Abstract

The current study involves the conversion of oil derived from Palm into biodiesel using a two-stage trans esterification process. The physiochemical and filterability characteristics of biodiesels are analyzed and experiments are carried out employing a single-cylinder four-stroke diesel engine to test several biodiesel blends as B0, B20, B30, and B40 for their filterability, performance, and emission characteristics. B20 had an FBT value of 1.36, and experimental outcomes were analyzed using response surface methodology optimization using Design expert software. The findings indicate that the emission characteristics and performance of the B20 blend closely resemble those of diesel fuel. At full load, the brake specific energy consumption is measured at 11.52 MJ/kW h, while the Brake thermal efficiency stands at 32.14% for the B20 blend. These values are comparable to diesel, with variations of 2.12% and 1.96% respectively. During the experiment, the emission parameters of HC, CO, and smoke were 6.12%, 17.67%, and 9.6% respectively, lower for B20 blend than diesel. Nevertheless, NOx of the biodiesel emission B20 blend is 2.03% greater than those of diesel, representing the lower than others. Furthermore, the optimization of the results of a CI engine achieved through the development of a CCD model that employs RSM. The research revealed that B20 is the most advantageous mix relative to other alternatives and functions effectively as a diesel substitute.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Energy is one of the most widely recognized essential input factors for both economic progress and personal comfort. An energy source’s accessibility is the primary determinant of a country’s economic development. Both non-renewable and renewable resources can provide energy. Energy statistics indicate that fossil fuels account for an estimated 70–80% of the world energy1. The use of fossil fuels is the only cause of almost 95% of carbon emissions worldwide today. The world is presently confronted with simultaneous predicaments of diminishing fossil fuel reserves and ecological deterioration. The Indian farming area currently has about 6.5 million diesel engines that are used for various activities. These engines consume a significant amount of diesel fuel, making it necessary to find alternate fuels quickly2,3.

The efficiency of the diesel engine ranges from 33 to 40%. The incomplete combustion of a substance results in the production of hazardous gases such as carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxides (NOx), carbon dioxide (CO2), and hydrocarbon (HC). Given the finite nature of these fuels, there is a constant need for an alternative fuel in the field of study. This alternative must meet the criteria of being cost-effective, readily accessible, highly efficient, and most crucially, renewable4. India uses third-most energy after the US and China. Additionally, India’s agriculture economy and GDP is stronger. Thus, vegetable oil is the ideal diesel fuel substitute since it behaves like petroleum diesel and can be utilized in modern diesel engines without modification5,6.

In India, the rate of increase in demand for petroleum products has outpaced the rate of increase in domestic supply. The global researchers are being urged to prioritize the development of alternative fuels for diesel engines that are technically feasible, economically competitive, environmentally acceptable, and readily available. In alignment with the substantial biofuel promotion initiative initiated by the central government at the national level, state governments are concurrently developing and implementing biofuel policies that reflect this progress. Several studies have drafted and published documents outlining their biofuel policies in accordance with the National Biofuel Policy- India is the third largest producer of oil seeds, accounting for around 20% of global production7. The planning commission states that it is possible to reclaim 35 million hectares of land by planting oil trees and producing non-edible oils from 135 million hectares of waste land in the country8,9. The Air Quality Index of the national capital has exceeded 450 on the scale, which has a maximum level of 500. The air quality index above 300 is extremely harmful to the health of the residents in that location10.

The transportation industry is the second-largest user of energy globally, following the industrial sector. It accounts for 30% of the total energy consumed. The projected annual growth rate for global transportation energy consumption between 2005 and 2035 is 1.8 percent11. Nevertheless, the anticipated decline in the use of fossil fuels and the environmental concerns linked to their usage have motivated numerous academics to explore the feasibility of employing alternative fuels12. Out of all the options, biodiesel stands out as a highly promising resource. Based on the research, the expense of feedstock alone constitutes about 75% of the whole expenditure for biodiesel manufacturing13.

Palm biodiesel is gaining interest as a possible alternative energy source since its properties are extremely similar to those of traditional diesel14. Colombia is a suitable comparative case for Malaysia regarding biodiesel development, as it is the leading producer of palm oil in Latin America and significantly contributes to the bioethanol sector15. Palm biodiesel’s 35% share of the worldwide market is largely responsible for its rise to prominence as a biofuel. The inexpensive price of 660 USD per ton, 5000 kg per hectare on high oil content, and outstanding produce output of 4.2 mT/h are main reasons for its domination16. Consistent with previous years, analysts predict that the palm oil market will reach $92.84 billion by 202117. Adding palm oil to all the test fuels evaluated resulted in lower emissions. Among the fuels tested, B20 blend maintained a consistent combustion process while minimizing emissions, making it the best performance18. Fatty acids of varying lengths linked to a glycerin molecule form trivalent long-chain alcohols; tiglycerides are essential in trans-esterification because of the charge they provide. The esterification process produces glycerine as a byproduct after breaking these bonds and re-esterifying the fatty acids with methanol to create a monovalent methyl ester of the fatty acids19,20. Ogunwa et al. have been efforts by researchers to create biodiesel by transesterifying papaya seed oil and rambutan seed oil using enzymes. To simplify operations, immobilized enzymes can be used as catalysts for downstream separation in this method, which speeds up the trans-esterification step21.

The physiochemical properties of vegetable oils, including viscosity, density, CV, flash point, fire point, and CN, were investigated22. Effective reduction of the viscosity of vegetable oils is possible via the transesterification process. The higher viscosity was attributed to the separation of glycerol from the vegetable oil during the transesterification process, as reported23. The viscosity of fuel exerts a substantial impact on the processes of liquid droplet formation, vaporization, atomization, and air–fuel mixture formation, thereby influencing diesel engine performance parameters and exhaust emission. Among other greater percentages of palm oil mixtures, the one with 20% diesel was the most desirable. Compared to diesel, this mixture slight increase in NOx emissions while decreasing CO and HC emissions24,25.

The possibility of filter blockage increases as the proportion of biodiesel to diesel increases. Fuel blend concentration and the maximum time a filter obstructed were evaluated using FBT. It was mentioned that biodiesel and diesel mixtures might clog filters due to sterol glucosides26. The inclusion of FSG compounds, in particular, degrades biodiesel quality as fuel temperature increases. On the other hand, FBT seems reliable and stringent method for guaranteeing vehicle operation in cold flow properties than CFPP and CP27. Biodiesel and diesel mixes could clog filters due to sterol glucosides. Because biodiesel contains both water and alcohol in higher concentrations, it weakens the tensile strength of the filter medium. When immersed in WCO and Karanja biodiesel, the tensile strength was reduced28. Up to 42% less cloud point and CFPP was produced when palm biodiesel was blended with 30% methyl oleate. Blockages in gasoline lines and filters can be caused by fuel solidification, which can be caused by poor mix property values. The physical characteristics and cold flow of biodiesel are greatly impacted by its content29. In their evaluation of engine performance and emissions in city driving conditions, Giakoumis and Alafouzos has highlighted the importance of load changes in emissions under these situations30. The best Palm oil combination was 20% Palm oil and 80% diesel. This fuel mixture decreases CO and HC emissions but boosts NOx more than diesel31.

During the course of this research, the objective is to lessen reliance on fossil fuels while simultaneously encouraging the progress of biofuel as alternates. This research focus comprehensively evaluates palm biodiesel blends (B20–B40) through both experimental and statistical (RSM-based) approaches, targeting combustion, performance, and emissions, an integrated analysis that is rarely covered together in the existing literature. The innovative aspect lies in combining experimental engine trials with optimization using Response surface methodology. Also, this study examines the processed biodiesel obtained from Palm oil, as well as the engine characteristics of test fuels powered by palm biodiesel/diesel blends. Furthermore, assessing the physicochemical characteristics of palm biodiesel blends and contrasting them with diesel. The optimum proportion of test blend was determined using this study’s regression model, which was based on numerical analysis of response surface approach.

Materials and methods

Preparation of biodiesel

Palm oil is produced by harvesting and processing fruit bunches. Prior to mechanical stripping, the fruits undergo sterilization to inactivate enzymes. The palm fruits are thereafter forced into pressing in order to obtain the palm oil, which is then separated from the palm kernel oil. The raw palm oil undergoes refining process like degumming, bleaching, and deodorizing to yield edible palm oil that is suited for engines. As seen in Fig. 1, before oil extraction, the seeds are retrieved from fully developed pods, usually as they start to dry up and become brown. After that, the seeds are carefully dried to remove any excess moisture and cleaned to remove any debris. Once the seeds have dried, they can be ground or processed to extract their oil. The schematic diagram of oil extraction methods as shown in Fig. 1.

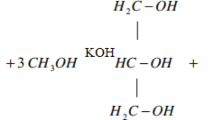

A transesterification reaction was employed to obtain the biodiesel as shown in Fig. 2. The chemical reaction of alcohol with triglycerides i.e., the fats of oils, in the presence of a catalyst is called the transesterification reaction. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and potassium hydroxide (KOH) are examples of homogeneous bases that act as catalysts which allows possible reaction of triglycerides derived from oils with alcohols like methanol. As acid catalysts, sulfuric acid and acidic ionic liquids are rare. In order to improve the conversion of triglycerides, a mixture of sodium hydroxide and methanol was used to convert gulmohar seed oil into biodiesel and Fig. 3 Shows the chemical reaction of the transesterification process. In order to produce diglycerides, monoglycerides, and glycerol, the procedure has three reversible steps. FAME is the major molecular components of biodiesel, were made at each stage. The Physicochemical properties of test fuels as shown in Table 1.

Engine specification

To study the impact of palm biodiesel blends in the single cylinder four stroke CI engine coupled with eddy current dynamometer was used to assess its characteristics. Pressure data from the injector and cylinder head sensors were used by the "IC engine soft" program to evaluate its performance and combustion. Encoder measured the crank angles. AVL DI GAS 444N (Five Gas Analyzer) measured the CO, HC, and NOx. AVL 437C Smoke meter examined the smoke opacity. The schematic diagram of the test engine is given in Fig. 4. Engine and equipment specifications were reported in Tables 2 and 3.

Experimental design and optimization

After obtaining the experimental dataset, numerical modelling is implemented using the RSM technique. The best way to find the result values was using the experimental data that the numerical model produced. By reducing the number of RSM trials, we may more easily select the input variables that will yield the desired results from our experiments. The study parameters must have their lowest and maximum values determined. Numerous input parameters are required of diesel engines. The time and effort needed to examine the interplay of various input variables is substantial. In the context of physical testing, reducing time and money spent on optimisation can improve the RSM’s efficacy. The penultimate stage of RSM is to apply numerical optimisation methods. The optimisation procedure makes it simpler to discover the most advantageous independent variables by adjusting the responding variables to satisfy the set criteria. Focusing on the parameters under investigation, the experiments collect data using measures that are suitable for the enquiry. After determining the dependent and independent variables, this study’s methodology was developed and result data was generated. All other parameters are constant, the proposed experiment sets will be executed using the given input parameters. The RSM process structure is illustrated in Fig. 4. Using Design Expert-13 and the CCD approach, the study team developed a DOE for testing. Using the RSM framework, the study determined the optimal operating settings by analysing two critical variables: load (L) and coating thickness (µm)32.

Analysis and modelling

In order to examine the impact of load and coating thickness, the CCD used a technique that included 30 runs. In order to determine how well the model worked, we had to compare the predicted level of engine characteristics with the actual results. Load and coating thickness were the input elements chosen, and performance, combustion and emission parameters were the output variables for engine characteristics. Figure 5 depicts the RSM process structure and Eq. 1 shows the input items being analyzed using RSM with a quadratic model.

The DFA, a method with many practical uses, is employed to optimize the regression equations of the multiple RSM models. A non-dimensional variable called the desirability (Pi) value is generated by summing together all of the output replies. An integer between zero and one is a pi number. When the response variable reaches its intended or target values, it approaches 1. The desirability rating becomes close to zero when the answer falls below the allowed threshold. Any possible aim, maximum, minimum, between, or equal to outcome might be offered in the challenge. Furthermore, we provide an Eq. (2) for the calculation of total desirability (P). The optimal test fuel mixtures were estimated using the desirability function, which was created in RSM.

Uncertainty analysis

The reliability of the research has been assured through the implementation of error analysis. The percentage of inaccuracy for the test engine, gas analyzer, and emission meter was determined. The total uncertainty was evaluated using the square root method.

Result and discussion

FBT

The variations of FBT for test fuels are shown in Fig. 6. Biodiesel blends filterability measure as B0, B20, B30, B40 were 1.01, 1.38, 2.5, and 3.7 respectively. The raw biodiesel B100 demonstrated an FBT value of 24, exceeding the stipulated operating standards. Nevertheless, elevated mixes must still comply with the FBT criteria. The increased concentration of biodiesel affected viscosity by changes in viscosity and density33. This investigation indicated that test fuel blend B20 has a value of 1.38, which conforms to the ASTM standard (D2068-14). Conversely, elevated mixes failed to satisfy the filterability criteria. Notable variability results are observed, and byproducts were associated with clogging problems. The FBT value ranged from 22 to 30 for B100 derived from various feedstocks34.

Brake specific energy consumption

The most suitable parameter for comparing fuels with varying CVs is brake specific energy consumption (BSEC). Multiplying the BSFC by the calorific value of the fuel yielded the BSEC. Results showed that there was an influence of fuel pump volume on brake-specific energy consumption and that there was a correlation between mix coefficient of variation and engine fuel pump volume35. The lower mass and CV of biodiesel can be ascribed to its increased energy consumption in comparison to diesel36. However, the CV was reduced; however, the higher oxygen concentration and viscosity balanced for this. The reduced heating value of biodiesel compared to diesel causes BSEC to increase by a max. 14.04 MJ/kWh for B100 at full load (Fig. 7). B20 blend has lowest specific energy consumption recorded at maximum load was 11.52 MJ/kWh; this was raised by 2.12% of the diesel. Similar result shows, Rajpoot et al., compared the palm with Jatropha, and microalgae biodiesel operating at loads less than 40%, B20’s BSEC exceeded that of diesel37.

Brake thermal efficiency

Figure 8 shows how the BTE changes with different diesel to biodiesel ratios as the engine load increases. A rapid increase in BTE was observed in all of the test blends at 75% load, with a modest additional increase at full load. The high viscosity and low heating value of all test fuels resulted in a lower BTE than undiluted diesel. Nevertheless, the B20 blend exhibited the higher BTE among all the blends, albeit 2% lower than diesel. The temperature in the combustion zone rose with the rise in load, which enhanced the evaporation of biodiesel blends and led to greater BTE24. An increase in the CN of biodiesel led to an earlier discharge of heat energy during combustion. Furthermore, the thermal efficacy of brakes was enhanced by the use of biodiesel with elevated levels of saturated fatty acids38. The elevated oxygen content in biodiesel leads to improved power output, reduced thermal loss, and increased combustion efficiency relative to diesel39.

Heat release rate

The measurement of heat release rate (HRR) for Palm biodiesel blends (B20, B30, B40) and diesel in a compression ignition (CI) engine elucidates combustion properties. The HRR denotes the rate of energy release during combustion, influencing engine efficiency and emissions. In Palm biodiesel blends, the heat release rate (HRR) typically occurs earlier than in diesel, due to the higher cetane number and oxygen concentration that improve ignition characteristics40. Figure 9 shows the blend ratio increases from B20 to B40, the peak heat release rate (HRR) exhibits a slight decrease, indicating of reduced combustion rates attributable to the high viscosity and lower volatility of biodiesel. Biodiesel blends demonstrate an extended combustion period relative to pure diesel, resulting in a consistent energy release and potentially reduced peak cylinder pressures41.

Ignition delay

Ignition delay denotes the duration between the initiation of fuel injection and the beginning of combustion in a compression ignition (CI) engine. In palm biodiesel blends like B20, B30, and B40, ignition delay is generally reduced relative to regular diesel fuel owing to the higher cetane number of biodiesel as depicted Fig. 10. Increased cetane levels enhance fuel reactivity and shorten the ignition delay period. As the concentration of biodiesel in the blend increases, both viscosity and density increase, potentially affecting fuel atomization and air–fuel mixing, which may significantly prolong the ignition delay. However, pure diesel typically exhibits a prolonged ignition delay as a result of its lower Cetane number in comparison to biodiesel blends42. The ignition delay for biodiesel blend is also subject to variation based on engine operating conditions, including load, speed, and temperature. It tends to decrease as engine temperatures and injection pressures increase, which leads to improved combustion characteristics43.

CO emission

Low flame temperature and insufficient oxygen in the air–fuel mixture caused diesel engine CO emissions. The graph indicated that CO emission was marginally higher at dormant (no load) conditions The CO emission for diesel, B20, B30, and B40 were recorded at maximum load conditions at 8.94, 7.36, 7.04, and 6.79 g/kWh respectively. CO emission is reduced to a minimum at part capacity as the load increases. A rich fuel mixture and an abbreviated ID resulted in insufficient oxidation, which led to an increase in CO emission at higher loads44. Figure 11 illustrates that diesel fuel emits 8.94 g/kWh of CO, which was perceived as higher than that of other test fuels as a result of insufficient oxidation. The use of a B20 blend in place of diesel can result in a significant reduction of 17.67% in CO emission. The environment and pollution control are both benefited by this reduction in CO emission. Bannister et al.45 reveals the combustion of biodiesel may result in CO2 generation from an extra oxygen content. This procedure contributes to the reduction of CO2 emission. When the engine’s power is low, the combustion rate is delayed, and the air–fuel ratio is high, all of which lead to increased CO emissions46. The combustion chamber is injected with a greater quantity of fuel when the engine is operating at optimum capacity, resulting more affluent fuel zones. Engine speed and petrol temperature increase resulting increased air-to-fuel ratio, which results in an increase in CO 47.

NOx emission

Figure 12 shows how engine load and blend ratios affect NOx emission in the test engine. The NOx emission at full load conditions for B0 (diesel), B20, B30, and B40 were 5.79, 5.91, 6.08, and 6.19 g/kWh, respectively. The additional oxygen in biodiesel and its blends resulted in an increased NOx for tested blends than diesel. The formation of NOx can be facilitated by increased oxygen levels. B20 is 2.03% more than diesel and has a lower NOx content than all other biodiesel and its blends. The highest level of NOx emission was observed during the maximal load condition, as a result of the increased heat release, which corresponded to an increase in NOx emission48,49. In general, diesel engines emit fewer NOx emission than biodiesel due to their reduced oxygen content. The use of biodiesel frequently results in elevated NOx in the exhaust as a consequence of its heightened CV, reduced ID, and higher CN50. The increased temperatures that occur when the combustion process comes to a close are responsible for the increase in NOx emissions51.

HC emission

Figure 13 illustrates the impact of HC emission on various engine conditions. The HC emission values for B0 (diesel), B20, B30, and B40, at 100% load are 0.147, 0.138, 0.136, and 0.130 g/kWh respectively. The data collected showed that the HC emission of the blend B20 was 6.12% lower than that of the diesel fuel. The biodiesel mixed test fuels reduced HC emissions due to their greater CN and oxygen content. Some research finding reveals the reduction of HC emission is facilitated by a higher CN and a greater concentration of oxygen in the fuel. The combustion process is facilitated by oxygen, while a higher CN reduces the ID52. A substantial reduction in HC emission was observed as the concentration of biodiesel increased.

Smoke opacity

The test engine’s smoke opacity varied with load and different biodiesel mixes, as seen in Fig. 14. Palm has increased oxygen content and the lack of aromatics in the biodiesel blend, B20 has a 9.6 percent lower smoke opacity than diesel. While oxygenated fuels speed up the combustion process and oxidise soot precursors, palm biodiesel’s low aromaticity reduces the production of smoke-inducing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Combustion is made cleaner and particle emissions are lowered as a result of these combined effects. A major factor affecting the oxygen concentration in fuel mixes was the smoke opacity, which was a measurement of the overall quantity on smoke-opacity expelled in exhaust. Nitrogen and oxygen react chemically at elevated combustion temperatures. Due to oxygen deficiency, partial combustion happens under full load circumstances53. The fuel-rich area of the cylinder is where smoke is produced due to the circumstances of high temperature and pressure54. Diesel, on the other hand, produces a great deal of smoke since oxygen is not present. The longer the ID, the more time is needed to premix the fuel and air before combustion begins, which in turn promotes55.

Optimization of engine outcomes using RSM

The analysis of correlation with independent variable affecting engine reactions are conducted using the CCD. Surface plot construction, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and regression (R2) were among the computational methods employed for this work. The primary objective of phase to establish advantageous conditions for CI engine reactions. This study employed two primary variables, engine load and biodiesel blend, within the context of RSM to identify the optimal operating parameters. Table 4 displays the factors and levels of the response variables.

A comparison between the expected and actual values is used to assess the RSM model. Tables 5 and 6 display the investigational data along with the anticipated values of the response and RSM. The regression models for all of the response variables in Table 7. The RSM-based regression analysis shows that the experimental circumstances were well-represented in the expected behavior of the hydrogen percentage. Using analysis of variance (ANOVA), this study assessed the suggested models’ efficacy and controlled for the most important variables. To build a regression model of the engine’s reactions, Table 8 displays the ANOVA findings. The relevance of each variable was determined using these data. The results showed that the engine responses had regression values that were statistically significant. The modified R-squared value describes the effect of the hydrogen fraction on the efficiency of biodiesel power plants and gives proof that the correlation coefficients are genuine. Acceptable matches were defined in a prior research of R2 analysis as models with an R2 value higher than 0.856. When the collected data was fitted using a quadratic model, the correlation was strongest, and the standard deviation was quite minimal. R2 is a measure of the model’s fit to the data; it is also called the coefficient of determination. R2 is a statistical metric that evaluates how well a regression model’s predictions match up with the real data. The study also discovered much higher R2 values, which means the model was well-fit and could predict the answers with some degree of certainty. Many data values close to follow the linear, as illustrated in probability plot in Fig. 15, which highlight on accuracy in predicting experiment value. The contour graphs show how the performance and emission characteristics of the test mixes are expected to respond. Evidence suggests that a biodiesel blend percentage of between 75 and 20% with diesel is the optimum parameters with desirability value 97% and Table 9 presents the relative error between experimental and predicted outcomes.

Conclusion

This study set out to evaluate the Kirloskar TV1 four-stroke diesel engine in terms of its efficiency and emission levels, when operated on a blend of biodiesel and diesel at varying ratios with a focus on optimizing parameters using RSM. The key findings are summarized as follows:

-

Among the tested blends, B20 demonstrated optimal performance, with a brake thermal efficiency (BTE) of 32.14%, is 1.96% lower than diesel, and brake specific energy consumption (BSEC) of 11.52 MJ/kWh, is 2.12% higher than diesel, indicating good thermal efficiency and fuel utilization.

-

Emission analysis showed that B20 reduced HC, CO, and smoke emissions by 6.12%, 17.67%, and 9.6%, respectively, compared to diesel. Although NOx emissions increased by 2.03%, B20 exhibited the lowest NOx levels among all biodiesel blends.

-

The RSM-based regression models demonstrated high reliability (R2 > 0.99), confirming the accuracy of the model in predicting engine response variables. The optimization results identified B20 at 75% load as the most desirable combination, with a desirability score of 0.97.

Scope of future work

This study offers insights for engine designers to identify optimal biodiesel blend ratios and operating conditions. While B20 showed promising performance, future work should explore biodiesel reformulation strategies to reduce NOx emissions without affecting other parameters. Additionally, extended-duration engine tests are recommended to evaluate long-term impacts on wear, deposits, and emission stability. These efforts will help validate the real-world applicability and sustainability of palm biodiesel blends in diesel engines for long-term, practical use.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BSFC:

-

Brake specific fuel consumption

- BTE:

-

Brake thermal efficiency

- CI:

-

Compression ignition

- CN:

-

Cetane number

- CO:

-

Carbon monoxide

- CP:

-

Cylinder pressure

- FIP:

-

Fuel injection parameters

- HC:

-

Hydrocarbon

- HRR:

-

Heat release rate

- IC:

-

Internal combustion

- ID:

-

Ignition delay

- NOx:

-

Oxides of nitrogen

References

Rajpoot, A. S., Choudhary, T., Chauhan, A. K., Pachori, H. & Sharma, M. Thermal and emission analysis of waste plastic and microalgae biodiesel as a potential power source for diesel engines: A sustainable approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 59961–59976 (2024).

Akhdar, A. et al. Thermomorphic polyethylene‐supported organocatalysts for the valorization of vegetable oils and CO2. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 5 (2021).

Srinidhi, C., Madhusudhan, A. & Channapattana, S. V. Effect of NiO nanoparticles on performance and emission characteristics at various injection timings using biodiesel-diesel blends. Fuel 235, 185–193 (2019).

Lou, G., Ma, H., Fan, T. & Chan, H. K. Impact of the dual-credit policy on improvements in fuel economy and the production of internal combustion engine vehicles. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 156, 104712 (2020).

Musthafa, B. et al. Performance and emission analysis of a diesel engine fuelled with Juliflora biodiesel: a simulation and experimental study. Aust. J. Mech. Eng. (2023) https://doi.org/10.1080/14484846.2023.2274999.

Soni, N. et al. Advancing sustainable energy: Exploring new frontiers and opportunities in the green transition. Adv. Sustain. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1002/adsu.202400160 (2024).

Musthafa, B. & Asokan, M. Reducing NOx emission from palm biodiesel/diesel blends in CI engine: A comparative study of cetane improvement techniques through hydrogenation and fuel additives. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J Process. Mech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544089231223380 (2024).

Dwivedi, S. et al. Reactive oxygen species mediated bacterial biofilm inhibition via zinc oxide nanoparticles and their statistical determination. PLoS ONE 9, e111289 (2014).

Cirujano, F. G. & Dhakshinamoorthy, A. Engineering of active sites in metal–organic frameworks for biodiesel production. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 5 (2021).

Srinidhi, C., Madhusudhan, A., Channapattana, S. V., Gawali, S. V. & Aithal, K. RSM based parameter optimization of CI engine fuelled with nickel oxide dosed Azadirachta indica methyl ester. Energy 234, 121282 (2021).

Channapattana, S. V. et al. Energy analysis of DI-CI engine with nickel oxide nanoparticle added azadirachta indica biofuel at different static injection timing based on exergy. Energy 267, 126622 (2023).

Kumar, H., Sarma, A. K. & Kumar, P. Experimental investigation of 2-EHN effects upon CI engine attributes fuelled with used cooking oil-based hybrid microemulsion biofuel. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19, 11051–11068 (2022).

Rajpoot, A. S., Choudhary, T., Chelladurai, H. M., Rajak, U. & Sinha, A. A. Effect of oxy hydrogen (HHO) gas on energy, exergy, and sustainability analysis of a diesel engine fueled with palm oil biodiesel. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process. Mech. Eng. 15, 152. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544089241259758 (2024).

Tiwari, C., Dwivedi, G. & Verma, T. N. Sustainability evaluation, optimization and research dynamics of microalgae methyl ester in a research diesel engine. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process. Mech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544089231162318 (2023).

Yusoff, M. N. A. M. et al. Sustainability of palm biodiesel in transportation: A review on biofuel standard, policy and international collaboration between Malaysia and Colombia. BioEnergy Res. 14, 43–60 (2021).

Kumar, H., Sarma, A. K. & Kumar, P. A comprehensive review on preparation, characterization, and combustion characteristics of microemulsion based hybrid biofuels. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 117, 109498 (2020).

Dey, S., Reang, N. M., Das, P. K. & Deb, M. A comprehensive study on prospects of economy, environment, and efficiency of palm oil biodiesel as a renewable fuel. J. Clean. Prod. 286, 124981 (2021).

Sivakrishna, T., Madhu, S. & Sivakumar, K. The effect of palm biodiesel fuel on the performance of automotive four stroke diesel engine. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 574, 012015 (2019).

Kesharvani, S., Dwivedi, G., Verma, T. N. & Verma, P. The experimental investigation of a diesel engine using ternary blends of algae biodiesel, ethanol and diesel fuels. Energies 16, 229 (2022).

Kumar, H., Sarma, A. K. & Kumar, P. A novel approach to study the effect of cetane improver on performance, combustion and emission characteristics of a CI engine fuelled with E20 (diesel—bioethanol) blend. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 14, 100185 (2019).

Ogunwa, K. I., Ofodile, S. & Achugasim, O. feasibility study of melon seed oil as a source of biodiesel. J. Power Energy Eng. 03, 24–27 (2015).

Ferella, F., Mazziotti Di Celso, G., De Michelis, I., Stanisci, V. & Vegliò, F. Optimization of the transesterification reaction in biodiesel production. Fuel 89, 36–42 (2010).

Musthafa, B. & Asokan, M. A. Numerical and experimental investigation of performance and emission characteristics of hydrogen enrichment with prosopis juliflora biodiesel in CI engine using RSM and ANN optimization. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 66, 326–336 (2024).

Senthur Prabu, S., Asokan, M. A., Prathiba, S., Ahmed, S. & Puthean, G. Effect of additives on performance, combustion and emission behavior of preheated palm oil/diesel blends in DI diesel engine. Renew. Energy 122, 196–205 (2018).

Pullagura, G. et al. Enhancing performance characteristics of biodiesel-alcohol/diesel blends with hydrogen and graphene nanoplatelets in a diesel engine. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 50, 1020–1034 (2024).

Komariah, L. N., Hadiah, F., Aprianjaya, F. & Nevriadi, F. Biodiesel effects on fuel filter; assessment of clogging characteristics. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1095 (2018).

Barba, J., Lapuerta, M., Cardeño, F. & Hernández, J. J. Are cold filter plugging point and cloud point reliable enough to prevent cold-start operability problems in vehicles using biodiesel blends?. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 234, 2305–2311 (2020).

Thangamani, S., Sundaresan, S. N., Kannappan, S. S., Barawkar, V. T. & Jeyaseelan, T. Impact of biodiesel and diesel blends on the fuel filter: A combined experimental and simulation study. Energy 227, 120526 (2021).

Das, K. et al. Improvement in cold flow properties of diesel fuel by changing its composition: A case study. Pet. Sci. Technol. 41, 665–676 (2023).

Giakoumis, E. G. & Alafouzos, A. I. Study of diesel engine performance and emissions during a transient cycle applying an engine mapping-based methodology. Appl. Energy 87, 1358–1365 (2010).

Behera, B. N. & Hotta, T. K. Experimental studies on performance and emission measures of a 4-stroke compression ignition engine using palm bio-diesel blended with N-butanol. J. Eng. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jer.2023.07.010 (2023).

Shenbagamuthuraman, V. & Kasianantham, N. Microwave irradiation pretreated fermentation of bioethanol production from Chlorella vulgaris biomasses: Comparative analysis of response surface methodology and artificial neural network techniques. Bioresour. Technol. 390, 129867 (2023).

Komariah, L. N., Hadiah, F., Aprianjaya, F. & Nevriadi, F. Biodiesel effects on fuel filter; assessment of clogging characteristics. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1095, 012017 (2018).

Haupt, J., Fischer, J., Witt, K. & Wilharm, T. Steryl glycosides and acylated steryl glycosides in vegetable oils and fatty acid methyl esters—Effects on the filterability of biodiesel. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Qual. Biodiesel e.V. (2011).

Musthafa, B. & Asokan, M. An experimental evaluation of cetane improving techniques for enhancing the performance and emission trade-off in diesel engine: A comparative study. Energy Environ. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958305X231193866 (2023).

Lapuerta, M., Rodríguez-Fernández, J. & Agudelo, J. R. Diesel particulate emissions from used cooking oil biodiesel. Bioresour. Technol. 99, 731–740 (2008).

Singh Rajpoot, A., Choudhary, T., Chelladurai, H., Mishra, S. & Shende, V. Performance analysis of a CI engine powered by different generations of biodiesel; Palm oil, Jatropha, and microalgae. Mater. Today Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.02.037 (2023).

Karthi Vinith, K. S., Soundar, A., Mahalingam, S., Sujai, S. & Guru Prasad, P. K. Experimental investigation for the usage of diesel—Jatropha—rice bran biodiesel mixture blends in four stroke diesel engine. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1055, 012067 (2021).

Bahari, R., Shafaghat, R., Jahanian, O. & Ghaedi, A. The influence of biodiesel with high saturated fatty acids on the performance of a CI engine fuelled by diesel and biodiesel blend fuels at low loads. Int. J. Ambient Energy 43, 7643–7656 (2022).

Kumar, C. B. & Lata, D. B. Effect of di-tert butyl peroxide (DTBP) on combustion parameters and NOx in dual fuel diesel engine with hydrogen as a secondary fuel. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46, 4507–4525 (2021).

Srinidhi, C. et al. A comparative performance and emission investigation CI engine fuelled with neem oil esters with varying engine compression ratios. Heat Transf. 51, 7990–8004 (2022).

Goto, S. & Lee, D. SAE TECHNICAL development of an LPG DI diesel engine using cetane number enhancing additives (2018).

Sharma, P. et al. Experimental investigations on efficiency and instability of combustion process in a diesel engine fueled with ternary blends of hydrogen peroxide additive/biodiesel/diesel. Energy Sources Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 44, 5929–5950 (2022).

Saravanan, B., Musthafa, B. & Asokan, M. A. A combined study of filterability and soaking strength of fuel filter and effect of injection timing on CI engine characteristics using Ceiba pentandra biodiesel. Biofuels 1–9 (2023).

Bannister, C. D. et al. The impact of biodiesel blend ratio on vehicle performance and emissions. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 224, 405–421 (2010).

Srinidhi, C., Madhusudhan, A. & Channapattana, S. V. Parametric studies of CI engine at various injection strategies using biodiesel blended nanoparticles as fuel. Int. J. Ambient Energy 43, 117–127 (2022).

Altarazi, Y. S. M. et al. A review of engine performance and emissions using single and dual biodiesel fuels: Research paths, challenges, motivations and recommendations. Fuel 326, 125072 (2022).

Reşitoğlu, İA., Altinişik, K. & Keskin, A. The pollutant emissions from diesel-engine vehicles and exhaust aftertreatment systems. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 17, 15–27 (2015).

Kumar, H. & Kumar, H. Microemulsification-based hybrid oxygenated biofuel for CI engine locomotives: With special reference to “preparation” techniques and “performance” analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-025-35960-0 (2025).

Saravanan, B., Musthafa, B. & Asokan, M. Assessment of CI engine vibration at various injection timing and injection pressure with Ceiba pentandra biodiesel. Int. J. Green Energy https://doi.org/10.1080/15435075.2023.2211131 (2023).

Asokan, M. A. et al. Emission and performance behaviour of flax seed oil biodiesel/diesel blends in DI diesel engine. Mater. Today Proc. 46, 8148–8152 (2021).

Jain, A. et al. Impact of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles addition in Eichhornia crassipes biodiesel used to fuel compression ignition engine at variable injection pressure. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 49, 103295 (2023).

Singh, N., Kumar, H., Jha, M. K. & Sarma, A. K. Complete heat balance, performance, and emission evaluation of a CI engine fueled with Mesua ferrea methyl and ethyl ester’s blends with petrodiesel. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 122, 907–916 (2015).

Sathish, T. et al. Waste to fuel: Synergetic effect of hybrid nanoparticle usage for the improvement of CI engine characteristics fuelled with waste fish oils. Energy 275, 127397 (2023).

Aguado-Deblas, L. et al. Biofuels from diethyl carbonate and vegetable oils for use in triple blends with diesel fuel: Effect on performance and smoke emissions of a diesel engine. Energies 13, 1–15 (2020).

Guan, X. & Yao, H. Optimization of viscozyme L-assisted extraction of oat bran protein using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 106, 345–351 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors are acknowledge the Centre for Alternate fuels Research Lab, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology, VMRF (DU), Chennai for providing facilities for our Research work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors are contributed equally on this research work and Manuscript Preparation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Musthafa, B., Prabhahar, M. Numerical and experimental investigation of CI engine parameters using palm biodiesel with diesel blends. Sci Rep 15, 43399 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00170-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00170-8