Abstract

Self-esteem is a stable characteristic that is usually maintained from adolescence to adulthood. People with high self-esteem are mentally prepared to face different challenges in their lives with great confidence. Assess the influence of dental aesthetics on self-esteem in students at the Polígono Sur Education Permanent Center. A cross-sectional descriptive study with qualitative and quantitative variables in which 92 participants from the permanent education center located in the polígono sur of the city of Seville. To identify if there was a relationship between self-perception of dental aesthetics and self-esteem, two surveys were conducted in the educational center, one of them to determine a high or low psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics and the Rosenberg self-esteem scale, which evaluated the level of acceptance and respect that participants had for themselves. Demographic variables analyzed were gender, age, nationality, and occupation. To analyze categorical variables, contingency tables and the Pearson Chi-square test were used. Students did not have a low self-esteem in relation to a high psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics p > 0, 05 (0.069), but a high self-esteem indifferent to whether they had a high or low psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics. However, there were exceptions according to gender (p = 0.019) or nationality (p = 0.030). Self-esteem was not greatly affected by the psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics in the majority of students evaluated, but it was possible to state that there was a negative impact in the male gender and also by nationality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Self-esteem is a stable trait that generally persists from adolescence to adulthood1. Reflects how we feel about ourselves and often helps us achieve what we desire. People with high self-esteem are mentally prepared to face various challenges in their lives with a strong sense of confidence2,3. The general concept of quality of life originated in the field of general medicine and has been defined as the perception of people of their position in life within the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, and standards4. Some oral diseases, such as cavities and periodontal disease, are among the most common and have an impact not only on aesthetics but also on social and psychological levels5. Self-concept is how each individual perceives themselves spiritually, physically, or socially. It can be acquired through experiences in society or through attributions one makes about his own behaviour6. The Oxford English Dictionary describes self-esteem as a good opinion of oneself; high self-esteem; confidence in one’s own worth or abilities, as well as in one’s own estimation or assessment of oneself7.

Self-esteem has also been defined as an internal attitude at the base of personality development, responsible for the psychological balance and adaptive processes of an individual throughout life8. William James first described it in 1890, as the extent to which people value their own qualities, linking it to the level of success or failure they may have achieved9. In people’s lives, physical appearance plays a very important role and dental aesthetics has a significant impact10. Perception of certain characteristics, such as colour, size, shape or position, can be psychologically important, even if there is no noticeable aesthetic or functional deterioration11. A physically attractive person is often perceived as more friendly, intelligent, extroverted and interesting; however, when there are anomalies in the oral cavity, such as cavities, missing teeth, or crowding, it can negatively affect the attractiveness and aesthetics of the smile12.

Despite significant improvements in population health throughout history, health disparities between subgroups persist, with poor health concentrated among socioeconomically marginalized groups. This trend is also evident in the oral health of these populations13. There is substantial evidence that social class strongly influences both morbidity and mortality rates14. Poor oral health is a reflection of socioeconomic inequalities, as well as low quality of life, is related to the health of families that are facing greater socioeconomic disadvantages, as it is difficult for them to access different dental services15. Low-income people, uninsured health care service, members of racial or ethnic minorities, rural populations, or immigrants, to this day, have received insufficient attention16.

This study was applied to students at the Permanent Center for Education of Poligono Sur (CEPER), most of whom are considered low-income individuals who were unable to complete their studies in time and summarizing them at the time of the surveys. This area of the city of Seville has a high rate of social inequality, and ndoubtedly, the quality of life is closely related to the oral health status of its residents17. The objective of this study is to analyze whether there is a relationship between self-esteem and dental aesthetics in CEPER students, as there are several studies that indicate that subjects affected by poor dental aesthetics in the psychosocial domain cannot develop adequately in the social area and tend to be more introverted18. Consequently, the proposed conceptual hypothesis was as follows: Dental aesthetics influences the self-esteem of students.

Materials and methods

Design and type of study

A descriptive-analytical study, with qualitative and quantitative variables, was carried out using two surveys, the psychosocial impact questionnaire on dental aesthetics (PIDAQ) and the Rosenberg self-esteem scale, through which the data obtained were described and analyzed. Both surveys consist of multiple-choice questions utilizing a deductive-inductive method. It was determined whether there is a correlation between the perception of dental aesthetics and the self-esteem of the students at CEPER in the city of Seville in April 2024.

Study location

The Polígono Sur of Seville is currently categorized as one of the areas with the highest rates of poverty and social conflict in the Spanish territory; it faces serious problems of a social, urban, and environmental nature. Through statistical references, analyses carried out in various studies and reports, as well as the very configuration of its urban environment, it is clearly evident that it is one of the most extreme cases of urban inequality in Spain. The marked disadvantages it is currently experiencing have their origin in the concentration of impoverished population, which arose as a result of the original urban project: a social housing estate located on the outer edge of the city, built between the decades of the 1960s and 1970s, where numerous humble families from different backgrounds were relocated, evicted from historic neighbourhoods, or from precarious settlements such as slums, shelters, and substandard housing. This sector of the population suffers more intensely from different moments of crisis and, unfortunately, has been neglected by the authorities for long periods19.

Psychosocial impact of dental aesthetic questionnaire (PIDAQ)

This questionnaire has been used in previous studies and was originally developed in English by Klages et al. in 200620. The spanish version of the PIDAQ survey was validated by Montiel et al. in 2013, maintaining an internal structure and psychometric properties closely aligned with the original Klages questionnaire. It is designed to assess individual satisfaction with the appearance of their teeth. It is divided into five domains: Dental self-esteem and self-confidence, social impact, psychosocial impact, aesthetic considerations, and patient beliefs. This assessment includes 23 items with a 5-point Likert scale, offering five response options: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree. Items were grouped into one positive subscale, self-confidence in dental appearance (6 items), and three negative subscales: psychological impact (6 items), social impact (8 items), and aesthetic concern (3 items). A total score can range from 0 to 92 points. Scores of 0 to 46 indicate a low impact, while scores of 47 to 92 reflect a high psychosocial impact on the individual.

Rosenberg self-esteem scale

The Rosenberg self-esteem scale, created by psychologist Morris Rosenberg in 1965, is widely used to assess self-esteem across all age groups. The scale consists of ten items, with five positively worded statements and five negatively worded ones. Its purpose is to measure the level of self-acceptance and self-respect among individuals. Responses are given on a four-point Likert scale with the following options: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree and 4 = strongly agree. For items 1 to 5, responses A to D, are scored from 4 to 1. For items 6 to 10, responses A and D, are scored from 1 to 4. Scores of 30 to 40 points indicate high self-esteem and are considered within a normal range. Scores between 26 and 29 reflect moderate self-esteem, suggesting that there are no serious problems, but there is a place to improve, while scores below 25 indicate significant self-esteem issues21,22.

Data processing and analysis techniques

Once surveys were conducted and information collected, the data were classified by gender, age, nationality, and occupation. The results were compiled in an Excel data sheet, after which the SPSS software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) was used to generate charts and tables for analysis, allowing the interpretation of the gathered information. In order to analyse categorical variables, contingency tables and the Pearson´s Chi-square test were used. The level of significance was established at p < 0.005.

Results

The total number of students at CEPER was 408. The study population included was 92 participants from the morning and afternoon sessions at CEPER, the mean age of the students who completed the questionnaire was 26.22 with a SD of 12.10, their ages were distributed between 16 and 79 years, of which 43.5% were male and 56.5% were female. Inclusion criteria established to select the sample were; students who were about to enter the workforce or were already employed and in regular interaction with society, students who have agreed to participate in the research, and students of any gender, nationality, and age. The only exclusion criterion was those students who did not regularly attend their classes at CEPER Polígono Sur. In Table 1 it is possible to observe the distribution of participants according to their demographic characteristics. Based on occupation, they were divided into four categories: 68 were students, seven were homemakers, 14 worked in customer service and three were involved in construction and trade. The male gender group included 40 participants, and the female group included 52 participants. According to age, the population studied included 78 young students, 12 adults and two seniors, nationalities of participants were grouped by continental origin, with 62 spanish citizens, 15 latin-americans and 15 Africans.

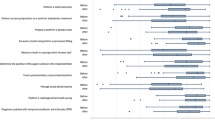

In Table 2 shows that the association between low self-esteem and low psychosocial impact was zero (0), while the relationship between high self-esteem and low psychosocial impact was 49 (49), with a p-value greater than 0.05 (p = 0.69).

In Table 3, two men were recorded to have low self-esteem, while 40 women had high self-esteem, with a p-value of 0.019, indicating statistically significant differences. In the group that included male participants, 26 reported a low psychosocial impact, while 23 of female gender reported a high psychosocial impact. However, with a p-value of 0.371, there was no statistically significant relationship between psychosocial impact and gender. Among the students in the youth group, 68 had high self-esteem, while no senior participant had low self-esteem. According to the p-value (0.040), there was a statistically significant relationship between age and self-esteem. It was observed that 52 young participants were found to have a low psychosocial impact, while 10 adult participants had a high psychosocial impact. According to the p-value (0.004), there was a statistically significant relationship between age and self-perception of dental aesthetics.

Within the group of participants with Spanish nationality, 56 participants had high self-esteem, while two participants from Africa had low self-esteem. According to the p-value (0.03), there was a statistically significant relationship between self-esteem and nationality. It was observed that 43 Spanish participants were observed to have a low psychosocial impact, while ten participants of Latin American origin had a high psychosocial impact. According to the p-value (0.020), there was a statistically significant relationship between nationality and self-perception of dental aesthetics. Based on occupation, it was observed that 58 participants in the student group had high self-esteem, six homemakers had high self-esteem, ten people who provide customer service had high self-esteem, and two individuals in construction and commerce had high self-esteem, while only two students had low self-esteem. According to the p-value (0.690), there was no statistically significant relationship between occupation and self-esteem. It was observed that 46 students were found to have a low psychosocial impact, five homemakers had a high psychosocial impact, nine participants who provide customer service had a high psychosocial impact, and two participants who work in construction and commerce had a low psychosocial impact. According to the p-value (0.046), there was a statistically significant relationship between occupation and self-perception of dental aesthetics.

Discussion

Currently, facial aesthetics has become an increasingly central factor in the life of every individual. The lower third of the face, and more specifically dental aesthetics, plays a key role in this aspect, as it is one of the features that most captures the observer’s attention. This has led to a significant increase in the demand for dental treatments for aesthetic purposes, with the final objective in many cases of improving self-esteem. The association with dental aesthetics and self-esteem, such as the good aesthetics of a smile, can contribute to psychosocial well-being and oral quality of life23. It is possible to affirm that the appreciation of the beauty of a smile encompasses multiple subjective aspects, where many external variables could come into play, such as age, gender, nationality, or occupation. By comparing the results of the PIDAQ and Rosenberg surveys (p = 0.069), there was no statistically significant association between variables studied. This suggests that, in this study, self-perception of dental aesthetics and self-esteem were not associated. It is evident that most of the participants did not express significant interest in the appearance of their teeth, experiencing a low psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics while maintaining high self-esteem. These results contradict the study by Anshika Sharma et al. in 2017, when they evaluated adolescents between 10 and 17 years of age from Sri Ganganagar, Rajasthan, India, who found that of the 1140 adolescents studied, 56.9% of dental disorders had a high impact on self-esteem, as dental aesthetics plays an important role in development and life24.

Self-esteem was associated with gender in the present study, due to the p-value obtained (0.019), which indicates statistically significant differences. However, with a p-value of 0.371, there was no statistically significant relationship between psychosocial impact and gender. This means that in this study, self-perception of dental aesthetics was not associated with gender. These results contradict a study conducted by Stojilković M. et al. in 2024, they studied 410 participants, 80% of whom were women aged 20 to 23 years, that study showed a significant relationship between PIDAQ scores and age; Students who experienced a greater psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics tended to have lower self-esteem25. A study conducted by Lukez A. et al. in 2015 supports the connection between these variables. They included a total of 155 individuals, of which 36% were men aged 12 to 39 years. They found that the female gender is associated with a greater psychological influence of dental aesthetics, while the male gender and advanced age were associated with self-esteem. They concluded that it seems that people are less focused on the details of their smile and more on the distinctive misalignment of their teeth26. Among the students according to the p-value (0.040), there was a statistically significant relationship between age and self-esteem. In young participants, they were observed to have a low psychosocial impact, while in the adult group, participants had a high psychosocial impact. According to the p-value (0.004), there was a statistically significant relationship between age and self-perception of dental aesthetics. A study conducted by Veneté A. et al. in 2017, with a sample of 301 students from the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry of the University of Valencia, aged 18 to 30, found that the students most affected by poor dental aesthetics exhibited lower self-esteem and higher levels of perfectionism26.

According to the p-value (0.03), there was a statistically significant relationship between self-esteem and nationality. According to the p-value (0.020), there was a statistically significant relationship between nationality and self-perception of dental aesthetics. Our results are consistent with those obtained by Mazen et al., who conducted a study in 2023 with the purpose of comparing the perception of upper dental midline deviation on the attractiveness of a smile among evaluators from different ethnicities, professions, genders, and ages, and measuring to what extent the presence or absence of the associated smiling structures influences the raters’ evaluations. They found statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between the two ethnicities studied and concluded that the perception of upper dental midline deviations was influenced by factors of ethnicity, profession, presence or absence of structures associated with smiles, as well as the gender and age27. In contrast, Niaz et al., who conducted a study in 201528 and found no association between ethnicity and attitudinal score was found. There were strong correlations between the value of the tooth shade self-assessed and professionally assessed in all ethnic groups, with the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (rho) being ρ > 0.6. Regarding the ideally desired and perceived value of the tooth shade, weak correlations were found in all ethnic groups (Spearman’s rho being ρ < 0.4). According to the p-value (0.690), there was no statistically significant relationship between occupation and self-esteem. According to the p-value (0.046), there was a statistically significant relationship between occupation and self-perception of dental aesthetics. These results may contradict the study conducted by Alqarawi et al. in 202429, which was carried out with dental students from various dental schools in Karachi, Pakistan, from January to May 2022. Evaluation of the psychological aspect and self-esteem of the students was conducted using the PIDAQ and Rosenberg self-esteem scale as perceived by the students during the covid pandemic. Social impact showed a significant association with psychological impact, aesthetics concern, and self-esteem, while negatively correlated with dental confidence. The Rosenberg score showed a positive correlation with all variables.

Once the surveys were completed and the statistical analysis of the results was conducted, we can state that this study presented several limitations during its development, such as: limitations regarding the calculation and sample size, as the participants were all students from the educational institution who met the inclusion criteria; time limitations, as this study was methodologically designed as a cross-sectional study, with the development framed within the participants’ school schedule and the academic year of the examiner who applied PIDAQ and Rosenberg surveys. Finally, it is possible that confounding variables not taken into account may have interfered with the data analysis, such as the number of visits to the dentist per year, oral health status, mental and physical health status, social status, or academic performance, according to the perception of dental aesthetics. We should be able to conduct prospective studies in which surveys would be possible before and after interventions, which must include awareness campaigns about oral health. As a final consideration, it is essential that oral health professionals understand different concepts such as self-perception, self-esteem, and the psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics, and perceive needs and feelings of their patients in relation to these variables.

Conclusions

Once the results obtained have been analyzed, according to the objectives set out in this study, we can conclude that most of participants had high self-esteem and a low psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics, suggesting that the appearance of the teeth did not affect their self-esteem. In relation to gender, it can be concluded that in this study men were more affected by their self-esteem in relation to dental aesthetics. According to age, dental aesthetics did not influence self-esteem. African students, expressed low self-esteem and high psychosocial impact, finally there was a statistically significant relationship between occupation and self-perception of dental aesthetics.

Data availability

Data availability: The datasets used during the current study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Twigge, E., Roberts, R. M., Jamieson, L., Dreyer, C. W. & Sampson, W. J. The psycho-social impact of malocclusions and treatment expectations of adolescent orthodontic patients. Eur. J. Orthod. 38 (6), 593–601. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjv093 (2016).

Paz, V. et al. Effect of self-esteem on social interactions during the ultimatum game. Psychiatry Res. 252, 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.12.063 (2017).

Apolo Morán, J. & Miranda, V. L. Y Rivas Maldonado, N. Psicología Clínica Aplicada a La Odontología (Grupo Compas. Guayaquil, 2017).

Marcelo-Ingunza, J. et al. Calidad de Vida relacionada a La Salud bucal En escolares de Ámbito urbano-marginal. Revista Estomatológica Herediana. 25 (3), 194–204 (2015 jul). http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext &pid=S1019-43552015000300004&lng=es.

Chakradhar, K. et al. Self perceived psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics among young adults: a cross sectional questionnaire study. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health. 32 (3). https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2017-0129 (2017).

Fuentes, M. C., García, J. F., Gracia, E. & Lila, M. Autoconcepto y ajuste psicosocial en la adolescencia. Psicothema, 2011; 23(1), 7–12. PMID: 21266135. (2011).

AlHarbi, N. Self-Esteem: A concept analysis. Nurs. Sci. Q. 35 (3), 327–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/08943184221092447 (2022).

Doré, C. L’estime de Soi: analyse de concept. Rech Soins Infirm. 1 (129), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.3917/rsi.129.0018 (2017).

Enrique, M. & Muñoz, R. El problema de La autoestima Basado En La eficacia. Ed. PSOCIAL. 1, 1 (2014).

Da Silva, F. B., Chisini, L. A., Demarco, F. F., Horta, B. L. & Correa, M. B. Desire for tooth bleaching and treatment performed in Brazilian adults: findings from a birth cohort. Braz Oral Res. 32, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-3107bor-2018.32.0012 (2018).

Campos, L. A., Costa, M. A., Bonafé, F. S. S., Marôco, J. & Campos, J. A. D. B. Psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics on dental patients. Int. Dent. J. 70 (5), 321–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/idj.12574 (2020).

Samsonyanová, L. & Broukal, Z. A systematic review of individual motivational factors in orthodontic treatment: facial attractiveness as the main motivational factor in orthodontic treatment. Int. J. Dent. 2014, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/938274 (2014).

Chari, M. et al. Oral health inequality in Canada, the United States and United Kingdom. Denis F, editor. PLOS ONE. ; 17(5):e0268006. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268006

Medina-Solís, C. E. et al. Desigualdades socioeconómicas En Salud Bucal: caries dental En Niños de seis a 12 Años de edad [Socioeconomic inequalities in oral health: dental caries in 6 to 12 year-old children]. Rev. Invest. Clin. 58 (4), 296–304 (2006). PMID: 17146941.

Chaffee, B. W., Rodrigues, P. H., Kramer, P. F., Vítolo, M. R. & Feldens, C. A. Oral health-related quality-of-life scores differ by socioeconomic status and caries experience. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 45 (3), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268006 (2017).

Northridge, M. E., Kumar, A. & Kaur, R. Disparities in access to oral health care. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 41 (1), 513–535. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094318 (2020).

Kavaliauskienė, A., Šidlauskas, A. & Zaborskis, A. Association between global life satisfaction and Self-Rated oral health conditions among adolescents in Lithuania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 14 (11), 1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14111338 (2017).

Castaño Seiquer, A. & Ferreira Cabañas, A. Peniche Marcín R. Programas De Odontología Social (Ed Autografía Barcelona, 2024).

Gutiérrez Francisco José Torres. Polígono Sur en Sevilla. Historia de una marginación urbana y social. Scripta Nova. Revista Electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales. ; 25 (2). (2021).

Klages, U., Claus, N., Wehrbein, H. & Zentner, A. Development of a questionnaire for assessment of the psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics in young adults. Eur. J. Orthod. 28 (2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cji083 (2006).

Wood, C., Griffin, M., Barton, J. & Sandercock, G. Modification of the Rosenberg scale to assess Self-Esteem in children. Front. Public. Health. Jun 17 (9). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.655892 (2021).

Simbaña Ninahualpa, Z. P., Macías Ceballos, S. M. & López Ríos, E. F. Prevalencia de maloclusión y Necesidad de Tratamiento Ortodóntico e impacto psicosocial de La estética dental En adolescentes. Odontología (Lima). 25 (1), 7–16 (2023).

Sharma, A. et al. Objective and subjective evaluation of adolescent’s orthodontic treatment needs and their impact on self-esteem. Rev. Paul Pediatr. 35 (1), 86–91. https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-0462/;2017;35;1;00003 (2017). Avaliação Objetiva E Subjetiva Da Necessidade De Tratamento Ortodôntico Do Adolescente E Seu Impacto Sobre A Autoestima.

Stojilković, M. et al. Evaluating the influence of dental aesthetics on psychosocial well-being and self-esteem among students of the university of Novi sad, Serbia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 24 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04002-5 (2024).

Lukez, A., Pavlic, A., Trinajstic Zrinski, M. & Spalj, S. The unique contribution of elements of smile aesthetics to psychosocial well-being. J. Oral Rehabil. 42 (4), 275–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12250 (2015).

Venete, A. et al. Relationship between the psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics and perfectionism and self-esteem. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 9 (12), e1453–e1458. https://doi.org/10.4317/jced.54481 (2017).

Musa, M. et al. Effect of the ethnic, profession, gender, and social background on the perception of upper dental midline deviations in smile esthetics by Chinese and black raters. BMC Oral Health. 23, 214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-02893-4 (2023).

Niaz, M. O., Naseem, M. & Elcock, C. Ethnicity and perception of dental shade esthetics. Int. J. Esthet Dent. 10 (2), 286–298 (2015 Summer). PMID: 25874275.

Alqarawi, F. K. et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the self-esteem, psychological and dental esthetics of dental students. Work 7 7 (2), 407–416. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-220627 (2024).

Funding

This research did not receive external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization D.R-P, E R-G and A CS , methodology and writing D R-P, A DF and M A R, original draft preparation writing A DF and M AR , review, and editing D R-P, J TM, L E M , A C-S and M AR, visualization, L E M and J TM; supervision, E R-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Signed informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection began, explaining the purpose and nature of the study and guaranteeing that they could leave the study at any time without facing repercussions.

Ethical statements

In the conduct of this investigation, the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed. Participants were informed of the purpose of the study and the voluntary nature of their participation. They were informed that their responses would not affect their learning at CEPER, given the anonymous nature of data processing. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Social Dentistry Foundation (FOS) under registration number 03/2024.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fernández-Cevallos, A.D., Ribas-Perez, D., Arenas-González, M. et al. Impact of dental aesthetics on self-esteem in students at the Polígono Sur education permanent center in Seville, Spain. Sci Rep 15, 15550 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00545-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00545-x