Abstract

Introduction Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting PD-1 and PD-L1 have emerged as promising treatments for advanced NSCLC patients without actionable mutations. However, predicting treatment response remains challenging, especially in second-line settings. Although PD-L1 is the only validated biomarker, additional prognostic tools are needed. Systemic inflammation markers such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) show potential but remain underused. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), linked to immunotherapy resistance, are associated with increased splenic volume. Therefore this study introduces a splenic index score, combining pre-immunotherapy splenic volume and NLR, to evaluate its prognostic value in NSCLC patients treated with nivolumab in the second-line setting. We analyzed 50 patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who received nivolumab as second-line or later therapy. Baseline splenic volume and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) were assessed using imaging and laboratory data prior to nivolumab initiation. The Splenic Index Score for each patient was calculated using the formula: (baseline splenic volume) × (NLR). Additionally, we evaluated the impact of other factors, including body mass index (BMI), tumor PD-L1 expression, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, and sites of metastasis. The median Splenic Index score was 877.3 (range: 180–4830). A higher Splenic Index score was significantly associated with worse overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) (p = 0.001 and p = 0.03, respectively). Specifically, patients with a high Splenic Index score had a median PFS of 3 months, compared to 8 months in those with a low Splenic Index score (HR 1.96, 95% CI 1-3.7, p = 0.03). Similarly, the median OS was 4 months for patients with a high Splenic Index score, while it was 15 months for those with a low score (HR 3.5, 95% CI 1.6–7.3, p = 0.001). Baseline splenic volume, basal NLR, and tumor PD-L1 expression were also evaluated; however, no significant differences in PFS or OS were observed for these parameters. Our study demonstrates that the splenic index score, derived from combining radiological and peripheral inflammatory biomarkers, serves as a predictive tool for progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in metastatic NSCLC patients receiving second-line nivolumab therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent improvements in immunotherapy have introduced immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting the programmed cell death receptor-1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) as promising treatment strategies for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients who lack actionable genetic mutations1. Despite the potential of these therapies, predicting responses to ICIs remains a significant challenge, particularly in second-line treatments, where the need for reliable prognostic tools is even more pronounced. Although extensive research has identified numerous complex biomarkers, PD-L1 is currently the only validated and accessible biomarker used in clinical practice. Additionally, there is a notable gap in research regarding the clinically applicable biomarkers that can be seamlessly integrated into routine clinical care2.

Blood tests reflecting systemic inflammation, such as neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), have emerged as prognostic indicators in various cancers, including NSCLC3,4. The predominance of neutrophils coupled with low lymphocyte levels is indicative of a non-specific acute inflammatory response. Consequently, the NLR has been extensively studied as a potential predictive or prognostic factor across multiple cancer types3,5. Despite its accessibility, affordability, and ease of interpretation, NLR remains underutilized as a prognostic tool in clinical settings.

In recent years, the role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in immunotherapy resistance has gained increasing attention. MDSCs are a heterogeneous population of immature, immunosuppressive myeloid progenitor cells. Their accumulation is observed in the spleen, circulation, and tumor microenvironment of cancer patients6. Although specific genomic signatures and markers for MDSCs have been identified, clear clinical indicators for these cells are still lacking.

The spleen plays a critical role in hematopoiesis and immune regulation, making it a valuable organ for assessing the efficacy of immunotherapy. Animal studies have shown that increased MDSCs can lead to splenomegaly, and some clinical studies have correlated MDSC levels with splenic volume7,8. Changes in splenic volume have been associated with survival outcomes in a retrospective analysis of NSCLC patients9. However, despite its simplicity and practicality, splenic volume measurement remains underutilized as a prognostic tool in clinical practice.

In the current study we calculated the splenic index score by multiplying the splenic volume with the NLR prior to the start of immunotherapy and we hypothesize that this composite score could serve as an indirect marker of immunotherapy resistance.

Therefore, our study aims to assess the combined impact of splenic volume and the NLR, formulated as the splenic index score, in advanced NSCLC patients treated with nivolumab as second-line therapy.

Materials and methods

Study design

This retrospective study examines the relationship between the Splenic Index score, assessed before the initiation of immunotherapy, and survival outcomes in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Each patient’s Splenic Index Score was calculated using the formula: Splenic Index Score = (Basal Splenic Volume) × (NLR). Patients were then stratified based on the respective median baseline level into high (> median) and low (≤ median).

The analysis included only those patients who had measurable splenic volume at the baseline of nivolumab treatment. Splenic volume was measured prior to the initiation of nivolumab. PD-L1 expression was evaluated using the PD-L1 IHC 22C3 assay (Dako), with TPS representing the percentage of tumor cells exhibiting membrane staining.

Between 2010 and 2023, 50 patients who received nivolumab as second - or third-line therapy after previous systemic chemotherapy were included in the study. This study was approved by the Gazi University Ethics Committee on December 13, 2023 (Approval No: 27b4ab49-d82f-413f-8878-ad4fd24f4115). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Gazi University Ethics Committee waived the requirement for obtaining informed consent.

Study population and data

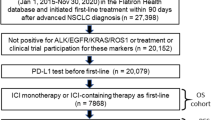

The study enrolled adult patients with histologically confirmed metastatic NSCLC. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans were conducted within one month prior to the initiation of nivolumab therapy. Patients with conditions that could influence splenic volume and NLR, including autoimmune disorders, chronic liver disease, or systemic infections, were excluded from the study population. Specifically, patients with known infectious diseases were not considered for inclusion (Fig. 1). Clinical and laboratory assessments, including the determination of the absolute neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), were performed before the first nivolumab dose. Patients were then stratified based on the respective median baseline level into high (> median) and low (≤ median). BMI categories were defined according to the World Health Organization classification: <25 kg/m2 (normal), 25–29.9 kg/m2 (overweight), and ≥ 30 kg/m2 (obese)10.

Spleen volume estimation

Baseline splenic volume was assessed using imaging conducted within within one month prior to the initiation of nivolumab therapy. A highly experienced radiologist, with 20 years of expertise and blinded to the clinical outcomes, performed measurements on axial and coronal reformatted CT images. The splenic volume was determined using a formula developed by Prassopoulos P. et al. (ref): V = 30 + 0.58 (W × L × T), where W is the maximal width of the spleen at the hilum, T is the maximum thickness at the hilum perpendicular to W, and L is the maximal caudocranial length11.

Evaluation and statistical analyses

The sample size was calculated using the G*Power 3.1.9.4 software, considering the significance level of the hypothesis and the effect size. Based on the hazard ratio (HR) reported in the study by Galland et al.9, where having a baseline Volume > 194 mL increased the risk of mortality by 2.6 times (HR: 2.6, 95% CI 1.40–4.90, p = 0.002), the minimum required sample size was determined to be 11 when α = 0.05 and power (1-β) = 0.95.

Correlation analysis was conducted using the Spearman method to assess the relationships between variables.

Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of the first nivolumab dose until death from any cause, whereas progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from the initiation of nivolumab to either disease progression, death, or the last recorded outpatient clinic visit. Radiological responses were evaluated according to RECIST version 1.1 criteria. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method, with comparisons made via log-rank tests. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were utilized to determine hazard ratios (HRs) and to identify independent predictors of OS and PFS in patients with metastatic NSCLC. A p value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance, whereas p values ≥ 0.05 and < 0.1 were considered statistical trends.

Results

Patient characteristics

Fifty patients met the recruitment criteria and were included in this study. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are demonstrated in (Table 1). The median splenic index was 877.3, the median baseline splenic volume was 214 mL (range: 114–489 mL), and the median NLR was 3.70.

In the correlation analysis, no significant relationship was found between basal splenic volume (mL) and age (r=-0.297, p = 0.057) or body mass index (BMI) (r = 0.286, p = 0.054) in males. Similarly, no significant relationship was observed between basal splenic volume (mL) and age (r = 0.000, p = 1.000) or BMI (r=-0.725, p = 0.165) in females (Figs. 2 and 3). All patients had undergone at least one prior line of chemotherapy before starting nivolumab. Nivolumab was administered intravenously at a dose of 3 mg/kg every two weeks.

Survival and prognosis

The results of our univariate and multivariate analyses for overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) are presented in Tables 2 and 3. In the univariate analysis, the splenic index score was significantly associated with OS (p = 0.001). Although neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), PD-L1 expression, and body mass index (BMI) did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.17, 0.28 and 0.05, 0.90 respectively), they were included in the multivariate analysis alongside the splenic index score due to their clinical relevance. In the multivariate analysis, only the splenic index score remained a significant predictor of OS (p = 0.008) (Table 2). The splenic index score was also associated with PFS in univariate analysis (p = 0.03) (Table 3).

The median overall survival (mOS) for patients with a high splenic index score was 4 months, compared to 15 months for those with a low splenic index score (HR = 3.5, 95% CI 1.6–7.3, p = 0.001). Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for these two groups.

The median progression-free survival (mPFS) was 3 months for patients with a high splenic index score, compared to 8 months for those with a low splenic index score (HR = 1.96, 95% CI 1.0–3.7, p = 0.03). Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for these two groups.

The NLR was analyzed independently; however, neither progression-free survival (PFS) nor overall survival (OS) showed a significant difference (Figs. 6 and 7).

PD-L1 expression was evaluated, but no significant differences in progression-free survival (PFS) or overall survival (OS) were observed (Figs. 8 and 9).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that the splenic index score, calculated by multiplying the splenic volume and NLR before initiating nivolumab treatment in patients with mNSCLC who had progressed after chemotherapy, may be a predictive marker for survival. A high splenic index score, calculated before nivolumab treatment, was found to be statistically significantly associated with shorter OS and PFS, independent of PD-L1 status.

Previous preclinical and clinical studies have indicated that increased splenic volume may serve as an indirect marker of elevated serum MDSC levels and could be linked to immunotherapy resistance6,12,13. In mouse cancer models, spleen enlargement is observed due to extramedullary hematopoiesis and the accumulation of a heterogeneous population of immature myeloid cells, which are recognized as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC). In cancer patients, the spleen serves as a significant reservoir for MDSCs, accumulating these cells and thereby adopting an immunosuppressive role. While lymphoid tissues typically resist MDSC infiltration, the unique structure of the spleen facilitates close interaction between polymorphonuclear MDSC (PMN-MDSC) and T cells, leading to immune suppression14,15,16. ce Tavukçuoğlu and colleagues demonstrated this phenomenon in their human study. Spleen samples from cancer patients have shown a marked accumulation of MDSC, with concurrent suppression of T cell function, suggesting that the spleen contributes to systemic inflammation and may play a role in immune therapy resistance17. However, despite its promising role in understanding the immune response, it is not yet widely applicable in clinical practice.

Likewise, numerous clinical studies have demonstrated the association between peripheral inflammatory markers, such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and immunotherapy resistance18. Despite these findings, no definitive consensus has emerged regarding the use of NLR as a standalone predictive biomarker. In light of these complexities, our study sought to bridge this gap by integrating these two biomarkers—splenic volume as a proxy for MDSC accumulation and NLR as a marker of systemic inflammation—into a novel composite score. This approach is the first of its kind, demonstrating that this combined score is significantly associated with survival outcomes in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), thereby offering a promising tool to predict patient prognosis in the context of immunotherapy.

We would like to highlight that a key mechanism of immune resistance to ICI-based therapy in patients with tumor-associated chronic inflammation is the elevation of MDSC cells, which can be conveniently identified by an increase in splenic volume. Furthermore, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a well-established peripheral marker of chronic inflammation, with a substantial body of literature supporting its relevance19,20,21. In this study, we selected NLR as the primary systemic inflammation marker due to its well-established prognostic significance in malignancies, particularly in the context of immunotherapy. While both NLR and PLR showed significant associations, NLR demonstrated a stronger predictive value, likely due to its more direct reflection of the balance between systemic inflammation and anti-tumor immunity14. Although the splenic index score calculated using PLR yielded statistically similar results, we preferred NLR due to its stronger prognostic relevance and broader clinical applicability.

In chronic inflammation, cytokines such as Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) promote the expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which support tumor progression and contribute to resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) by suppressing the function of T cells and natural killer cells. MDSCs also activate regulatory T cells (Tregs), which increase the production of immunosuppressive cytokines like interleukin-10 (IL-10), thereby inhibiting CD4 + and CD8 + T cell functions and promoting tumor growth22. Consistent with these findings, our study observed that patients with increased splenic volume and high NLR, reflecting a high splenic index score, had the poorest survival outcomes.

Several studies in the literature have explored the relationship between baseline splenic volume, NLR, and response to immunotherapy. Loïck Galland and colleagues found that baseline splenic volume, measured before starting immunotherapy in patients with metastatic NSCLC treated with ICIs, was associated with overall survival (OS). They primarily related this finding to chronic inflammation9. Joao V Alessi and colleagues identified a significant relationship between low baseline NLR and OS as well as PFS in NSCLC patients receiving first-line pembrolizumab23. C Valero and colleagues demonstrated a strong association between baseline NLR and survival in patients undergoing immunotherapy18. M Hwang and colleagues showed a strong relationship between NLR and immunotherapy response24. S Anpalakhan and colleagues found that in a group of patients receiving immunotherapy, including those with NSCLC, lower baseline NLR levels were associated with better clinical responses25.

In contrast to these studies, our research found that baseline splenic volume and NLR levels measured before initiating nivolumab treatment were not statistically significant predictors of survival when considered individually. However, the splenic index score, created by combining these laboratory and radiological parameters, was found to be associated with survival independently of PD-L1 status when evaluated before starting nivolumab.

A study supporting our findings was conducted by Ziyang Zeng and colleagues, who demonstrated a high correlation between increased splenic volume and NLR in gastric cancer patients3. In our study, we observed that the group with an increase in baseline splenic volume accompanied by high NLR—indicating a high splenic index score—had poor OS and PFS.

Some studies investigating the relationship between splenic volume and survival have also, like ours, found no statistically significant association between pre-treatment splenic volume and survival. For example, Francesca Castagnoli et al. found no predictive or prognostic value of changes in splenic volume in patients with advanced NSCLC treated with pembrolizumab26.

Susok et al. examined the impact of immunotherapy on splenic volume in patients with advanced melanoma and found a significant increase in median splenic volume three months after treatment with ICIs compared to baseline, though no correlation with clinical outcomes was noted27. Similarly, Lukas Müller et al. reported an increase in splenic volume following the initiation of immunotherapy in a significant number of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients undergoing first-line treatment. However, this increase was not linked to survival outcomes and was attributed primarily to portal hypertension rather than immune modulation28. In contrast to these studies, we created a score by combining NLR, a strong peripheral indicator of tumor-associated chronic inflammation, with splenic volume. We found that a high splenic index score, derived from this combined assessment, was associated with poor PFS and OS.

The splenic index score appears to be primarily a prognostic biomarker, as it is significantly associated with OS and PFS independent of PD-L1 status, reflecting systemic inflammation and MDSC-driven immunosuppression. However, its potential predictive value cannot be overlooked, as it may help identify patients less likely to benefit from nivolumab, suggesting a role in treatment stratification. To establish its predictive utility, future studies should compare treated and untreated cohorts to determine whether the score specifically influences response to immunotherapy rather than merely reflecting overall disease burden and inflammation.

Several limitations to our study need to be discussed. First, it was retrospective in nature. The sample size was small, and all patients received nivolumab second-line and subsequent therapy at the earliest, due to reimbursement rules in Turkey. Due to the retrospective design of our study, serum samples from that period were not available, preventing simultaneous measurement of MDSCs alongside splenic index assessments. Additionally, our patient population was heterogeneous, including tumors with varying PD-L1 expression levels, and all patients had previously undergone at least one line of systemic chemotherapy, which could have influenced splenic volume and peripheral immune cell profiles. While existing studies have evaluated NLR and splenic volume individually in relation to immunotherapy response, research on their combined use is lacking. Our hypothesis was that multiplying these two biomarkers would yield a more effective prognostic indicator. This study is pioneering in that it is among the first to combine radiological and peripheral inflammatory biomarkers for assessing second-line and subsequent treatments in metastatic NSCLC, thus making a significant contribution to the field.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study suggests that the splenic index score, created by combining radiological and peripheral inflammatory biomarkers, can be used to predict PFS and OS in metastatic NSCLC when PD-L1 levels are not sufficiently predictive in second-line and subsequent treatment phases. Splenic volume appears to be associated with chronic inflammation and MDSC accumulation, known to be related to immunotherapy resistance. To validate these findings, prospective immunotherapy clinical trials that concurrently assess the relationship between changes in splenic index and MDSCs are required.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

21 July 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: An internal SPSS data file was mistakenly included as Supplementary Information and made publicly available. This file contained sensitive or unpublished raw data that was not intended for public sharing. Therefore, the Supplementary Information file and the Acknowledgements section referencing it have been removed.

References

Reck, M., Remon, J. & Hellmann, M. D. First-line immunotherapy for non–small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 40(6), 586–597 (2022).

Garon, E. B. et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 372(21), 2018–2028 (2015).

Schmidt, H. et al. Pretreatment levels of peripheral neutrophils and leukocytes as independent predictors of overall survival in patients with American joint committee on Cancer stage IV melanoma: Results of the EORTC 18951 biochemotherapy trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 25(12), 1562–1569 (2007).

Kim, E. S., Kim, S. Y. & Moon, A. C-reactive protein signaling pathways in tumor progression. Biomolecules Ther. 31(5), 473 (2023).

Stares, M. et al. Prognostic biomarkers of systemic inflammation in Non-Small cell lung cancer: A narrative review of challenges and opportunities. Cancers 16(8), 1508 (2024).

Gabrilovich, D. I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 5(1), 3–8 (2017).

Bronte, V. & Pittet, M. J. The spleen in local and systemic regulation of immunity. Immunity 39(5), 806–818 (2013).

Limagne, E. et al. Accumulation of MDSC and Th17 cells in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer predicts the efficacy of a FOLFOX–bevacizumab drug treatment regimen. Cancer Res. 76(18), 5241–5252 (2016).

Galland, L. et al. Splenic volume as a surrogate marker of immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy in metastatic Non small cell lung cancer. Cancers 13(12), 3020 (2021).

Organization, W. H. & Online News-room fact-sheets detail obesity and overweight. URL: (2020). https://www.who.int/newsroom/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

Prassopoulos, P. et al. Determination of normal Splenic volume on computed tomography in relation to age, gender and body habitus. Eur. Radiol. 7, 246–248 (1997).

Niogret, J. et al. Baseline Splenic volume as a prognostic biomarker of FOLFIRI efficacy and a surrogate marker of MDSC accumulation in metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Cancers 12(6), 1429 (2020).

Liu, C. et al. Blocking IL-17A enhances tumor response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in microsatellite stable colorectal cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 9(1). (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in gastric cancer. Medicine 97(12), e0144 (2018).

Jordan, K. R. et al. Immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells are increased in splenocytes from cancer patients. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 66, 503–513 (2017).

Ku, A. W. et al. Tumor-induced MDSC act via remote control to inhibit L-selectin-dependent adaptive immunity in lymph nodes. Elife 5, e17375 (2016).

Tavukcuoglu, E. et al. Human Splenic polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells (PMN‐MDSC) are strategically located immune regulatory cells in cancer. Eur. J. Immunol. 50(12), 2067–2074 (2020).

Valero, C. et al. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and mutational burden as biomarkers of tumor response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 729 (2021).

Balkwill, F. R. & Mantovani, A. Cancer-related Inflammation: Common Themes and Therapeutic Opportunities. In Seminars In cancer Biology (Elsevier, 2012).

Boissier, R. et al. The prognostic value of the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in renal oncology: A review. in Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. Elsevier. (2017).

Bilen, M. A. et al. The prognostic and predictive impact of inflammatory biomarkers in patients who have advanced-stage cancer treated with immunotherapy. Cancer 125(1), 127–134 (2019).

Law, A. M., Valdes-Mora, F. & Gallego-Ortega, D. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as a therapeutic target for cancer. Cells 9(3), 561 (2020).

Alessi, J. V. et al. Low peripheral blood derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (dNLR) is associated with increased tumor T-cell infiltration and favorable outcomes to first-line pembrolizumab in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer, 9(11). (2021).

Hwang, M. et al. Peripheral blood immune cell dynamics reflect antitumor immune responses and predict clinical response to immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 10(6). (2022).

Anpalakhan, S. et al. Using peripheral immune-inflammatory blood markers in tumors treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: an INVIDIa-2 study sub-analysis. Iscience 26(11). (2023).

Castagnoli, F. et al. Splenic volume as a predictor of treatment response in patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving immunotherapy. Plos One. 17(7), e0270950 (2022).

Susok, L. et al. Volume increase of spleen in melanoma patients undergoing immune checkpoint Blockade. Immunotherapy 13(11), 885–891 (2021).

Müller, L. et al. Baseline Splenic volume outweighs Immuno-Modulated size changes with regard to survival outcome in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma under immunotherapy. Cancers 14(15), 3574 (2022).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Approval for the study was obtained from the Gazi University Ethics Committee on December 13, 2023, with the application number 27b4ab49-d82f-413f-8878-ad4fd24f4115.Ethics committee approval has been obtained stating that informed consent will not be required due to the retrospective nature of the stud.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aslan, V., Karabörk Kılıç, A.C., Rustamova Cennet, N. et al. Splenic index score as a predictor of outcomes in metastatic non small cell lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Sci Rep 15, 15781 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00708-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00708-w