Abstract

Climate change negatively affects mountainous plants and leads to their range contraction or extinction. Cushion plants are the essential components of mountainous ecosystems. Although cushions represent the dominant vegetation form of the mountains of the Irano-Anatolian Biodiversity Hotspot, the impacts of climate change on these plants have been merely studied. The present study investigates the effects of climate change on the distribution of endemic cushion species in the Khorassan-Kopet Dagh (KK) floristic province, the eastern-most part of the Irano-Anatolian Biodiversity Hotspot. We predicted the current and future range of 19 cushions in 2040 and 2100, using 19 bioclimatic layers along with two different SSPs and an ensemble of 12 modeling algorithms. These species belong to Acantholimon, Acanthophyllum, Astragalus, Jurinea, and Thymus genera. Our findings revealed that approximately all studied species will face range contraction. On the other hand, Jurinea antunowi, Acantholimon restiaceum, and Acanthophyllum speciosum will show negligible responses to climate change effects. Moreover, all analyzed species would shift upward in their altitudinal distribution range. The predicted range size contraction of the surveyed genera will vary between 36 to 91 percent, where Acanthophyllum and Thymus will show the least and the most contraction, respectively. Based on our findings, we have provided recommendations for conservation of vulnerable species and sustainable mountainous habitats restorations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cushions (pulvinate plant forms) with "tightly packed foliage held close to the soil surface, and a relatively even and rounded canopy form"1 are significant ecosystem engineers that can alter the local soil temperature and moisture2,3. These nurse plants are facilitators for the other species4,5,6,7. Cushions increase and maintain local species diversity, especially in the stressful conditions of mountainous habitats6,8. Furthermore, by reducing environmental fluctuations, these plants positively affect the reproduction and establishment of herbaceous plants and the formation of the soil seed bank9.

Cushion plants are a critical part of mountainous vegetation, and their distribution or abundance changes can significantly affect plant communities10. Climate change can alter temperature regimes, precipitation and water availability, snow cover, and biotic interactions11. These factors have a negative impact on cushion plant distribution and abundance12,13. Thus, examining cushion plants’ response to climate change is a crucial step towards sustainable management of mountainous habitats to maintain their services for the future.

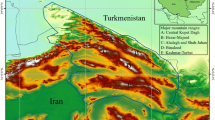

The Khorassan-Kopet Dagh (KK) floristic province is in the eastern part of the Irano-Anatolian Biodiversity hotspot14,15. It is a mountainous region that acts as a transitional zone between the different phytogeographical units of the Middle East15. The KK has large mountain ranges, namely the Kopet Dagh, Hezar Masjed, Binalood, and Aladagh Mountains (Fig. 1)15,16,17. Cushion plants, especially thorn-cushion species, constitute the dominant mountainous vegetation form of the KK15,18. The cushion species of the KK belong to different genera, i.e., Acantholimon, Acanthophyllum, Anabasis, Astragalus, Dionysia, Jurinea, Onobrychis, and Thymus15,18,19. These plants occur in various communities in the region (Fig. 1)16,19,20,21. These species have different ecological roles that lead to the preservation of the biodiversity of KK’s mountains8,22,23.

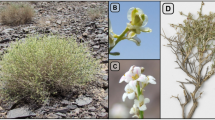

a: Study area, the Khorassan-Kopet Dagh floristic province (KK). The original figure was adopted from Erfanian et al. (17). b-d: cushion vegetation type on elevations of the main ranges of KK (by Zohreh Atashgahi), (b) Onobrychis, Acanthophyllum, and Acantholimon in Binalood, (c) Acanthophyllum and Acantholimon in Aladagh, (d) and Onobrychis cornuta and Acantholimon spp. in Hezar Masjed.

Habitat suitability modeling (HSM) is used to predict species’ climate niches and project potential future range shifts to evaluate the vulnerability of plant species to changing climate conditions24,25,26. The results of HSM can inform the development of adaptive management strategies, such as assisted migration, to mitigate the effects of climate change24,27. Although KK hosts a considerable number of 356 endemic plant species, the response of these endemic species to climate change has remained understudied. Two previous studies have evaluated the impacts of climate change on endemic (non-cushion forming) plants in KK (i.e., Behroozian et al.28 and Erfanian et al.17). However, the impacts of climate change on KK’s endemic cushion species have not been investigated. Few studies assessed the impacts of climate change on cushion plants of the Irano-Anatolian Biodiversity hotspot (e.g., Karimian et al.29, Mahmoudi Shamsabad et al.30, and Sheikhzadeh Ghahnaviyeh et al.31). However, they have focused on non-endemic taxa.

Mountainous habitats of KK are generally subjected to different disturbances, such as grazing16,23,32 and land use changes8,33. Predicting the response of cushion plants to climate change will enable managers to preserve endangered species and plan appropriate restoration practices based on cushion species whose distribution range remains unaffected by climate change. The present study aimed to assess the impact of climate change on the distribution range of endemic cushions in the KK. This is the first study investigating the response of KK’s endemic cushions to climate change. We hypothesize that (a) climate change, particularly in a pessimistic scenario, can significantly reduce the distribution of these plants; (b) the species within the same genus have similar responses to climate change due to their shared evolutionary histories. We also test whether species within a similar elevation range respond similarly to climate change. Our findings will enable us to identify the most-vulnerable and indifferent species to climate change. Management strategies for vulnerable species will be presented. The indifferent species can be used in long-term restoration practices in the region.

Materials and methods

Study area

The KK floristic province is a transitional zone that connects different phytogeographical units of the Irano-Turanian region15. The KK, with an area of 165,000 km2, encompasses a complex topography ranging from approximately 250 to elevations higher than 3000 m a.s.l.15 (Fig. 1). The dominant climatic condition of the region is the continental climate. Mountain ranges in the KK have a Mediterranean or Irano-Turanian xeric-continental bioclimate with an average annual precipitation of 300–380 mm. The mean annual temperature ranges between 12–19 °C34. The KK is home to diverse vegetation types, among which the montane steppes and grasslands are the most abundant15 (Fig. 1). The region hosts 2576 vascular plants, of which 356 (13.8 percent of the total species pool) are endemic35. Most of the KK’s endemic species are range-restricted and rare17,36. Various disturbances, such as overgrazing, land use change, and recreation activities, threaten the mountainous habitats in the KK14,16,32,33,37,38. Approximately eight percent of the KK habitats are protected and managed under different protection guidelines18.

Species data

The definition of cushion plants in Pérez-Harguindeguy et al. (1) was followed to determine the cushion species of the study region. The list of the endemic plants of the KK35, as well as the updated literature on the region’s flora, was reviewed to list the cushion species of the region. Then, we collected the occurrence points through (a) the field surveys conducted in KK during the past ten years (2013–2023) (for all of the field surveys permissions for plant collection have been obtained); (b) specimens evaluation, mainly those that were deposited at Herbarium of Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, FUMH (mainly focused on the collection of plant species of the KK); (c) review of literature including Atashgahi et al.19, Atashgahi et al.39, Arjmandi et al.37, Assadi et al. (Flora of Iran40), Maleki Sadabadi et al.41, Parishani et al.42, Pirani et al.43, and Rechinger (Flora Iranica44). We tried to collect occurrence records from all climatic conditions where species were present. Three sets of pseudoabsence points were generated for each species using the biomod2 package45 for the modeling. The number of random pseudoabsence points was set to 3 × number of occurrence records.

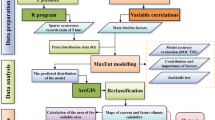

Environmental data

We used 19 bioclimatic layers (Supplementary 1), with a 1 km2 resolution, that are reliable in defining the physio-ecological tolerances of species46. These layers were downloaded from Worldclim47. To download future layers, we selected the Hadley Centre Global Environmental Model version 2‐Earth System (HadGEM2-ES), general circulation model (GCM), and two Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) scenarios, including SSP126 (most optimistic) and SSP585 (most pessimistic). We chose the HadGEM2-ES model because it showed appropriate temperature forecasting compared to the data from different synoptic stations in Iran17. We chose the years to use the HSM in the near future (2021–2040, which is called 2040 hereafter) and the far future (2080–2100, which is called 2100 hereafter).

We performed a pre-run to select the most suitable layers. The pre-run had a set of pseudoabsence data and a Maxent algorithm with ten replications. We used the Maxent algorithm because it showed good performance when there was a lack of resources to use multiple algorithms48 to make our results reproducible even using low-resource computations. Then, the first layers that account for 80 percent of variable importance were selected. We calculated the variance inflation factor (VIF) for the selected layers to remove collinear layers. VIFs were calculated by performing a step-by-step process using the usdm package (Naimi et al. 2014). We selected variables with a VIF below five. The selected variables for each species are presented in Table 1.

Modeling settings

Twelve modeling algorithms, including the Generalized Linear Model (GLM), Generalized Additive Model (GAM), Generalized Boosting Model (GBM), Classification Tree Analysis (CTA), Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Surface Range Envelop (SRE), Multiple Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS), Random Forest (RF), Maximum Entropy (MAXENT), Maximum Entropy (MAXNET), Flexible Discriminant Analysis (FDA) and eXtreme Gradient Boosting Training (XGBOOST) were used to construct the models in the current study.

The occurrence data were randomly split into two subsets, with 70 percent of the data used for model calibration and the remaining 30 percent used for model evaluation. The data was split because we had no independent data for model evaluation. The number of replications was set to 2. Therefore, we constructed 72 models for each species. We employed the True Skill Statistic (TSS) along with the Area Under Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operation Curves to measure HSM performance. To project the final maps, we used binary transformation. For binary transformation, we employed the threshold that maximizes TSS to convert occurrence probability values into presence/absence predictions. These calculations were performed using the biomod2 package.

Ensemble forecasting

To obtain the final models, we employed the ensemble forecasting procedure. We selected those with a TSS and AUC above 0.6 to combine models. Ensemble models were projected for current and future conditions at a 1 km2 resolution. The ensemble models were transformed into binary presence-absence predictions using the threshold that maximizes TSS46. The ensemble forecasting was performed using the biomod2 package.

Range and elevation shifts

To assess the effects of climate change on the range size of the studied species, we compared each species’ future distribution to its current distribution. For each species, four distinct habitat types were categorized: (a) stable habitats – habitats that are suitable in current and future climatic conditions; (b) lost habitats – currently suitable habitats that will not remain suitable in the future; (c) gained habitats – currently unsuitable habitats that will become suitable in the future; and (d) unsuitable habitats – habitats that are unsuitable for species both in current and future climatic conditions. We predicted range size changes using the biomod2 package.

The current elevation and future elevation range of each species was determined using the terra package49. The reported elevation range includes the midspread (quartile 1 and 3 values) of extracted elevation using the ensemble binary maps. For future elevation ranges, we concentrate on SSP 585 of 2100. For those species that would become completely extinct in this scenario, we used the value of SSP 585 of 2040.

Results

We identified 34 endemic cushion species for KK, of which only 19 had an adequate number of occurrence records suitable for the HSM (SM 2–7). The modeled species are the members of the genera Acantholimon, Acanthophyllum, Astragalus, Jurinea, and Thymus. The information regarding the number of occurrence records, variable contributions, and the performance metrics AUC and TSS for the ensemble model are detailed in Table 1.

The results of HSM for the five modeled genera are summarized below. The current range size and future range size changes and the current and future distribution of the modeled species are presented in Tale 3 and Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, respectively. The details of range size changes under SSP126 and SSP585 scenarios for each species are presented in Table 1. Current and future elevational range of the modeled species are presented in Fig. 6.

Acantholimon

The future range size changes for eight Acantholimon species were modeled. The average range size change for endemic species of Acantholimon is -64 percent (Table 1).

Acantholimon alavae

The ensemble habitat suitability map indicates that the area of currently suitable habitats for A. alavae is 5704 km2, delimited within 818–1235 m above sea level (m a.s.l.) (Fig. 2; Table 1; Fig. 6). This plant’s limited potential suitable habitat is restricted to the mountains located east of the KK. The range size analysis shows that this species will be lost in future (Table 1).

Acantholimon avenaceum

The ensemble habitat suitability map indicated that the current range size for A. avenaceum is 51,296 km2, within the elevation range of 1628–2066 m a.s.l. (Fig. 2; Table 1; Fig. 6). The distribution range of this species encompasses the Kopet Dagh mountains of Turkmenistan and extends to the Kopet Dagh-Hezar Masjed mountains in Iran, as well as the Aladagh-Binalood range, and ends in Kashmar-Torbat ranges. The potential distribution range of A. avenaceum is predicted to shift upward (2082–2409 m a.s.l.) in the elevations under climate change. The average range size changes for this species will be -80.7 percent.

Acantholimon blandum

The habitat suitability map demonstrated that the current range size of A. blandum is 26,600 km2, within the elevation range of 1144–1996 m a.s.l. (Fig. 2; Table 1; Fig. 6). The distribution range of this species is mainly restricted to the high mountains of Turkmenistan and Iran on the Kopet Dagh-Hezar Masjed, Aladagh-Binalood, and Kashmar-Torbat ranges. It is predicted that A. blandum will face elevation range contraction (930–1485 m a.s.l.) and remain in its current eastern habitats. The average range size changes for this species will be -89.0 percent.

Acantholimon gorganense

The current range size of A. gorganense is 12,575 km2, within the elevation range of 1762–2216 m a.s.l. (Fig. 2; Table 1; Fig. 6). Currently, suitable habitats for this plant are restricted to the high elevations of the Kopet Dagh-Hezar Masjed, Ghorkhod, Salook, and Aladagh ranges to the eastern extension of the Alborz mountain range in Almeh. It is predicted that A. gorganense will experience an eastward shift, as well as an upward migration in the elevations (2259–2522 m a.s.l.) under the climate change. The average range size changes for this species will be -72.0 percent.

Acantholimon pterostegium

The ensemble habitat suitability map demonstrated that the current range size of A. pterostegium is 61,183 km2, within the elevation range of 1303–1704 m a.s.l. (Fig. 2; Table 1; Fig. 6). The current suitable habitats of this species are limited to the low and mid-range elevations of central KK. It is expected that A. pterostegium will migrate eastward and shift upward to higher elevations (1495–1904 m a.s.l.) under climate change. The average range size changes for this species will be -54.6 percent.

Acantholimon raddeanum

The ensemble habitat suitability map demonstrated that the current range size of A. raddeanum is 22,459 km2, within the elevation range of 1757–2179 m a.s.l. (Fig. 2; Table 1; Fig. 6). The currently suitable habitats of this species are delimited to mid and high-elevation ranges of the Hezar Masjed and Binalood Mountains. It is predicted that A. raddeanum will shift upward in the elevations (2619–2846 m a.s.l.) under climate change. The average range size changes for this species will be -68.9 percent.

Acantholimon restiaceum

The ensemble habitat suitability map indicated that the current range size for A. restiaceum is 21,361 km2, within the elevation range of 994–1582 m a.s.l. (Fig. 2; Table 1). The distribution range of this species is mainly limited to the southeastern parts of KK, on the Torbat-e-Jam and Sarakhs mountains. It is expected that A. restiaceum will experience both eastward and upward (1155–1457 m a.s.l.) shifts under climate change. The average range size changes for this species will be + 2.0 percent.

Acantholimon spinicalyx

The ensemble habitat suitability map demonstrated that the current range size of A. spinicalyx is 19,677 km2, within the elevation range of 1244–1698 m a.s.l. (Fig. 2; Table 1; Fig. 6). The current suitable habitats of this species are limited to the south of KK and the south-facing slopes of the Kashmar-Torbat range. The potential distribution range of A. spinicalyx is expected to shift upward in the elevations (2458–2526 m a.s.l.) under climate change. The average range size changes for this species will be -52.0 percent.

Acanthophyllum

The future range size changes for two Acanthophyllum species were modeled. The average range size change for Acanthophyllum is -36 percent (Table 1).

Acanthophyllum adenophorum

The habitat suitability map indicated that the current range size for Ac. adenophorum, is 65,173 km2, within the elevation range of 1242–1762 m a.s.l. (Fig. 3; Table 1; Fig. 6). This species has a wide distribution in the lowlands of central KK, especially within the Kopet Dagh-Hezar Masjed and Aladagh-Binalood Mountains. Based on our results, Ac. adenophorum will shift upward under the climate change (2297–2678 m a.s.l.). The average range size changes for this species will be -67.8 percent.

Acanthophyllum speciosum

The ensemble habitat suitability map indicated that the current range size for Ac. speciosum is 22,076 km2, within the elevation range of 1366–1892 m a.s.l. (Fig. 3; Table 1; Fig. 6). The suitable habitat is limited to the lowland ranges between the Binalood and Hezar Masjed Mountains. It is predicted that Ac. speciosum will experience an eastward shift as well as an upward migration (1743–2186 m a.s.l.) under climate change. The average range size changes for this species will be -4.0 percent.

Astragalus

The future range size changes for four Astragalus species was modeled. The average range size change for endemic cushion species of the genus Astragalus in the KK is -69.2 percent.

Astragalus cystosus

The ensemble habitat suitability map demonstrated that the current range size of As. cystosus is 2486 km2, within the elevation range of 1656–1958 m a.s.l. (Fig. 4; Table 1; Fig. 6). The current suitable habitats of this narrowly distributed species are limited to the mid-range elevations of the Kashmar-Torbat Mountains. It is predicted that all of the current habitats of As. cystosus will be lost. The survival of this species would potentially rely only on the new habitats that would be gained upward (1842–2140 m a.s.l.) and westward. The average range size changes for this species will be -75.1 percent.

Astragalus hypsogeton

The ensemble habitat suitability map indicates that the area of currently suitable habitats for As. hypsogeton is 7509 km2, within the elevation range of 1877–2204 m a.s.l. (Fig. 4; Table 1; Fig. 6). Although the existing documentation of this species is from the Aladagh and Binalood mountain ranges, this species has potential suitable habitats in Hezar Masjed, too. It is expected that As. hypsogeton will migrate eastward and shift upward (1989–2374 m a.s.l.) under climate change. The average range size changes for this species would be -89.9 percent.

Astragalus raddei

The ensemble habitat suitability map indicates that the area of currently suitable habitats for As. raddei is 28,383 km2, within the elevation range of 1586–2082 m a.s.l. (Fig. 4; Table 1; Fig. 6). The species has a wide distribution and is found in most of the mountains and foothills of the KK, including the Kopet Dagh in Turkmenistan and Iran, Hezar Masjed, Aladagh, and Binalood mountain ranges. It is expected that As. raddei will shift eastward and experience an upward migration (1989–2374 m a.s.l.) under climate change. The average range size changes for this species will be -70.9 percent.

Astragalus turkmenorum

The ensemble habitat suitability map demonstrated that the current range size of As. turkmenorum is 15,380 km2, within the elevation range of 970–1544 m a.s.l. (Fig. 4; Table 1; Fig. 6). The currently suitable habitats of this species are limited to the northern parts of the KK within the Kopet Dagh elevations. It is expected that As. raddei will shift westward and undergo an upward migration (1390–1694 m a.s.l.) along the altitudinal range under climate change. The average range size changes for this species will be -40.9 percent.

Jurinea

The future range size changes for four Jurinea species was modeled. The average range size change for endemic species of Jurinea is -42 percent (Table 1).

Jurinea antunowi

The ensemble habitat suitability map demonstrated that the current range size of J. antunowi is 38,317 km2, within the elevation range of 444–1404 m a.s.l. (Fig. 5; Table 1; Fig. 6). The currently suitable habitats of this species are the Kopet Dagh in Turkmenistan and Iran, Hezar Masjed, Aladagh, and parts of the Binalood Mountains. It is predicted that J. antunowi will have no elevational responses to climate change (437–1389 m a.s.l.) and gain new habitats under climate change. The average range size changes for this species will be + 6.2 percent.

Jurinea catharinae

The ensemble habitat suitability map demonstrated that the current range size of J. catharinae is 59,744 km2, within the elevation range of 897–1531 m a.s.l. (Fig. 5; Table 1; Fig. 6). The currently suitable habitats for this species are the eastern parts of the KK in the Hezar Masjed and Kopet Dagh, Binalood and kashmar-Torbat Mountains. It is expected that J. catharinae will experience an eastward shift as well as elevational range contraction (876–1352 m a.s.l.) under climate change. The average range size changes for this species will be -35.3 percent.

Jurinea kopetensis

The ensemble habitat suitability map demonstrated that the current range size of J. kopetensis is 10,574 km2, within the elevation range of 1064–1811 m a.s.l. (Fig. 5; Table 1; Fig. 6). The currently suitable habitats of this species are limited to a low elevation of the western slopes of Hezar Masjed and the eastern slopes of Binalood Mountains. It is predicted that all of the current habitats of J. kopetensis will be lost. The survival of this species would potentially rely only on the new habitats that would be gained with an elevational range contraction (914–1478 m a.s.l.). The average range size changes for this species will be -95 percent.

Jurinea sintenisii

The ensemble habitat suitability map demonstrated that the current range size of J. sintenisii is 37,607 km2, within the elevation range of 1167–1760 m a.s.l. (Fig. 5; Table 1; Fig. 6). This species has a relatively wide distribution range and has a suitable habitat in most of the KK’s mountains in Turkmenistan and Iran. It is predicted that J. sintenisii will face elevational range contraction (921–1595 m a.s.l.) under climate change. The average range size changes for this species will be -42.7 percent.

Thymus

The single investigated species of Thymus will face a range size reduction (Fig. 3; Table 1).

Thymus transcaspicus

The ensemble habitat suitability map demonstrated that the current range size of T. transcaspicus is 30,274 km2, within the elevation range of 1323–1957 m a.s.l. (Fig. 3; Table 1; Fig. 6). The currently suitable habitats of this species are delimited to the northern mountains of KK, including Aladagh, Kopet Dagh, and Hezar Masjed. It is expected that T. transcaspicus will move upward (2142–2524 m a.s.l.) under climate change. The average range size changes for this species will be -90.9 percent.

Discussion

Cushion plants are key species of the mountainous habitats9,50. The Irano-Anatolian biodiversity hotspot has vast mountain ranges36. However, there is no comprehensive study on the effects of climate change on cushion species of the region. We examined the impact of climate change on endemic cushions of KK, the eastern part of the Irano-Anatolian Biodiversity Hotspot.

How climate change affects the distribution of cushions in KK

Here, we observed that many cushions would experience range contraction due to climate change, with A. alavae, J. kopetensis, and T. transcaspicus facing more than 90 percent average range loss (most-vulnerable). On the other hand, A. restiaceum, Ac. speciosum, and J. antunowi are species with negligible (-10 to + 10 percent average range size change) responses to climate change.

Change in habitats due to climate change is reported for all endemic species of the Irano-Anatolian Biodiversity Hotspot51. The majority of the species studied by the present study will shift upward along their elevational range, considering their spatial movement. The upward shift includes gaining new habitats for only six species (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5); the remaining will lose their lower-elevation habitats and retain in their higher-elevation habitats. It should be noted that none of the modeled species can migrate to elevations above 3000 m a.s.l., revealing the upward boundary for these taxa and suggesting an increased competition in elevations below this limit. The upward migration is consistent with the results of several previous studies in different regions, e.g., Australia and Switzerland52, China53, the Zagros Mountains in Iran54, and Iraq55. There are species that face elevational range contraction (i.e., those of Jurinea along with Acantholimon restiaceum), an extreme response was that of the Acantholimon blandum that will lose more than half of its current elevational range going downward. Species lose their upper elevation suitable habitats primarily because warming temperatures reduce the cool, stable environments they need, and other climate-related changes (e.g., reduced snow cover and altered precipitation) along with genetic erosion exacerbate this loss56,57. As well as experiencing the upward shift, seven species will move eastward, and two will move westward.

Comparing range shifts of the surveyed genera

Here, we modeled the response of 19 cushion species, arranged in five genera, to climate change. Although these plants share similar life forms58, they inhabit various habitat types. Acantholimon comprises cushion-forming subshrubs possessing linear acuminate leaves that grow in poor stony and gravelly soils or on exposed rocks59. Acanthophyllum represents perennial subshrubs that predominantly form cushions with spiny leaves that grow in steppe and mountain habitats on stony or sandy hills and rocky slopes43,60,61. The species of these two are mostly growing together in higher elevation ranges of KK indicating their similar ecological needs. The different features of these genera lie in their phenological periods and microhabitat preferences that might be the potential influencing elements leading to their various responses to climate change. Astragalus exhibits high morphological variation, including short-living annual herbs to perennial herbs forming spiny cushions that grow in semi-arid and arid areas62. Jurinea comprises a genus of herbs and subshrubs most of which are steppe elements that grow in dry habitats at higher elevations63. Thymus is a genus of perennial herbs or subshrubs that mainly inhabit mountainous steppes and meadows growing in stony or gravelly soil and on rocks64. Our findings highlight that all modeled genera will face habitat loss. The average range size change for the studied genera is -64.04 percent (Acantholimon), -35.90 percent (Acanthophyllum), -69.21 percent (Astragalus), -41.71 percent (Jurinea), and -90.88 percent (Thymus). Here, we observed that genera whose species have a wide distribution across the elevational ranges have the lowest risk of range contraction. While those who inhabit a narrower elevational range would experience greater range contraction risk. This pattern is observed in monitoring, modeling, and experimental studies17,65,66,67,68.

The majority of the endemic cushion species of the KK (22 out of 34) belong to the genera Acantholimon and Acanthophyllum (Supplementary 2). Members of these genera constitute essential cushions of the mountainous habitats of the KK. We modeled the response of eight Acantholimon and two Acanthophyllum species to climate change. Thus, further studies need to be conducted to examine how climate change will affect those species of Acantholimon and Acanthophyllum in the region that failed to be modeled by the present study.

A closer look at endemic cushions

Acantholimon

We modeled the response of eight endemic species of Acantholimon to climate change. The narrow-ranged A. alavae, is predicted to face extinction in the future (Fig. 2; Table 1). For this species, preserving genetic diversity through seed banks and botanical gardens is necessary. Additionally, planning assisted migration programs for A. gorganense, A. raddeanum, A. blandum in their gained habitats is recommended.

Acanthophyllum

Among the two endemic Acanthophyllum species modeled in our study, Ac. adenophorum will experience range contraction, while Ac. speciosum will show a negligible response in the future. A previous survey on Ac. squarrosum (an Irano-Turanian element) predicts that this species would experience a northward shift and gain new habitats in the coming decades30.

Astragalus

All of the four surveyed species will experience range contraction. (Table 1). For As. cystosus, As. hypsogeton, and As. raddei assisted migration to higher elevation or newly-gained habitats is necessary. Range contraction was also predicted for cushion-forming As. adscendens69, As. verus31, As. gossypinus70, As. nuratensis71, and As. variabilis72.

Jurinea

Seedling preservation and assisted migration is necessary to ensure the survival of J. kopetensis. Climate change has not yet been studied on other species of this genus in the Irano-Turanian region. Volis and Beshko71 reported that the climate space for J. zakirovii will be potentially suitable and translocation to predicted suitable habitats can conserve this endemic plant of Uzbekistan.

Thymus

Thymus transcaspicus is one of the highly sensitive species to climate change. Habitat preservation, along with botanical garden preservation, is necessary to ensure the survival of this cushion plant.

Conclusions

Cushions are ecosystem engineers in mountainous ecosystems, and altering their suitable habitats will completely modify the ecosystems. Our study provides insights into the possible responses of endemic cushions of the KK to climate change. All of the 19 cushions studied by the present research, will shift upward along their elevational range. Except for three, the rest of the examined species will face range contraction. We urge reinforcing the existing populations and implement fencing in various parts of these relatively disturbed mountain ranges. Effective conservation of the three highly vulnerable endemic cushions A. alavae, J. kopetensis and T. transcaspicus, is crucial. In the context of climate change, certain cushion species, i.e., A. restiaceum, Ac. speciosum and J. antunowi, appear to be minimally affected. To expedite the sustainable recovery of degraded mountainous landscapes in the KK region, we recommend the introduction of these climate-change-resilient species in their potentially suitable habitats. Future studies should include additional sampling of the endemic cushion species that we could not model their responses to climate change.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Pérez-Harguindeguy, N. et al. New Handbook for standardized measurment of plant functional traits worldwide. Aust. J. Bot. 61, 167–234 (2013).

Badano, E. I., Jones, C. G., Cavieres, L. A. & Wright, J. Assessing impacts of ecosystem engineers on community organization: A general approach illustrated by effects of a high-Andean cushion plant. Oikos 115, 369–385 (2006).

Zhang, Y.-Z. et al. Diversity patterns of cushion plants on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: A basic study for future conservation efforts on alpine ecosystems. Plant Divers. 44, 231–242 (2022).

Antonsson, H., Björk, R. G. & Molau, U. Nurse plant effect of the cushion plant Silene acaulis (L.) Jacq. in an alpine environment in the subarctic Scandes Sweden. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2, 17–25 (2009).

Butterfield, B. J. et al. Alpine cushion plants inhibit the loss of phylogenetic diversity in severe environments. Ecol. Lett. 16, 478–486 (2013).

Cavieres, L., Arroyo, M. T. K., Peñaloza, A., Molina-Montenegro, M. & Torres, C. Nurse effect of Bolax gummifera cushion plants in the alpine vegetation of the Chilean Patagonian Andes. J. Veg. Sci. 13, 547–554 (2002).

Reid, A. M., Lamarque, L. J. & Lortie, C. J. A systematic review of the recent ecological literature on cushion plants: Champions of plant facilitation. Web Ecol. 10, 44–49 (2010).

Erfanian, M. B. et al. Plant community responses to environmentally friendly piste management in northeast Iran. Ecol. Evol. 9, 8193–8200 (2019).

Niknam, P., Erfanzadeh, R., Ghelichnia, H. & Cerdà, A. Spatial Variation of Soil Seed Bank under Cushion Plants in a Subalpine Degraded Grassland. Land Degrad. Dev. 29, 4–14 (2018).

Molenda, O., Reid, A. & Lortie, C. J. The Alpine Cushion Plant Silene acaulis as Foundation Species: A Bug’s-Eye View to Facilitation and Microclimate. PLoS ONE 7, e37223 (2012).

Dullinger, S. et al. Extinction debt of high-mountain plants under twenty-first-century climate change. Nat. Clim Ch. 2, 619–622 (2012).

Wang, Y., Sun, J., Liu, B., Wang, J. & Zeng, T. Cushion plants as critical pioneers and engineers in alpine ecosystems across the Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Evol. 11, 11554–11558 (2021).

Watts, S. H. et al. Riding the elevator to extinction: Disjunct arctic-alpine plants of open habitats decline as their more competitive neighbours expand. Biol. Cons. 272, 109620 (2022).

Alnoiji, E. M., Erfanian, M. B., Atashgahi, Z. & Ejtehadi, H. Using multiple ecological evaluators to introduce a proper management plan for urban vacant lots: A case-study from Iran. Land Degrad. Dev. 34, 833–843 (2023).

Memariani, F. The Khorassan-Kopet Dagh Mountains. In Plant Biogeography and Vegetation of High Mountains of Central and South-West Asia (ed. Noroozi, J.) (Springer, 2020).

Arjmandi, A. A., Ejtehadi, H., Memariani, F., Mesdaghi, M. & Behroozian, M. Habitat characteristics, ecology and biodiversity drivers of plant communities associated with Cousinia edmondsonii, an endemic and critically endangered species in NE Iran. Commun. Ecol. 24, 201–214 (2023).

Erfanian, M. B., Sagharyan, M., Memariani, F. & Ejtehadi, H. Predicting range shifts of three endangered endemic plants of the Khorassan-Kopet Dagh floristic province under global change. Sci. Rep. 11, 9159 (2021).

Memariani, F., Zarrinpour, V. & Akhani, H. A review of plant diversity, vegetation, and phytogeography of the Khorassan-Kopet Dagh floristic province in the Irano-Turanian region (northeastern Iran–southern Turkmenistan). Phytotaxa 249, 8 (2016).

Atashgahi, Z., Ejtehadi, H., Mesdaghi, M. & Ghasemzadeh, F. Plant diversity of the Heydari Wildlife Refuge in northeastern Iran, with a checklist of vascular plants. Phytotaxa 340, 101–127 (2018).

Memariani, F., Joharchi, M. R. & Akhani, H. Plant diversity of Ghorkhod protected area NE Iran. Phytotaxa 249, 118–158 (2016).

Memariani, F., Joharchi, M. R., Ejtehadi, H. & Emadzade, K. A contribution to the flora and vegetation of Binalood mountain range, NE Iran : Floristic and chorological studies in Fereizi region. Ferdowsi Univ. Int. J. Biol. Sci. (J. Cell Mol. Res.) 1, 1–17 (2009).

Pashirzad, M., Ejtehadi, H., Vaezi, J. & Shefferson, R. P. Plant–plant interactions influence phylogenetic diversity at multiple spatial scales in a semi-arid mountain rangeland. Oecologia 189, 745–755 (2019).

Rahmanian, S. et al. Effects of livestock grazing on plant species diversity vary along a climatic gradient in northeastern Iran. Appl. Veg. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/avsc.12512 (2020).

Ferrarini, A., Dai, J., Bai, Y. & Alatalo, J. M. Redefining the climate niche of plant species: A novel approach for realistic predictions of species distribution under climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 671, 1086–1093 (2019).

Zurell, D. et al. A standard protocol for reporting species distribution models. Ecography 43, 1261–1277 (2020).

Erfanian, M. B., Barahoei, H., Zeynali, M. M. & Mirshamsi, O. Employing habitat suitability modeling to assess the distribution and envenomation potential of scorpion species in Iran. J. Med. Entomol. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjae151 (2024).

Hällfors, M. H. et al. Assessing the need and potential of assisted migration using species distribution models. Biol. Cons. 196, 60–68 (2016).

Behroozian, M., Ejtehadi, H., Peterson, A. T., Memariani, F. & Mesdaghi, M. Climate change influences on the potential distribution of Dianthus polylepis Bien. ex Boiss. (Caryophyllaceae), an endemic species in the Irano-Turanian region. PLoS ONE 15, e0237527 (2020).

Karimian, Z., Farashi, A., Samiei, L. & Alizadeh, M. Predicting potential sites of nine drought-tolerant native plant species in urban regions. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. https://doi.org/10.5073/JABFQ.2020.093.011 (2020).

Shamsabad, M. M., Assadi, M. & Parducci, L. Impact of climate change implies the northward shift in distribution of the Irano-Turanian subalpine species complex Acanthophyllum squarrosum. J. Asia-Pac. Biodivers. 11, 566–572 (2018).

Sheikhzadeh Ghahnaviyeh, A., Tarkesh Esfahani, M., Bashari, H. & Soltani Koupaei, S. and. Investigating geographical shifts of Astragalus verus under climate change scenarios using random-forest modeling (Case study: Isfahan and Chaharmahal va Bakhtiari provinces). Journal of Rangeland 15, (2021).

Erfanian, M. B., Ejtehadi, H., Vaezi, J. & Moazzeni, H. Plant community responses to multiple disturbances in an arid region of northeast Iran. Land Degrad. Dev. 30, 1554–1563 (2019).

Erfanian, M. B., Alatalo, J. M. & Ejtehadi, H. Severe vegetation degradation associated with different disturbance types in a poorly managed urban recreation destination in Iran. Sci. Rep. 11, 19695 (2021).

Djamali, M. et al. Application of the global bioclimatic classification to Iran: Implications for understanding the modern vegetation and biogeography. Ecologia mediterranea 37, 91–114 (2011).

Memariani, F., Akhani, H. & Joharchi, M. R. Endemic plants of Khorassan-Kopet Dagh floristic province in Irano-Turanian region: Diversity, distribution patterns and conservation status. Phytotaxa 249, 31 (2016).

Noroozi, J. et al. Hotspots within a global biodiversity hotspot - areas of endemism are associated with high mountain ranges. Sci. Rep. 8, 10345 (2018).

Arjmandi, A. A., Ejtehadi, H., Memariani, F., Joharchi, M. R. & Mesdaghi, M. Campanula oreodoxa (Campanulaceae), a new critically endangered species from the Aladagh Mountains NE Iran. Phytotaxa 521, 193–202 (2021).

Erfanian, M. B. et al. Unpalatable plants induce a species-specific associational effect on neighboring communities. Sci. Rep. 11, 14380 (2021).

Atashgahi, Z., Memariani, F., Polgerd, V. J. & Joharchi, M. R. Floristic composition and phytogeographical spectrum of Pistacia vera L. woodland remnants in northeastern Iran. Nordic J. Bot. https://doi.org/10.1111/njb.03510 (2022).

Flora of Iran, Vols. 1–77. (Research Institute of Forests and Rangelands Publications, Tehran, 1988).

Sadabadi, Z. M., Ejtehadi, H., Abrishamchi, P., Vaezi, J. & Noghan, E. T. M. B. Comparative study of autecological, morphological, anatomical and karyological characteristics of Acanthophyllum ejtehadii Mahmoudi & Vaezi (Caryophyllaceae): A rare endemic in Iran. Taiwania 62, 321–330 (2017).

Parishani, M. R., Rahiminejad, M. R., Mirtadzadini, M. & Saeidi, H. Chromosome numbers of taxa of the genus Jurinea Cass. (Asteraceae) in Iran. Caryologia 67, 86–95 (2014).

Pirani, A. et al. Systematic significance of seed morphology in Acanthophyllum (Caryophyllaceae: Tribe Caryophylleae) in Iran. Phytotaxa 387, 105–118 (2019).

Flora Iranica: Vols. 1–181. (Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt., Graz, 1963).

Thuiller, W., Georges, D., Engler, R. & Breiner, F. Biomod2: Ensemble Platform for Species Distribution Modeling. (2019).

Alavi, S. J., Ahmadi, K., Hosseini, S. M., Tabari, M. & Nouri, Z. The response of English yew (Taxus baccata L.) to climate change in the Caspian Hyrcanian Mixed Forest ecoregion. Reg. Environ. Ch. 19, 1495–1506 (2019).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315 (2017).

Abdelaal, M., Fois, M., Fenu, G. & Bacchetta, G. Using MaxEnt modeling to predict the potential distribution of the endemic plant Rosa arabica Crép. Egypt. Ecol. Inform. 50, 68–75 (2019).

Hijmans, R. J. Terra: Spatial Data Analysis. (2025).

Arredondo-Núñez, A., Badano, E. & Bustamante, R. How beneficial are nurse plants? A meta-analysis of the effects of cushion plants on high-Andean plant communities. Commun. Ecol. 10, 1–6 (2009).

Moradi, H., Noroozi, J. & Fourcade, Y. Plant endemic diversity in the Irano-Anatolian global biodiversity hotspot is dramatically threatened by future climate change. Biol. Cons. 302, 110963 (2025).

Petitpierre, B. et al. Will climate change increase the risk of plant invasions into mountains?. Ecol. Appl. 26, 530–544 (2016).

Zu, K. et al. Different range shifts and determinations of elevational redistributions of native and non-native plant species in Jinfo Mountain of subtropical China. Ecol. Ind. 145, 109678 (2022).

Borj, A. A. N., Ostovar, Z. & Asadi, E. The influence of climate change on distribution of an endangered medicinal plant (Fritillaria Imperialis L) in central Zagros. J. Rangel. Sci. 9, 159–171 (2019).

Khwarahm, N. R. Mapping current and potential future distributions of the oak tree (Quercus aegilops) in the Kurdistan Region Iraq. Ecol. Process 9, 56 (2020).

Rubidge, E. M. et al. Climate-induced range contraction drives genetic erosion in an alpine mammal. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2, 285–288 (2012).

Zu, K. et al. Upward shift and elevational range contractions of subtropical mountain plants in response to climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 783, 146896 (2021).

Kent, M. Vegetation Description and Data Analysis (John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2012).

Moharrek, F., Kazempour-Osaloo, S., Assadi, M. & Feliner, G. N. Molecular phylogenetic evidence for a wide circumscription of a characteristic Irano-Turanian element: Acantholimon (Plumbaginaceae: Limonioideae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 184, 366–386 (2017).

Pirani, A. et al. Molecular phylogeny of Acanthophyllum (Caryophyllaceae: Caryophylleae), with emphasis on infrageneric classification. Taxon 63, 592–607 (2014).

Pirani, A. et al. Phylogeny of Acanthophyllum s. l. revisited: An update on generic concept and sectional classification. Taxon 69, 500–514 (2020).

Azani, N., Bruneau, A., Wojciechowski, M. F. & Zarre, S. Molecular phylogenetics of annual Astragalus (Fabaceae) and its systematic implications. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 184, 347–365 (2017).

Szukala, A. et al. Phylogeny of the Eurasian genus Jurinea (Asteraceae: Cardueae): Support for a monophyletic genus concept and a first hypothesis on overall species relationships. Taxon 68, 112–131 (2019).

Jamzad, Z. Flora of Iran Lamiaceae Vol. 76 (Research Institute of Forests Rangelands, 2012).

Theurillat, J.-P. et al. Vascular Plant and Bryophyte Diversity along Elevation Gradients in the Alps. In Ecological Studies (eds Nagy, L. et al.) 185–193 (Springer, 2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-18967-8_8.

Alatalo, J. M. et al. Changes in plant composition and diversity in an alpine heath and meadow after 18 years of experimental warming. Alp. Bot. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00035-021-00272-9 (2021).

Alatalo, J. M. et al. Impact of ambient temperature, precipitation and seven years of experimental warming and nutrient addition on fruit production in an alpine heath and meadow community. Sci. Total Environ. 836, 155450 (2022).

Rosbakh, S., Bernhardt-Römermann, M. & Poschlod, P. Elevation matters: Contrasting effects of climate change on the vegetation development at different elevations in the Bavarian Alps. Alp. Bot. 124, 143–154 (2014).

Ghasemi, S., Malekian, M., Tarkesh, M. & Rezvani, A. Climate change alters future distribution of mountain plants, a case study of Astragalus adscendens in Iran. Plant Ecol. 223, 1275–1288 (2022).

Tarkesh, M. & Jetschke, G. Investigation of current and future potential distribution of Astragalus gossypinus in Central Iran using species distribution modelling. Arab. J. Geosci. 9, 80 (2016).

Volis, S. & Beshko, N. How to Preserve Narrow Endemics in View of Climate Change? The Nuratau Mountains as the Case. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-2816831/v1 (2023) https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2816831/v1.

Huang, R. et al. Predicting the distribution of suitable habitat of the poisonous weed Astragalus variabilis in China under current and future climate conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 921310 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Research Council of Ferdowsi University of Mashhad as a postdoctoral research project of the first author. We acknowledge the help of the botanists from the Herbarium of Ferdowsi University of Mashhad (FUMH).

Funding

Ferdowsi University of Mashhad.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z. Atashgahi: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis; M.B. Erfanian: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing; H. Moazzeni: Methodology, Writing – review & editing; G. Shemirani: Formal analysis; A. Pirani: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Atashgahi, Z., Erfanian, M.B., Moazzeni, H. et al. Endemic cushions of the Khorassan-Kopet Dagh floristic province show differential responses to future climate change. Sci Rep 15, 16046 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00453-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00453-0