucoma during driving will be helpful in glaucoma management.

Materials and methods

Subjects

A total of 227 glaucoma patients (109 patients at Nishikasai Inouye Eye Hospital and 118 patients at Niigata University Hospital) at a driving assessment clinic completed a written questionnaire. The questions were selected from a survey used at a Japanese driving license examination center (DLEC) 18; the questions asked about a range of aspects of driving habits and history (e.g., years since acquisition of first driving license, time spent driving per week) and self-reported motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) in the previous five years. Subjective symptoms during daily driving were defined as the presence of at least one of the following four items: difficulty seeing at night, difficulty seeing in the rain, difficulty seeing traffic signals, and fear of driving. The patients were examined at the Nishikasai Inouye Eye Hospital and the Niigata University Hospital between July 2019 and July 2022. Patients with other diseases with visual field impairment were not included in this analysis. All participants were active drivers who had driven within at least the previous 3 months and were currently licensed to drive in Japan, which requires either 1) binocular visual acuity of 20/30 or 2) monocular visual acuity of 10/30, with a minimum monocular visual field of 150 degrees horizontally on a modified Förster perimeter.

All participants received a complete ophthalmologic examination, including best-corrected visual acuity, a slit lamp examination, intraocular pressure measurement with Goldmann applanation tonometry, gonioscopy, a stereoscopic fundus examination, and standard automated perimetry with the Humphrey Visual Field Analyzer Swedish Interactive Threshold Algorithm–Standard 24–2 program (HFA 24–2: Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA) and the binocular Esterman program. The patients who had glaucomatous visual field defect in at least one eye were included in this study. The definition of glaucomatous visual field defects was based on the Anderson and Patella criteria. 19 We excluded patients with cataract or other non-glaucoma ocular diseases that could cause visual field defects after a basic ophthalmic exam. Participants were also excluded if they had unreliable visual fields, defined as fixation loss > 33%, a false-positive rate > 15%, or a false-negative rate > 20%. The severity of glaucoma was classified using the better-eye visual field mean deviation (MD) as follows: -6 dB or more (mild), from -6 dB or less to -12 dB or more (moderate), and -12 dB or less (severe). 19.

The binocular integrated visual field (IVF) was calculated by merging pairs of results from monocular HFA 24–2 tests. The patients’ best point-by-point monocular sensitivity was used20,21. We evaluated mean IVF sensitivity in the central area of the inferior and superior hemifields within 0º to 12º (IVF0-12) and within 13º to 24º (IVF13-24) of the fixation point.

Cognitive function was assessed to screen for potential cognitive impairment among participants using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). This test was developed by Folstein et al. in 1975 and is widely used as a brief screening test for dementia and as a measure of global cognitive function. The MMSE total score ranged from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating poorer cognitive ability.22.

This study was performed following the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Inouye Eye Hospital Ethics Committee (approval number: 202109–4) and the Ethics Committee of Niigata University (approval number: 2015–2566). All patients provided written informed consent after receiving an explanation of the study procedures and possible risks.

Driving simulator

All participants in this study underwent DS (Honda Motor Co., Tokyo) testing with eye tracking (Tobii Pro Nano). The DS, previously described in detail,9 included 15 driving scenarios. The examinees undertook a 2-min practice session followed by the 5-min main test. The simulated car ran at a constant speed. The subjects had no steering wheel control and only applied the brakes when they felt in danger. If an examinee reported feeling simulator sickness during the practice session, further testing was immediately abandoned. The main test contained 15 scenarios depicting such situations as coming to a stop sign, traffic light, or road hazard, or another car suddenly rushing out in front. The number of collisions in all 15 scenarios was recorded.

Eye movements during DS testing were measured with eye tracking, and data for the horizontal and vertical spread of search12,23 were obtained from the standard deviation of the x and y coordinates, respectively, of eye movement during the 5-min test.

Statistical analysis

The patients were divided into two groups: those with subjective symptoms during daily driving and those without symptoms. Differences in demographic characteristics between the two groups were determined using the t-test, χ2 test, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. We assessed the relationship between glaucoma severity and the rate of subjective symptoms during driving using the Cochran-Armitage test.

We also performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis of the glaucoma patients. The dependent parameter was the presence or absence of subjective symptoms during driving and the independent parameters were age, driving exposure time, visual acuity, Esterman score, and mean sensitivity of the IVF subfields (analysis 1: the superior and inferior IVF0-12; analysis 2: the superior and inferior IVF13-24). All statistical analyses were made with JMP (version 14.0). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Author contributors

The authors who contributed to the design and conduct of the study were S.KS.; to the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data were S.KS, T.F.; and to the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript was S.KS, T.F., M.T, A.M., K.I.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the currentstudy are not publicly available due to patient data privacy policy, but are available from the corresponding author (S.KS) on reasonable request.

References

Weinreb, R. N. The Pathophysiology and Treatment of Glaucoma A Review. 311, 1901–1911 (2014).

Iwase, A. et al. The prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in Japanese: the Tajimi Study. Ophthalmology 111, 1641–1648 (2004).

Dielemans, I. et al. The Prevalence of Primary Open-angle Glaucoma in a Population-based Study in The Netherlands: The Rotterdam Study. Ophthalmology 101, 1851–1855 (1994).

Shen, S. Y. et al. The prevalence and types of glaucoma in Malay people: The Singapore Malay eye study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49, 3846–3851 (2008).

Crabb, D. P., Smith, N. D., Glen, F. C., Burton, R. & Garway-Heath, D. F. How does glaucoma look?: Patient perception of visual field loss. Ophthalmology 120, 1120–1126 (2013).

Hu, C. X. et al. What do patients with glaucoma see? Visual symptoms reported by patients with glaucoma. Am. J. Med. Sci. 348, 403–409 (2014).

Shah, Y. S. et al. Patient-Reported Symptoms Demonstrating an Association with Severity of Visual Field Damage in Glaucoma. Ophthalmology 129, 388–396 (2022).

Kunimatsu-Sanuki, S. et al. An assessment of driving fitness in patients with visual impairment to understand the elevated risk of motor vehicle accidents. BMJ Open, (2015).

Kunimatsu-Sanuki, S. et al. The role of specific visual subfields in collisions with oncoming cars during simulated driving in patients with advanced glaucoma. British Journal of Ophthalmology 896–901 (2016) https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-308754.

Shono, Y., Iwase, A., Aoyama, A. & Yamamoto, T. Subjective symptoms of glaucoma patients found in a large-scale eye disease screening project. Japan. Rev. Clin. Ophthalmol. 100, 496–498 (2006).

Sabapathypillai, S. L. et al. Self-Reported Driving Difficulty, Avoidance, and Negative Emotion With On-Road Driving Performance in Older Adults With Glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 241, 108–119 (2022).

Crundall, D. E. & Underwood, G. Effects of experience and processing demands on visual information acquisition in drivers. Ergonomics 41, 448–458 (1998).

Kasneci, E. et al. Driving with binocular visual field loss? A study on a supervised on-road parcours with simultaneous eye and head tracking. PLoS One 9, e87470 (2014).

Kübler, T. C. et al. Driving with glaucoma: Task performance and gaze movements. Optometr. Vis. Sci. 92, 1037–1046 (2015).

Lee, S. S. Y., Black, A. A. & Wood, J. M. Scanning Behavior and Daytime Driving Performance of Older Adults with Glaucoma. J Glaucoma 27, 558–565 (2018).

Adrian, J. et al. Driving behaviour and visual compensation in glaucoma patients: Evaluation on a driving simulator. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 50, 420–428 (2022).

Yamasaki, T. et al. Binocular superior visual field areas associated with driving self-regulation in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 105, 135–140 (2021).

Okamura, K. et al. Association between visual field impairment and involvement in motor vehicle collision among a sample of Japanese drivers. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol Behav. 62, 99–114 (2019).

Anderson DR & Patella VM. Automated Static Perimetry. 2nd Edition. (St Louis: CV Mosby, 1999).

Nelson-Quigg, J. M., Cello, K. & Johnson, C. A. Predicting binocular visual field sensitivity from monocular visual field results. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41(8), 2212–2221 (2000).

Crabb, D. P., Fitzke, F. W., Hitchings, R. A. & Viswanathan, A. C. A practical approach to measuring the visual field component of fitness to drive. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 88, 1191–1196 (2004).

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & Mchugh, P. R. Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12, 189–198 (1975).

Chapman, P. R. & Underwood, G. Visual search of driving situations: Danger and experience. Perception 27, 951–964 (1998).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Tim Hilts for editing this manuscript, Mr Kiyohide Tomooka (Department of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, Juntendo University) for assisting with statistical analysis of the study and Masahiko Ayaki MD, PhD (Department of Ophthalmology, Keio University School of Medicine) for assisting with the design of the study. Additionally, the authors extend the appreciation to Takuya Hiraga, CO, Yuka Fukano, CO, Emina Iwasaka, CO, for their generous cooperation in data collection. None of these persons received any compensation for their contributions.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (grant number 21K09737) and TOYOTA mobility foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors who contributed to the design and conduct of the study were S.KS.; to the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data were S.KS, T.F.; and to the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript was S.KS, T.F., M.T, A.M., K.I.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kunimatsu-Sanuki, S., Fukuchi, T., Takahashi, M. et al. Discrepancy and agreement between subjective symptoms and visual field impairment in glaucoma patients at a driving assessment clinic. Sci Rep 15, 423 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84465-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84465-2

This article is cited by

-

Usefulness of a simplified self-checking tool (Quattro Checker®) for visual field defects in glaucoma patients

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2026)

-

The association between self-checked visual field impairment and motor vehicle accidents among Japanese taxi drivers

Scientific Reports (2025)