Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of medical staff regarding the prevention of unintentional perioperative hypothermia. This multicenter cross-sectional study enrolled medical staffs in northern China between September and November 2022. A total of 213 valid questionnaires were collected. The mean scores for knowledge, attitudes, and practices were 5.36 ± 2.06 (total score of 12), 47.54 ± 5.44 (total score of 55), and 31.57 ± 4.37 (total score of 40), respectively. The participant demographics included 14 surgeons (6.57%), 29 anesthesiologists (13.62%), and 170 operating room nurses (79.81%). Significant differences were observed in the knowledge (P = 0.046) and practices (P = 0.023) related to perioperative hypothermia among surgeons, anesthesiologists, and operating room nurses. Pearson correlation analysis revealed positive correlations between knowledge and attitudes (r = 0.21, P = 0.002), knowledge and practices (r = 0.23, P = 0.001), as well as attitudes and practices (r = 0.57, P < 0.001). Structural equation modeling indicated that knowledge had a direct effect on attitudes (β = 0.56, P = 0.002) and an indirect effect on practices (β = 0.25, P = 0.003). Additionally, attitudes had a direct effect on practices (β = 0.45, P < 0.001). This study concluded that knowledge regarding the prevention of unintentional perioperative hypothermia was inadequate; however, most participants exhibited a positive attitude and acceptable practices. Targeted interventions are necessary to enhance understanding and implementation in clinical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perioperative hypothermia, defined as a core temperature below 36 °C during surgery, except in cases of therapeutic hypothermia1, is a common occurrence affecting 20–70% of patients during the perioperative period2. Contributing factors include the operating room environment, anesthesia, blood transfusions, and prolonged exposure of body parts3,4. Perioperative hypothermia is closely associated with various postoperative complications, such as surgical site infection (SSI), coagulation dysfunction, slowed drug metabolism, increased cardiovascular events, and prolonged hospital stay, which is detrimental to the patient’s postoperative recovery5,6,7. Studies have shown that medical and nursing staff implementing measures to maintain patients’ body temperature in the operating room would minimize intraoperative and postoperative hypothermia8, thus reducing postoperative complications5,6. Prewarming was proven to be one of the most cost-effective measures in reducing inadvertent intraoperative hypothermia8,9. Therefore, some perioperative hypothermia could be avoided by reminding medical staffs in the operating room, such as nurses, surgeons and anesthesiologists to apply heat preservation measures effectively.

The knowledge, attitude, practice (KAP) study was generally used to understand the KAP of the target population in health care10. A survey of six Asia-Pacific countries (Singapore, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, India, and South Korea) revealed that anesthesiologists’ and anesthesia trainees’ compliance with perioperative temperature management guidelines remained poor, especially in small hospitals11. Many countries have issued evidence-based clinical guidelines and recommendations for the importance of maintaining perioperative normothermia12,13,14. Subsequently, some questionnaire-based studies were conducted to investigate healthcare providers’ knowledge of perioperative hypothermia and adherence to the guidelines. However, there are few studies in China. The Chinese healthcare system delivers care to a large population that is characterized by wide disparities among provinces and cities and between urban and rural settings15.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the KAP of medical staffs in the operating room, such as nurses, surgeons and anesthesiologists towards perioperative temperature prevention. Specifically, the study sought to identify gaps in knowledge, variations in attitude, and differences in practice across professional roles, with the objective of providing evidence to support targeted educational interventions and standardized heat preservation protocols. This research highlights the critical role of multidisciplinary collaboration in reducing perioperative hypothermia and associated complications, addressing an important clinical issue in patient safety.

Methods

Study design and participants

This multicenter cross-sectional study enrolled physicians and nurses in north China between September and November 2022 using a convenience sampling method. Inclusion criteria were surgeons, anesthetists, and operating room nurses with more than one year of working experience. The exclusion criteria were interns. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Shijitan Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University [Sjtky11-1x-2023(004)]. Informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Questionnaire and data collection

This study designed a structured questionnaire with reference to the Chinese expert consensus on the management of perioperative hypothermia14and relevant guidelines from other countries16,17. The draft was revised based on the comments put forward by a clinical nursing specialist and an anesthesiologist.

The questionnaire’s construct validity was assessed through exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure was used to verify sampling adequacy for factor analysis. Principal component analysis with orthogonal varimax rotation was employed to examine the factor structure. Factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were retained, and items with factor loadings ≥ 0.40 were considered significant. The reliability and convergent validity of the questionnaire were further assessed using McDonald’s omega (ω) and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE). Detailed results of these analyses, including omega and AVE values, are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. Thirty-two questionnaires were distributed for the pretest, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.750, indicating good reliability. The final questionnaire was in Chinese and constituted four sections with 44 items (10 items in basic information, 12 in knowledge, 11 in attitude, and 10 in practice section). For the knowledge items, one point was given for each correct answer, while no points were given for incorrect or ‘don’t know’ answers. The knowledge scores ranged from 0 to 12. Attitude was assessed using eight questions using a 5-point Likert scale, graded from strongly agree (5 points) to strongly disagree (1 points). The attitude scores ranged from 11 to 55. The practice dimension encompasses 5 questions with a total of 11 items, also utilizing a five-point Likert scale, and scores range from 8 to 40 points based on responses ranging from very positive (5 points) to very negative (1 point). The descriptive analysis was carried out on the 9–10 questions. For each dimension, a cumulative score exceeding 80% is regarded as indicative of adequate knowledge, a positive attitude, and proactive Practice.

Questionnaire distribution and quality control

The hospitals selected for this study are primarily located in Beijing and Shandong, including Beijing Chao-yang Hospital, Capital Medical University; Beijing Shijitan Hospital, Capital Medical University; Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital; Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University; China-Japan Friendship Hospital; Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University; Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University; and The Affiliated Qingdao Third People’s Hospital of Qingdao University. Using convenience sampling, we recruited eligible participants including surgeons, anesthetists, and operating room nurses with more than one year of experience. Each hospital appointed an executive who coordinated the survey locally. The executives were responsible for identifying and approaching potential participants based on their availability and willingness to participate. Researchers communicated the study’s purpose and the principle of anonymity to the executives, who then disseminated this information to the participants. The executives distributed the electronic questionnaire with a consent page to all eligible physicians and nurses in their respective hospitals. Participation was voluntary, and staff who agreed to participate completed the survey. The convenience sampling method ensured that participants were readily accessible and willing to contribute within the study timeframe.

Statistical analysis

Ideally, the sample size should be a minimum of 5–10 times the number of predictors. Given that this questionnaire includes 33 independent variables, the required minimum sample size would be 165. To account for potential non-responses, typically estimated at 20%, the final necessary sample size would need to be adjusted to 207 participants.

The data was analyzed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire, and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure was employed to evaluate the adequacy of the sampling for factor analysis. All continuous variables were normally distributed and presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables were presented as frequency (percentage). Pearson’s correlation analysis estimated correlations between knowledge, attitude, and practice. In multivariate analysis, 80% of the total score was used as the cut-off value. Univariate variables with P < 0.05 were enrolled in multivariate regression. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was utilized to test the hypotheses that (1) knowledge affects attitude, (2) knowledge affects practice, and (3) attitude affects practice. The fit of the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was assessed using the following indices: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). In addition, a subgroup analysis was done for the group of nurses among the participants. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered a significant difference.

Results

Questionnaire validation

The KMO value was 0.845 (P < 0.001), indicating excellent sampling adequacy for factor analysis. EFA identified three factors explaining 38.93% of the total variance (Factor 1: 21.52%, Factor 2: 9.60%, Factor 3: 7.81%). After varimax rotation, Factor 1 primarily represented attitude items with loadings ranging from 0.73 to 0.81, Factor 2 mainly captured practice items with loadings between 0.48 and 0.81, and Factor 3 predominantly reflected knowledge items with loadings from 0.41 to 0.52. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.820 demonstrated good internal consistency reliability.

Demographic characteristics

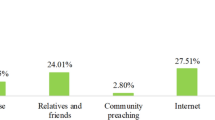

A total of 215 questionnaires were collected. All questionnaires were verified, and 2 of them were excluded due to incomplete filling. Therefore, 213 questionnaires were finally included, with a validity rate of 99.07%. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.820, indicating good reliability, and the KMO value was 0.845 (P < 0.001), suggesting that the data is suitable for factor analysis. Most participants were female (73.71%), and 102 (47.89%) were 31–40 years of age. There were 170 (79.81%) nurses, 29 (13.62%) anesthetists, 14 (6.57%) surgeons, 86 (40.38%) with junior titles, and 98 (46.01%) intermediate titles. Most participants in this study worked in public tertiary hospitals (82.63%), and 190 worked in hospitals equipped with the prevention process of perioperative hypothermia. Electronic (placed in the nasopharynx probe) (73.24%) and mercury thermometers (66.20%) were the commonly used temperature monitoring devices in most participants’ hospitals (Table 1and Fig. 1).

Knowledge, attitude and practice dimensions

The knowledge, attitude and practice scores were 5.36 ± 2.06 (total score of 12), 47.54 ± 5.44 (total score of 55) and 31.57 ± 4.37 (total score of 40), respectively. Additionally, the knowledge scores of the surgeon (5.86 ± 2.48), anesthesiologists (4.52 ± 1.66), and nurses (5.46 ± 2.06) were significantly different (P = 0.046). Participants with different demographic characteristics had no significant difference in attitude scores. The practice score significantly differed between participants with different education (P = 0.025) and occupations (P = 0.023). The practice scores were higher in participants with perioperative hypothermia processes in their work units (Table 1). For the knowledge items, the correct responses ranged from 13.62 to 89.67%. The item with the highest correct response rate was that “patients aged > 60 had a higher incidence of hypothermia and a longer recovery time”. There were two items with a correct rate of less than 20%. Only 29 (13.62%) participants correctly responded to the ambient temperature requirements during surgery, and 35 (16.43%) participants correctly answered that “for patients with operation time greater than 30 minutes, it is recommended to use a warming device before anesthesia induction”. For the attitude items, most participants agreed that active use of insulation measures during surgery effectively prevents perioperative hypothermia (69.95% strongly agreed and 26.29% relatively agreed). Participants overwhelmingly agreed that surgeons (82.16%), anesthesiologists (96.24%), and nurses (95.31%) all play a critical role in the prevention and treatment of perioperative hypothermia. The majority of them believed that it is necessary to train surgeons (94.37%), anesthesiologists (64.79%), and nurses (96.72%) in the knowledge of prevention and treatment of perioperative hypothermia. For the practice items, over 90% of respondents reported that they would check and warm the exposed limb and avoid disinfectant wetting the surgical blankets before surgery. Perioperative temperature records were almost kept electronically (76.1%). About half of the participants monitored the patient’s temperature at the nasal pharynx during the perioperative period (60.6%). In addition, 36.6% of physicians and nurses would consider charging when choosing or using perioperative heating equipment (Table 2).

Pearson correlation analysis

The knowledge scores had a weak positive but significant correlation with attitude scores (r = 0.21, P = 0.002) and practice scores (r = 0.23, P = 0.001). Moreover, attitude score was positively correlated with practice score (r = 0.57, P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Multivariate regression analysis

Multivariate logistic regression for nurses showed that female (OR = 0.286, 95%CI: 0.09–0.902) and 11–15 years of working experience (OR = 0.298, 95%CI: 0.094–0.95) were independently associated with knowledge. Attitude (OR = 1.275, 95%CI: 1.169–1.392) and female (OR = 0.325, 95%CI: 0.12–0.883) were independently associated with practice (Table 4).

SEM

The SEM model fit results showed an RMSEA of < 0.001, indicating good fit; CFI of 1.000, indicating good fit; TLI of 1.000, indicating good fit; and SRMR of < 0.001, also indicating good fit, and found that knowledge had a direct effect on attitude (β = 0.56, P = 0.002), and an indirect effect on practice (β = 0.25, P = 0.003). Attitude had a direct effect on practice (β = 0.45, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2; Table 5).

Subgroup analysis

The subgroup analysis conducted on nurse showed that the knowledge, attitude and practice score of nurses was 5.46 ± 2.06 (total score of 12, 45.5%), 47.54 ± 5.44 (total score of 55, 86.4%), and 31.57 ± 4.37 (total score of 40, 78.9%). Nurses employing warm blankets for heat preservation in the operating room were more likely to hold a positive attitude compared to those who did not use this equipment (P = 0.038). Similarly, the application of warm air blowers (P = 0.045) and liquid incubators (P = 0.042) was associated with a more favorable attitude. Furthermore, nurses who utilized infusion warmers for heat preservation were more likely to have a positive attitude towards practice (P = 0.020). Notably, a statistically significant association was identified between adherence to perioperative heat preservation procedures and higher practice scores among nurses (P = 0.005) (Table 6).

Discussion

This study assessed the KAP of perioperative hypothermia among nurses, surgeons and anesthesiologists. The results showed that physicians and nurses had a positive attitude, but they had a lack of adequate knowledge in some aspects. High knowledge and attitude scores were independent protective factors for proactive practice.

Inadvertent hypothermia during the perioperative period can have serious adverse consequences18,19,20. Previous studies in Gambia, the United States of America, and Australia indicated that healthcare providers possessed a good understanding and awareness in some domains of perioperative hypothermia prevention, but their practice levels were unsatisfactory20,21,22. Thus, identifying and managing inadvertent hypothermia is an important aspect of perioperative management23. Concordant with the previous studies, most of nurses, surgeons and anesthesiologists in this study were familiar with the perioperative hypothermia criteria, and had a good understanding of the risk factors and hazards of hypothermia during the perioperative period. However, many of them were unfamiliar with the related preventive measures, especially on applying heating equipment and maintaining ambient temperature before anesthesia induction, which was in line with previous studies22,24. Koh et al.11 reported that some healthcare providers did not understand perioperative temperature management practice guidelines, with poor compliance. Therefore, it is necessary to carry out targeted education measures for physicians and nurses. The training should focus on the specific knowledge of clinical preventive measures for hypothermia.

The successful practice of preventing perioperative hypothermia requires an understanding hypothermia knowledge and positive, cautious attitude. In the traditional concept, hypothermia would effectively reduce the basal metabolic rate of the human body and protect important organs25. Some healthcare providers believed that perioperative hypothermia protection was redundant, and senior nurses were more likely to downplay the need for hypothermia protection during the perioperative period. In the present study, a few nurses, surgeons and anesthesiologists believed that intraoperative hypothermia was a common phenomenon and that it did not matter if it occurred as long as the surgery was successful. On the whole, the attitude of the participants toward the prevention of perioperative hypothermia was positive. Almost all participants in this study believed they played an essential role in preventing and treating perioperative hypothermia. Most physicians and nurses agreed they would feel guilty if the patients suffered from inadvertent hypothermia because heat preservation measures were not actively applied. Previous studies focused more on healthcare providers’ knowledge and practice11,26, while this study provided more information about the attitude toward unintentional perioperative hypothermia prevention.

In this study, most nurses, surgeons and anesthesiologists had received at least one training on perioperative hypothermia, and a few had not received any training. Given the key role of medical staffs in preventing perioperative hypothermia, relevant training should be carried out. Physicians and nurses using perioperative heat preservation techniques at their working hospitals had higher practice scores than those without. However, several barriers to guideline adherence were identified, which varied among different professional roles. For surgeons, the main challenges included high workload demands that sometimes led to prioritizing surgical efficiency over temperature management, and concerns about heating equipment interfering with the sterile field. Anesthesiologists faced difficulties in balancing multiple monitoring parameters simultaneously, particularly during complex cases with hemodynamic instability. Operating room nurses encountered challenges related to limited availability of warming devices and the need to coordinate temperature management with other urgent care requirements. Additional barriers included resource constraints in smaller hospitals, variations in infrastructure among different facilities, and the absence of standardized protocols that account for different surgical specialties. Addressing these profession-specific and systemic challenges requires targeted interventions. For surgeons, this might include integrating warming protocols into surgical timeout procedures and providing evidence on how proper temperature management can reduce surgical complications. Anesthesiologists could benefit from automated temperature monitoring systems that integrate with existing vital sign displays, while nurses may need additional support staff and clear allocation of responsibilities for temperature management. The development of standardized heat preservation protocols should be tailored to both specific hospital settings and different surgical specialties. Moreover, hospital infrastructure and resource allocation need to be considered when implementing these protocols, particularly in facilities with limited resources. Multidisciplinary collaboration and leadership support are critical for enhancing compliance with perioperative temperature management guidelines, especially in addressing workload constraints and resource limitations. Therefore, it would be beneficial for hospitals to formulate a perioperative heat preservation process to standardize the clinical practice of physicians and nurses. Previous studies also reported similar results. Indeed, respondents who actively stayed warm while operating in hospitals with standardized operating procedures (SOP) had improved behavioral patterns11. Systematic changes in hospital SOP have been proven to improve compliance with the guidelines and clinical outcomes27. In addition, there was a positive correlation between attitude and practice score. The multiple regression analysis showed that only knowledge and attitude scores were the protective factors of good practice, while the demographic information, such as professional title, showed no statistical significance. Based on these results, physicians and nurses showed a positive attitude toward preventing perioperative hypothermia, but they had insufficient knowledge. Therefore, it might improve the compliance rate of physicians and nurses with the guidelines by growing their knowledge of treatment and prevention of perioperative hypothermia.

Nurses utilizing specialized equipment like warm blankets, warm air blowers, liquid incubators, and infusion warmers exhibited more positive attitude toward these practice. This correlation suggests a potential link between advanced tools and an enhanced recognition of temperature regulation’s importance. Furthermore, the study establishes a significant correlation between adherence to heat preservation protocols and higher practice scores among nurses. This underscores a direct connection between protocol compliance and overall nursing quality, emphasizing the significance of maintaining patient temperatures during surgical procedures2,28.

The multivariate logistic regression analysis adds depth by identifying key factors influencing nurses’ knowledge and practice of heat preservation. The observation that nurses with 11–15 years of experience demonstrated lower knowledge levels and less favorable attitude. This highlights a need for continuous education, particularly for experienced nurses unfamiliar with evolving techniques24,29.

This study offers valuable insights into the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of medical staff regarding perioperative hypothermia prevention; however, some limitations should be noted. As a questionnaire-based study, it may not capture nuanced perspectives, and self-reported data could introduce reporting or recall bias. Although the sample size met the minimum requirement, the relatively small number of valid questionnaires (n = 213) from eight hospitals may limit the generalizability of the findings. The use of convenience sampling, while practical, may have led to selection bias, potentially overrepresenting participants more interested in or knowledgeable about the topic. Moreover, the predominance of tertiary hospitals in urban areas, with limited representation from secondary hospitals or rural and community centers, may restrict the applicability of the results to smaller or less-resourced institutions. This is particularly relevant in China, where significant disparities exist between urban and rural healthcare systems; however, our study did not directly compare these settings due to the limited representation of rural and community centers. These limitations highlight the need for future studies to include a broader range of healthcare settings to better reflect the diversity of China’s healthcare landscape. Additionally, the study did not perform cross-validation or expert content validation, which may limit the robustness of the questionnaire’s psychometric properties. Future studies should consider incorporating these methods to further validate the questionnaire.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this exploratory study from northern China indicates that while most physicians and nurses had positive attitudes and acceptable practice levels, their knowledge of unintentional perioperative hypothermia prevention was generally inadequate. Knowledge and attitude were identified as factors potentially influencing practice. Although the small regional sample limits generalizability, these findings highlight the need for targeted training programs and standardized protocols to improve adherence to perioperative hypothermia prevention guidelines in similar healthcare settings.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Bräuer, A., Müller, M. M., Wetz, A. J., Quintel, M. & Brandes, I. F. Influence of oral premedication and prewarming on core temperature of cardiac surgical patients: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 19, 55 (2019).

Liu, M. & Qi, L. The related factors and countermeasures of hypothermia in patients during the anesthesia recovery period. Am. J. Transl Res. 13, 3459–3465 (2021).

Madrid, E. et al. Active body surface warming systems for preventing complications caused by inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4, Cd009016 (2016).

Dagli, R., Bağbancı, M., Dadalı, M. & Erşekerci, E. Are operating rooms with laminar airflow a risk for inadvertent perioperative hypothermia during ureterorenoscopic lithotripsy under spinal anesthesia?? A prospective randomized clinical trial. J. Patient Saf. 18, e1027–e1033 (2022).

Sabbag, I. P. et al. Postoperative hypothermia following non-cardiac high-risk surgery: A prospective study of Temporal patterns and risk factors. PLoS One. 16, e0259789 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Intraoperative interventions for preventing surgical site infection: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2, Cd012653 (2018).

Kang, S. & Park, S. Effect of the ASPAN guideline on perioperative hypothermia among patients with upper extremity surgery under general anesthesia: A randomized controlled trial. J. Perianesth Nurs. 35, 298–306 (2020).

Simegn, G. D., Bayable, S. D. & Fetene, M. B. Prevention and management of perioperative hypothermia in adult elective surgical patients: A systematic review. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond). 72, 103059 (2021).

Alderson, P. et al. Thermal insulation for preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. Cd009908 (2014).

Li, L., Zhang, J., Qiao, Q., Wu, L. & Chen, L. Development, Reliability, and Validity of theKnowledge-Attitude-Practice Questionnaire of Foreigners on Traditional Chinese Medicine Treatment. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 8527320 (2020) (2020).

Koh, W. et al. Perioperative temperature management: a survey of 6 Asia-Pacific countries. BMC Anesthesiol. 21, 205 (2021).

Forbes, S. S. et al. Evidence-based guidelines for prevention of perioperative hypothermia. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 209, 492–503e (2009). 1.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guidelines. Hypothermia: prevention and management in adults having surgery. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Copyright © NICE 2019.; (2016).

Jia, W., Liu, W. & Qiao, X. Chinese expert consensus on enhanced recovery after hepatectomy (Version 2017). Asian J. Surg. 42, 11–18 (2019).

Yi, B. An overview of the Chinese healthcare system. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 10, 93–95 (2021).

Calvo Vecino, J. M. et al. Clinical practice guideline. Unintentional perioperative hypothermia. Rev. Esp. Anestesiol Reanim (Engl Ed). 65, 564–588 (2018).

Wilson, R. D. et al. Guidelines for Antenatal and Preoperative care in Cesarean Delivery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society Recommendations (Part 1). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 219. 523.e1-523.e15 (2018).

Forstot, R. M. The etiology and management of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. J. Clin. Anesth. 7, 657–674 (1995).

Shaw, C. A., Steelman, V. M., DeBerg, J. & Schweizer, M. L. Effectiveness of active and passive warming for the prevention of inadvertent hypothermia in patients receiving neuraxial anesthesia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Anesth. 38, 93–104 (2017).

Cho, S. A. et al. Clinical efficacy of short-term prewarming in elderly and adult patients: A prospective observational study. Int. J. Med. Sci. 19, 1548–1556 (2022).

Jallow, O. & Bayraktar, N. Nurses’ Awareness and Practices of Unintentional Perioperative Hypothermia Prevention: A Cross-Sectional Study. Ther. Hypothermia Temp. Manag (2022).

Giuliano, K. K. & Hendricks, J. Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia: current nursing knowledge. Aorn J. 105, 453–463 (2017).

Rasmussen, J. M. et al. Epidemiology, management, and outcomes of accidental hypothermia: A multicenter study of regional care. Am. Surg. 88, 1062–1070 (2022).

Hegarty, J. et al. Nurses’ knowledge of inadvertent hypothermia. Aorn J. 89, 701–704 (2009).

Urits, I. et al. A comprehensive update of current anesthesia perspectives on therapeutic hypothermia. Adv. Ther. 36, 2223–2232 (2019).

İnal, M. A., Ural, S. G., Çakmak, H., Arslan, M. & Polat, R. Approach to perioperative hypothermia by anaesthesiology and reanimation specialist in Turkey: A survey investigation. Turk. J. Anaesthesiol. Reanim. 45, 139–145 (2017).

Scott, A. V. et al. Compliance with surgical care improvement project for body temperature management (SCIP Inf-10) is associated with improved clinical outcomes. Anesthesiology 123, 116–125 (2015).

Doyle, G. A., O’Donnell, S., Cullen, K., Quigley, E. & Gibney, S. Understanding the cost of care of type 2 diabetes mellitus - a value measurement perspective. BMJ Open. 12, e053001 (2022).

Mitoma, R. & Yamauchi, T. Effectiveness of a learning support program for respiratory physical assessment: A quasi-experimental study. PLoS One. 13, e0202998 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wei Guo and Weixuan Sheng carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript. Yang Han and Ying Zhang, Xun Zhao performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and informed consent

This work has been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Association. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Shijitan Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University [Sjtky11-1x-2023(004)]. Informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, W., Sheng, W., Han, Y. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of medical staffs in the operating room towards unintentional perioperative hypothermia prevention: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 15178 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00202-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00202-3