Abstract

This study focuses on developing a machine learning-based crop yield prediction model suitable for agricultural conditions in Eastern Ethiopia, presents research that has taken cognizance of the fact that agriculture occupies the leading role in the economy through providing a source of livelihood for most Ethiopians and being one of the main contributors to the nation’s GDP. Thus, addressing challenges such as low productivity and food insecurity induced by climate change and environmental factors becomes paramount. Agriculture in Ethiopia is very sensitive to changes in weather conditions, soil degradation, and other ecological factors; hence, exact yield forecasting is quite indispensable for proper planning and resource management of the sector. It integrates various data sets that include local Agri-data, historical yield records, and satellite-derived environmental information. Advanced machine learning algorithms have been considered in the model, such as Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, KNN, and Decision Tree regressors for the prediction of yields precisely. The methodology involved rigorous data preprocessing, feature selection, and model training to give robustness and reliability to predictions. Results clearly indicated that the Random Forest Regressor model outperformed all other alternative models and showed its prospect of enhancing agricultural productivity by informing decisions to be taken by the farmers and other stakeholders. This research underlines technology utilization as a means of optimizing crop management practices, one of the crucial pre-conditions for improved food security and sustainable agricultural development in the region. The results of this study do not end at the immediate farming outcomes but also remind that technology-driven interventions may potentially address broader socio-economic problems in Eastern Ethiopia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ethiopia’s economy is primarily agrarian, with agriculture playing a pivotal role in national development and food security. Approximately 85% of the population depends on agriculture for their livelihood, and the sector contributes 43% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 80% of export revenues (World Bank, 2020). The eastern regions of Ethiopia, known for producing crops like potatoes, khat, and onions, are integral to the nation’s food supply and economy. Despite its importance, the agricultural sector faces challenges related to productivity, environmental factors, and climate change, which threaten food security and economic stability. Agriculture in Ethiopia is influenced by various factors, such as soil fertility, climate conditions, and crop-specific data1,2. These challenges have led to the rise of technology-driven solutions, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), which offer the potential to optimize crop production and empower farmers with better decision-making tools.

Machine learning, a subset of AI, is transforming industries by enabling systems to learn from data and improve over time, without the need for explicit programming3. By utilizing advanced ML algorithms, this research aims to predict the most suitable crops for cultivation in Ethiopia, factoring in parameters such as weather conditions, soil types, and historical yield data. This approach promises to increase agricultural productivity, improve food security, and support rural livelihoods.

This study proposes the development of a machine learning-based crop yield prediction model tailored to the specific agricultural conditions of Eastern Ethiopia. By combining satellite imagery and remote sensing technologies, this research aims to enhance the accuracy of crop yield predictions, reduce food insecurity, and foster sustainable agricultural practices. The model focuses on the most influential factors for crop production, including rainfall, temperature, and soil properties, and provide farmers with actionable data to improve productivity. This work aims to not only address immediate challenges faced by farmers but also contribute to the long-term resilience of the agricultural sector in Ethiopia, especially in the face of climate change and economic uncertainty. Through advanced data analytics and machine learning, this research envisions transforming agricultural practices and improving the livelihoods of smallholder farmers across the country.

Agriculture is the mainstay of the Ethiopian economy and has played an important and significant role in national development and food security. An estimated 85% of the population relies on this sector for its livelihood. The sector contributes about 43% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 80% of export revenues of the country (World Bank, 2020). Production in the eastern regions of Ethiopia shows much importance for the nation’s food supply and economy, especially when different crops are produced there, such as potatoes, khat, and onions. However, despite the vital nature of this industry, productivity, environmental factors, and lately climate change pose serious challenges to agricultural production that undermine food security and economic stability. Various factors have been enumerated to represent yield in Ethiopian agriculture by soil fertility, climate condition, and crop-specific information. These are some of the challenges that have further fanned the growth of technology-enabled solutions such as AI and ML, which hold promises for improving crop production and enabling farmers to make better decisions with unforeseen opportunities. With the power to enable systems to learn from data and improve with time, Machine Learning, a subset of AI, has begun transforming industries without necessarily programming them explicitly. This research uses advanced ML algorithms to predict suitable crops for cultivation in Ethiopia, taking weather conditions, soil types, and historical yield data as parameters. This hopefully could enhance agriculture productivity, food security, and rural livelihoods.

Most of the traditional approaches used for estimating crop yield in Ethiopia involve field visits and manual data collection, which usually is expensive, inconsistent, and full of human errors. The current approaches also cannot provide timely information critical for making appropriate decisions on food trade and transport, especially during food shortages or surpluses. Besides, only a handful of sophisticated equipment for crop yield forecasting has exposed most smallholder farmers in most eastern regions to food insecurity. Satellite-based remote sensing has thus become one of the promising tools, supported by rigorous acquisition of timely and accurate spatial data for crop yield forecasting enhancements. The integration of remote sensing data within the field of agriculture locally can offer a significant deal of valuable information about environmental conditions and crop health in support of farmer decision-making.

This study has developed a machine learning-based crop yield prediction model suitable for prevailing agricultural conditions in Eastern Ethiopia. The fusion of satellite imagery and remote sensing technologies will help improve crop yield predictions, which will reduce increasing incidents of food insecurity and promote sustainable agricultural practices. The model focus on the most influential factors affecting crop production—rainfall, temperature, and soil property measures—to build actionable insights that farmers can use to improve productivity. This will be of importance not only in solving some of the imminent challenges faced by farmers but also to the resilience of the agricultural sector in Ethiopia, in the varying climate and economic uncertainty. This research aims to revolutionize agriculture and livelihoods for small-scale farmers throughout the nation by utilizing advanced analytics and machine learning.

Related works

Machine learning has received increasing attention in the past few years in various industries including agriculture, such as crop yield prediction. Many researchers have proposed high-technology strategies to improve agricultural production and address farmers’ constraints. This review summarizes progress in the field and identifies key research gaps. Machine learning algorithms have been shown to perform well for yield prediction in many studies. The work of1, who used machine learning to predict environmentally affected crop yields in Ethiopia, illustrates the importance of extensive datasets such as weather data and geographic information will be used to make better forecasts Attention has been accepted.

Basir et al.4 demonstrated how well ANN predicts crop yield by analyzing climate data, soil properties, and other inputs. The study looked at the ability of ANNs to model complex interactions, resulting in accurate outcome predictions. Random forest and decision tree algorithms have also shown promise in agricultural settings. Prasath et al.5 conducted a random forest study to predict crop yields and highlighted its robustness through large data sets and ability to reveal key features.

Despite these advancements, challenges persist. Many models depend heavily on historical data, which can hinder accuracy under climate variability. Furthermore, most research overlooks unique agricultural practices and socio-economic factors specific to regions like Ethiopia. Tailored solutions that address these specific needs remain underdeveloped, especially in the context of small-holder farmers and resource-constrained settings. Addressing these gaps will be vital for further advancements in agricultural machine learning applications.

Research gap

While deep learning techniques such as ANNs and CNNs have shown strong performance in modeling nonlinear agricultural trends, some studies argue that they require large, high-quality datasets and often lack interpretability, making them less suitable for smallholder farming contexts. Conversely, tree-based methods like Random Forest and Gradient Boosting offer greater robustness with limited data, making them more practical for regions with scarce datasets6.

Although significant progress has been made in applying machine learning techniques for crop yield prediction, there are still many important research gaps that need to be further investigated. Most of the existing studies prefer general models that generally do not consider specific agricultural conditions in eastern Ethiopia. Importantly, this region lacks locally developed crop forecasting models that incorporate unique environmental, cultural and socioeconomic factors that determine crop production. Besides, many studies rely on limited datasets, which combine different data such as remote sensing, soil health measures and socioeconomic indicators. These data are aggregated while ignoring potential profits can greatly improve the accuracy and reliability of yield forecasts.

In addition, the challenges and unique needs of smallholder farmers, who represent a large portion of the Ethiopian agricultural workforce, are often overlooked. There is an urgent need to develop more accessible and user-friendly models that cater to technologically literate farmers meeting the needs of diversity. Many existing machine learning models also suffer from overfitting, excelling in training data sets but struggling to consistently work with new and unseen data. This limitation is a particular problem in agriculture, where environmental conditions vary widely.

Further research should focus on developing models that maintain robust predictive accuracy across diverse datasets and changing conditions. Additionally, most studies fail to consider the long-term sustainability of agricultural practices and the resilience of crops to climate change. Incorporating climate variability and its effects on crop yields is essential to devise adaptive strategies for farmers. By addressing these gaps, advancements in crop yield prediction models can contribute to broader objectives, such as sustainable agricultural development and enhanced food security in Eastern Ethiopia. This research aims to bridge these gaps by focusing on locally relevant solutions and leveraging integrated datasets to deliver actionable insights for farmers and stakeholders in the region.

Materials and methods

This section explains how we created a machine learning model for predicting crop yields in Eastern Ethiopia. We followed several steps: collecting data, preparing it, building the model, and testing it. Our goal was to use advanced machine learning to help farmers by making accurate yield predictions. We used different datasets and strong analytical methods. This research aims to give farmers useful insights. It helps them make better decisions to improve food security and their economic situation.

Data collection

We got our data from the Ethiopian Statistical Services (ESS) and NASA. A detailed farming information and the environment in Eastern Ethiopia for the year ranging from 2004 to 2017. By combining local farming data with global environmental information, we could deeply analyze what affects crop productivity.

Data source

The dataset used in this study integrates agricultural, climatic, soil, and topographical variables, ensuring a multidimensional approach to crop yield prediction. Agricultural parameters include season, region, zone, district, crop, area (sq.m), yield, and crop_category. Soil attributes include elevation, slope, soc (soil organic carbon), and soilph. Climatic and environmental factors are also GWETPROF, GWETTOP, GWETROOT (groundwater moisture levels), CLOUD_AMT (cloud cover), TS (surface temperature), PS (surface pressure), RH2M (relative humidity), QV2M (specific humidity), PRECTOTCORR (corrected precipitation), T2M_MAX, T2M_MIN, T2M_RANGE (temperature variations), and WS2M (wind speed).

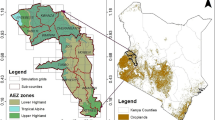

To ensure the representativeness of the dataset, we validated it through multiple methods. The dataset spans from 2004 to 2017, covering 33 districts across Eastern Ethiopia, and includes data from the Fall (Belg) and Winter (Meher) seasons, which capture varying climatic conditions and crop cycles. To make that the model is continuously updated with the latest environmental conditions we have integrated NASA’s satellite-based environmental monitoring, which automatically updates real-time climate parameters into the prediction model.

Data description

The data spanned from 2004 to 2017 and had many important features for predicting crop yields. The dataset included:

Year: The year of data collection, providing a temporal context for the analysis and allowing for the identification of trends over time. This feature is critical for understanding how yield patterns may have changed in response to various factors, including climate change and agricultural practices7.

Season: The agricultural season (e.g., summer, winter) during which the data was recorded. This allows for seasonal variations in crop yield to be analyzed and provides insight into how different crops perform in different seasons. Understanding seasonal impacts is vital for optimizing planting and harvesting schedules8,9.

Region: The broader geographical area in which the data was collected. This facilitates regional comparisons and provides insights into the impact of geographical diversity on agricultural outcomes. Different regions may exhibit varying climatic conditions and agricultural practices, influencing yield10.

Zone: A more specific sub-region within the broader region, which enables a more localized analysis of agricultural practices and outcomes. This granularity allows for targeted interventions and recommendations based on local conditions.

Wereda: The smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia, which represents local governance and allows for an understanding of how local policies, infrastructure, and governance affect agricultural productivity. This feature is essential for assessing the impact of local governance on agricultural success.

Crop: The type of crop being cultivated (e.g., maize, potatoes). This allows for crop-specific yield predictions and helps identify which crops are most affected by the factors in the dataset. Understanding crop diversity is important for tailoring agricultural practices to specific crops.

Area (sq.m): The area of land (in square meters) allocated for the crop. This is an essential factor influencing yield and provides insight into how land allocation affects productivity. Larger areas may yield more, but efficiency and management practices also play a critical role11.

Yield: The total yield of the crop (in tons), which serves as the target variable for the machine learning model. This is the primary outcome of interest and is critical for evaluating the effectiveness of agricultural practices.

Crop_Category: Classification of the crop (e.g., food crops, cash crops), helping in understanding the economic significance and focus of agricultural practices. This categorization aids in analyzing the economic implications of different crops.

ALLSKY_SRF_ALB: Surface albedo data, indicating the reflectivity of the earth’s surface, which influences local climate conditions. Albedo affects temperature and moisture levels, impacting crop growth.

AOD_55: Aerosol optical depth, a measure of the aerosols in the atmosphere, which can affect weather patterns and consequently crop growth. Understanding aerosol levels is important for assessing air quality and its impact on agriculture12.

CLOUD_AMT: The amount of cloud cover, which is relevant for understanding the availability of sunlight to crops. Sunlight is essential for photosynthesis, and cloud cover can significantly influence crop yields.

FROST_DAYS: The number of frost days recorded in the region. Frost can severely affect crop yield, particularly frost-sensitive crops. This feature is critical for assessing the risk of frost damage.

GWETPROF: Groundwater profile data, providing insights into water availability for irrigation, which is critical in drought-prone areas. Groundwater availability is a key factor in determining irrigation practices.

GWETROOT: Groundwater data at root depth, critical for assessing moisture availability to crops during dry periods. This information is vital for understanding irrigation needs.

GWETTOP: Groundwater data at the topsoil level, which influences surface moisture conditions. Topsoil moisture is essential for seed germination and early crop growth13.

PRECIPITATIONCAL: Calculated precipitation data, essential for understanding rainfall patterns and water availability. Precipitation is a primary driver of crop growth and yield.

PRECTOTCORR: Total corrected precipitation data, providing a more accurate picture of actual water availability from precipitation. Accurate precipitation data is key for effective water management.

PS: Surface pressure data, which can influence local weather patterns and crop growth. Understanding pressure systems is important for predicting weather events.

QV2M: Specific humidity at 2 m above ground level, relevant for understanding moisture levels in the air, which affects plant transpiration rates. Humidity plays a critical role in plant health and growth.

RH2M: Relative humidity at 2 m above ground level, which directly affects plant transpiration rates and crop health. High humidity can lead to disease pressure, while low humidity can stress plants.

T10M: Temperature at 10 m above ground level, providing insights into atmospheric conditions. Temperature influences crop growth rates and development.

T2M: Temperature at 2 m above ground level, which is critical for understanding growing conditions. This feature is essential for assessing heat stress on crops.

T2M_MAX: Maximum temperature at 2 m, which can indicate stress levels for crops exposed to extreme heat. High maximum temperatures can lead to reduced yields.

T2M_MIN: Minimum temperature at 2 m, essential for assessing frost risk, which may impact sensitive crops. Low minimum temperatures can damage crops.

TS: Surface temperature data, influencing soil moisture and crop growth. Surface temperature affects evaporation rates and soil moisture levels.

WS10M: Wind speed at 10 m above ground level, which influences evapotranspiration rates and can affect crop yield in windy conditions. Wind can exacerbate water loss from plants.

WS2M: Wind speed at 2 m above ground level, relevant for understanding microclimates and localized impacts on crops. Wind patterns can affect local weather conditions and crop health.

This dataset provides a detailed look at factors affecting crop yield in Eastern Ethiopia. It allows for a deep analysis of how agricultural practices and environmental conditions interact. By using these diverse features, the predictive model can handle the complex nature of agricultural productivity.

Data preprocessing

Data preprocessing is key in getting the dataset ready for machine learning model development. The raw data needs to be cleaned, standardized, and transformed into a format suitable for model training. Several steps were taken to ensure the data is clean, consistent, and ready for analysis.

Data cleaning

The first step in data preprocessing was cleaning the dataset. This involved handling missing values, duplicates, and inconsistencies. Missing values were filled using different methods based on the data type. For continuous data, mean or median imputation was used. Duplicates were removed to prevent biases. Inconsistent data was corrected using domain knowledge. This cleaning process is key to ensuring the dataset’s integrity. It makes the data reliable for further analysis.

Normalization

Next to ensure uniformity numerical features were normalized to make all features comparable, preventing any from dominating the model. Normalization is a crucial preprocessing step in data analysis and machine learning. It involves adjusting the scales of input features to ensure uniformity, which enhances the performance and stability of algorithms. This process is particularly important when features have different units or varying ranges, as it prevents features with larger scales from disproportionately influencing the model. This step enhances the model’s learning ability and performance. In data processing, normalization refers to the process of adjusting values measured on different scales to a common scale, often prior to averaging14.

Encoding categorical variables

Categorical variables like ‘Season’, ‘Region’, ‘Zone’, and ‘Crop’ were converted to numbers. One-hot encoding was used for unordered features, and label encoding for ordered ones. This transformation is necessary for algorithms that require numerical inputs. Proper encoding ensures the model can interpret and use these features effectively.

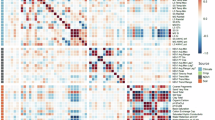

Feature selection

Feature selection identified the most relevant features for predicting crop yield. Correlation analysis and statistical tests were used to evaluate feature relationships with yield. Features strongly correlated with yield were kept. This step improves model efficiency and reduces overfitting by removing unnecessary features. Focusing on impactful features enhances model performance and interpretability.

Data splitting

The dataset was split into training and testing sets. 80% were for training, and 20% for testing. This division helps evaluate model performance on unseen data, preventing overfitting. The training set was used to fit the model, and the testing set to assess its performance. This approach is essential for real-world effectiveness.

Model development

After preprocessing, machine learning models were developed for crop yield prediction. Four algorithms were used: Gradient Boosting Regressor, Random Forest Regressor, K Neighbors Regressor, and Decision Tree Regressor. The selection of these algorithms was based on their ability to handle diverse data characteristics and optimize predictive accuracy.

These selected models able to balance accuracy, interpretability, and computational efficiency, ensuring a comprehensive evaluation of predictive performance across varying agricultural conditions15,16,17.

-

Gradient Boosting Regressor: Gradient Boosting combines weak models to create a strong predictive model. Each tree corrects the previous one’s errors, improving the model with each iteration. It’s suitable for diverse data, making it a good choice for this study18. This method’s iterative nature leads to more accurate predictions as the model refines itself continuously.

-

Random Forest Regressor: Random Forest is a method that uses many decision trees to make predictions. It’s different from Gradient Boosting because it builds trees separately and averages their results. This helps avoid overfitting and works well with big datasets and lots of features19.

-

K Neighbors Regressor: K Neighbors Regressor uses the average output of the k-nearest neighbors to predict. The number of neighbors (k) is key and was chosen during development. It’s good at finding local patterns and is easy to use when you don’t know much about the data.

-

Decision Tree Regressor: A Decision Tree Regressor splits data into subsets based on feature values. It makes predictions at the leaf nodes. Each split aims to reduce the variance in the target variable (crop yield). Decision trees are easy to understand and can handle non-linear relationships.

Model evaluation

To judge how well the models work, several metrics were used. These metrics help see how well the model predicts crop yield, covering both accuracy and how well it generalizes.

-

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): The RMSE shows the average difference between predicted and actual crop yields. It’s a key metric for regression tasks. A lower RMSE means the model is doing better. RMSE is useful because it shows the size of the prediction errors in the same units as the target variable20.

-

R2 Score: The R2 score shows how much of the variance in the target variable (yield) the model explains. A higher R2 score means the model is more accurate. This metric is key for seeing how well the model captures the data’s underlying relationships.

-

Cross-Validation: Cross-validation is a statistical method used to evaluate and compare learning algorithms by dividing data into two segments: one used to learn or train a model and the other to validate the model. This technique helps in assessing how the results of a statistical analysis will generalize to an independent dataset21. Cross-validation was used to ensure that the models generalized well and were not overfitting. The data were divided into several subgroups, and the model was trained and validated in a circular manner in subgroups. This approach helps to assess the stability and reliability of model performance on different subsets of data, thus reducing the potential for bias in performance analysis. Cross validation is an important step in model evaluation in, as an example compared to rail test separations -for very strong estimates of performance.

Proposed architecture

The study is structured around a series of systematic steps designed to achieve its objectives effectively. Each of these steps plays a crucial role in the overall process, ensuring that the data is handled appropriately and that the resulting models are robust and reliable. The key activities involved in this study include data collection, data preprocessing, model building, model validation, and model tuning. Each of these stages is elaborated upon below:

-

Raw Data: This initial phase is special because it involves defining the target data and focusing on the selection of data models for predictive analysis This study collected data from the Agricultural Research Station in eastern Ethiopia, somewhere with rich agricultural details to be found. The list includes the criteria necessary to identify crops suitable for agriculture. It includes climate data, soil properties, and historical crop yield data. This summary forms the basis for subsequent research, enabling informed crop selection decisions based on empirical evidence.

-

Data Preprocessing: Once raw data is collected, the next important step is data preprocessing. In this phase, the dataset is thoroughly tested to ensure its quality and reliability. Such basics as completeness, excess, missing values, and the usefulness of feature values are carefully verified. Data preprocessing involves cleaning and transforming the target data into an accurate and uniform dataset. This may involve transforming data from sources into another standardized format, which is necessary to ensure that the data is suitable for analysis. By addressing these issues at this stage, the aim of the analysis is to improve the accuracy and efficiency of subsequent sampling efforts.

-

Building Model: Once the data has been preprocessed, the next step is to build predictive or descriptive models using machine learning techniques. This stage is pivotal as it involves applying various algorithms to the cleaned dataset to derive insights and predictions regarding crop yield. The choice of machine learning techniques will depend on the nature of the data and the specific objectives of the study. By leveraging these advanced analytical methods, the study aims to uncover patterns and relationships within the data that can inform agricultural practices and decision-making.

-

Model Validation: Validation is required to determine the expected accuracy, specificity, applicability, and reasonableness of the fitted model. It is an important step in the modeling process. This step involves evaluating the performance of the model with statistical and reasonable criteria. Understanding the implications of the model, determining that the results are original and of interest, and interpreting the results with the help of subject matter experts are all important. This collaborative approach is reassuring, for example, identification is important and useful in real-field situations. All interventions will be analyzed for additional efforts that can improve outcomes, and only those models that meet predefined acceptance criteria will be retained for subsequent analyses.

-

Model Tuning: The final step in the conceptualization process, model tuning, is to adjust the parameters and hyperparameters of the model in response to the analytical results of the validation step. This iterative process is necessary to increase model performance and ensure that the predictions are as accurate as possible. The study intends to improve the predictive power of the model by adjusting, resulting in more reliable recommendations for resource allocation and crop management. The diagram that follows provides a visual representation of the conceptual framework of the study, showing how these stages interact and how the research process flows in. This framework serves as a strategic framework for the study conduct the study, ensuring that each stage is well thought out and managed to produce the desired results. The architecture of the proposed system is shown in the Fig. 1 below.

Results and discussion

This section presents the results of the evaluation of four machine learning models used to predict crop yields based on various environmental, agricultural, and meteorological features. The models include the Gradient Boosting Regressor, Random Forest Regressor, K Neighbors Regressor, and Decision Tree Regressor. These models were evaluated based on several key performance metrics, including Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), R2 scores for both the training and test datasets, and cross-validation scores. The analysis explores how each model performed and compares these results to similar studies in agricultural yield prediction, providing insights into their effectiveness and applicability in real-world scenarios.

The evaluation results are summarized below in Table 1, showing the RMSE, R2 score (training), R2 score (test), and cross-validation scores for each model:

The diagrams on Fig. 2 shows R2 Score for training and testing whereas the graph on Fig. 3 shows RMSE score of the models.

Random forest regressor

The random forest regressor (RFR) performed better than the other models with a lower RMSE (170.17), indicating better prediction accuracy. It also achieved an R2 score of 0.99 on the training dataset, indicating that it can explain almost all the variance in crop yield data. The test dataset R2 score of 0.96 further supports this, demonstrating the model’s ability to generalize well to unobserved data. The cross-validation score of 0.95 indicates that the model performs consistently well on different data subsets, further confirming its robustness. The strong performance of RFR is consistent with observations in studies in similar settings. In this study, the random forest regressor is the most appropriate model due to its high prediction accuracy, good generalization, and stability across data bundles and is the best tool for crop yield prediction, especially during consumption complex, high-quality data processing sets with many interacting variables. The ability to handle nonlinear relationships and interactions among random forest variables is especially valuable in agricultural settings, where such challenges are common. The strength of this model is its adaptability to data diversity further enhances its application in real-world agricultural situations.

Gradient boosting regressor

The gradient boosting regressor (GBR) had an RMSE of 184.72, indicating a higher prediction error compared to the random forest regressor but still acceptable for many agricultural experiments. R2 scores with the training dataset (0.96) indicate that the GBR model can significantly explain part of the crop yield variation depending on input characteristics. A test data set R2 score of 0.96 indicates that the model is effective.

Compared to similar studies, GBR performance is consistent with those typically obtained in agricultural forecasting. For example, a study by Mohammad et al. (2020) used the Gradient Boosting model to predict wheat yield in arid regions, obtaining R2 scores (0.84–0.89) and RMSE values. Such findings suggest that although GBR is effective in detecting complex relationships in agricultural data, a balance between training and test performance is needed to avoid overfitting. The findings suggest that although GBR can capture complex patterns, it needs to be carefully developed and validated to ensure its robustness in practical applications.

K neighbors regressor

The K Neighbors Regressor (KNN) showed a reasonable performance with an RMSE of 202.06, higher than both the Random Forest and Gradient Boosting models. The R2 scores were 0.95 for the training dataset and 0.94 for the testing dataset, indicating a significant phase some of the differences in KNN data can be explained but compared to other models. It struggles with generalization. A cross-validation score of 0.93 indicates consistent performance across different subsets of data but still following other patterns. Although KNN is often considered as a simple but effective method for constructing regression functions, it is highly sensitive to the choice of k (number of neighbors) and distance metric. Liu et al. (2017) used KNN to predict crop yields in China and reported similar R2 scores (0.80–0.85), noting that although KNN is interpretable, and it is easy to implement though it can handle complex data with large features well such as Random and cluster-. Cannot handle forests or gradients as well as paths Boosting. The findings suggest that although KNN can be a useful tool in some circumstances, its limitations in dealing with complex relationships in agricultural data may hinder its application will be used in more difficult situations. In addition, the performance of the KNN model can be significantly affected by the telemeter selection and scaling of the input features. In agricultural datasets, where features can vary significantly in scale, appropriate generalization is needed for KNN to perform well. Future research could investigate the optimal choice of k and test different distance measures to further enhance model performance.

Decision tree regressor

The decision tree regressor (DTR) exhibited an absolute training R2 score of 0.99, indicating a good fit to the training data. The performance of the model on the test data set is (R2 = 0.95). The RMSE of 211.71, while lower than KNN and gradient boosting, is still higher than Random One, indicating that DTR does not provide the most accurate prediction and while the cross-validation score of 0.94 is still good of, but lower than the ensemble model. While the decision tree model is a valuable tool for understanding feature importance and correlation. The findings highlight the importance of using techniques such as cross-validation and pruning to enhance the model’s ability to generalize.

Despite its limitations, the decision tree model offers semantic advantages, enabling stakeholders to understand the decision-making processes behind forecasts. This transparency can be particularly useful in agricultural contexts, where logic the forecasting of factors affecting yield is very important for effective increasing decision making is a central area.

Comparison with other studies

The results of this study are consistent with the findings of other studies where machine learning methods have been used to predict agricultural production such as9 used random forest and gradient boosting models to predict wheat yield and found that random forest consistently outperforms other models in terms of R2 score and RMSE as well as22 compared Decision Trees, Random Forest, and Gradient Boosting for wheat yield prediction in India, and Random Forest gave the most accurate results, followed closely by Gradient Boosting. Furthermore, the comparative analysis of these models highlights the importance of selecting an appropriate algorithm based on the specific characteristics of the dataset and farming situation. As farming practices evolve and the availability of data increases, machine learning the integration of advanced methods will be essential to improve crop forecasting and support sustainable agricultural practices.

Implications for agricultural decision-making

The findings from this study are broadly applicable to agricultural stakeholders, including farmers, policymakers and researchers. With accurate prediction, the random forest regressor can be used as a reliable tool for crop yield prediction. Accurate crop forecasts enable better allocation of resources, improve agricultural practices, and help develop climate adaptation strategies.

To bridge the gap between AI research and practical applicability, we developed a web and mobile-based platform that integrates real-time NASA API data, providing farmers, policymakers, and stakeholders with location-specific, AI-driven insights for enhanced productivity and climate resilience. The platform features a cloud-integrated, user-friendly design, allowing users to input season, district, and land area to generate yield forecasts. It dynamically retrieves live climatic data, ensuring continuous updates based on current weather patterns. It’s designed for scalability and accessibility; the platform supports low-bandwidth environments to ensure usability in rural and remote areas. By automatically syncing with NASA’s climate data, the platform revolutionizes yield forecasting, strengthens climate adaptation strategies, and optimizes agricultural resource management. The following Figs. 4 and 5 shows a sample interface of the developed mobile application.

In addition, policymakers can use such models to forecast future food production, inform decisions about food security, market operations, and agricultural development plans. The ability to accurately predict crop yield’s ability to make dynamic and data-driven decisions etc. in success challenges Specifically, to integrate these predictive models into agricultural planning, it can lead to more robust agricultural systems and improved food security consequently.

Furthermore, insights from this study could lead to the development of targeted interventions and support programs for farmers, especially smallholder farmers who may be vulnerable to crop yield fluctuations. By leveraging the predictive capabilities of machine learning models, agricultural extension agencies can provide tailored advice and support to farmers, enabling them to adapt to changing conditions and produce if they are done well. Even though the results of the random forest regressor model are promising, there are technological and infrastructure barriers to implementing the proposed models for smallholder farmers.

The lack of technology literacy among smallholder farmers can make it difficult for them to adopt new models. To deal with this, develop tools that are easy to use on mobile devices, intuitive, and visually straightforward. Arrange training programs with community organizations, NGOs, or local agricultural extension services to give farmers practical instruction on how to use the technology. To overcome infrastructure constraints such as restricted availability of dependable hardware, electricity, and internet, create technologies that can function offline or with little connectivity, synchronizing data when the internet is accessible, make sure it works with inexpensive smartphones or feature phones, as these are more affordable for smallholder farmers. To combat the lack of electricity, investigate forming alliances with companies that offer solar-powered devices.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study successfully developed a machine learning-based crop yield prediction model tailored to the specific agricultural conditions of Eastern Ethiopia. By integrating diverse datasets, including local agricultural data and satellite-derived environmental information, the model demonstrated the potential to enhance agricultural productivity and food security in the region. The evaluation of various machine learning algorithms revealed that the Random Forest Regressor outperformed other models, providing accurate and reliable yield predictions. The findings underscore the importance of utilizing advanced data analytics and machine learning techniques to address the challenges faced by smallholder farmers in Ethiopia. By providing actionable insights into crop yield dynamics, the model can empower farmers and stakeholders to make informed decisions, ultimately contributing to improved agricultural practices and enhanced resilience against climate variability.

Future research should focus on refining the model further, incorporating additional data sources, and exploring the integration of real-time monitoring systems to enhance the accuracy and applicability of yield predictions.

The following are some recommendations for future work:

-

Integrate Transformers, GNNs, and hybrid LSTM-Transformer models to improve crop yield forecasting and reduce reliance on labeled data with self-supervised learning.

-

Develop low-cost, energy-efficient IoT sensors for real-time soil health, nutrient, and disease monitoring, combined with satellite and drone data for hyper-localized insights.

-

Use reinforcement learning to create AI systems that adjust irrigation, fertilization, and pest control in real-time based on weather, soil, and crop data.

-

Develop low-bandwidth, offline AI interfaces with voice assistance in local languages and leverage edge computing for smallholder farmers. Collaborate with NGOs for training and adoption.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gashaw Molla Teshome and Inderjeet Singh Sidhu, “Growth Decomposition and Productivity in Ethiopia, 2000–2018,” Semant. Sch. (2020).

Kumar, R. S. Agricultural analysis for next generation. 1(10), 82–86 (2016).

Kandel, M., Rijal, T. R. & Kandel, B. P. Evaluation and identification of stable and high yielding genotypes for varietal development in amaranthus (Amaranthus hypochondriacus L.) under hilly region of Nepal. J. Agric. Food Res. 5, 10015 (2021).

Basir, M. S., Chowdhury, M., Islam, M. N. & Ashik-E-Rabbani, M. Artificial neural network model in predicting yield of mechanically transplanted rice from transplanting parameters in Bangladesh. J. Agric. Food Res. 5, 100186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2021.100186 (2021).

Prasath, N., Sreemathy, J., Krishnaraj, N. & Vigneshwaran, P. Analysis of crop yield prediction using random forest regression model BT—Information systems for intelligent systems. In So-In, C., Londhe, N. D., Bhatt, N. & Kitsing, M. (Eds.) Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, pp. 239–249 (2023).

Sharma, P., Dadheech, P., Aneja, N. & Aneja, S. Predicting agriculture yields based on machine learning using regression and deep learning. IEEE Access 11, 111255–111264. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3321861 (2023).

Rolnick, D. et al. Tackling climate change with machine learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 55(2), 1–96. https://doi.org/10.1145/3485128 (2023).

Dwivedi, Y. K. et al. Climate change and COP26: Are digital technologies and information management part of the problem or the solution? An editorial reflection and call to action. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 63(November), 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102456 (2021).

Devi, M., Kumar, J., Malik, D. P. & Mishra, P. Forecasting of wheat production in Haryana using hybrid time series model. J. Agric. Food Res. 5 (2021).

Khandelwal, I., Adhikari, R. & Verma, G. Time series forecasting using hybrid arima and ann models based on DWT Decomposition. Procedia Comput. Sci. 48(C), 173–179 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2015.04.167.

Kassie, M. Adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices: Evidence from micro-level studies in Africa. Environ. Sci. Policy 36, pp. 37–51 (2014).

Malyadri, N., Srikanth, M. S. & A. B. J. Recommendation model for crop and fertilizer 8(5), 10531–10539 (2021).

Radeny, M. et al. Indigenous knowledge for seasonal weather and climate forecasting across East Africa, pp. 509–526 (2019).

Sankpal, K. A. A review on data normalization techniques. Int. J. Eng. Res. (2020). https://doi.org/10.17577/IJERTV9IS060915.

Geeksforgeeks. Random Forest Regression in Python. Accessed: Feb. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/random-forest-regression-in-python/

Kaliappan, J., Srinivasan, K., Mian Qaisar, S., Sundararajan, K. C.-Y. & Chang, S. C. Performance evaluation of regression models for the prediction of the COVID-19 reproduction rate. Front. Public Health (2021). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.729795.

Mahamat, A. A. et al. Decision tree regression vs. gradient boosting regressor models for the prediction of hygroscopic properties of borassus fruit fiber. Appl. Sci. 14(17), 7540 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/app14177540.

Hashim, S. A., Awadh, W. A. & Hamoud, A. K. Student performance prediction model based on supervised machine learning algorithms. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/928/3/032019.

You, J., Li, X., Low, M., Lobell, D. & Ermon, S. Deep Gaussian process for crop yield prediction based on remote sensing data. 31st AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence AAAI, 2017, pp. 4559–4565 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v31i1.11172

Willmott, C. & Matsuura, K. Advantages of the mean absolute error (MAE) over the root mean square error (RMSE) in assessing average model performance. Clim. Res. 30, 79–82. https://doi.org/10.3354/cr030079 (2005).

Refaeilzadeh, P., Tang, L. & Liu, H. Cross-validation BT—Encyclopedia of database systems,” Liu, L. & Özsu, M. T. (Eds.) Boston, MA: Springer US, 2009, pp. 532–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-39940-9_565.

Jain, P. “AI in Agriculture | Application of Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture.” Accessed: Sep. 27, 2021. [Online]. https://www.analyticsvidhya.com/blog/2020/11/artificial-intelligence-in-agriculture-using-modern-day-ai-to-solve-traditional-farming-problems

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A. conceptualized the study, developed the methodology, and wrote the main manuscript text. A.A. contributed to data collection, preprocessing, and model training. D.A. conducted the performance evaluation of the machine learning models and prepared Figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abate, J., Aman, A. & Adem, D. Integration of satellite data for predicting crop yields in Eastern Ethiopia using machine learning. Sci Rep 15, 33809 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00810-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00810-z