Abstract

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) represent significant concerns for patients undergoing surgical procedures, as these symptoms greatly impact their postoperative experience. Among female patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery, the incidence of PONV is estimated to be approximately 45%. Moreover, for those individuals who have not undergone preventive treatment, the risk of experiencing PONV can be as high as 80%.Regrettably, despite ongoing efforts, there is still a lack of a fully effective and comprehensive solution to effectively manage and prevent PONV in these patient populations. The pursuit of an ideal strategy for the prevention and management of PONV remains an active area of research and clinical investigation. This prospective, single-center, randomized, double-blind study was conducted at Gansu Provincial Hospital from June 2021 to March 2022, involving a cohort of 100 subjects aged 18–65 years undergoing non-emergent gynaecological laparoscopic surgery. Prior to anesthesia induction, subjects were intravenously administered either 6.25 mg of promethazine or 1 mL of saline. Postoperatively, all subjects received patient-controlled intravenous analgesia and a continuous infusion of metoclopramide at a rate of 50 mg. The primary outcome measures included assessing the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting at 72 h following the surgical procedure. The results of this study show that the overall incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting within 72 h after operation is significantly different between the two groups before. (P = 0.026, P = 0.012). The incidence and severity of nausea during the early period (the first 6 h postoperatively) was significantly different between groups (P = 0.043, 95%CI(-0.273,-0.019), P = 0.048). A statistically significant difference was found in the incidence and severity within 24 h postoperatively (P = 0.026,95%CI (-0.348,-0.042), P = 0.003). Vomiting incidence and severity were lower than in the control group at the 6 h postoperatively but without statistical difference between the two groups (P = 0.166, 95%CI(-0.164,0.016) P = 0.180). Vomiting incidence and severity were statistically different during the 24 h postoperatively (P = 0.011, 95%CI(-0.342,-0.048),P = 0.004). A significant statistical difference was found in the satisfaction between the two groups during the postoperative observation period (P = 0.002). The administration of preoperative prophylactic promethazine proved to be notably effective in diminishing both the incidence and severity of postoperative nausea and vomiting within the initial 72 h postoperatively. This intervention demonstrated a favorable safety profile, characterized by a minimal occurrence of adverse effects and an absence of serious adverse reactions. Furthermore, the satisfaction levels of patients undergoing this prophylactic approach were observed to be improved. These findings highlight the potential benefits of preoperative prophylactic promethazine in enhancing the postoperative experience for patients, with positive implications for their overall satisfaction with the surgical procedure.

Clinical Trials Registration Number: (18/12/2021) ChiCTR2100054495.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) refers to the subjective experience of nausea, discomfort, and the expulsion of stomach contents through the mouth. This phenomenon typically manifests within the first 24 h postoperatively and, in some cases, may persist for up to 72 hours1,2. Identified risk factors associated with a heightened incidence of PONV encompass factors such as female gender, non-smoking status, a history of PONV, and the use of postoperative opioids. The incidence of PONV in female patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery is estimated to be around 40%3,moreover, the risk of PONV escalates to as high as 80% among patients who have not received prophylactic measures4. It is imperative to acknowledge the potential gravity of PONV, as it can lead to severe consequences, including aspiration, alkalosis, and notably, an increase in intra-abdominal pressure. The latter can result in critical adverse effects such as wound rupture and bleeding in patients undergoing abdominal surgery5These ramifications not only impede the prompt postoperative recovery of the patient but also elevate the overall medical burden, diminishing both their comfort and satisfaction6.

In 2016, the American Society for Enhanced Recovery issued an expert statement advocating that ‘All patients should receive prophylaxis for postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) in the perioperative period’7. However, the efficacy of current interventions remains constrained, as the incidence of PONV persists at nearly 30% despite multi-modal combined therapy8Promethazine, an antihistamine receptor representative drug, primarily exerts its anti-nausea and anti-vomiting effects through antihistamine activity, inhibition of emetic chemoreceptors in the medulla oblongata, anti-dopamine effects, and a moderate anticholinergic effect9Simultaneously, promethazine’s central anticholinergic properties allow it to influence the vestibule, vomiting center, and midbrain medullary receptors10 A study conducted by Bergese et al.11investigated the combination of promethazine with palonosetron and dexamethasone for the prevention of PONV, demonstrating a significant reduction in the incidence of PONV 24 h postoperatively. In the context of outpatient surgery, the use of 12.5 mg of promethazine in combination with metoclopramide proved effective in significantly reducing the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting12 However, it is worth noting that previous studies have associated some postoperative adverse reactions with the use of promethazine. Therefore, the objective of this prospective, randomized, double-blind trial was to explore the impact of promethazine on preventing PONV in high-risk patients and those undergoing gynecological laparoscopic surgery.

Methods

This prospective, randomized controlled, double-blind trial received approval from the Ethics Committee of Gansu Provincial Hospital in July 2021 (Approval No: 2021 − 231). Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients, and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study enrolled a total of 100 patients undergoing non-emergent gynecological laparoscopic surgery, aged between 18 and 65 years, with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status of I or II. Inclusion criteria also specified a body mass index within the range of 15–30 kg/m², a surgical duration of not less than 1 h, and an anticipated hospital stay exceeding 72 h. Exclusion criteria encompassed patients with asthma, mechanical intestinal obstruction, closed-angle glaucoma, a history of alcohol or opioid abuse, preoperative coma, psychiatric symptoms or intellectual disability, abnormal electrocardiograms, cardiovascular disease, and liver or renal insufficiency as identified in preoperative examinations. Pregnant or breastfeeding individuals and those currently enrolled in other studies were also excluded. To assess the risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), patients underwent preoperative evaluation using the simplified PONV score proposed by Apfel et al.13.

The concealment of allocation and the randomization process

The researchers used the computer-generated block randomization method: SAS 9.4 software was used to generate a random sequence, and the block size was set to 4 to ensure the balance between groups, and the random sequence was assigned to the experimental group and the control group according to the ratio of 1:1. The random sequence was generated by an independent statistician and sealed.

Allocation hiding mechanism:

We adopt the following strict measures to ensure that the allocation is hidden:

I: Use an opaque, sealed and continuously numbered envelope system.

II: The envelope shall be kept by the research coordinator.

III: only after the patient enters the operating room, it is turned on by the anesthesia nurse.

IIII: The envelope contains grouping information and corresponding number of study drugs.

Implementation details: Drug preparation was uniformly prepared by pharmacy. The experimental group: promethazine 6.25 mg/ml(4 ml), and the control group: normal saline 4 ml. Syringes with the same specifications were used with the same appearance. Blind method setting: patients, anesthesiologists and evaluators are blind, and only pharmacies and research coordinators know the grouping situation.

Quality control: regularly check the integrity of the random sequence, monitor the opening records of envelopes, and ensure that the drug distribution is consistent with the random sequence. Supervised by an independent data security monitoring committee.

Sample size calculation

Based on the previous research and pre-experiment, we set: main outcome measures: The incidence of PONV within 72 h after operation.

Expected incidence of control group: 45% [8](based on Apfel score and historical data of our hospital).

The expected incidence rate of the promethazine group: 20% (based on the preliminary experimental results).

α level: 0.05 (two-sided test), test efficiency (1-β): 0.80.

Sample size calculation:

Sample size calculation with PASS 15.0 software: Chi-square test was used to compare the proportions of the two groups, and it was calculated that 40 patients were needed in each group. Considering the 10% loss rate, 50 patients in each group were finally determined, with a total sample size of 100 patients.

Rationality statement:

I: It conforms to the sample size range of similar studies (usually 80–120 cases).

II: Clinically significant differences can be detected (20% absolute risk reduction).

III: Matching with the amount of operation in our hospital to ensure the feasibility of the study.

IV: It has passed the examination and approval of the Ethics Committee.

There were 41 patients in each group who were finally included in the study and analysis.

Outcom measures

The main outcome measure was the incidence of nausea and vomiting within 72 h after operation. The secondary outcome were extubation time and time of PACU, and other outcomes included VAS analgesia score, time out of bed, ventilation time, satisfaction, advers effects, length of stay, opioid consumption, Ramsay scores, Intraoperative blood loss.

The conduct of the trial

Preoperatively, patients observed fasting and did not receive any treatment before entering the operating room. Standardized anesthesia protocols were employed for both groups. Upon admission to the operating room, routine monitoring included electrocardiogram, non-invasive blood pressure, heart rate (HR), oxygen saturation, and bispectral index (BIS). Anesthesia induction involved intravenous administration of flurbiprofen ester at 50 mg, midazolam at 0.05 mg/kg, sufentanil at 0.4–0.6 ug/kg, etomidate at 0.15–0.3 mg/kg, and rocuronium at 0.6 mg/kg. Following induction, radial artery puncture was performed for invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring, and central venous pressure was monitored via the right internal jugular vein. Both groups received additional sufentanil at 0.5 µg/kg before excision to maintain BIS within the range of 40–60. Efforts were made to keep blood pressure fluctuations below 20% of the baseline value, and vasoactive drugs were administered if necessary. Atropine at 0.5 mg was administered for HR < 50 beats/min, and phenylephrine at 50–100 µg was administered if blood pressure fell by > 20% of the baseline value.

The formulation for the patient-controlled intravenous analgesia (PCIA) pump comprised nalbuphine at 50 mg, flurbiprofen at 200 mg, metoclopramide at 50 mg, and 0.9% normal saline at 150 ml for continuous infusion. The pump was programmed with an initial volume of 2 mL, a background continuous volume of 2 mL/h, a self-controlled volume of 2 mL, and a lock time set at 15 min.

Following surgery, patients were transferred to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) with a tracheal catheter in place. The depth of sedation and agitation during PACU admission was assessed using Ramsay scores. Additionally, data on extubation time and PACU stay were systematically documented. In order to more accurately evaluate the incidence and severity of nausea and vomiting within 72 h after operation, we chose four time points after operation: 6 h, 24 h, 48 h and 72 h. Nausea intensity was measured using a 5-point numerical rating scale (NRS: 1 = none, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = severe, or 5 = refractory). Vomiting was assessed using a scale (0 = no vomiting, 1–2 times/day = mild vomiting, 3–5 times/day = moderate vomiting, ≥ 6 times = severe vomiting). Patients requiring additional antiemetic intervention with dexamethasone and those receiving treatment for nausea and vomiting beyond 72 h, at the discretion of the clinician, were carefully documented. Pain levels were assessed 24 h postoperatively using a visual analogue scale (0 indicating no pain and 10 representing intolerable pain).

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 25.0 software is used for statistical analysis. The measurement data that conform to the normal distribution is expressed as the mean plus or minus standard deviation (x ± s), and the data description of the counting data adopts the percentage (%). The x2 test was used to compare the comparative data of the two groups, and the nonparametric test was used to test the severity of the grade data of the two groups. P-values of < 0.05 were considered a statistically significant difference.

Results

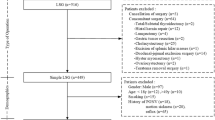

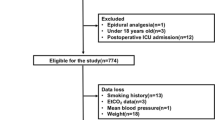

This study initially screened 100 patients, among whom 4 did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 2 declined participation in the study. Within the promethazine group, 1 patient received combined postoperative nerve block analgesia, and 5 encountered interruptions in their Patient-Controlled Intravenous Analgesia (PCIA). In the saline group, 2 patients received combined postoperative nerve block analgesia, and 4 experienced interruptions in their PCIA. Consequently, these patients were excluded from the analysis. Therefore, the data analysis encompassed 82 patients, with 41 participants in each group (as illustrated in Fig. 1). Upon comparison (referenced in Table 1), patient characteristics, operation duration, intraoperative access, PONV risk factors, and the type of surgery demonstrated no significant differences between the groups, indicating comparability.

Incidence and severity of PONV

The results of this study show that the overall incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting within 72 h after operation is significantly different between the two groups before. (P = 0.026, P = 0.012). The occurrence of nausea during the early postoperative period (first 6 h) was 4.9% in the promethazine group and 19.5% in the saline group, indicating significant differences between the two groups (P = 0.043,95%CI (−0.273,−0.019)). Additionally, the severity of nausea during the initial 6 h showed statistical distinctions between the groups (P = 0.048). A statistically significant variance was observed in the incidence within 24 h postoperatively (P = 0.026,95%CI (−0.348,−0.042)), with rates of 9.8% in the promethazine group and 29.3% in the saline group. Moreover, the severity of nausea within this 24-hour period exhibited statistically significant differences between the groups (P = 0.003). Regarding vomiting, the incidence was 2.4% lower in the promethazine group compared to the saline group at 6 h postoperatively, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.166), including the severity (P = 0.180,95%CI (−0.164,0.0166)). However, the incidence of vomiting was statistically different 24 h postoperatively (P = 0.011), with lower severity in the promethazine group compared to the saline group (P = 0.004,95%CI(−0.342,−0.048)) (refer to Table 2.).

In this study, we investigated the occurrence and intensity of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) at 48 h and 72 h postoperatively within the two groups. Among these parameters, only the incidence of nausea showed a significant difference at the 48-hour mark (P = 0.023), while the remaining variables did not exhibit statistical distinctions. Nevertheless, when considering the overall incidence of both nausea and vomiting, there were statistically significant differences between the two groups. (P = 0.026, P = 0.012) (Table 2.; Fig. 2).

PACU situation

The duration from the conclusion of the operation to the removal of the tracheal tube exhibited no statistically significant variance between the groups (P = 0.522), similarly to both the retention time (P = 0.362) and the Ramsay scores recorded in the PACU (P = 0.562). (Table 3).

Opioid consumption

There was no significant difference observed in the dosage of sufentanil during anesthesia induction, the intraoperative consumption of remifentanil, or the postoperative use of nalbuphine. (P = 0.604, P = 0.840, P = 0.464). (Table 4).

Postoperative ward situation

The durations of being out of bed and ventilation did not exhibit any significant differences between the groups (P = 0.714, P = 0.45). Additionally, there were no statistically significant variations in postoperative pain scores at 24 h, considering both rest and motion pain (P = 0.504, P = 0.13). Promethazine’s most common adverse reactions were sedation and drowsiness, with extrapyramidal reactions being the most severe. However, no significant difference was identified in sedation (P = 0.152), and no patients in either group reported experiencing drowsiness or extrapyramidal reactions. Furthermore, a statistically significant difference in satisfaction was noted between the two groups during the postoperative observation period. (P = 0.002) (Table 5).

Discussion

This study primarily demonstrated that administering preoperative prophylactic promethazine injections not only significantly decreases the incidence of nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing gynecological laparoscopic surgery at 0–48 h postoperatively but also has a notable ameliorated on the severity of nausea and vomiting at both 0–48 h and 6–24 h postoperatively.

Promethazine exhibits a broad spectrum of anti-nausea and anti-vomiting mechanisms, leading to notable effects, as outlined in several studies10, it is highlighted as a recommended medication in the latest guidelines for anti-nausea and anti-vomiting management. Furthermore, the pharmacological profile of promethazine includes a rapid onset of action, typically taking effect within 3–5 min after intravenous injection. The antihistamine properties generally endure for 6–12 h, while the sedative effects last for a period of 2–8 h. Given these characteristics, administering promethazine before anesthesia offers distinct advantages in the prevention of PONV.

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is defined as the occurrence of nausea, vomiting, or both within the initial 24 h postoperatively. The group administered with promethazine demonstrated a satisfactory preventive effect within the first 24 h. Additionally, there was a significant reduction in the incidence of PONV 48 h postoperatively, although the preventive impact at 24 h was more pronounced. Upon further analysis of the results, the correlation between the pharmacological characteristics of promethazine and its approximately 14-hour half-life was identified. This finding serves as a foundational element for the effective prevention of PONV during the early postoperative period. In comparison to a randomized controlled study conducted by D’souza et al., where in 4 mg of ondansetron was employed to prevent and treat PONV in gynecological laparoscopic surgery patients, our study reported a markedly lower incidence of PONV, specifically, 9.8% within the initial 24 h14.

Research indicates that the occurrence of PONV may extend up to 72 h following surgery15 In our study, we observed a low incidence of nausea in the promethazine group, particularly among patients who did not experience vomiting within the first 72 h. Several factors contributed to this outcome. Firstly, the early-stage reduction in PONV incidence can be attributed to the administration of preoperative preventive medication. Secondly, both patient groups received continuous treatment following metoclopramide administration. Additionally, each patient underwent postoperative patient-controlled intravenous analgesia (PCIA), contributing to a decrease in pain intensity, which, in turn, alleviates the occurrence of PONV. It is noteworthy that PONV primarily manifests within the initial 24 h postoperatively. Consequently, patients experiencing PONV should receive heightened attention during this critical period. Implementing preoperative preventive interventions proves to be effective in achieving optimal outcomes for the prevention and treatment of PONV.

In recent years, there have been limited studies examining the use of promethazine in preventing PONV. The clinical limitations of promethazine primarily stem from its potential for inducing adverse reactions, as identified in previous studies16However, despite these limitations, promethazine demonstrates a wide array of anti-nausea and anti-vomiting mechanisms with notable efficacy. Studies comparing the effects of promethazine at 6.25 mg and 12.5 mg revealed no discernible difference in their anti-nausea and anti-vomiting properties, with the 6.25 mg dosage showing rare occurrences of adverse reactions12 To mitigate the potential postoperative sedative effects associated with promethazine, we opted for a prophylactic intravenous injection of 6.25 mg preoperatively. This decision was made considering that the sedative impact of promethazine typically lasts between 2 and 8 h. We meticulously observed all patients in the Post-Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) and found no significant disparities between the two groups in terms of sedation scores, tracheal catheter removal time, or PACU retention time. Additionally, an analysis of opioid consumption between the two groups revealed no notable differences, thereby eliminating the possibility of opioids influencing postoperative sedation. Throughout the 72-hour postoperative period, two patients from the promethazine group reported experiencing dizziness. Further inquiry revealed that one of these patients experienced dizziness due to prolonged fasting, unrelated to the effects of promethazine. Both patients reported relief from dizziness within 12 h postoperatively, indicating that this outcome was not directly attributable to the administration of promethazine.

Apfel et al.13identified several high-risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), including female gender, a history of PONV or motion sickness, non-smoking, and postoperative opioid consumption. According to their findings, each of these risk factors contributes to a 20% increase in the overall risk of PONV, with female gender being the most potent risk factor17. Managing PONV in patients with these high-risk factors poses a notable clinical challenge. In our study, we specifically targeted patients undergoing gynecological laparoscopic surgery due to the absence of a clearly defined PONV regimen for this population. Previous research indicated a substantial incidence of PONV in these patients, ranging from 40–80%18,19. Surprisingly, our investigation revealed a significantly lower PONV incidence of only 9.8%. This marked reduction in PONV occurrence not only contributes to enhanced postoperative satisfaction but also facilitates the overall rehabilitation of patients in the postoperative period.

The concept of employing a combination of two or more drugs for the prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is referred to as multi-mode prevention and treatment. This approach is particularly advocated for high-risk patients. However, current investigations into this strategy have not yielded satisfactory results. Consequently, it becomes crucial to assess whether effective prevention, early reduction of PONV, and favorable perioperative outcomes can be achieved through alternative approaches.

Limitations

This study is subject to certain limitations. Firstly, the sample size is insufficient to fully capture potential adverse reactions arising from the concurrent use of the two drugs both before and after surgery. Secondly, the primary observational indicators are subjective in nature, introducing the possibility of a minor margin of error.

Conclusions

The administration of preoperative prophylactic promethazine in high-risk patients undergoing gynaecological laparoscopy, coupled with postoperative intravenous analgesia, demonstrated a significant reduction in both the incidence and severity of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) within the initial 72 h postoperatively. Importantly, this intervention resulted in few adverse effects and did not elicit any serious adverse reactions. Consequently, this approach contributed to heightened patient satisfaction. Based on these findings, the preoperative prophylactic administration of promethazine stands as a clinically recommended alternative for preventing PONV in the context of gynaecological laparoscopic surgery.

Data availability

“Raw data for dataset TABLES are not publicly available to preserve individuals’ privacy under the European General Data Protection Regulation”. “The data was acquired from researcher, and they have not given their permission for researchers to share their data. Data requests can be made to researcher via this email: 13893370700@163.com”.

Abbreviations

- PONV:

-

Postoperative nausea and vomiting

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anaesthesiologists

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- BIS:

-

Bispectral index

- PCIA:

-

Patient-controlled intravenous analgesia

- PACU:

-

Postanaesthesia care unit

References

Tateosian, V. S., Champagne, K. & Gan, T. J. What is new in the battle against postoperative nausea and vomiting? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 32, 137–148 (2018).

Bergese, S. D., Antor, M. A., Uribe, A. A., Yildiz, V. & Werner, J. Triple therapy with scopolamine, Ondansetron, and dexamethasone for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in moderate to high-risk patients undergoing craniotomy under general anesthesia: a pilot study. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 2, 40 (2015).

Som, A., Bhattacharjee, S., Maitra, S., Arora, M. K. & Baidya, D. K. Combination of 5-HT3 antagonist and dexamethasone is superior to 5-HT3 antagonist alone for PONV prophylaxis after laparoscopic surgeries: a meta-analysis. Anesth. Analg. 123, 1418–1426 (2016).

Darvall, J. et al. Interpretation of the four risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting in the apfel simplified risk score: an analysis of published studies. Can. J. Anaesth. 68, 1057–1063 (2021).

Kienbaum, P. et al. Update on PONV-What is new in prophylaxis and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting? Summary of recent consensus recommendations and Cochrane reviews on prophylaxis and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesist 71, 123–128 (2022).

Gan, T. J. Postoperative nausea and vomiting–can it be eliminated? JAMA 287, 1233–1236 (2002).

Gupta, R. & Soto, R. Prophylaxis and management of postoperative nausea and vomiting in enhanced recovery protocols: expert opinion statement from the American society for enhanced recovery (ASER). Perioper Med. 5, 4 (2016).

Apfel, C. C. & Roewer, N. Risk assessment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Int. Anesthesiol Clin. 41, 13–32 (2003).

Khalil, S. et al. Ondansetron/promethazine combination or promethazine alone reduces nausea and vomiting after middle ear surgery. J. Clin. Anesth. 11, 596–600 (1999).

Bergese, S. D. et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blinded, double-dummy pilot study to assess the preemptive effect of triple therapy with Aprepitant, dexamethasone, and promethazine versus Ondansetron, dexamethasone and promethazine on reducing the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting experienced by patients undergoing craniotomy under general anesthesia. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 3, 29 (2016).

Bergese, S. D. et al. The effect of a combination treatment using Palonosetron, promethazine, and dexamethasone on the prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting and QTc interval duration in patients undergoing craniotomy under general anesthesia: a pilot study. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 3, 1 (2016).

Gan, T. J. et al. Double-blind comparison of Granisetron, promethazine, or a combination of both for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in females undergoing outpatient laparoscopies. Can. J. Anaesth. 56, 829–836 (2009).

Apfel, C. C. et al. Evidence-based analysis of risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br. J. Anaesth. 109, 742–753 (2012).

D’Souza, N., Swami, M. & Bhagwat, S. Comparative study of dexamethasone and Ondansetron for prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting in laparoscopic gynecologic surgery. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 113, 124–127 (2011).

Laiq, N., Khan, M. N., Qureshi, F. A., Khan, S. & Jan, A. S. Dexamethasone as antiemetic during gynaecological laparoscopic surgery. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 15, 778–781 (2005).

Jo, S. H., Hong, H. K., Chong, S. H., Lee, H. S. & Choe, H. H(1) antihistamine drug promethazine directly blocks hERG K(+) channel. Pharmacol. Res. 60, 429–437 (2009).

Myklejord, D. J., Yao, L., Liang, H. & Glurich, I. Consensus guideline adoption for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting. WMJ 111, 207–213 (2012).

Simurina, T. et al. Effects of high intraoperative inspired oxygen on postoperative nausea and vomiting in gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. J. Clin. Anesth. 22, 492–498 (2010).

Lee, J. et al. Effect of adding Midazolam to dual prophylaxis for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. J. Clin. Med. ; 10. (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Yan for his theoretical and technical guidance during the whole trial. Thanks to the anesthesia team of Gansu Provincial Hospital and colleagues who participated in this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Liu Ruijuan participated in the design and conduct of the study, data analysis and writing the manuscript. Bi Ruirui participated in implementing of the study, data analysis. Zhang Jiqiang participated in implementing of the study, data analysis.Yan Wenjun participated in the design and conduct of the study, data analysis, and part of discussion and revision of the manuscript. Li Xia and Huang Jinwen participated in implementing of the study, data analysis. Su Yuxi participated in implementing of the study, data analysis.Zhang Yani participated in implementing of the study, data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Gansu Provincial Hospital. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruijuan, L., Jiqiang, Z., Ruirui, B. et al. Promethazine for nausea and vomiting prevention after gynaecological laparoscopic surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 16075 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00473-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00473-w