Abstract

Recent scientific studies exploring the neuropsychological foundations of moral decision-making have shown that moral attitudes and evaluations are significantly influenced by emotion, particularly negative emotionality, as well as personality traits such as neuroticism. Further psychopharmacological research has observed that GABAergic agonists are capable of influencing moral decision-making by modifying anxiety-related emotional negativity and/or through cognitive modulation. The aim of this double-blind, crossover design, placebo-controlled study is to evaluate said GABAergic modulation on moral cognition. Importantly, unlike the aforementioned research, the present study not only utilizes explicit moral evaluation measures [e.g., the Justice Sensitivity Inventory (JSI) and evaluations of moral scenarios], but also uses the morality Implicit Association Test (mIAT) to assess unacknowledged attitudes towards morally charged scenarios. Our results indicate that acute lorazepam administration does not significantly alter moral judgments, including implicit moral attitudes, explicit justice sensitivity, and blame/praise evaluations. Lorazepam-induced changes in moral sensitivity appeared to vary with baseline levels, with individuals exhibiting higher baseline JSI or D scores tending to show greater reductions following administration. These findings support the involvement of GABAergic modulation in moral cognition, albeit without clear behavioral consequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent scientific literature shows that emotions, particularly negative ones like anxiety—as well as neuroticism, a personality trait—significantly influence moral decision-making1. These findings reveal that moral attitudes are deeply intertwined with affective responses alongside logical deliberation2,3.

Negative emotionality and neuroticism affect a person’s likelihood to avoid antisocial behaviors4. Individuals who are prone to risk aversion and are strongly influenced by social pressures tend to have higher levels of neuroticism5,6. This is because the anxiety and negative affect they experience make them more likely to avoid uncertain situations4. Furthermore, conflicts with others—a known trigger for anxiety—further amplify this tendency7,8. The instinctive “gut” reaction many people feel when considering harming another person, even if it might serve a greater good, is now understood as a physical manifestation of emotional negativity and anxiety9.

Moral decision-making is believed to be influenced by mechanisms similar to those used in risk-based decision-making10, as these decisions are often made without knowing their outcomes in advance11. Nevertheless, while the outcomes of deontological judgments, which are more rule-based, are easier to be inferred, those associated with utilitarian choices—decisions that prioritize the greater good independently of the means to get to it—are not, as the psychological burden (e.g., potential regret and guilt) cannot be predicted. This renders utilitarian judgments more akin to decisions made under risk and uncertainty, similar to gambling10,11.

Moreover, research suggests that strategies to regulate emotions or reduce emotional reactivity can lead to a preference for risky and utilitarian decisions by decreasing negative affect3,12. Conversely, increasing negative emotionality, linked to serotonergic activity in the brain, tends to inhibit utilitarian choices1. Theoretical models of decision-making under uncertainty propose that people are more likely to choose risky or utilitarian options when the potential rewards outweigh the anxiety associated with uncertainty, or when they have the cognitive capacity to suppress moral and emotional responses. Enhanced cognitive ability allows for more rational navigation through moral decision-making13,14.

Clinical observations suggest that anxiety significantly influences the likelihood of choosing harmful actions in moral dilemmas. A study, demonstrated how even inducing anxiety in a mild manner, prompted participants to rate morally worse the utilitarian option in both the switch and the footbridge version of the trolley moral dilemma, even in participants that had previously rated the switch version as morally good10. However, it is important to note that these findings are based on correlational data, which do not establish a direct causal link between anxiety and moral decision-making3.

Furthermore, it has been observed that several neurotransmitters and neuropeptides incur in moral decision-making by way of emotional modulation. Two of said neuropeptides are oxytocin and vasopressin, both of which have been implicated in emotional and social responses: anxiety and stress coping in the former; and aggression, empathy, and parental care (among others) in the latter. Moreover, it has been observed that oxytocin and vasopressin modulate and are modulated by the dopaminergic system, such that their influence is bidirectional15. Regarding the role of the dopaminergic system in moral decision-making, some studies show that increased dopamine levels reduce hyperaltruism—the tendency to prioritize others’ suffering over one’s own16; while others found no link between dopaminergic activity and deontological versus utilitarian judgements17. In Parkinson’s disease patients, dopaminergic hypoactivity has been linked to patients within the hyper-honest subgroup (who demonstrate less propensity towards deceptive tendencies than neurotypical controls), while dopaminergic hyperactivity was associated with those in the hypo-honest subgroup (often characterized by comorbidities with impulse control disorders). These patterns appear to reflect dysfunctions in the dopaminergic reward system, influencing the motivation to deceive18. Additionally, research indicates that serotonin upregulation enhances moral judgment by increasing harm aversion19. Taken together, oxytocin, vasopressin, the serotonergic and dopaminergic systems jointly modulate moral cognition and emotional responses to moral stimuli, influencing moral decision-making through distinct effects15,16.

Lorazepam, a high-potency benzodiazepine, is commonly prescribed to relieve anxiety symptoms20. It enhances GABA activity in the brain, a neurotransmitter that inhibits neural activity, through binding to GABA receptors. Research shows that lorazepam increases participants’ willingness to endorse harmful actions in moral dilemmas, whether for selfish or utilitarian reasons3. This suggests that anxiolytic drugs like lorazepam may affect moral decision-making by reducing the emotional negativity associated with anxiety and modulating cognitive processes12,21.

This double-blind, crossover design, placebo-controlled study aims to evaluate how lorazepam influences moral evaluation and attitudes, addressing limitations in previous research. Earlier studies3 relied on questionnaires and other self-reported measures probing explicitly for moral attitudes. Nevertheless, this approach leaves the accuracy of these instruments subject to social desirability biases22; thus, susceptible to the participants’ ability to intentionally alter or mask their genuine responses.

In the current research, explicit measures of moral attitudes, such as the Justice Sensitivity Inventory (JSI), are used. The JSI distinguishes between self-oriented and other-oriented (utilitarian) justice sensitivities and moral attitudes. Additionally, the study incorporates the morality version of the Implicit Association Test (mIAT) to assess individuals’ involuntary attitudes toward morally charged scenarios23,24. The mIAT measures the speed and accuracy with which participants categorize concepts, like associating “moral” versus “immoral” actions with evaluative attributes. Participants are presented with congruent pairs (e.g., moral scenarios paired with positive words, and immoral scenarios paired with negative words) and incongruent pairs (e.g., moral scenarios paired with negative words, and immoral scenarios paired with positive words). Differences in reaction times between these conditions arise because congruent pairs align with automatic cognitive associations, leading to faster responses, while incongruent pairs demand greater cognitive effort, resulting in slower reaction times. Faster and more accurate associations suggest a stronger link between these concepts in memory, while slower associations suggest a weaker connection. By analyzing these reaction time differences, the mIAT provides insight into the automatic cognitive processes underlying moral evaluations, offering a valuable complement to explicit measures, which are often subject to social desirability biases and deliberate self-presentation concerns. This approach allows researchers to explore the subtle and unconscious aspects of moral cognition that inform ethical behavior23.

Our previous studies have demonstrated that implicit moral attitudes, like other implicit attitudes, are inherently unstable and can be modulated by situationally induced changes. Even in the absence of experimental manipulations, the test-retest reliability of the Implicit Association Test (IAT) remains relatively low (r = 0.5–0.6) over time, particularly when compared to conceptually corresponding explicit measures (weighted average r = 0.75) in purely longitudinal assessments25. Similarly, test-retest reliability declined further when modulatory factors were introduced. This instability may be attributed to two key factors: (1) the inherently low test-retest reliability of the IAT and (2) the IAT’s heightened sensitivity to modulatory influences, with effects likely varying across individuals rather than being uniformly distributed. For instance, the modulation of the mIAT is highly dependent on individual characteristics, such as baseline attitudes, even in the absence of external interventions. Social factors—including the presence of others and variations in perceived agency (actor vs. observer)—have been shown to influence both implicit moral attitudes (△D in mIAT) and justice sensitivity (△JSI). These social modulation effects further vary as a function of participants’ baseline characteristics, such as initial D and JSI scores26,27. Considering the role of lorazepam-induced social modulation in moral decision-making and associated neural mechanisms12,28, we hypothesize that acute lorazepam administration will impact implicit moral attitudes and justice sensitivity based on baseline features, such as mIAT and JSI scores, under placebo conditions. This aligns with previous studies26,27, which highlight the interactions between baseline characteristics and social factors, leading to varying levels of influence.

Specifically, building on previous findings demonstrating that lorazepam reduces inhibitions in moral dilemmas, thereby increasing the likelihood of utilitarian choices, this study hypothesizes that lorazepam will influence both explicit and implicit moral attitudes, with a more pronounced effect on implicit attitudes—driven by automatic emotional processes3,12. Particularly, lorazepam is expected to reduce negative emotionality potentially elicited by harm-related scenarios, which may, in turn, diminish the incongruent conflict between positive valence and morally transgressive actions. This effect would lead to reduced D scores (as reflected in changes to D scores rather than overall reaction times on the mIAT), lower other-oriented justice sensitivity, and altered subjective moral evaluations.

Materials and methods

Participants

Eighty-one healthy volunteers (40 men), aged between 21 and 31 years (mean ± SD: 23.556 ± 2.29), participated in the study after providing written informed consent. All participants were Han Chinese and right-handed. They underwent screening for major psychiatric illnesses (e.g., general anxiety disorder) using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) and were excluded if they showed evidence of comorbid neurological disorders (e.g., dementia, seizures), had a history of head injury, or had alcohol or substance abuse or dependence within the past five years. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were not taking any medication at the time of the study. None of the female participants were using oral contraceptives. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of National Yang-Ming University (YM104041E) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

General procedures

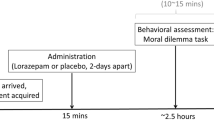

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover design, participants received a single 0.5-mg dose of lorazepam (ATIVAN) on one day, and a single dose of placebo (i.e., vitamin C) on another day. Participants underwent the same experimental procedure for both the placebo and lorazepam administrations, with at least a two-week washout period between sessions. Both lorazepam and placebo were administered orally. The sequence of lorazepam and placebo administration was counterbalanced between participants through a Latin square design, which ensures an equal number of AB (lorazepam-placebo) and BA (placebo-lorazepam) sequences. To align with the pharmacokinetics of lorazepam29, the behavioral assessment took place approximately 2 h after treatment administration. After drug or placebo administration, participants completed the Justice Sensitivity Inventory (JSI) and the subjective evaluation of morally laden scenarios task to assess their explicit moral attitudes, and performed the moral Implicit Association Task (mIAT) to measure their implicit moral attitudes.

Implicit moral attitude (mIAT)

The mIAT was adapted with animations and words as stimuli. The verbal stimuli comprised 26 extremely pleasant and 26 extremely unpleasant words, selected from commonly used Chinese words26,30,31. The animated stimuli included 47 clips depicting everyday dyadic interactions, where each action was characterized as moral or immoral based on outcomes of personal assistance or harm, respectively27,32 (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for an example of the visual stimuli). The mIAT followed the experimental design outlined by Greenwald et al.23, consisting of five discrimination blocks:

-

Block 1, ‘initial target-concept discrimination,’ has participants categorizing clips as moral (right response key) or immoral (left response key).

-

Block 2, ‘attribute discrimination,’ involves categorizing words as negative (right response key) or positive (left response key).

-

Block 3, ‘combined target-concept discrimination,’ presents clips and words in alternating trials, with moral clips paired with negative words (right response key) and immoral clips with positive words (left response key).

-

Block 4, ‘reversed target-concept discrimination,’ reverses the response assignment from Block 1, with moral clips (left response key) and immoral clips (right response key).

-

Block 5, ‘combined reversed target-concept discrimination,’ pairs immoral clips with negative words (right response key) and moral clips with positive words (left response key).

The sequences of the blocks (12345/42513) were counterbalanced to mitigate sequential effects. Half of the participants first encountered the incongruent block, and the other half started with the congruent block. Blocks 1, 2, and 4 consisted of 20 trials each, while Blocks 3 and 5 contained 40 trials each, with words and/or clips randomized within each block. Each trial began with a 1000-ms fixation cross, followed by a stimulus, presented on a computer using E-Prime version 2.0 software (Psychology Software Tools). Participants were instructed to categorize each word or clip as quickly and accurately as possible, with ten practice trials preceding Blocks 3 and 5. Accuracy rates and reaction times (RT) for Blocks 3 and 5 were recorded.

Performance on the mIAT is quantified using D scores, which are calculated by subtracting the mean reaction time (RT) of congruent (moral-negative) blocks from that of incongruent (moral-positive) blocks, and dividing the result by the pooled standard deviation of the two blocks33 As both the numerator and denominator are measured in milliseconds, the resulting D score is a dimensionless (unitless) value. Higher D scores indicate stronger implicit moral attitudes, reflected by longer RTs for incongruent blocks or shorter RTs for congruent blocks.

To account for the sensitivity of reaction time (RT) differentials to outliers and extreme values, RTs exceeding two standard deviations from the participant’s individual mean within each block were excluded as outliers, comprising less than 3% of all responses. This exclusion was performed separately for each discrimination block to address block-specific variability. Additionally, RTs faster than 300 ms or slower than 6000 ms, considered extreme and indicative of inattention, were excluded from analysis, accounting for less than 1% of all responses. The remaining RTs were used to compute differential scores, ensuring consistency and accuracy in the analysis33.

Explicit measure of justice sensitivity: the justice sensitivity inventory (JSI)

The Justice Sensitivity Inventory (JSI) is a self-report psychometric tool designed to assess an individual’s sensitivity to unjust situations34. The inventory encompasses four distinct perspectives—beneficiary, observer, perpetrator, and victim—with each perspective comprising 10 items. Respondents rate these items on a six-point scale ranging from 0 (‘Not at all’) to 5 (‘Exactly’). The resultant scores reflect an individual’s sensitivity to moral norm violations and perceptions of injustice. Scores from the beneficiary, observer, and perpetrator perspectives are often aggregated to form a composite measure of other-oriented sensitivity35. This dimension of justice sensitivity is associated with traits such as high agreeableness, conscientiousness, and empathy. In contrast, a self-oriented justice sensitivity tends to correlate with higher levels of neuroticism and lower levels of agreeableness (see Supplementary Table 1 for an example of the questions).

Subjective evaluations on morally laden scenarios

A set of 45 validated animations from previous fMRI studies, depicting ecologically valid dyadic social interactions, was presented26,27,36. Each animation comprised three images, set to durations of 1000 milliseconds for the first image, 200 milliseconds for the second, and 1000 milliseconds for the third, portraying scenarios of: [1] a person alleviating another’s physical pain (helping), [2] a person inflicting physical harm on another (harming), and [3] baseline stimuli depicting an action irrelevant to another person (neutral). The protagonists’ faces were obscured to prevent any emotional reactions from being visible to participants. The order of scenarios was randomized for each participant. In each animation trial, participants were asked to assess moral reasoning via a computer-based visual analogue scale. They rated each scenario on a Likert scale from “very much blameworthy (− 7)”, through “neutral (0)”, to “very much praiseworthy (7) [see Supplementary Fig. 2 for an example of the visual stimuli].

Results

Implicit moral attitude (mIAT) results

In this cohort, the D scores ranged from − 1.29 to 1.69, with mean and standard deviation of 0.68 ± 0.43 in the placebo condition, and from − 0.19 to 1.36, with mean and standard deviation of 0.63 ± 0.35 in the lorazepam condition (Table 1). While acute lorazepam administration did not significantly affect overall D scores [t(80) = 0.779, p = 0.438], we conducted a univariate ANCOVA to examine whether lorazepam-induced changes in implicit moral attitudes (△D, defined as lorazepam D minus placebo D) were associated with gender and baseline D. The model included △D as the dependent variable [F(3, 77) = 31.67, p < 0.001, partial eta squared (pη²) = 0.55], with gender as the fixed independent factor and baseline D (i.e., placebo D) and order of administration as covariates. The results revealed that baseline D significantly predicted △D [F(1, 77) = 94.8, p < 0.001, pη² = 0.55], whereas neither gender (p = 0.916) nor order of administration (p = 0.976) had a significant effect on △D (see Fig. 1). (Fig. 1).

Justice sensitivity (JSI) results

In this cohort, total JSI scores ranged from 8.8 to 26.4 with a mean and standard deviation of 17.21 ± 3.19 in the placebo condition, whereas in the lorazepam condition, scores ranged from 8.5 to 26.8 with a mean and standard deviation of 17.53 ± 3.07. For the self-oriented Justice Sensitivity Index (JSI), while acute lorazepam administration did not significantly affect overall self-oriented JSI scores [t(80) = -0.272, p = 0.787], a univariate ANCOVA was conducted to examine factors influencing lorazepam-induced changes. The model included △JSI-self (defined as lorazepam JSI-self minus placebo JSI-self) as the dependent variable [F(3, 77) = 3.869, p = 0.012, partial eta squared (pη²) = 0.131], with gender as the fixed independent factor, and baseline JSI-self (i.e., placebo JSI-self) and order of administration as covariates. Results indicated that baseline JSI-self significantly predicted △JSI-self [F(1, 77) = 10.376, p = 0.002, pη² = 0.119] (Fig. 2A), whereas neither gender (p = 0.604) nor order of administration (p = 0.768) had a significant effect on △JSI-self.

Lorazepam effects on justice sensitivity (JSI) as a function of baseline scores. (A) Baseline JSI-self scores in the placebo condition were significantly correlated with △JSI-self (r = − 0.36, p = 0.001). (B) Baseline JSI-other scores in the placebo condition were significantly correlated with △JSI-other (r = − 0.33, p = 0.003).

For the other-oriented Justice Sensitivity Index (JSI), acute lorazepam administration showed a trend toward reducing overall other-oriented JSI scores, although this effect did not reach statistical significance [t(80) = -1.943, p = 0.056]. To further investigate potential modulators of lorazepam-induced changes, a univariate ANCOVA was conducted with △JSI-other (defined as lorazepam JSI-other minus placebo JSI-other) as the dependent variable [F(3, 77) = 3.492, p = 0.020, partial eta squared (pη²) = 0.12]. Gender was included as the fixed independent factor, and baseline JSI-other (i.e., placebo JSI-other) and order of administration were included as covariates. The analysis revealed that baseline JSI-other significantly predicted △JSI-other [F(1, 77) = 8.78, p = 0.004, pη² = 0.102] (Fig. 2B), whereas neither gender (p = 0.363) nor order of administration (p = 0.754) had a significant effect on △JSI-other.

Subjective moral evaluations

The 2 (DRUG: placebo vs. lorazepam; a within-subject factor) x 2 (GENDER: male vs. female; a between-subject factor) x 2 (SCENARIO: harming vs. neutral vs. helping; a within-subject factor) mixed ANOVA on subjective moral evaluations showed a main effect of scenario (F(2, 158) = 1324.759, p < 0.001, pη2) = 0.944; Harming vs. Neutral vs. Helping: -5.103 ± 0.12 vs. 1.208 ± 0.096 vs. 4.502 ± 0.135, mean ± standard error), while the main effects of drug (F(1, 79) = 0.656, p = 0.42, pη2 = 0.008) and gender (F(1, 79) = 2.951, p = 0.09, pη2 = 0.036) did not reach significance, nor did any interactions with drug or gender (all p > 0.2). The harming scenario was rated significantly more blameworthy than the neutral scenario (-5.103 ± 0.12 vs. 1.208 ± 0.096, p < 0.001), while the helping scenario was evaluated as significantly more praiseworthy compared to the neutral scenario (4.502 ± 0.135 vs. 1.208 ± 0.096, p < 0.001).

Implicit moral attitude (mIAT), justice sensitivity (JSI), and subjective moral evaluations

Parallel to previous findings26,32, participants who scored higher on the other-oriented Justice Sensitivity Inventory (JSI) assigned significantly more praise for helping (in the placebo condition: r = 0.321, P = 0.003; in the lorazepam condition: r = 0.355, P = 0.001) as well as more blame for harming (in the placebo condition: r = -0.355, P = 0.001; in the lorazepam condition: r = -0.312, P = 0.005), regardless of being in the placebo or lorazepam condition. However, neither blame nor praise ratings were associated with self-oriented JSI scores in either the placebo (blame: r = -0.141, P = 0.21; praise: r = 0.211, P = 0.059) or lorazepam condition (blame: r = -0.182, P = 0.104; praise: r = 0.187, P = 0.095). The relationship between justice sensitivity and moral evaluation was influenced by gender, with only men showing a significant association between other-oriented JSI and praise (in the placebo condition: r = 0.461, P = 0.002; in the lorazepam condition: r = 0.463, P = 0.002), and between other-oriented JSI and blame (in the placebo condition: r = -0.536, P < 0.001; in the lorazepam condition: r = -0.524, P < 0.001). In contrast, women did not demonstrate this pattern of association between justice sensitivity and moral evaluation (all P > 0.2). Fisher’s r-to-z transformation tests further confirmed the moderating effect of gender on the relationship between justice sensitivity and moral evaluation (Δz = 1.91, P = 0.028, one-tailed) (Fig. 3A). Implicit moral attitude (measured by the mIAT) did not significantly predict moral evaluation in any condition (i.e., placebo/lorazepam, male/female, and harming/helping) (all P > 0.2).

(A) The association between justice sensitivity and moral evaluation was modulated by the gender factor. While men showed a significant association between other-oriented JSI and blameworthy ratings for harming actions in lorazepam condition (r = -0.524, P < 0.001), women did not show this pattern of correlation (r = -0.14, P = 0.39). Fisher r-to-z transformation tests further corroborated the modulating role of gender on the justice sensitivity-moral evaluation relationship (△z = 1.91, P = 0.028, one-tailed). (B) The reliability of test-retest association between placebo and lorazepam condition was modulated by the implicit versus explicit measure of moral attitudes. While JSI showed a strong correlation between placebo and lorazepam condition (r = 0.872, P < 0.001), mIAT did not show this pattern (r = 0.135, P = 0.231). Fisher r-to-z transformation tests further corroborated the modulating role of implicit versus explicit moral attitudes on the placebo-lorazepam test-retest relationship (△z = 7.51, P < 0.001).

Regarding the effect of lorazepam on implicit moral attitude (mIAT) and justice sensitivity (JSI), while the total JSI score demonstrated a strong test-retest reliability between conditions (placebo and lorazepam) with a correlation of r = 0.872 (P < 0.001), the mIAT did not exhibit a similar pattern of correlation between the placebo and lorazepam conditions (r = 0.135, P = 0.231). Fisher’s r-to-z transformation tests further confirmed the distinct roles of implicit (mIAT) versus explicit (JSI) moral attitudes in influencing the test-retest relationship between the placebo and lorazepam conditions (Δz = 7.51, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3B). This finding aligns with previous ANOVA results, indicating that lorazepam had an overall effect in individuals with both low and high JSI scores (Fig. 2B), whereas its impact was only observed in participants with high baseline mIAT D scores. This differential effect of lorazepam on explicit and implicit moral attitudes was not influenced by the gender factor, as indicated by the correlation scores in female (JSI: r = 0.81, P < 0.001; mIAT: r = 0.098, P = 0.546) and male participants (JSI: r = 0.904, P < 0.001; mIAT: r = 0.202, P = 0.206).

Discussion

This research, a double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled study, explored the effects of lorazepam on moral judgment and attitudes, with a particular focus on the modulation of GABAergic potential. The research aimed to differentiate between self-interested and utilitarian behaviors using the Justice Sensitivity Inventory (JSI; self-oriented vs. other-oriented justice), and examined moral attitudes through both implicit and explicit measures. The key finding was that acute lorazepam administration did not significantly affect moral judgments overall, though changes in moral sensitivity appeared to vary with baseline levels, with greater reductions observed among individuals with higher baseline JSI and D scores. Specifically, participants with higher baseline values on the Implicit Association Test (mIAT) showed greater declines in D scores following lorazepam administration. A similar pattern was observed for both self- and other-oriented justice sensitivity, with participants exhibiting higher baseline JSI scores showing greater decreases as measured by the Justice Sensitivity Inventory. Furthermore, harmful scenarios were judged as more blameworthy and helping scenarios as more praiseworthy than neutral scenarios, though these judgments were unaffected by lorazepam administration.

One critical aspect of this study was the need to distinguish the effects of lorazepam on moral processing from its potential sedative side effects, given its known impact on psychomotor performance and reaction times (RTs)37,38,39. Therefore, RTs were used as an objective measure of sedation. If the acute administration of lorazepam did not specifically affect moral processing, it would be expected to evenly slow down RTs in both congruent and incongruent pairs of the mIAT, resulting in no effect on D scores. However, the study found that lorazepam’s effects varied depending on moral valence, suggesting that the observed changes were not solely due to sedation, and that lorazepam does specifically interact with moral processing mechanisms.

Although acute lorazepam administration did not significantly affect moral judgments in general, participants with higher baseline values on the mIAT exhibited greater declines in D scores following lorazepam administration. Higher D scores are associated with longer reaction times, indicating that individuals with lower D scores are quicker in their responses and possibly more attuned to their moral intuitions. Therefore, our findings appear to contradict earlier research, including the study by Martinez, et al.31, which suggested that individuals with lower D scores—often linked to those possessing the S allele in the 5-HTTLPR serotonin transporter polymorphism—relied more heavily on moral intuitions. Nevertheless, it is in line with studies showing that those with LL genotypes of the 5-HTT polymorphism—which tend to have less bioavailability of the neuromodulator serotonin in the synaptic cleft—reported less difficulty making harmful decisions, as they tend to incur in fewer negative emotions40. Research indicates that the upregulation of serotonin reinforces moral judgement by increasing aversion to harm19. Furthermore, while depletion of tryptophan—a serotonin precursor—elevates guilt in highly empathic individuals, it increases annoyance in those with high psychopathy traits. These findings suggest that serotonin fluctuation interacts with personality differences to produce diverse emotional responses41. The discrepancy may be further attributed to the different neurochemical systems involved—while 5-HTTLPR is related to the serotonergic system, lorazepam acts within the GABAergic system. Lorazepam might reduce anxiety-induced discomfort through the GABAergic system while preserving certain benefits like hypervigilance via the serotonergic system. However, previous studies have shown that serotonin transporters and GABAergic receptors are both linked to neuroticism42, with the former significantly affecting amygdala activity, a brain region where lorazepam is also known to exert significant inhibitory effects43,44,45. Despite this, the complex interplay between the GABAergic and serotonergic systems has not been definitively established46,47.

Notwithstanding, our findings concerning the interaction between mIAT D scores and lorazepam administration should be approached with caution. The test-retest reliability of the IAT ranges from r = 0.5 to 0.625; however, in our study, the correlation of D scores between the placebo and lorazepam sessions was notably lower, at r = 0.135. Previous research indicates that implicit measures typically have lower stability over time compared to explicit measures across various domains (including self-concept, racial and political attitudes, among others), as they are more sensitive to contextual and situational influences, including social factors such as the presence of others or varying perspectives regarding agency25,26,27. Therefore, we contend that the low test-retest reliability observed in our mIAT findings may be indicative of the dynamic nature of implicit attitudes rather than a lack of reliability. This is particularly relevant following the administration of lorazepam, an anxiolytic drug observed to induce moral flexibility at the implicit level3,12,28. Additionally, lorazepam may affect different moral decision-making styles (e.g., deontological versus utilitarian), which are known to be context-dependent3; and potentially explaining its impact primarily on higher mIAT D scorers, which previous studies have associated with utilitarian moral decision-making31. Thus, these findings could be ascribed to certain selective effects of lorazepam. Nevertheless, and as previously stated, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

Regarding explicit justice sensitivity, lorazepam did not significantly alter moral sensitivity for either self- or other-oriented justice. However, these changes were significantly modulated by baseline levels of justice sensitivity. Participants with higher baseline scores tended to show greater declines in justice sensitivity following lorazepam administration. This trend toward reduced sensitivity to perceived injustice aligns with expectations, given lorazepam’s stress-, anxiety-, and sensitivity-reducing properties, as well as the explicit nature of the JSI, which captures consciously controlled moral cognition34,48. Although harm scenarios were consistently judged as more blameworthy and help scenarios as more praiseworthy than neutral ones—regardless of drug condition—the extent of sensitivity reduction may vary depending on individuals’ baseline levels. Additionally, the moral evaluations predicted by justice sensitivity—found to be greater in men than in women—may be partly attributed to socially desirable response tendencies, which can influence self-reported justice sensitivity and moral evaluations. Previous research has noted lower sensitivity to consequences among women49,50. While women consistently report more ethical responses than men, they are also more likely to respond in a socially desirable manner51. Thus, social desirability bias may significantly contribute to the observed relationship between gender and ethical decision-making51.

Our study found no interaction between Lorazepam administration, and D and JSI scores based on gender. Previous research has shown that in men and free-cycling women (i.e., not using oral contraceptives), LL homozygotes of the 5-HTTLPR serotonin transporter polymorphism exhibit reduced deontological tendencies compared to S allele carriers. In contrast, women on oral contraceptives with LL genotypes tend to make more deontological choices40. In this same line of research, intranasal administrations of oxytocin exhibited a differential effect based on gender. In male participants, intranasal oxytocin increased neural activity in disgust-related and self-processing regions, leading to more self-beneficial decisions in moral dilemmas, and contrary to oxytocin’s typical prosocial effects. In women, intranasal oxytocin enhanced self-processing activity but did not affect disgust responses. Women also showed a preference for other-directed rather than self-benefitting choices in moral dilemmas, aligning with prosocial behaviors15. It has been hypothesized that said selfish behavior in male participants could be due to oxytocin promoting in-group protection, where selfishness increases the survival chances of the in-group. This explanation would align with prior findings on oxytocin’s role in fostering in-group favoritism52. This is just to show that there is a complex interaction between gender, hormonal and endocrine systems, neuromodulator activity, and moral decision-making, such that it makes it challenging for our study to tease out these gender-based differences with the limited scope of our research.

Some limitations for this study should be acknowledged, particularly regarding the influence of individual differences and potential response biases in explicit moral judgments. Explicit measures can be affected by participants’ desire to please the experimenter or avoid endorsing socially undesirable behaviors. Cognitive load and the capacity to imagine different moral outcomes also play a role in shaping these judgments53. Therefore, post-session questionnaires assessing participants’ perceptions towards the experimenter could be useful for evaluating the influence of response expectancy in drug-placebo studies54. Secondly, we recognize that the test-retest reliability of the mIAT during lorazepam administration was low in our study. This finding aligns with the variability documented in previous research on implicit measures, which are known to be affected by contextual and situational factors55. However, we believe that further research is necessary to refine the methodology and evaluate its reliability under conditions specifically designed for this purpose. Last but not least, future research could benefit from including endophenotypic measures such as EEG or fMRI to better understand the mechanisms underlying lorazepam’s effects on moral cognition56.

In conclusion, this study reinforces previous findings that lorazepam, a GABA receptor agonist, may influence the underlying mechanisms of moral decision-making and moral cognition3, although without clear behavioral consequences. These findings offer a solid foundation for further investigations into the interactions between neuromodulatory drugs and moral cognition, paving the way for a deeper understanding of how pharmacological agents alongside their target neurotransmitters and neuropeptides impact ethical decision-making and social behavior.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Lucas, B. J. & Galinsky, A. D. Is utilitarianism risky?? How the same antecedents and mechanism produce both utilitarian and risky? choices. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10, 541–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615583130 (2015).

Chen, C., Martinez, R. M., Chen, Y. C., Fan, Y. T. & Cheng, Y. The neural mediators of moral attitudes and behaviors. Behav. Brain Res. 430, 113934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2022.113934 (2022).

Perkins, A. M. et al. A dose of ruthlessness: interpersonal moral judgment is hardened by the anti-anxiety drug lorazepam. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 142, 612–620. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030256 (2013).

Zeigler-Hill, V., Southard, A. C., Archer, L. M. & Donohoe, P. L. Neuroticism and negative affect influence the reluctance to engage in destructive obedience in the milgram paradigm. J. Soc. Psychol. 153, 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2012.713041 (2013).

Drake, K. E. Interrogative suggestibility: life adversity, neuroticism, and compliance. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 48, 493–498 (2010).

Maner, J. K. et al. Dispositional anxiety and risk-avoidant decision-making. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 42, 665–675 (2007).

Grupe, D. W. & Nitschke, J. B. Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: an integrated Neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 488–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3524 (2013).

Steimer, T. The biology of fear- and anxiety-related behaviors. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 4, 231–249 (2002).

Greene, J. D., Nystrom, L. E., Engell, A. D., Darley, J. M. & Cohen, J. D. The neural bases of cognitive conflict and control in moral judgment. Neuron 44, 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.027 (2004).

Zhao, J., Harris, M. & Vigo, R. Anxiety and moral judgment: the shared deontological tendency of the behavioral Inhibition system and the unique utilitarian tendency of trait anxiety. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 95, 29–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.024 (2016).

Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. Choices, values, and frames. Am. Psychol. 39, 341–350. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.39.4.341 (1984).

Martinez, R. M. et al. Negative emotionality downregulation affects moral choice but not moral judgement of harm: a Pharmacological study. Sci. Rep. 14, 1200. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51345-8 (2024).

Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nystrom, L. E., Darley, J. M. & Cohen, J. D. An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science 293, 2105–2108. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1062872 (2001).

Loewenstein, G. F., Weber, E. U., Hsee, C. K. & Welch, N. Risk as feelings. Psychol. Bull. 127, 267–286 (2001).

Reese, M., Bryant, D. & Ethridge, L. Biomarkers for moral cognition: current status and future prospects for neurotransmitters and neuropeptides. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 113, 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.03.009 (2020).

Crockett, M. J. et al. Dissociable effects of serotonin and dopamine on the valuation of harm in moral decision making. Curr. Biol. 25, 1852–1859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.05.021 (2015).

Mueller, D. & Halfmann, K. Dopamine, religiosity, and utilitarian moral judgment. Soc. Neurosci. 16, 627–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2021.1974935 (2021).

Ponsi, G., Scattolin, M., Villa, R. & Aglioti, S. M. Human moral decision-making through the lens of Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 7, 18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-021-00167-w (2021).

Crockett, M. J., Clark, L., Hauser, M. D. & Robbins, T. W. Serotonin selectively influences moral judgment and behavior through effects on harm aversion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 107, 17433–17438. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1009396107 (2010).

Gould, R. A., Otto, M. W., Pollack, M. H. & Yap, L. Cognitive behavioral and Pharmacological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary meta-analysis. Behav. Ther. 28, 285–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(97)80048-2 (1997).

Richter, A., Grimm, S. & Northoff, G. Lorazepam modulates orbitofrontal signal changes during emotional processing in catatonia. Hum. Psychopharmacology: Clin. Experimental. 25, 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.1084 (2010).

Randall, D. M. & Fernandes, M. F. in Citation classics from the Journal of Business Ethics: Celebrating the first thirty years of publication. Advances in business ethics research. 173–190 (Springer Science + Business Media, (2013).

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E. & Schwartz, J. L. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 1464–1480 (1998).

Luo, Q. et al. The neural basis of implicit moral attitude–an IAT study using event-related fMRI. Neuroimage 30, 1449–1457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.005 (2006).

Gawronski, B., Morrison, M., Phills, C. E., Galdi, S. J. P. & Bulletin, S. P. Temporal stability of implicit and explicit measures: A longitudinal analysis. 43, 300–312 (2017).

Chen, C., Martinez, R. M., Chen, Y. & Cheng, Y. Pointing fingers at others: the neural correlates of actor-observer asymmetry in blame attribution. Neuropsychologia 136, 107281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2019.107281 (2020).

Chen, C., Martinez, R. M. & Cheng, Y. The key to group fitness: the presence of another synchronizes moral attitudes and neural responses during moral decision-making. Neuroimage 213, 116732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116732 (2020).

Chen, C., Martinez, R. M., Chen, Y. C., Fan, Y. T. & Cheng, Y. The anti-anxiety drug lorazepam changes implicit behaviors but not explicit evaluations of sense of agency under authoritative pressure: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Front. Psychol. 13, 991357. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.991357 (2022).

Kyriakopoulos, A. A. & Greenblatt, D. J. Shader, R. I. Clinical pharmacokinetics of Lorazepam: a review. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 39, 16–23 (1978).

Chen, H. C., Li, W. C., Chou, T. A. & Cho, S. L. Measuring the self-exposure of Chinese people using the implicit association test. Psychol. Test. 49, 217–234 (2002).

Martinez, R. M. et al. The multifaceted effects of serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) on anxiety, implicit moral attitudes, and harmful behaviors. Front. Psychol. 11, 1521. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01521 (2020).

Yoder, K. J. & Decety, J. The good, the bad, and the just: justice sensitivity predicts neural response during moral evaluation of actions performed by others. J. Neurosci. 34, 4161–4166. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4648-13.2014 (2014).

Nosek, B. A., Bar-Anan, Y., Sriram, N., Axt, J. & Greenwald, A. G. Understanding and using the brief implicit association test: recommended scoring procedures. PLoS One. 9, e110938. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110938 (2014).

Schmitt, M., Baumert, A., Gollwitzer, M. & Maes, J. The justice sensitivity inventory: factorial validity, location in the personality facet space, demorgraphic pattern, and normative data. Soc. Justice Res. 23, 211–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-010-0115-2 (2010).

Edele, A., Dziobek, I. & Keller, M. Explaining altruistic sharing in the dictator game: the role of affective empathy, cognitive empathy, and justice sensitivity. Learn. Individual Differences. 24, 96–102 (2013).

Cheng, Y., Chou, J., Martinez, R. M., Fan, Y. T. & Chen, C. Psychopathic traits mediate guilt-related anterior midcingulate activity under authority pressure. Sci. Rep. 11, 14856. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94372-5 (2021).

Smiley, A. Effects of minor tranquilizers and antidepressants on psychomotor performance. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 48 Suppl, 22–28 (1987).

Van Ruitenbeek, P., Vermeeren, A. & Riedel, W. J. Memory in humans is unaffected by central H1-antagonism, while objectively and subjectively measured sedation is increased. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 20, 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.12.003 (2010).

Curran, H. V., Pooviboonsuk, P., Dalton, J. A. & Lader, M. H. Differentiating the effects of centrally acting drugs on arousal and memory: an event-related potential study of scopolamine, lorazepam and diphenhydramine. Psychopharmacol. (Berl). 135, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002130050482 (1998).

Armbruster, D., Lesch, K. P. & Strobel, A. The long and the short of it: 5-HTTLPR and moral judgement. Behav. Brain Res. 452, 114524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2023.114524 (2023).

Kanen, J. W. et al. Serotonin depletion amplifies distinct human social emotions as a function of individual differences in personality. Transl Psychiatry. 11, 81. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-00880-9 (2021).

Sen, S. et al. Serotonin transporter and GABAA alpha 6 receptor variants are associated with neuroticism. Biol. Psychiatry. 55, 244–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.08.006 (2004).

Kreuder, A. K. et al. Common and dissociable effects of Oxytocin and lorazepam on the neurocircuitry of fear. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 117, 11781–11787. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1920147117 (2020).

Paulus, M. P., Feinstein, J. S., Castillo, G., Simmons, A. N. & Stein, M. B. Dose-dependent decrease of activation in bilateral amygdala and Insula by lorazepam during emotion processing. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 62, 282–288. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.282 (2005).

Schunck, T. et al. Effects of lorazepam on brain activity pattern during an anxiety symptom provocation challenge. J. Psychopharmacol. 24, 701–708. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881109104864 (2010).

Olivier, J. D., Vinkers, C. H. & Olivier, B. The role of the serotonergic and GABA system in translational approaches in drug discovery for anxiety disorders. Front. Pharmacol. 4, 74. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2013.00074 (2013).

Ellerbrock, I. et al. Serotonergic gene-to-gene interaction is associated with mood and GABA concentrations but not with pain-related cerebral processing in fibromyalgia subjects and healthy controls. Mol. Brain. 14, 81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13041-021-00789-4 (2021).

Greenwald, A. G. & Banaji, M. R. Implicit social cognition: attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychol. Rev. 102, 4–27 (1995).

Qian, Y., Takimoto, Y., Wang, L. & Yasumura, A. J. C. P. Exploring cultural and gender differences in moral judgment: A cross-cultural study based on the CNI model. 43, 5243–5253 (2024).

Atari, M., Lai, M. H. & Dehghani, M. J. P. o. t. R. S. B. Sex differences in moral judgements across 67 countries. 287, 20201201 (2020).

Dalton, D. & Ortegren, M. J. J. o. B. E. Gender differences in ethics research: The importance of controlling for the social desirability response bias. 103, 73–93 (2011).

Scheele, D. et al. Opposing effects of Oxytocin on moral judgment in males and females. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35, 6067–6076. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22605 (2014).

Gaesser, B., Keeler, K. & Young, L. Moral imagination: facilitating prosocial decision-making through scene imagery and theory of Mind. Cognition 171, 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2017.11.004 (2018).

Gaab, J., Kossowsky, J., Ehlert, U. & Locher, C. Effects and components of placebos with a psychological treatment Rationale - Three Randomized-Controlled studies. Sci. Rep. 9, 1421. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37945-1 (2019).

Gawronski, B., Morrison, M., Phills, C. E. & Galdi, S. Temporal stability of implicit and explicit measures: A longitudinal analysis. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 43, 300–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216684131 (2017).

Canli, T. & Lesch, K. P. Long story short: the serotonin transporter in emotion regulation and social cognition. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 1103–1109. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1964 (2007).

Funding

This work was financially supported by grants from Wan-Fang Hospital, Taipei Medical University (112TMU-WFH-15); the National Science and Technology Council (113-2410-H-038-034 -; 113-2423-H-006 -001 -; 113-2410-H-028 -005 -; 113-2410-H-A49-065-); National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University Hospital (RD2025-002); and the Higher Education Sprout Project (DP2-TMU-114-N-05; TMU-114-N-05) by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.M.M., L.W., Y.C. and C.C. conceived and conceptualized the study. Y.T.F., Y.C.C., K.K.G., Y.N.L. and C.T.Y. collected, managed and analyzed the data. R.M.M., L.W., Y.C. and C.C. conducted the necessary literature reviews and drafted the first manuscript. All authors contributed towards the writing and revision of the final draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

A written informed consent was obtained from all the participants, as well as were given a monetary compensation at the end of the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martinez, R.M., Wei, L., Fan, YT. et al. Acute lorazepam administration does not significantly affect moral attitudes or judgments. Sci Rep 15, 16108 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01109-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01109-9